35 Tests comparing two odds or proportions

You have learnt to ask a RQ, design a study, classify and summarise the data, construct confidence intervals, and perform some hypothesis tests. In this chapter, you will learn to:

- identify situations where conducting a test for comparing two odds or proportions is appropriate.

- conduct hypothesis tests for comparing two proportions, using a \(z\)-test.

- conduct hypothesis tests for comparing two odds, using chi-square tests in software output.

- determine whether the conditions for using these methods apply in a given situation.

35.1 Introduction: meals on-campus

As seen in Sect. 28.1, Mann and Blotnicky (2017) examined the relationship between where university students usually ate, and where the student lived (Table 35.1).

| Most off-campus | Most on-campus | |

|---|---|---|

| Living with parents | \(52\) | \(\phantom{0}\phantom{0}2\) |

| Not living with parents | \(105\) | \(\phantom{0}24\) |

A graphical summary is shown in Fig. 28.1 (left panel), and a numerical summary in Table 35.2. (The details of the computations appear in Sect. 28.2.)

| Odds of having most meals off-campus | Proportion having most meals off-campus | Sample size | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Living with parents | \(26.000\) | \(96.3\) | \(\phantom{0}54\) |

| Not living with parents | \(\phantom{-}4.375\) | \(81.4\) | \(129\) |

| \(\phantom{-}5.943\) | \(0.149\) |

Since two groups are being compared, subscripts are used to distinguish between the statistics for the two groups; say, Groups \(A\) and \(B\) in general (Table 35.3). For this example, we use \(N\) to refer to students not living with their parents, and \(L\) for students living with their parents.

The parameter can be either a difference between two population proportions, or a population odds ratio. For example, the parameter could be difference between population proportion of students eating most meals off-campus, comparing students living with their parents, to students not living with their parents; that is, \(p_L - p_N\). (Of course, the parameter could be defined as \(p_N - p_L\) also.) Alternatively (and equivalently), the parameter could be the population OR of eating most meals off-campus, comparing students living with their parents, to students not living with their parents.

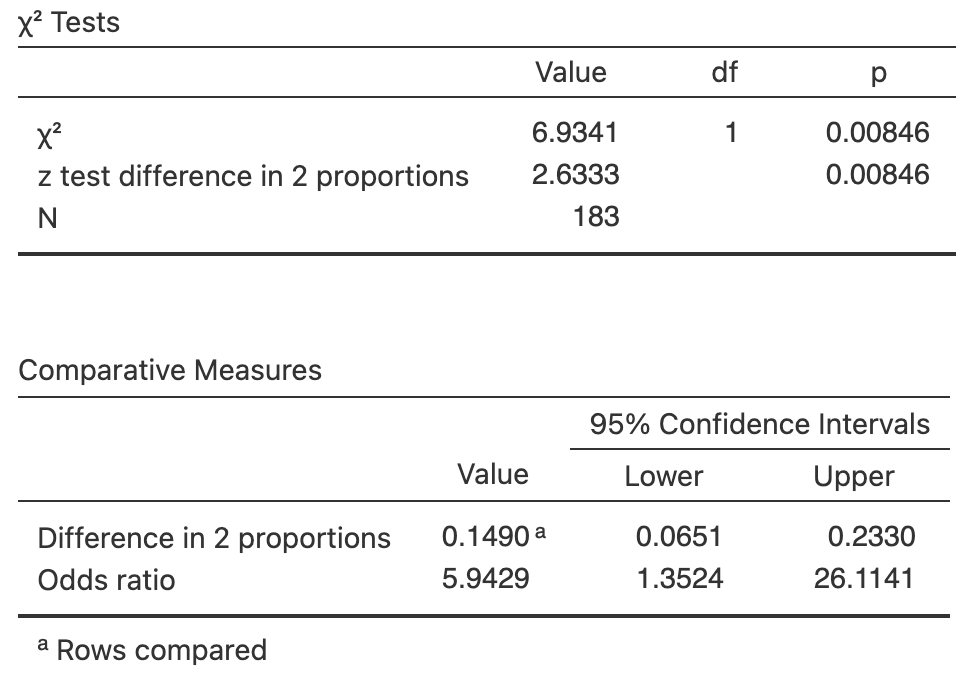

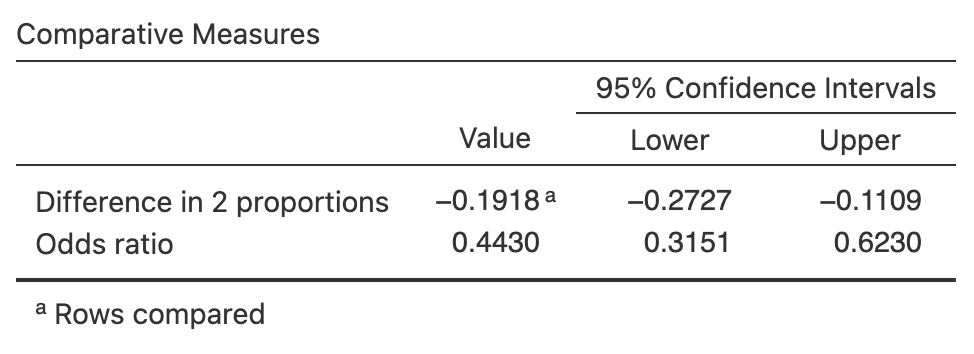

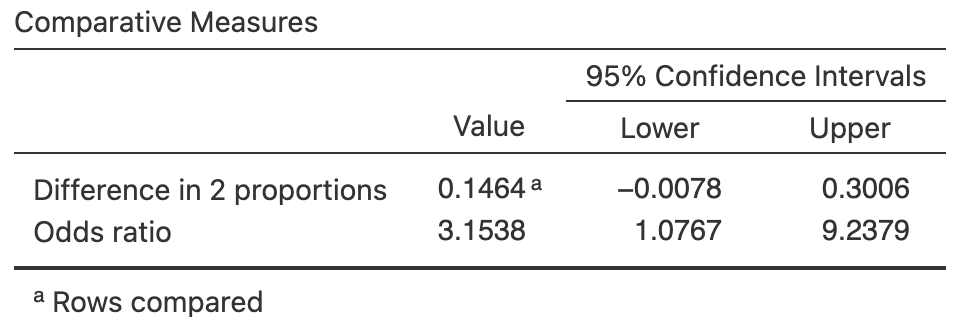

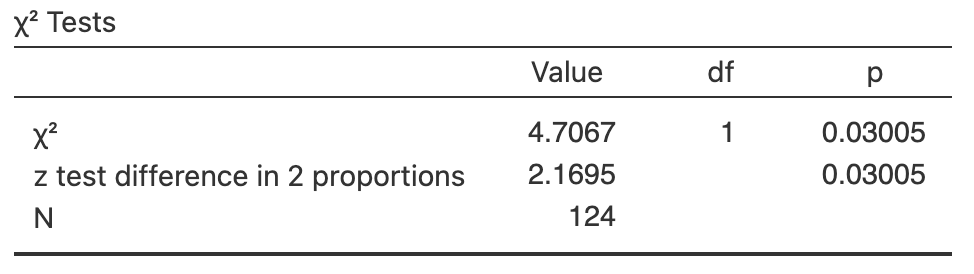

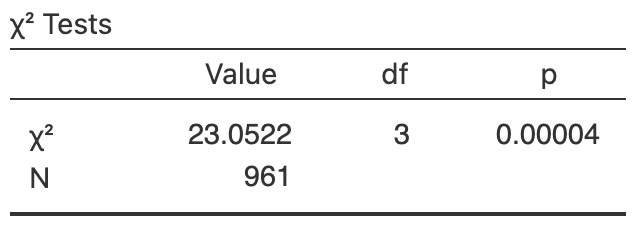

The table can be constructed with either variable as the rows or the columns. However, software commonly compares rows (for example, see the text under the bottom table in Fig. 35.1), so it makes sense to place the groups to be compared (i.e., the explanatory variable) in the rows of the table.

