0.11 What does it mean to be in between?: The under-appreciated role of liminality

Evidence that being ‘between’ communities or systems was a factor affecting the ASHA’s role was found in all project data streams. In analysis of our extended qualitative discussions, ASHAs were found to be physically and conceptually ‘outside’ of the home even during visits to households as well as not being given a place to sit or a bathroom to use when at the local hospital assisting with a delivery (Chapter 4). Focus group discussions gave a clear impression of the Dai being within the home and the ASHA being more outside of it, which affects the behaviors she can influence and the points in time when she can deliver messages to a mother (Chapter 3). Quantitative analysis of the links between non-biomedical behaviors and influencers found that, in terms of what really affects what women do, that ASHAs are the closest and most-personal of medical influencers and the most-distant and least internal of community influencers; they are in between (Chapter 8 and Chapter 12). The liminal nature of the ASHA role, perpetually between household and health system but not fully a member of either, is in the description of the ASHA’s role as laid out in the NRHM and is also a key to the general rationale for CHW programs. However, the degree to which this creates unique tensions or is a critical factor affecting ASHA performance and motivation has been under-appreciated in evaluations of CHW programs.

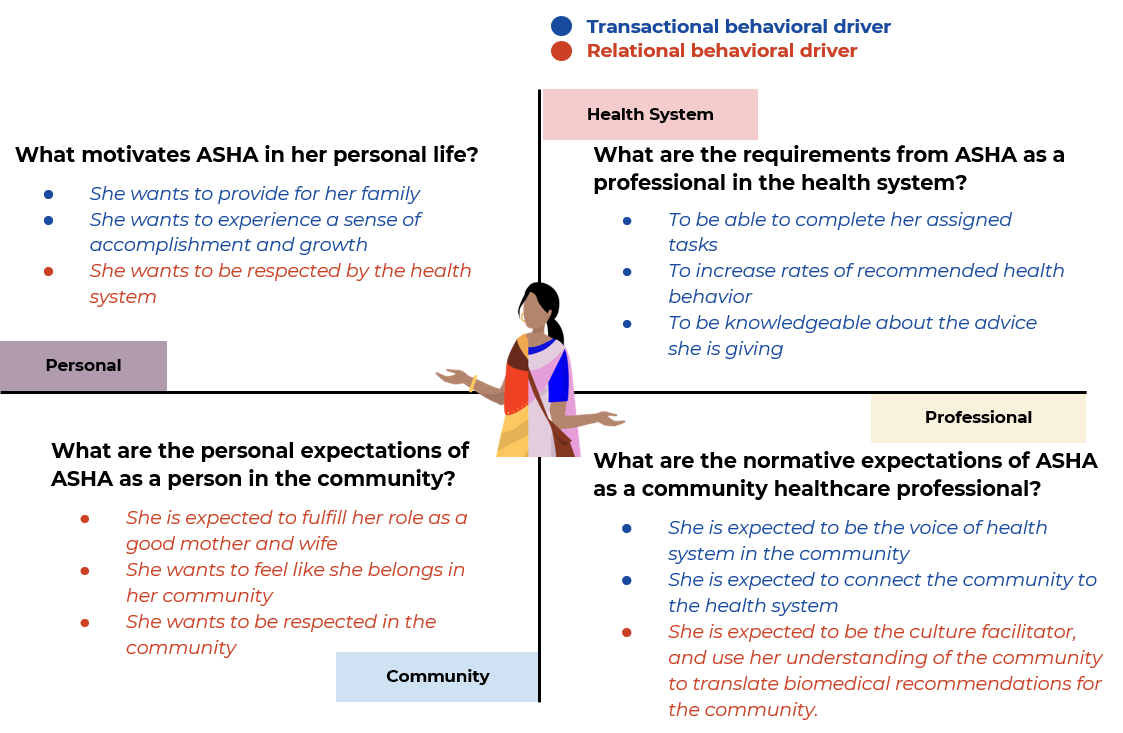

Indeed, the description of the ASHA’s role in the NRHM describes her as “interface between the community and the public health system.” We found evidence of her being an interface from many perspectives. The Project RISE co-design process took a closer look and found that being in this in between, liminal, state creates tensions for the ASHA that could potentially be ameliorated with the right kind of support or intervention-based tool. Figure 0.5 gives some of the issues that arise as a function of being a) a health worker who is embedded in the vary community within which she lives, and b) having the role of connecting community members to the health system. Each of these, a) and b), is an axis in the figure. This quadrant-approach became a valuable tool for mapping out tensions that arise from the ASHA’s role as a connector between worlds. Her professional life and her personal life both cross-cut the community where she lives and the health system that she’s responsible for connecting people to. There are many ways that personal and professional synergies and tensions can emerge from the ASHA’s role.

Figure 0.5: Motivations, expectations, and requirements of the four domains. The quadrant-based approach to viewing the ASHA role as composed of two axes. One that divides her life from personal to professional (she is a worker embedded in the community she lives in) and another that divides her life from community to health system (her role is to connect the community to the health system). This graphic gives some examples of the issues that arise in each part of the quadrant.

