6.1 How good are the data?

There is much data on the changing events at the Olympic Games (IOC (2022)), the new countries taking part, and especially on the improved performances of the participants over the years. Two datasets are studied for the Summer Olympics, one with performance data and one with no performance data but a more complete list of competitors.

The performance dataset for the Summer Olympics from 1896 to 2016 was scraped from the web in advance of the 2020 games that took place in 2021 because of the Covid pandemic. The data were used for commenting on the shape of the trend in improvement and not for any detailed analysis and were made available on request. A closer look uncovered a number of problems and illustrates how graphics can be used to support checking, editing, and restructuring data, as well as for exploring and displaying results.

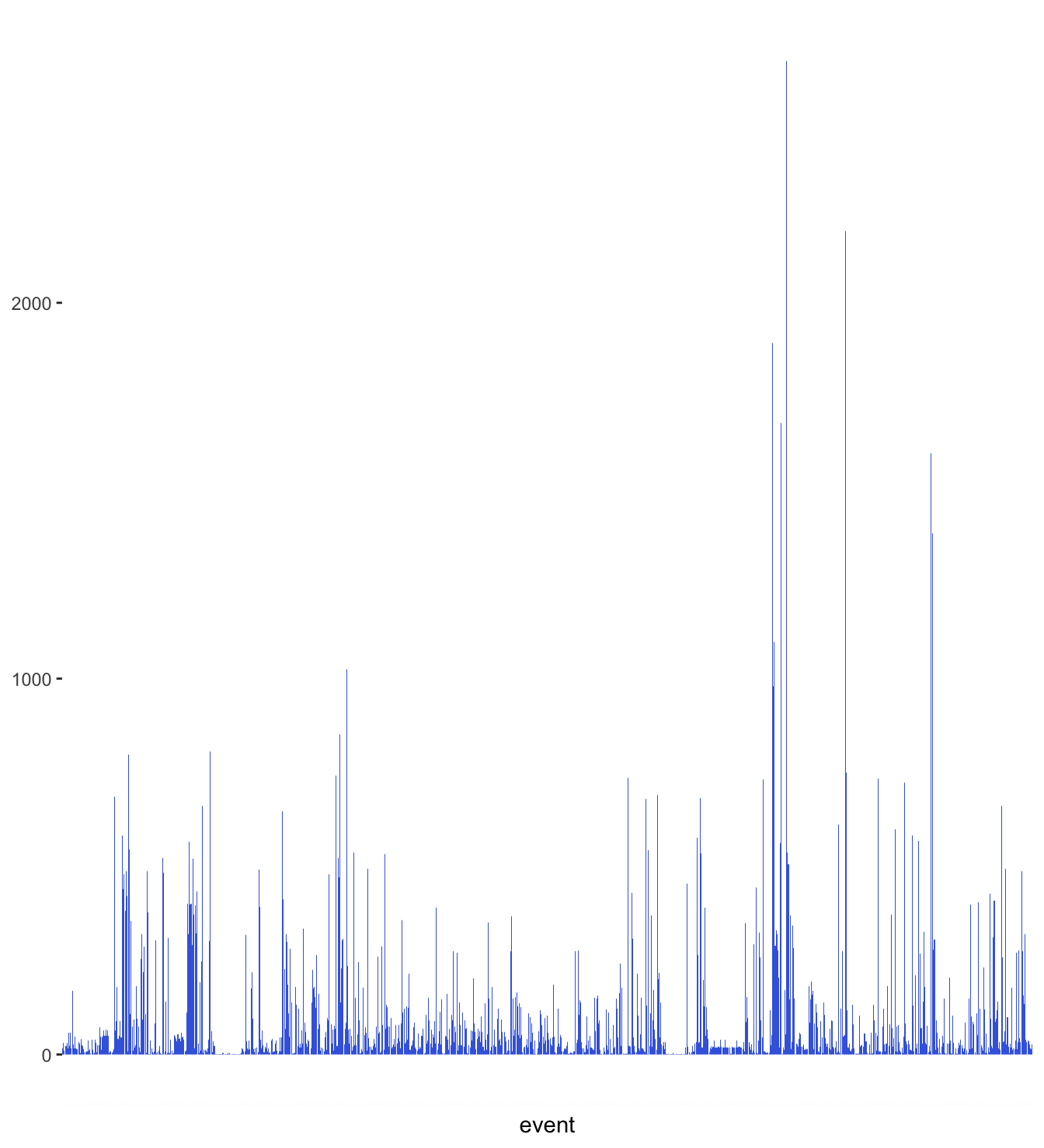

The performance dataset had almost 110000 entries. A barchart of the over 1100 events reported there (Figure 6.1) reveals a long list with numbers of participants ranging from 1 to 2644. Some events only took place at one Olympic Games and there were various alternative spellings and misspellings of events, which is why there appear to be so many.

Figure 6.1: Summer Olympic events by total numbers of participants in the Games of 1896 to 2016, ordered lexicographically (the default), based on the first dataset

