8.3 Brand Equity

Brand equity was operationalized as …. of Perceived Quality, Brand Associations, Brand Awareness, Brand Loyalty:

a reflective construct (Yoo and Donthu 2001)

a formative construct of (Henseler 2017)

a consequence/outcome (preferable, and easier to argue with reviewers, but still not the consensus of the field)

Quantitative measure of brand equity:

W. A. Kamakura and Russell (1993)

Roland T. Rust et al. (2021)

(D. Mitra and Golder 2006): (need to read this paper)

Qualitative measure of brand equity:

brand and psychological distance: Congruence effect: “information is easier to process, which leads consumers to respond more favorably.” (Connors et al. 2020) “consumer spending higher when distance between consumer and brand matched with construal level of marketing communications.”

Value-added is the difference between a product’s price to consumers and the cost of producing it.

Whereas, brand equity is the difference between a branded product’s price to a generic product’s price.

This generic product can also have value-added in it in other forms (e.g., convenience)

Brand identity offers a value proposition to customers, where “a brand’s value proposition is a statement of the functional, emotional, and self-expressive benefits delivered by the brand that provide value to the customers” (D. Aaker 1996, 95).

Functional benefits are product attributes that deliver functional utility to customers, while emotional benefits are positive feelings customers feel when using the brand. Ads that provide emotional benefits are higher in effectiveness score compared to functional benefits ads (D. Aaker 1996, 98).

For example, Evian - “Another day, another chance to feel healthy” ad - which provides emotional benefits of feeling satisfied after a workout. Moreover, self-expressive benefits are when brands provide a means for consumers to express their self-image. A person/ consumer can have multiple roles which associate with multiple self-concepts. Such as a woman, a mother, an author. The difference between emotional benefits and self-expressive benefits can be subtle. Emotional benefits focus on feelings, private setting (e.g., feeling of watching a TV show), past-oriented (memories), transitory, after-use emotional; In contrast, self-expressive benefits focus on self, public settings (e.g., using cars or clothes to signal), aspiration or future-oriented, permanent (i.e., the self links to person’s personality), and during-use (wearing fancy clothes to signify a successful person). (cf. (D. Aaker 1996, 99))

With the advancement in mass production of high -quality products, quality is no longer a dimension of status signal (Holt 1998)

In the virality framework, the first and foremost driver is social currency. Social currency refers to things worth sharing. People share so that they can let others know that they are in the know. Sharing a new product to assimilate his or her identity with the product and its brand identity, customers are acquiring social currency. Moreover, brand identity is a driver of brand equity, which refers to the value portion that customers are willing to pay above the product’s utility value (practical value). Brand identity offers a value proposition to customers, where “a brand’s value proposition is a statement of the functional, emotional, and self-expressive benefits delivered by the brand that provide value to the customers” (Aaker, 1996, p. 95). Functional benefits are product attributes that deliver functional utility to customers, while emotional benefits are positive feelings customers feel when using the brand. Ads that provide emotional benefits are higher in effectiveness score compared to functional benefits ads (Aaker, 1996, p. 99). For example, Evian - “Another day, another chance to feel healthy” ad - which provides emotional benefits of feeling satisfied after a workout. Moreover, self-expressive benefits are when brands provide a means for consumers to express their self-image. A person/ consumer can have multiple roles which associate with multiple self-concepts. Such as a woman, a mother, an author. The difference between emotional benefits and self-expressive benefits can be subtle. Emotional benefits focus on feelings, private setting (e.g., feeling of watching a TV show), past-oriented (memories), transitory, after-use emotional; In contrast, self-expressive benefits focus on self, public settings (e.g., using cars or clothes to signal), aspiration or future-oriented, permanent (i.e., the self links to person’s personality), and during-use (wearing fancy clothes to signify a successful person). (cf. (Aaker, 1996, p. 99)) Hence, one can see that the brand identity portion that provides self-expressive benefits is social currency while exhaustively different from the brand identity portion that provides functional benefits (i.e., the practical value/ usefulness/ utility) .

We acknowledge that some might view usefulness/ utility as a dimension of brand equity (perceived quality): the perceived quality dimension can signal the true practical value. However, the practical value that drives virality is usually understood, experimented, experienced; while perceived quality is subjective comprehension that is hard to demonstrate. Moreover, quality used to be the status signal. However, with the advancement in mass production of high-quality products, quality is no longer a status signal dimension (Holt, 1998). Thus, we believe that the distinction between the two understandings should be appreciated.

