38 Regression

So far, you have learnt about the research process, including analysing data using confidence intervals and hypothesis tests.

In this chapter, you will learn to:

- produce and interpret linear regression equations.

- conduct hypothesis tests for the slope in a regression line.

- produce confidence intervals for the slope in a regression line.

38.1 Introduction

Chapters 16 and 37 studied correlation, which measures the strength of the linear relationship between two quantitative variables \(x\) (an explanatory variable) and \(y\) (a response variable). We now study regression, which describes what the linear relationship is between \(x\) and \(y\). The relationship is described mathematically, using an equation, which allows us to:

- Predict values of \(y\) from given values of \(x\) (Sect. 38.4); and

- Understand the relationship between \(x\) and \(y\) (Sect. 38.5).

An example of a linear regression equation, that describes the relationship between the observed values of an explanatory variable \(x\) and the observed values of a response variable \(y\), is \[\begin{equation} \hat{y} = -4 + (2\times x), \qquad\text{usually written}\qquad \hat{y} = -4 + 2x. \tag{38.1} \end{equation}\] The notation \(\hat{y}\) refers to the mean of all the \(y\) values that could be observed for some given value of \(x\). That is, for some value of \(x\), many values of \(y\) could be observed, and \(\hat{y}\) is the value that regression equation predicts as the mean of all those possible values.

\(y\) refers to the values of the response variable observed from individuals. \(\hat{y}\) refers to mean predicted value of \(y\) for given values of \(x\).

\(\hat{y}\) is pronounced as 'why-hat'; the 'caret' above the \(y\) is called a 'hat'.

More generally, the equation of a straight line is \[ \hat{y} = b_0 + (b_1 \times x), \qquad\text{usually written}\qquad \hat{y} = b_0 + b_1 x, \] where \(b_0\) and \(b_1\) are (unknown) numbers estimated from sample data. Notice that \(b_1\) is the number multiplied by \(x\). In Eq. (38.1), \(b_0 = -4\) and \(b_1 = 2\).

Example 38.1 (Regression equations) A report on the growth of Australian children (Pfizer Australia 2008) found an approximate linear relationship between the age of girls in years \(x\) and their height in cm \(y\) for girls between four and seven years of age. The regression equation was approximately \[ \hat{y} = 73 + 7x. \] In this equation, \(b_0 = 73\) and \(b_1 = 7\). The regression equation predicts the mean height for any given age \(x\). Some individual girls aged \(7\) will be taller than predicted, and some will be shorter.

The regression equation is the same when written as \[ \hat{y} = 7x + 73. \]

38.2 Linear equations: review

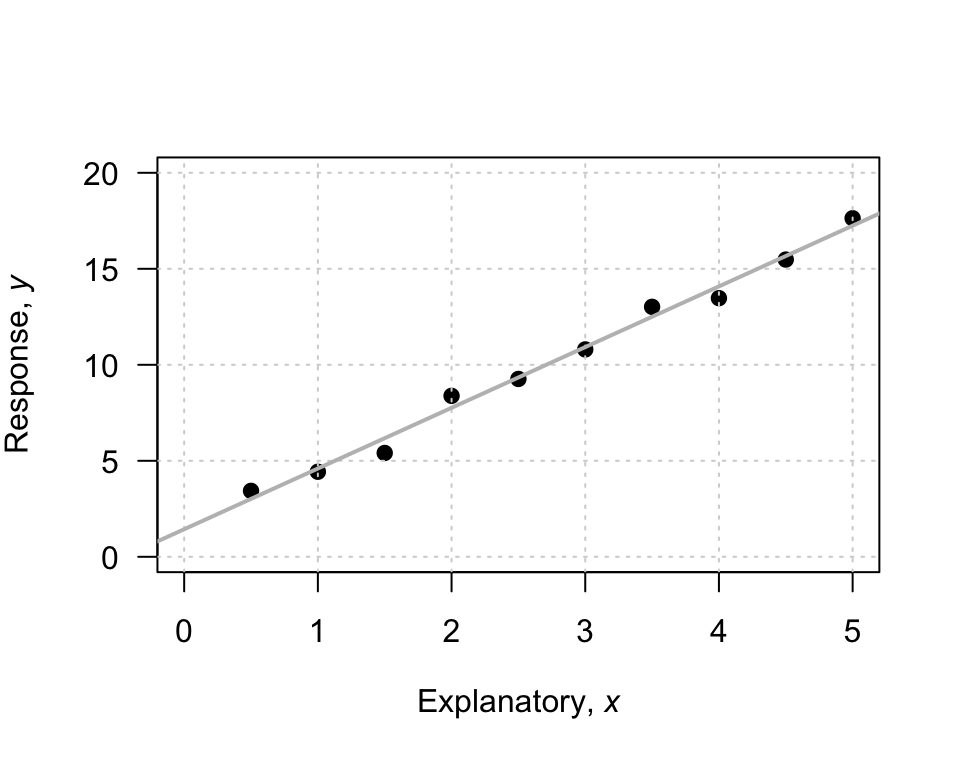

To introduce, or revise, the idea of a linear equation, consider the (artificial) data in Fig. 38.1, with an explanatory variable \(x\) and a response variable \(y\). In the graph, I have drawn a sensible line on the graph that seems to capture the relationship between \(x\) and \(y\). The line describes the predicted mean values of \(y\) for various values of \(x\). A regression equation is used to describe the line. In the regression equation \(\hat{y} = b_0 + b_1 x\), the numbers \(b_0\) and \(b_1\) are called regression coefficients, where

- \(b_0\) is the intercept or the \(y\)-intercept. Its value corresponds to the predicted mean value of \(y\) when \(x = 0\).

- \(b_1\) is the slope. It measures how much the value of \(y\) changes, on average, when the value of \(x\) increases by \(1\).

