2.7 Model fit

2.7.1 The \(R^2\)

The coefficient of determination \(R^2\) is closely related with the ANOVA decomposition. It is defined as

\[\begin{align} R^2:=\frac{\text{SSR}}{\text{SST}}=\frac{\text{SSR}}{\text{SSR}+\text{SSE}}=\frac{\text{SSR}}{\text{SSR}+(n-p-1)\hat\sigma^2}. \tag{2.21} \end{align}\]

The \(R^2\) measures the proportion of variation of the response variable \(Y\) that is explained by the predictors \(X_1,\ldots,X_p\) through the regression. Intuitively, \(R^2\) measures the tightness of the data cloud around the regression plane. Check in Figure 2.17 how the value of \(\sigma^2\)46 affects the \(R^2.\)

The sample correlation coefficient is intimately related with the \(R^2.\) For example, if \(p=1,\) then it can be seen (exercise below) that \(R^2=r^2_{xy}.\) More importantly, \(R^2=r^2_{y\hat y}\) for any \(p,\) that is, the square of the sample correlation coefficient between \(Y_1,\ldots,Y_n\) and \(\hat Y_1,\ldots,\hat Y_n\) is \(R^2,\) a fact that is not immediately evident. Let’s check this fact when \(p=1\) by relying on \(R^2=r^2_{xy}.\) First, by the form of \(\hat\beta_0\) given in (2.3),

\[\begin{align} \hat Y_i&=\hat\beta_0+\hat\beta_1X_i\nonumber\\ &=(\bar Y-\hat\beta_1\bar X)+\hat\beta_1X_i\nonumber\\ &=\bar Y+\hat\beta_1(X_i-\bar X). \tag{2.22} \end{align}\]

Then, replace (2.22) in

\[\begin{align*} r^2_{y\hat y}&=\frac{s_{y\hat y}^2}{s_y^2s_{\hat y}^2}\\ &=\frac{\left(\sum_{i=1}^n \big(Y_i-\bar Y \big)\big(\hat Y_i-\bar Y \big)\right)^2}{\sum_{i=1}^n \big(Y_i-\bar Y \big)^2\sum_{i=1}^n \big(\hat Y_i-\bar Y \big)^2}\\ &=\frac{\left(\sum_{i=1}^n \big(Y_i-\bar Y \big)\big(\bar Y+\hat\beta_1(X_i-\bar X)-\bar Y \big)\right)^2}{\sum_{i=1}^n \big(Y_i-\bar Y \big)^2\sum_{i=1}^n \big(\bar Y+\hat\beta_1(X_i-\bar X)-\bar Y \big)^2}\\ &=r^2_{xy}. \end{align*}\]

As a consequence, \(r^2_{y\hat y}=r^2_{xy}=R^2\) when \(p=1.\)