Then, the difference between the two proportions are usually calculated as the Row 1 proportion minus the Row 2 proportion. Similarly, the odds then can be interpreted as comparing Column 1 counts to Column 2 counts, and the odds ratio as comparing the Row 1 odds to the Row 2 odds.

The RQ and the hypotheses can be written as comparing proportions (Sect. 35.2), comparing odds (Sect. 35.3), or about odds ratios. Means are not appropriate (the data contain two qualitative variables).

| Group A | Group B | Comparing groups | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample sizes: | \(n_A\) | \(n_B\) | |

| Sample odds: | \(\text{Odds}_A\) | \(\text{Odds}_B\) | \(\text{Odds ratio} = \text{Odds}_A/\text{Odds}_B\) |

| Sample proportions: | \(\hat{p}_A\) | \(\hat{p}_B\) | \(\hat{p}_A - \hat{p}_B\) |

| Standard errors: | \(\displaystyle\text{s.e.}(\hat{p}_A)\) | \(\displaystyle\text{s.e.}(\hat{p}_B)\) | \(\displaystyle\text{s.e.}(\hat{p}_A - \hat{p}_B)\) |

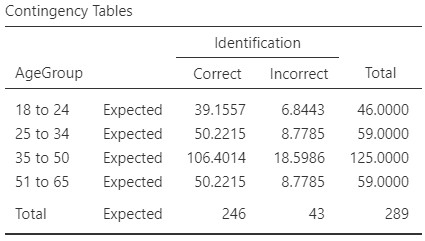

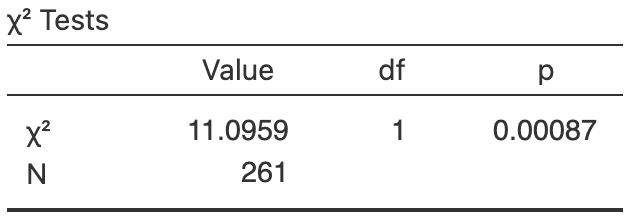

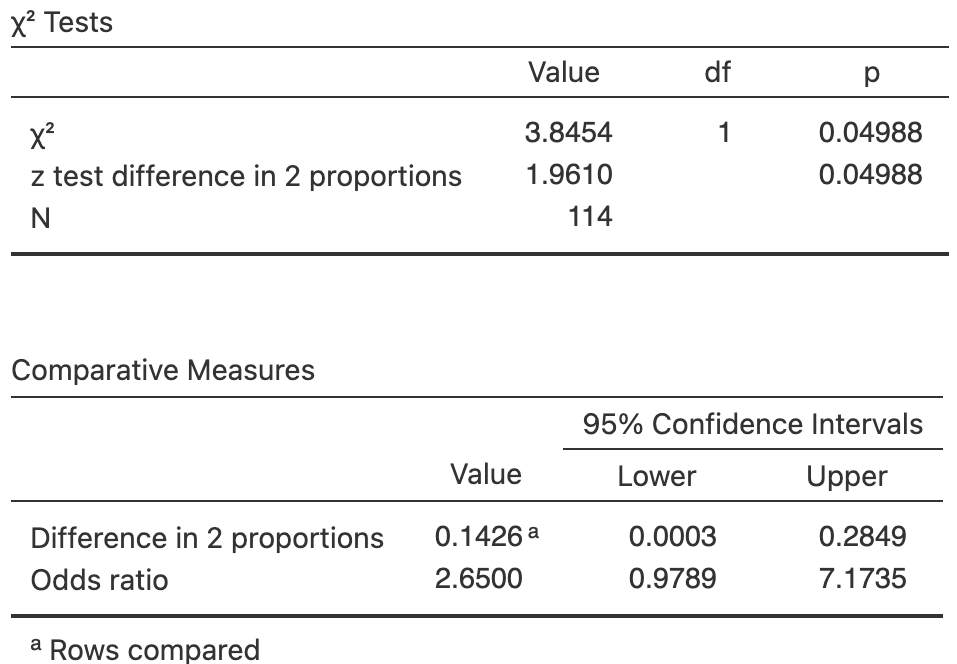

FIGURE 35.1: Software output for computing a CI and conducting a test.

35.2 Comparing two proportions: \(z\)-test

To compare the two proportions, the two-tailed RQ is:

Is the population proportion of students eating most meals off-campus the same for students living with their parents and for students not living with their parents?

As usual, the population values are unknown, so this is estimated using the statistic \(\hat{p}_L - \hat{p}_N\).

Hypothesis testing always begins by assuming that the null hypothesis is true (Sect. 32.2.1). In this context, that means assuming that the population proportion of eating most meals off-campus is the same in both groups:

- \(H_0\): \(p_L - p_N = 0\) (equivalent to \(p_L = p_N\)).

From the RQ, the alternative hypothesis is two-tailed:

- \(H_1\): \(p_L - p_N \ne 0\) (equivalent to \(p_L \ne p_N\)).

Because we assume the null hypothesis to be true, we assume the proportions are the same for both groups. Hence, the data from the two groups can be combined to determine an overall (or common) proportion of students eating most meals off-campus: \[\begin{equation} \hat{p} = \frac{52 + 105}{52 + 105 + 2 + 24} = \frac{157}{183} = 0.85792. \tag{35.1} \end{equation}\] This is the overall proportion of students eating most meals off-campus, assuming no difference between students living with and not with their parents.

The sample proportions for the two groups (\(L\) and \(N\)) will vary from sample to sample and so have a sampling distribution (as in Sect. 30.3). The standard error of the sample proportion \(\hat{p}\) for each sample is computed using this common proportion, using the same idea as in Eq. (23.1): \[\begin{align*} \text{s.e.}(p_L) &= \sqrt{ \frac{\hat{p}\times(1 - \hat{p})}{n_L}} = \sqrt{ \frac{0.85792\times(1 - 0.85792)}{54}} = 0.047511; \text{and}\\ \text{s.e.}(p_N) &= \sqrt{ \frac{\hat{p}\times(1 - \hat{p})}{n_N}} = \sqrt{ \frac{0.85792\times(1 - 0.85792)}{129}} = 0.030739. \end{align*}\]

When computing the standard errors as part of a hypothesis test, the common or overall proportion is used to compute the standard errors.

The difference between the two proportions will vary from sample to sample too, and hence have a sampling distribution; under certain conditions (Sect. 35.4), this sampling distributiomn will have a normal distribution. The standard error of this sampling distribution for the difference between the proportions is \[ \text{s.e.}(\hat{p}_A - \hat{p}_B) = \sqrt{ \text{s.e.}(\hat{p}_L)^2 + \text{s.e.}(\hat{p}_N)^2 } = \sqrt{ 0.047511^2 + 0.030739^2} = 0.056588, \] similar to Eq. (28.1).

Definition 35.1 (Sampling distribution for the difference between two sample proportions) The sampling distribution of the difference between two sample proportions \(\hat{p}_A\) and \(\hat{p}_B\) is (when the appropriate conditions are met; Sect. 35.4) described by:

- an approximate normal distribution,

- centred around a sampling mean whose value is \({p_{A}} - {p_{B}}\), the difference between the population proportions (from \(H_0\)),

- with a standard deviation, called the standard error of the difference between the proportions, of \(\displaystyle\text{s.e.}(\hat{p}_A - \hat{p}_B)\).

The standard error for the difference between the proportions is \[ \text{s.e.}(\hat{p}_A - \hat{p}_B) = \sqrt{ \text{s.e.}(\hat{p}_A)^2 + \text{s.e.}(\hat{p}_B)^2 }, \] where \[ \text{s.e.}(p_A) = \sqrt{ \frac{p\times(1 - p)}{n_A}} \quad\text{and}\quad \text{s.e.}(p_B) = \sqrt{ \frac{p\times(1 - p)}{n_B}}, \] where \(p\) is the common (overall) proportion.

Since the sampling distribution has an approximate normal distribution, the test statistic is

\[

z = \frac{ (\hat{p}_L - \hat{p}_N) - (p_L - p_N) }{\text{s.e.}(\hat{p}_A - \hat{p}_B)} \

= \frac{ 0.14901 - 0}{0.056588}

= 2.633.

