8.6 The Perinatal Journey by 1000 (38) Bar Graphs

To meet the goals of Project RISE we studied a series of perinatal behaviors that were coded into three categories, not-recommended, recommended, and neutral (overviews of these behaviors are in Chapter 7 and a statistical model analyzing what affects uptake of these behaviors was presented above). These behaviors occur at various points in the perinatal journey, from early pregnancy to post-partum. Here we use the output of the modeling endeavor to look at the suite of analyzed behaviors, biomedical and neutral together, in an approximately sequential fashion across the perinatal period.

A key aspect of Project RISE is understanding the connectedness of behaviors and how beliefs and narratives about those behaviors can have inputs from several sources, hence the emphasis on influencers. Likewise, a key feature of the modeling approach summarized in the previous section is that we can quantify the effect of sources of influence relative to others.

With the graphs above, we have calculated probabilities for each behavior given input from each influencer. These graphs do not tell us which influencers are having relatively large positive or negative effects relative to some expectation or common reference. The graphs below allow us to make statistically sound inferences about which influencers are the most critical, or most impactful, for each behavior. A natural reference value for such inferences was included in the option sets in the survey used to collect these data. One of the choices women can select is ‘no one’ as a source of influence. Here we examine which influencers are more, or less, influential than no one.

In reading the following set of bar graphs note the following:

one of the influencer categories is ‘no one,’ meaning that there is no clear influence and the person ‘just did it’ (which we might equate with a passively received normative expectation, but it could be other things too). This category of ‘no one’ is a useful reference category and when we are inferring important positive influences (in red) or important negative influences (in blue), we are doing so relative to the category of ‘no one told me to do it.’

in each of the following graphs a horizontal dotted line is drawn at the effect of no one for that behavior. If our estimates for the effect of an influencer are non-overlapping with the estimate for no one, we shade it red if it is more positive or blue if it is more negative.

these are a lot of graphs to take in but they are organized temporally and we intentionally place neutral and biomedical behaviors close together to show the multitude of factors that are being reasoned about and negotiated and via what other agents as a woman moves through this journey.

we have 19 behaviors and two data sets. One data set is on Mothers and the other is on ASHAs where they report their behavior from their most recent birth. Part of the Project RISE philosophy is that to examine motivation and performance through a ritual lens we need to understand the lived experience of the ASHA and how it compares with the women she is assisting and perhaps attempting to persuade to adopt new behaviors. This allows us to understand her experience and what aspects of it are most similar to the beneficiary community, the Mothers.

when differences between Mothers and ASHAs are observed, without further analysis we can’t say for sure if this is due to a generational/age difference (ASHAs are on average older than the beneficiaries and the time to their most recent birth is on average longer), or due to the training that ASHAs receive to become ASHAs, or to some other factor such as ASHAs being on average a little more educated and from different castes. However, when there is no difference between ASHAs and Mothers we know that the behavior may be resistant to a variety of these factors and certainly did not change due to training or age.

each graph displays the sample sizes for each option at the bottom of each bar in the bar graph. NOTE: those with less than 5 observations were excluded in order to minimize cluttering of the figures and we wanted there to be some reasonable degree of salience in terms of how often an influencer was associated with a behavior. Importantly, these are the actual sample sizes we are reporting, not percentages, so please recall that there are 1200 women in the Mothers sample and 400 ASHAs and that women can select multiple influencers per question so there are often over 1200 (or 400) total responses per behavior.

each graph also reports the proportion of women doing the behavior for each sample, displayed as a horizontal purple line. This provides additional context for assessing the effects of influencers as positive or negative based on comparison to the the sample average probability in addition to comparing to the reference value of ‘no one.’

In sum, the following series of graphs is organized temporally. It combines neutral behaviors with those that have biomedical recommendations. ASHAs will be on the left and Mothers on the right. For each behavior it is interesting to track if the nature of the influences have changed greatly from ASHAs to Mothers and what role the ASHA plays in influencing each behavior in the Mothers sample relative to the other influencers.

8.6.1 Early pregnancy

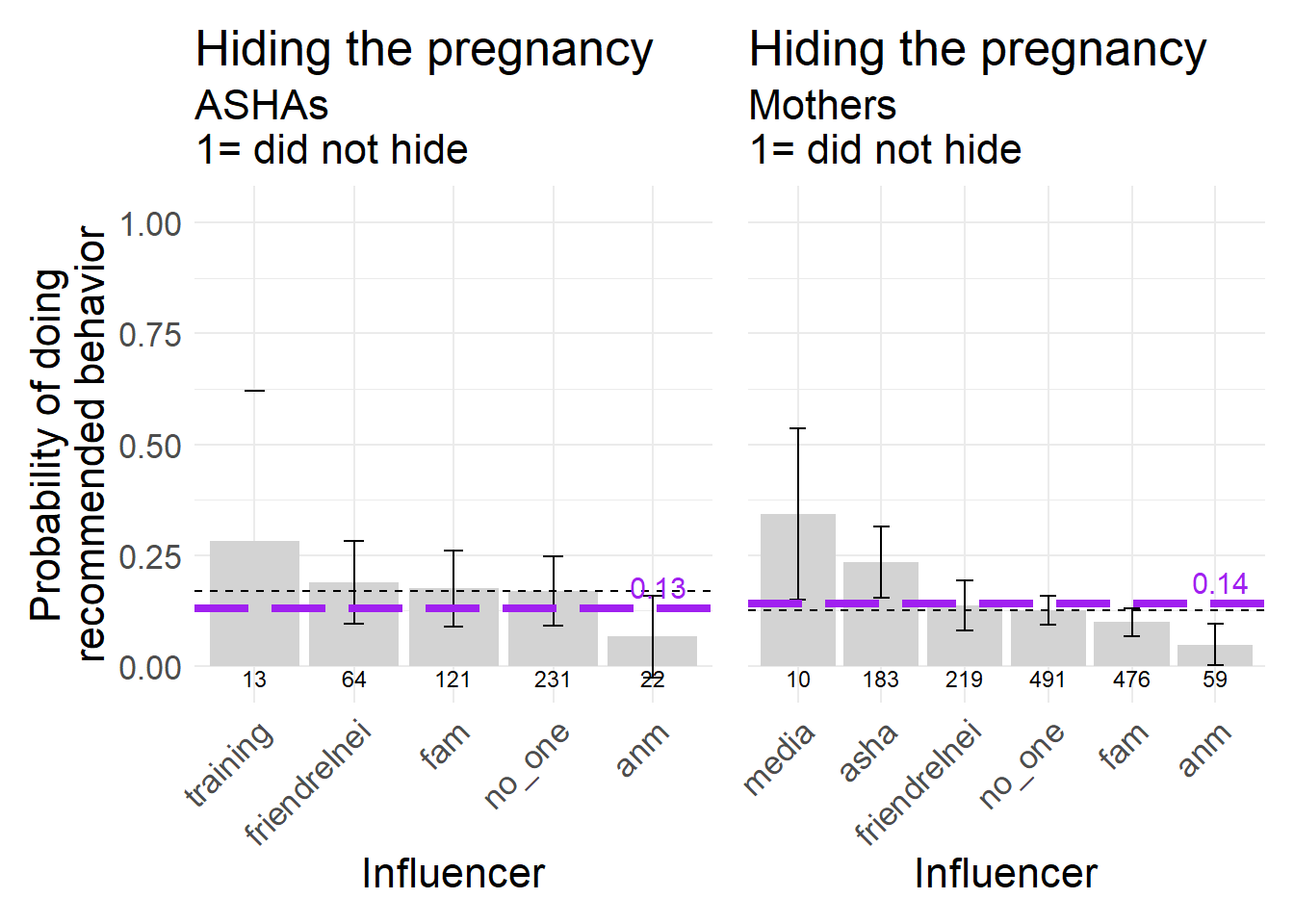

One of the behaviors earliest in the journey we examine is the decision if and when to reveal the pregnancy to outsiders. In most cultures this is a sensitive decision and a desire not to reveal the pregnancy for a certain amount of time is extremely common. There are no major positive influencers in resisting the tendency conceal the pregnancy in either dataset. Media was named only 10 times but does increase the predicted probability that a woman reveals her pregnancy in the first two months relative to no one, but overall its the lack of significant sources of influence that’s of note here.

Figure 8.9: Hiding the pregnancy from outsiders, a behavior biomedically recommended not to do (inasfar as it means also hiding the pregnancy from the ASHA or other health professionals), 1 = did NOT conceal the pregnancy for more than the first two months.

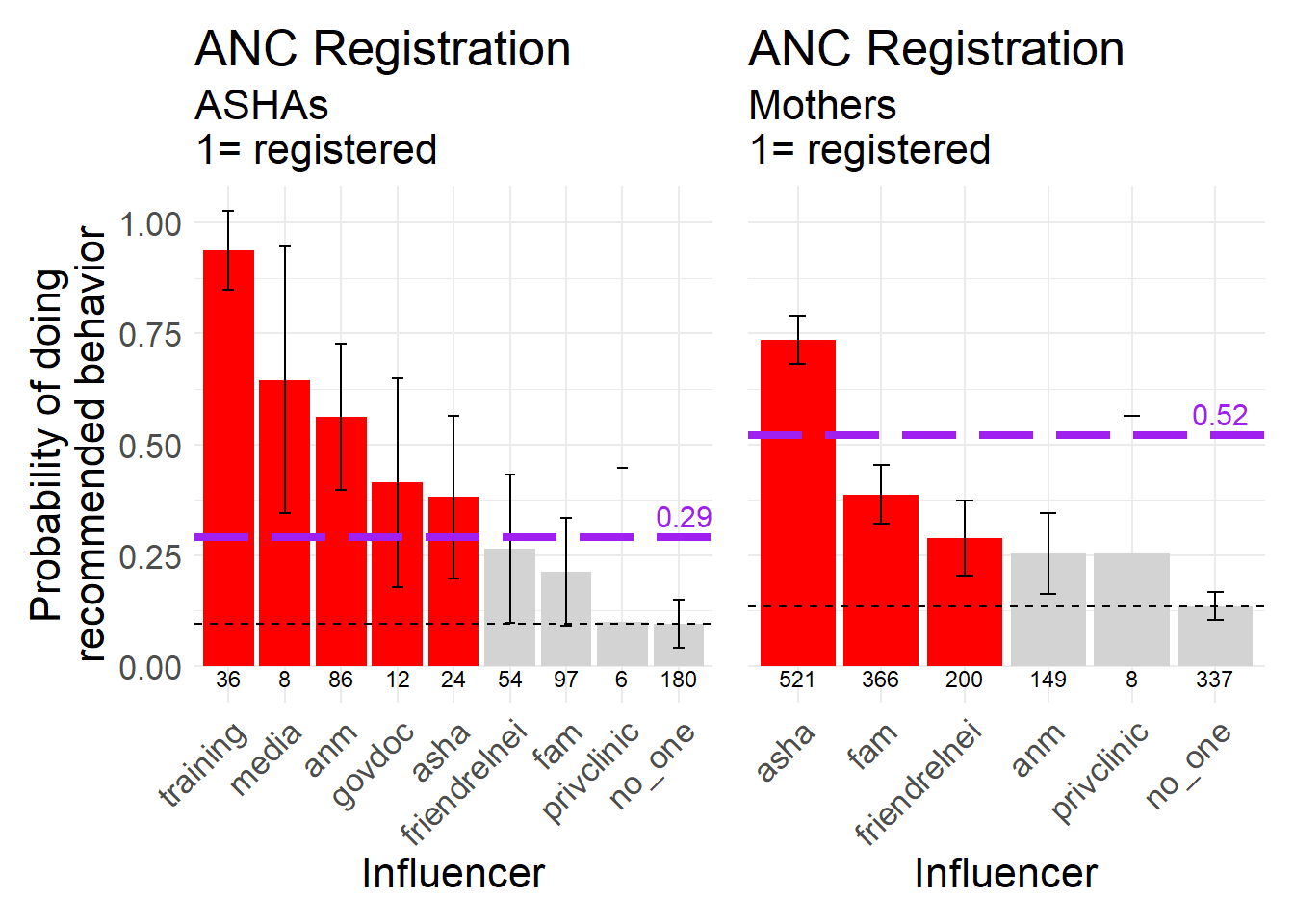

Second, we examine variation in a connected behavior, registering for ante-natal care (ANC). If women are concealing the pregnancy they are generally not receiving formal ANC care, which is of larger health concern than revealing the pregnancy per se. The Dai is not mentioned often enough in association with this behavior to be included in either dataset. The ASHA is the most named and has the strongest positive influence for ANC registration among Mothers.