We will use software to find the values of \(b_0\) and \(b_1\) (the formulas are tedious to use). However, a rough approximation of the value of \(b_0\) and \(b_1\) can be obtained by first drawing a sensible-looking straight line through the scatterplot of the data (Fig. 38.1).

A rough approximation of the value of the intercept \(b_0\) is the value of \(\hat{y}\) from the drawn line when \(x = 0\). When \(x = 0\), the regression line suggests the value of \(\hat{y}\) is about \(2\); that is, the value of \(b_0\) is approximately \(2\).

A rough approximation of the slope \(b_1\) is found by computing \[ \frac{\text{Change in $y$}}{\text{Corresponding \emph{increase} in $x$}} = \frac{\text{rise}}{\text{run}} \] from the drawn line. This approximation of the slope is the change in the value of \(y\) (the 'rise') divided by the corresponding increase in the value of \(x\) (the 'run').

FIGURE 38.1: An example scatterplot.

Consider what happens in the animation below when the value of \(x\) increases from \(1\) to \(5\) (an increase of \(5 - 1 = 4\)). The corresponding values of \(y\) change from \(5\) to \(17\), a change (specifically, an increase) of \(17 - 5 = 12\). So: \[ \frac{\text{rise}}{\text{run}} = \frac{17 - 5}{5 - 1} = \frac{12}{4} = 3. \] The value of \(b_1\) is about \(3\). The regression line is approximately \(\hat{y} = 2 + (3\times x)\), usually written \[ \hat{y} = 2 + 3x. \]

The regression equation has \(\hat{y}\) (not \(y\)) on the left-hand side. That is, the equation predicts the mean values of \(y\), which may not be equal to the observed values (which are denoted by \(y\)).

A 'good' regression equation would produce predicted values \(\hat{y}\) close to the observed values \(y\); that is, the line passes close to each point on the scatterplot.

The intercept \(b_0\) has the same measurement units as the response variable. The measurement unit for the slope \(b_1\) is the 'measurement units of the response variable', per 'measurement units of the explanatory variable'.

Example 38.2 (Measurement units of regression parameters) In Example 38.1, the regression line for the relationship between the age of Australian girls in years \(x\) and their height (in cm) \(y\) was \(\hat{y} = 73 + 7x\) (for girls between four and seven years).

In this equation, the intercept is \(b_0 = 73\)and the slope is \(b_1 = 73\)/year.

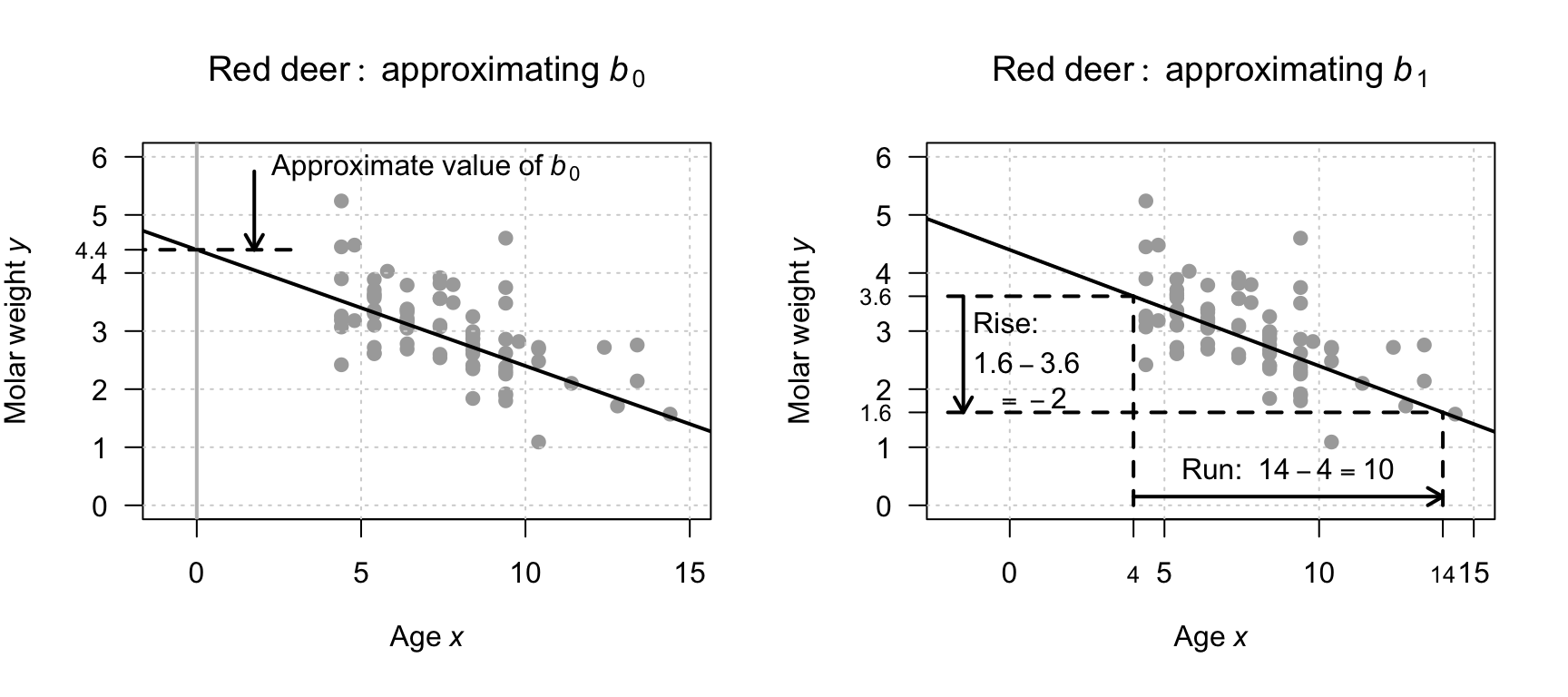

Example 38.3 (A rough approximation of the regression equation) For the red-deer data used in the previous chapters (Fig. 37.1), a rough estimate of the regression line can be drawn on a scatterplot to estimate \(b_0\) and \(b_1\) (Fig. 38.2). The estimate of \(b_0\) is roughly \(4.4\).