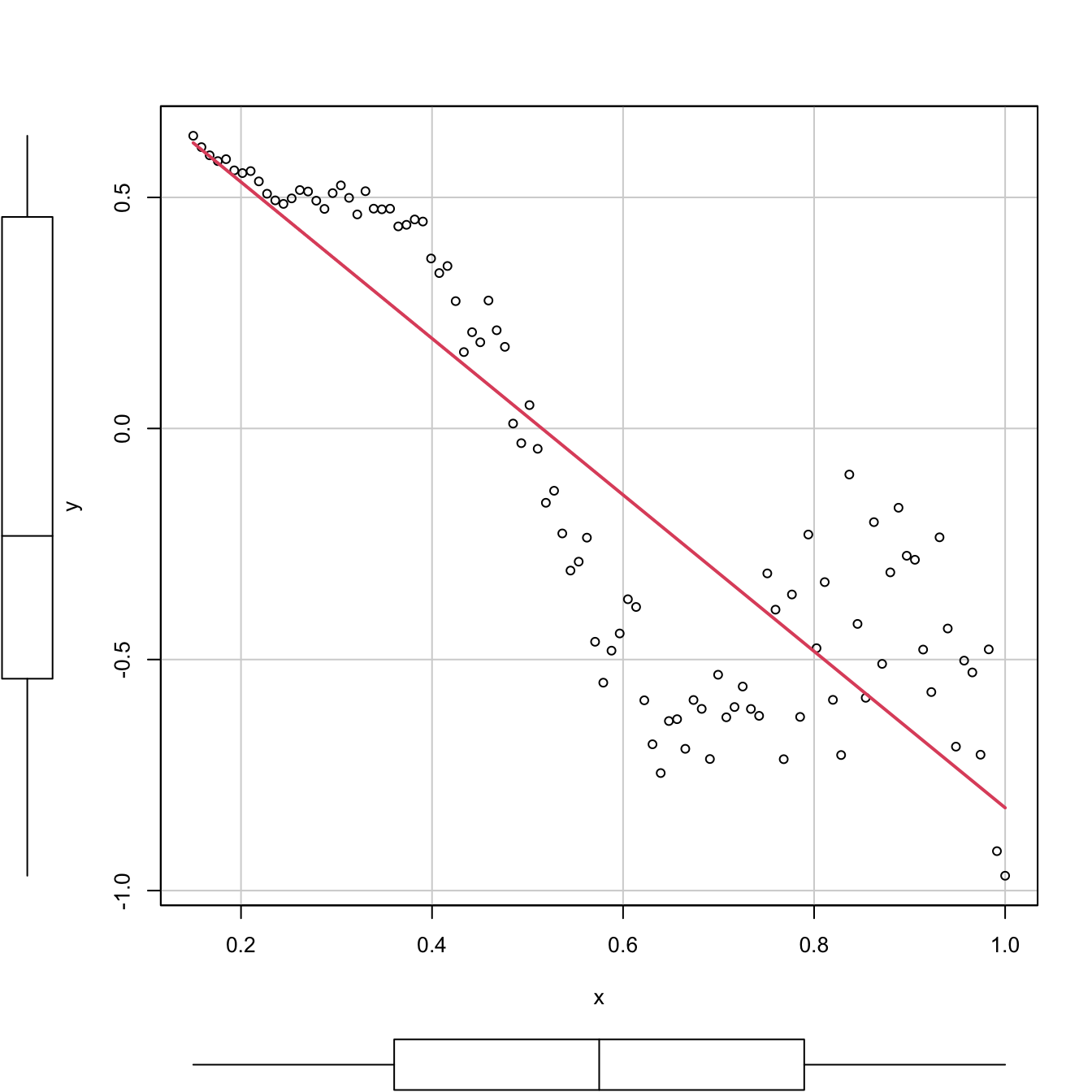

Trusting the \(R^2\) blindly can lead to catastrophic conclusions. Here are a couple of counterexamples of a linear regression performed in a data that clearly does not satisfy the assumptions discussed in Section 2.3 but, despite that, the linear models have large \(R^2\)’s. These counterexamples emphasize that inference, built on the validity of the model assumptions,47 will be problematic if these assumptions are violated, no matter what is the value of \(R^2.\) For example, recall how biased the predictions and its associated CIs will be in \(x=0.35\) and \(x=0.65.\)

# Simple linear model

# Create data that:

# 1) does not follow a linear model

# 2) the error is heteroscedastic

x <- seq(0.15, 1, l = 100)

set.seed(123456)

eps <- rnorm(n = 100, sd = 0.25 * x^2)

y <- 1 - 2 * x * (1 + 0.25 * sin(4 * pi * x)) + eps

# Great R^2!?

reg <- lm(y ~ x)

summary(reg)

##

## Call:

## lm(formula = y ~ x)

##

## Residuals:

## Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

## -0.53525 -0.18020 0.02811 0.16882 0.46896

##

## Coefficients:

## Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

## (Intercept) 0.87190 0.05860 14.88 <2e-16 ***

## x -1.69268 0.09359 -18.09 <2e-16 ***

## ---

## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

##

## Residual standard error: 0.232 on 98 degrees of freedom

## Multiple R-squared: 0.7695, Adjusted R-squared: 0.7671

## F-statistic: 327.1 on 1 and 98 DF, p-value: < 2.2e-16

# scatterplot is a quick alternative to

# plot(x, y)

# abline(coef = reg$coef, col = 3)

# But prediction is obviously problematic

car::scatterplot(y ~ x, col = 1, regLine = list(col = 2), smooth = FALSE)

Figure 2.18: Regression line for a dataset that clearly violates the linearity and homoscedasticity assumptions. The \(R^2\) is, nevertheless, as high as (approximately) \(0.77.\)

# Multiple linear model

# Create data that:

# 1) does not follow a linear model

# 2) the error is heteroscedastic

x1 <- seq(0.15, 1, l = 100)

set.seed(123456)

x2 <- runif(100, -3, 3)

eps <- rnorm(n = 100, sd = 0.25 * x1^2)

y <- 1 - 3 * x1 * (1 + 0.25 * sin(4 * pi * x1)) + 0.25 * cos(x2) + eps

# Great R^2!?

reg <- lm(y ~ x1 + x2)

summary(reg)

##

## Call:

## lm(formula = y ~ x1 + x2)

##

## Residuals:

## Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

## -0.78737 -0.20946 0.01031 0.19652 1.05351

##

## Coefficients:

## Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

## (Intercept) 0.788812 0.096418 8.181 1.1e-12 ***

## x1 -2.540073 0.154876 -16.401 < 2e-16 ***

## x2 0.002283 0.020954 0.109 0.913

## ---

## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

##

## Residual standard error: 0.3754 on 97 degrees of freedom

## Multiple R-squared: 0.744, Adjusted R-squared: 0.7388

## F-statistic: 141 on 2 and 97 DF, p-value: < 2.2e-16We can visualize the fit of the latter multiple linear model, since we are in \(p=2.\)

# But prediction is obviously problematic

car::scatter3d(y ~ x1 + x2, fit = "linear")

rgl::rglwidget()

The previous counterexamples illustrate that a large \(R^2\) means nothing in terms of inference if the assumptions of the model do not hold.