Figure 8.10: Timely ANC Registration, a biomedically recommended behavior, 1 = registered within the first trimester

8.6.2 During Pregnancy

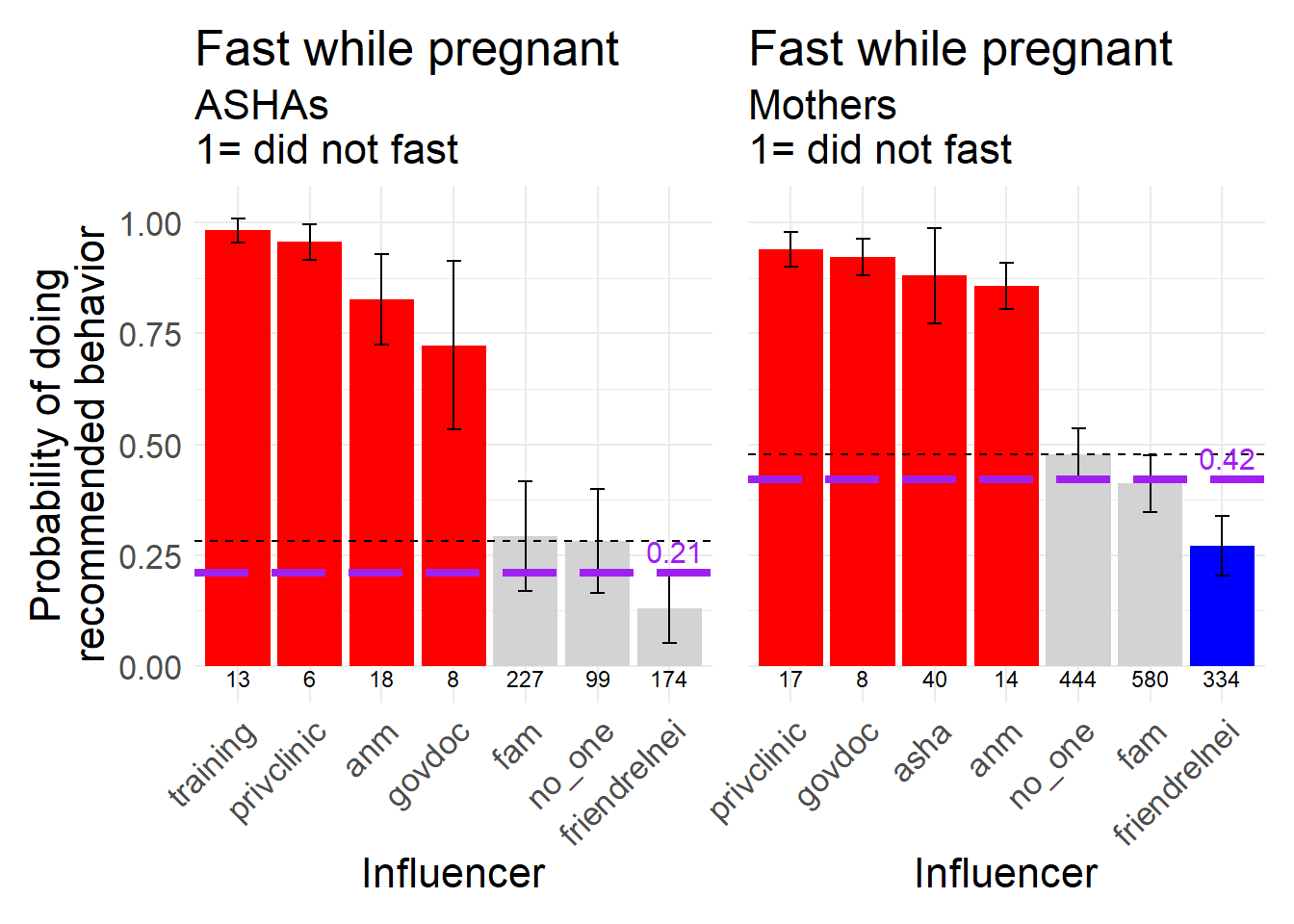

Next, we consider several behaviors that cover the period of pregnancy in general, starting with fasting while pregnant. Fasting while pregnant is generally not recommended because many women are under-nourished and caloric intake should ideally increase during pregnancy. However, it is possible that women who reported fasting here many simply avoid certain foods one day a week, or something of similar impact. In both datasets we see formal and medical sources raising the probability that women do not fast during pregnancy. We also see that the most commonly named influencers tend not to have effects on this behavior different from ‘no one.’ There are likely normative expectations for women to fast while pregnant (see friends, relatives, neighbors, lower right of Mothers graph).

Figure 8.11: Fasting while pregnant, a behavior that is biomedically recommended NOT to do, 1 = did not fast, as opposed to fasting regularly or fasting only for festivals.

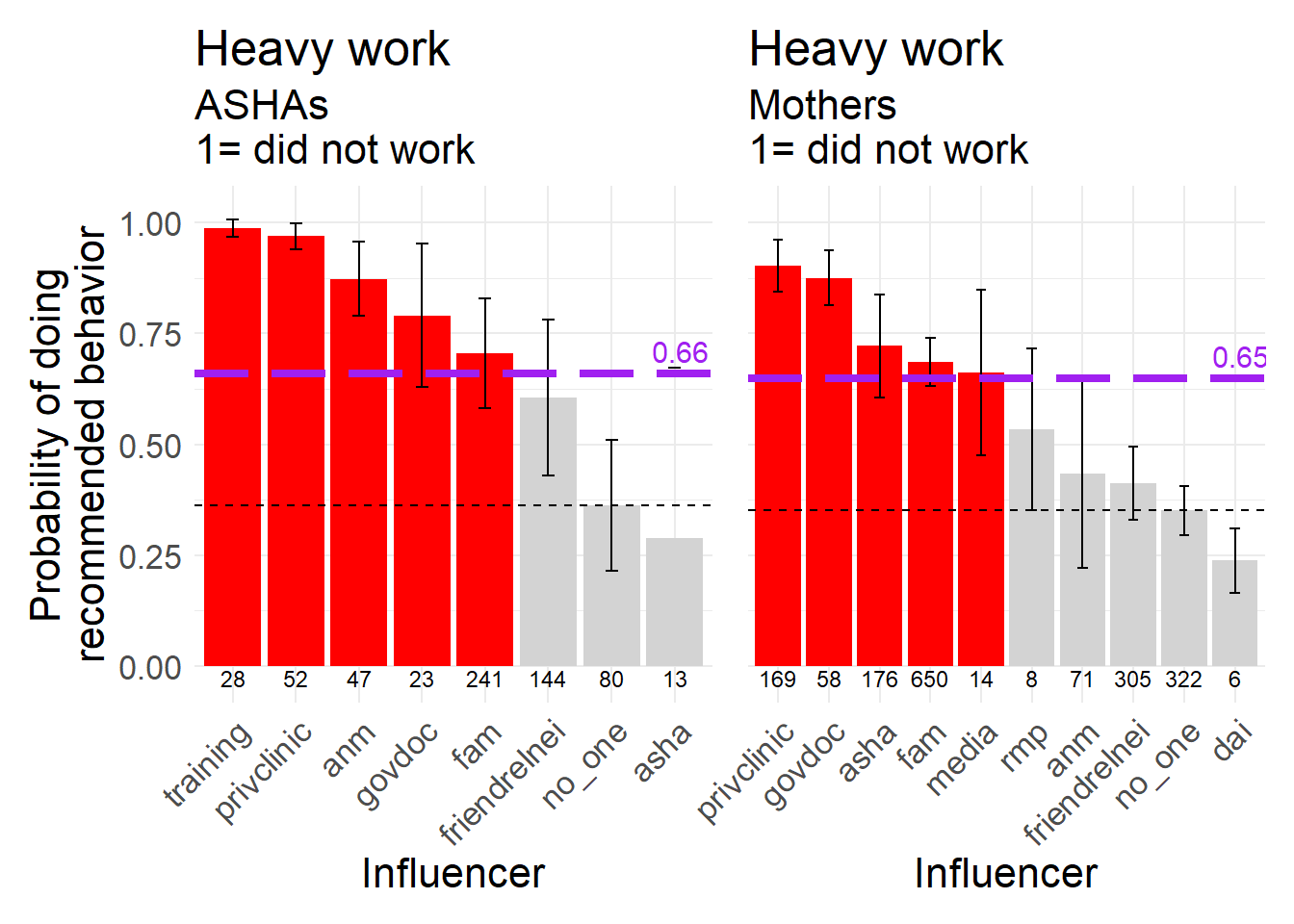

Similarly, pregnant women are generally expected not to engage in strenuous physical labor so we generally hope that they do not work during pregnancy. The only source increasing the probability that women work while pregnant is the Dai, but she was only mentioned by six women in association with this behavior.