\]

Since the sampling distribution has an approximate normal distribution, the approximate \(P\)-value can be computed from normal distributions (Sect. 21.6), approximated using the \(68\)--\(95\)--\(99.7\) rule, or from software output (Fig. 35.1).

The two-tailed \(P\)-value reported by software (Fig. 35.1, under the column p) is indeed small: \(0.008\) to three decimal places.

A very small \(P\)-value means strong evidence exists to supporting \(H_1\): the evidence suggests a difference between the population proportions. We write:

The sample provides strong evidence (\(z = 2.63\); two-tailed \(P = 0.008\)) that the proportion of students in the population of having most meals off-campus is different for students living with their parents (proportion: \(0.963\), \(n = 54\)) and students not living with their parents (proportion: \(0.814\), \(n = 129\); difference: \(0.149\); \(95\)% CI from \(0.0633\) and \(0.235\), higher for students living with their parents).

The conclusion includes three components (Sect. 32.8): the answer to the RQ; the evidence used to reach that conclusion ('\(z = 2.63\); two-tailed \(P = 0.008\)'); and some sample summary statistics (including the \(95\)% CI for the difference between proportions; Sect. 27.5). The conclusion also makes clear which proportion is higher.

35.3 Comparing two odds: \(\chi^2\)-test

For the \(2\times 2\) table of counts in Table 35.1, odds can be compared rather than proportions:

Are the population odds of students eating most meals off-campus the same for students living with their parents and for students not living with their parents?

If the odds are the same in the two groups, this is equivalent to an odds ratio of one. Hence, the RQ could also be written as

Is the population odds ratio of eating most meals off-campus, comparing students who live with their parents to students not living with their parents, equal to one?

Either way, the parameter is the population odds ratio, and the null hypothesis is the 'no difference, no change, no relationship' position:

-

\(H_0\): The population OR is one; or (equivalently):

The population odds are the same in each group.

This hypothesis proposes that the sample odds are not the same in the two groups only due to sampling variation. This is the initial assumption. The alternative hypothesis is

-

\(H_1\): The population OR is not one; or (equivalently):

The population odds are not the same in each group.

For comparing odds, the alternative hypotheses is always two-tailed.

In our example then:

- \(H_0\): The population odds of eating most meals off-campus are the same for students living with their parents and for students not living with their parents.

- \(H_1\): The population odds of eating most meals off-campus are different for students living with their parents and for students not living with their parents.

As usual, the decision-making process starts by assuming the null hypothesis is true: that the population odds ratio is one (i.e., the population odds in each group are equal).

35.3.1 Finding expected counts

Assuming that the odds of having most meals off-campus is the same for both groups (that is, the population OR is one), how would the sample OR be expected to vary from sample to sample just because of sampling variation? If the null hypothesis is true, the odds are the same in both groups (and the proportions are the same in both groups). That is, the proportions of students eating most meals off-campus is the same for students living with and not living with their parents.

Let's consider the implication. From Table 35.1, \(157\) students out of \(183\) ate most meals off-campus, so that \(157\div 183 = 0.8579\) of students in the entire sample ate most of their meals off-campus (the same value found in Eq. (35.1).)

If the proportions of students who eat most of their meals off-campus is the same for those who live with their parents and those who don't, then we'd expect \(0.8579\) of students in both groups to be eating most meals off-campus. (These values were also found in Sect. 28.5.) In other words, the two conditional probabilities would be the same. In that case, we would expect:

- A proportion of \(0.8579\) of the \(54\) students who live with their parents (i.e., \(0.8579\times 54 = 46.33\) students) to eat most meals off-campus; and

- A proportion of \(0.8579\) of the \(129\) students who don't live with their parents (i.e., \(0.8579\times 129 = 110.67\) students) to eat most meals off-campus.

In other words, the proportions (and hence the odds) of eating most meals off-campus is the same in each group. Those are the expected counts if the proportions (or odds) was exactly the same in each group (Table 35.4), as stated by \(H_0\).

How close are the observed counts (Table 35.1) to the expected counts (Table 35.4)?

- \(46.33\) of the \(54\) students who live with their parents are expected to eat most meals off-campus; yet we observed \(52\).

- \(110.67\) of the \(129\) students who don't live with their parents are expected to eat most meals off-campus; yet we observed \(105\).

The observed and expected counts are similar, but not the exactly same. The difference between the observed and expected counts may be explained by sampling variation (that is, the null hypothesis explanation).

The hypothesis test effectively compares the observed counts to the expected counts (assuming no relationship between the variables) over the whole \(2\times 2\) table.

You do not have to compute the expected values when you answer one of these types of RQs (software does it in the background). However, seeing how the decision-making process works in this context is helpful.

In previous hypothesis tests, the sampling distribution had an approximate normal distribution. However, the sampling distribution of the odds ratio is more complicated7 so will not be presented. We will use software output only to conduct the test.

| Most off-campus | Most on-campus | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Living with parents | \(46.328\) | \(\phantom{0}\phantom{0}7.672\) | \(\phantom{0}54\) |

| Not living with parents | \(110.672\) | \(\phantom{0}18.328\) | \(129\) |

| Total | \(157.000\) | \(\phantom{0}26.000\) | \(183\) |

35.3.2 Computing the value of the test statistic

The decision-making process compares what is expected if the null hypothesis about the parameter is true (Table 35.4) to what is observed in the sample (Table 35.1). Previously, when the summary statistics were means and the sampling distribution was a normal distribution, the test statistic was a \(t\)-score. However, the data here are not summarised by means, the sampling distribution is not a normal distribution, and so a different test statistic is needed.

Here, the test-statistic is a 'chi-squared' statistic, written \(\chi^2\). The \(\chi^2\)-score measures the overall size of the differences between the expected counts and observed counts, over the entire \(2\times 2\) table.

The Greek letter \(\chi\) is pronounced 'ki', as in kite (not 'chi' as in China). The test statistic \(\chi^2\) is pronounced as 'chi-squared'.

From the software (Fig. 35.1), \(\chi^2 = 6.934\). But what does this value mean? Is it 'large' or 'small'?

The \(\chi^2\)-value can be understood by finding the equivalent \(z\)-score, which means a \(P\)-value can be estimated using the \(68\)--\(95\)--\(99.7\) rule.

The \(\chi^2\)-value is equivalent to

\[

z = \sqrt{\chi^2}\qquad\text{for a $2\times 2$ table of counts only}.

\]

Here then, the \(\chi^2\) value is equivalent to a \(z\)-score of \(\sqrt{6.934} = 2.633\).

This is the same \(z\)-score produced when comparing two proportions (Sec. 35.2; Fig. 35.1), and hence the \(P\)-value will be the same also.

Using the \(68\)--\(95\)--\(99.7\) rule, a small \(P\)-value is expected.

The two-tailed \(P\)-value reported by software (Fig. 35.1, under the column p) is indeed small: \(0.008\) to three decimals.

Recall that \(\chi^2\) tests always have two-tailed alternative hypotheses, so two-tailed \(P\)-values are always reported.

Click on the hotspots in the following image, and describe what the software output tells us.

35.3.3 Writing conclusions

A very small \(P\)-value (\(0.008\) to three decimals) means strong evidence exists to supporting \(H_1\): the evidence suggests a difference in the population odds in the two groups. We write:

The sample provides strong evidence (\(\chi^2 = 6.934\), \(n = 54\); two-tailed \(P = 0.008\)) that the odds in the population of having most meals off-campus is different for students living with their parents (odds: \(26\)) and students not living with their parents (odds: \(4.375\), \(n = 129\); OR: \(5.94\); \(95\)% CI from \(1.35\) to \(26.1\)).

The conclusion includes three components (Sect. 32.8): the answer to the RQ; the evidence used to reach that conclusion ('\(\chi^2 = 6.934\); two-tailed \(P = 0.008\)'); and some sample summary statistics (including the \(95\)% CI for the odds ratio).

