1.7 Depressions in practice

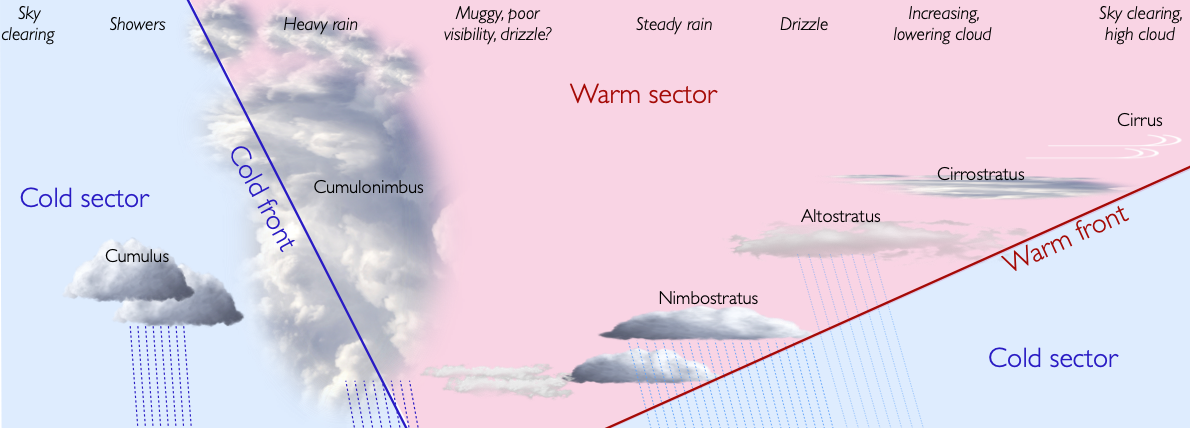

The centers of most depressions pass to the north of the UK. As a depression goes overhead, we hence generally pass under the warm front, the warm sector and the cold front. Remember that warm air is rising up along both of the fronts. Warm air rising leads to clouds and potentially rain. This should lead to a somewhat predictable sequence of weather, as shown in the diagram below.

The first sign of the approaching depression is moist air rising high at the front edge of the warm front, causing ice crystals to be blown eastwards by the jet stream. These can be seen as clouds called cirrus, or ‘mares tails’:

As the warm front becomes lower overhead, the high cloud develops into a thin layer known as cirrostratus:

This cloud produces a halo around the sun or moon.

As the front comes lower still, layers of cloud form at mid levels, known as altostratus:

These clouds thicken and lower as the warm front draws near, eventually producing persistent rain near the warm front from featureless grey nimbostratus clouds:

Within the warm sector, humid damp air will bring poor visibility and intermittent rain or drizzle. Fog and mist is possible. However, as the depression tracks east, this weather may improve to give clear spells.

The arrival of the cold front is heralded by thicker clouds and heavier rain. The wind will tend to be gusty and there may be thunderclouds.

Behind the front, the sky should clear rapidly. It may be followed by cumulonimbus clouds that bring sharp showers. In practice, depressions rarely have the perfect form and weather sequence described. However, the sequence of events described above is a useful guide.