1.2 Wind

1.2.1 Wind strength

It is important to be able to understand the effect that the wind will have on us as sea kayakers.

The wind speed given in a forecast is the predicted wind speed at 10 meters above the ground in an an unobstructed location. At sea, this might be a close reflection of what we experience, but inland, or near land where the wind is blowing offshore, the actual wind speed near the ground may be affected by things like hills, valleys and trees. The speed given is an average over 5 or 10 minutes and the wind will constantly vary above and below this value. Typically, we can expect gust of a third greater than the forecast average wind, although many forecasts will predict the wind speed in gusts.

The table below describes conditions at each level of the Beaufort Scale, along with wind speeds in other units. The ‘speed against wind’ column gives a rough idea of how fast an experienced group might be able to paddle upwind - for less experienced groups, the drop in speed with increasing headwind will be more dramatic. The ‘limit of adequate reserve’ give some idea of how long a competent paddler might be happy paddling in the specified conditions.

| Beaufort force | Speed in knots | Sea conditions | Land conditions | Paddling | Speed against wind (knots) | Limit of adequate reserve (hours) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1-3 | Small ripples | Smoke drifts, but wind vanes don’t move | Easy | 3 | 8 |

| 2 | 4-6 | Small wavelets that don’t break | Wind felt on face, leaves rustle and wind vanes move | Easy, small choppy waves start to form. | 3 | 8 |

| 3 | 7-10 | Large wavelets, which occasionally break | Leaves and twigs in motion, light flags extend | Fairly easy. Noticeable work paddling into headwind. Novices struggle in crosswind. | 2.75 | 7 |

| 4 | 11-16 | Small waves, frequent white horses | Raises dust, small branches move | Effort into headwind. Following seas start to form. Novices struggle to control the boat. Can be difficult to keep groups together unless all are competent. | 2.75 | 4 |

| 5 | 17-21 | Moderate longer waves. Many white horses, some spray | Small trees sway | Hard effort and paddle flutter. Cross winds awkward. Constant effort and concentration required to control the kayak. | 2.5 | 2 |

| 6 | 22-27 | Large waves, extensive foam crests and spray | Large branches in motion, hard to use umbrellas | Very hard effort. Limit of paddling any distance into wind. Following seas demand concentration. Only suitable for short trips by experienced paddlers. | 2.25 | 1 |

| 7 | 28-33 | Sea heaps up, foam starts to streak | Whole trees in motion, inconvenient to walk against wind | Strenuous and likely dangerous. Following seas need expertise. Paddling across wind very hard. | 1.5 | 0.5 |

Note that many weather apps allow the user the option of choosing the units that the wind speed is presented in. The Beaufort scale might be a good choice for those learning how to interpret forecasts - it proves a simple scale that relates directly to sea conditions. Many more experienced sea paddlers prefer to use knots to enable greater precision in their understanding of the wind… but most will still be relating this to the Beaufort scale in their minds.

1.2.2 Effects of land on wind

Most people will be aware that land features can affect the local wind around them - on a windy day, you can often find shelter behind a crag facing away from the wind. In fact, the land has a marked effect on the wind, often affecting wind patterns 10 miles or more out to sea. The effects of land features on the wind are going to be important for sea kayakers who mostly spend their time near the coast.