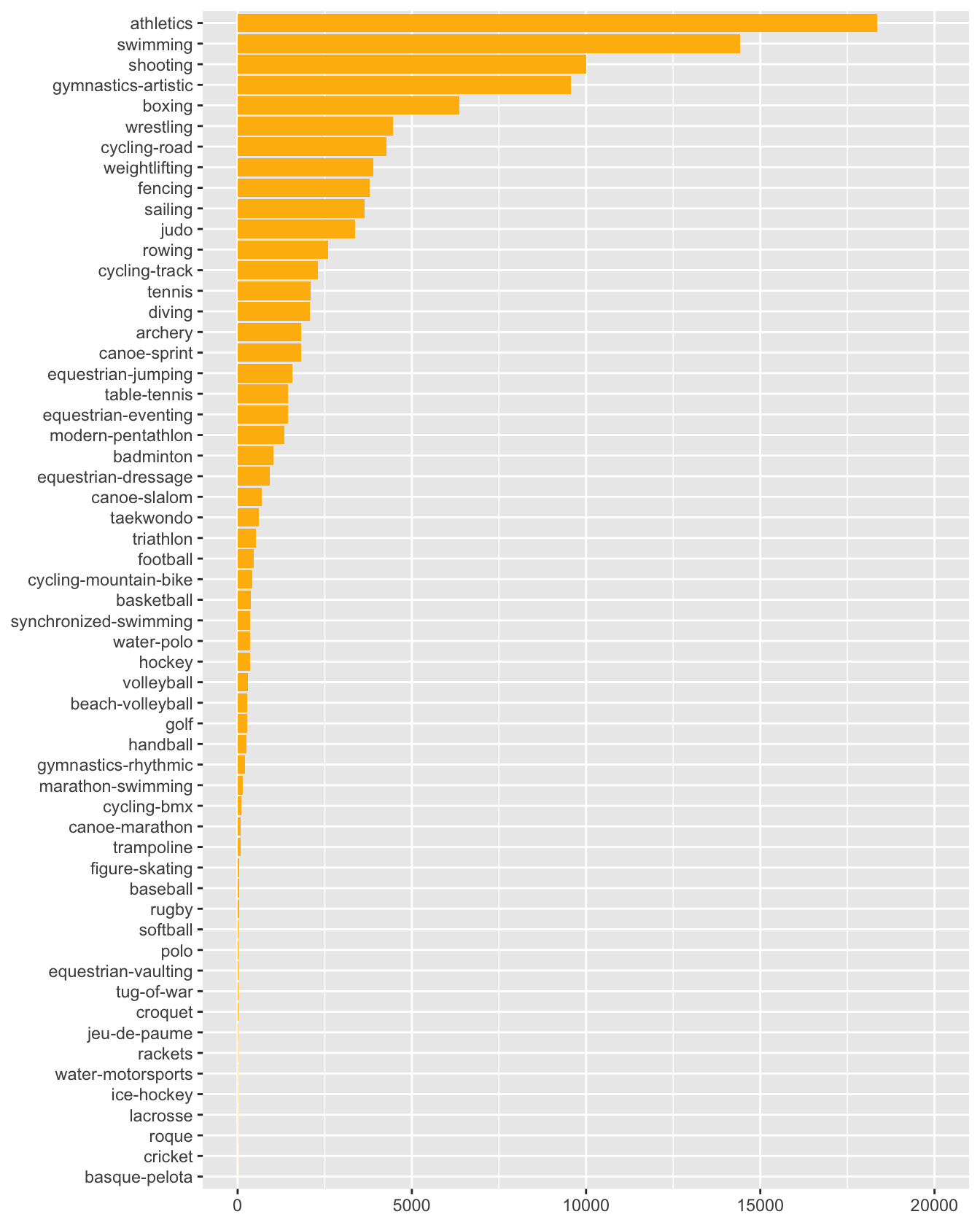

Events are grouped in sporting disciplines and looking at those instead also gives a surprisingly long list, ranging from athletics and swimming to cricket and basque-pelota. The top two disciplines in terms of participants, athletics and swimming, include many different events, as do some of the other disciplines.

Figure 6.2: Summer Olympics sporting disciplines by total numbers of participants in the Games of 1896 to 2016, based on the first dataset