Remember that:

- \(R^2\) does not measure the correctness of a linear model but its usefulness, assuming the model is correct.

- \(R^2\) is the proportion of variance of \(Y\) explained by \(X_1,\ldots,X_p\) but, of course, only when the linear model is correct.

We finalize by pointing out a nice connection between the \(R^2,\) the ANOVA decomposition, and the least squares estimator \(\hat{\boldsymbol{\beta}}.\)

The ANOVA decomposition gives another view on the least-squares estimates: \(\hat{\boldsymbol{\beta}}\) are the estimated coefficients that maximize the \(R^2\) (among all the possible estimates we could think about). To see this, recall that

\[\begin{align*} R^2=\frac{\text{SSR}}{\text{SST}}=\frac{\text{SST} - \text{SSE}}{\text{SST}}=\frac{\text{SST} - \text{RSS}(\hat{\boldsymbol{\beta}})}{\text{SST}}. \end{align*}\]

Then, if \(\text{RSS}(\hat{\boldsymbol{\beta}})=\min_{\boldsymbol{\beta}\in\mathbb{R}^{p+1}}\text{RSS}(\boldsymbol{\beta}),\) then \(R^2\) is maximal for \(\hat{\boldsymbol{\beta}}.\)

2.7.2 The \(R^2\!{}_{\text{Adj}}\)

As we saw, these are equivalent forms for \(R^2\):

\[\begin{align} R^2=&\,\frac{\text{SSR}}{\text{SST}}=\frac{\text{SST}-\text{SSE}}{\text{SST}}=1-\frac{\text{SSE}}{\text{SST}}\nonumber\\ =&\,1-\frac{\hat\sigma^2}{\text{SST}}\times(n-p-1).\tag{2.23} \end{align}\]

The SSE on the numerator always decreases as more predictors are added to the model, even if these are not significant. As a consequence, the \(R^2\) always increases with \(p\). Why is this so? Intuitively, because the complexity – hence the flexibility – of the model increases when we use more predictors to explain \(Y.\) Mathematically, because when \(p\) approaches \(n-1\) the second term in (2.23) is reduced and, as a consequence, \(R^2\) grows.

The adjusted \(R^2\), \(R^2_\text{Adj},\) is an important quantity specifically designed to overcome this \(R^2\)’s flaw, ubiquitous in multiple linear regression. The purpose is to have a better tool for comparing models without systematically favoring more complex models.48 This alternative coefficient is defined as

\[\begin{align} R^2_{\text{Adj}}:=&\,1-\frac{\text{SSE}/(n-p-1)}{\text{SST}/(n-1)}=1-\frac{\text{SSE}}{\text{SST}}\times\frac{n-1}{n-p-1}\nonumber\\ =&\,1-\frac{\hat\sigma^2}{\text{SST}}\times (n-1).\tag{2.24} \end{align}\]

The \(R^2_{\text{Adj}}\) is independent of \(p,\) at least explicitly. If \(p=1\) then \(R^2_{\text{Adj}}\) is almost \(R^2\) (practically identical if \(n\) is large). Both (2.23) and (2.24) are quite similar except for the last factor, which in the latter does not depend on \(p.\) Therefore, (2.24) will only increase if \(\hat\sigma^2\) is reduced with \(p;\) in other words, if the new variables contribute in the reduction of variability around the regression plane.