The estimate of \(b_1\) can be found using the 'rise-over-run' idea. When \(x = 4\), the value of \(\hat{y}\) (according to the drawn line) is about \(3.6\); similarly, when the value of \(x\) increases to \(14\), the value of \(\hat{y}\) reduces to about \(1.6\). That is, for a 'run' of \(14 - 4 = 10\), the 'rise' is \(1.6 - 3.6 = -2.0\), and so a rough estimate of the slope is \(-2/10 = -0.2\). This is a negative rise (i.e., a fall), since the value of \(y\) is smaller as the value of \(x\) increases. (The relationship is negative, so the slope is negative.)

The rough guess of the regression line is therefore \[ \hat{y} = 4.4 - 0.2x, \] where \(x\) is the age (in years), and \(y\) is molar weight (in g). The rough guess of the intercept \(b_0\) is \(4.4\), while the rough guess of the slope \(b_1\) is \(-0.2\)/year.

FIGURE 38.2: Obtaining rough guesses for the regression equation for the red-deer data. Left: approximating \(b_0\). Right: approximating \(b_1\) using rise-over-run.

You may like the following interactive activity, which explores slopes and intercepts.

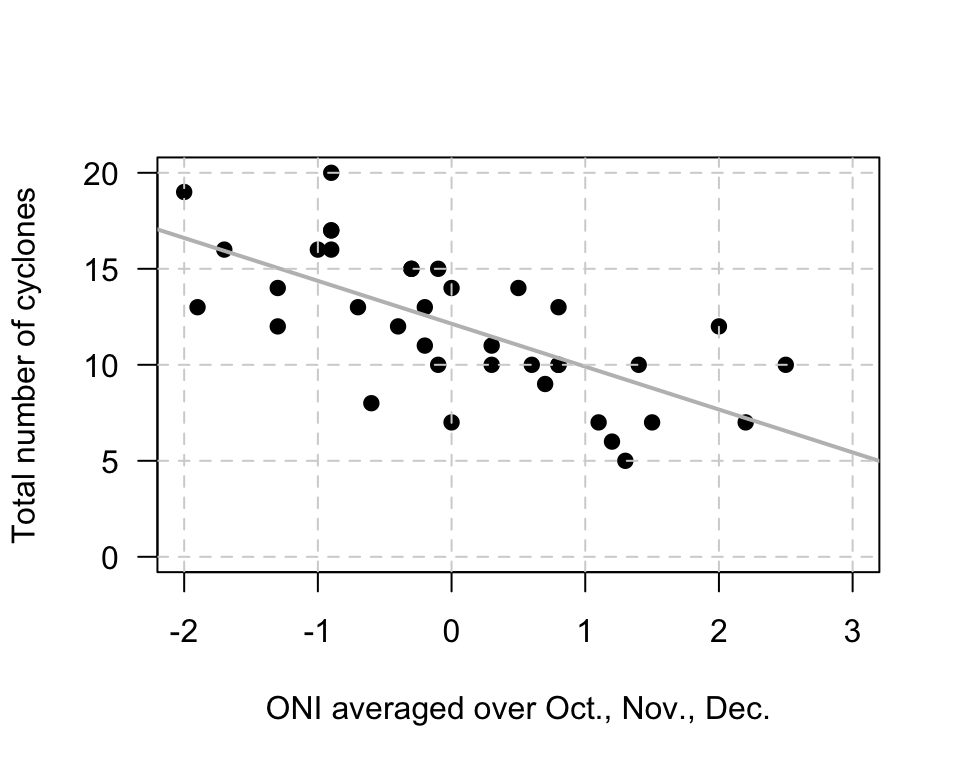

Example 38.4 (Estimating regression parameters) The relationship (P. K. Dunn and Smyth 2018) between the number of cyclones \(y\) in the Australian region each year from 1969 to 2005, and a climatological index called the Ocean Niño Index (ONI, \(x\)), is shown in Fig. 38.3.

When the value of \(x\) is zero, the predicted value of \(y\) is about \(12\), so \(b_0\) is about \(12\). Notice that the intercept is the predicted value of \(y\) when \(x = 0\), which is not at the left of the graph in Fig. 38.3.

To approximate the value of \(b_1\), use the 'rise-over-run' idea. When \(x\) is about \(-2\), the predicted mean value of \(y\) is about \(17\); when \(x\) is about \(2\), the predicted mean value of \(y\) is about \(8\). The value of \(x\) increases by \(2 - (-2) = 4\), while the value of \(y\) changes by \(8 - 17 = -9\) (a decrease of about \(9\)). Hence, \(b_1\) is approximately \(-9/4 = -2.25\). (You may get something slightly different.)

The relationship has a negative direction, so the slope must be negative. The regression line is approximately \(\hat{y} = 12 - 2.25x\).

FIGURE 38.3: The number of cyclones in the Australian region each year from 1969 to 2005, and the ONI averaged over October, November, December.

The above method gives a crude approximation to the values of the intercept \(b_0\) and the slope \(b_1\). In practice, many reasonable lines could be drawn through a scatterplot of data. However, one of those lines is the 'best' line in some sense9. Software calculates this 'line of best fit'.