(S. G. Bharadwaj, Tuli, and Bonfrer 2011; Larkin 2013; T. J. Madden 2006; Mizik and Jacobson 2008; Lopo L. Rego, Billett, and Morgan 2009) Customer-based brand equity is positively related to a company’s stock returns, market value, credit ratings, and leverage, and adversely related to idiosyncratic risk and earnings volatility.

(Tavassoli, Sorescu, and Chandy 2014)

Employee-based brand equity significantly affects executive pay.

Executives value being associated with strong brands and are willing to accept lower pay at firms that own strong brands.

This effect is stronger for chief executive officers and younger executives than for other executives.

8.3.1 Brand Loyalty

- (Berkowitz, Jacoby, and Chestnut 1978; Berkowitz 1978) reviews on Brand Loyalty: Measurement and Management by Jacoby and Chestnut 1978, which pioneered the idea of attitudinal and behavioral loyalty.

- The Loyalty Economy

- Loyal customers trump powerful brands

8.3.2 Brand Awareness

also known as brand familiarity

(Homburg, Klarmann, and Schmitt 2010) found that there exists a correlation between brand awareness and market performance. However, this link is mitigated by market features (product homogeneity and technological volatility) and organizational buyer characteristics (buying center heterogeneity and time pressure in the buying process)

8.3.2.1 Brand Prominence

Butcher, Phau, and Teah (2016) found that consumer views of the quality of luxury items are influenced by increased brand prominence, with quality and respondents’ status consciousness influencing the emotional value they obtain from luxury goods. Along with the direct influence of brand prominence, this emotional value has a significant impact on purchase intentions.

(J. K. Lee 2021) reduced emotionality correlates with high-status communication norm, evoking high-status reference groups.

Brand prominence: “reflects the conspicuousness of a brand’s mark or logo on a product.” (p. 15)

Brand prominence is “the extent to which a product has visible markings that help ensure observers recognize the brand.” (p.17)

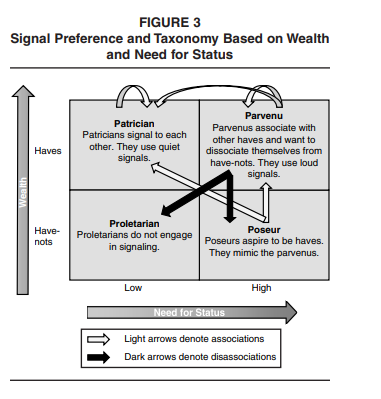

Consumers prefer quiet or versus loud branding because they want to associate vs. disassociate themselves with /from different groups of consumers.

Luxury goods are those that, in addition to any utilitarian value, confer status on the owner simply by being used or shown.

Need for status is the “tendency to purchase goods and services for the status or social prestige value that they confer on their owners.” (Eastman, Goldsmith, and Flynn 1999, 41)

What confers status is the evidence of wealth (i.e., wasteful exhibition = conspicuous consumption)

Upper-class members spend conspicuous things to distance themselves from the lower class (“invidious comparison”), whereas lower-class members consume conspicuously to align themselves with the higher class (“pecuniary emulation”).

Studies

Market data (Bag - LV and Gucci, Car - Mercedes, shoes - LV): inconspicuously branded luxury goods cost more than that of conspicuous branding.

Market data (knockoffbag.com and confiscated counterfeit goods from Thailand) counterfeiters copy the lower-priced, louder luxury goods to appeal to poseurs that want to emulate parvenus.

Survey (assume people to belong to certain groups based on zipcodes) Patricians pay a premium for signals that only other patricians can decipher

Survey (self-categorization to a persona) Social motives explain why groups choose loud or quiet luxury products. Poseurs are more inclined than parvenus to buy fake loud bags when given the chance.

8.3.3 Brand Associations

“different groups of people can have different or even contradictory associations with the same stimulus” (Wheeler & Berger, 2007)

8.3.3.1 Brand Meaning

Brand meaning is a subset of brand associations (brand associations can also have associations regarding attributes - perceived quality)

Batra (2019)

Brand meaning refers to “the complete network of brand associations in consumers’ minds, produced by the consumer’s interactions with the brand and communications about it.” (p. 535)

Endorsers are conduits of cultural meaning transfer.