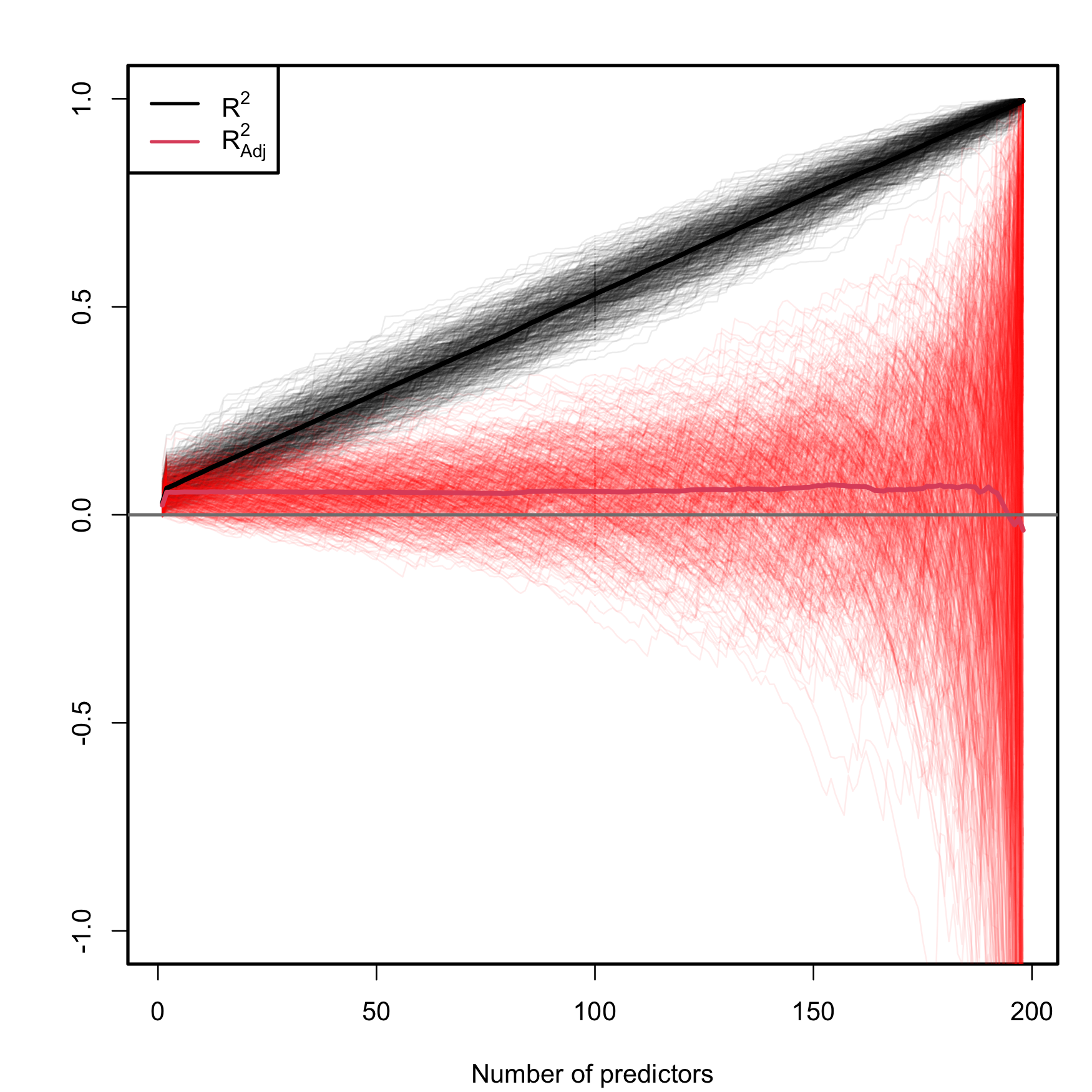

The different behavior between \(R^2\) and \(R^2_\text{Adj}\) can be visualized with the following simulation study. Suppose that we generate a random dataset \(\{(X_{i1},X_{i2},Y_i)\}_{i=1}^n,\) with \(n=200\) observations of two predictors \(X_1\) and \(X_2\) that are distributed as a \(\mathcal{N}(0,1),\) and a response \(Y\) generated by the linear model

\[\begin{align} Y_i=\beta_0+\beta_1X_{i1}+\beta_2X_{i2}+\varepsilon_i,\tag{2.25} \end{align}\]

where \(\varepsilon_i\sim\mathcal{N}(0,9).\) To this data, we add \(196\) “garbage” predictors \(X_j\sim\mathcal{N}(0,1)\) that are completely independent from \(Y.\) Therefore, we end up with \(p=198\) predictors where only the first two ones are relevant for explaining \(Y.\) We compute now the \(R^2(j)\) and \(R^2_\text{Adj}(j)\) for the models

\[\begin{align} Y=\beta_0+\beta_1X_{1}+\cdots+\beta_jX_{j}+\varepsilon,\tag{2.26} \end{align}\]

with \(j=1,\ldots,p,\) and we plot them as the curves \((j,R^2(j))\) and \((j,R_\text{Adj}^2(j)).\) Since \(R^2\) and \(R^2_\text{Adj}\) are random variables, we repeat this procedure \(M=500\) times to have an idea of the variability behind \(R^2\) and \(R^2_\text{Adj}.\) Figure 2.19 contains the results of this experiment.

Figure 2.19: Comparison of \(R^2\) and \(R^2_{\text{Adj}}\) on the model (2.26) fitted with data generated by (2.25). The number of predictors \(p\) ranges from \(1\) to \(198,\) with only the first two predictors being significant. The \(M=500\) curves for each color arise from \(M\) simulated datasets of sample size \(n=200.\) The thicker curves are the mean of each color’s curves.

As it can be seen, the \(R^2\) increases linearly with the number of predictors considered, although only the first two ones were actually relevant. Thus, if we did not know about the random mechanism (2.25) that generated \(Y,\) we would be tempted to believe that the more adequate models would be the ones with a larger number of predictors. On the contrary, \(R^2_\text{Adj}\) only increases in the first two variables and then exhibits a mild decaying trend, indicating that, on average, the best choice for the number of predictors is actually close to \(p=2.\) However, note that \(R^2_\text{Adj}\) has a huge variability when \(p\) approaches \(n-2,\) a consequence of the explosive variance of \(\hat\sigma^2\) in that degenerate case49. The experiment helps to visualize that \(R^2_\text{Adj}\) is more adequate than the \(R^2\) for evaluating the fit of a multiple linear regression50.

