Be sure to also read Chapter 03 of Calling Bullshit Bergstrom and West (2020).

Optional reading https://www.nature.com/articles/492180aMotivating scenario: You have seen or heard about statistics, but you don’t really know what people are getting at. You hear words like “p-value”, “statistically significant”, “effect size”, “bias”, or “nonindependent” but can’t pinpoint exactly what they mean?

Learning goals: By the end of this chapter you should be able to

- Get a sense of what motivates statisticians.

- Be able to explain the difference between a population and a sample, a parameter and an estimate, the relationship between these four concepts, and the things which can make a sample deviate from a population.

- Have a sense of why as statisticians, we must consider the type of data and variables in building models.

- Understand the differences in motivation and what we can get out of an observational and experimental study.

Goals of (Bio)stats

Statistics claims to be obsessed with the TRUTH. It’s meant to be a way of understanding the world. It’s meant to describe and differentiate, and ideally, to tease apart causation from correlation. These three goals of statistics (below) are the beams of light we, as statisticians, try to shine on questions. That is – these three things are what you call a statistician to do.

- Estimation

- Hypothesis testing

- Causal inference

My goal is to enable you to unleash these powers. But also to realize that on their own, estimation, hypothesis testing, and even causal inference are of pretty limited utility — we could go around estimating useless trivia, or testing hypotheses that have little to do with our motivating questions, or separating between unlikely or non-exclusive causes. As such, in BIOSTATS our goals are more ambitious — we constantly ask:

- What is the motivating biological question?

- What experiments can I do/have been done and/or data can I collect to address this question?

- How can I design this experiment and/or collect these data in a way that will map cleanly onto both a statistical model and my motivating idea?

- Do results support an interesting conclusion?

- What are the shortcomings of statistical models and causal frameworks in the analysis?

- How do I best communicate my results (including estimates, visualizations, conclusions, and caveats)?

](images/howietweet.png)

Figure 1: What question re you trying to answer? link to tweet

Sampling from Populations

To a statistician the TRUTH is a population – a collection of all individuals of a circumscribed type (e.g. all grasshoppers in North America), or a process for generating these individuals (see note below). We characterize a population by its parameters (e.g. its TRUE mean, or its TRUE variance).

However, it is often impractical or impossible to study every individual in a population. As such, we often deal with a sample – a subset of a population. We characterize a sample by taking an estimate of population parameters.

So a major goal of a statistical analysis is how to go from conclusions about a sample which we can measure and observe, to the population(s) we care about. In doing so we must worry about random differences between a sample and a population (known as Sampling Error), as well as any systematic issues in our sampling or measuring procedure which will cause estimates to reliably differ from the population (known as Sampling Bias).

Sampling Error

Estimates of any sample will differ somewhat from population parameters by chance sampling and/or imprecise measurement. This is why we always consider and report uncertainty in estimates and note that chance can contribute to any result. Much of this course focuses on acknowledging and accommodating sampling error. We can reliably decrease sampling error by increasing the sample size. Note that despite its name, sampling error does not imply that the researcher made a mistake.

I therefore think it’s more appropriate to call this chance deviation of estimates away from parameters “The First Law of sampling” rather than sampling error.

Sampling Bias

](https://imgs.xkcd.com/comics/selection_effect_2x.png)

Figure 2: Image from xkcd

There are many ways for samples to systematically deviate from the population.

For example, non-randomly selected individuals will likely differ from the population in important ways. e.g. students who raise their hand in class are perhaps more likely to know the answer than a randomly chosen student, or brightly colored individuals are more likely to be spotted than drab individuals. Such phenomena are known as volunteer bias.

Another devious form of bias is known as survivorship bias, in which survivors differ from a population in critical ways. For example, students at the University of Minnesota likely had higher high school GPAs than a random sample of individuals from across the Twin Cities of the same age.

](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/98/Survivorship-bias.png/256px-Survivorship-bias.png)

Figure 3: Image from Wikipedia

A classic example of survivorship bias is this distribution of gunshot holes in airplanes returning from WWII — the army initially reacted to the prevalence of holes in the wings and tail by suggesting that such parts of the plane be reinforced. However, Abraham Wald pointed out that airplanes that did not return were the ones who needed more help and these were likely shot where we don’t see holes.