Figure 8.12: Doing heavy work while pregnant, a behavior that is biomedically recommended NOT to do, 1 = did not work

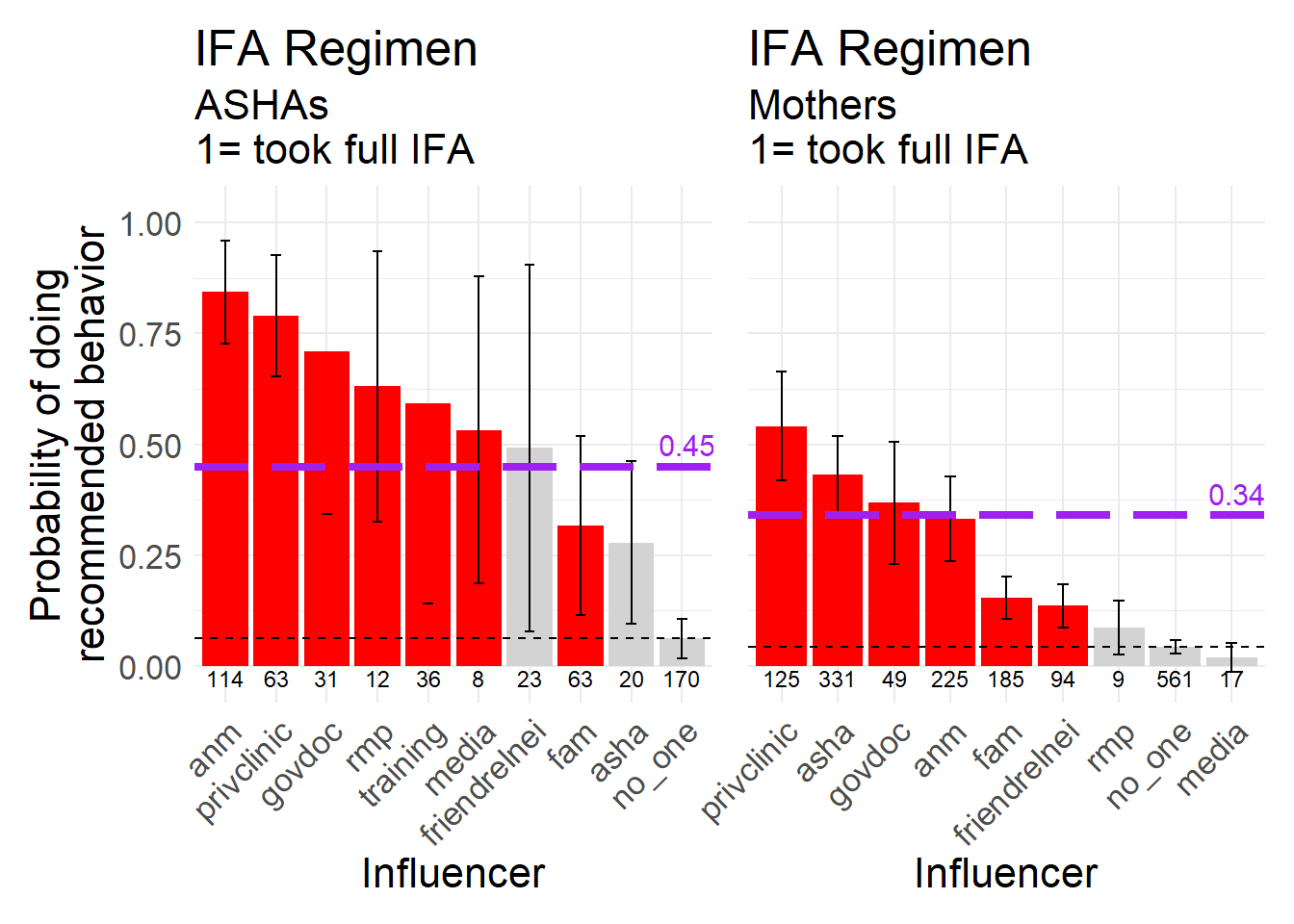

For IFA tablets, please recall that not following the recommended behavior of taking the full regimen includes partial uptake and women who did not take any at all (see Chapter 6 for a breakdown of these numbers). As most ASHAs did not have ASHAs during their last pregnancy it is not a surprise that they don’t associate taking IFA with ASHAs as much as they do with ANMs. In the Mothers dataset, note that while ASHAs have a strong positive impact on women taking IFA, the most commonly named source is no one and the associated probability with no one is extremely low.

Figure 8.13: IFA Regimen, a biomedically recommended behavior, 1 = took the full regimen (as opposed to partial or none).

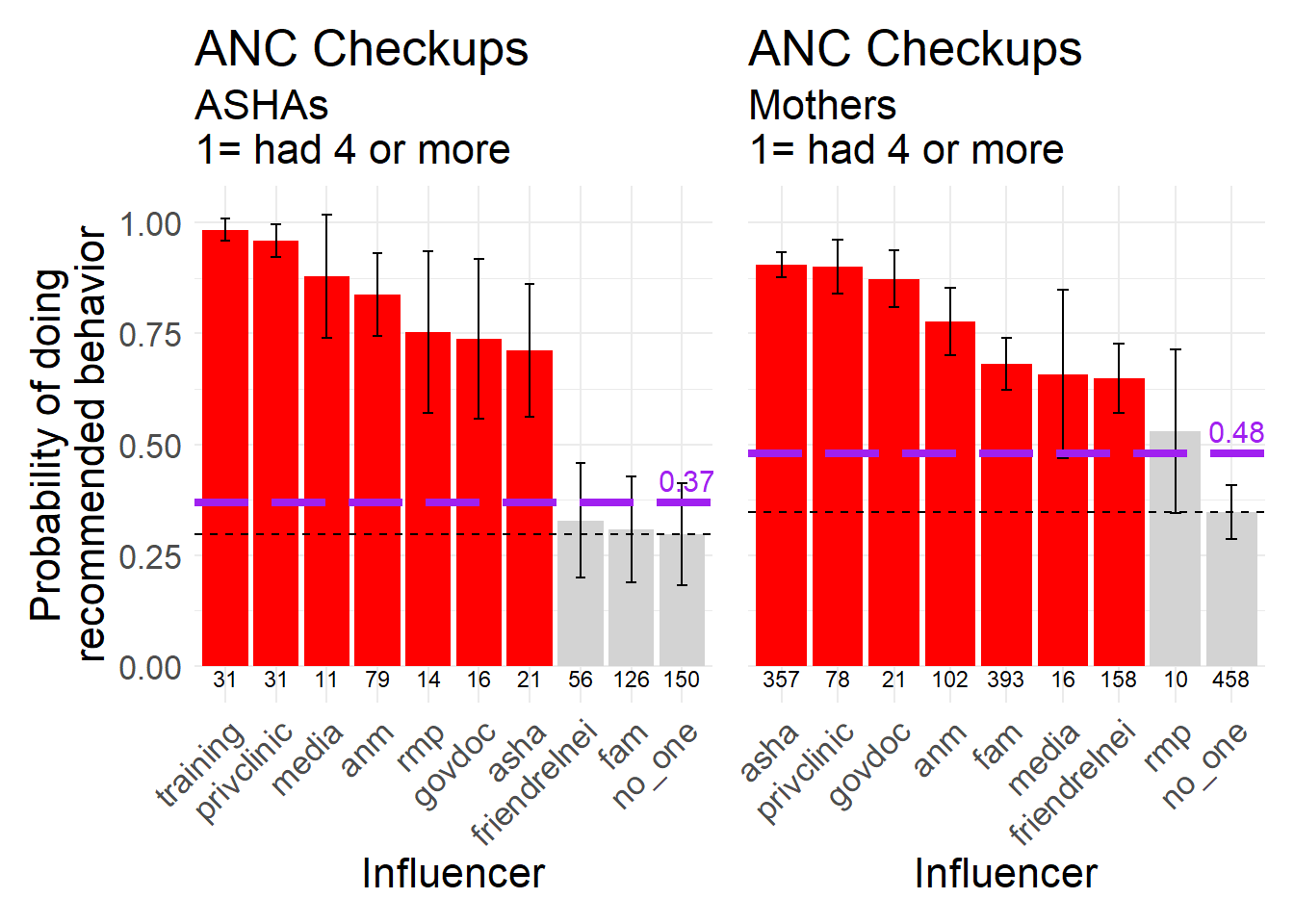

The official recommendation is for mothers to have 4 or more ANC checkups. These are visits to a facility that occur out of the home. The ASHA may assist in facilitating the visits.

Figure 8.14: 4 or more ANC checkups, a biomedically recommended behavior, 1 = 4 or more checkups (as opposed to none to 3).

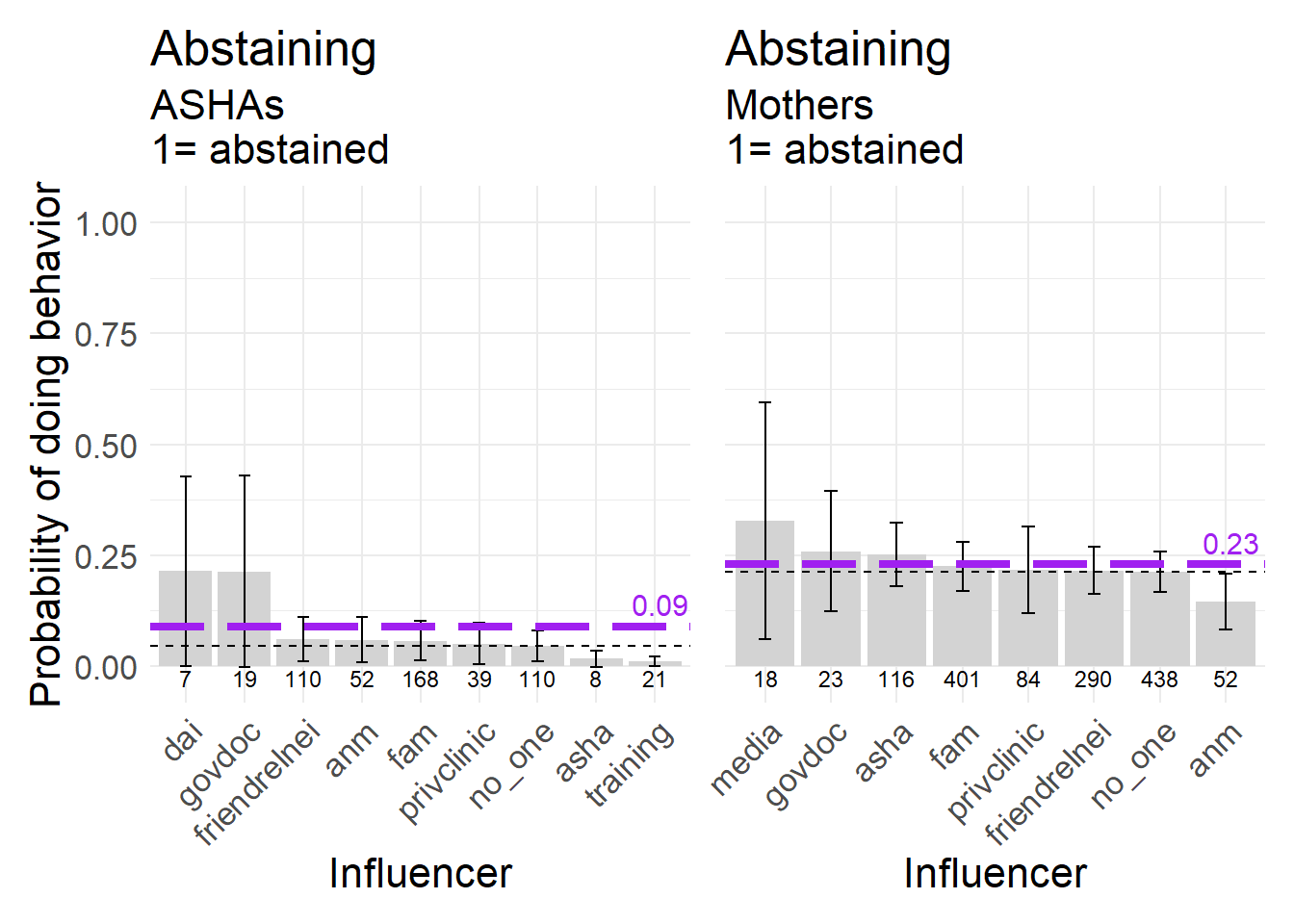

Project RISE’s qualitative data collection recorded several instances of women saying that they avoided sexual intercourse during pregnancy, often due to a concern that this could negatively impact the physical appearance or well being of the fetus. In both cases the most commonly named sources of influence are similar but none had a major impact on the probability that a woman abstained relative to no one.

