12.6 Tensions and Liminality

The ASHA is in a liminal state by design, therefore it is incumbent on the designers of the ASHA program to equip ASHAs with the tools to manage tensions that result from the unique features of their role. Most studies of ways to improve ASHA performance focus on service delivery or knowledge gaps, rather than on ways to empower ASHAs, to help them be better persuaders (cultural facilitators),

The India Government’s National Rural Health Mission (NRHM) describes the ASHA role as “the interface between the community and the public health system.” Both the focus group discussions and ethnography documented several instances that speak to ASHA as a connector, or as one positioned between systems. Throughout this report we have documented qualitative and quantitative evidence that establishes liminality as a key factor affecting ASHA dynamics. We suggest that ASHAs are embedded health workers who are constantly in a liminal state between their communities and the formal government health system. Unique tensions emerge from being in a liminal state and these need more exploration from the perspective of improving performance and motivation.

Health facility staff tend to perceive ASHA as an intermediary, and not necessarily as an extension of health system in the community. By the communities, ASHAs are perceived as someone who does not have a role in service delivery beyond bringing the community to a service touchpoint. This establishes an unequal power dynamic that manifests in the facility staff exhibiting behaviors such as demanding bribes, and treating her disrespectfully. ASHAs reported experiencing disrespectful behavior when making requests from the health providers with regards to their payment. This kind of treatment at the facility leads to a loss of face for the ASHA in the community, where it is imperative that people take her seriously, for her to accomplish the tasks that are set out for her.

In practice, the health system has limited its focus to the service extender aspect of her role, thus missing out on supporting and building the role of ASHA in engaging in culturally-sensitive health communication or strengthening her relationships and contacts with other stakeholders and CHWs in the community. For example, ASHA trainings are based on providing biomedical information but not on how to navigate the social dynamic in the household, adapting messaging based on the motivations of the family and community and leveraging other health influencers in the community.

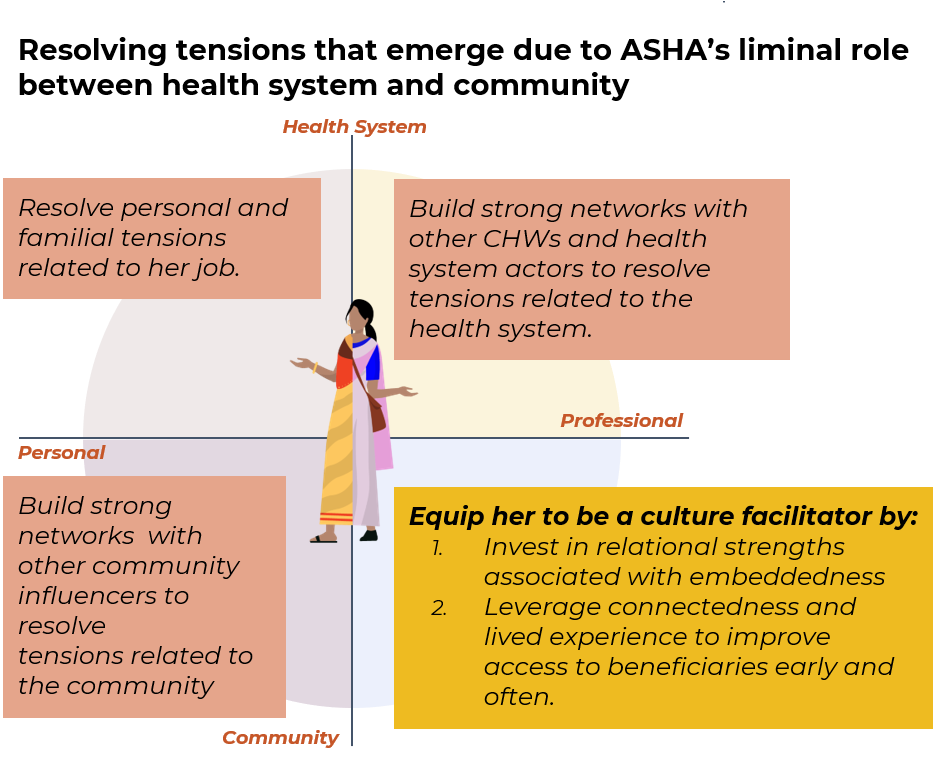

Figure 12.7 shows a conceptual scheme informed by Project RISE data for some ways to ease tensions that emerge from the liminality experienced by ASHAs. Tensions can occur in each of the main quadrants formed by being between health system and community and between her lived-experience and her professional role. We see resolving these tensions as an essential part of facilitating a transition from service extender to cultural facilitator.

