1.5 Some meteorology*

It’s not essential by any means to understand the science of what drives the weather to have a safe and enjoyable time on the sea. However, it does help to bring some of the other information here together. And being able to relate what you’re seeing in the sky to the forecast and the science of the atmosphere can be fascinating.

1.5.1 Air masses

Although a decent forecast is all that is really necessary to plan a day’s sea kayaking, some knowledge of the science behind the weather can help you understand what is going on and put the weather that you observe from your kayak into context.

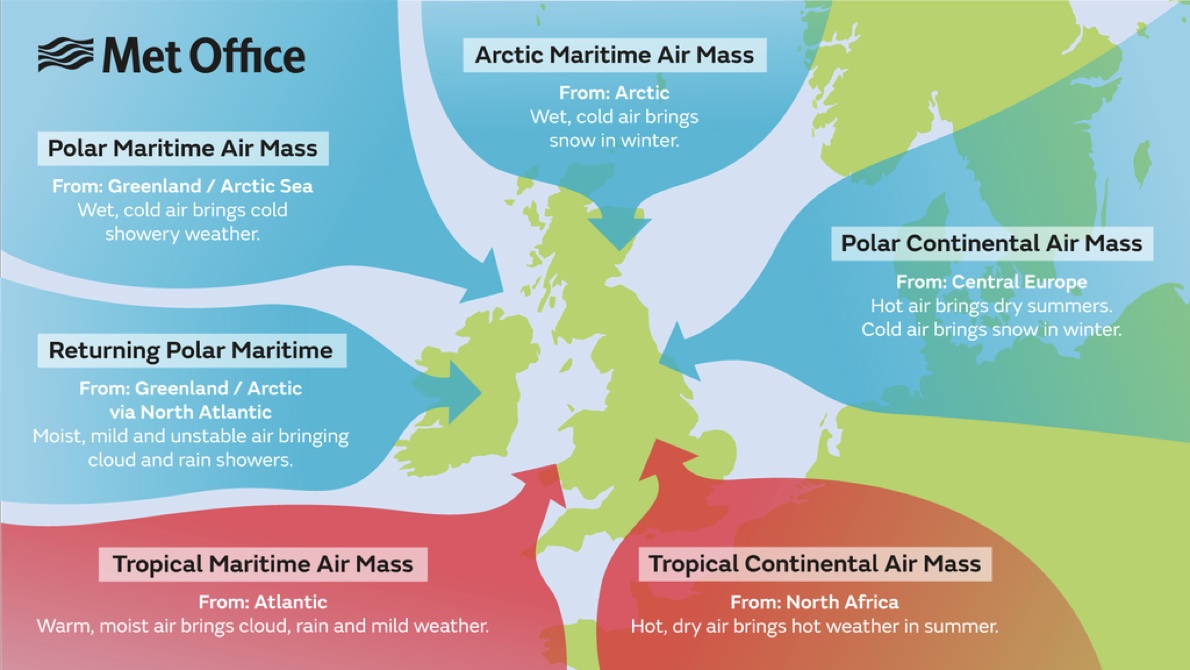

Let’s begin by thinking about how the earth’s surface affects the air above it. Air that spends time over cold land cools and becomes fairly dry. Over a warm sea, the air will be heated and become moist. Depending on the wind direction, air that has spent time over other parts of the world can blow over the UK. The diagram below shows these air masses and the wind directions that bring them to us:

Air masses move, but when they meet they tend not to mix well. Instead, there are sharp divisions between them known as fronts.

Warm air tends to rise. As air rises, it cools and any water vapour that it is carrying will form clouds and potentially rain. The condensation of water vapour makes more heat available, such that wet air tends to rise further and faster than dry air.

What might cause air to rise? The air masses shown above are fairly homogenous, so there will be little tendency for air to move vertically. There are two key processes that cause air to rise, forming clouds and potentially rain:

Being pushed up by another air mass at a front - more of this later.

Being heated by the warm earth below, which in turn is being warmed by the sun. This is the process by which white puffy cumulus clouds develop on sunny days and how they can eventually develop into violent thunderstorms in the afternoon.

