17.1 Psychology of Privacy

(Brough et al. 2022) Consumers’ response to privacy notices (bulletproof glass effect)

Study 1: Managers expect a privacy notice will make customers feel more secure

- Since managers see that privacy notices as formal legal contract (i.e., binding agreements that dictate how a firm can collect, use and store data), they would expect that this formal contract-based approach can enhance consumers’ comfort in purchasing a firm’s product.

Studies 2, 3, 5: consistent with bulletproof glass increasing feelings of vulnerability (despite the protection offers), formal privacy notices can decrease consumer trust, and purchase interest (despite objective protection emphasis)

On the one hand, privacy is considered a social contract (Consumer perception of privacy invasion versus respect is governed by norm), and firms that respect these expectation can increase consumers’ trust (McCole, Ramsey, and Williams 2010) and increase purchase intention(Eastlick, Lotz, and Warrington 2006), and those that violate these norms will receive negative WOM (Miyazaki 2009). Benefits for consumers would not negate this negative reactions (T. Kim, Barasz, and John 2019). These social contracts can enhance trust (T. Kim, Barasz, and John 2019)

On the other hand, formal contracts (instead of social contract) can undermine trust (similar to the bulletproof in unusual settings) (D. Malhotra and Murnighan 2002): Evidence from that multi-round trust game that consumers are less likely to trust when a formal contract was created in the first round than without the contract.

Study 4: when consumers had a priori that they should be distrustful, the unintended consequence of privacy notice did not materialize.

- When consumers do not have potential harm in mind, when seeing a bulletproof glass (i.e., in unexpected situations), they will react more negatively than when some potential harm is expected

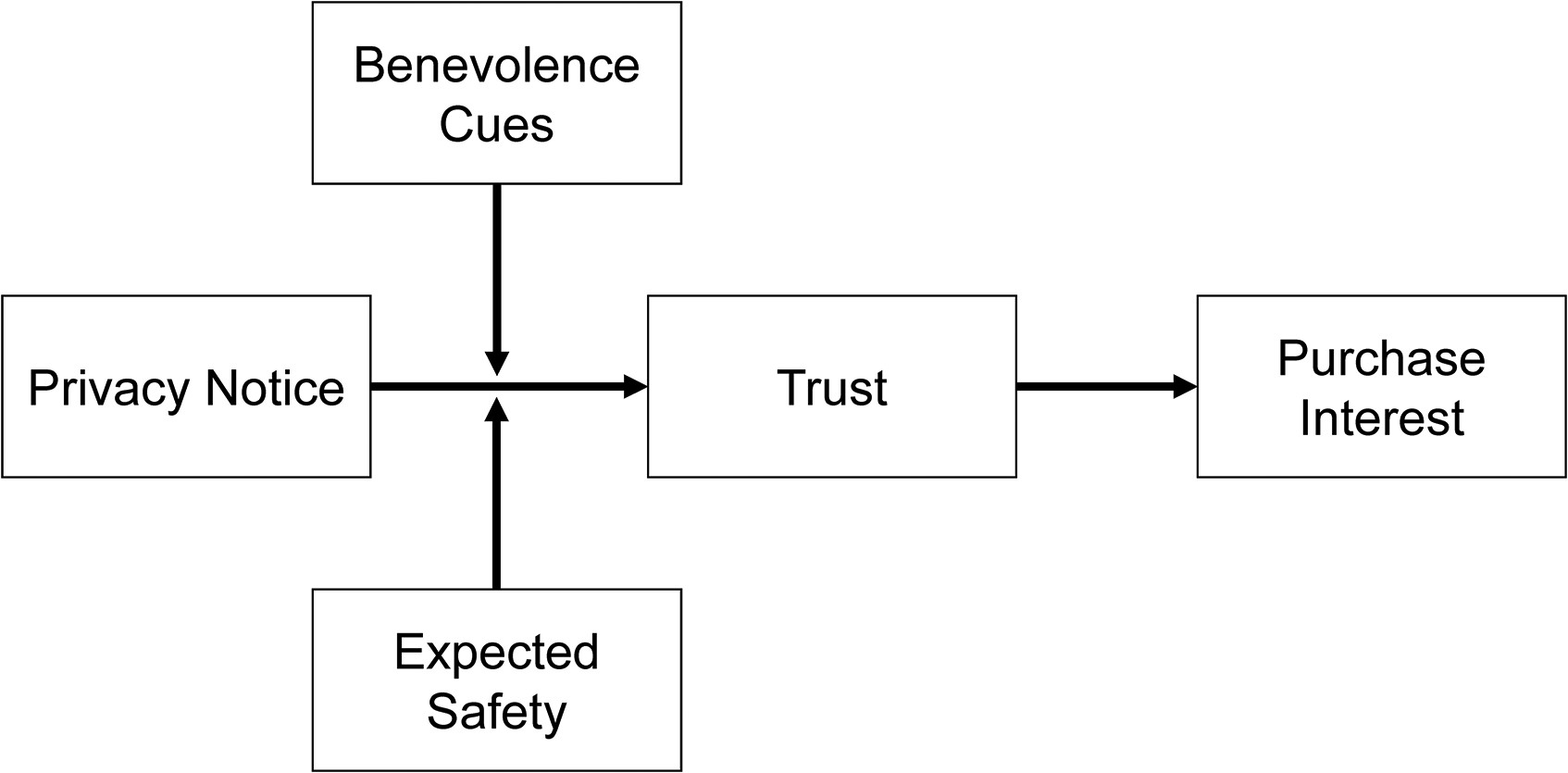

Study 5 and 6: when benevolence cues were added to privacy notices, the unintended consequence of privacy notice did not materialize

To increase trust, one can increase either benevolence or competence. Because benevolence-trust can induce consumers to view privacy notices as social contracts rather than formal contracts (as compared to using competence-trust).

Since benevolence-trust is affective where as ability-trust is cognitive, we can use LIWC to score whether a privacy notice regarding its proportion of words that reflect affect process and proportion of words that reflect cognitive process

Study 7: the presence and conspicuous absence of privacy info are enough too in decrease purchase intent.

Use Apple’s privacy nutrition labels to examine the presence and conspicuous absence of a privacy notice in terms of triggering decreased purchase interest.

Apps were not required to include privacy notices (between 08/2017 and 05/2018), only half of the apps included a privacy policy link (Story, Zimmeck, and Sadeh 2018)). In 12/2020, Apple mandated privacy labels in the App Store. Hence, (Brough et al. 2022) found that apps with a privacy notice conspicuously absence or present decease app downloads as compared to those without privacy notice.

Even though previous study posits that transparency regarding customer data can reduce perceived vulnerability (Kelly D. Martin, Borah, and Palmatier 2017), (Brough et al. 2022) posit that privacy notices can make costumers feel more vulnerable (similar to the bulletproof glass analogy)

The “bulletproof glass effect” is the increased purchase interest resulting from exposure to a privacy notice” (Brough et al. 2022, 740)

When consumers notice that their data have been collected without consent, click-through rates decrease (T. Kim, Barasz, and John 2019; Aguirre et al. 2015)

Consumers prefer to purchase from website with higher levels of privacy protection (J. Y. Tsai et al. 2011)

Even though consumers were predicted to be rational in their response to privacy-related info, consumers are more malleable and less intuitive: Consumers are willing to tradeoff privacy in response to

architecture and framing (Adjerid, Acquisti, and Loewenstein 2019; Brandimarte, Acquisti, and Loewenstein 2013)

small inconveniences or incentives (Athey, Catalini, and Tucker 2017)

greater perceived control over personal info (Mourey and Waldman 2020; Tucker 2013)