38.3 Fitting regression equations using software

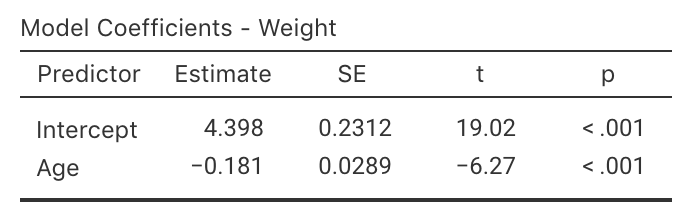

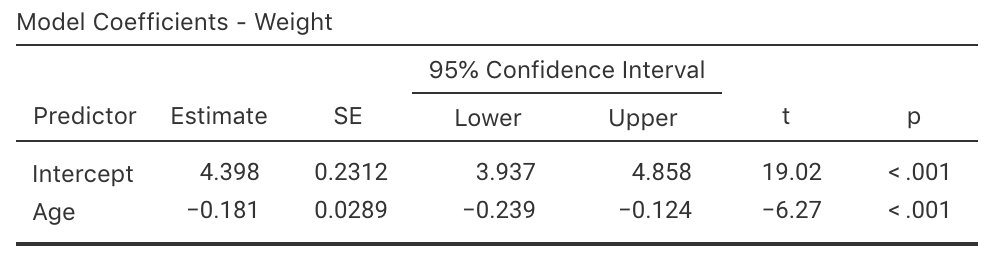

For the red-deer data again (Fig. 37.1), part of the relevant software output is shown in Fig. 38.4.

The values of \(b_0\) and \(b_1\) are in the column labelled Estimate in the output; the value of the sample slope is \(b_1 = -0.181\), and the value of the sample \(y\)-intercept is \(b_0 = 4.398\):

These are the values of the two regression coefficients.

The regression equation is

\[

\hat{y} = 4.398 + (-0.181\times x),

\qquad\text{usually written as}\qquad

\hat{y} = 4.398 - 0.181 x.

\]

These are close to the values obtained using the rough method in Sect. 38.2 (where \(b_0 = 4.4\) and \(b_1 = -0.2\) approximately).

The sign of the slope \(b_1\) and the sign of correlation coefficient \(r\) are always the same. For example, if the slope is negative, the correlation coefficient will also be negative.

FIGURE 38.4: The software output for the red-deer data.

Example 38.5 (Regression coefficients) The regression equation for the cyclone data (Fig. 38.3) is found from the software output (Fig. 38.5): \[ \hat{y} = 12.14 - 2.23x, \] where \(x\) is the ONI (averaged over October, November, December) and \(y\) is the number of cyclones; that is, \(b_0 = 12.14\) and \(b_1 = -2.23\). These values are close the approximations made in Example 38.4 (\(b_0 = 12\) and \(b_1 = -2.25\) respectively).

FIGURE 38.5: The software output for the cyclone data.

You may like the following interactive activity, which explores regression equations.

38.4 Using regression equations for making predictions

The regression equation for the red-deer data, estimated from one of the many possible samples, is \(\hat{y} = 4.398 - 0.181 x\), and can be used to make predictions of the mean value of \(y\) for a given value of \(x\). For example, the equation can be used to predict the average molar weight for \(10\)-year-old male red deer. Since \(x\) represents the age, use \(x = 10\) in the regression equation: \[\begin{align*} \hat{y} &= 4.398 - (0.181\times 10)\\ &= 4.398 - 1.81 = 2.588. \end{align*}\] Male red deer \(10\) years old are predicted to have a mean molar weight of \(2.588\). Some individual deer aged \(10\) will have molars weighing more than this, and some weighing less than this; the model predicts that the mean molar weight for male red deer aged \(10\) will be about \(2.588\).

The value of \(\hat{y}\) is computed using the estimates \(b_0\) and \(b_1\), which are computed from sample data. Hence, the value of \(\hat{y}\) is also depends on which one of the countless possible samples is used. This means that \(\hat{y}\) also has a standard error.

Suppose we were interested in male red deer \(20\) years of age; the mean predicted weight of the molars is \[ \hat{y} = 4.398 - (0.181 \times 20) = 0.778, \] or about \(0.78\). This prediction may be a useful prediction, but it also may be rubbish. In the data, the oldest deer is aged \(14.4\) years, so the regression line may not even apply for deer aged over \(14.4\) years of age. For example, the relationship may be non-linear after \(14\) years of age, or red deer may not even live to \(20\) years of age. The prediction may be sensible, but it may not be either. We don't know whether the prediction is sensible or not, because we have no data for deer aged over \(14.4\) years to inform us.

Making predictions outside the range of the available data is called extrapolation, and extrapolation beyond the data may lead to nonsense predictions. As an extreme example, deer aged \(25\) would be predicted to have a mean molar weight of \(-0.127\), which is clearly nonsense (molars cannot have a negative weight).

Definition 38.1 (Extrapolation) Extrapolation refers to making predictions outside the range of the available data. Extrapolation beyond the data may lead to nonsense predictions.

38.5 Using regression equations for understanding relationships

The regression equation can be used to understand the relationship between the two variables.

Consider again the red-deer regression equation (from Sect. 38.3):

\[\begin{equation}

\hat{y}

=

4.398

-

0.181 x.

\tag{38.2}

\end{equation}\]

What does this equation reveal about the relationship between \(x\) and \(y\)?

38.5.1 The meaning of \(b_0\)

\(b_0\) is the predicted value of \(y\) when \(x = 0\) (Sect. 38.3). Using \(x = 0\) in Eq. (38.2) predicts a mean molar weight of \[ \hat{y} = 4.398 - (0.181\times 0) = 4.398 \] for deer zero years of age (i.e., newborn male red deer). This prediction is the predicted mean molar weight; some individual deer will have molars weights greater than this, and some less than this. But in any case, this predicted mean may be nonsense: it is extrapolating beyond the data (the youngest deer in the sample is aged \(4.4\) years). Indeed, young deer are born with molars that are replaced as they grow, so the regression line does not even apply.

The value of the intercept \(b_0\) is sometimes (but not always) meaningless. The value of the slope \(b_1\) is usually of greater interest, as it explains the relationship between the two variables.