1.5.2 Global circulation

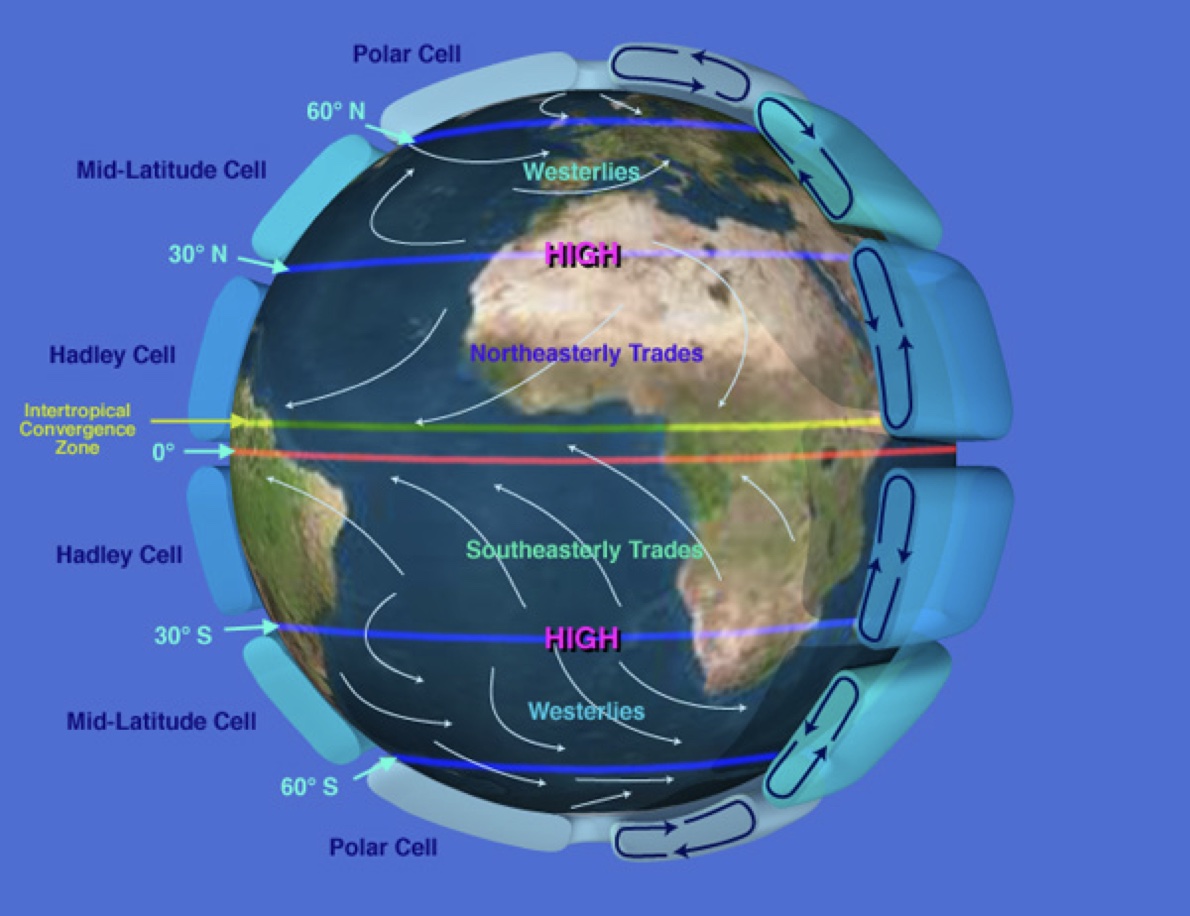

The sun heats the earth most at the equator and least over the poles. At the equator, the heated air rises and at the poles it sinks. Rather than a single convection cell stretching from equator to pole, the atmosphere actually has 3 convection cells in each hemisphere.

The UK is situated close to the boundary between the Polar Cell and the Mid-Latitude cell. The cold air to the north and the warmer air to the south tend not to mix. They interface at a boundary known as the polar front. This boundary moves around, tending to be further south in the winter and further north in the summer.

Very fast high level winds form above the polar front. These winds, known as the jet stream, blow from west to east. At lower levels, winds tend to blow from the west in the mid-latitude cell and from the east in the polar cell.

Disturbances along the polar front cause the warm air from the mid-latitude cell to intrude into the colder air mass to the north. This sets up the conditions for the formation of an area of low pressure, or a depression. We’ll look at these in some detail, as they are responsible for much of the UK’s bad weather.