Previous researchers conflated brand meaning with the narrower construct - brand personality.

Propose possible brand meaning items

sources of brand meaning (independent variables):

visual cues (advertising, packaging)

sensory cues (e.g., music)

human cues (e.g., endorsers)

8.3.3.2 Brand Image

Successful brand transferability typically depends on attribute similarity and personality similarity (image similarity). Since customers expect a firm’s technological competencies to transfer between products with similar makeups, an antecedent of a successful brand’s transferability is that products share similar attributes. On the other hand, image similarity is the “relationship of categories in terms of the images of the brands in them” (Batra et al., 1993). For instance, a brand in the entertainment industry with the image of being fun and exciting can potentially extend to soda production. Aaker and Keller (1990) have shown that transferability is higher for complimentary products and hard-to-make products, and no impact for substitutes products, while Batra et al. (1993) showed that brand transferability is higher for a product with a high match on the image (personality dimension) and on product attributes.

Batra and Homer (2004)

Nonverbalized personality association of celebrity endorsers on fun and sophistication (classiness) can increase consumer beliefs about a brand’s fun and classiness. (only under social consumption context, and match between brand image beliefs and product category).

And ad-created brand image beliefs only influence brand purchase intention, not brand attitudes.

X.-Y. (Marcos). Chu, Chang, and Lee (2021)

Prestigious brands whose brand image is associated with status and luxury, consumers’ attitude toward the product becomes more favorable and their willingness to pay a premium for the product grows as the distance between the visual representations of the product and the consumer increases.

Popular brands whose brand image is associated with broad appeal and social connectedness, the closer the distance, the more favorable is consumers’ attitude and the higher their willingness to pay a premium.

Chernev and Blair (2015)

CSR increases not only public relations and customer goodwill, but also customer product evaluation.

Consumers perceive that products from companies performed CSR to be better performing (even though they can experience and observe the products or when CSRs are unrelated to the company’s core business).

This effect is lowered when consumers believe that company’s behavior is driven by self-interest as compared to benevolence.

Hence, acting good (and people don’t know your true intent) can lead to better company’s performance.

L. Liu, Dzyabura, and Mizik (2020) built BrandImageNet (based on multi-label deep convolutional neural network model) to predict the presence of perceptual brand attributes in the consumer-created images (which is also consistent with consumer brand perception collected from survey). Hence,this model can monitor brand portrayal in real time to understand consumer brand perceptions and attitudes toward their and competitor brands.

8.3.3.3 Brand Personality

Jennifer Lynn Aaker (1997)

5 dimensions of brand personality:

Sincerity

Excitement

Competence

Sophistication

Ruggedness

Also offers a scale to measure brand personality

Brand personality is defined as “the set of human characteristics associated with a brand.” (p. 347)

Batra, Lenk, and Wedel (2010)

Previous research posits that brand with greater brand associations and imagery “fit” will more likely to have successful brand extensions

If the brand is “atypical” - associations and imagery are broad and abstract compared to the brand’s original product category, the brand will be more likely to succeed

This research offers a Bayesian factor model that can measure that brand-level and category-level random effects, which later helps measure a brand’s fit and atypicality.

Category personality can be masculine or feminine, etc. (Levy 1959)

Brand extension considers

Fit

Concrete product attributes

Abstract imagery or personality attributes

Atypicality

Grohmann (2009)

advancement on Jennifer Lynn Aaker (1997)

scale measuring masculine and feminine brand personality

Spokespeople shape masculine and feminine brand personality perceptions

brand personality-self concept congruence affects affective, attitudinal and behavioral consumer responses.

masculine and feminine brand personality contributes to the brand extension perception

More reference on Actual and the Ideal Self: Malär et al. (2011)

8.3.3.4 Brand Coolness

Warren and Campbell (2014)

Autonomy refers to “a willingness to pursue one’s own course irrespective of the norms, beliefs, and expectations of others” (p. 544)

Autonomy means diverging from the norm.

Properties of coolness:

Coolness is socially constructed (i.e., “a perception or an attribution bestowed by an audience”) (p. 544), which is similar to popularity or status

Coolness is subjective and dynamic: can use consensual assessment technique to measure (Amabile 1983), which is similar to creativity.