38.5.2 The meaning of \(b_1\)

The slope \(b_1\) tells us how much the value of \(y\) changes (on average) when the value of \(x\) increases by one (Sect. 38.3). For the red-deer data, \(b_1\) tells us how much the molar weight changes (on average) when age increases by one year. Specifically, each extra year older is associated with an average change of \(-0.181\)in molar weight (see Eq. (38.2)); that is, a decrease in molar weight by a mean of \(0.181\). The molars of some individual deer will lose more weight than this in some years, and some will lose less; the value is a mean weight loss per year.

To demonstrate, consider the case where \(x = 10\), and \(y\) is predicted to be \(\hat{y}= 2.588\). For deer one year older than this (i.e., \(x = 11\)) we predict \(y\) to increase by \(b_1 = -0.181\)(or, equivalently, decrease by \(0.181\)). That is, we would predict \(\hat{y}= 2.588 - 0.181 = 2.407\). This is the same prediction made by using \(x = 11\) in Eq. (38.2).

If the value of \(b_1\) is positive, then the predicted values of \(y\) increase as the values of \(x\) increase. If the value of \(b_1\) is negative, then the predicted values of \(y\) decrease as the values of \(x\) increase.

This interpretation of \(b_1\) explains the relationship: each extra year of age is associated with the weight of the molars reducing by \(0.181\), on average, in male red deer. Recall that the units of measurement of the slope here are 'grams per year'.

In general, we cannot say that the change in the value of \(x\) causes the change in the value of y unless the study is experimental (Sect. 4.4).

If the value of the slope is zero, there is no linear relationship between \(x\) and \(y\). The slope means that a change in the value of \(x\) is associated with a change of zero in the value of \(y\). In this case, the correlation coefficient is also zero.

38.6 Confidence intervals for the regression parameters

38.6.1 Introduction

The regression line is computed from the observed sample data. A regression equation exists in the population that is estimated using the sample information. That is, the regression line that is estimated from one of the countless possible samples is an estimate of the regression line in the population. In the population, the intercept is denoted by \(\beta_0\) and the slope by \(\beta_1\) (so the regression line is \(\hat{y} = \beta_0 + \beta_x\) in the population). These population values are unknown, and are estimated by the statistics \(b_0\) and \(b_1\) respectively.

The symbol \(\beta\) is the Greek letter 'beta', pronounced 'beater' (as in 'egg beater'). So \(\beta_0\) is usually pronounced as 'beater-zero', and \(\beta_1\) as 'beater-one'.

Every sample is likely to produce a slightly different value for both \(b_0\) and \(b_1\) (sampling variation), so both \(b_0\) and \(b_1\) have a standard error and a sampling distribution. The formulas for computing the values of \(b_0\) and \(b_1\) (and their standard errors) are intimidating, so we will use software to perform the calculations.

38.6.2 Describing the sampling distribution

As usual, the sample estimates can vary across all possible samples (and so have a sampling distribution). Under certain conditions (Sect. 38.8), the sampling distributions for \(b_0\) and \(b_1\) both have a normal distribution.

Usually the slope is of greater interest than the intercept, because the slope explains the relationship between the two variables (Sect. 38.5). Because of this, forming confidence intervals for \(\beta_1\) is more common than for \(\beta_0\), though the same ideas apply. For this reason, we give the sampling distribution for the slope only, but the sampling distribution for the intercept is analagous.

Definition 38.2 (Sampling distribution of a sample slope) The sampling distribution of a sample regression slope is (when certain conditions are met; Sect. 38.8) described by

- an approximate normal distribution,

- with a mean of \(\beta_1\), and

- a standard deviation, called the standard error of the slope and denoted \(\text{s.e.}(b_1)\).

(A formula exists for finding \(\text{s.e.}(b_1)\), but is tedious to use and we will not give it.)