Figure 8.15: Abstaining from sexual intercourse during pregnancy, a neutral behavior, 1 = abstained.

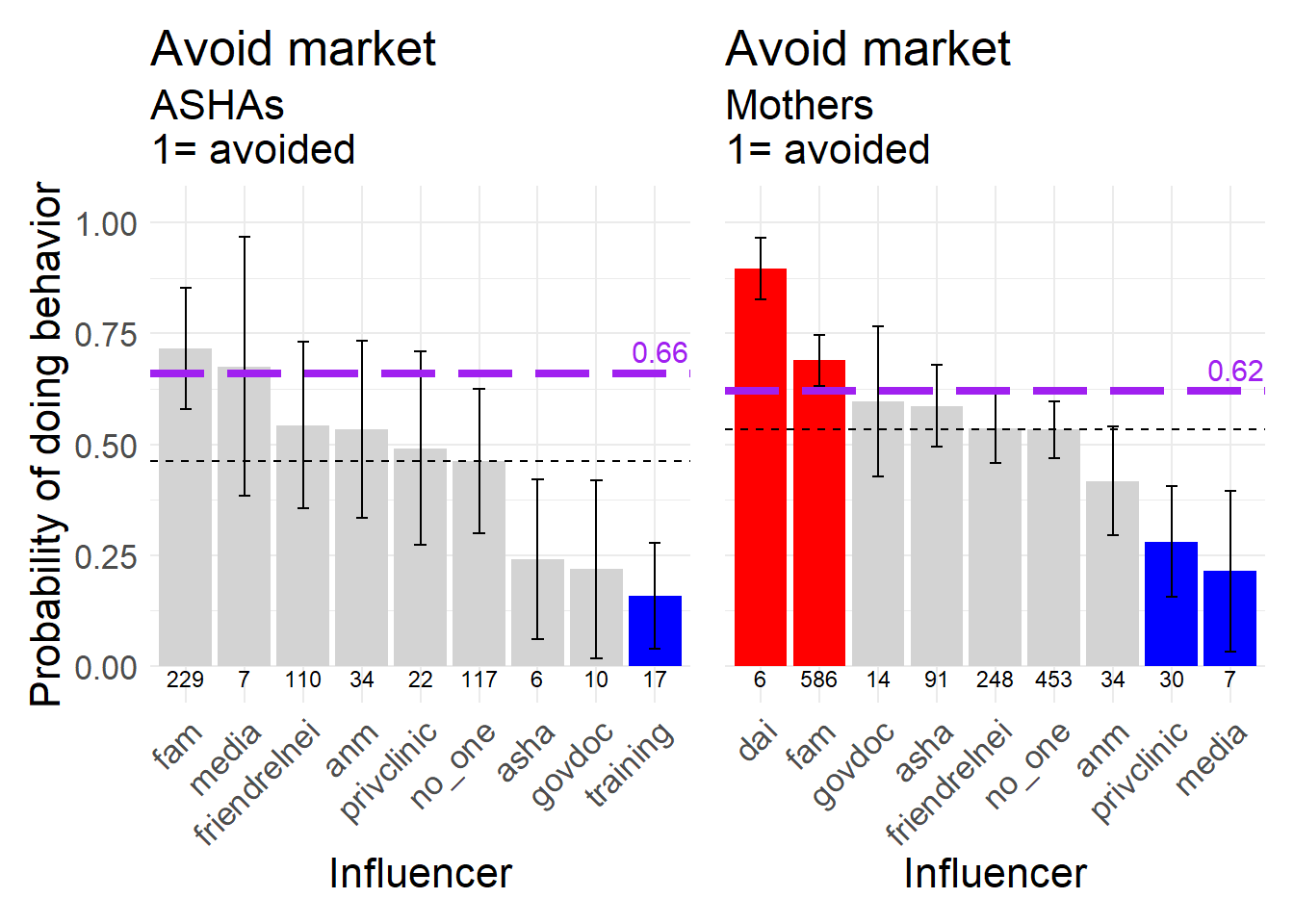

There are many reasons why a woman might avoid markets during pregnancy, from wanting to limit physical activity to wanting to avoid evil eye and some forms of witchcraft that can occur. We coded this behavior as neutral because is arguably not necessarily strenuous and other many circumstances a pregnant woman can safely go to a market. Interestingly, for ASHAs their training was was associated with lowering the probability that they went to market. We need to understand what specific messages in the training were responsible for this but it could be a general recommended limitation on mobility and activity. Mothers who went to market were positively influenced by Dais (only named six times) and by family, with private clinics and media lowering the probability. Family was the most commonly named influence for this behavior in both datasets.

Figure 8.16: Avoiding going to the market during pregnancy, a neutral behavior, 1 = avoided the market.

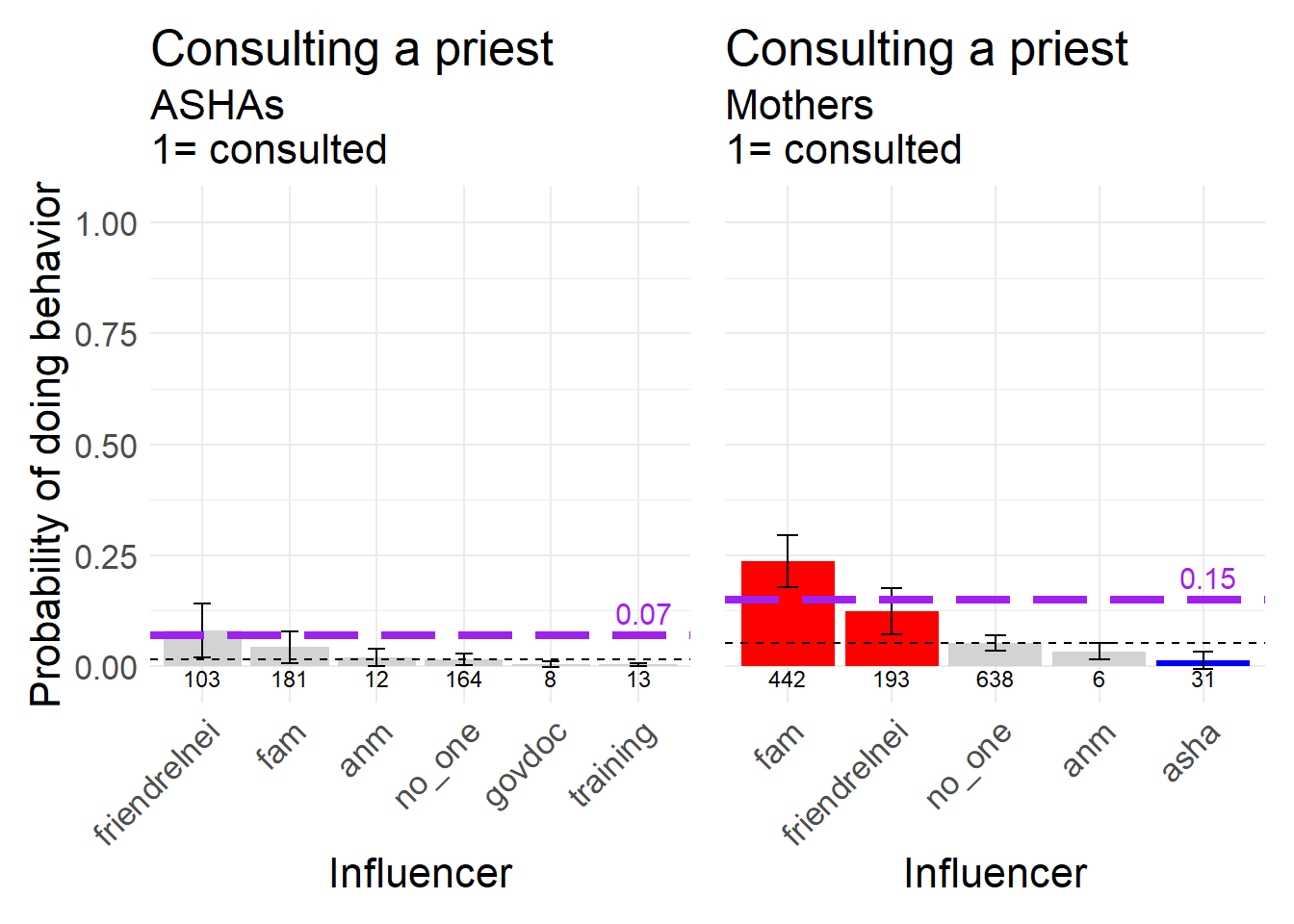

We also asked women if they consulted a priest (Mulana or Pandit) during pregnancy. In both datasets no one was the most commonly chosen influencer but in the Mother data family and friends/relatives/neighbors increased the probability of calling a priest while the ASHA lowered the probability.

Figure 8.17: Consulting a religious leader during pregnancy, a neutral behavior, 1 = consulted.