(Non) independence

Most (intro) stats assumes that samples are independent. If observations in a sample are independent of one another, the probability that one individual is studied is unrelated to the probability that any other individual is studied. While this is desirable, it is sometimes impossible, so we address methods for accommodating non-independence later in the term.

Models and Hypothesis Testing

Statistical Models

While statisticians claim to be interested in TRUTH and POPULATIONS, they quickly give up on this. Rather than characterizing a population in full, or describing the complex processes such as metabolism, meiosis, gene expression that generate data, statisticians build simple models to abstract away the biological complexity and make questions approachable. As such, rather than fully describing a distribution from a population, statisticians often use well characterized statistical distributions to approximate and model the actual biological process.

So, while we use statistics to search for truth, we must always remember this underlying fiction. As we conduct our statistics always consider the relationship between our biological models/phenomena and the stats model we use to approximate it. If our statistical model is inappropriate for our biological question, we cannot reasonably take home much from the result. That said, we’re doing statistics not physiology, and so our goal is to make use of appropriate statistical abstractions, not to reconstruct the whole biological system (even if we’re doing statistics on physiology).

“All models are wrong, but some are useful.”

Hypothesis Testing

A common use of statistics — especially the statistics we focus on this term — is hypothesis testing. Here, we use our estimates from samples to ask if data come from populations with different parameters. This approach often (but not always) relies on statistical models.

Inferring Cause

The third major goal of statistics (in addition to estimation and hypothesis testing) is inferring causation.

What is a cause? Like so much of statistics, understanding causation requires a healthy dose of our imagination. Specifically, we imagine multiple worlds. For example, we can imagine a world in which there was some treatment (e.g. we drank coffee, we got a vaccine, we raised taxes etc) and one in which that treatment was absent (e.g. we didn’t have coffee, we didn’t raise taxes etc), and we then follow some response variable of interest. We say that the treatment is a cause of the outcome if changing it will change the outcome, on average. Note for quantitative treatments, we can imagine a bunch of worlds where the treatments was modified by some quantitative value.

In causal inference, considering the outcome if we had changed a treatment is called counterfactual thinking, and it is critical to our ability to think about causes.

Confounds and DAGs

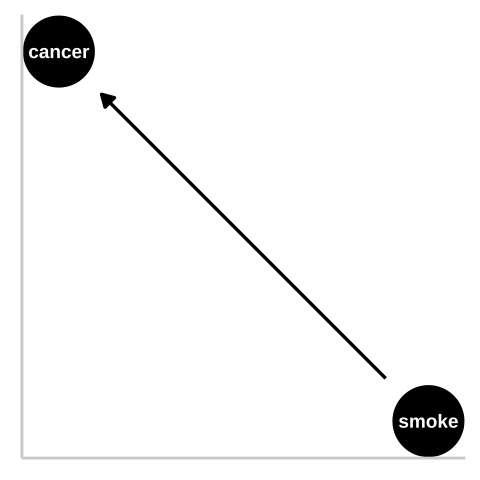

Say we saw a strong association between smoking and lung cancer from an observational study, and wanted to know if smoking causes cancer.

Figure 4: We could represent this causal claim with the simplest causal graph we can imagine. This is our first formal introduction to a Directed Acyclic Graph (hereafter DAG). This is Directed because WE are pointing a causal arrow from smoking to cancer. It is acyclic because causality in these models only flows in one direction, and its a graph because we are looking at it. These DAGs are the backbone of causal thinking because they allow us to lay our causal models out there for the world to see. Here we will largely use DAGs to consider potential causal paths, but these can be used for mathematical and statistical analyses.