The conclusion also makes clear what the odds and the odds ratio mean. The odds are describing as the 'odds of having most meals off-campus', and the OR as then comparing these odds between 'students living with their parents and students not living with their parents'.

35.4 Statistical validity conditions

As usual, these results hold under certain conditions. The tests above are statistically valid if:

- All expected counts are at least five.

Some books may give other (but similar) conditions.

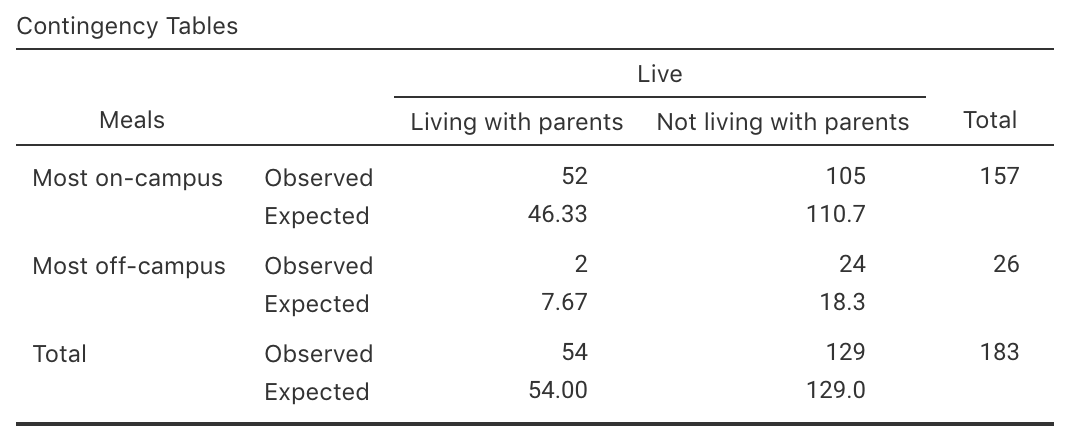

The statistical validity condition refers to the expected (not the observed) counts. In some software, the expected counts must be explicitly requested to see if this condition is satisfied (Fig. 35.2).

The units of analysis are also assumed to be independent (e.g., from a simple random sample).

If the statistical validity conditions are not met, other similar options include using a Fisher's exact test (Conover 2003) or using resampling methods (Efron and Hastie 2021).

FIGURE 35.2: The expected values, as computed by software.

Example 35.1 (Statistical validity) For the student-eating data, the smallest observed count is \(2\) (living with parents; most meals off-campus), but the smallest expected count (see Table 35.4 or Fig. 35.2) is \(7.67\), which is greater than five. This means the two tests (comparing proportions; comparing odds) are both statistically valid. The size of the expected counts is important for the statistical validity condition.

As noted in Sect. 28.5, usually, you do not have to compute these expected values, as software can produce the expected counts (e.g., Fig. 35.2). However, a quick check for the statistical validity is to compute the value of the smallest expected value, using \[ \frac{(\text{Smallest row total})\times(\text{Smallest column total})}{\text{Overall total}}. \] If this value is greater than five, the tests are statistically valid.

35.5 Tests of independence more generally: \(\chi^2\)-tests

Often a table of counts is larger than \(2\times 2\). In these situations, the RQ is worded in terms of independence, relationships or associations (but not correlations) between the variables:

Is there a relationship (or association) between one qualitative variable and another qualitative variable?

The RQ is answered using a \(\chi^2\)-test, by extending the ideas in Sect. 35.3, as demonstrated in the following example. If one of the qualitative variable has two levels, the RQ may be worded in terms of odds or proportions.

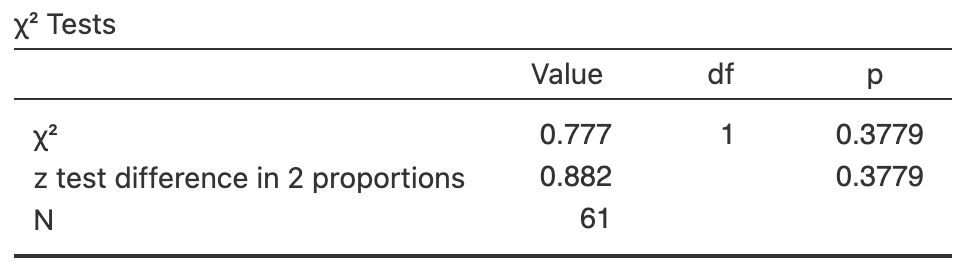

Example 35.2 (Two-way tables larger than $2\times 2$) [Dataset: RipsID]

Diez-Fernández et al. (2023) studied Spanish people's knowledge of ocean rips

(Table 35.5.

The table is a \(4\times 2\) two-way table.

The rows are the age groups, as the age groups are being compared.

The RQ is

Is there a relationship (or association) between age group and people's ability to correctly identify a rip?

Since one variable (whether the person can identify a rip) has two levels, the RQ may be worded as:

Are the odds of Spaniards correctly identifying a rip the same for each age group?

or

Is the proportion of Spaniards correctly identifying a rip the same for each age group?

| Correctly | Incorrectly | |

|---|---|---|

| 18 to 24 | \(\phantom{0}41\) | \(\phantom{0}5\) |

| 25 to 34 | \(\phantom{0}47\) | \(12\) |

| 35 to 50 | \(106\) | \(19\) |

| 51 to 65 | \(\phantom{0}52\) | \(\phantom{0}7\) |

| Odds | Odds ratio | Percentage | \(n\) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18 to 24 | \(8.200\) | \(1.104\) | \(89.1\) | \(\phantom{0}46\) |

| 25 to 34 | \(3.917\) | \(0.527\) | \(79.7\) | \(\phantom{0}59\) |

| 35 to 50 | \(5.579\) | \(0.751\) | \(84.8\) | \(125\) |

| 51 to 65 | \(7.429\) | \(88.1\) | \(\phantom{0}59\) |

The odds and percentage of people in each age group that can correctly identify rips can be computed (Table 35.6, but this is not always possible (e.g., for a \(3\times 4\) table). Odds ratios compare pairs of odds, and the odds ratios in Table 35.6 are all relative to those \(51\) to \(65\) (hence, no odds ratio is given for the \(51\) to \(65\) age group, which is the reference level). For example, the odds of someone aged \(18\) to \(24\) correctly identifying a rip is \(1.104\) times the odds of someone aged \(51\) to \(65\) correctly identifying a rip.

Because one of the variables has two levels, the hypotheses can be worded in terms of comparing odds or comparing proportions; for example:

- \(H_0\): The population odds of correctly identifying a rip is the same for all age groups.

- \(H_1\): The population odds of correctly identifying a rip is not the same for all age groups.

The alternative hypothesis encompasses many possibilities: for example, that the three odds are all different from each other, or that the odds for the first age group is different than the other two (which are the same).

For tables larger than \(2\times 2\) more generally, the hypothesis are usually worded in terms of associations or relationships between the variables (but not correlations):

- \(H_0\): In the population, there is no association between correctly identifying a rip and age group;

- \(H_1\): In the population, there is an association between correctly identifying a rip and age group.

For two-way tables, RQs can be framed in terms of ORs, comparing odds, comparing proportions, or using associations (or relationships).

For consistency: if the RQ is about the odds ratio, the hypotheses and conclusion should be about the odds ratio; if the RQ is about odds, the hypotheses and conclusion should be about the odds; and so on.

The test statistic is again a \(\chi^2\) value, which compares the observed and expected counts; the expected counts are found in the same way as in Sect. 35.3.1. For two-way tables larger than \(2\times 2\) (see Sect. 35.7), the parameter describing the association between the variables is the \(\chi^2\) value itself. When no relationship exists in the sample, the observed and expected values are the same, and \(\chi^2 = 0\). The larger the difference between the observed and expected values, the larger the value of \(\chi^2\). Sampling variation means that the observed values will vary from sample to sample, so that \(\chi^2\) may not be exactly zero, even if there is no association between the variables.