Figure 12.7: Develop a general approach for resolving tensions from liminality that might emerge in each quadrant.

Multiple project RISE datastreams suggested that ASHAs are motivated by both the desire to serve their communities and to obtain additional income for their families. The paperwork and red tape to get the payments is cumbersome and a major source of complaint for the job, and those payments come with a lot of uncertainty in terms of actual amounts and timing. ASHA motivation clearly consists of both extrinsic and intrinsic motivations, but desires to improve ASHA performance (or to evaluate it) may be missing out if they do not include ways to document the role of intrinsic motivation. The payment systems really highlight some of the tensions the ASHA experiences. The payments create a tension of their own and yet the fact that the ASHAs get some payment at least occasionally undermines trust with the community, a finding that was particularly evident in our vignettes (Chapter 9).

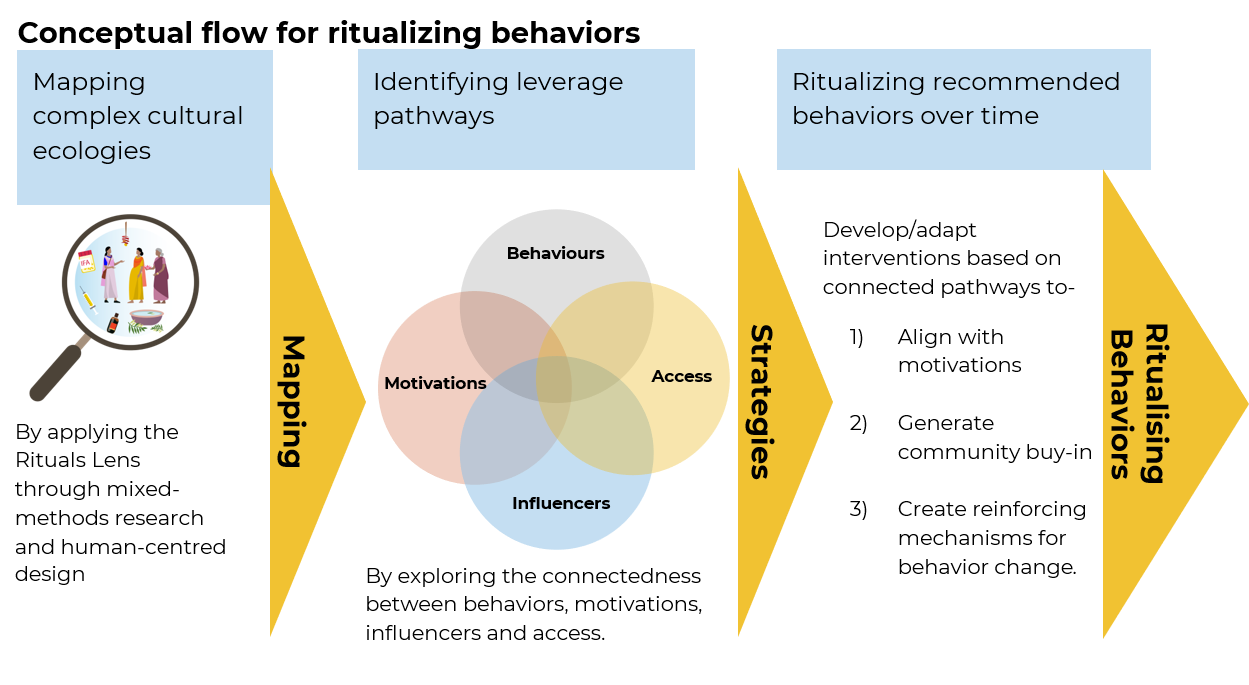

The co-design process, carried out in abbreviated form via WhatsApp due to the Covid-19 pandemic (Chapter 10), applied a general framework for applying a ritual lens to the kinds of complex cultural ecologies of health that the ASHA operates within (Figure 12.8). In the Figure, we move from mapping out the factors that affect behavior change, and that should be accounted for in evaluation and/or design. From that, four pathways emerged: motivations, access, behaviors, and influencers.

