20.1 Best times for different strokes

The website of the International Swimming Federation (FINA (2021)) publishes results of competitions and datasets containing swimmers’ best times for different strokes and distances. Spearing et al. (2021) used some of this data to compare the performances of swimmers over time and across events using a model based on extreme value theory. They also assessed which world records were most likely to be broken next. As the data are best times for individual swimmers, each swimmer can only appear once in the list for an event. The data used here include the 200 best times for men and women over each of 17 events for individuals, with fewer best times for three relay events. All times are in seconds and have been rounded to two decimal places. Only races in 50 metre pools (long course metres or LCM events) are considered here.

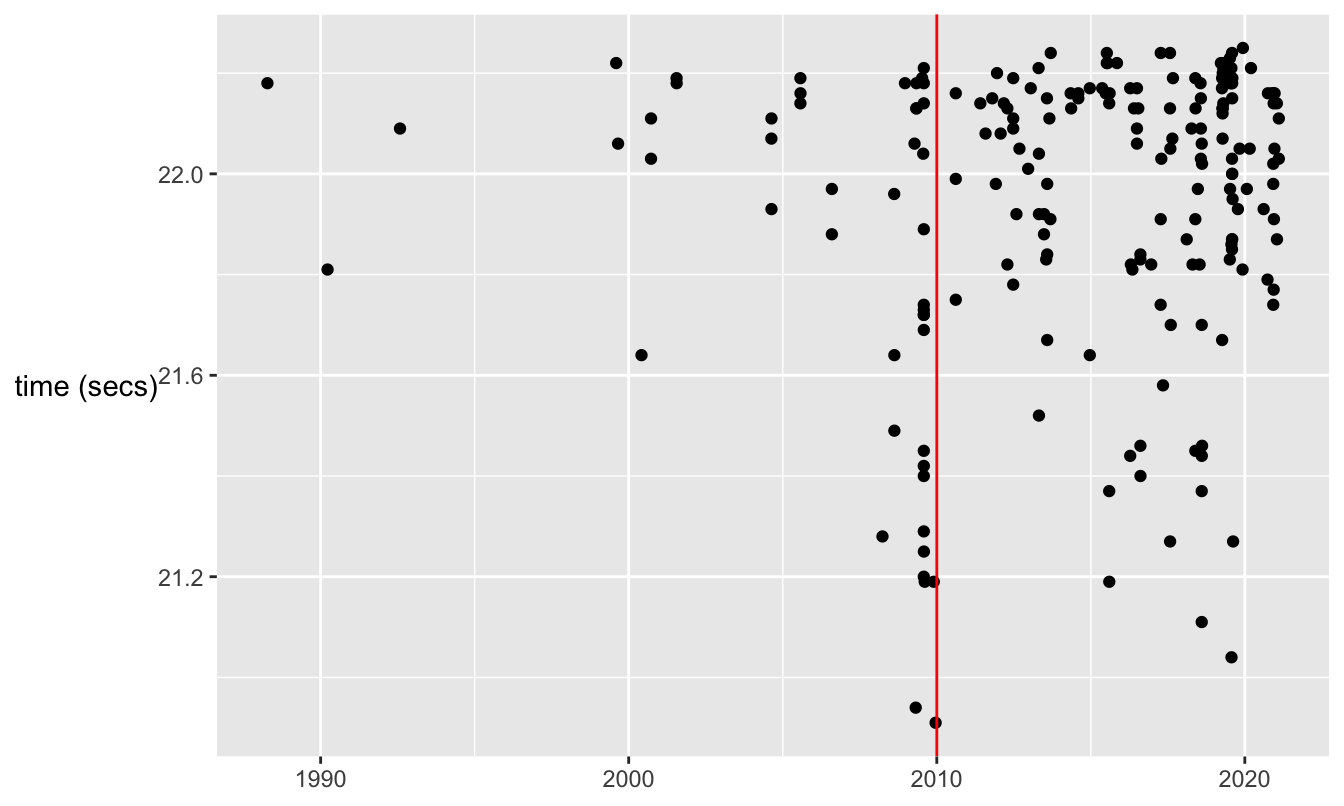

Figure 20.1 is a display of best times by date for an event, in this case the 50 m freestyle for men. Most of the best times have been achieved recently, partly because training methods have improved, partly because there are more swimmers, and partly because more competitions are included on the FINA website. There are a few impressive older performances. It looks like there is an upper limit of just over 22.2 seconds and this must have been the 200th best performance. The very best times were achieved after the introduction of full body swimsuits in 2008 that were permitted at the Beijing Olympics. The suits were banned from 1st January 2010 (marked by a red vertical line).

