8.4 Results from ‘The Big Model’

The statistical analysis (see gray box in previous Section for details) quantifies the effect each influencer has on whether or not women in each sample actually do the behavior. We are differentiating between mentions and effects, where mentions are how often a particular influencer was verbally or conceptually associated with a behavior and effects are the probabilities of actually doing each behavior. In some cases the most-mentioned influencers also have the largest effects, but in other cases they do not and decoding this variation helps understand the pathways of decision-making that underlie maternal health behaviors in Bihar.

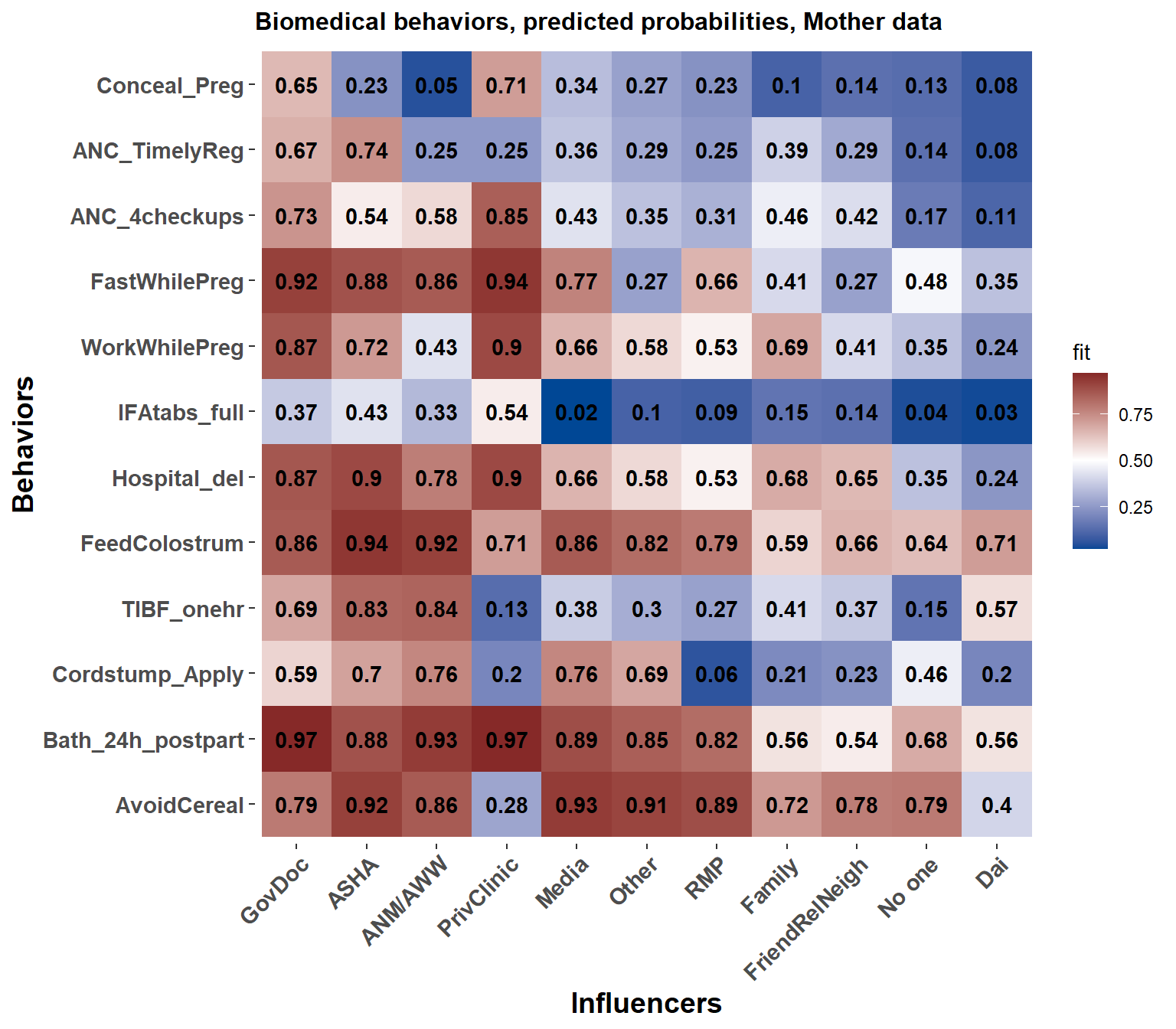

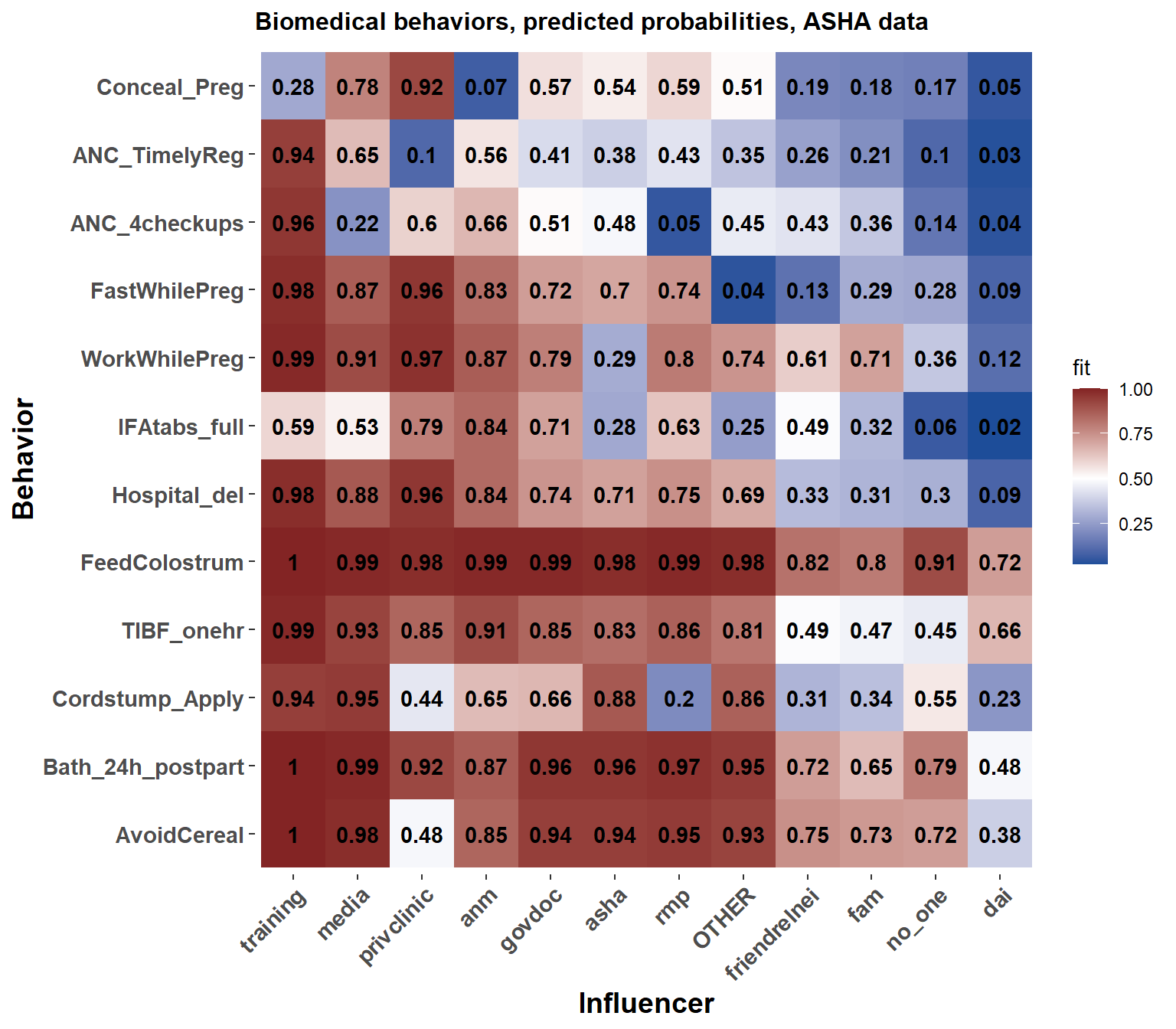

The results of this modeling effort are in Figure 8.4 for Mothers and Figure 8.5 for ASHAs. In these figures we examine only the biomedical behaviors and the neutral behaviors will be treated in a separate analysis. For each behavior the probability is of doing the biomedical recommendation. This means that the figure reports the probability that participants do: register for ANC in first three months, have a hospital delivery, initiate breast feeding within the first hour (TIBF), and feed colostrum and the probability that participants do not: conceal the pregnancy, fast while pregnant, work while pregnant, apply substances to the cordstump, avoid eating cereal after delivery, or give the newborn a bath within 24 hours of birth.

In the Mother data we see separation on the x-axis of biomedical experts on the left and normative or non-medical sources of influence on the right. In some cases the gradient across influencers is really striking. For instance, if the ASHA or government doctor is the primary source of influence then the probability of feeding colostrum is over 90%, but is under 40% for influence from an RMP. Dais have a positive effect on feeding colostrum and TIBF but negative effects on many other behaviors.

8.4.1 Biomedical Behaviors

Figure 8.4: Each influencer's effect on the probability that Mothers respond according to biomedical recommendations for each behavior.

