12.3 Liminality and the Foundation of the ASHA Program

12.3.1 ASHA is a connector between systems

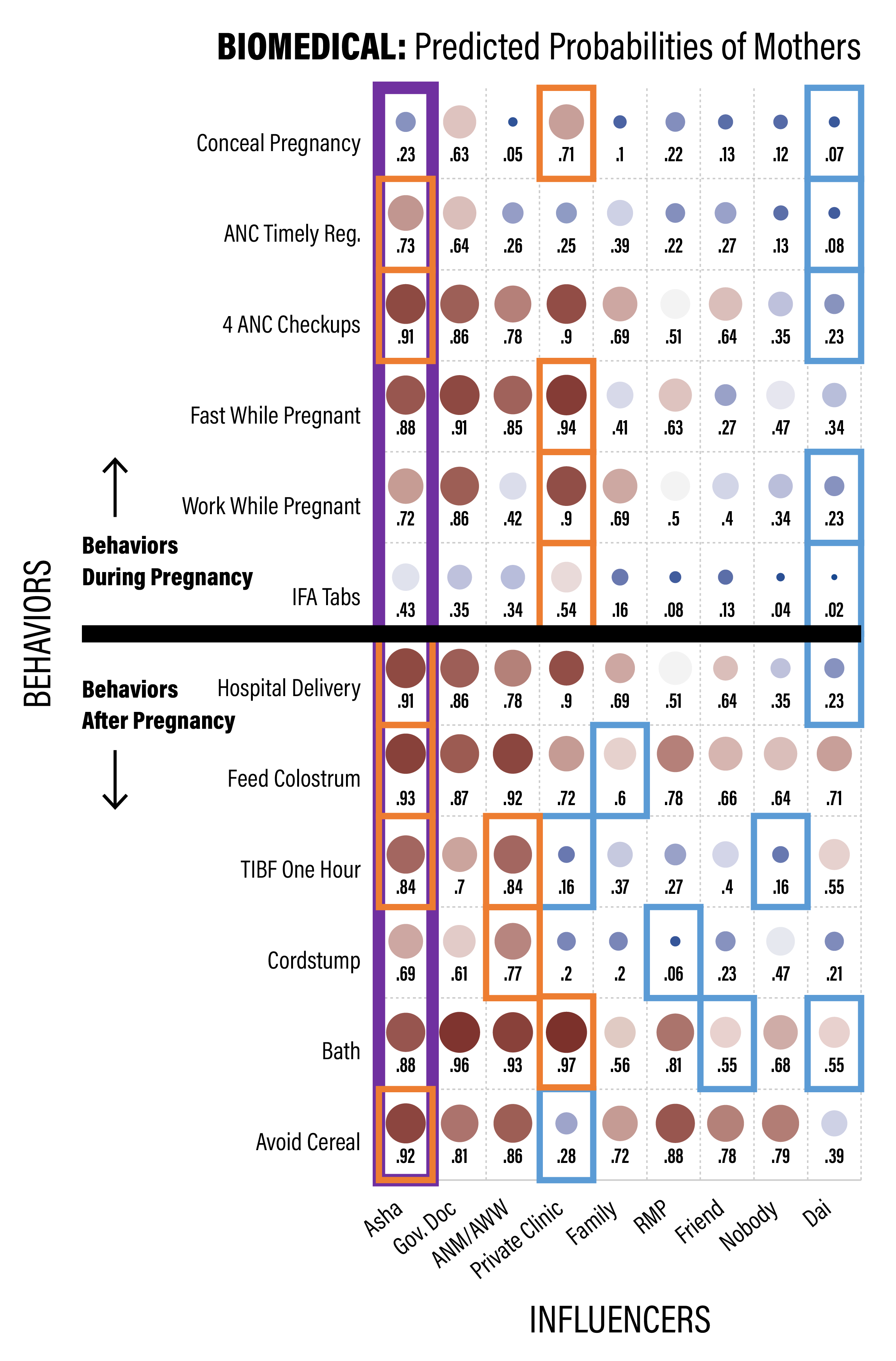

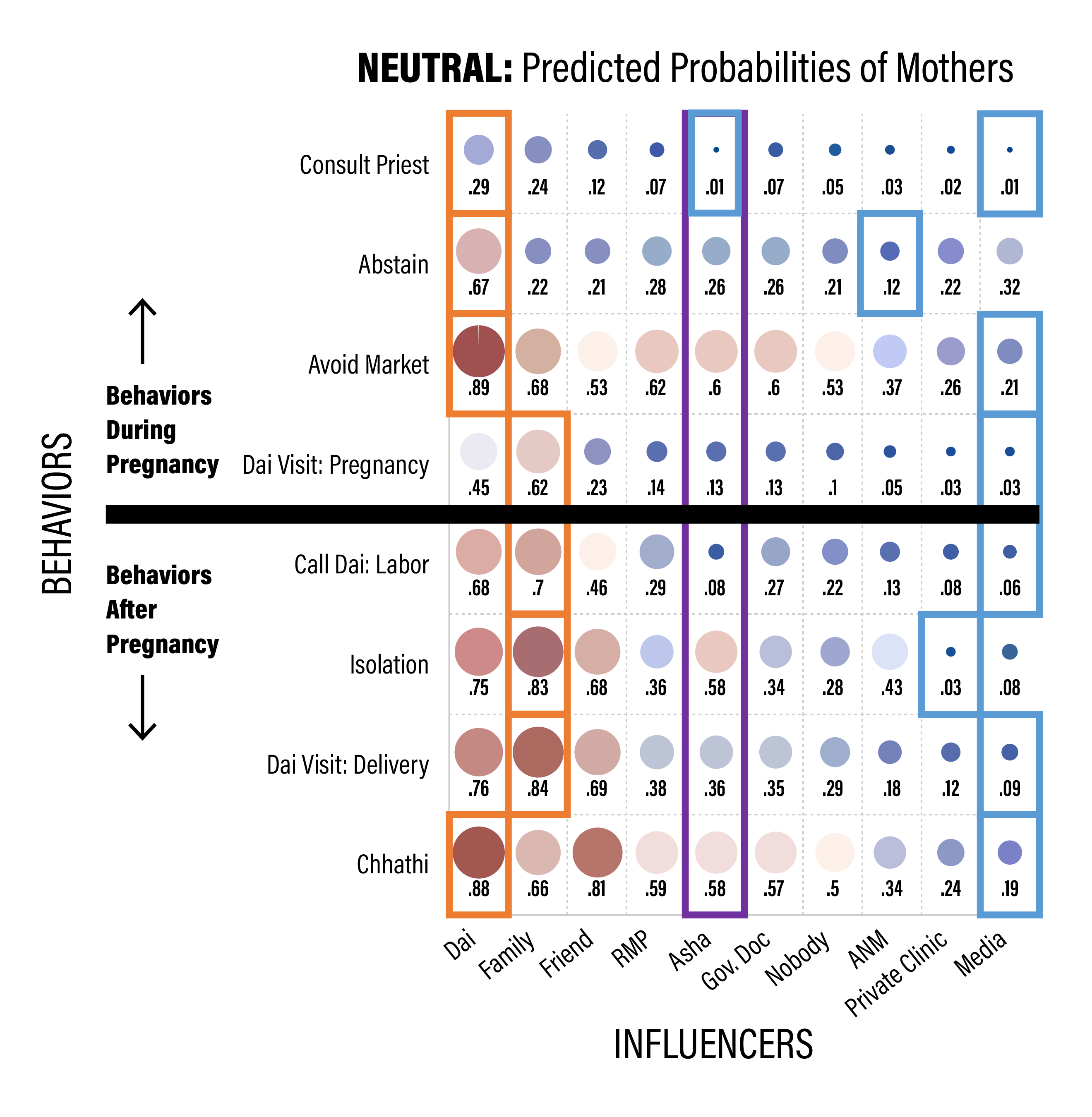

The next two figures illustrate the nature of ASHA’s positioning via her influence on (and cognitive association with) a number of behaviors (details in Chapter 8). While the figures contain a lot of information, a rather nuanced picture emerges when comparing them.