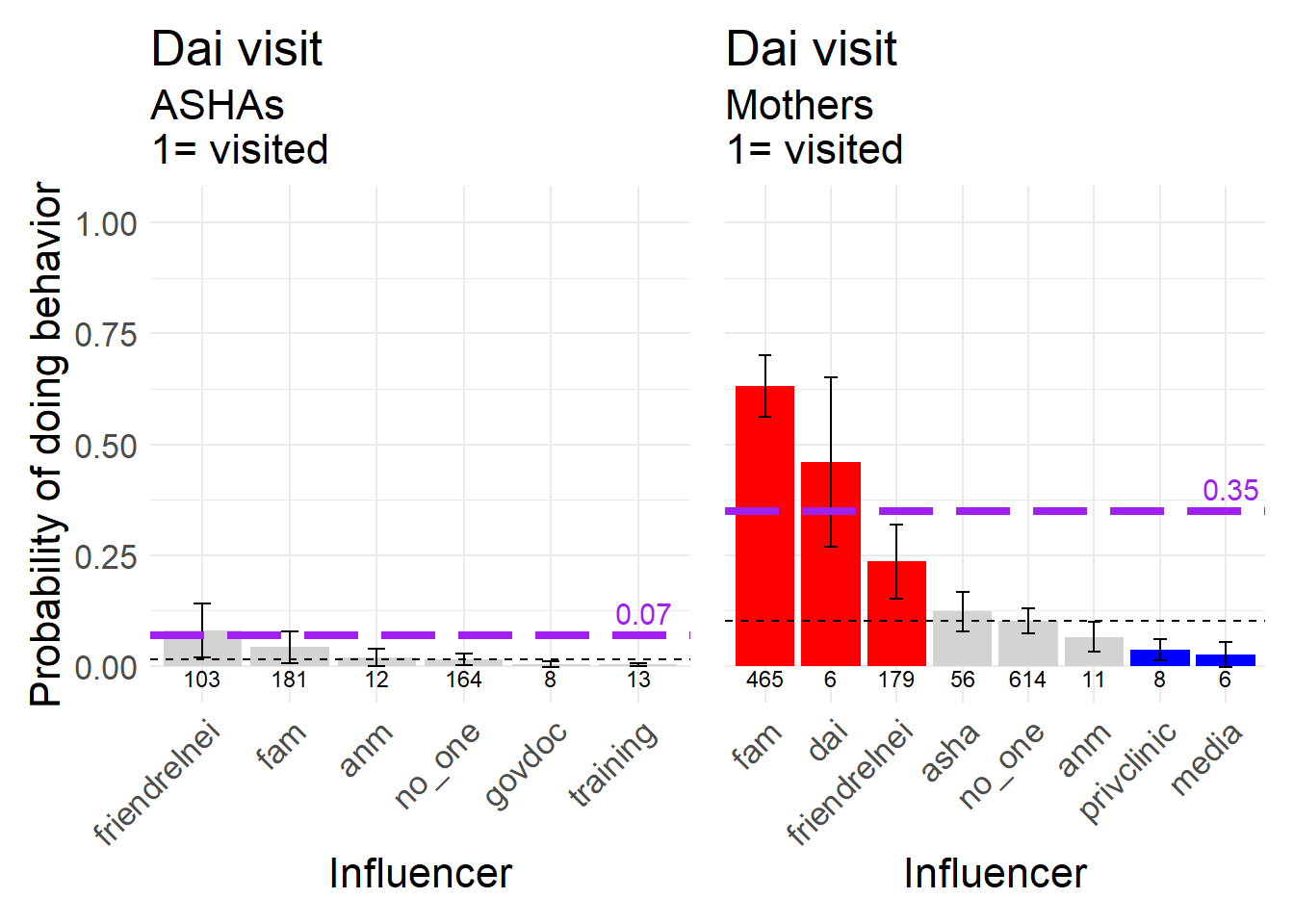

Figure 8.18: Dai visit during pregnancy, a neutral behavior, 1 = Dai visited.

8.6.3 Near Delivery

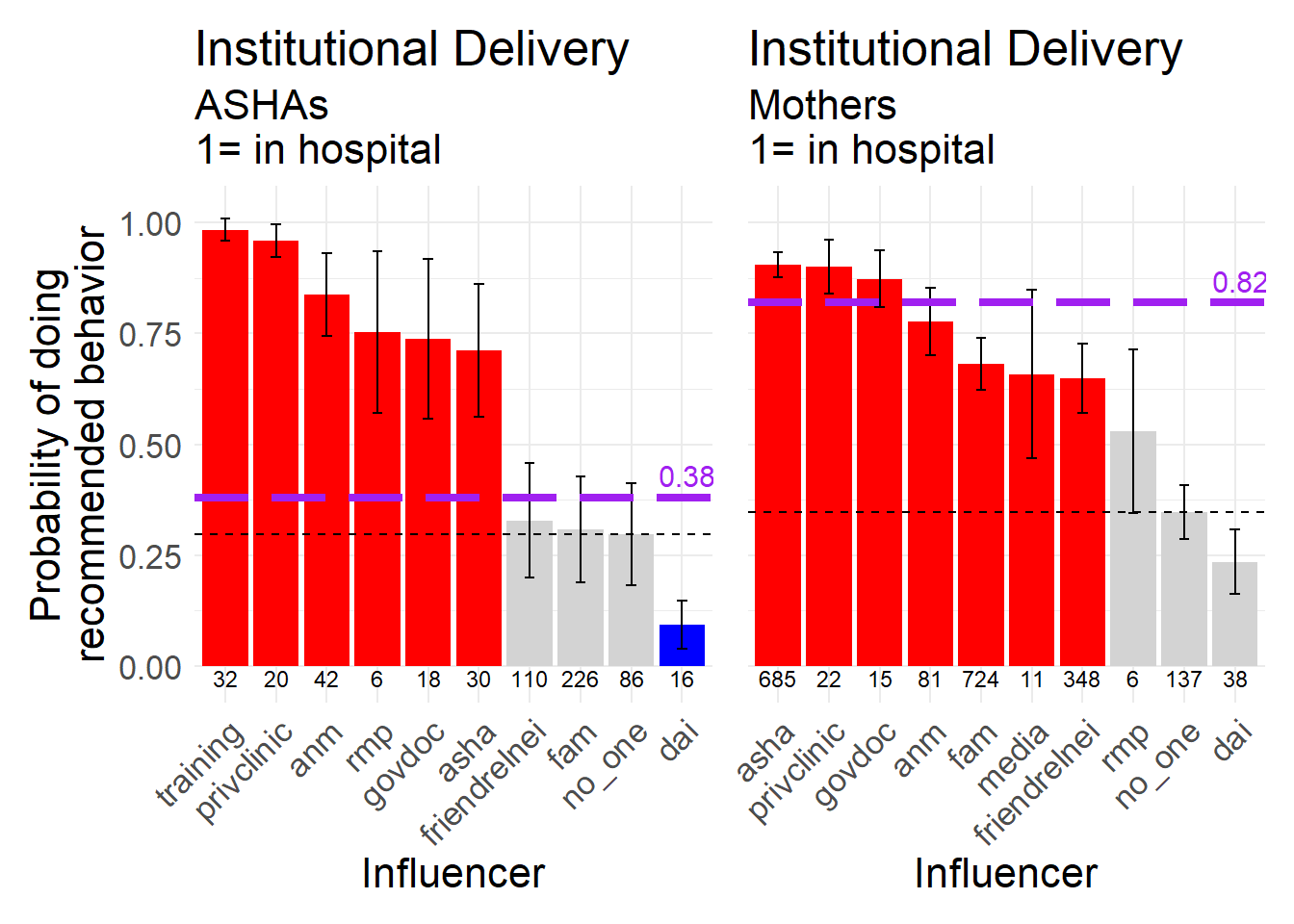

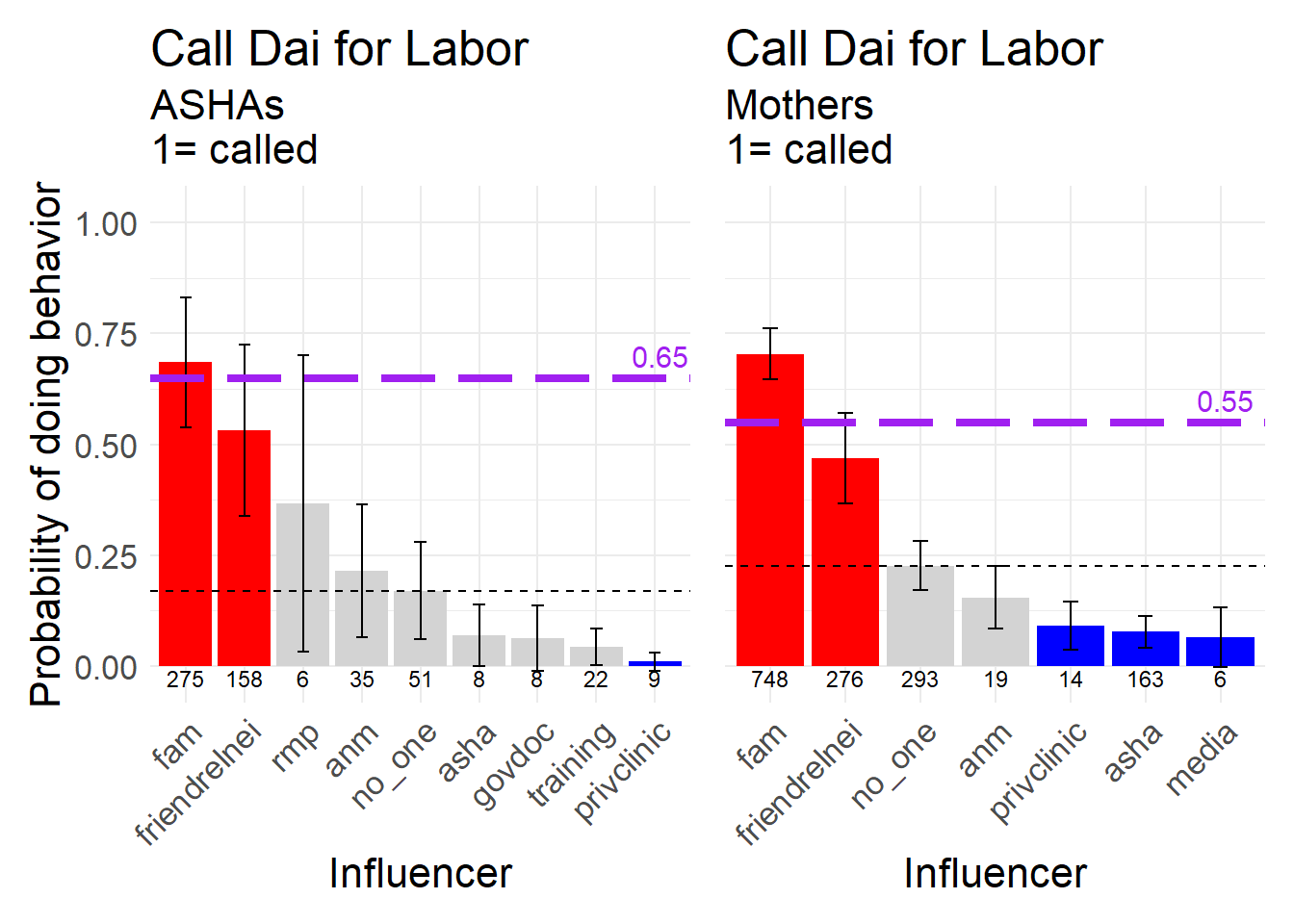

We examined two behaviors that represent decisions that take place near delivery. One is where to deliver, at home or in a hospital, and the other is whether to call a Dai when labor starts.

Keeping in mind that the frequency with which Mothers have institutional deliveries is much greater than that for ASHAs, we see some interesting shifts in the nature of the influence in each dataset as well. For instance, among ASHAs Family and Friends/relatives/neighbors were both neutral in terms of raising the probability of institutional delivery, but are positive among Mothers. Note further that the ASHA is the second most frequently named influencer (after Family) and the strongest positive influence among Mothers. In both datasets the Dai lowers the probability of institutional delivery relative to no one.

Figure 8.19: Hospital delivery, a biomedically recommended behavior, 1 = delivered in a hospital.

On the other hand, calling a Dai for labor has changed less than the decision of where to have the delivery.

Figure 8.20: Calling the dai when labor started, a neutral behavior, 1 = called the dai.

8.6.4 Post-Partum

Several of the focal RISE behaviors are concentrated in the first week post-partum.