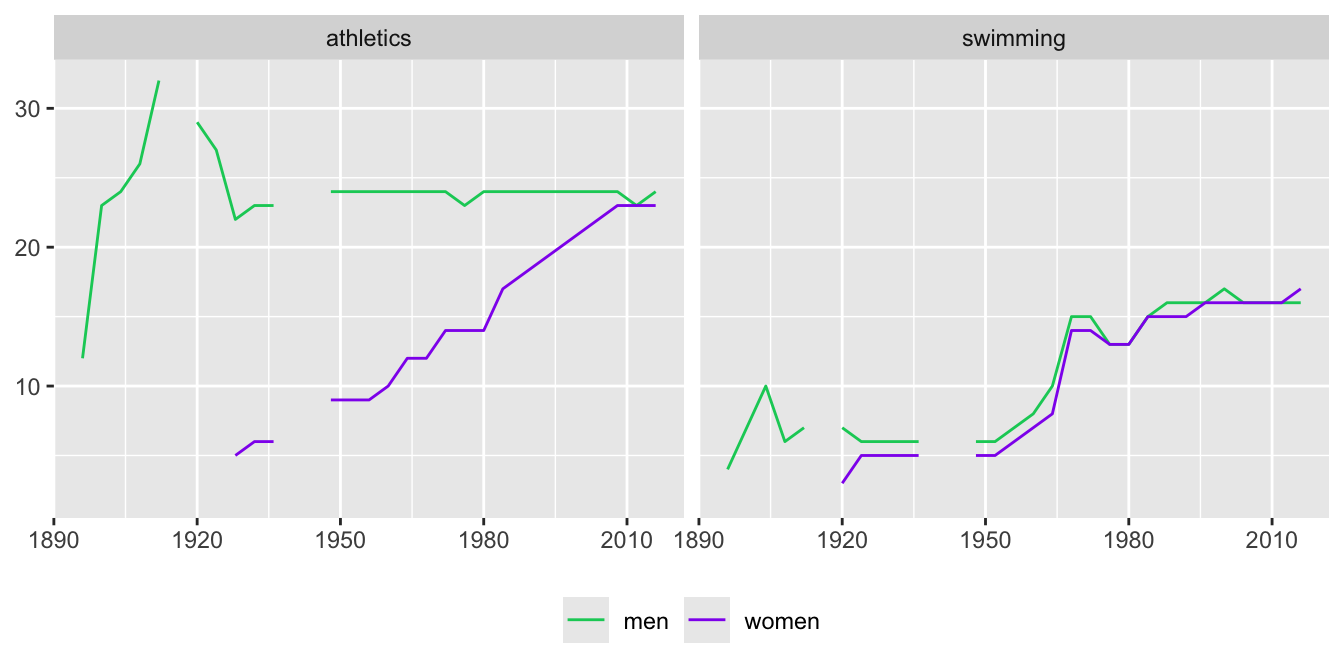

There are events for men and for women, and there are mixed and open events. Concentrating on the two most frequent disciplines, athletics and swimming, excluding mixed and open events, and restricting the dataset to gold medal winners gave Figure 6.3 showing the numbers of events at each Olympic Games. The patterns for the two disciplines are very different. After initial peaks before and just after the first World War, the number of athletics events for men barely changed. The number of athletics events for women increased steadily from a very low start in 1928. In swimming, the numbers of events for men and women followed similar paths from 1924 on.

Figure 6.3: Numbers of athletics and swimming events for men and women at the Summer Olympics from 1896 to 2016