Figure 12.2 shows ASHA positioning with respect to biomedically relevant behaviors and Figure 12.3 shows ASHA positioning with respect to neutral behaviors.

In both cases, the influencers associated with high probabilities of doing the behavior are to the left and influencers associated with low probabilities of doing the behavior are to the right. The largest value in each row marks the influencer with the largest statistical effect on that behavior and is outlined in orange. The lowest value in each row, and hence the lowest statistical effect on doing the behavior, is outlined in blue.

For the biomedical behaviors (Figure 12.2), we see that the ASHA is always to the left, high influence part of the Figure. She often has the highest positive influence (orange squares) and in that sense is within the medical system by strength of impact. Sources of influence that we might think of as being closer or more personal to mothers are always to the right, indicating lower statistical influence. The influencer categories of friends/relatives/neighbors, family, the RMP, the category of ‘no one,’ and the Dai are all mostly the negative or lowest influencers for biomedically-relevant behaviors.

For the neutral behaviors (Figure 12.3), we see that the ASHA is in the middle, positioned between medical influencers and personal or household influencers. This indicates her liminal role. On these more traditional and household-oriented behaviors, ASHA tend to be more influential than any influence associated with the medical system and less influential than family, friends, relatives, or the Dai. She is a connector in a liminal state. We argue that her role as an ASHA is part of her liminality. The ASHA tends to lower the probability that Mothers call a Dai for delivery.

The ASHA and Dai possibly compete a little over services related to delivery. Both receive incentives and there has been a large shift in time away from home delivery (Dai’s domain) and toward institutional delivery (ASHA’s domain). In the focus group discussions (Chapter 3), some participants remarked on the reduced role of the Dai and even tied reduced services and income to the ASHA program. However, we did not find any evidence for overt conflict or resentment between ASHA and Dai. Indeed, ASHAs report appreciating some Dai services, such as massages given to mother and newborn.

Figure 12.2: ASHA positioning as an influencer of biomedical behaviors for recent mothers. The red squares toward the left are around the largest value for each row, indicating the strongest positive influencer for that behavior, and the blue squares are for the lowest value for each row, indicating the lowest influencer for that behavior.

Figure 12.3: ASHA positioning as an influencer of neutral behaviors for recent mothers. The red squares toward the left are around the largest value for each row, indicating the strongest positive influencer for that behavior, and the blue squares are for the lowest value for each row, indicating the lowest influencer for that behavior.