1.2.2.1 Sheltering from the wind

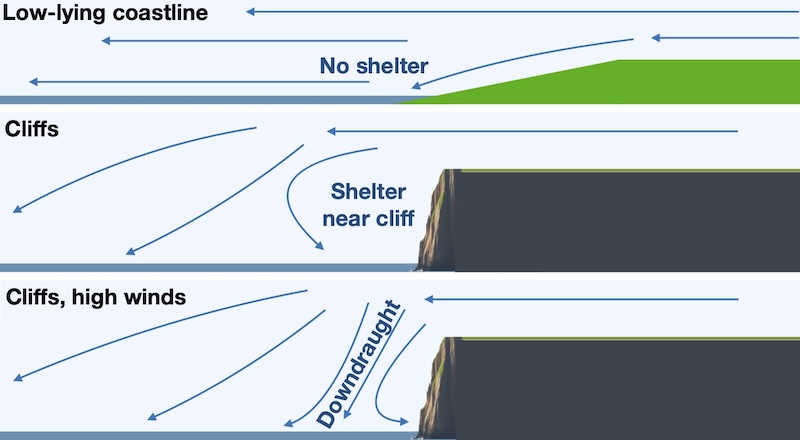

There will sometimes be some shelter from the wind on coastlines where the wind blows offshore. However, this does rely on the coastline having some height - e.g. from cliff, steep hills or a tall forest. If the land slopes gradually to the sea, there may be much less shelter:

Downwind of a tall obstruction, eddies may form, and the local wind may even be blowing lightly back towards the obstruction.

In high winds, there will still often be shelter below cliffs. However, sudden downdrafts can blow down from the cliff onto the water. These winds can scatter a group and blow strongly enough to capsize inexperienced paddlers.

Notes that the shelter provided by a steep coastline is limited to the area immediately below the steep coast. Paddlers who stray away from the coast will find the wind strength increasing, posing a danger of being blown out to sea.

1.2.2.2 Friction

The wind is slowed down close to the earth’s surface by friction. The sea is relatively smooth, and winds at sea are often 80-90% of the high-level wind. The land typically has more features and is rougher - it often slows the wind to 50% of the high-level windspeed. As a result, we should be wary of estimating winds out at sea from those which we experience on the journey to our launch point.

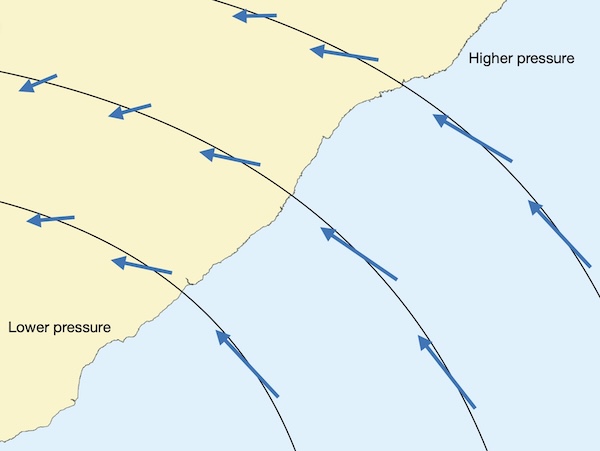

Because of the Coriolis effect, the high level wind tends to follow the isobars - lines of equal pressure. When the wind is slowed at lower levels, the Coriolis effect is less, so the wind tends to angle to flow inward towards areas of lower pressure.

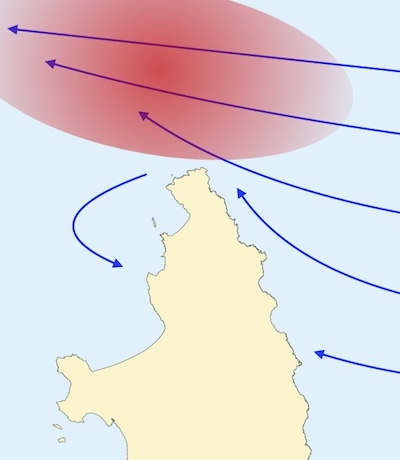

As a result, the wind will tend to turn to the left as it flows onshore (in the northern hemispehere). If wind blows offshore, it will tend to accelerate and turn to the right.

When the wind blows nearly parallel to the coastline, this can have interesting effects.

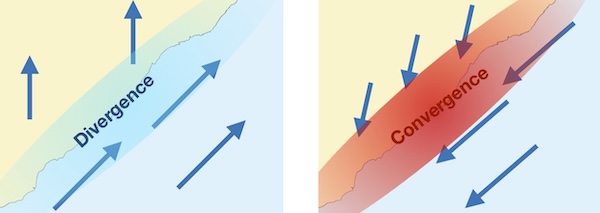

If the wind is blowing along a coastline, or slightly onshore, with the land on its left, the wind will tend to turn to the left as it blows onto the shore. The result is a zone of diverging wind over the coast, resulting in lighter winds. If the wind is blowing along the coast, or slightly offshore, with the land on its right, the wind will turn right as it blows offshore. The wind will hence converge and increase in strength near the coastline.