An example of a simulated dataset considered in the experiment of Figure 2.19 is:

# Generate data

p <- 198

n <- 200

set.seed(3456732)

beta <- c(0.5, -0.5, rep(0, p - 2))

X <- matrix(rnorm(n * p), nrow = n, ncol = p)

Y <- drop(X %*% beta + rnorm(n, sd = 3))

data <- data.frame(y = Y, x = X)

# Regression on the two meaningful predictors

summary(lm(y ~ x.1 + x.2, data = data))

# Adding 20 "garbage" variables

# R^2 increases and adjusted R^2 decreases

summary(lm(y ~ X[, 1:22], data = data))The \(R^2_\text{Adj}\) no longer measures the proportion of variation of \(Y\) explained by the regression, but the result of correcting this proportion by the number of predictors employed. As a consequence of this, \(R^2_\text{Adj}\leq1\) and \(R^2_\text{Adj}\) can be negative.

The next code illustrates a situation where we have two predictors completely independent from the response. The fitted model has a negative \(R^2_\text{Adj}.\)

# Three independent variables

set.seed(234599)

x1 <- rnorm(100)

x2 <- rnorm(100)

y <- 1 + rnorm(100)

# Negative adjusted R^2

summary(lm(y ~ x1 + x2))

##

## Call:

## lm(formula = y ~ x1 + x2)

##

## Residuals:

## Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

## -3.5081 -0.5021 -0.0191 0.5286 2.4750

##

## Coefficients:

## Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

## (Intercept) 0.97024 0.10399 9.330 3.75e-15 ***

## x1 0.09003 0.10300 0.874 0.384

## x2 -0.05253 0.11090 -0.474 0.637

## ---

## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

##

## Residual standard error: 1.034 on 97 degrees of freedom

## Multiple R-squared: 0.009797, Adjusted R-squared: -0.01062

## F-statistic: 0.4799 on 2 and 97 DF, p-value: 0.6203

For the previous example, construct more predictors (x3,

x4, …) that are independent from y. Then check

that, when the predictors are added to the model, the \(R^2_\text{Adj}\) decreases and the \(R^2\) increases.

Beware of the \(R^2\) and \(R^2_\text{Adj}\) for model fits with

no intercept! If the linear model is fitted with no

intercept, the summary function silently

returns a ‘Multiple R-squared’ and an

‘Adjusted R-squared’ that do not correspond (see

this

question in the R FAQ) with the seen expressions

\[\begin{align*} R^2=1-\frac{\text{SSE}}{\sum_{i=1}^n(Y_i-\bar{Y})^2},\quad R^2_{\text{Adj}}=1-\frac{\text{SSE}}{\text{SST}}\times\frac{n-1}{n-p-1}. \end{align*}\]

In the case with no intercept, summary rather

returns

\[\begin{align*} R^2_0 :=1-\frac{\text{SSE}}{\sum_{i=1}^nY_i^2},\quad R^2_{0,\text{Adj}} :=1-\frac{\text{SSE}}{\sum_{i=1}^nY_i^2}\times\frac{n-1}{n-p-1}. \end{align*}\]

The reason is perhaps shocking: if the model is fitted without intercept and neither the response nor the predictors are centered, then the ANOVA decomposition does not hold, in the sense that

\[\begin{align*} \mathrm{SST} \neq \mathrm{SSR} + \mathrm{SSE}. \end{align*}\]

The fact that the ANOVA decomposition does not hold for no-intercept models has serious consequences on the theory we built. In particular, the \(R^2\) can be negative and \(R^2\neq r^2_{y\hat y},\) both deriving from the fact that \(\sum_{i=1}^n\hat\varepsilon_i\neq0.\) Therefore, the \(R^2\) cannot be regarded as the “proportion of variance explained” if the model fit is performed without intercept. The \(R^2_0\) and \(R^2_{0,\text{Adj}}\) versions are considered because they are the ones that arise from the “no-intercept ANOVA decomposition”

\[\begin{align*} \mathrm{SST}_0 = \mathrm{SSR}_0 + \mathrm{SSE},\quad \mathrm{SST}_0:=\sum_{i=1}^nY_i^2,\quad \mathrm{SSR}_0:=\sum_{i=1}^n\hat{Y}_i^2. \end{align*}\]

and therefore the \(R^2_0\) is guaranteed to be a quantity in \([0,1].\) It would indeed be the proportion of variance explained if the predictors and the response were centered (i.e., if \(\bar Y=0\) and \(\bar X_j=0,\) \(j=1,\ldots,p\)).