For the ASHAs we see some striking differences in the influencer to behavior landscape. Some of this could be due to recall bias (as the births were less recent) and some could be due to desirability bias (as the ASHAs will generally know what the ‘correct’ response is for each question). Training is always strongly associated with the direction of biomedically recommended behaviors. Among ASHAs family and friends/relatives/neighbors are further to the right of the figure indicating that these groups are more strongly associated with not following biomedical advice among ASHAs than Mothers.

Figure 8.5: Each influencer's effect on the probability that ASHAs respond according to biomedical recommendations for each behavior.

8.4.2 Neutral Behaviors

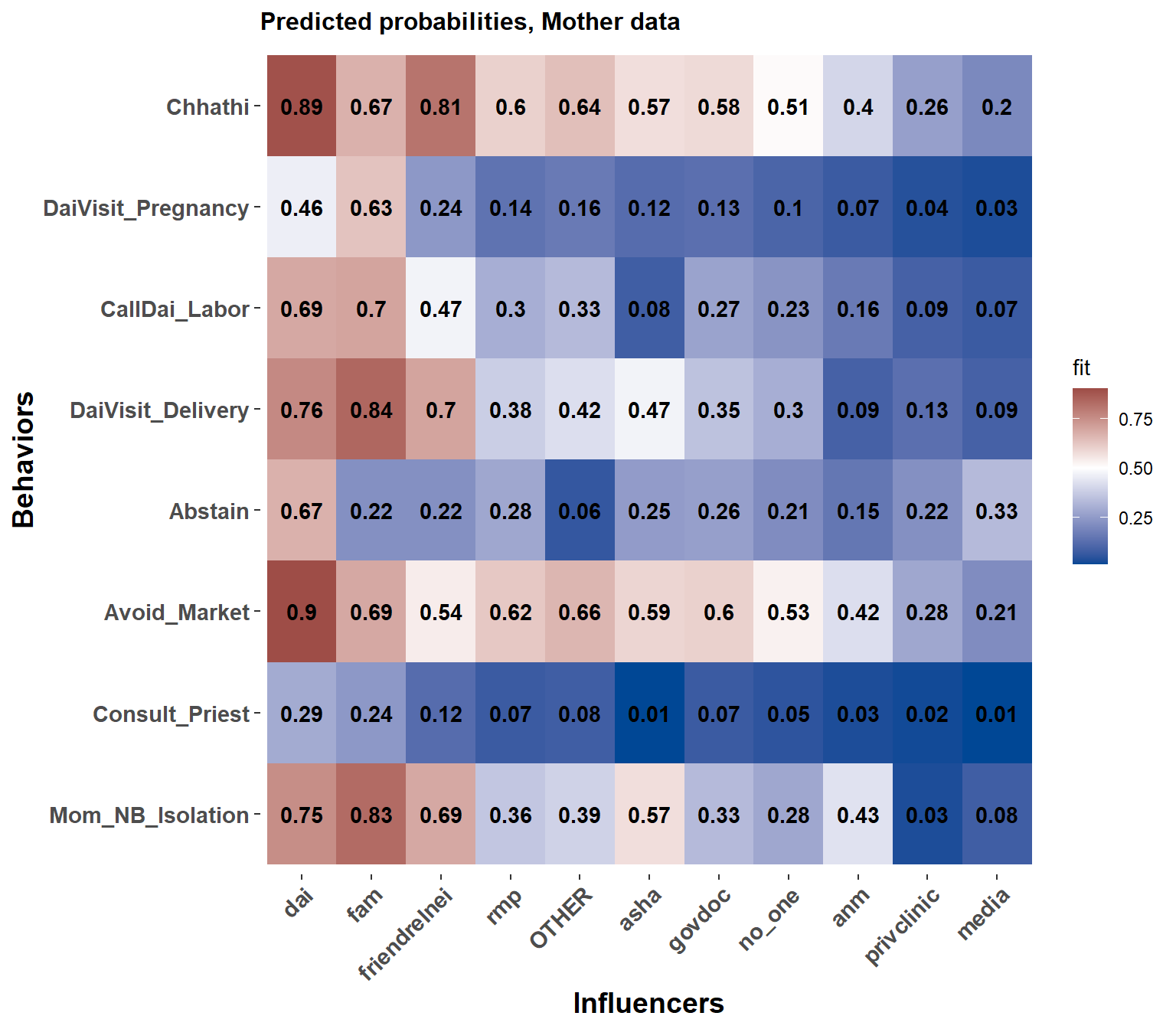

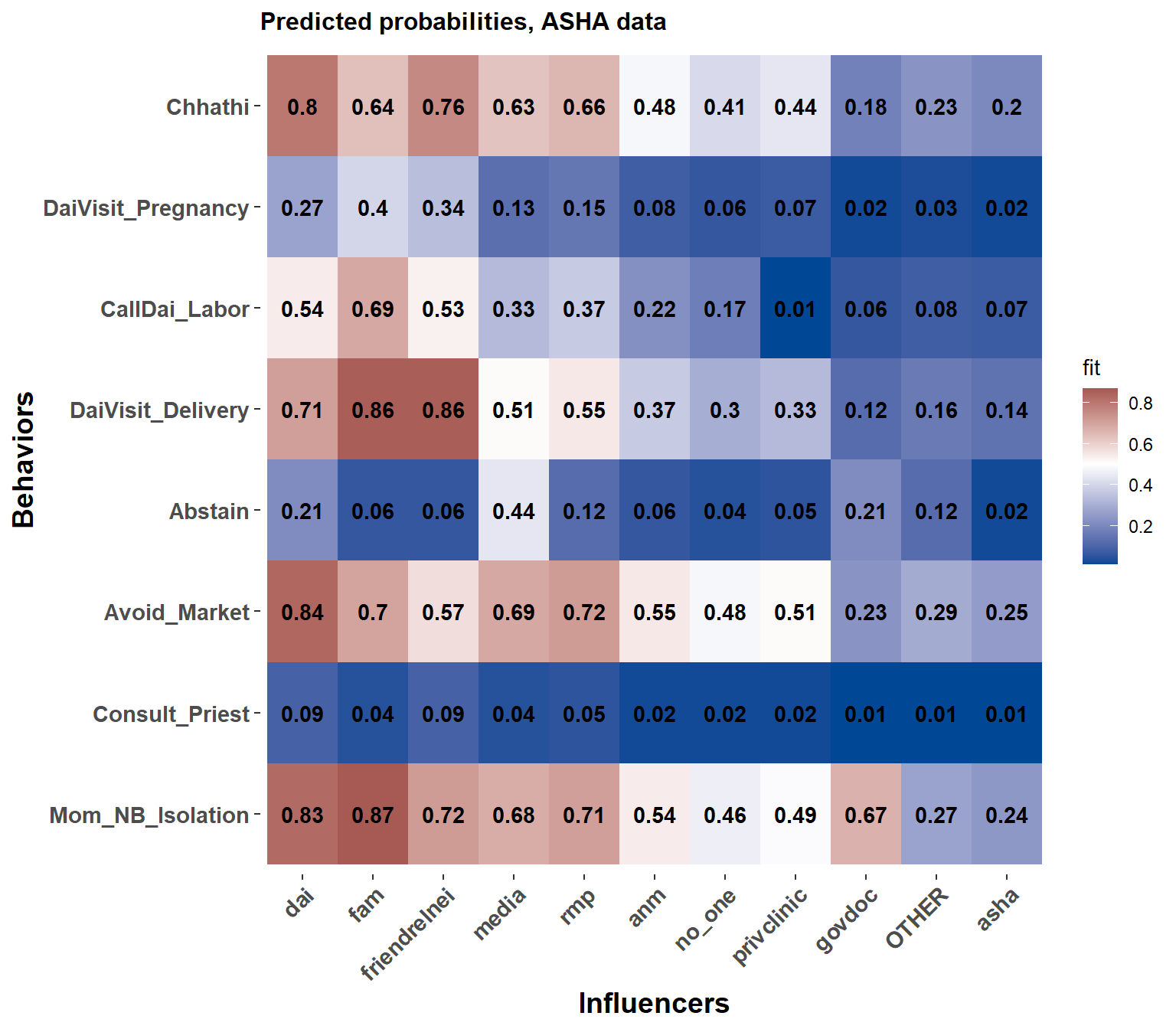

Several of the behaviors are considered neutral from a biomedical perspective. These were modeled separately because there is a slightly different meaning to the ‘yes’ and ‘no’ responses for questions that do not have a specifically mandated health-enhancing response. Also, because the models include interactions, we didn’t want to add the complexity of interpreting how an influencer affected a health behavior, controlling for their interactions with neutral behaviors, or vice versa.

Otherwise, we mirror the process of presentation done for the biomedical behaviors.

Figure 8.6: Each influencer's effect on the probability of saying yes to each behavior, mother data

Figure 8.7: Each influencer's effect on the probability of saying yes to each behavior, ASHA data

In the ASHA data we see the strong and consistent presence of the Dai. Also, all the medically oriented or external sources of influence are to the right of no one.

8.4.3 Neutral Behaviors and being in between

In Figure 8.6), we see that for Mothers the ASHA is often next to no_one in terms of influence. Moreover, her positioning is to the right of influencers related to community norms, family, and ‘inside the household’ and to the left of biomedical and external influencers. This central position is again indicative of the ASHA’s betweenness.

By contrast, the Dai has a strong positive influence on the probability that women ‘do’ all of the neutral behaviors.