1.2.2.3 Funneling

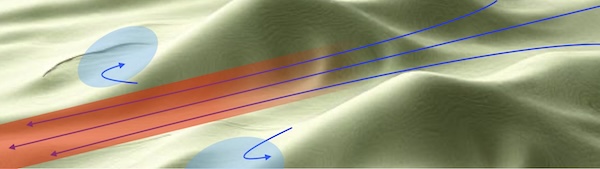

When there is a gap formed by areas of high ground, the wind may funnel through it.

This effect can happen at any breaks in a steep coastline. On a windy day with an offshore wind, you’ll often find strong winds blowing out of bays that break up an otherwise steep coastline.

Similar effects can occur at headlands, especially when they have high land on them

As we shall see, tidal streams behave similarly, and waves also tend to concentrate energy at headlands. As a result, the conditions at headlands can be much more challenging than in adjacent bays.

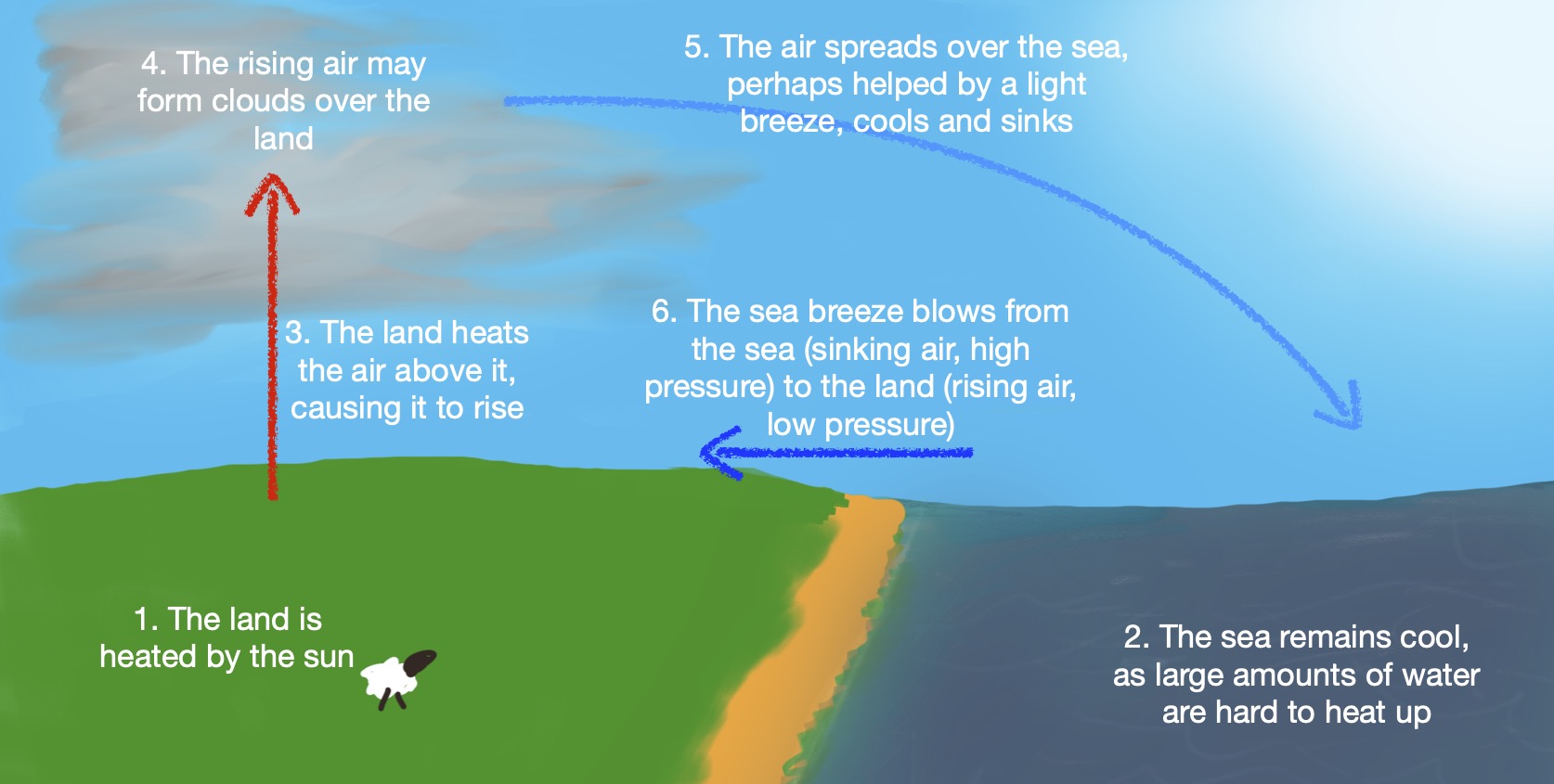

1.2.3 Sea and land breezes

Sea breezes can develop on sunny days with light winds, especially in Spring and earlier Summer. Being a large body of water, the sea’s temperature doesn’t change much during the day. However, the land will heat up substantially and warm the air above it. This causes air over the the land to rise, often forming cumulus clouds.

Air from the sea moves towards the land due to the reduced pressure created by the rising air. Ultimately, this sets up a circulation with air moving from sea to land, being warmed, rising, cooling and spreading back over the sea.

The sea breeze can create a strong onshore wind in the afternoon on warm days.

A related set of effects lead to winds being in general stronger during the day and especially the afternoon than they are during the night and morning, even when sea breezes don’t occur.

At night, the opposite effect can occur. The land loses heat quickly, whilst the sea tends to remain at a constant temperature. As a result, a ‘land breeze’, blowing from the land out to sea, can occur.

1.2.4 Anabatic and katabatic winds

In hilly areas, heating of mountain slopes can lead to localised rising air, in a manner similar to a sea breeze. This effect, known as an ‘anabatic wind’, can replicate or increase the sea breeze effect.