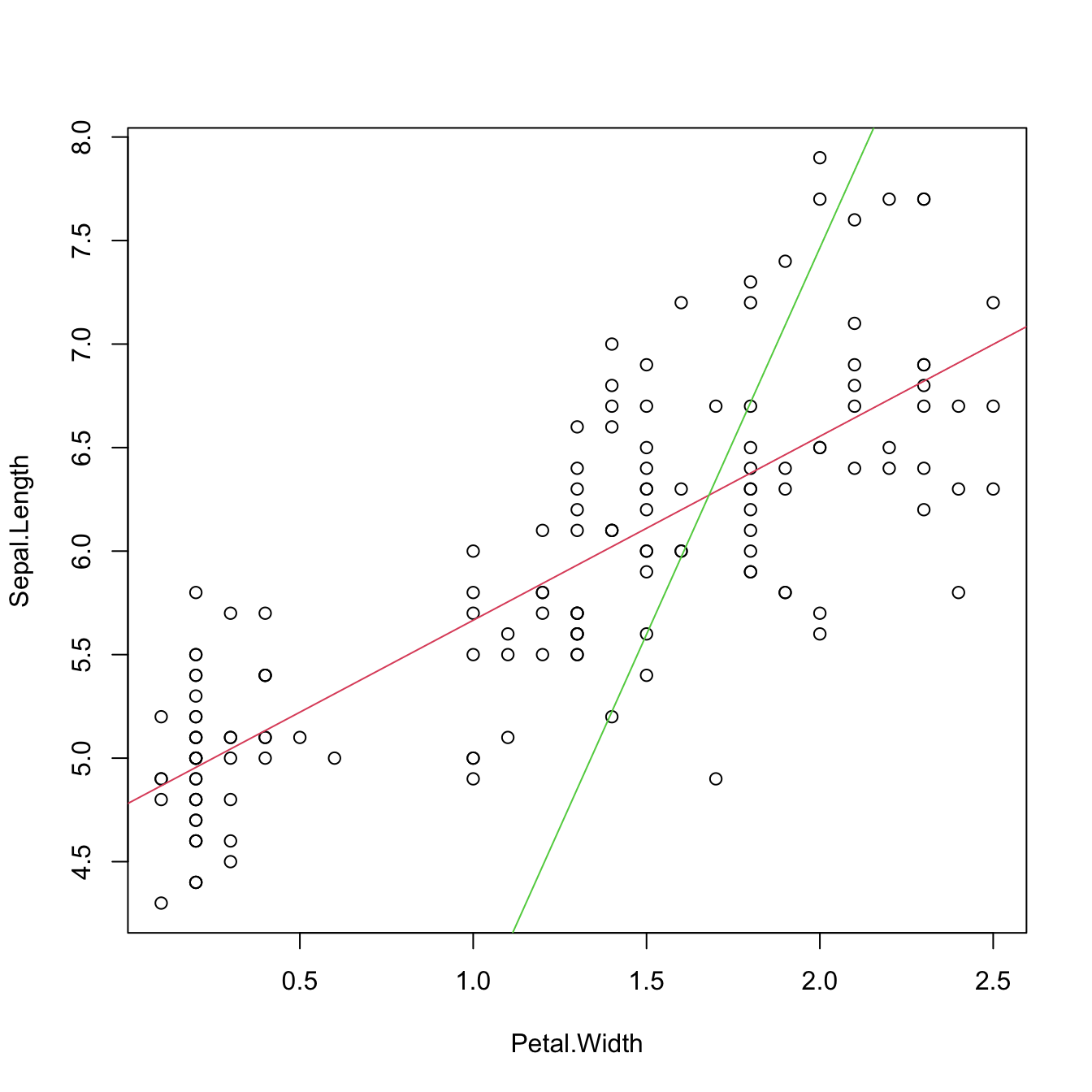

The next chunk of code illustrates these concepts for the iris dataset.

# Model with intercept

mod1 <- lm(Sepal.Length ~ Petal.Width, data = iris)

mod1

##

## Call:

## lm(formula = Sepal.Length ~ Petal.Width, data = iris)

##

## Coefficients:

## (Intercept) Petal.Width

## 4.7776 0.8886

# Model without intercept

mod0 <- lm(Sepal.Length ~ 0 + Petal.Width, data = iris)

mod0

##

## Call:

## lm(formula = Sepal.Length ~ 0 + Petal.Width, data = iris)

##

## Coefficients:

## Petal.Width

## 3.731

# Recall the different way of obtaining the estimators

X1 <- cbind(1, iris$Petal.Width)

X0 <- cbind(iris$Petal.Width) # No column of ones!

Y <- iris$Sepal.Length

betaHat1 <- solve(crossprod(X1)) %*% t(X1) %*% Y

betaHat0 <- solve(crossprod(X0)) %*% t(X0) %*% Y

betaHat1

## [,1]

## [1,] 4.7776294

## [2,] 0.8885803

betaHat0

## [,1]

## [1,] 3.731485

# Summaries: higher R^2 for the model with no intercept!?

summary(mod1)

##

## Call:

## lm(formula = Sepal.Length ~ Petal.Width, data = iris)

##

## Residuals:

## Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

## -1.38822 -0.29358 -0.04393 0.26429 1.34521

##

## Coefficients:

## Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

## (Intercept) 4.77763 0.07293 65.51 <2e-16 ***

## Petal.Width 0.88858 0.05137 17.30 <2e-16 ***

## ---

## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

##

## Residual standard error: 0.478 on 148 degrees of freedom

## Multiple R-squared: 0.669, Adjusted R-squared: 0.6668

## F-statistic: 299.2 on 1 and 148 DF, p-value: < 2.2e-16

summary(mod0)