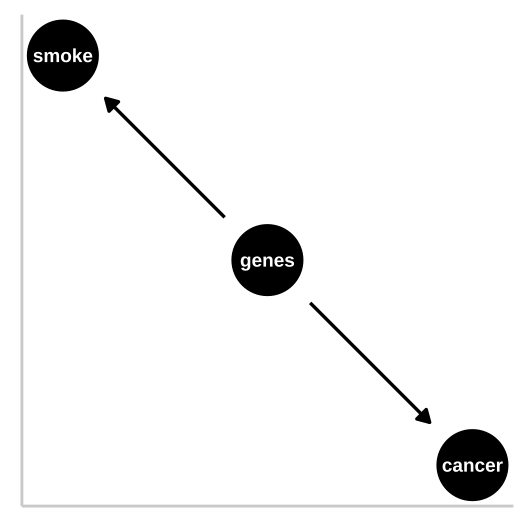

Confounds

Figure 5: R.A. Fisher – a pipe enthusiast, notorious asshole, eugenicist, and the father of modern statistics and population genetics was unhappy with this DAG. He argued that a confound could underlie the strong statistical association between smoking and lung cancer. A confounding variable – is an unmodelled variables which distort the relationship between explanatory and response variables – can bias our interpretation. Specifically, Fisher proposed that the propensity to smoke and to develop lung cancer could be causally unrelated, if both were driven by similar genetic factors. Fisher’s causal model is presented in th DAG to the right – here genes point to cancer and to smoking, but no arrow connects smoking to lung cancer.

In the specifics of this case, Fisher turned out to be quite wrong – genes do influence the probability of smoking and genes do influence the probability of lung cancer, but smoking has a much stronger influence on the probability of getting lung cancer than does genetics.

DAGs

I’ve introduced two DAGs so far.

Figure 4 is a causal model of smoking causing lung cancer. Note this does it mean that nothing else causes lung cancer, or that everyone who smokes will get lung cancer, or that no one who doesn’t smoke will get lung cancer. Rather, it means that if we copied each person, and had one version of them smoke and the other not, there would be more cases of lung cancer in the smoking clones than the nonsmoking clones.

Figure 5 presents Fisher’s argument that smoking does not cause cancer and that rather, both smoking and cancer are influenced by a common cause – genetics.

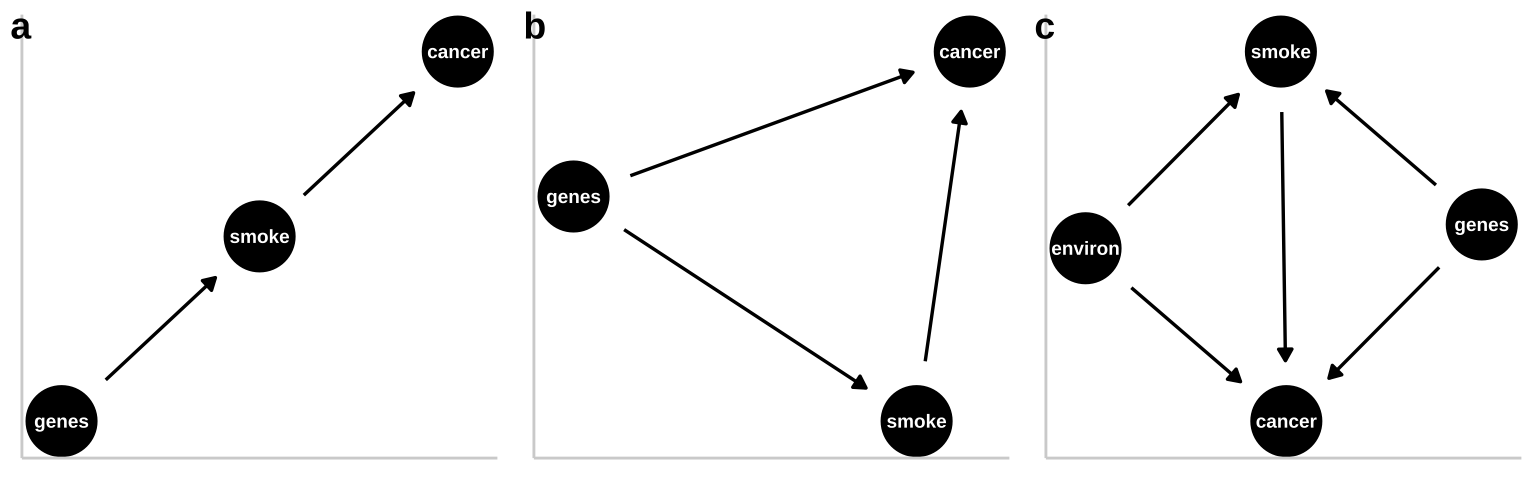

These are not the only plausible causal models for an association between smoking and cancer. I present three other possibilities in Figure 6. Have a look!