motivations: ASHA embeddedness raises unique tensions that affect her motivation and performance.

access: ASHA interactions are impactful but access is missing during critical time periods.

behaviors: The perinatal journey is shaped by complex inter-connections of behaviors and motivations.

influencers: ASHAs are the primary influencer for some behaviors, and only one among many for others.

Third, to the right panel of the Figure, develop interventions based on connected pathways to align with ASHA motivations, that generate community buy-in, and that create reinforcing mechanisms of behavior change.

Figure 12.8: The beginnings of a framework to help resolve the unique tensions that emerge as a function of being in a liminal role between health system and community.

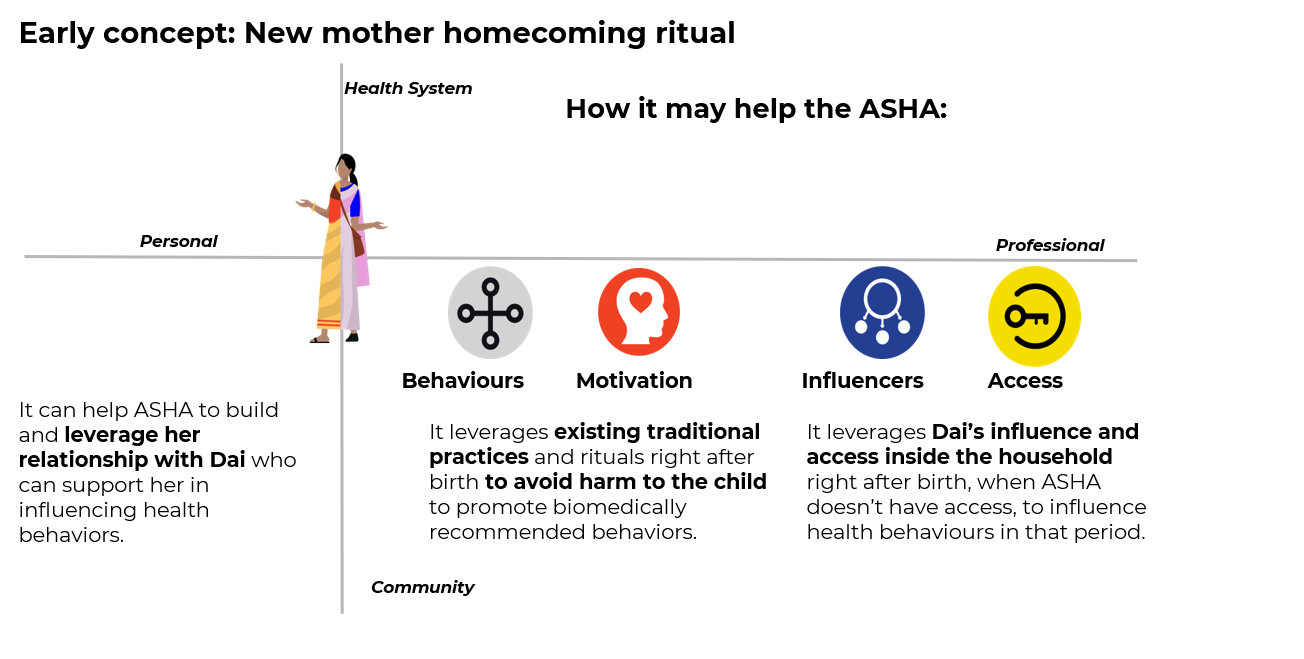

The co-design process also made two suggestions for ways that ritual could help alleviate the tensions ASHAs experience due to liminality. The first is a ‘homecoming ritual’ that involves the Dai, ASHA, and family (Figure 12.9). This addresses an area of high concern, and high potential impact, as the first few days at home just after birth. It helps achieve complimentarity across belief systems by bringing together ASHA, Dai, and Family.