##

## Call:

## lm(formula = Sepal.Length ~ 0 + Petal.Width, data = iris)

##

## Residuals:

## Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

## -3.1556 -0.3917 1.0625 3.8537 5.0537

##

## Coefficients:

## Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

## Petal.Width 3.732 0.150 24.87 <2e-16 ***

## ---

## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

##

## Residual standard error: 2.609 on 149 degrees of freedom

## Multiple R-squared: 0.8058, Adjusted R-squared: 0.8045

## F-statistic: 618.4 on 1 and 149 DF, p-value: < 2.2e-16

# Wait a moment... let's see the actual fit

plot(Sepal.Length ~ Petal.Width, data = iris)

abline(mod1, col = 2) # Obviously, much better

abline(mod0, col = 3)

# Compute the R^2 manually for mod1

SSE1 <- sum(mod1$residuals^2)

SST1 <- sum((mod1$model$Sepal.Length - mean(mod1$model$Sepal.Length))^2)

1 - SSE1 / SST1

## [1] 0.6690277

# Compute the R^2 manually for mod0

SSE0 <- sum(mod0$residuals^2)

SST0 <- sum((mod0$model$Sepal.Length - mean(mod0$model$Sepal.Length))^2)

1 - SSE0 / SST0

## [1] -8.926872

# It is negative!

# Recall that the mean of the residuals is not zero!

mean(mod0$residuals)

## [1] 1.368038

# What summary really returns if there is no intercept

n <- nrow(iris)

p <- 1

R0 <- 1 - sum(mod0$residuals^2) / sum(mod0$model$Sepal.Length^2)

R0Adj <- 1 - sum(mod0$residuals^2) / sum(mod0$model$Sepal.Length^2) *

(n - 1) / (n - p - 1)

R0

## [1] 0.8058497

R0Adj

## [1] 0.8045379

# What if we centered the data previously?

irisCen <- data.frame(scale(iris[, -5], center = TRUE, scale = FALSE))

modCen1 <- lm(Sepal.Length ~ Petal.Width, data = irisCen)

modCen0 <- lm(Sepal.Length ~ 0 + Petal.Width, data = irisCen)

# No problem, "correct" R^2

summary(modCen1)

##

## Call:

## lm(formula = Sepal.Length ~ Petal.Width, data = irisCen)

##

## Residuals:

## Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

## -1.38822 -0.29358 -0.04393 0.26429 1.34521

##

## Coefficients:

## Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

## (Intercept) -9.050e-16 3.903e-02 0.0 1

## Petal.Width 8.886e-01 5.137e-02 17.3 <2e-16 ***

## ---

## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

##

## Residual standard error: 0.478 on 148 degrees of freedom

## Multiple R-squared: 0.669, Adjusted R-squared: 0.6668

## F-statistic: 299.2 on 1 and 148 DF, p-value: < 2.2e-16

summary(modCen0)

##

## Call:

## lm(formula = Sepal.Length ~ 0 + Petal.Width, data = irisCen)

##

## Residuals:

## Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

## -1.38822 -0.29358 -0.04393 0.26429 1.34521

##

## Coefficients:

## Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

## Petal.Width 0.8886 0.0512 17.36 <2e-16 ***

## ---

## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

##

## Residual standard error: 0.4764 on 149 degrees of freedom

## Multiple R-squared: 0.669, Adjusted R-squared: 0.6668

## F-statistic: 301.2 on 1 and 149 DF, p-value: < 2.2e-16

# But only if we center predictor and response...

summary(lm(iris$Sepal.Length ~ 0 + irisCen$Petal.Width))

##

## Call:

## lm(formula = iris$Sepal.Length ~ 0 + irisCen$Petal.Width)

##

## Residuals:

## Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

## 4.455 5.550 5.799 6.108 7.189

##

## Coefficients:

## Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

## irisCen$Petal.Width 0.8886 0.6322 1.406 0.162

##

## Residual standard error: 5.882 on 149 degrees of freedom

## Multiple R-squared: 0.01308, Adjusted R-squared: 0.006461

## F-statistic: 1.975 on 1 and 149 DF, p-value: 0.1619Let’s play the evil practitioner and try to modify the \(R_0^2\) returned by summary when the intercept is excluded. If we were really evil, we could use this knowledge to fool someone that is not aware of the difference between \(R_0^2\) and \(R^2\) into believing that any given model is incredibly good or bad in terms of the \(R^2\)!

- For the previous example, display the \(R_0^2\) as a function of a shift in mean of the predictor

Petal.Width. What can you conclude? Hint: you may useI()for performing the shifting inside the model equation. - What shift on

Petal.Widthwould be necessary to achieve an \(R_0^2\approx0.95\)? Is this shift unique? - Do the same but for a shift in the mean of the response

Sepal.Length. What shift would be necessary to achieve an \(R_0^2\approx0.50\)? Is there a single shift? - Consider the multiple linear model

medv ~ nox + rmfor theBostondataset. We want to tweak the \(R_0^2\) to set it to any number in \([0,1].\) Can we achieve this by only shiftingrmormedv(only one of them)? - Explore systematically the \(R_0^2\) for the shifting combinations of

rmandmedvand obtain a combination that delivers an \(R_0^2\approx 0.30.\) Hint: usefilled.contour()for visualizing the \(R_0^2\) surface.