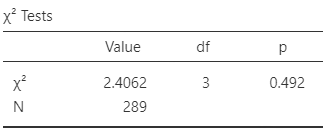

Software computes \(\chi^2 = 2.406\) (Fig. 35.3). The two-tailed \(P\)-value is (Fig. 35.3, left panel) \(P = 0.492\).

For comparing more than two odds or proportions, the alternative hypothesis is always two-tailed.

FIGURE 35.3: Software output for the hypothesis test about knowledge of ocean rips.

The statistical validity conditions are the same as in Sect. 35.4: all expected counts are at least five. The test is statistically valid (Fig. 35.3, right panel).

Click on the hotspots in the following image, and describe what the jamovi output tells us.

35.6 Example: turtle nests

(This study was seen in Sect. 28.6.) The hatching success of loggerhead turtles on Mediterranean beaches is often compromised by fungi and bacteria. Candan, Katılmış, and Ergin (2021) compared the odds of a nest being infected, between nests relocated due to the risk of tidal inundation, and non-relocated nests (Table 35.7). The researchers were interested in knowing:

For Mediterranean loggerhead turtles, are the odds of infections the same for natural and relocated nests?

| Non-infected | Infected | |

|---|---|---|

| Natural | \(29\) | \(10\) |

| Relocated | \(14\) | \(\phantom{0}8\) |

The corresponding hypotheses can be written using proportion, after defining \(p\) as the proportion of nests that are infected:

- \(H_0\): \(p_N - p_R = 0\) (equivalent to \(p_N = p_R\)); and

- \(H_1\): \(p_N - p_R \ne 0\) (equivalent to \(p_N \ne p_R\)),

where \(N\) refers to Natural nests, and \(R\) to Relocated nests. The parameter is the odds difference between the population proportion.

The hypotheses can also be written using odds:

- \(H_0\): The odds of a nest being infected is the same for natural and relocated nests; and

- \(H_1\): The odds of a nest being infected is not the same for natural and relocated nests.

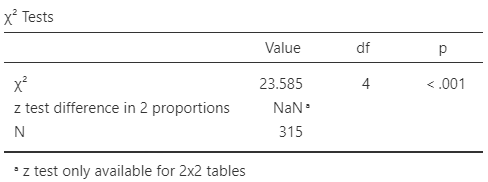

The parameter is the odds ratio of infection, comparing natural to relocated nests.

A graphical summary is shown in Fig. 28.3. A numerical summary table (Table 28.3, right table) shows that the odds of natural nest being infected is \(1.657\) times the odds of a relocated nest being infected. From the software output (Fig. 35.4), the \(\chi^2\)-value is \(0.777\). This is like a \(z\)-score of \(z = \sqrt{0.777/1} = 0.88\), which is very small, so expect a large \(P\)-value. (Notice that this is the value of the \(z\)-score shown in Fig. 35.4 for comparing two proportions.) The \(P\)-value is \(0.378\) on the output (for both tests).

The smallest expected count is \(22\times 18 / 61 = 6.49\), which exceeds five, so these tests are statistically valid. We write:

There is no evidence of a difference in the odds of infection (\(\chi^2\): \(0.777\); \(P\)-value: \(0.378\); odds ratio: \(1.657\) (\(95\)% CI: \(0.537\) to \(5.12\))) between natural nests (odds: \(2.90\); \(n = 39\)) and relocated nests (odds: \(1.75\); \(n = 22\)).

The conclusion could also be written in terms of proportions:

There is no evidence of a difference in the proportion of infection (difference between proportions: \(0.108\) (\(95\)% CI from \(-0.136\) to \(0.527\)); \(z = 0.882\); \(P\)-value: \(0.378\)) between natural nests (\(p = 0.744\); \(n = 39\)) and relocated nests (\(p = 0.636\); \(n = 22\)).

Either way, there no evidence that relocating the nest (to protect them from tidal inundation) changes the risk of infection.

We do not say whether the evidence supports the null hypothesis. We assume the null hypothesis is true, so we state how strong the evidence is to change outr mind (and hence support the alternative hypothesis). The current sample presents no evidence to contradict the assumption, but future evidence may emerge.

FIGURE 35.4: The software output for the turtle-nesting data.

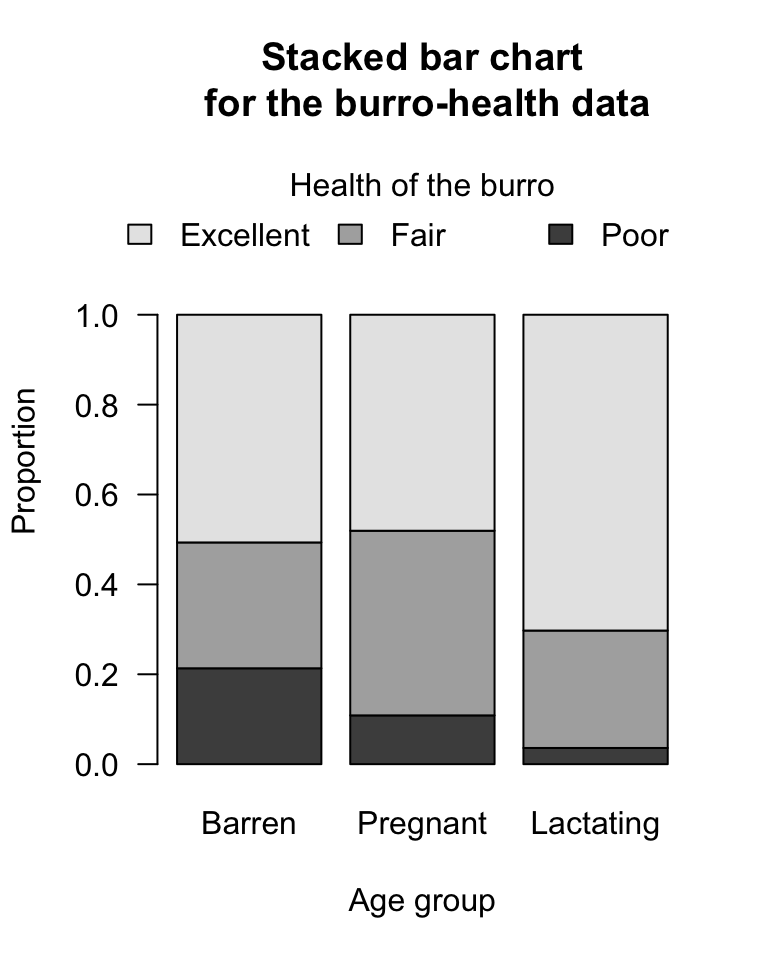

35.7 Example: health of female burros

R. A. Johnson, Carothers, and McGill (1987) studied \(315\) introduced female burros (donkeys) in the Mojave Desert (California) to understand management processes. One RQ was:

For these female burros, is the reproductive status of the burros related to their health?

The data (Table 35.8) are given in a \(3\times 3\) table of counts. The data are summarised using row proportions in Table 35.9), and in a graph in Fig. 35.5 (left panel). Software output is shown in Fig. 35.5 (right panel). (Odds could be produced in the numerical summary also, but odds ratios are trickier since they require comparing pairs of odds.)

| Excellent | Fair | Poor | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Barren | \(\phantom{0}16\) | \(\phantom{0}21\) | \(\phantom{0}38\) |

| Pregnant | \(\phantom{0}14\) | \(\phantom{0}53\) | \(\phantom{0}62\) |

| Lactating | \(\phantom{0}\phantom{0}4\) | \(\phantom{0}29\) | \(\phantom{0}78\) |

| Odds | Odds ratio | Percentage | \(n\) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barren | \(0.271\) | \(7.254\) | \(21.333\) | \(75.000\) |

| Pregnant | \(0.122\) | \(3.257\) | \(10.853\) | \(129.000\) |

| Lactating | \(0.037\) | \(3.604\) | \(111.000\) |

FIGURE 35.5: Left: a stacked bar chart for the burro-health data. Right: software output for the burro-health data.

