14.1 How do Darwin’s finches differ?

Darwin visited the Galápagos Islands in 1835 as part of his voyage on HMS Beagle. He collected many specimens, including birds he described as species of finches. Later researchers decided they are passerine birds belonging to the tanager family. Although Darwin collected finches, he only decided how important they might be a few years later. There is much written on Darwin’s finches and anyone with a deeper interest should read the book by Peter and Rosemary Grant (Grant & Grant (2014)), describing their forty years of detailed investigations on one small island. There is also an earlier populist book about the Grants’ work (Weiner (1994)).

The Galápagos Islands are fairly isolated from the rest of the world and relatively similar to one another, so Darwin was surprised at the numbers of different species of finch he identified. Classifying the species and investigating how they evolved is still part of ongoing research. A crucial feature is the size and shape of the beaks of the birds. Several datasets of measurements are available from the Dryad Digital Repository. Some have more information, some less. In this chapter morphological data from the Snodgrass and Heller Stanford expedition of 1898-99 to the Galápagos Islands are investigated (Snodgrass & Heller (1904), and Snodgrass & Heller (2008) for the data), as more features were measured and there were fewer missing values. The dataset is in the R package hypervolume (Blonder (2019)) called morphSnodgrassHeller.

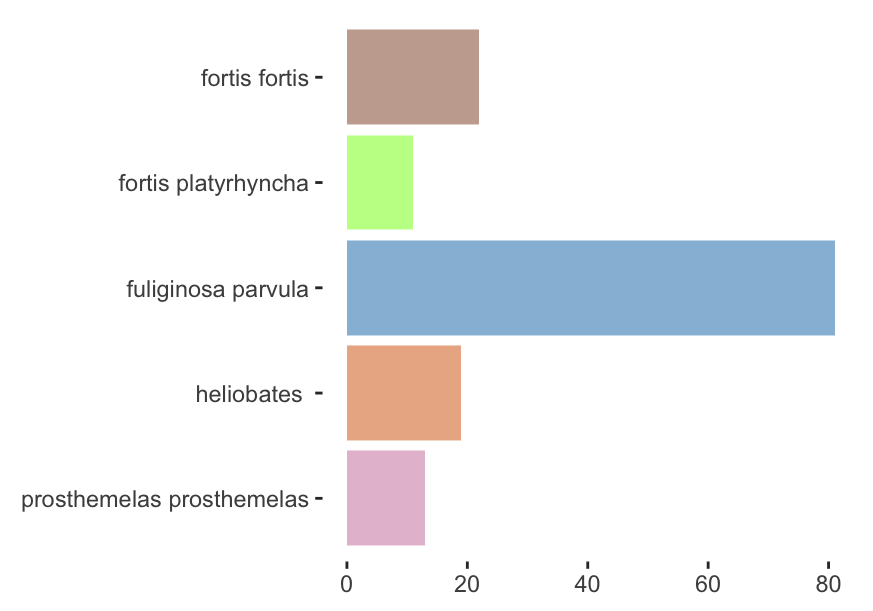

The first few plots display finches from the biggest island, Isabela, showing only species of the genus Geospiza with at least 10 birds (four species are excluded). Only birds with complete sets of measurements are included (so sixteen are not). Figure 14.1 shows the numbers of the five species in the subset. There are more specimens of Fuliginosa parvula than of the other four species combined.

Figure 14.1: Numbers of finch species from Isabela Island with at least ten birds and complete data