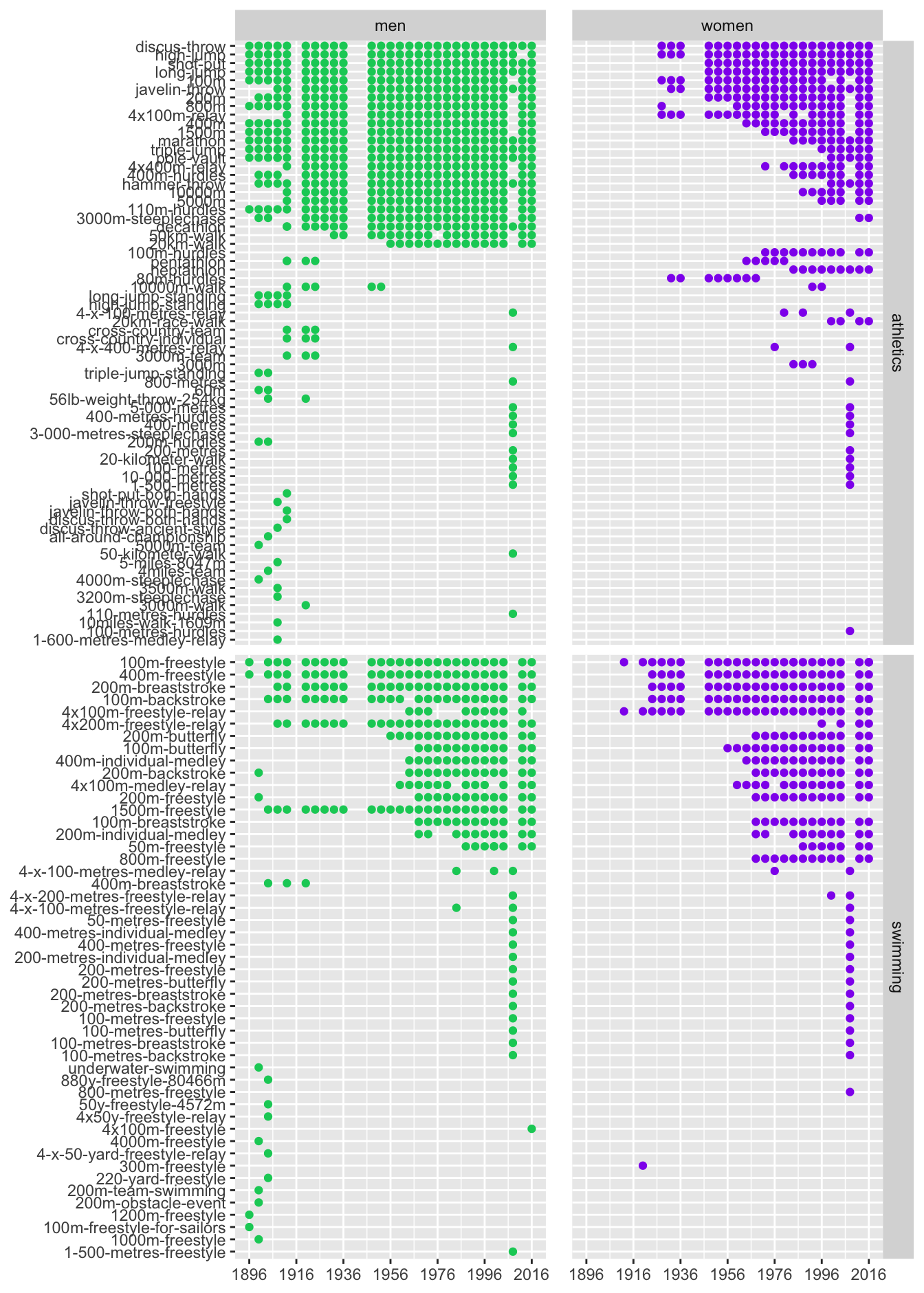

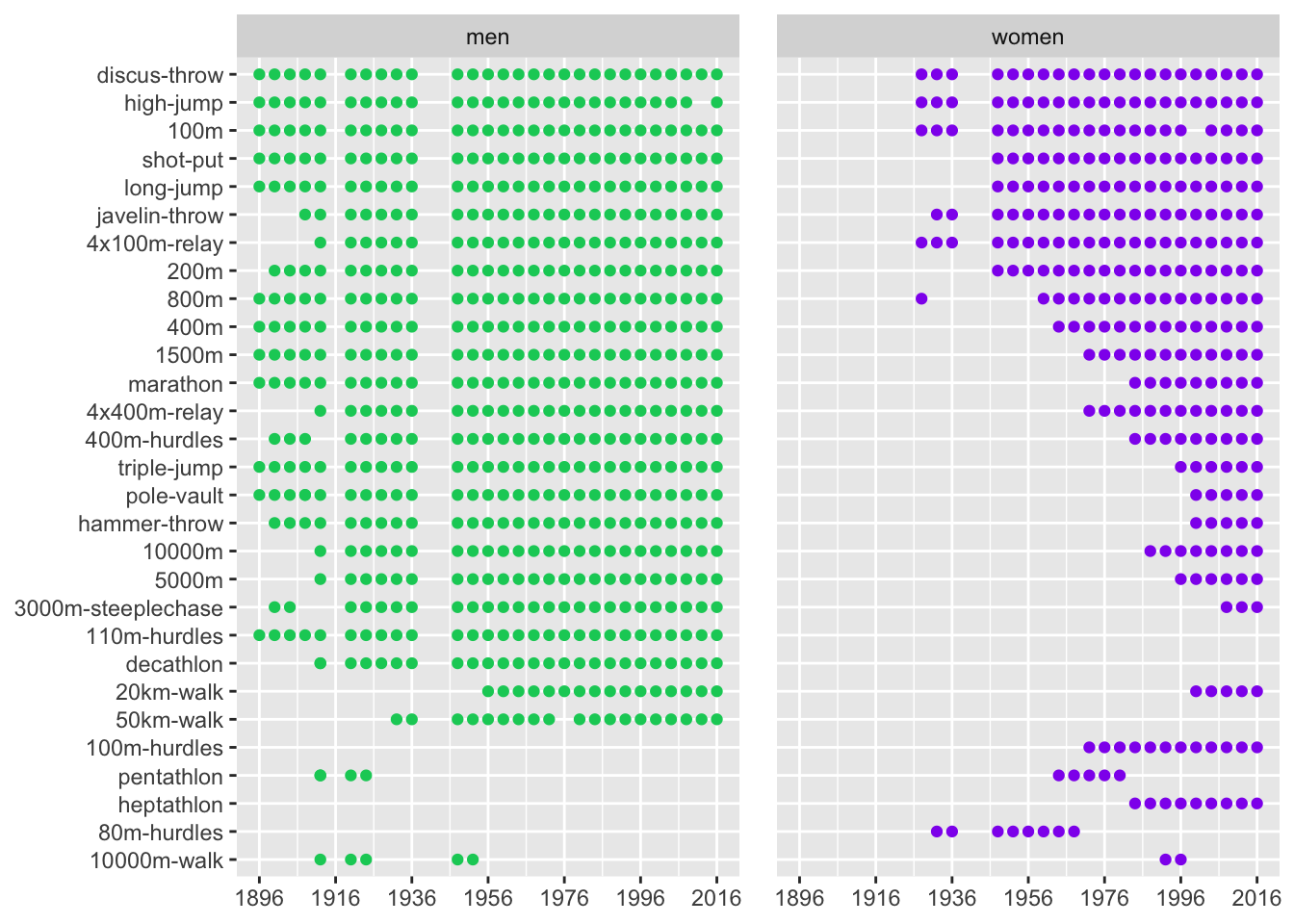

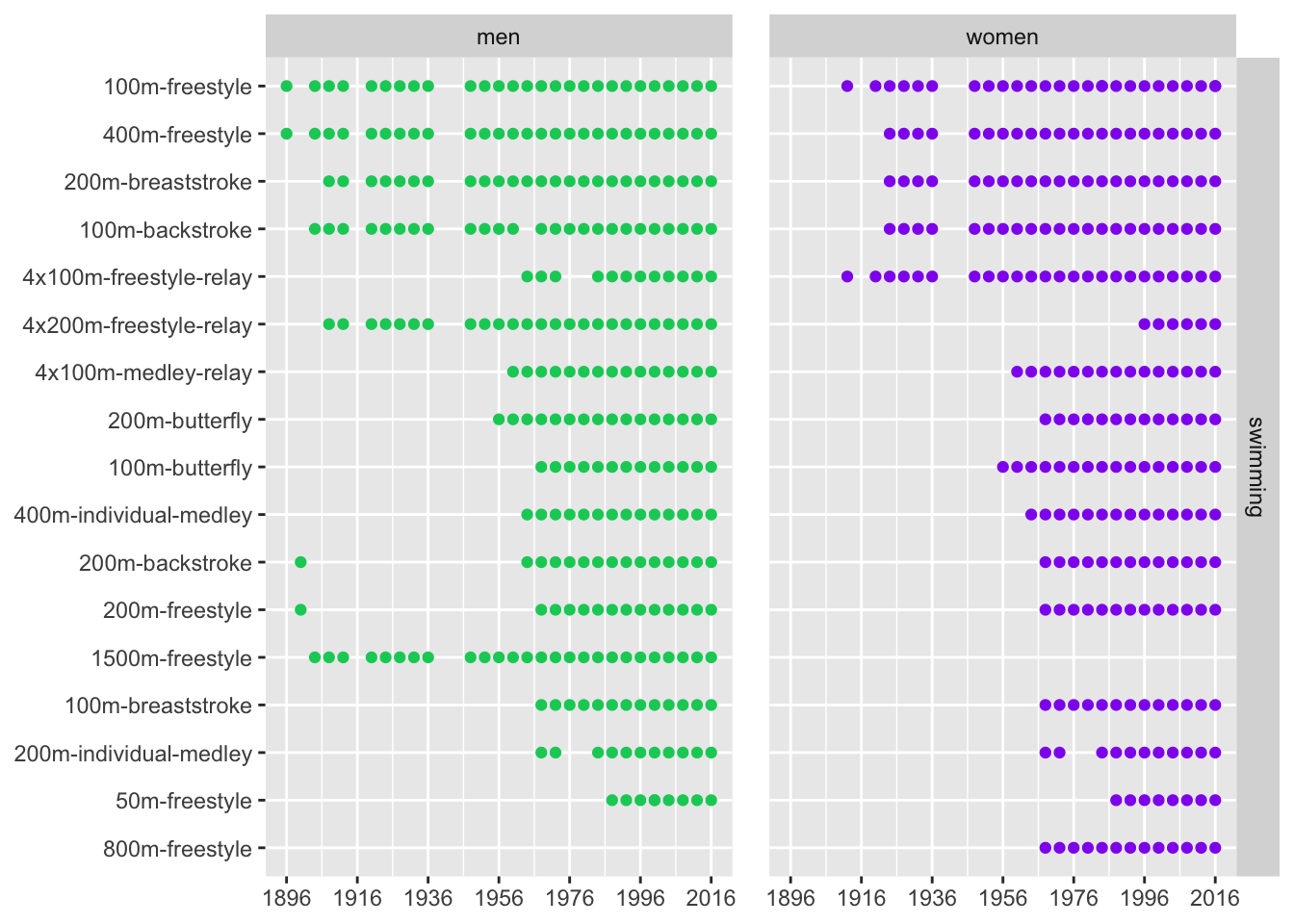

Figure 6.4 has more detail, showing which events took place for men and for women at which games. It was drawn to investigate why there appeared to be so many events listed. Despite the small print, two problems can readily be seen. The long line of dots to the right of each plot and the matching gaps above suggest that there was an issue with how athletics and swimming events were named at Beijing in 2008. The data source for Beijing used “-metres”, where the sources for other Olympics used “m”. The straggly lines to the left of the two plots for men show that some events only took place at early games (e.g. long-jump-standing and underwater-swimming). A minor issue is that there are individual gaps that will need to be investigated further.

Comparing the top two displays for athletic events, it is clear that women did not take part until much later than men. Athletic events for women began at the 1928 