Figure 6: Three plausible DAGs concerning the relationship between smoking and cancer. a Genes cause smoking, and smoking causes cancer. b Genes cause cancer and genes cause smoking, and smoking causes cancer. c Environmental factors cause smoking and cancer, and genetics cause smoking and cancer, while smoking too causes cancer.

Types of Studies

This is why randomized control experiments are our best to learn about causation. In a randomized control experiment, treatments are randomly assigned to individuals – so we randomly place participant in these alternative realities that we imagine and look at the outcome of alternative treatments. That is, we bring our imaginary worlds to life. As such, randomized control experiments are the gold-standard for establishment of causation. If neither the subjects nor the experimenters know the treatment, a randomized control study can allow us to infer causation.

However, some caution is warranted here – a causal relationship in a controlled experiment under specified settings may not imply a causal relationship in nature. For example, exceptionally high doses of a pesticide may cause squirrels to die, but this does not mean that the smaller dose of insecticide found around farm fields is responsible for squirrel death. Additionally, randomized control experiments are often unfeasible, impractical, and/or impossible. As such, we often have to carefully tease apart causal claims from observational studies and be wary of unjustified causal claims.

For example, the finding that people who smoke are more likely to get cancer comes from many observational studies. In an observational study, treatments are not randomly assigned to individuals. Therefore, confounding variables – unmodelled variables which distort the relationship between explanatory and response variables – can bias our interpretation. A simple association between smoking and lung cancer might suggest smoking causes lung cancer, or both are caused by stress, or genetics or whatever. We therefore must show extreme caution when attempting to learn about causation from observational studies. However, the rapidly developing field of causal inference is establishing a set of approaches that can help us disentangle correlation and causation.

So to distinguish between the claim that smoking causes cancer and Fisher’s claim that genetics is a confound and that smoking does not cause cancer, he could randomly assign some people to smoke and some to not. Of course, this is not feasible for both ethical and logistical reasons, so we need some way to work through this. The DAGs provide one way to aid in our thinking. For example, writing down a (few) DAGs can help us think through causes better and develop new hypotheses to distinguish causes. If we proposed genetics was a common cause of smoking and lung cancer, we could conduct an observational study of pairs of twins with one smoker and one nonsmoker and compare the probability of lung cancer in the smoker and nonsmoker. In fact, as discussed above (Hjelmborg et al. 2017) conducted such an experiment and ruled out Fisher’s explanation.

Remember: the distinction between an experimental and an observational experimental study is not about the equipment used or the lab vs. the field. For example, comparing patterns of methylation between live bearing and egg laying species of fish is an observation, not an experiment, as we did not randomly assign live-bearing or egg-laying to fish in this study.

Quiz

Figure 7: The accompanying quiz link

Homework

The homework (due by 9 am on Friday) consists of:

Complete the quiz (above).

Reflect on the Calling Bullshit (Bergstrom and West 2020) reading link. What did you like? What did you learn? Why did I assign it? Be prepared to adress these question in a quiz from in class Friday.

Definitions

Population A collection of all individuals of a circumscribed type, or a generative process from which we can generate samples.

Sample A subset of a population – individuals we measure.

Parameter A true measure of a population.

Estimate A guess at a parameter that is made from a finite sample.

Sampling error describes the deviation between parameter and estimate attributable to the finite process of sampling.

Sampling bias describes the deviation between parameter and estimate attributable to non representative sampling.

Independence Samples are independent if the probability that one individual is studied is unrelated to the probability that any other individual is studied.

Explanatory variables are variables we think underlie or are associated with the biological process of interest.

Response variables are the outcome we aim to understand.

Numeric variables are quantitative – they can be assigned a meaningful value on the number line.