In evenings or overnight, mountain slopes can cool faster than the surrounding low lying land and any nearby sea. The air above these slopes cools and becomes denser. Gravity pulls this cool air down the slope, creating a katabatic wind. In some areas of the world, especially around ice sheets, these winds can be sudden and violent.

1.2.5 Wind, waves and tide

When wind blows over the water, it creates waves. The harder and longer the wind blows, the higher the waves. Swells are caused by winds and storms far away - and they often arrive on our shores on days that aren’t windy.

When waves move against a stream of moving water, the waves become steeper and break. The opposite happens when waves travel in the same direction as the stream - the waves flatten out. This effect can happen:

Due to tidal streams at sea - against either wind created waves (known as ‘wind against tide’) or swells

Due to flows in rivers and estuaries - where the flow out of the river meets swell or wind waves from the open sea

These effects can have a significant effect on conditions.

There’s much more on wind, waves, tide and how they interact in the surf and swell section.

1.2.6 Accounting for wind

We need to think about the wind in relation to the coastline that we’re paddling. Wind speed and direction are a critical element in deciding whether and where to go paddling. It might be:

Onshore - we’ll be exposed to the wind and waves, and it may push it towards a hazardous shoreline.

Offshore - we may be able to find shelter from the land, but need to be aware of the hazards of being pushed offshore. If the coastline is steep enough, there will likely be shelter near it, but this shelter will rapidly diminish and the wind strength will increase away from the shoreline. This can be a serious danger, especially for weaker paddlers or SUPs - Data obtained from the RNLI covering a period from 2020 - 2022 show that 54% of SUP rescues requiring RNLI assistance, cited offshore winds as a contributing factor. This is an increase from 33% in 2019. If the shoreline is flat, there may be limited shelter. Having said all that, sea kayakers will often choose coastlines with offshore winds to seek shelter on windier days.