Figure 12.9: Creating a new homecoming ritual involving the Dai and family after delivery to promote biomedically recommended behaviors and avoid harmful ones.

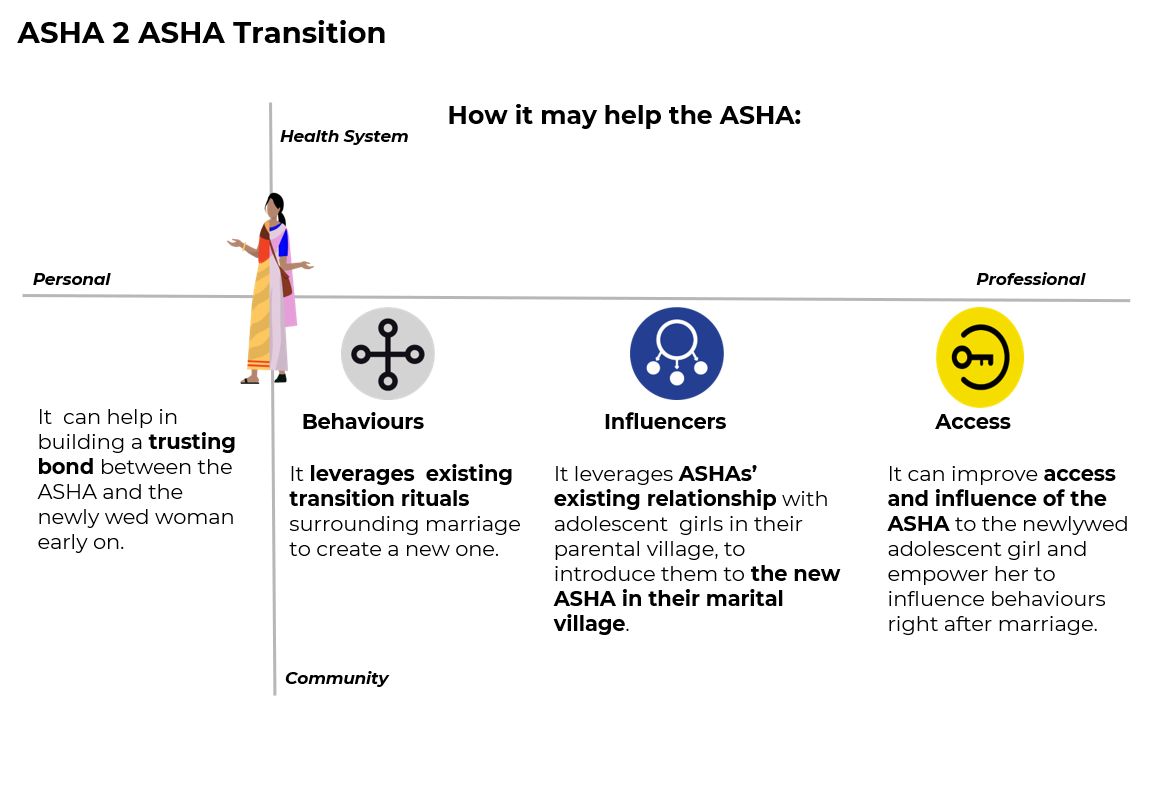

The second example ritual from co-design is an ASHA-to-ASHA handoff ceremony. This ensures that the ASHA and new mother have a strong relationship both in the village of her husband and when she returns home to her mother’s household for delivery. Facilitating a stronger bond across ASHAs can also give them more opportunity to exchange information and resources.

Figure 12.10: Creating a new ritual where ASHAs in parental home connect engaged young women to the new ASHAs in their in-law’s village.