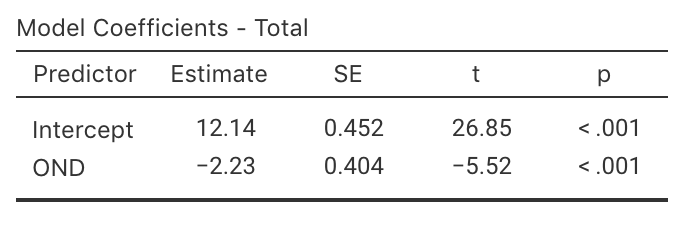

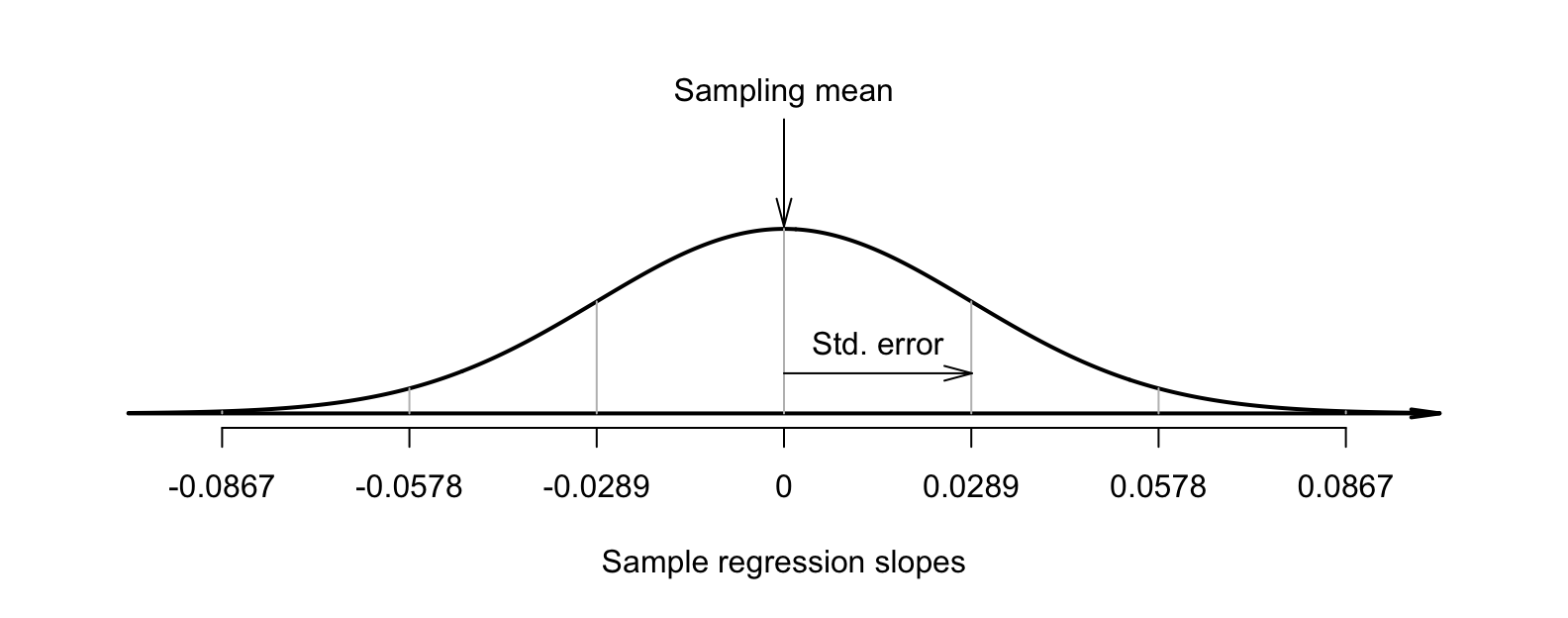

This sampling distribution describes all possible values of the sample slope from all possible samples, through sampling variation. For the red-deer data then, the values of the sample slope across all possible samples is described (Fig. 38.6) as:

- an approximate normal distribution,

- with a sampling mean whose values is \(\beta_1\), and

- with a standard deviation, called the standard error of the slope \(\text{s.e.}(b_1) = 0.029\) (from software; Fig. 38.4).

FIGURE 38.6: The distribution of sample slope for the red-deer data, around the population slope \(\beta_1\).

As seen earlier, when the sampling distribution is an approximate normal distribution, CIs have the form \[ \text{statistic} \pm ( \text{multiplier} \times \text{standard error}), \] where the multiplier is \(2\) for an approximate \(95\)% CI (from the \(68\)--\(95\)--\(99.7\) rule). Using the standard error reported by software, an approximate \(95\)% CI is \(-0.181 \pm (2\times 0.029)\), or \(-0.181 \pm 0.058\): from \(-0.239\) to \(-0.123\)/year.

Software can be used to produce exact CIs too (Fig. 38.7): \(-0.239\) to \(-0.124\)/year. The approximate and exact \(95\)% CIs are very similar. We write:

For each increase of one year in the age of male red deer, the mean molar weight increases by \(-0.181\) grams per year (approx. \(95\)% CI: \(-0.239\) to \(-0.123\); \(n = 78\)).

Alternatively (and equivalently, but probably easier to understand):

For each increase of one year in the age of male red deer, the mean molar weight decreases by \(0.181\) grams per year (approx. \(95\)% CI: \(0.239\) to \(0.123\); \(n = 78\)).

FIGURE 38.7: Output for the red-deer data, including the CIs for the regression parameters.

Example 38.6 (Cyclones) Using the software output (Fig. 38.5) for the cyclone data, \(\text{s.e.}(b_1) = 0.404\), so the approximate \(95\)% CI for the regression slope \(\beta_1\) is \[ -2.23 \pm (2 \times 0.404),\text{\qquad {or}\qquad} -2.23 \pm 0.808. \] The interval from \(-3.04\) to \(-1.42\) is likely to straddle the population slope.

38.7 Hypothesis testing for the regression parameters: \(t\)-tests

Since the regression line is computed from one of countless possible samples, any relationship between \(x\) and \(y\) observed in the sample may be due to sampling variation. Possibly, no relationship exists in the population (i.e., \(\beta_1 = 0\)); the only reason why a relationship appears in the sample is due to sampling variation. That is, a hypothesis test can be conducted for the slope. (Similar hypothesis tests can be conducted for the intercept, but are usually of less interest.)

The null hypothesis for tests about the slope is the usual 'no relationship' hypothesis. In this context, 'no relationship' means that the slope is zero (Sect. 38.5.2), so the null hypotheses (about the population) is \(H_0\): \(\beta_1 = 0\). A slope of zero is equivalent to no relationship between the variables. (We would also find \(\rho = 0\).)

For the red-deer data, the RQ posed in Sect. 37.2 is

In male red deer, does the molar weight decrease linearly as age increase?

This RQ implies these hypotheses about the slope: \[ \text{$H_0$: } \beta_1 = 0\quad\text{and}\quad\text{$H_1$: } \beta_1 < 0. \] The parameter is \(\beta_1\), the population slope for the regression equation predicting molar weight from age. The alternative hypothesis is one-tailed, based on the RQ (see Sect. 37.2).

Assuming the null hypothesis (that \(\beta_1 = 0\)) is true, the possible values of the sample slope \(b_1\) can be described. The variation in the sample slope across all possible samples when \(\beta_1 = 0\) is described (Fig. 38.8) using:

- an approximate normal distribution,

- with a sampling mean whose value is \(\beta_1 = 0\) (from \(H_0\)), and

- a standard deviation, called the standard error of the slope and denoted \(\text{s.e.}(b_1)\), with a value of \(0.0289\) (from software; Fig. 38.7).

