38.3 Channels and Customer Management

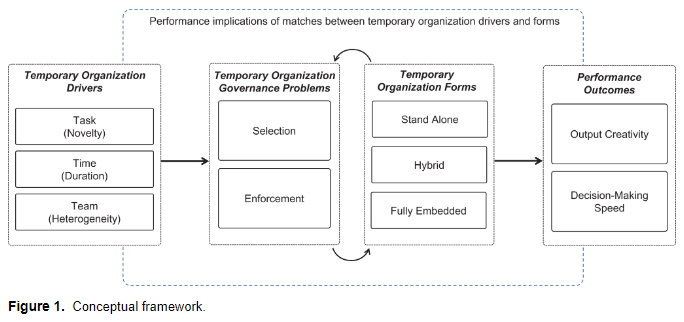

(Hadida, Heide, and Bell 2018) The temporary marketing organization

A temporary organization is defined as “temporally bounded group of interdependent actors formed to perform a complex task.” (C. M. Burke and Morley 2016, 1237)

- “temporally bounded” = “institutionalized termination”

“Stand-Alone” Temporary Organization: Discrete time horizon (also known as stand-alone)

Different from Joint venture (no past), Start-up (no past), Permanent organization.

Absent of (1) history of interaction between members (might induce info asymmetry regarding task ability -> self-selection to send signals, and require more enforcement mechanisms, but also because of the discreteness nature, this can be hard) (2) future.

Hybrids and fully embedded temporary organizations: the role of context

Temporary can acquire a post or a future using

its members’ prior relationships

Being embedded within a permanent organization with organizational context (but have to be careful, because “strong” prior ties can have limited information access(Granovetter 1973), but can also serve as a good quality control - enforcement mechanisms, reducing principal-agent discrepancy)

Temporary organization drivers

Task: reason for being: “The greater the novelty of the task, the greater the need for organization-specific selection and enforcement mechanism, and the higher the likelihood of using a stand-alone temporary organization relative to hybrid and fully embedded forms.” (p. 7)

Time “The shorter the duration of the task, the lower the feasibility of crafting organization-specific selection and enforcement mechanisms and the higher the likelihood of using a hybrid temporary organization relative to standalone and fully embedded forms.” (p. 8)

Team (composition - heterogeneity of its members): “The greater the heterogeneity of the team, the greater the need for enforcement through low-powered incentives and the higher the likelihood of using a fully embedded temporary organization relative to hybrid and stand-alone forms

Portability and Exogenous Selection and Enforcement Effects

Portability: “selection and enforcement needs of a temporary organization may be portable or supplied exogenous, either from preexisting agent relationships (hybrid) or form the features of a permanent organization (fully embedded)” (p. 8).

“The greater the novelty of the task, the lower the portability of the selection benefits from a hybrid temporary organization and the greater the need for organization-specific selection mechanisms.” (p. 9)

“For a hybrid temporary organization, enforcement benefits are portable regardless of the nature of the task.” (p. 9)

“The portability of a fully embedded temporary organization’s selection and enforcement benefits is weaker than for those of a hybrid.” (p. 10)

Performance Outcomes of the Temporary Marketing Organization

Output Creativity (inherently linked to selection): “The closer the match between the novelty of a temporary marketing organization’s task and its selection efforts, the greater the creativity of its output.” (p. 10)

Decision-making speed (inherently linked to enforcement): ““The closer the match between the novelty of a temporary marketing organization’s task and its enforcement efforts, the greater its decision-making speed.” (p. 11)

- The over-organization in term of enforcement can have adverse consequences on decision-making speed (due to reactance - lower instrinsic motivation).

Managerial Implications: Task novelty, time pressures, team heterogeneity, as temporary organization form’s inputs.

Future Research Directions

Different forms of temporary organizations: current study’s classification based on dyadic vs. organization-levels norms might not be sufficient for future fine-grained analysis.

Structural embeddedness: different from relational embeddedness (between a principal and an agent) where structural embeddedness is about connections among mutual contacts.

Multilevel relationships (e.g., upstream suppliers, producers, downstream customer).

Micro level proprieties and processes:

TCA has many applications in marketing because

it focuses on exchange

survey-data

Problems to underutilized

Refinements to the theory are no well known

Empirical works are not well integrated

TCA is under the “New Insititutional Economics” paradigm (supplanted neoclassical economics)

TCA views firm as a governance structure

Assumptions

| Behavioral Assumptions | Transactional dimension |

|---|---|

| Bounded rationality | Environmental uncertainty |

| Opportunism | Asset specificity |

| Risk Neutraliity | Transaction Frequency |

Logic

If adaptability, performance evaluation, and safeguarding costs are absent or minimal, economic actors will choose market governance.