12.3.1.1 ASHAs and Dais are associated with different behaviors

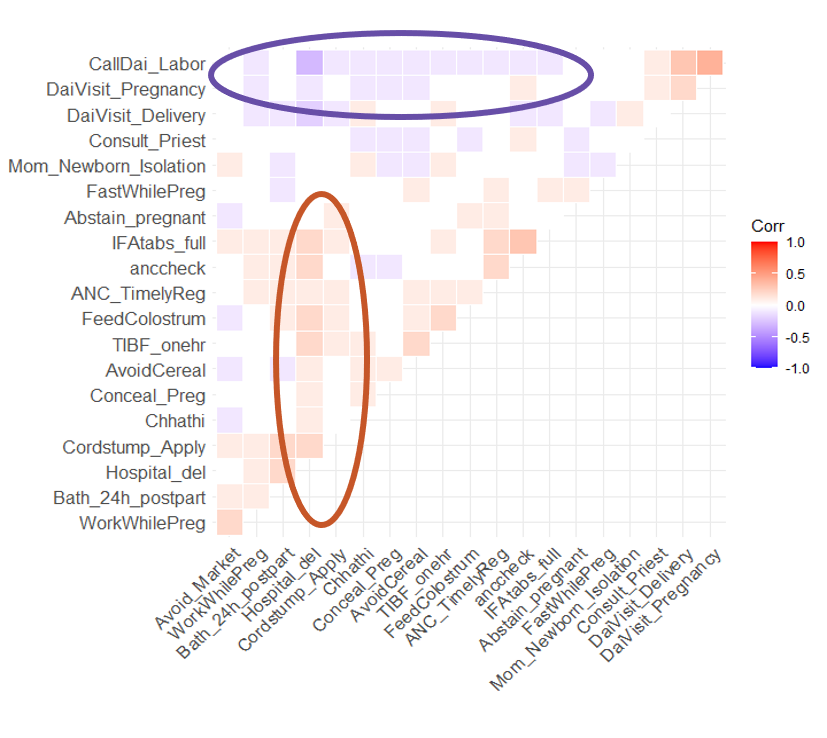

One key RISE theme is that behaviors don’t exist in isolation, but rather are connected to one another via complex constellations of belief and influence. In Figure 12.4 we show a simple correlogram that arranges all 20 focal behaviors according to correlations among responses. Colors that are reddish indicate positive associations such that being more likely to do the recommended response in one is more likely to do the recommended response in another, for biomedical behaviors (or simply to report ‘yes’ to the traditional or neutral behaviors). Likewise, the blue-ish squares indicate being more likely to do the recommended behavior for one makes one less likely to do the recommended behavior of the other, or simply to report ‘no’ to traditional or neutral behaviors.

The upper cluster of blue-ish squares indicates a cluster of behaviors that seem largely correlated with calling the Dai for Labor. Unfortunately, some non-recommended behaviors cascade together and seem associated with Dai interactions. The lower vertical reddish cluster shows behaviors clustered with institutional delivery and others strongly associated with the ASHA.

Figure 12.4: Behaviors vary and form clusters with different influence. Understanding behavioral connectedness has implications for understanding most efficacious target(s) of intervention.

In other parts of the report we take an in depth look at these behaviors and what sources influence decisions mothers make about which ones to take up (e.g., Section 8.6). These correlations reveal several ways in which behaviors are linked together, in this case by patterns of adoption. It also shows that one of the strongest positive correlations is between getting 4 or more ANC checkups, which occur outside of the home, and taking the full regimen of IFA tablets.

The connectedness of behaviors can create challenges and complexities for evaluations of ASHA performance that only focus on particular outcomes. Likewise, interventions may need to think more broadly, and aim toward constellations of behaviors.