Figure 20.1: Best times by male swimmers for the 50 m freestyle

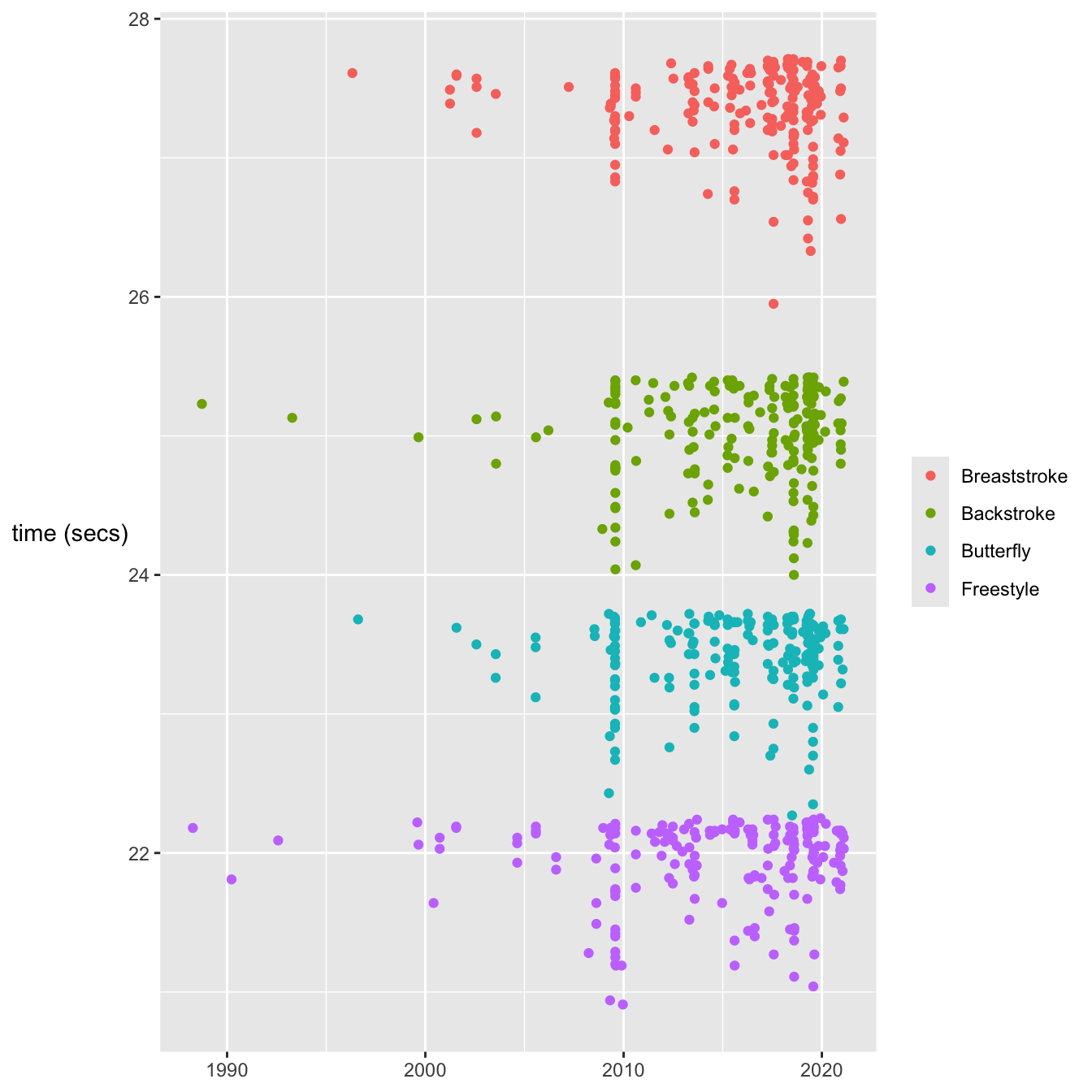

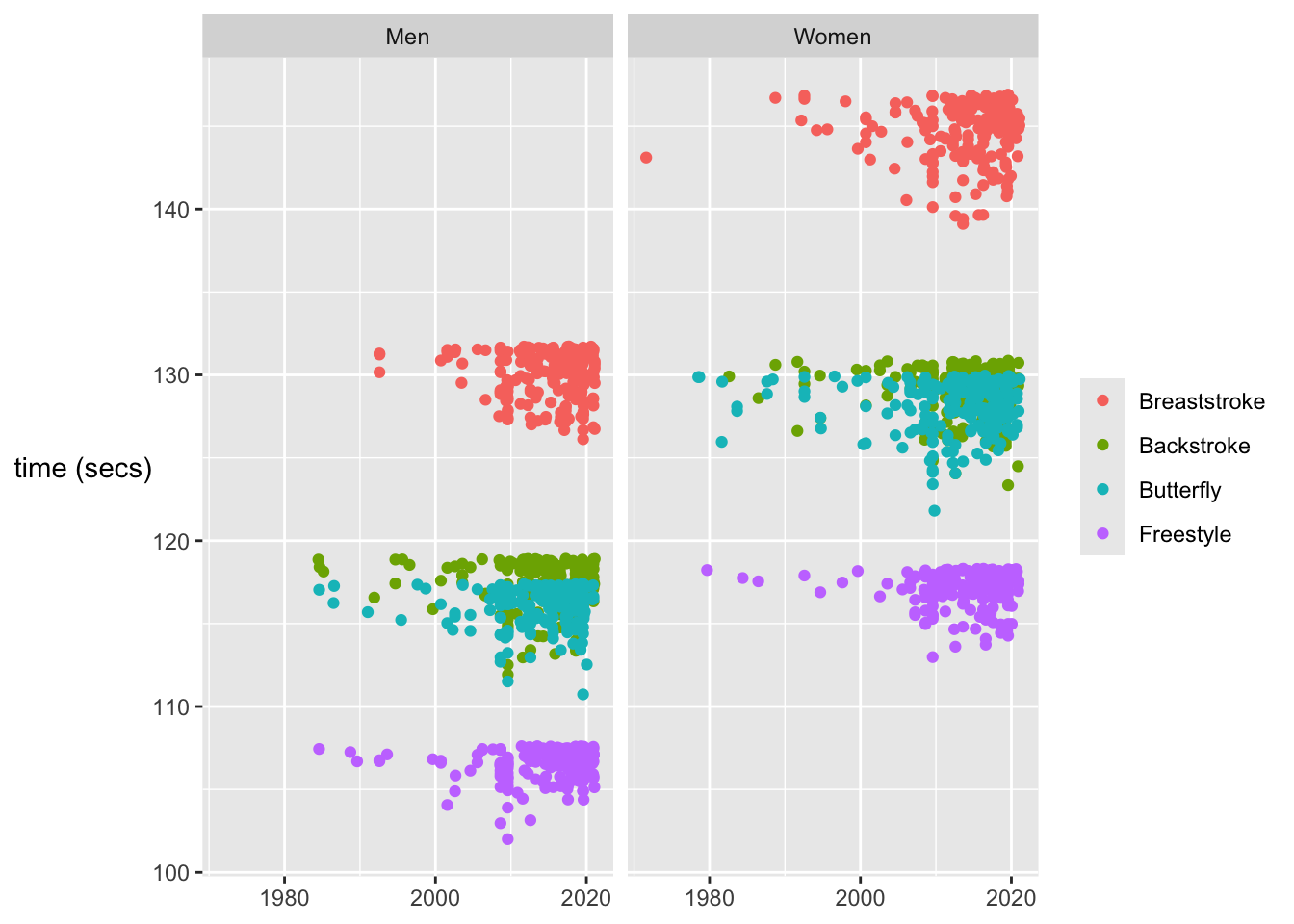

There are four different events over 50 m: freestyle, breaststroke, butterfly, and backstroke. Plotting the sets of 200 best times for men all in the same display presents a striking picture (Figure 20.2).

Figure 20.2: Best times by male swimmers for the four 50 m events

The times for the events are almost completely separated. There is a possible overlap between the fastest butterfly time and the slowest freestyle times. In fact the best time for the butterfly was 22.27 seconds and the two-hundredth best time for the freestyle was 22.25 seconds. Three of the four plots have the same patterns seen in Figure 20.1, a few fine older performances, a string of best times with full body swimsuits in 2009, and a gradual improvement over the past 10 years from the slower times recorded in 2010. There are two exceptions. One is the 50 m backstroke time of Camille Lacourt in 2010. The other is the extraordinary time of Adam Peaty in the 50 m breaststroke in 2017. Unlike in the other events, several breaststroke swimmers have beaten the best full body swimsuit time. Was it of less benefit to breaststroke swimmers?

The ordering of the events is hardly surprising to swimmers. Backstroke swimmers start in the water, while swimmers in the other three events have the advantage of diving in and swimming briefly underwater at the start. The butterfly is a relatively new stroke in official terms. It was introduced before the Second World War and was later used by swimmers in breaststroke competitions. In the early 1950s the best breaststroke times were swum by butterfly swimmers and the butterfly was declared a separate stroke in 1953 (Oppenheim (1970)). This is why the breaststroke world record times increased then, as afterwards breaststroke swimmers had to actually swim breaststroke!