If internal organization expenses exceed market production cost benefits, enterprises will choose this.

Contexts to apply TCA

Vertical integration

Vertical inter-organizational relationships

Horizontal inter-organizational relationships

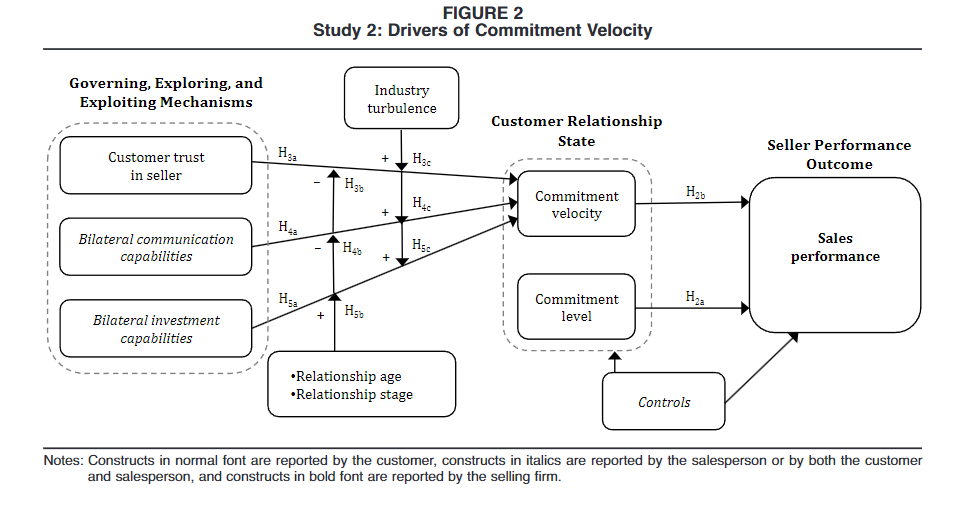

Commitment velocity: the rate and direction of change in commitment

Data

Study 1

Data: longitudinal (6 years)

Method: latent growth curve analysis

Commitment velocity is a predictor of performance

Study :

Data: Matched multiple-source data to see the antecedents of commitment velocity

Found customer trust and dynamic capabilities as antecedents, but less impactful as a relationship ages where as investment capabilities become more important.

Tenets

Exchange performance is influenced by both static and dynamic elements of relationship constructs, although dynamic elements are more important than static components for forecasting future behaviors and performance.

Depending on the relative contributions of a construct-specific collection of underlying time-varying processes, the growth trajectories of relational constructs (such as trust, commitment, and relational norms) are distinctive and path-dependent.

As relationships change, so do (a) the connections between relational constructs and (b) the relative weight of relational constructs in determining how trade outcomes are influenced.

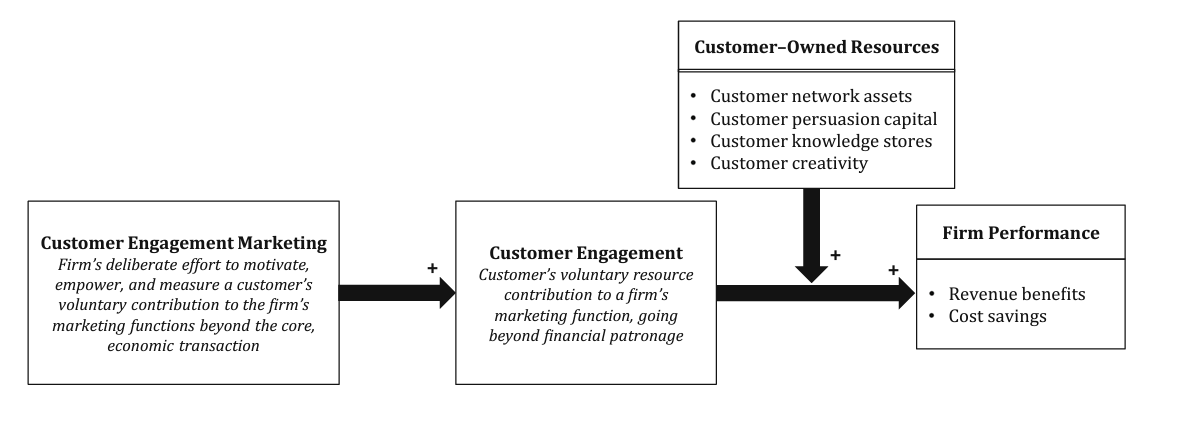

- Customer engagement marketing: “a firm’s deliberate effort to motivate, empower, and measure customer contributions to marketing functions” (p. 312)