1.5.3 Depressions

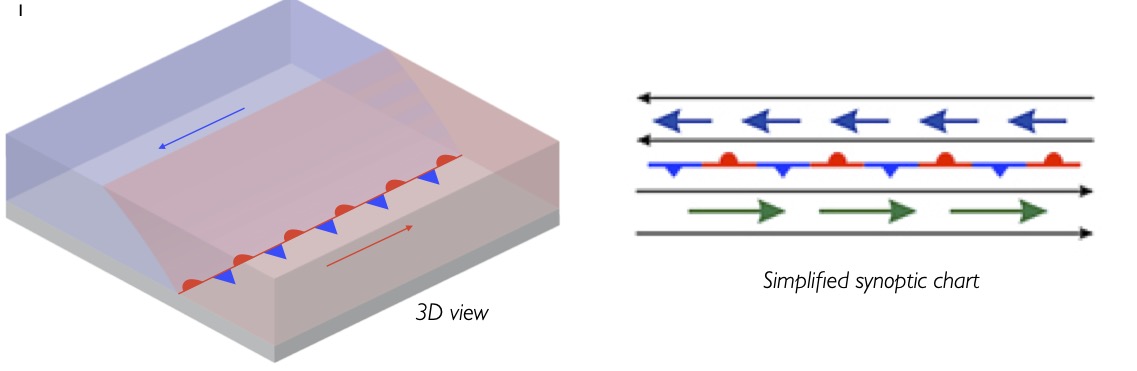

Understanding depressions requires an appreciation for the 3-dimensional structure of the atmosphere. However, on synoptic weather charts, we only see the isobars (lines of equal pressure) and fronts as they are at the surface of the earth. In this description, 3D illustrations are shown next to a schematic of a synoptic chart.

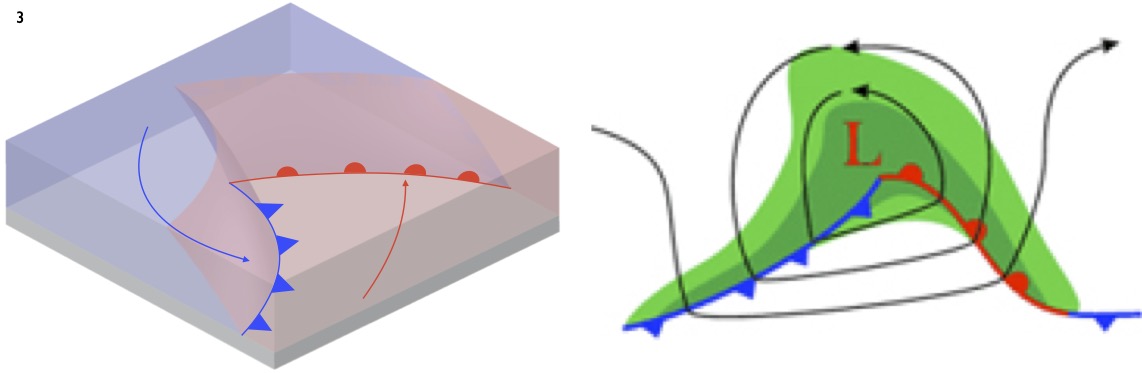

We begin by taking a closer look at the polar front - the boundary between the cold air coming from the Arctic and the warmer air from the south. Because the warm air mass is less dense than the colder one, the front is not vertical - the warm air mass tends to lie over the colder.