Along the coastline from in front of us - which is going to make progress hard work.

Along the coastline from behind us - which may help our progress, as long as we have the skills to paddle downwind in the forecast wind and wave conditions… and, of course, if we have considered if we need to get back upwind later in the day.

Too strong for the competence of the group to handle… especially given how fatiguing paddling in wind can be. As a guide, anything more than force 3 can feel very challenging to inexperienced paddlers.

If the wind is strong (say force 4 or more), it often makes sense to seek coastlines that are sheltered from the wind. Be aware that the wind on these coastlines will blow offshore, creating a potential hazard. What seems like a light wind close to land and cliffs may be a strong wind further out. If the group gets blown away from land, getting back to shore may be difficult.

The amount of shelter that the land provides depends on the topography. Flat land without vegetation will provide little shelter. Tall cliffs are likely to provide excellent shelter from the wind - but beware downdrafts in very windy conditions. Any steep coastline, even if cliffs are only a few meters high, can provide useful shelter if a group stays close in under the cliffs. Some coastlines that provide good shelter can have areas where the wind blows strongly off the land. This can occur at gaps in cliff lines and where valleys that run parallel to the wind run down to the sea.

It also makes sense, if planning a round trip, to start by paddling upwind, so that the group gets blown home. This provides a significant safety margin compared to a day that starts downwind.

It’s also worth checking how the wind is blowing in relation to any tidal streams - if the wind is blowing opposite to the tidal stream, rough conditions will often result. There’s more on this effect in the notes on tide and waves.

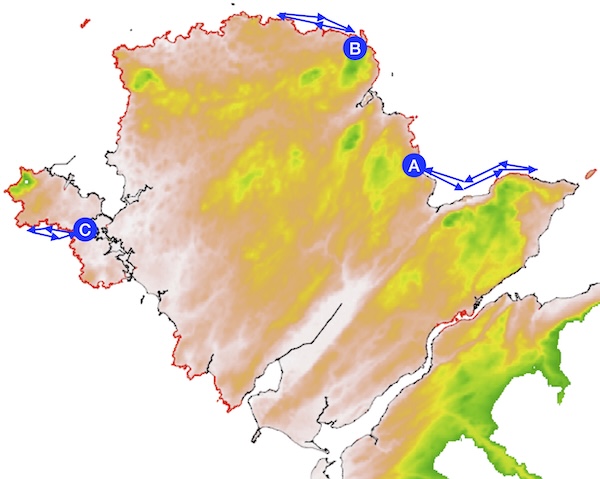

The map below show the island of Anglesey with elevation shown (green areas are ~150m) and cliffs shown as red stretches of coastline.

You are contemplating the paddles shown, all coastal round trips departing and returning to points A, B or C. What is the best option given the following wind forecasts:

Force 1-2 westerly?

Force 3 easterly?

Force 5 south-westerly?

Force 8 south-westerly?

A force 1-2 wind will have less influence on our choice of paddle, so A,B or C will be possible. It may still be good practice to paddle upwind first in case the wind increases (as paddles B and C do), but we might expect paddle A to be well sheltered from this light wind on the east side of the island.

With a force 3 wind, it is sensible to paddle upwind first, then be pushed back to the start by the wind later in the day. Only paddle A starts upwind with an easterly, so this seems the best option.

We’ll likely want to shelter from a force 5 wind. Being on a coast open to the south-west, paddle C will be exposed to the wind. The low-lying valley across the island means that there will likely be little shelter for paddle A. Paddle B makes the most sense. It is sheltered by some higher ground and some sea cliffs. It begins by paddling against any westerly component of the wind blowing along the coast.

In a force 8 wind, shelter is likely to be imperfect on any of Anglesey’s coastlines, given it’s a reasonably low-lying island. The best option is likely to be taking a day off paddling.