5.10 Navigating in open water

5.10.1 Dead reckoning

If you’ve done your chart work to find your expected positions for each hour and have a watch, you can obviously estimate your position. However, it’s nice to some other methods to confirm that you are where you expect to be.

5.10.2 Fixes and cross bearings

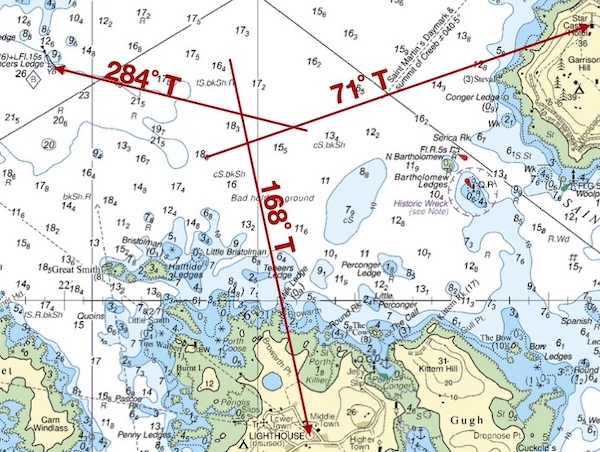

The 3 (or two) point fix described previously can be a useful approach to find your position in open water.

In practice, 3 point fixes are time consuming and fiddly to do on the deck of a kayak. Given that you often have a fairly good idea of what track you’re on, a single cross-bearing can often be a quick way to get a good estimate of position.

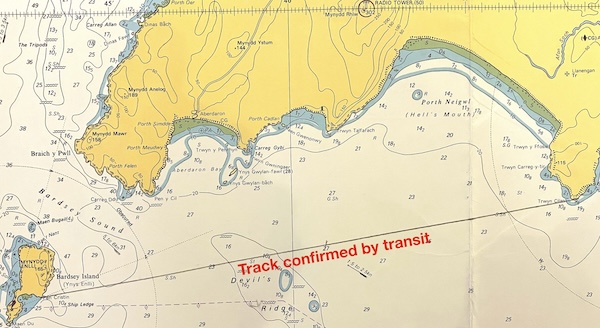

You are paddling from the small harbour on Bardsey Island to the headland of Trwyn Cilan. You are keeping on track in the strong tidal streams by using a transit between the headland and the hills in the distance behind it. You notice a radio mast on the hills to you left, and use your compass to determine that the bearing from you to the mast is 10˚. Where are you?

Given you’re following a transit from Bardsey to to Tywyn Cilan, you can be sure that you’re on a straight line between your start and finish points. You might have already sketched this line on your chart before leaving the island:

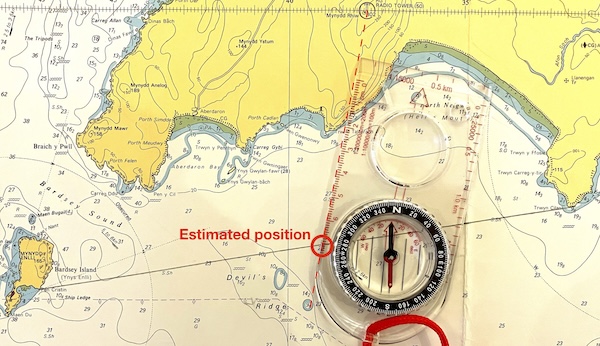

We can set our compass to 10 degrees and place it on the chart pointing at the radio mast

Note that this is intended as a quick and approximate fix - the compass baseplate isn’t long enough to reach the radio mast on the chart and the compass is only set approximately. However, it’s good enough to tell us that we’re about halfway across the crossing.

5.10.3 Distance off

Open crossings always seem to involve a lot of time staring at a destination that never seems to get any closer. It’s helpful to have some methods to estimate how far you are from the destination shoreline. As you’re likely fairly confident on your track (and can a bearing to the destination to confirm), knowing the distance still to paddle allows you to fix position. And debating how far you think it is with your companions might be a good way to break the tedium!

5.10.3.1 Resolvable detail method

In his excellent book Sea Kayak, Gordon Brown gives the following hints on how to judge how far you might be from a shoreline:

| Distance | Resolvable detail |

|---|---|

| 100 m | Possible to identify people by facial features |

| 200 m | Can see faces and clothing colours |

| 500 m | Can identify people by movement and shape. Small buoys and paddle blades are visible. |

| 1 km | People seen as dots. Can resolve individual windows on houses. Large buoys visible. |

| 1.5 km | Can see individual trees. Paddle flash, when a paddle catches the sun, can be seen. |

| 2 km | Can see individual houses (and perhaps large trees) and resolve cars from bigger vehicles. |

| 3 km | Limit of kayak-to-kayak visibility. Can separate trees for other vegetation. Paddle flash may still be visible. Flat beaches disappear. |

5.10.3.2 Subtended angle method

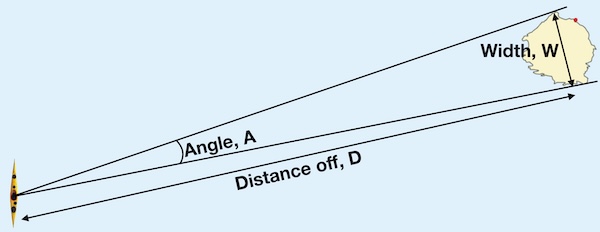

This method involves measuring the apparent angle of some distant object and comparing this to the width of the object on your map.