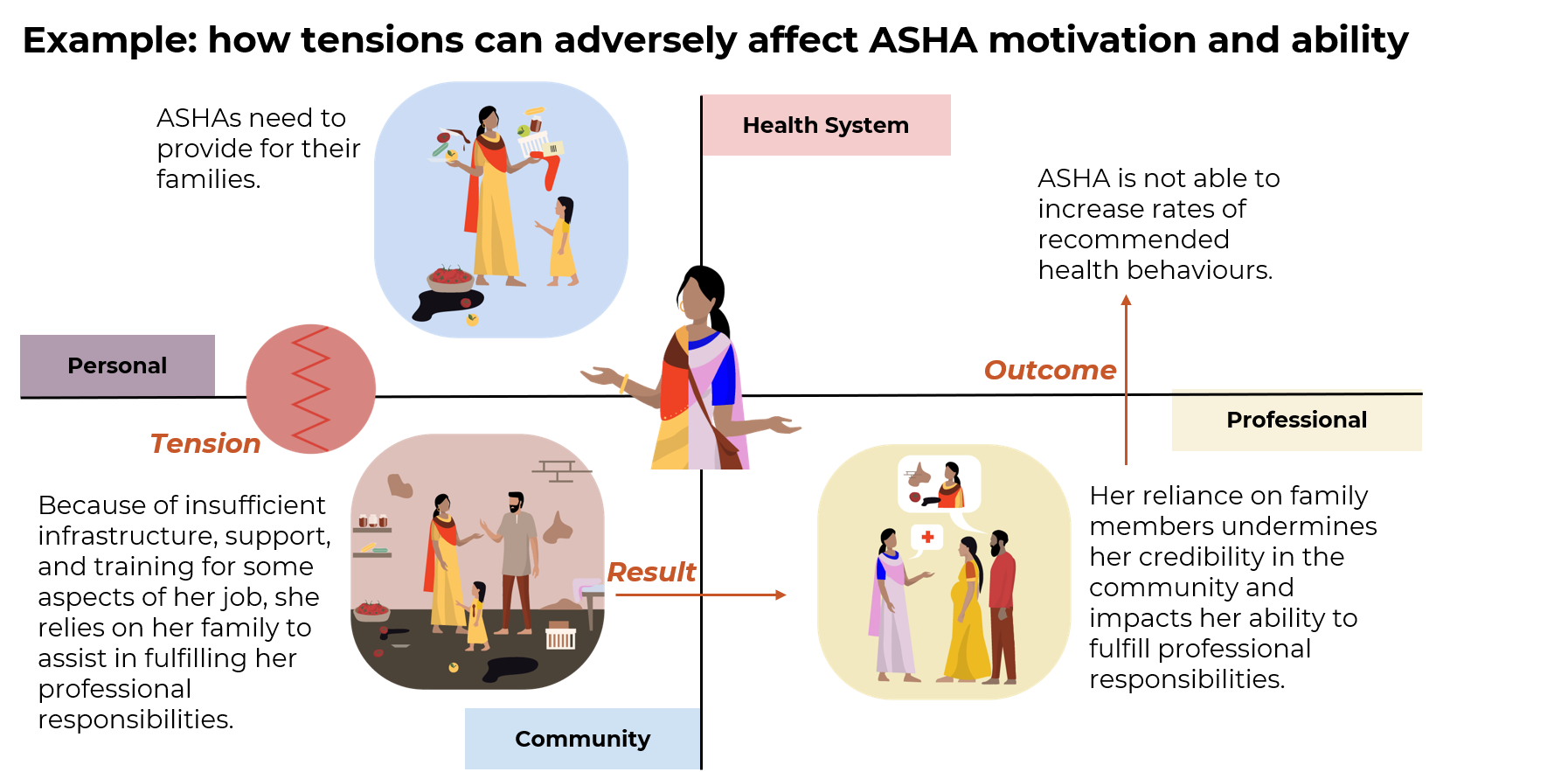

Some examples of how tensions can emerge due to the different expectations and requirements in each of these quadrants are presented in Figure 0.6. From our quantitative and qualitative work we found that ASHA’s want to be seen as competent successful mothers and leaders of a household. This can affect their motivation and also their standing in the community. The degree to which they can meet this challenge can be affected by how much support she gets from her family, MILs, older daughters, and husbands especially. Indeed, the ASHA’s desire to serve the community and provide for her household are interlinked and her ability to be a successful household leader likely affects her ability to be an effective persuader.

Indeed, many previous studies have found that ‘activist’ intended by the second A in ASHA is overshadowed or even blocked by her role as a connector or service extender (Fathima et al. 2015; Joshi and George 2012). These tensions between quadrants could be limiting the activist potential of her work (Figure 0.6). A cultural facilitator is a much more expansive and progressive notion for what a CHW can accomplish than that of a service extender. The ASHA could be a messenger that simply relays health information that is provided to her to an audience who is distant from the providers of the information. But she could also help persuade Mothers to engage in more healthy practices, or even communicate back to the health system what needs are not being met and what barriers to uptake might exist. Part of Project RISE’s final steps is imagining an ASHA 2.0 who is more equipped for persuasion and an activist role, in part because she is provided with tools to alleviate the under-appreciated tensions that emerge from being between community and health system and from having one’s work embedded within the community where one lives.

Figure 0.6: Understanding tensions can help make the shift from service extender to cultural facilitator.

The ASHA role was envisioned by the National Rural Health Mission to leverage her ties to the community and knowledge of local beliefs, practices, norms and needs in the community to act as a culture facilitator between the health system and the community.

The system also has yet to fully explore the ways in which her motivation and ability to perform a task at any point is shaped by the interactions between the expectations and requirements of her personal and professional roles across the health system and community and the resulting tensions.

In practice, the health system has limited its focus to the service extender aspect of her role, thus missing out on supporting and building the role of ASHA in engaging in culturally-sensitive health communication or strengthening her relationships and contacts with other stakeholders and CHWs in the community.

For example , ASHA trainings are based on providing biomedical information but not on how to navigate the social dynamic in the household, adapting messaging based on the motivations of the family and community and leveraging other health influencers in the community.