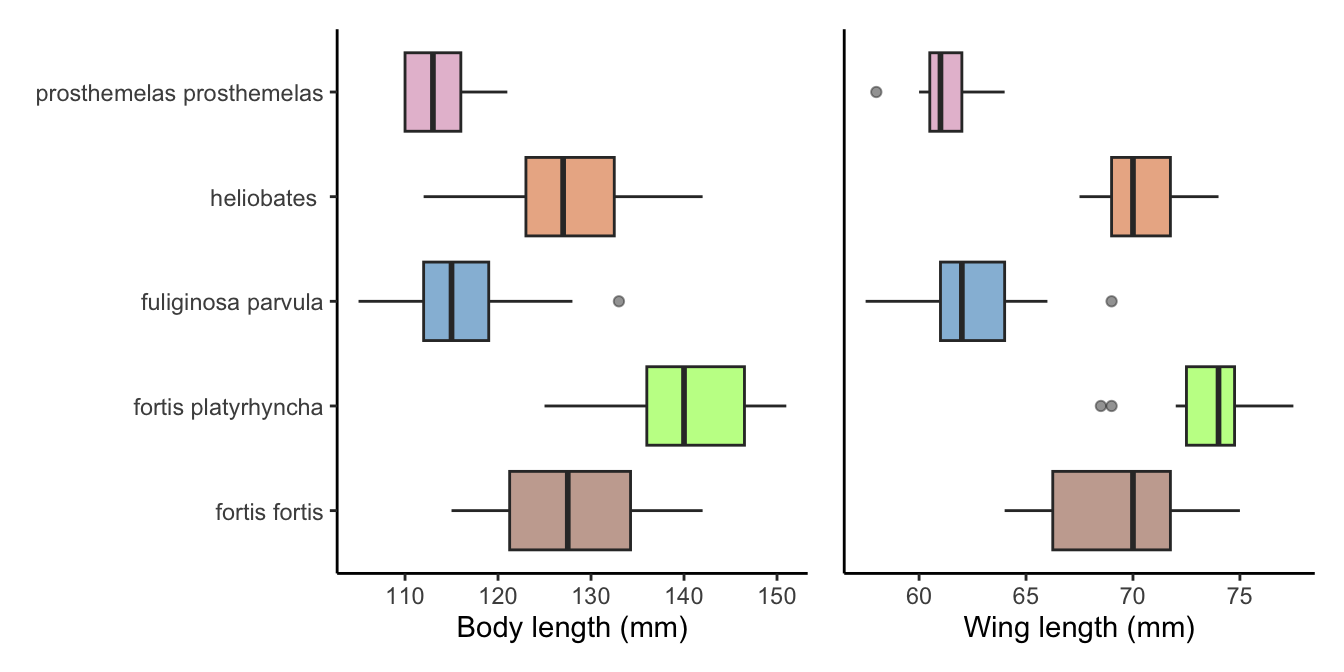

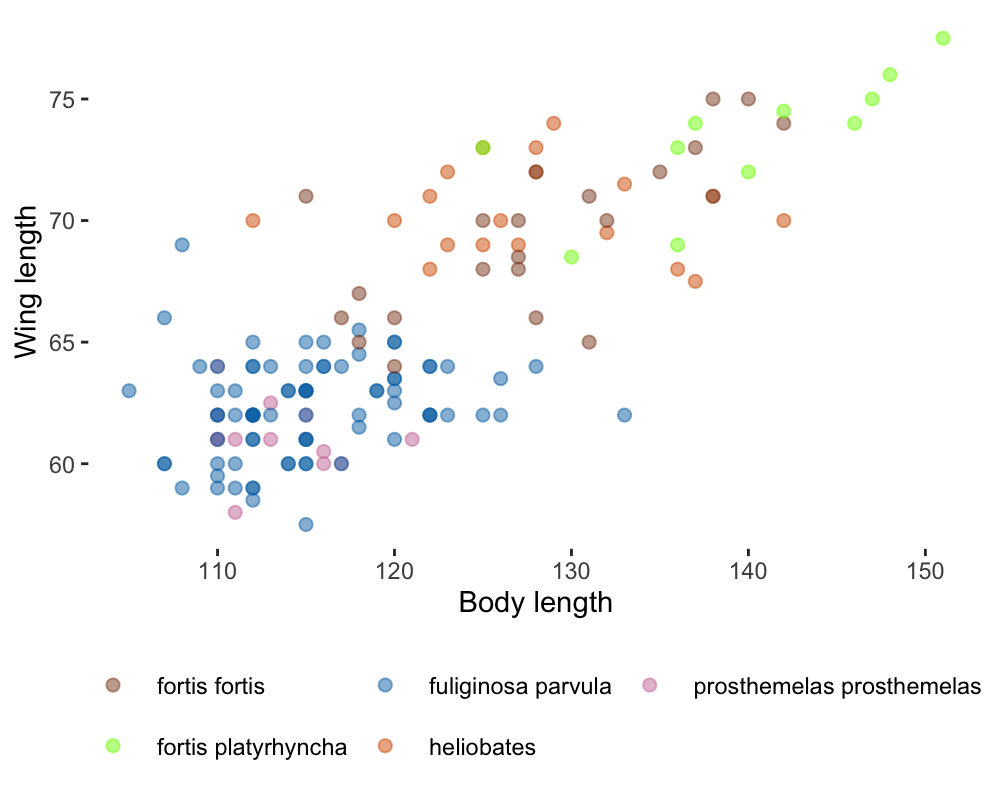

One way of comparing species measurements is to use boxplots. Figure 14.2 shows an example for body and wing lengths of the finches. The patterns are consistent. Two species are generally shorter than the others, two are in the middle, and one is bigger. The low numbers in each of the groups and the overlaps make firm conclusions based on Figure 14.2 difficult. Displaying the two variables together in a scatterplot might show if the variables separate the groups. The two variables together appear to separate some of the species pairs, but there is clearly some overplotting, so caution is necessary. A check confirms that 17.1% of the pairs of values are duplicates.