The hypothesis are usually worded in terms of associations (or relationships):

- \(H_0\): No association exists between reproductive status and overall health.

- \(H_1\): An association exists between reproductive status and overall health.

From the software output (Fig. 35.5, right panel), \(\chi^2 = 23.585\). Notice that a comparison of proportions is not possible for tables larger than \(2\times 2\). Software reports \(P < 0.001\), which suggests very strong evidence in the sample that an association exists between reproductive status and overall health.

The conclusion could be written as

The sample provides very strong evidence (\(\chi^2 = 23.585\)) of an association between reproductive status and overall health of female burros (\(n = 315\)).

Adding sample summary information to this conclusion is cumbersome. Instead, readers can be pointed to the numerical summary (Table 35.9). Furthermore, CIs are not reported since software does not always produce CIs for tables larger than \(2\times 2\).

While we know there is an association between the variables, we can only speculate on the nature of the association (i.e., for which group(s) the population proportions are different). Doing so requires methods beyond this book.

The smallest expected value is \(75\times 34/315 = 8.1\), which exceeds \(5\), so the results are statistically valid.

35.8 Chapter summary

To test a hypothesis about a difference between two population proportions \(p_A - p_B\):

- Write the null hypothesis (\(H_0\)) and the alternative hypothesis (\(H_1\)).

- Initially assume the value of \((p_A - p_B)\) in the null hypothesis to be true.

- Then, describe the sampling distribution, which describes what to expect from the difference between the sample proportions based on this assumption: under certain statistical validity conditions, the difference between the sample proportions vary with:

- an approximate normal distribution,

- with sampling mean whose value is the value of \((p_A - p_B)\) (from \(H_0\)), and

- having a standard deviation of \(\displaystyle \text{s.e.}(\hat{p}_A - \hat{p}_B)\).

- Compute the value of the test statistic: \[ z = \frac{ (\hat{p}_A - \hat{p}_B) - (p_A - p_B)}{\text{s.e.}(\hat{p}_A - \hat{p}_B)}, \] where \(p_A - p_B\) is the hypothesised difference given in the null hypothesis.

- The \(t\)-value is like a \(z\)-score, and so an approximate \(P\)-value can be estimated using the \(68\)--\(95\)--\(99.7\) rule, or found using software.

- Make a decision, and write a conclusion.

To test a hypothesis for comparing two odds, or to test for a relationship between two qualitative variables more generally:

- Write the null hypothesis (\(H_0\)) and the alternative hypothesis (\(H_1\)).

- Initially assume no relationship between the two variables.

- Find the value of the test statistic (a \(\chi^2\)-score) on the software output. (For \(2\times 2\) tables only, the equivalent \(z\)-score is \(\sqrt{\chi^2}\).

- A \(P\)-value is found using software.

- Make a decision, and write a conclusion.

- Check the statistical validity conditions.

35.9 Quick review questions

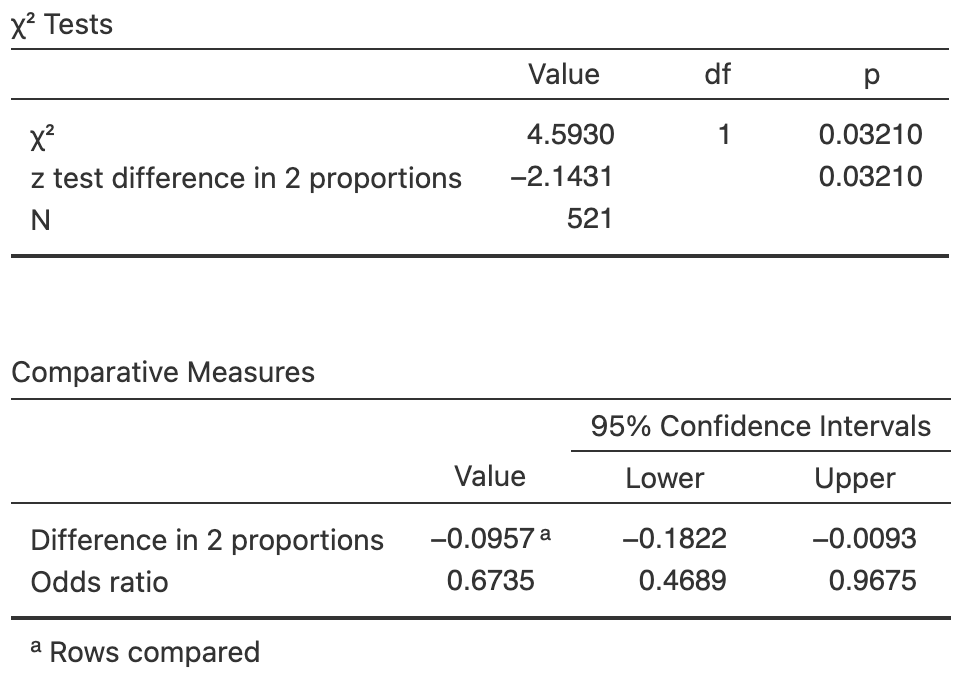

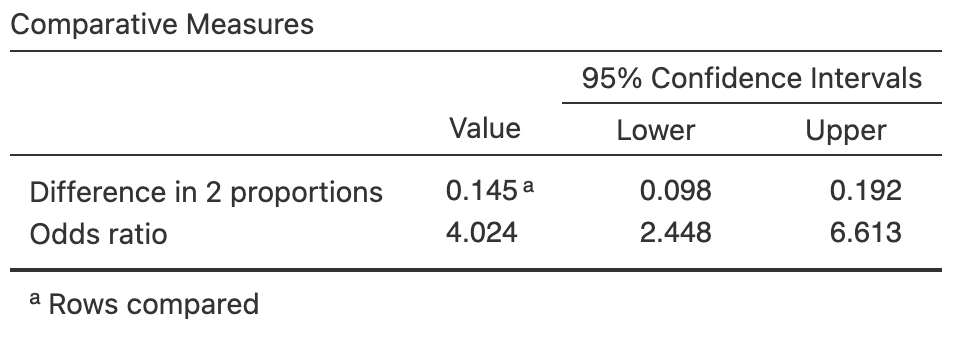

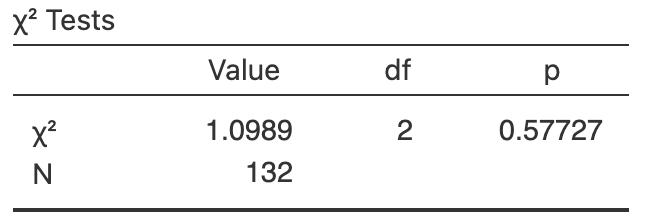

Meresa, Tadesse, and Zeray (2023) investigated Ethiopian farmers' adoption of improved soil and water conservation structures on their farms (Table 35.10). Software output is shown in Fig. 35.6.

| Non-adopter | Adopter | |

|---|---|---|

| \(< 0.5\) ha | \(86\) | \(61\) |

| \(\ge 0.5\) ha | \(43\) | \(71\) |

FIGURE 35.6: Software output for the farming study.

- What is the \(\chi^2\) value?

- What is the equivalent \(z\)-score (to two decimal places)?

- Using the \(68\)--\(95\)--\(99.7\) rule, what is the approximate \(P\)-value?

- From the software output, what is the \(P\)-value?

- Is the alternative hypothesis one- or two-tailed?

- True or false: There is no evidence of a difference in odds of adopting of conservation practices, for the two far size categories.

- True or false: The test will be statistically valid.

35.10 Exercises

Answers to odd-numbered exercises are available in App. E.

Exercise 35.1 Consider the expected counts in Table 35.4. Confirm that the odds of having most meals off-campus is the same for students living with their parents, and for students not living with their parents.

Exercise 35.2 Consider the expected counts in Fig. 35.6. Confirm that the odds of being an adopter of improved soil and water conservation structures is the same for smaller and larger farms.

Exercise 35.3 Suppose an analysis of a \(2\times 2\) table of counts produces a value of \(\chi^2 = 10.66\).