Coolness is a good thing (positive quality)

Coolness is more than positive perception or desirable

Cool is different from good (being liked) is inferred autonomy

Autonomy only increase perceptions of coolness under appropriate context

Coolness is ” a subjective and dynamic, socially constructed positive trait attributed to cultural objects (people, brands, products, trends, etc.) inferred to be appropriately autonomous.” (p. 544)

Autonomy increases coolness when it’s appropriate will depend on

whether a brand diverges from a descriptive or injunctive norm

the perceived legitimacy of the injunctive norm

th extent to which a brand diverges from injunctive and descriptive norms

the extent to which the observer or audience values autonomy

Descriptive norm is” what most people typically do in a particular context” (p. 545).

- People follow descriptive norm because of uncertain or unclear outcome, and the “normal” course of action is already effective. Hence, divergent could sometimes be more effective.

Injunctive norm is “a cultural ideal or a rule that people are expected to follow” (Cialdini, Reno, and Kallgren 1990)

- People follow injunctive norms because it can help build or maintain relationships or social esteem (p. 545)

Norm legitimacy moderates the appropriateness of divergence from an injunctive norm

Warren et al. (2019)

Conceptualizes “brand coolness” and a set of characteristics associated with cool brands

Cool brands are perceived to be extraordinary, aesthetically appealing, energetic, high status, rebellious, original, authentic, subcultural, iconic, and popular

Develops scale items to measure component of brand coolness and its effect on consumers’ attitudes toward brands, satisfaction, intention to talk about, and willing to pay.

Cool brands are dynamic and change over time.

Cool brands first to a small niche (subcultural, rebellious, authentic, and original)

Later, when adopted by the masses, cool brands acquire iconic and popular attributes.

8.3.4 Perceived Quality

(D. A. Aaker and Jacobson 1994) Brand quality influences shareholder wealth positively.

(Rebecca J. Slotegraaf and Inman 2004) Customer Equity, Satisfaction, and Quality: Role of Attribute Types Over Time

Research Context:

- The importance of understanding factors affecting satisfaction and quality, as highlighted by customer equity research.

Existing Literature Gap:

Prior studies recognized factors affecting satisfaction and quality.

Missed the potential for asymmetric effects over time based on attribute types.

Study Focus:

- Investigate how consumers’ perceptions of satisfaction with product attributes change as they near the end of the warranty period.

Attribute Classification:

Resolvable Attributes: Characteristics of a product that can be fixed or adjusted.

Irresolvable Attributes: Inherent characteristics of a product that can’t be changed or remedied.

Key Findings:

- As the warranty end approaches:

Satisfaction with resolvable attributes declines faster.

However, the influence of these attributes on overall product quality perception intensifies.

- On the contrary:

Satisfaction with irresolvable attributes decreases at a slower pace.

Their impact on overall product quality perception weakens over time.

(Kalra and Li 2008) Signaling Quality Through Specialization

Objective:

- To explore how firms, particularly in effort-intensive categories, can utilize specialization as a strategy to signal quality to consumers.

Premise:

- Companies often brand themselves as specialists, implying they’ve intentionally forgone alternative opportunities to focus on a specific area.

Methodology:

The study models a firm’s decision to either provide a single service or offer two services.

By opting for a single category, the firm sacrifices potential profit from the secondary category but might realize reduced costs.

This cost difference is termed the ‘signaling cost’ - the extra amount a high-quality firm might spend to differentiate itself from a lower-quality firm.

Key Findings:

Homogenous Markets: In markets with similar consumers, a firm of high quality signals its superiority by specializing in just one category.

Heterogeneous Markets: In varied markets, a firm can signal its high quality merely using its pricing strategy in both primary and secondary categories. But specialization still remains an effective, secondary quality signal due to its reduced signaling costs.

Role of Competition: The likelihood of using specialization as a signaling tool increases in competitive markets.

Implications:

Firms operating in effort-intensive markets can harness the strategy of specialization to convey their high-quality status to consumers.

While pricing can be a direct quality signal, specialization provides a subtle yet effective cue, especially in diverse markets or those with significant competition.

Businesses need to weigh the potential profits from diversification against the benefits of being perceived as a specialized, high-quality provider.