FIGURE 38.8: The distribution of sample slopes for the red-deer data, if the population slope is \(\beta_1 = 0\).

The observed sample slope for the red-deer data is \(b_1 = -0.181\). Locating this value on Fig. 38.8 (way to the left) shows that it is very unlikely that any of the many possible samples would produce such a slope, just through sampling variation, if the population slope really was \(\beta_1 = 0\). The test statistic is found using the usual approach when the sampling distribution has an approximate normal distribution: \[\begin{align*}\index{Test statistic!t@$t$-score} t &= \frac{\text{observed value} - \text{mean of the distribution of the statistic}}{\text{standard dev. of the distribution of the statistic}}\\ &= \frac{ b_1 - \beta_1}{\text{s.e.}(b_1)} = \frac{-0.181 - 0}{0.0289} = -6.27, \end{align*}\] where the values of \(b_1\) and \(\text{s.e.}(b_1)\) are taken from the software output (Fig. 38.7). This \(t\)-score is the same value reported by the software.

To determine if the statistic is consistent with the null hypothesis, the \(P\)-value can be approximated using the \(68\)--\(95\)--\(99.7\) rule, approximated using tables, or taken from software output (Fig. 38.7). Here, the \(P\)-value will be very small; software shows the two-tailed \(P\)-value is \(P < 0.001\), so the one-tailed \(P\)-value is \(P < 0.0005\).

We write:

The sample presents very strong evidence (\(t = -6.27\); one-tailed \(P < 0.0005\)) that, in the population, the mean weight of molars decreases linearly as male red deer get older (slope: \(-0.181\); \(95\)% CI from \(-0.239\) to \(-0.124\)).

Notice the three features of writing conclusions again: an answer to the RQ; evidence to support the conclusion (\(t = -6.27\); one-tailed \(P < 0.0005\)); and some sample summary information (slope: \(-0.181\); \(95\)% CI from \(-0.239\) to \(-0.124\); \(n = 78\)).

Example 38.7 (Hypothesis testing) For the cyclone data (Example 38.5), the RQ of interest is

In the Australian region, is there a relationship between ONI and the number of cyclones?

This RQ implies these hypotheses: \[ \text{$H_0$: } \beta_1 = 0\quad\text{and}\quad\text{$H_1$: } \beta_1 \ne 0. \] From the jamovi output (Fig. 38.5), \(t = -5.52\) and the \(P\)-value is small as expected: \(P < 0.001\). We write:

The sample presents very strong evidence (\(t = -5.52\); two-tailed \(P < 0.001\)) that, in the population, the number of cyclones is related to the ONI (slope: \(-2.23\); \(95\)% CI from \(-3.04\) to \(-1.42\); \(n = 37\)).

38.8 Statistical validity conditions

The results for the CI and the hypothesis test hold when certain conditions are met. The conditions for which the test is statistically valid are the same as for correlation (Sect. 37.3):

- The relationship is approximately linear (this is necessary for the regression equation to be appropriate).

- The variation in the response variable is approximately constant for all values of the explanatory variable.

- The sample size is at least \(25\).

The sample size of \(25\) is a rough figure; some books give other values. The units of analysis are also assumed to be independent (e.g., from a simple random sample).

Other options are available if the statistical validity conditions are not met, depending on which conditions are not met. For example, generalized linear models (P. K. Dunn and Smyth 2018) may be appropriate for non-linear relationships where the variation in the response variable is not constant.

Example 38.8 (Statistical validity) For the red-deer data, the relationship is approximately linear, and the variation in molar weight appears to be somewhat constant for various ages (Fig. 16.2), so regression is appropriate. The sample size is \(n = 78\). The CI and hypothesis test are statistically valid.

Example 38.9 (Cyclones) The scatterplot for the cyclones data (Fig. 38.3) shows the relationship is approximately linear, that the variation in the number of cyclones seems reasonably constant for different values of the ONI, and the sample size is larger than \(25\) (\(n = 37\)). The CI (Example 38.6) and the test (Example 38.7) are statistically valid.

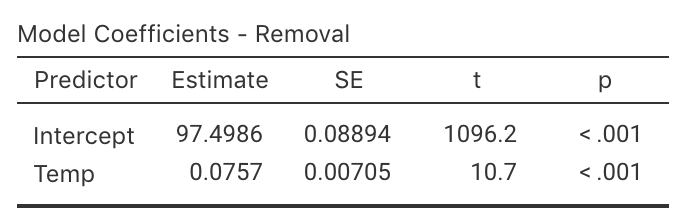

38.9 Example: removal efficiency

(This study was seen in Sect. 37.4.) In wastewater treatment facilities, air from biofiltration is passed through a membrane and dissolved in water, and is transformed into harmless by-products. The removal efficiency \(y\) (in percent) may depend on the inlet temperature (in oC; \(x\)). One RQ is

In treating biofiltration wastewater, is removal efficiency related to the inlet temperature?

The scatterplot of the data (Fig. 37.3) shows the relationship is approximately linear. From the software output (Fig. 38.9), \(b_0 = 97.5\) and \(b_1 = 0.0757\), so the regression equation is \[ \hat{y} = 97.5 + 0.0757x \] for \(x\) and \(y\) defined above. The slope quantifies the relationship, so we can test \[ \text{$H_0$: } \beta_1 = 0 \qquad\text{and}\qquad \text{$H_1$: } \beta_1 \ne 0. \] From the output, \(t = 10.7\) which is huge, and the \(P\)-value is small as expected: \(P < 0.001\). The output does not include the CI, but since \(\text{s.e.}(b_1) = 0.00705\), the approximate \(95\)% CI is \[ 0.0757 \pm (2 \times 0.00705), \quad\text{ or }\quad 0.0757 \pm 0.0141. \] We write:

Very strong evidence exists (\(t = 10.7\); \(P < 0.001\)) that inlet temperature is linearly related to removal efficiency (slope: \(0.0757\); approximate \(95\)% CI: \(0.0616\) to \(0.0898\)).