- What would be the equivalent \(z\)-score for comparing the two proportions?

- What would be the approximate \(P\)-value?

Exercise 35.4 Suppose an analysis of a \(2\times 2\) table of counts produces a value of \(\chi^2 = 4.06\).

- What would be the equivalent \(z\)-score for comparing the two proportions?

- What would be the approximate \(P\)-value?

Exercise 35.5 Christensen, Herrer, and Telford (1972) studied the number of sandflies caught in light traps set at \(3\) and \(35\) feet above ground in eastern Panama. They asked:

In eastern Panama, are the odds of finding a sandfly that is male the same at \(3\) feet above ground as at \(35\) feet above ground?

The data are shown in Table 35.11.

- Compile a numerical summary table.

- Sketch an appropriate graph to summarise the data.

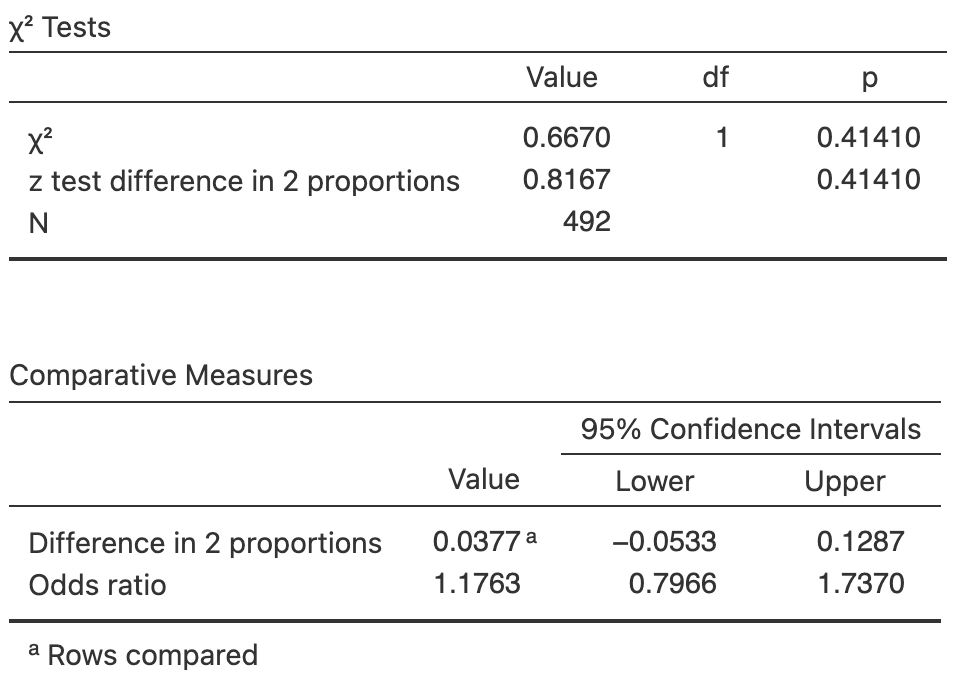

- Use the software output (Fig. 35.7) to evaluate the evidence and write a conclusion.

- Is the test statistically valid?

| Males | Females | |

|---|---|---|

| 3 feet above ground | \(173\) | \(150\) |

| 35 feet above ground | \(125\) | \(\phantom{0}73\) |

FIGURE 35.7: Software output for the sandflies data.

Exercise 35.6 (This study also appeared in Exercise 28.4.) Wallace et al. (2017) compared the heights of scars from burns received in Western Australia (Table 28.7). The data are shown in Table 35.12. Software was used to analyse the data (Fig. 35.8).

- Compile a numerical summary table.

- Sketch an appropriate graph to summarise the data.

- Use the software output to evaluate the evidence and write a conclusion.

- Is the test statistically valid?

| 0(smooth) | Between 0and 1 | |

|---|---|---|

| Women | \(99\) | \(\phantom{0}62\) |

| Men | \(216\) | \(115\) |

FIGURE 35.8: Software output for the scar-height data.

Exercise 35.7 (This study also appeared in Exercise 28.9.) A study of turbine failures (Myers, Montgomery, and Vining 2002; Nelson 1982) ran \(73\) turbines for around \(1800\), and found that seven developed fissures (small cracks). They also ran a different set of \(42\) turbines for about \(3000\), and found that nine developed fissures.

FIGURE 35.9: Software output for the turbine data.

Exercise 35.8 [Daatset: EmeraldAug]

(This study also appeared in Exercise 28.8.)

The Southern Oscillation Index (SOI) is a standardised measure of the air pressure difference between Tahiti and Darwin, and has been shown to be related to rainfall in some parts of the world (Stone, Hammer, and Marcussen 1996), and especially Queensland (Stone and Auliciems 1992).

The rainfall at Emerald (Queensland) was recorded for Augusts between 1889 to 2002 inclusive (P. K. Dunn and Smyth 2018), where the monthly average SOI was positive, and when the SOI was non-positive (that is, zero or negative), as shown in Table 35.13.

- Using the software output in Fig. 35.10, perform a hypothesis test to determine if the odds of having no rain is the same Augusts with non-positive and negative SOI.

- Write down the conclusion.

- Is the test statistically valid?

| Rainfall recorded | No rainfall recorded | |

|---|---|---|

| Positive SOI | \(53\) | \(\phantom{0}7\) |

| Non-positive SOI | \(40\) | \(14\) |

FIGURE 35.10: Software output for the Emerald-rain data.

Exercise 35.9 [Dataset: HatSunglasses]

(This study also appeared in Exercise 28.10.)

B. Dexter et al. (2019) recorded the number of people at the foot of the Goodwill Bridge, Brisbane, who wore hats between \(11\):\(30\)am to \(12\):\(30\)pm.

Of the \(386\) males observed, \(79\) wore hats; of the \(366\) females observed, \(22\) wore hats.

- Compute the percentages of females wearing a hat.

- Compute the percentages of males wearing a hat.

- Compute the odds of a female wearing a hat.

- Compute the odds of a male wearing a hat.

- Compute the odds ratio of wearing a hat, comparing females to males.

- Compute the odds ratio of wearing a hat, comparing males to females.

- Find the \(95\)% CI for the appropriate OR.

- Using the software output in Fig. 35.11, perform a hypothesis test to determine if the odds of wearing a hat is the same for females and males.

- Write down the conclusion.

- Is the test statistically valid?

FIGURE 35.11: Software output for the hats data.

Exercise 35.10 Witmer and Pipas (2020) compared various types of repellents to stop bears damaging trees in an Idaho forest. Part of the data are summarised in Table 35.14.

- Compute the column percentages.

- Compute the odds of new damage for both repellents.

- Compute the proportion of trees with new damage.

- Compute the odds ratio, and the difference between the proportions.

- Write the hypothesis for conducting a hypothesis test.

- Compute the expected counts.

- Software gives \(\chi^2\) is \(4.4850\). What is the equivalent \(z\)-score? Would you expect a large or small \(P\)-value?

- The \(P\)-value is given as \(P = 0.0342\). Write a conclusion.

| New damage | No new damage | |

|---|---|---|

| Bear faeces | \(\phantom{0}6\) | \(69\) |

| Control (water) | \(15\) | \(60\) |

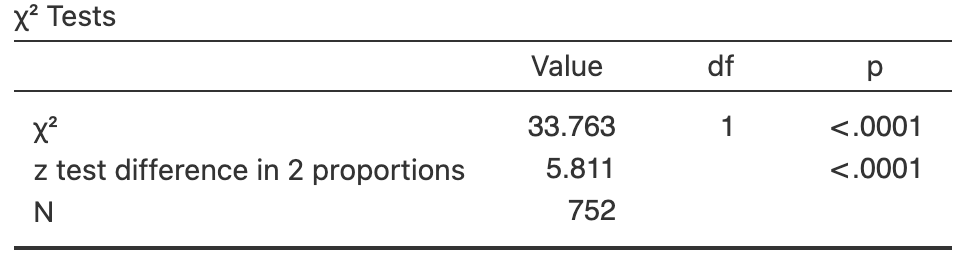

Exercise 35.11 [Dataset: PetBirds]

(This study also appeared in Exercise 28.11.)