Olympics. Comparing the two displays on the right shows that swimming events for women began earlier, at the 1912 Olympics. Why were women allowed to swim before they could run?

Figure 6.4: Athletics and swimming events for men and women for which gold medals were awarded by Olympic year, ordered by numbers of gold medals awarded

After fixing the event names for the Beijing Olympics and setting aside the early events, displays were drawn separately for athletics and swimming (Figures 6.5 and 6.6). The correcting code was applied to the whole dataset and some of the corrections for Beijing fixed other minor issues. The ordering of the events is a little different from that in Figure 6.4 because the corrections have changed the total numbers of gold medals awarded for events.

Figure 6.5: Athletic events by Olympic year after amendments

Some events were only for men and some only for women. Men compete in the decathlon of ten events, whereas women compete in the heptathlon of seven events (and in earlier Games only in the pentathlon of five events). Men run the 110 m hurdles, while women run the 100 m hurdles (and formerly the 80 m hurdles). The women’s pentathlon and the women’s 80 m hurdles were excluded from further analysis. Other events that have taken place rarely (defined here as less than six times for men or women) were also excluded. There were gaps due to events not taking place or medals not being awarded. The men’s 50 km walk took place at all Games from 1932 to 2016 except for 1976. The winner of the men’s high jump in 2012 was later disqualified for doping offences and the other medals promoted in 2021. That had not been done at the time the dataset was scraped and so there was no gold medal winner and no data point in Figure 6.5. For a number of reasons related to doping, no gold medal was awarded for the women’s 100 m in 2000.

The 800 m for women stands out as first taking place at the Amsterdam Games of 1928 and then not again until the Olympics in Rome in 1960. The men in charge of the Olympic Games decided that the event was too strenuous for women and were supported by some highly dubious reporting in the newspapers (English (2015)). According to Robinson (2012), Harold Abrahams, the famous English runner, Olympic official, and journalist, said “The sensational descriptions are much exaggerated I can assure you.” Others must have held other opinions.

Figure 6.6: Swimming events by Olympic year after amendments

Since 1996 women have swum the same events as men, with one exception. The men’s longest freestyle event was 1500 m, while the women’s was 800 m. Interestingly, for the first time at the Tokyo Olympics of 2021, both races are now swum by both sexes.

Two striking gaps are apparent in men’s swimming events. Both the 200 m backstroke and freestyle were raced in 1900 in Paris and not again until 1964 (backstroke) and 1968 (freestyle). Results are missing for the men’s 400 m freestyle relay in 1976 and 1980, presumably a scraping problem. Results are not included for either men or women for the 200 m individual medley in 1976 and 1980, because the events did not take place at those Games.