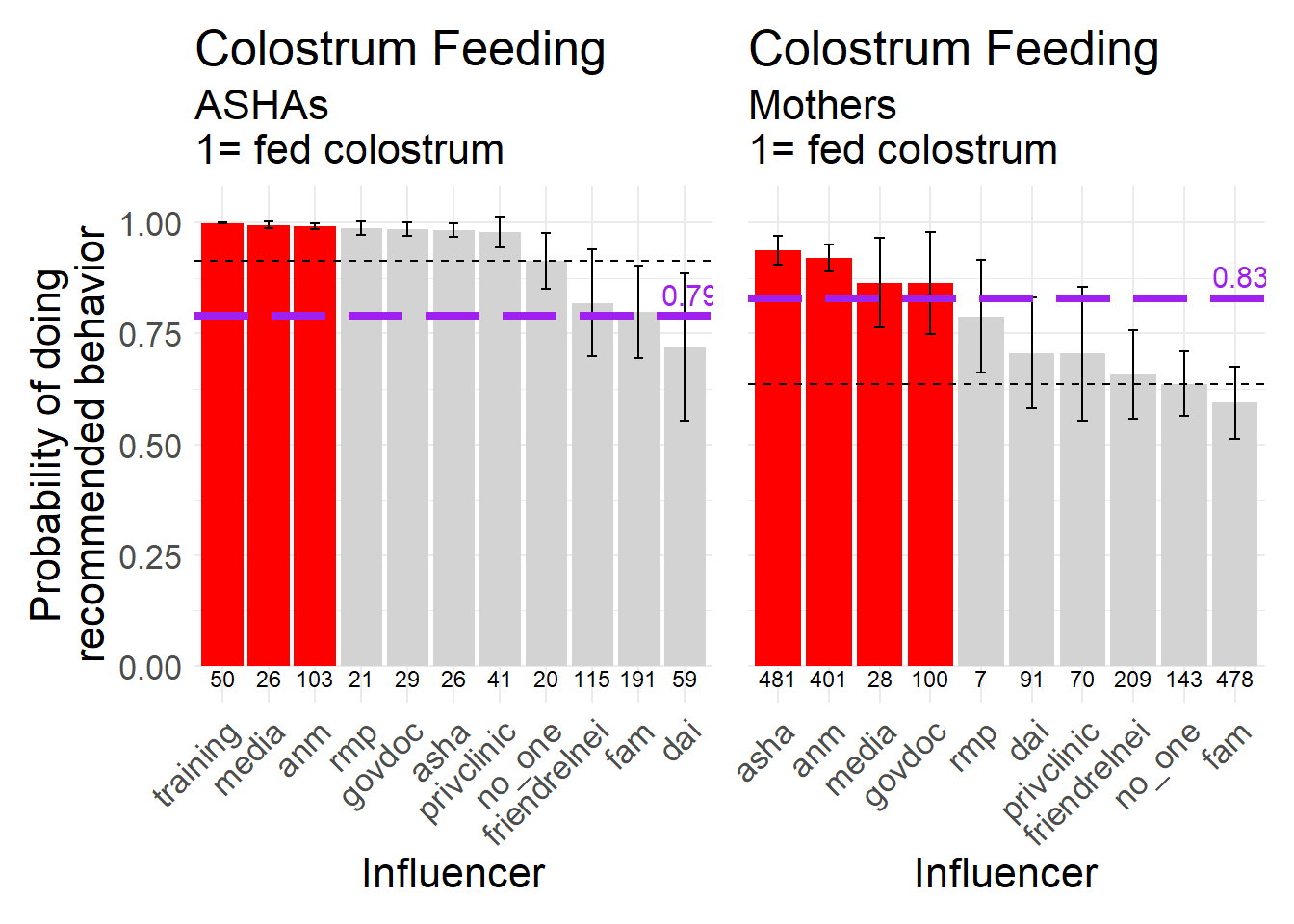

For the ASHAs we see that nearly every influencer has a very strong positive effect on the probability that women feed colostrum, with five having an influencer greater than the category of no one. That so many of the ASHA values are approaching 1.0 is not quite clear. For the Mother data, Family is mentioned almost as often as the ASHA as a source of influence (489 mentions vs 492), yet they represent opposite ends of the spectrum in terms of the nature of the influence. Women influenced by Family on this decision are much less likely to feed colostrum than those influenced by ASHAs or ANMs.

Figure 8.21: Feeding the newborn colostrum, a biomedically recommended behavior, 1 = fed the baby colostrum.

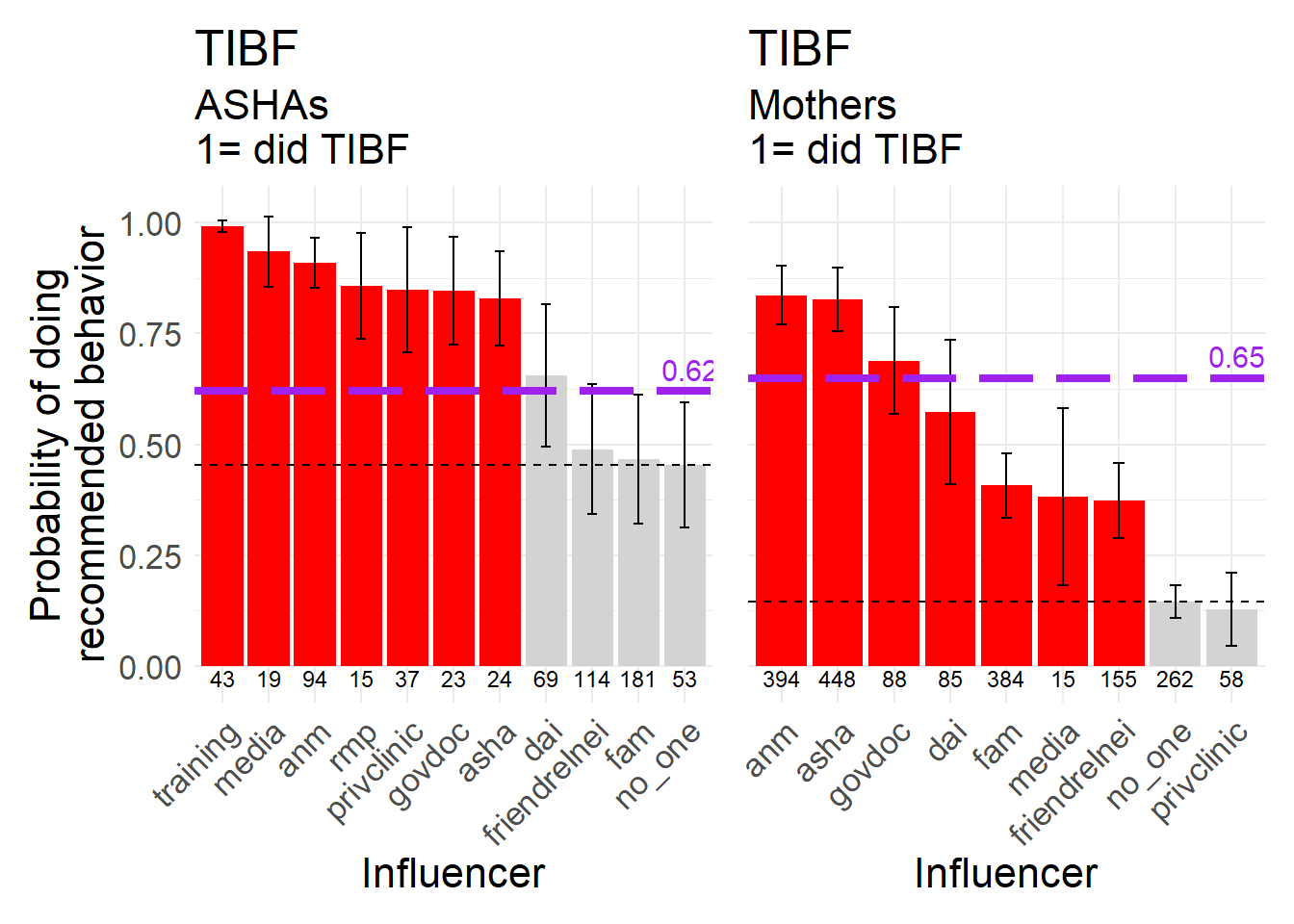

Timely initiation of breast feeding is a key behavior that many global health organizations hope to see increase in importance and frequency. Every medically-aligned and most normative sources of influence increase the probability of adopting TIBF relative to no one in both datasets.

Figure 8.22: Timely initiation of breast feeding (TIBF), a biomedically recommended behavior, 1 = initiated breastfeeding within the first hour after birth.

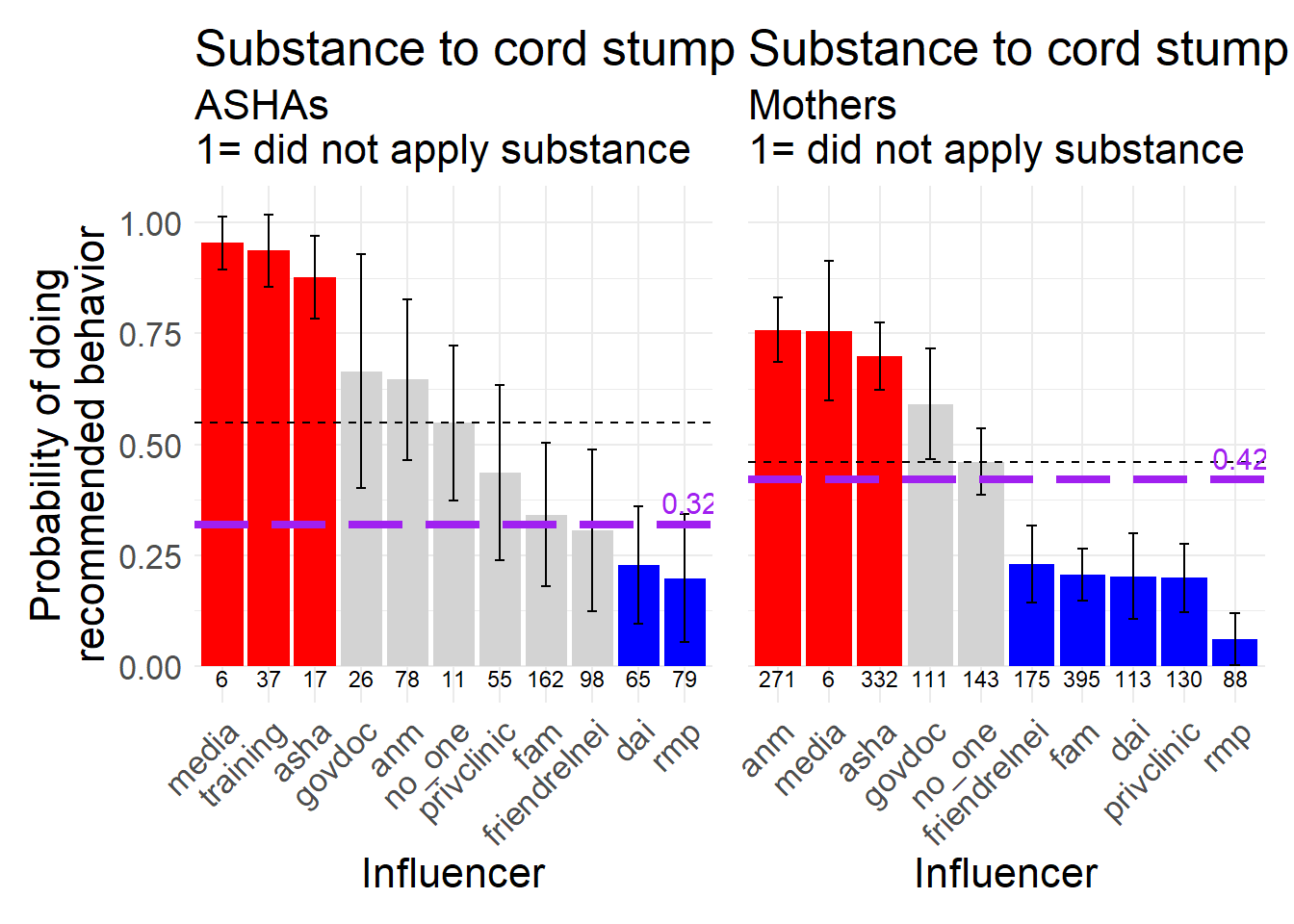

Cord care is another behavior that receives relatively much attention. Here we see several sources of influence lowering the probability that women engage with the recommended behavior, especially in the Mothers dataset. The two main normative influences, Family and Friends/relatives/neighbors, both increase the probability that women apply a substance to the cord stump relative to no one. The only influencers that are frequently named and having a positive influence are ANMs and ASHAs. It is not clear why the category of private clinic has an effect that is negative relative to ‘no one,’ but it may be that they sometimes sell the blue medicine that is commonly used to treat the cord stump (see Chapter 7).