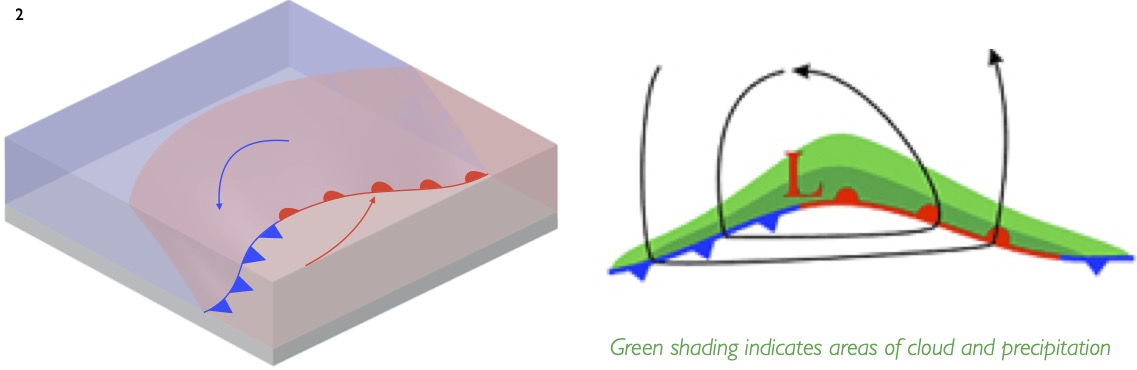

The polar front is not a very stable situation - the warm air can tend to float over the cooler, and the jet stream wind blowing above can draw air in and up. Disturbances along the polar front cause the warm air from the mid-latitude cell to intrude into the colder air mass to the north.The rising air causes a reduction in surface pressure, causing wind. The low pressure draws in more warm air from the south, causing the area of low pressure to deepen. Because the earth is rotating, air does not blow directly in towards low pressure areas, but instead spirals in anticlockwise, rather like water down a plughole.

These processes become self-sustaining.The warm air rises, creating low pressure, drawing in yet more warm and wet air from the south. Pressure drops and a circulation of wind starts to develop around the disturbance in the polar front. At this stage the depression is known as an early-stage or wave-type low.

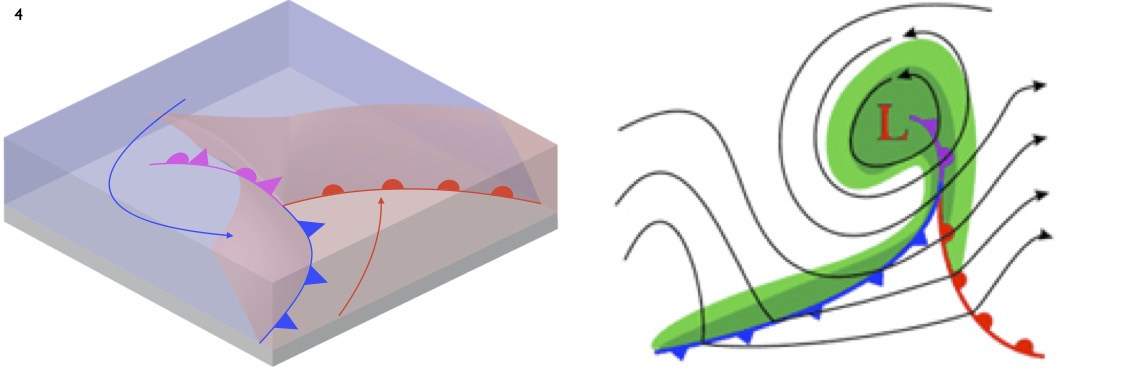

As the low develops, a wedge shaped area of warm air, known as the warm sector, develops. The depression is now fully developed, and significant winds are now blowing anticlockwise around the low pressure area.The boundaries between the warm sector and the colder air are known as ‘fronts’ and are named after the air behind them.The ‘warm front’ at the front of the warm sector has warm air behind, whilst the ‘cold front’ at the back has cold air behind it. Warm fronts are depicted with semicircles and sometimes shown in red. Cold fronts are marked by triangles and shown in blue