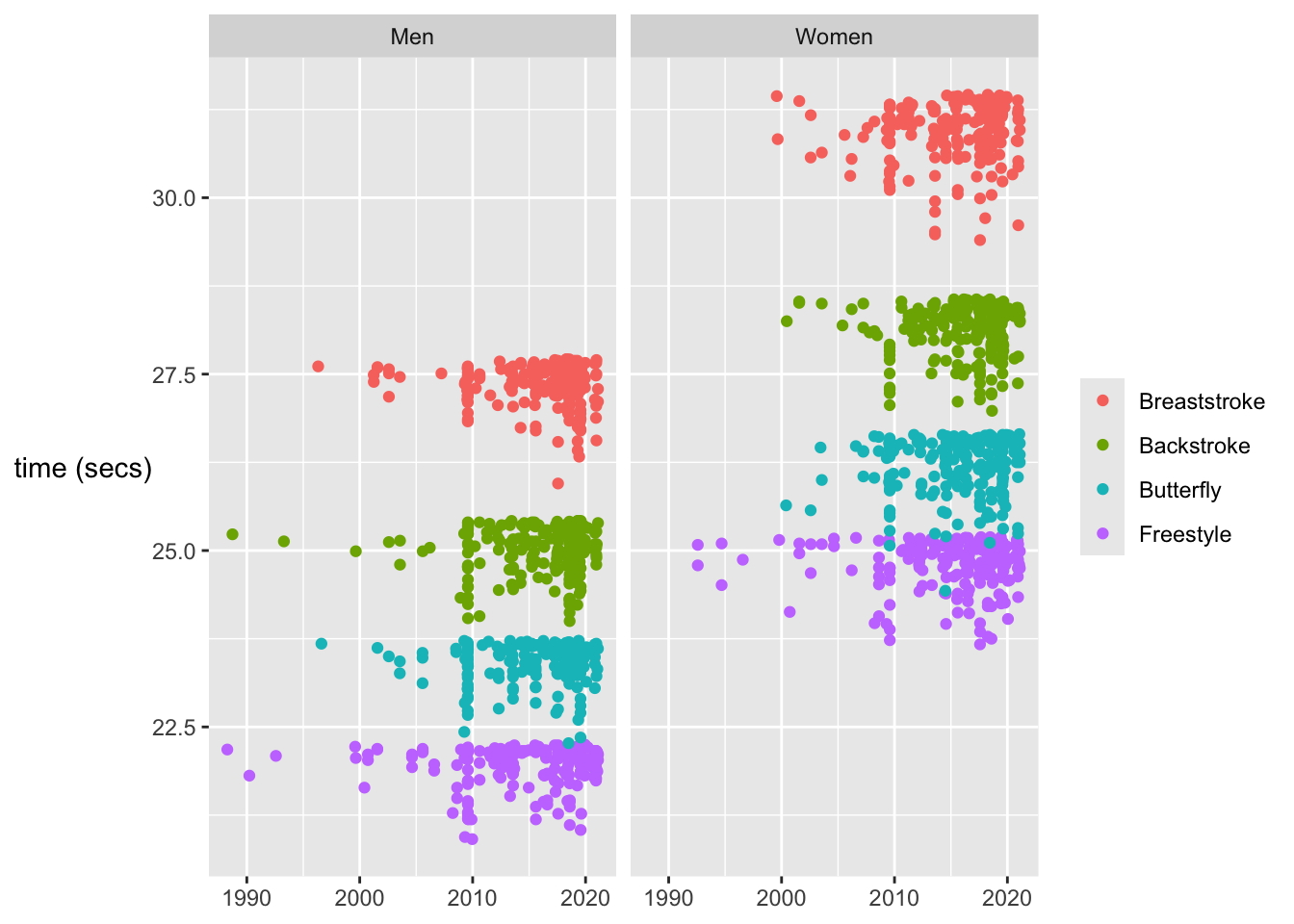

The same patterns hold for the women for the 50 m events with one notable exception. Figure 20.3 shows that the women are in general slower than the men (although the best women swimming freestyle would beat the best male breaststroke swimmers and probably the best male backstroke swimmers too).