The distance off can be estimated as:

Distance off = 60 X Width / Angle

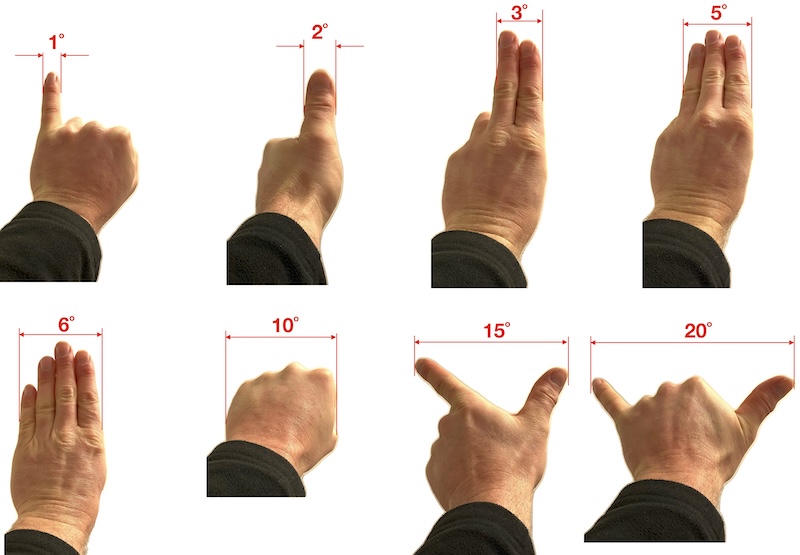

The angle can be measured by comparing compass bearing to either side of the object, but what makes this method practical for use in sea kayak is that angles can be estimated from holding your hand out at arms length:

The island of Lundy is about 2.7 nautical miles long, north to south. Whilst approaching Lundy from the east, you notice that Lundy has the same width as your splayed hand thumb to pinkie. How far from Lundy are you?

The angle indicated by your splayed hand is about 20˚. Using the relation:

Distance off = 60 X Width / Angle

Distance off = 60 X 2.7 / 20 = 8.1 nautical miles.

If you intended to use this method, you might have calculated 60 X 2.7 = 162 ahead of time, so that the only mental arithmetic that you have to do on the water is to divide 162 by 20.

Image background: Nilfanion/Wikipedia. Manipulated.

5.10.4 GPS

On a long open crossing, away from shore with few waymarks, using a GPS to navigate is an obvious choice. Traditionalists have long argued that relying on an electronic device that can break or malfunction for navigation is unwise. They’re probably right - but nowadays the obvious solution is to take several GPS units with you. If a group of 4 each possess a dedicated GPS unit, a smartphone with wayfinding apps and GPS watches, it’s hard to imagine everything failing at once.

Simply reading your position as latitude and longitude off a GPS and transcribing it onto the chart is slow and error prone. A better approach is tell your GPS your destination ahead of time (type it in on the shore, or even at home whilst you’re planning the trip) and get it to tell you the distance and bearing to there.

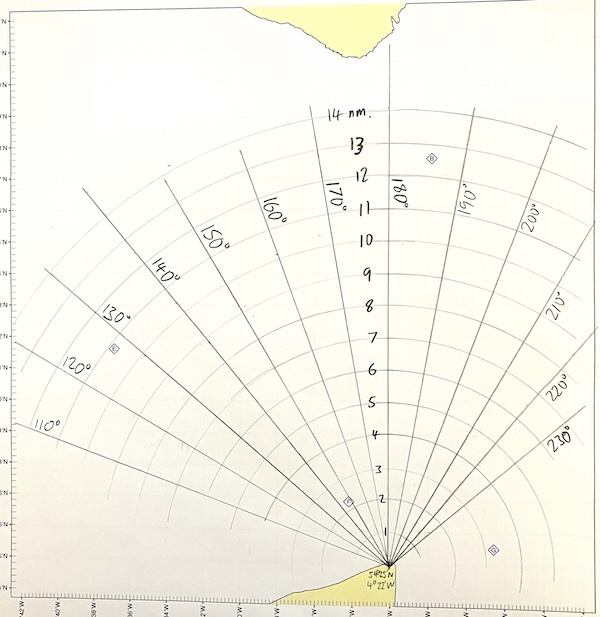

To make things easier, it helps to do some pre-work with your chart. Marking the chart with a ‘spider’s web’ of bearing and distance information allows to see at a glance where you are from a GPS bearing and distance to travel.