12.3.1.2 ASHAs and Dais influence a different set of behaviors

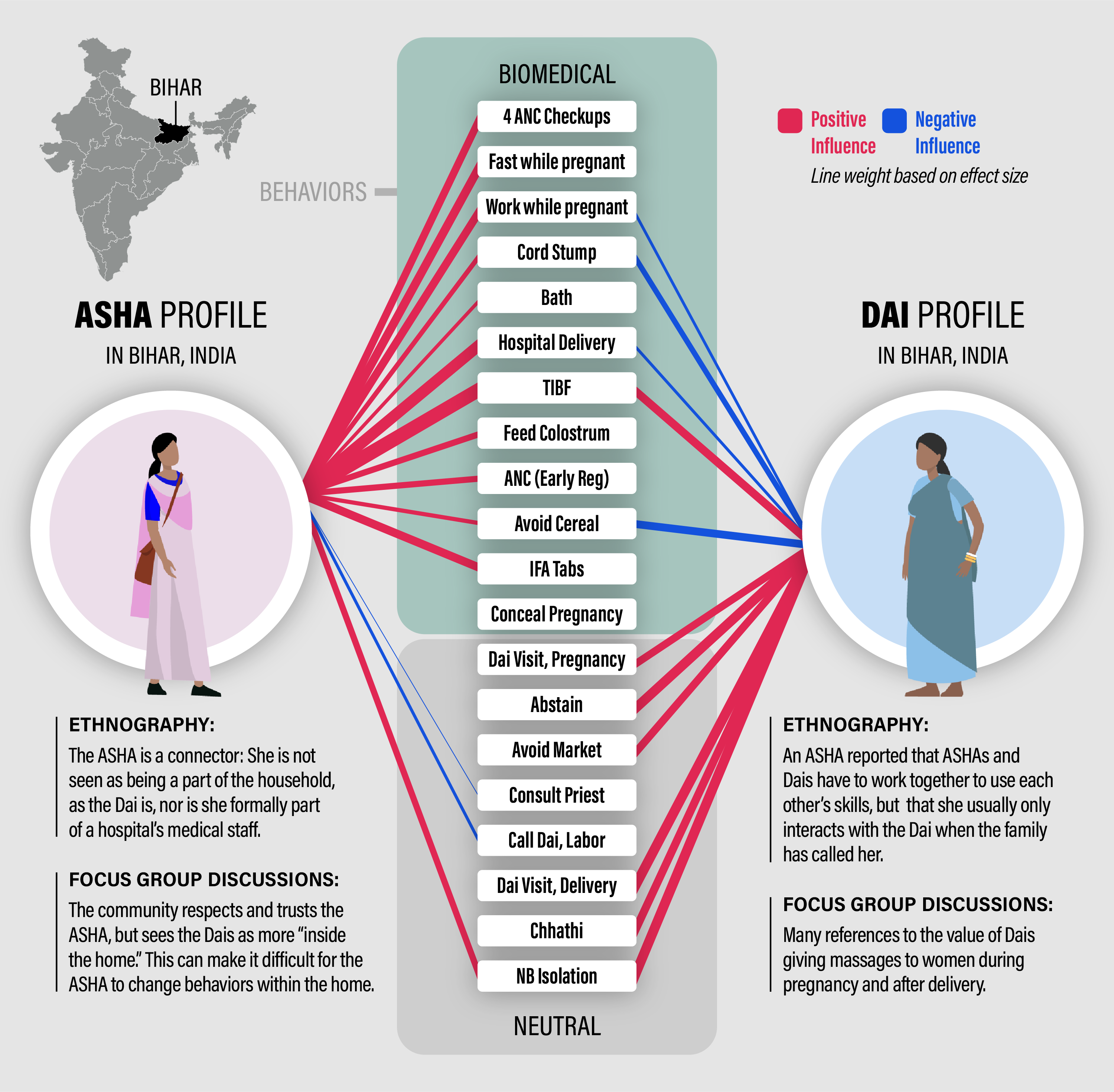

A somewhat pivotal moment in the synthesis of Project data arrived when we decided to take a closer look at differences in similarities between the ASHA and Dai, particularly with regard to which behaviors they affect and how. This was motivated by two factors, one practical and the other empirical. Practically, across so many observations in multiple data streams, one needs to develop ways to simplify a very complex picture. Comparing two influencers, as opposed to ~10 simultaneously, is one way to do that. Empirically, there were many reports in the FGDs and the ethnography that contrasted the role and positioning of the ASHA and Dai in ways that suggested some illuminating relationships could emerge by comparing them more carefully. For instance, results from the FGDs implied that the community respects and trusts the ASHA, but sees the Dais as more “inside the home,” which indicated a possible barrier to the ASHA. Similarly, the ethnography observed that in her role as a connector, the ASHA is not seen as part of the household, as the Dai is, nor is she formally a part of a hospital’s medical staff; she is in-between, or in a liminal state. These observations further indicated that at times ASHAs simply lack access at times when messaging is crucial.

Figure 12.5: ASHA - Dai comparrison: The red lines represent positive effects on the probability that women do the recommended biomedical behavior or do the neutral behavior. Blue lines represent negative effects. The effect is relative to the reference category of no one. The line thicknesses are scaled to the magnitude of the effect. Only effects that have non-overlapping confidence intervals with no one are drawn.