Figure 14.2: Body and wing lengths for the five species from Isabela Island

Figure 14.3: Scatterplot of wing length and body length for the five species from Isabela Island

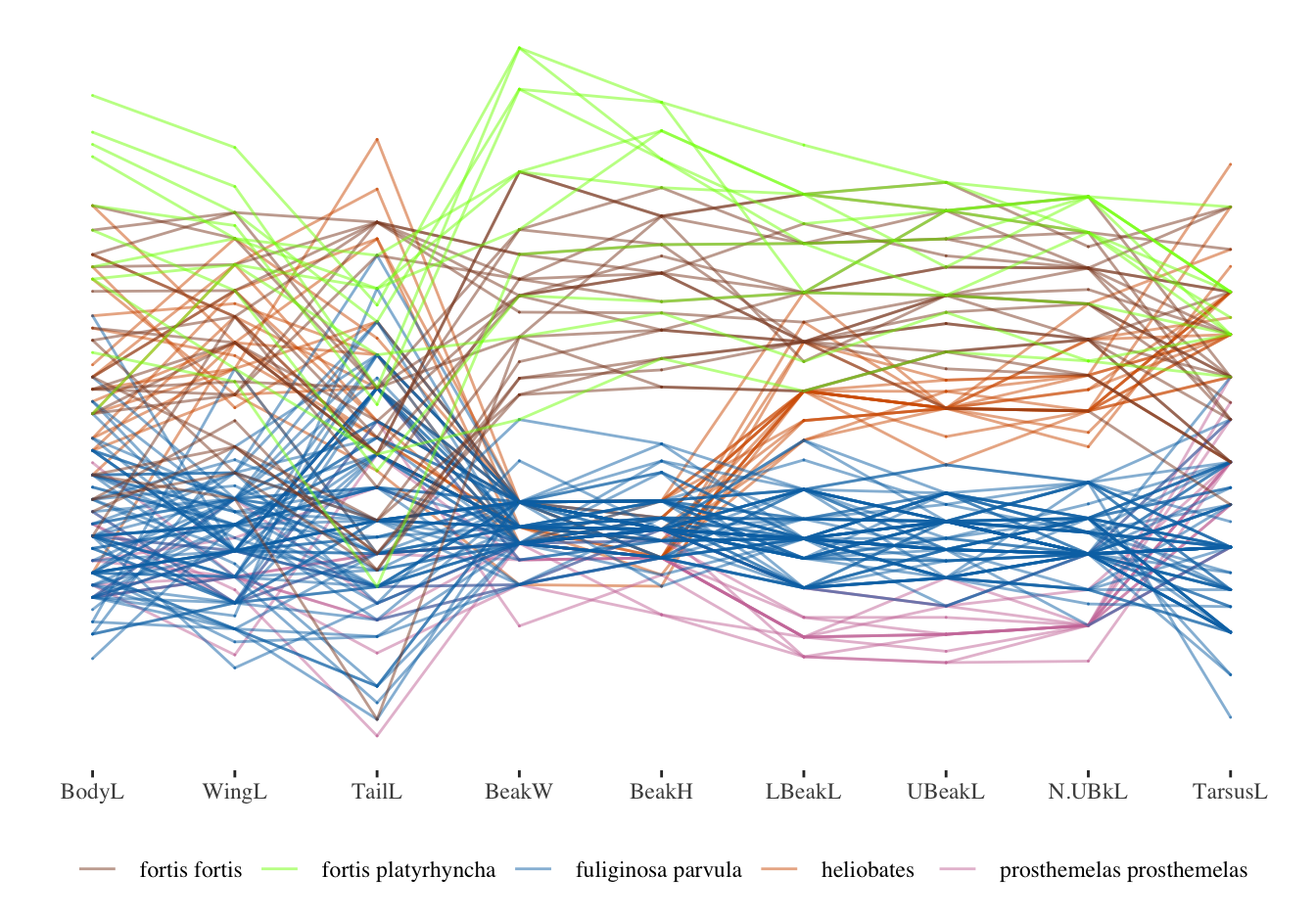

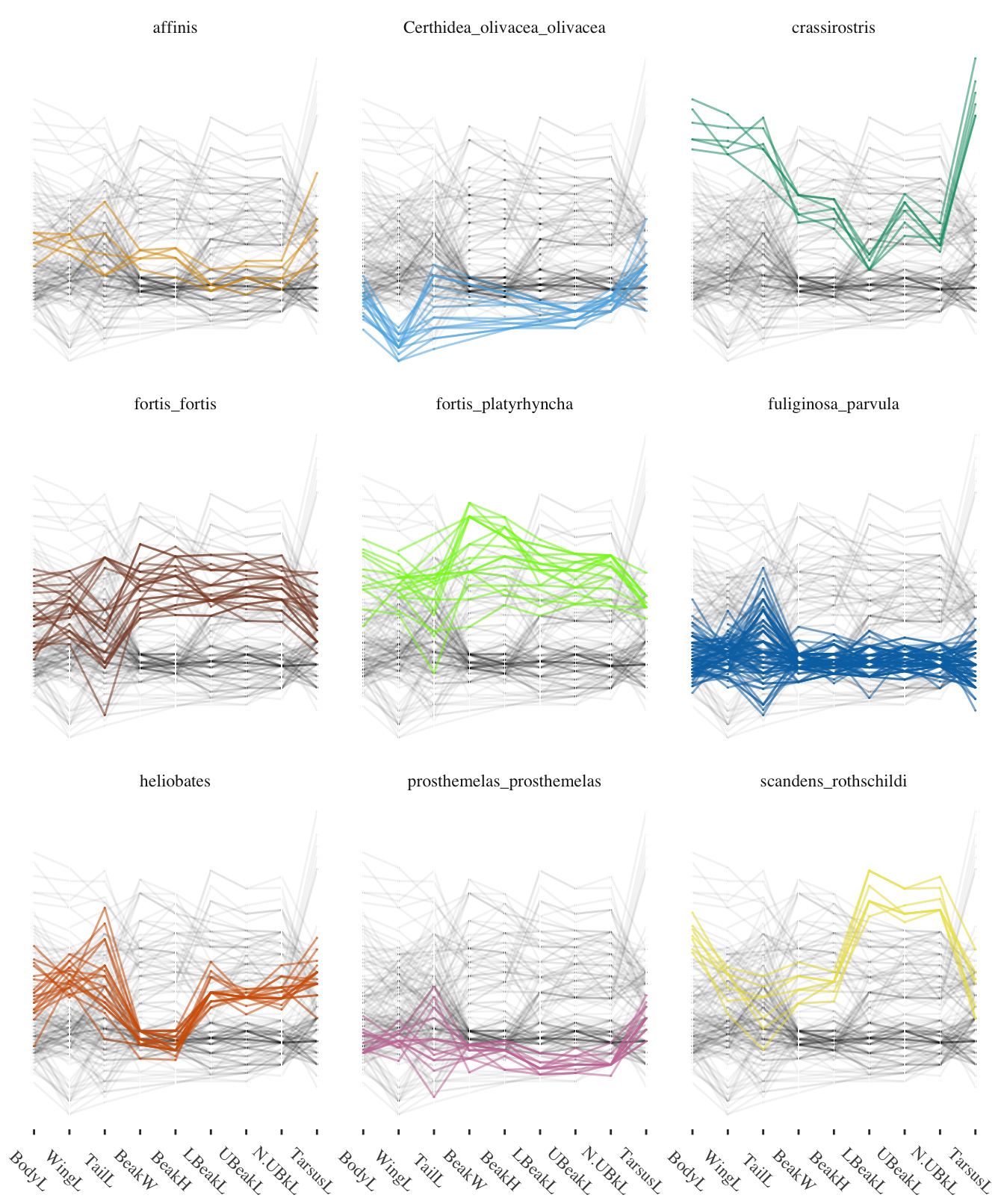

Other variables could be more discriminatory. The parallel coordinate plot in Figure 14.4 uses all nine measurements available.

Figure 14.4: Parallel coordinate plot of nine measurements of five Galápagos finch species from Isabela Island

The first two beak measurements of width and height (BeakW and BeakH) separate the two bigger species from the other three. The following three variables (LBeakL, UBeakL, and N.UBkL, also beak measurements, the last being the distance from nose to upper beak) separate the smaller species from one another. The two bigger species might be separated using a multivariate technique, but these two species are considered to be related subspecies, so demonstrable differences are unlikely. Having all the beak measurements together in their order in the dataset turns out to be informative. Alphabetic order or a random order of the nine variables would not be so effective.

What about the other four species on Isabela? Drawing separate parallel coordinate plots for all nine species and including all 195 birds in Figure 14.5 reveals that three of the extra species are distinct in some way from the other eight. In each plot the rest of the dataset is drawn in a transparent black in the background, ghostplotting. The species crassirostris has longer body and tarsus lengths than the other species, Olivacea olivacea has the shortest wings, Scandens rothschildi has the longest upper and lower beak measurements.

Figure 14.5: Parallel coordinate plot of nine measurements of nine Galápagos finch species from Isabela Island