Figure 20.3: Best times for the four 50 m events achieved by men and women

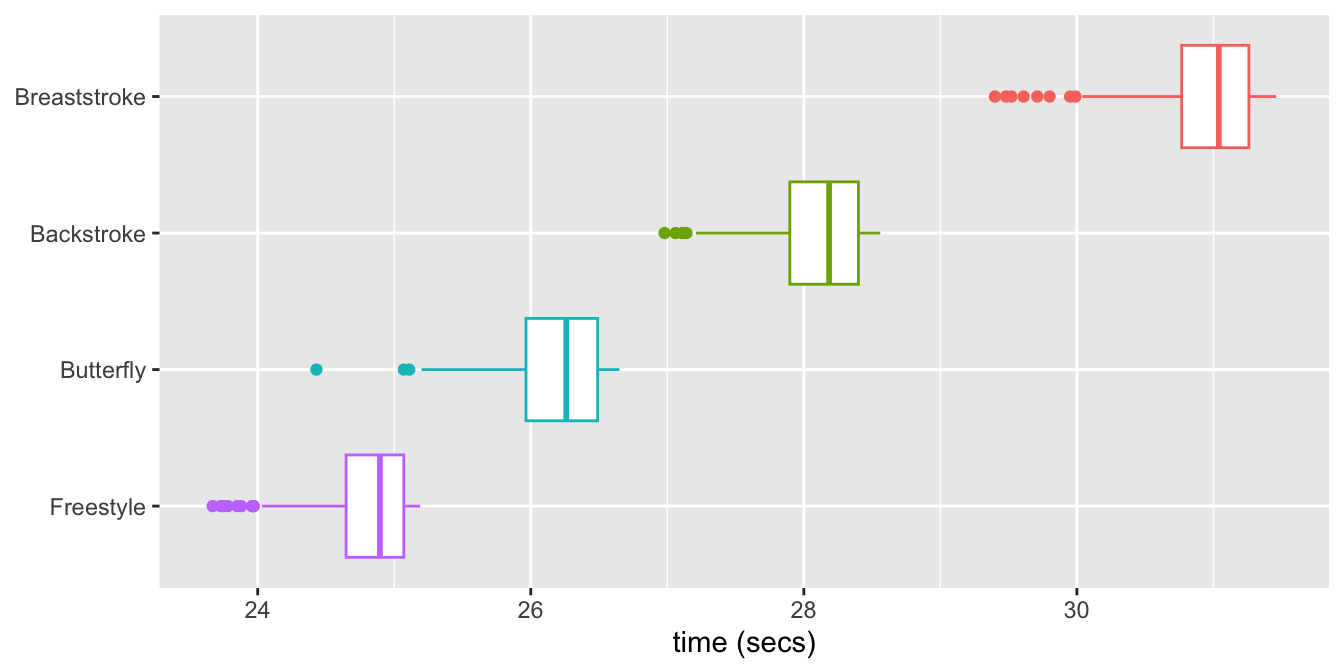

The graphic suggests an overlap between female butterfly and freestyle swimmers that was suspected but not confirmed amongst the males. Drawing only the times for women as boxplots in Figure 20.4 provides confirmation. Sarah Sjöström swam an incredible time for the butterfly of 24.43 seconds in the 2014 Swedish Championships. The asymmetric pattern of the boxplots is to be expected, distributions of best times are skewed to the left.

Figure 20.4: Boxplots of the best times by women for the four 50 m events

Do the same patterns apply for the longer standard distances of 100 m and 200 m? It turns out that the separations between the four strokes increase for both sexes, except for backstroke and butterfly where there is increasing overlap. Figure 20.5 shows this for the 200 m events.

Figure 20.5: Best times for the four 200 m events achieved by men and women

The 200 m LCM races include three turns and the turn rules are different for the four strokes. In particular, breaststroke and butterfly swimmers must touch the end with both hands at the same time, while freestyle and backstroke swimmers can touch the end with any part of their body. This explains at least partly why backstroke times catch up on butterfly times.

One point stands out in Figure 20.5, the superb pre-1980 time in the women’s 200 m breaststroke. Checking with the results for the 1971 6th Pan American games on the web revealed that Lynn Colella won both the 200 m breaststroke and the 200 m butterfly, but the FINA database recorded her butterfly time as a breaststroke time. Looking at the differences between the butterfly and breaststroke times overall, it is clear that there would be no traditional breaststroke swimmers in competitions any more had the butterfly not been declared a separate stroke.