Kohlmeier et al. (1992) examined people with lung cancer, and a matched set of controls who did not have lung cancer, and recorded the number in each group that kept pet birds.

The data are shown again in Table 35.15, and the software output in Fig. 35.12.

Consider this RQ:

Are the odds of having a pet bird the same for people with lung cancer (cases) and for people without lung cancer (controls)?

- Carefully describe the parameter.

- Write the hypotheses in terms of odds.

- Determine the value of \(z\) that is approximately the same as this \(\chi^2\)-value.

- Use the software output to conduct a hypothesis test.

| Adults with lung cancer | Adults without lung cancer | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Did not keep pet birds | \(141\) | \(328\) | \(469\) |

| Kept pet birds | \(\phantom{0}98\) | \(101\) | \(199\) |

| Total | \(239\) | \(429\) | \(668\) |

FIGURE 35.12: Software output for the pet-birds data.

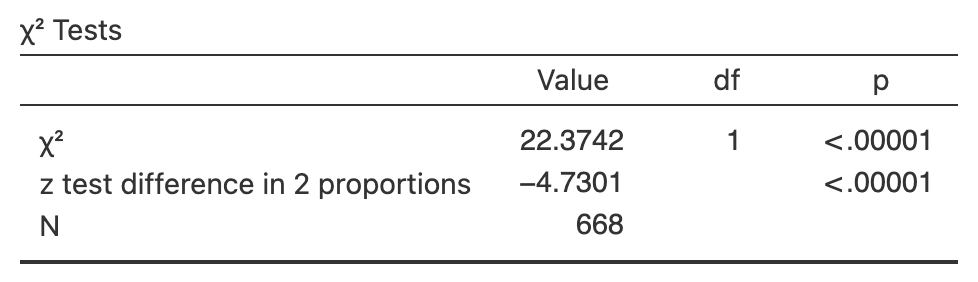

Exercise 35.12 [Dataset: B12Diet]

(This study was seen in Exercise 28.12.)

Gammon et al. (2012) examined B12 deficiencies in 'predominantly overweight/obese women of South Asian origin living in Auckland', some of whom were on a vegetarian diet and some of whom were on a non-vegetarian diet.

One RQ was:

Among a certain group of women, are the odds of being vitamin B12 deficient different for women on a vegetarian diet compared to women on a non-vegetarian diet?

The data are shown in Table 28.10.

- Write down the hypotheses in terms of odds.

- Write down the parameter.

- Determine the \(\chi^2\) value and perform a hypothesis to answer the RQ, using the output in Fig. 35.13.

- Compute the equivalent \(z\)-score for this \(\chi^2\)-value.

- Write down the conclusion.

- Is the test statistically valid?

FIGURE 35.13: Software output for the B12 data.

Exercise 35.13 [Dataset: DogWalks]

Naughton, Grzelak, and Naughton (2024) studied the difference between dogs kept in the city and on farms.

One RQ was:

For Northern Ireland dogs, is there an association between length of dog walks, and their location?

The data are shown in Table 35.16.

- Write down the hypotheses.

- Determine the \(\chi^2\) value and perform a hypothesis to answer the RQ, using the output in Fig. 35.14.

- Write down the conclusion.

- Is the test statistically valid?

| Under \(30\) | \(30\) to under \(60\) | \(60\) to under \(120\) | Varies | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| City | \(138\) | \(\phantom{0}84\) | \(\phantom{0}13\) | \(264\) |

| Farm | \(\phantom{0}84\) | \(102\) | \(\phantom{0}33\) | \(243\) |

FIGURE 35.14: Software output for the dog-walking data.

Exercise 35.14 [Dataset: Mumps]

Soud et al. (2009) studied the compliance of students with an isolation request following a large mumps outbreak in Kansas in 2006.

One RQ was:

Is there an association between age group, and compliance with the isolation order?

The data are shown in Table 35.17 and the software output in Fig. 35.15.

- Write down the hypotheses.

- Compute the proportion of each age group that complied with the isolation request.

- Compute the odds of each age group that complied with the isolation request.

- Compute the relevant odds ratios, and interpret what these mean.

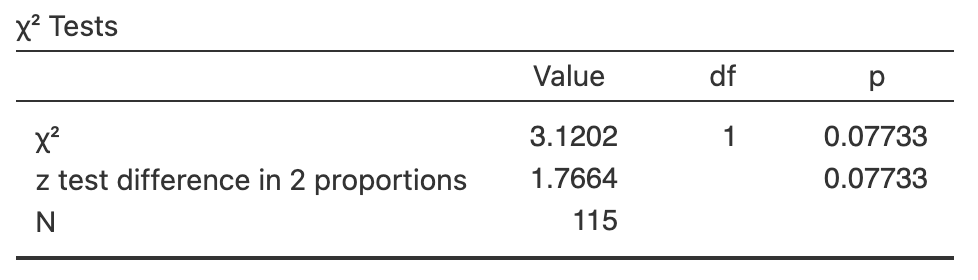

- Determine the \(\chi^2\) value and perform a hypothesis to answer the RQ, using the software output.

- Write down the conclusion.

- Is the test statistically valid?

35.10.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.1

| Complied | Did not comply | |

|---|---|---|

| \(18\) to \(19\) | \(40\) | \(10\) |

| \(20\) to \(21\) | \(37\) | \(14\) |

| Older than \(22\) | \(22\) | \(\phantom{0}9\) |

FIGURE 35.15: Software output for the compliance data.

35.10.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.1.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.1

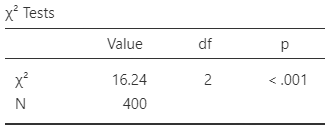

Exercise 35.15 [Dataset: ShoppingBags]

Choon, Tan, and Chong (2017) studied \(400\) residents of Klang Valley, Malaysia, to examine residents' approach to waste management.

One RQ was:

For residents of Klang Valley, is age group associated with whether people bring their own bags when shopping?

The data (Table 35.18) are given in a \(3\times 2\) table of counts. The software output is shown in Fig. 35.16.

35.10.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.2

| Brings own bags | Does not bring own bags | |

|---|---|---|

| \(30\) and under | \(126\) | \(138\) |

| \(31\) to \(40\) | \(\phantom{0}50\) | \(\phantom{0}32\) |

| Over \(40\) | \(\phantom{0}41\) | \(\phantom{0}13\) |

FIGURE 35.16: Software output for the shopping-bags data.

35.10.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.2.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.1

- Compute the odds of someone bringing a shopping bag, for each age group.

- Compute the odds ratio of bringing a shopping bag (using the 'Over \(40\)' age group as the reference level).

- Compute the percentage of people bringing a shopping bag, for each age group.

- Construct the hypotheses for testing for an association between the variables.

- Use the software output to answer the research question.

- Write a conclusion.

- Is the test statistically valid.

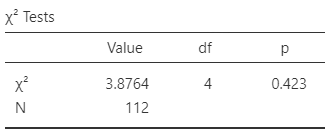

Exercise 35.16 [Dataset: CrabShell]

Hermit crabs place sea anemones on their shells for protection.

Brooks (1989) studied the placement of the anemones:

Is there a relationship between the vertical and horizontal locations of anemones placed by hermit crabs on their shells?

The data are shown in Table 35.19, and output in Table 35.17. Perform a hypothesis test to answer the RQ.

35.10.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.3

| Side 1 | Central | Side 2 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Side 1 | \(\phantom{0}\phantom{0}2\) | \(\phantom{0}\phantom{0}9\) | \(\phantom{0}\phantom{0}9\) |

| Central | \(\phantom{0}22\) | \(\phantom{0}30\) | \(\phantom{0}37\) |

| Side 2 | \(\phantom{0}\phantom{0}1\) | \(\phantom{0}\phantom{0}0\) | \(\phantom{0}\phantom{0}2\) |

FIGURE 35.17: Software output for the crab-shell data.

35.10.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.3.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.1