Figure 8.23: Applying a substance to the umbilical cord stump, a behavior biomedically recommended not to do, 1 = did NOT apply a substance to the cordstump.

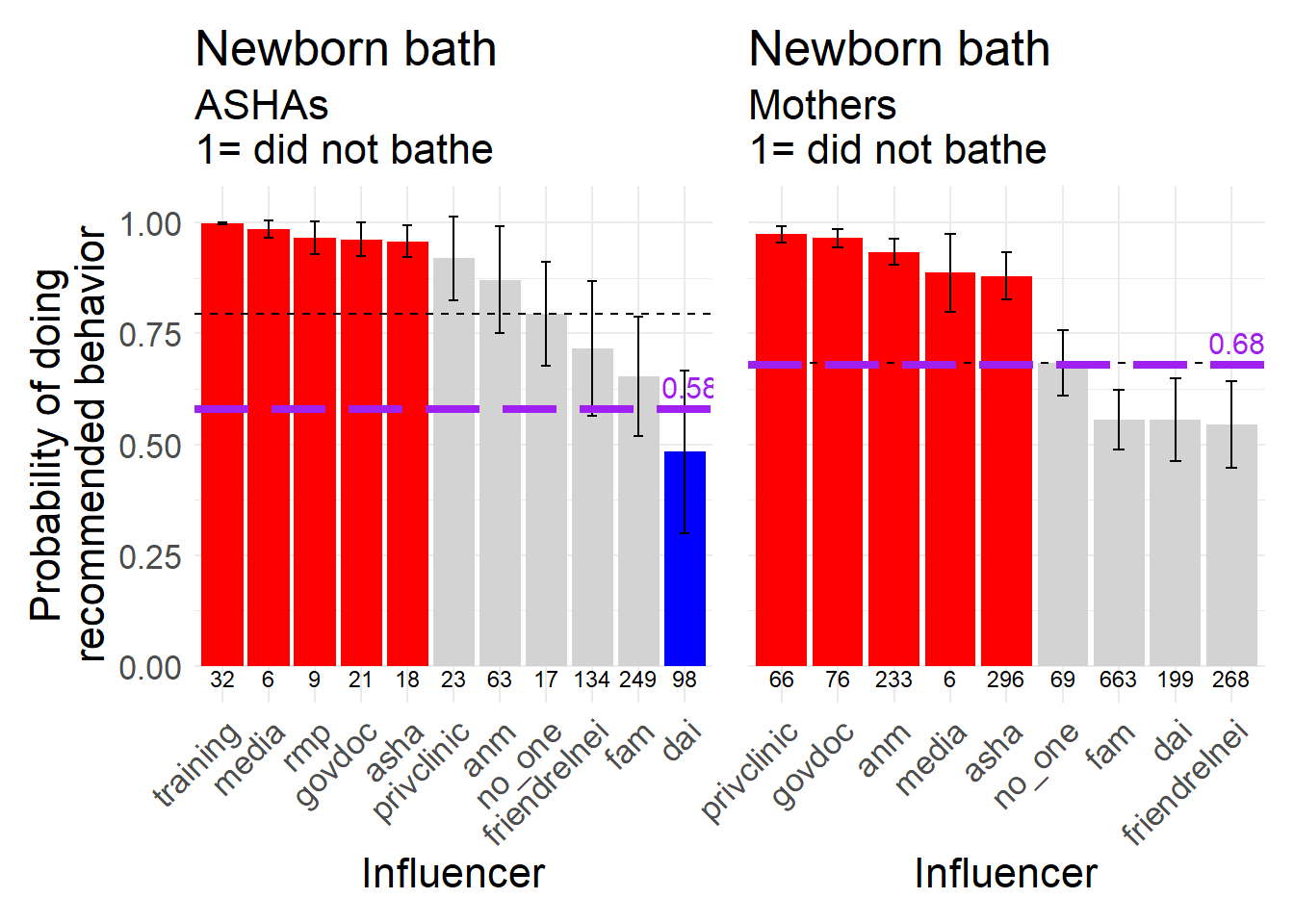

Bathing the newborn should not be done within 24 hours of birth. The Dai and Family both decrease the probability of complying with the recommendation to not bathe.

Figure 8.24: Bathing the newborn shortly after birth, a behavior biomedically recommended not to do, 1 = did NOT give newborn a bath within first 24 hours after birth.

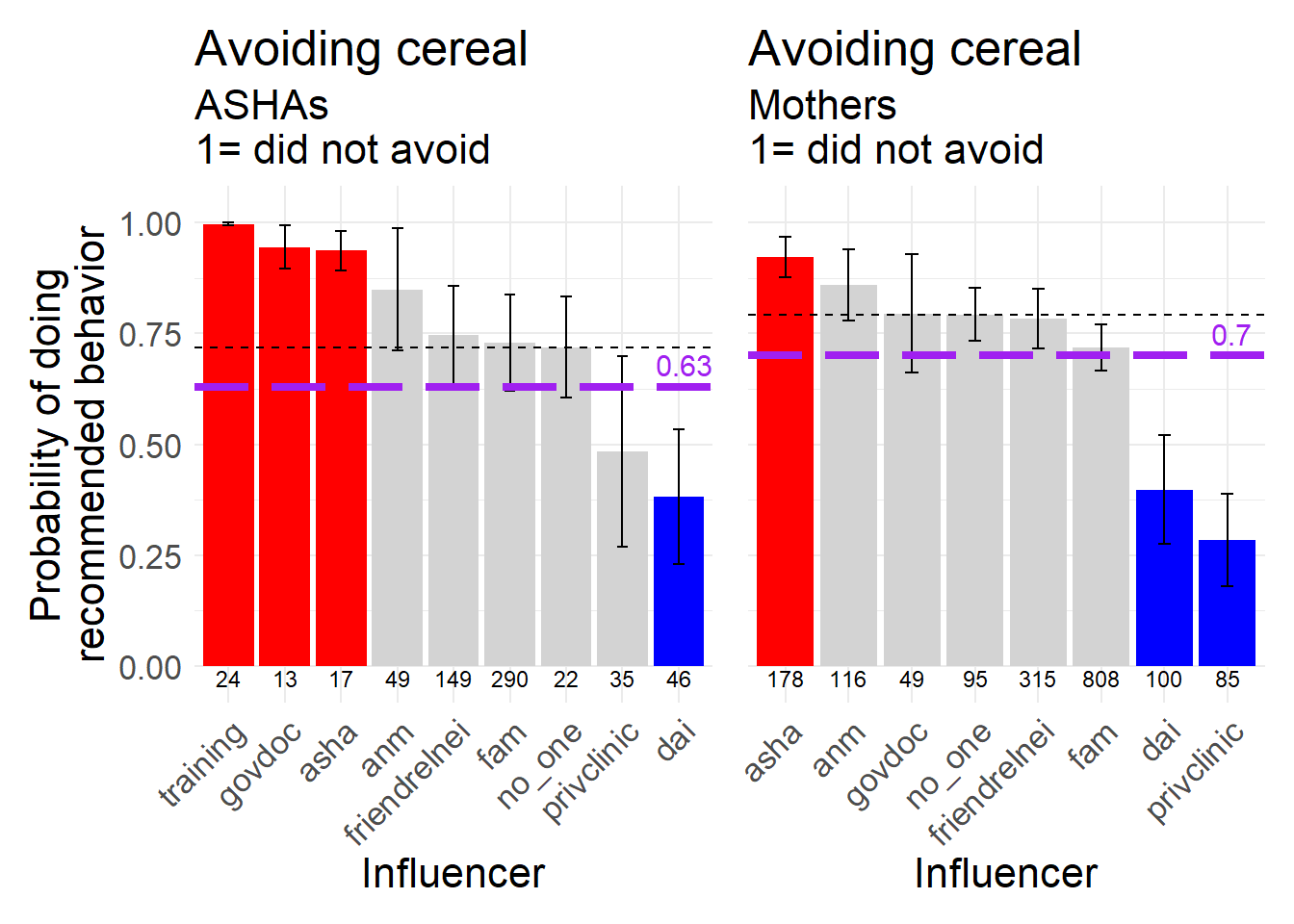

The qualitative data collection also revealed that women in Bihar sometimes avoid cereal based foods in the first week after delivery. In the Mother dataset the ASHA is the only source of influence that has an effect significantly better than no one for not avoiding cereal. Likewise, the Dai is the only source that lowers the probability relative to no one. Family is the most commonly named influence for this behavior, and ‘no one’ is named relatively rarely.

Figure 8.25: Avoidng cereal-based foods after delivery, a behavior biomedically recommended not to do, 1 = did NOT avoid.