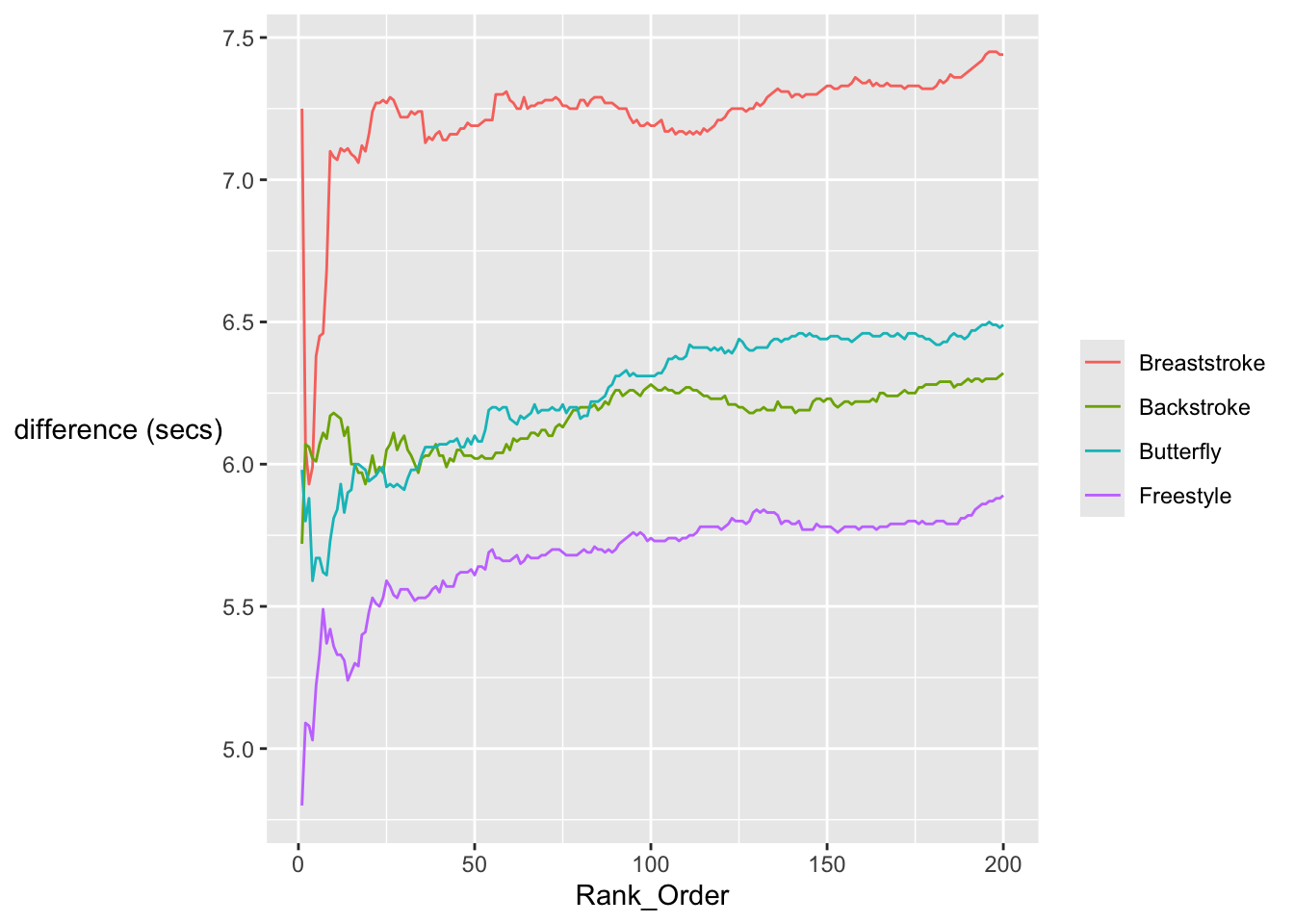

The performances of men and women can be compared by plotting the time differences between the swimmers of the same rank order for an event. Figure 20.6 shows this for the four 100 m events.

Figure 20.6: Time differences between men and women for the four 100 m events by rank

The display suggests that the very best women are a bit closer to the very best men in time and that the difference between the sexes increases as ranking increases. The big exception to this is the breaststroke, due to Adam Peaty’s 2019 world record of 56.88 seconds. In general, differences between equal ranks increase if one group is bigger than the other.

Differences in times between events are affected by the popularity of the events amongst the swimmers. This can be seen, for instance, in the numbers of swimmers taking part in the heats for the events at the 2019 World Championships (FINA (2021)). There were 41 in the men’s 4x100 m medley and 134 in the men’s 50 m freestyle. The corresponding numbers for the women were 26 and 106.