2.7.3 Case study application

Coming back to the case study, we have studied so far three models:

# Fit models

modWine1 <- lm(Price ~ ., data = wine)

modWine2 <- lm(Price ~ . - FrancePop, data = wine)

modWine3 <- lm(Price ~ Age + WinterRain, data = wine)

# Summaries

summary(modWine1)

##

## Call:

## lm(formula = Price ~ ., data = wine)

##

## Residuals:

## Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

## -0.46541 -0.24133 0.00413 0.18974 0.52495

##

## Coefficients:

## Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

## (Intercept) -2.343e+00 7.697e+00 -0.304 0.76384

## WinterRain 1.153e-03 4.991e-04 2.311 0.03109 *

## AGST 6.144e-01 9.799e-02 6.270 3.22e-06 ***

## HarvestRain -3.837e-03 8.366e-04 -4.587 0.00016 ***

## Age 1.377e-02 5.821e-02 0.237 0.81531

## FrancePop -2.213e-05 1.268e-04 -0.175 0.86313

## ---

## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

##

## Residual standard error: 0.293 on 21 degrees of freedom

## Multiple R-squared: 0.8278, Adjusted R-squared: 0.7868

## F-statistic: 20.19 on 5 and 21 DF, p-value: 2.232e-07

summary(modWine2)

##

## Call:

## lm(formula = Price ~ . - FrancePop, data = wine)

##

## Residuals:

## Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

## -0.46024 -0.23862 0.01347 0.18601 0.53443

##

## Coefficients:

## Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

## (Intercept) -3.6515703 1.6880876 -2.163 0.04167 *

## WinterRain 0.0011667 0.0004820 2.420 0.02421 *

## AGST 0.6163916 0.0951747 6.476 1.63e-06 ***

## HarvestRain -0.0038606 0.0008075 -4.781 8.97e-05 ***

## Age 0.0238480 0.0071667 3.328 0.00305 **

## ---

## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

##

## Residual standard error: 0.2865 on 22 degrees of freedom

## Multiple R-squared: 0.8275, Adjusted R-squared: 0.7962

## F-statistic: 26.39 on 4 and 22 DF, p-value: 4.057e-08

summary(modWine3)

##

## Call:

## lm(formula = Price ~ Age + WinterRain, data = wine)

##

## Residuals:

## Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

## -0.88964 -0.51421 -0.00066 0.43103 1.06897

##

## Coefficients:

## Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

## (Intercept) 5.9830427 0.5993667 9.982 5.09e-10 ***

## Age 0.0360559 0.0137377 2.625 0.0149 *

## WinterRain 0.0007813 0.0008780 0.890 0.3824

## ---

## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

##

## Residual standard error: 0.5769 on 24 degrees of freedom

## Multiple R-squared: 0.2371, Adjusted R-squared: 0.1736

## F-statistic: 3.73 on 2 and 24 DF, p-value: 0.03884The model modWine2 has the largest \(R^2_\text{Adj}\) among the three studied. It is a model that explains the \(82.75\%\) of the variability in a non-redundant way and with all its coefficients significant. Therefore, we have a formula for effectively explaining and predicting the quality of a vintage (answers Q1). Prediction and, importantly, quantification of the uncertainty in the prediction, can be done through the predict function.

Furthermore, the interpretation of modWine2 agrees with well-known facts in viticulture that make perfect sense. Precisely (answers Q2):

- Higher temperatures are associated with better quality (higher priced) wine.

- Rain before the growing season is good for the wine quality, but during harvest is bad.

- The quality of the wine improves with the age.

Although these conclusions could be regarded as common folklore, keep in mind that this model

- allows to quantify the effect of each variable on the wine quality and

- provides a precise way of predicting the quality of future vintages.

Which is not the \(\hat\sigma^2\) in (2.21), but \(\hat\sigma^2\) is obviously dependent on \(\sigma^2.\)↩︎

Which do not hold!↩︎

An informal way of regarding the difference between \(R^2\) and \(R^2_\text{Adj}\) is by thinking of \(R^2\) as a measure of fit that “is not aware of the dangers of overfitting”. In this interpretation, \(R^2_\text{Adj}\) is the overfitting-aware version of \(R^2.\)↩︎

This indicates that \(R^2_\text{Adj}\) can act as a model selection device up to a certain point, as its effectiveness becomes too variable, too erratic, when the number of predictors is very high in comparison with \(n.\)↩︎

Coincidentally, the experiment also serves as a reminder about the randomness of \(R^2\) and \(R^2_{\text{Adj}},\) a fact that is sometimes overlooked.↩︎