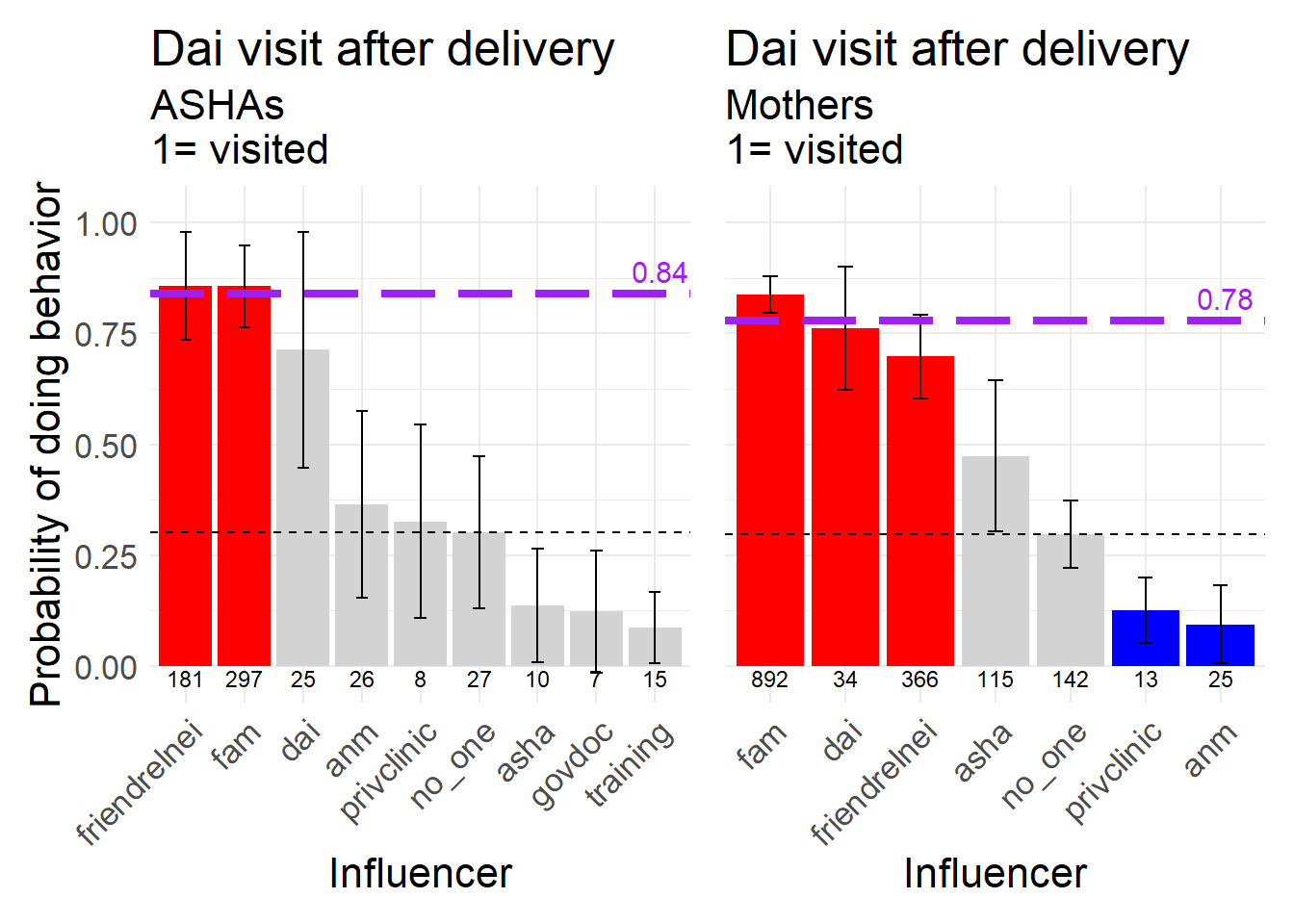

Having the Dai visit the household after delivery has a fairly similar profile of influence in each sample, with the top three influencers being Family, Friends/relatives/neighbors, and the Dai herself.

Figure 8.26: A visit from the Dai after delivery, a neutral behavior, 1 = dai visited.

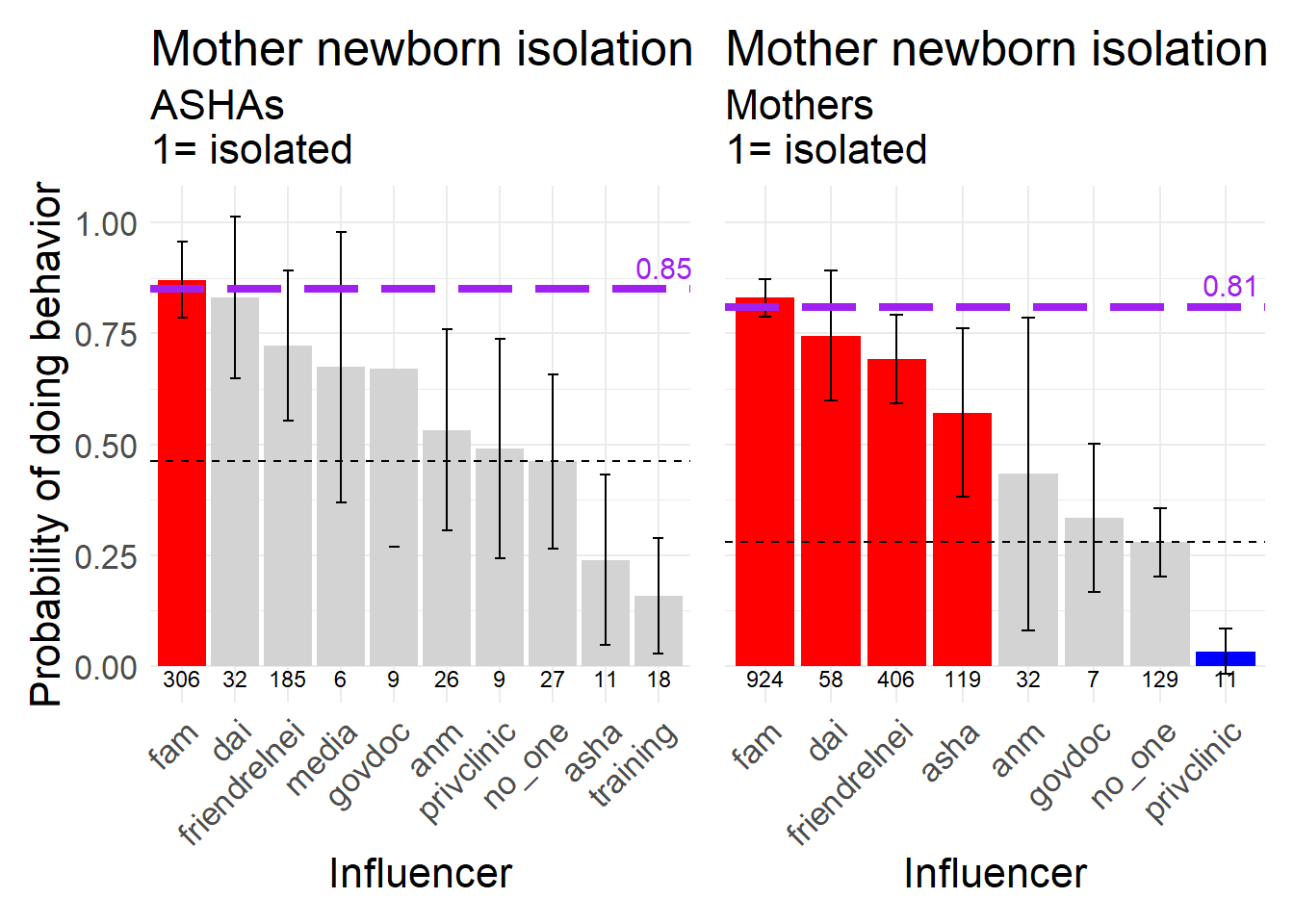

A neutral post-partum behavior, also identified in the qualitative studies, is to have the mother and newborn isolate together for a period of time after the delivery. This is clearly a normative and household decision governed by individuals close to the woman. Only the private clinic in the Mother dataset lowered the probability of a Mother doing this.

Figure 8.27: Mother and newborn isolating together after delivery, a neutral behavior, 1 = isolated.

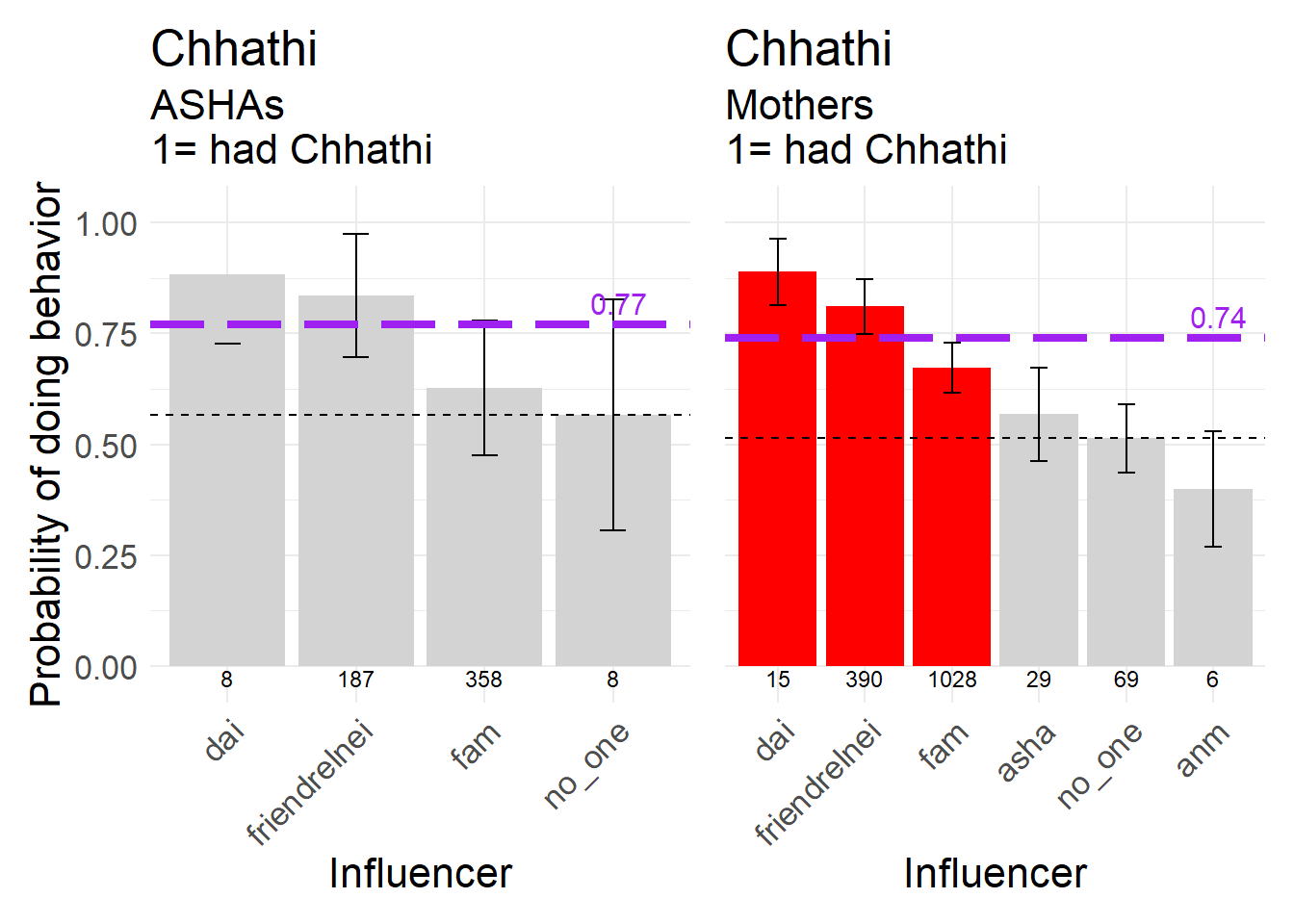

Lastly, Chhathi is a long-standing cultural ritual that typically comes on the sixth day after delivery. The most commonly named source for this behavior is the Family, but note that the ASHA is in the middle of the influencers for the Mother data.

Figure 8.28: Chhathi, a neutral behavior, 1 = Chhathi happened.

The sequence of behaviors here was presented roughly sequentially, from early pregnancy to delivery. But we could also have organized these by within the household to within the medical system, as this also illustrates contrasts in influence.

The ASHA responses do seem to imply a knowledge of who should be associated with the recommended practices.

In many cases during the sequence we see an intuitive shift in the nature of influence from ASHAs to Mothers. In the Mother dataset there is increased reliance on medical sources but for more traditional behaviors many of the influencer effects are quite similar between the two, implying some stability.