The results of some of our ASHA-Dai comparisons are in Figure 12.5. It is immediately clear that ASHA - Dai differences were captured in the quantitative data and reveal distinct patterns of influence consistent with the qualitative suggestions that ASHAs were more ‘outside the home.’

Figure 12.5 contains a lot of information. First, the center column is each of the 20 behaviors that are extensively covered in Chapter 8, with the 12 biomedical behaviors on top and the 8 neutral ones below. Importantly, recall that the biomedical behaviors include those that are recommended and not recommended but we model the response as doing what is consistent with biomedical recommendations. The neutral behaviors are not associated with recommendations and hence are just “yes” for did the behavior or “no” for did not.

The ASHA is on the left of this column of behaviors and the Dai is on the right. The red lines indicate positive influences on the probability that the response was ‘yes’ relative to the reference category of ‘no one’ (see 8.6 for more information). Blue lines indicate that the influencer lowers the probability that the answer was ‘yes.’ The thickness of the line is scaled for how different the influencer was from no one, so a thicker line means they have a much larger, if red, or much smaller, if blue, effect compared to no one. No one is a useful reference because it is the one option on the influencer part of the survey not directly equated with a specific source of influence. When an individual does not readily associate a behavior with an influence she likely selects “no one,” indicating a received normative inclination.

Scanning down the central column from top to bottom, we see that the ASHA has a positive effect on every biomedically recommended behavior, except for one - concealing pregnancy. In contrast, most of these are not affected by the Dai, except for four that the Dai affects negatively and one that the affects positively.

In contrast, when we scan down the neutral behaviors, most of which are traditional in nature, we have almost the reverse impression: the Dai positively influences all but one and the ASHA influences very few and more of them negative than positive. Hence, the ASHA’s influence is universally ‘positive,’ inline with biomedical advice, for the biomedical behaviors and absent or spotty for neutral ones.

Moreover, we can look at behaviors that are influenced by both, ASHA and Dai, and place them into two categories: aligned or conflicting:

Aligned behaviors include timely initiation of breastfeeding (TIBF) and mother - newborn postpartum isolation, both of which are behaviors just after delivery. Alignment between the Dai and ASHA on TIBF, an important health-outcome, is a good sign, suggesting some potential for further leveraging this relationship. Mother-newborn isolation is coded as ‘neutral’ but there are functional and traditional benefits to this behavior. It helps ensure a clean and safe place for the mother and newborn to rest and recuperate from the birth. It keeps them away from visitors and other inadvertent vectors for bacteria. It includes an assigned family member to act as a primary caretaker.

Conflicting behaviors include working while pregnant (ASHA positive, Dai negative), treating the cord stump (ASHA positive, Dai negative), hospital delivery (ASHA positive, Dai negative), avoiding cereal postpartum (ASHA positive, Dai negative). Treating the cord stump and institutional delivery are both target behaviors often emphasized in health initiatives. Cord stump treatment is likely part of the traditional set of services, many relating to massage, associated with the Dai. The complementarity example, mentioned above, could be used to lower the frequency of cord stump treatment. This is one of many reasons why a strong relationship between Dai and ASHA could be important.

Across these connections we see strong support for the impressions gleaned from FGDs and ethnography, that there are some parts of a Mother’s perinatal journey when an ASHA has limited access. We also suggest that the Dai should not be framed as a negative influence on health behaviors. Dais perform many valuable tasks, appreciated and valued by Mother and ASHA. The discussion of ritual, above, pointed out the importance of complementarity in ritual. A similar concept could apply here. The ASHA and Dai are aligned in motivation and share common ground. The commonality should be leveraged to reduce the associations between traditional or Dai-connected inputs and biomedically-non-recommended behaviors (such as those seen in Figure 12.4. In short, the behavior change community shouldn’t criticize Dai but rather find ways to leverage that relationship to extend ASHA reach.