4.8 Navigational marks*

To assist the navigation of ships, navigational marks such as lighthouses, buoys and beacons are placed around the coastline. Because kayaks can operate in very shallow water, these aren’t useful to us in the way that they were intended for large vessels. However, they do provide useful landmarks if you’re carrying the nautical chart. A basic understanding of what the main buoys mean will help you understand where larger vessels are likely to go and thus help you avoid them.

Lateral marks are used to mark the edges of shipping channels – for example into and out of a harbor. As a big ship enters a harbor, red can-shaped port-hand buoys will be on the left, whilst green conical starboard-hand buoys will be on the right.

A mnemonic to remember this is “no more cans of red port left”.

This is the system known as ‘IALA A’, used in the UK and many other parts of the world. Some areas, notably the US, use ‘IALA B’, in which the colors of the buoys, but not the shapes, are reversed.

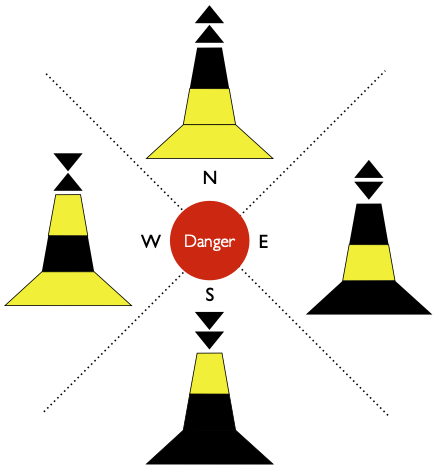

Cardinal marks indicate the presence of hazards – normally shallows that big vessels would rather avoid. A cardinal mark indicates the direction from the mark in which safe water can be found. For example, safe deep water will be found to the north of a north cardinal buoy, with the hazard lying to the south. The marks are differentiated by the orientation of two cones at the top as well as the sequence of black and yellow colors on the buoy, as shown in the diagram.

Because cardinal marks indicate shallow areas, they can sometimes be posts attached to the seabed rather than floating buoys.

The buoy in the image below is an west cardinal mark, indicating shallows to the east.

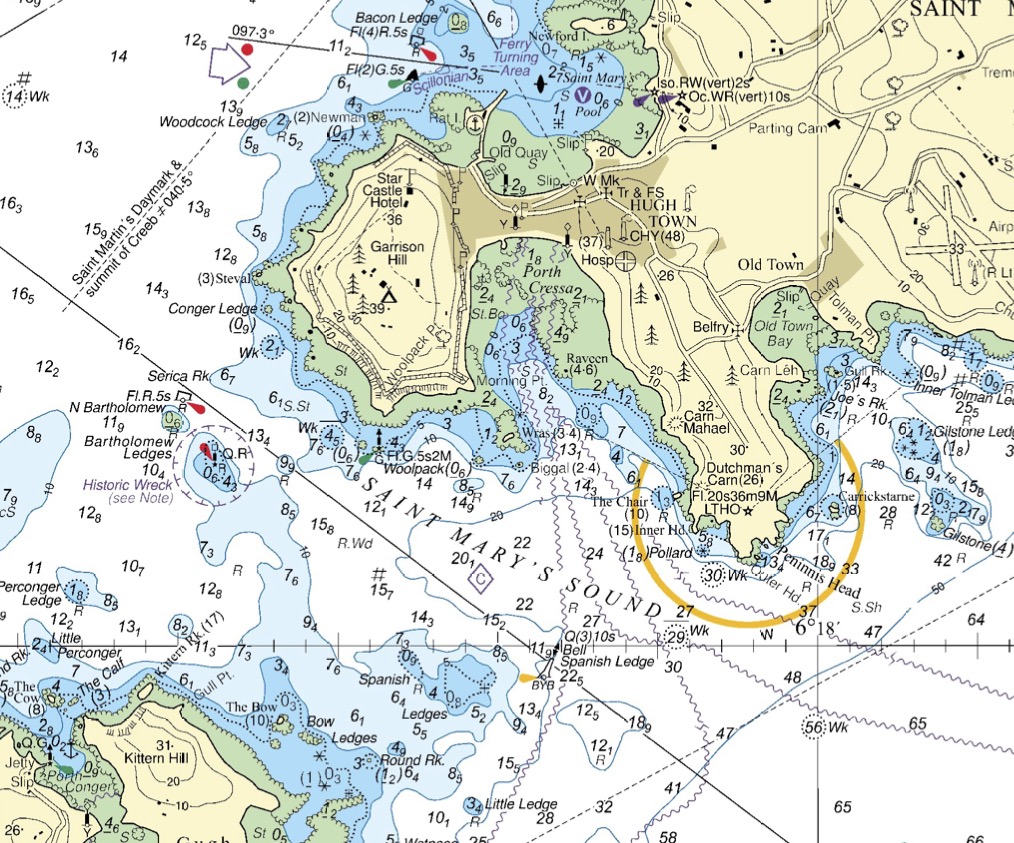

The chart extract below shows an example of how navigational marks might be positioned:

As sea kayakers, the hazards (e.g. shallows) indicated by lateral and cardinal buoys aren’t an issue for us. It’s often better to go the ‘wrong’ side to keep out the way of big vessels.

For example, imagine that we’re crossing Saint Mary’s Sound (see chart above) from Kittern Rock to the western corner of Garrison Hill. We’ll use bearings and transits to keep on course, but the red post and buoy that mark the Bartholomew ledges will be useful landmarks along our way.

As we get close to the post and buoy, we notice the ‘Scillonian’ - a 68 meter long ferry - coming around the headland of Garrison Hill. It looks like it’ll head to our right.

However, consulting the chart, we notice that the main shipping channel passes to the north-east of the Bartholomew ledges buoy - we can see the course marked with a line on the chart, and we know that the channel must go between the red Bartholomew ledges buoy and the green ‘Woolpack’ mark.

It is possible, but unlikely, that the ferry will go the south-west of the Bartholomew ledges. However, it certainly won’t go through the middle of the very shallow ledges marked by the red buoy and post. The safest place to be is close to these lateral marks - ideally between the N Bartholomew buoy and the post.

So, we paddle the short distance across to the N Bartholomew buoy and pause our crossing, taking advantage of a slight eddy forming over the shallows so we don’t need to paddle too hard into the tidal stream to hold our position. We watch the Scillonian turn. For a scary moment it points directly towards us, but it keeps turning, and soon passes to the east of us.

Chart © Crown Copyright and/or database rights. NOT FOR NAVIGATION. Reproduced by permission of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office and the UK Hydrographic Office (www.GOV.uk/UKHO)