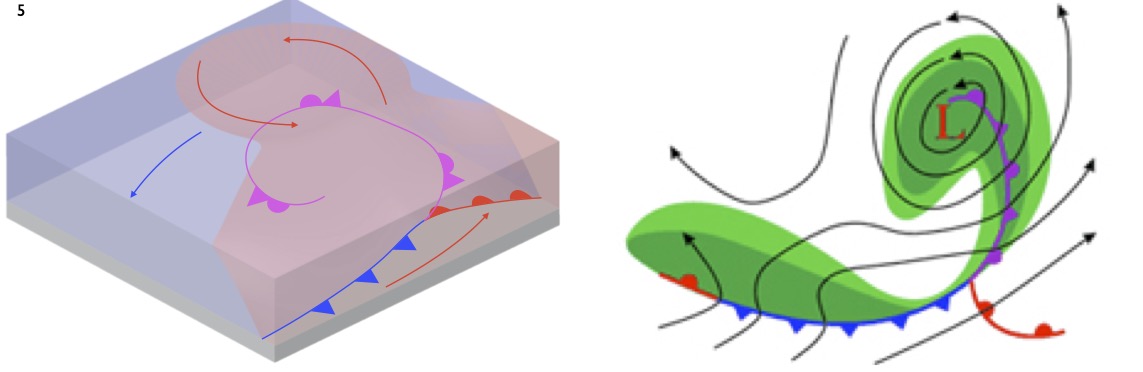

Further movement of the warm sector over the cold air mass causes some of the warm air to be lifted entirely off the ground.This is know as ‘occlusion’. On synoptic charts, an occluded front is drawn under this elevated warm air. It is marked with both semicircles and triangles and sometimes shown in purple. Once occlusion occurs, the depression will typically not reduce in pressure much further.

As occlusion continues,the system is cut off from the supply of further warm air and moisture from the south. As such, the depression cannot develop further and now starts to dissipate.

Synoptic diagrams from the COMET® Website at http://meted.ucar.edu/ of the University Corporation for Atmospheric Research (UCAR), sponsored in part through cooperative agreement(s) with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), U.S. Department of Commerce (DOC). ©1997-2016 University Corporation for Atmospheric Research. All Rights Reserved.

1.5.4 Depressions in practice

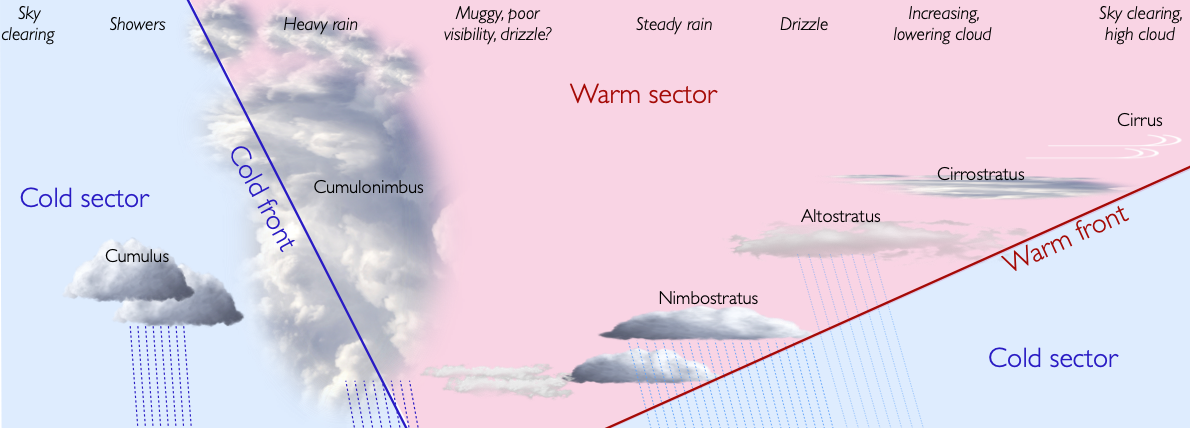

The centers of most depressions pass to the north of the UK. As a depression goes overhead, we hence generally pass under the warm front, the warm sector and the cold front. Remember that warm air is rising up along both of the fronts. Warm air rising leads to clouds and potentially rain. This should lead to a somewhat predictable sequence of weather, as shown in the diagram below.

For more information on the cloud types described here, see the notes on clouds in the ‘Environmental clues’ section.

The first sign of the approaching depression is moist air rising high at the front edge of the warm front, causing ice crystals to be blown eastwards by the jet stream. These can be seen as high wispy cirrus, or ‘mares tails’. As the warm front becomes lower overhead, the high cloud develops into a thin layer known as cirrostratus. This cloud produces a halo around the sun or moon.

As the front comes lower still, layers of cloud form at mid levels, known as altostratus.

These clouds thicken and lower as the warm front draws near, eventually producing persistent rain near the warm front from featureless grey nimbostratus clouds.

Within the warm sector, humid damp air will bring poor visibility and intermittent rain or drizzle. Fog and mist is possible. However, as the depression tracks east, this weather may improve to give clear spells.

The arrival of the cold front is heralded by thicker clouds and heavier rain. The wind will tend to be gusty and there may be thunderclouds.

Behind the front, the sky should clear rapidly. It may be followed by cumulonimbus clouds that bring sharp showers. In practice, depressions rarely have the perfect form and weather sequence described. However, the sequence of events described above is a useful guide.