FIGURE 38.9: Regression output for the removal-efficiency data.

The CI and test are statistically valid: the relationship is approximately linear, the variation in \(y\) is approximately constant for all values of \(x\), and \(n = 32\).

38.10 Chapter summary

Regression mathematically describes the relationship between two quantitative variables. The response variable is denoted by \(y\), and the explanatory variable by \(x\). The linear relationship between \(x\) and \(y\) (the regression equation), in the sample, is \[ \hat{y} = b_0 + b_1 x, \] where \(b_0\) is a number (the intercept), \(b_1\) is a number (the slope), and the 'hat' above the \(y\) indicates that the equation gives an predicted mean value of \(y\) for the given \(x\) value. Software provides the values of \(b_0\) and \(b_1\).

The intercept is the predicted mean value of \(y\) when the value of \(x\) is zero. The slope is how much the predicted mean value of \(y\) changes, on average, when the value of \(x\) increases by \(1\).

The regression equation can be used to make predictions or to understand the relationship between the two variables. Predictions made with values of \(x\) outside the values of \(x\) used to create the regression equation (called extrapolation) may not be reliable.

The regression equation in the population is \[ \hat{y} = \beta_0 + \beta_1 x. \] To compute a confidence interval (CI) for the slope of a regression equation, software provides the standard error of \(b_1\), and the CI is \[ {b_1} \pm \left( \text{multiplier}\times\text{standard error} \right). \] The margin of error is (multiplier\({}\times{}\)standard error), where the multiplier is \(2\) for an approximate \(95\)% CI (using the \(68\)--\(95\)--\(99.7\) rule).

To test a hypothesis about a population correlation coefficient \(\rho\):

- Write the null hypothesis (\(H_0\)) and the alternative hypothesis (\(H_1\)).

- Initially assume the value of \(\beta_1\) in the null hypothesis to be true.

- Then, describe the sampling distribution, which describes what to expect from the sample correlation coefficient on this assumption: under certain statistical validity conditions, the sample correlation coefficients vary with:

- an approximate normal distribution,

- with sampling mean whose value is the value of \(\beta_1 = 0\) (from \(H_0\)), and

- having a standard deviation of \(\displaystyle \text{s.e.}(b_1)\).

- Compute the value of the test statistic: \[ t = \frac{b_1 - \beta_1}{\text{s.e.}(b_1)}, \] where \(r\) is sample correlation coefficients.

- The \(t\)-value is like a \(z\)-score, and so an approximate \(P\)-value can be estimated using the \(68\)--\(95\)--\(99.7\) rule, or found using software.

- Make a decision, and write a conclusion.

- Check the statistical validity conditions.

38.11 Quick review questions

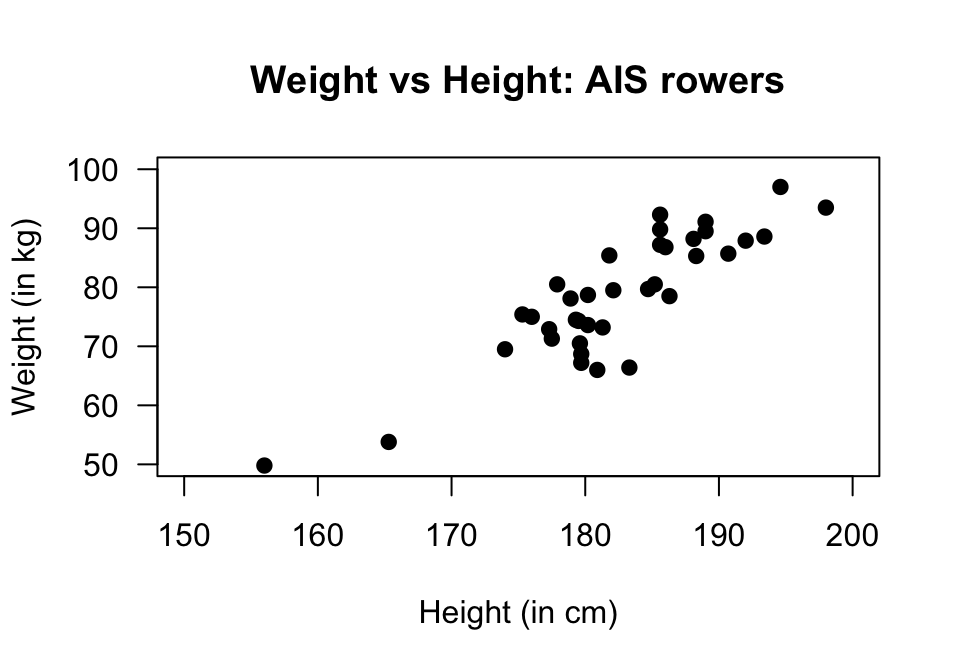

Telford and Cunningham (1991) examined the relationship between the height and weight of \(n = 37\) rowers at the Australian Institute of Sport (AIS; Fig. 38.10).

FIGURE 38.10: Scatterplot of weight against height of rowers at the AIS.

- What is the \(y\)-variable?

- Using the 'rise-over-run' idea, what is the approximate value of the slope?

- The regression equation is \(\hat{y} = -138 + 1.2 x\).

What does \(x\) represent?

- What does the 'hat' above the \(y\) mean?

- What weight is predicted for a rower who is \(180\)tall?

- The standard error of the slope is \(0.112\). What is the value of the test statistic (to two decimal places) to test if the population slope is zero?

- True or false: The \(P\)-value for this test will be very small.

- True or false: The units of the slope are kg/cm.

- True or false: Making a prediction for the weight of a rower weighing \(220\)would be an example of extrapolation.

38.12 Exercises

Answers to odd-numbered exercises are available in App. E.

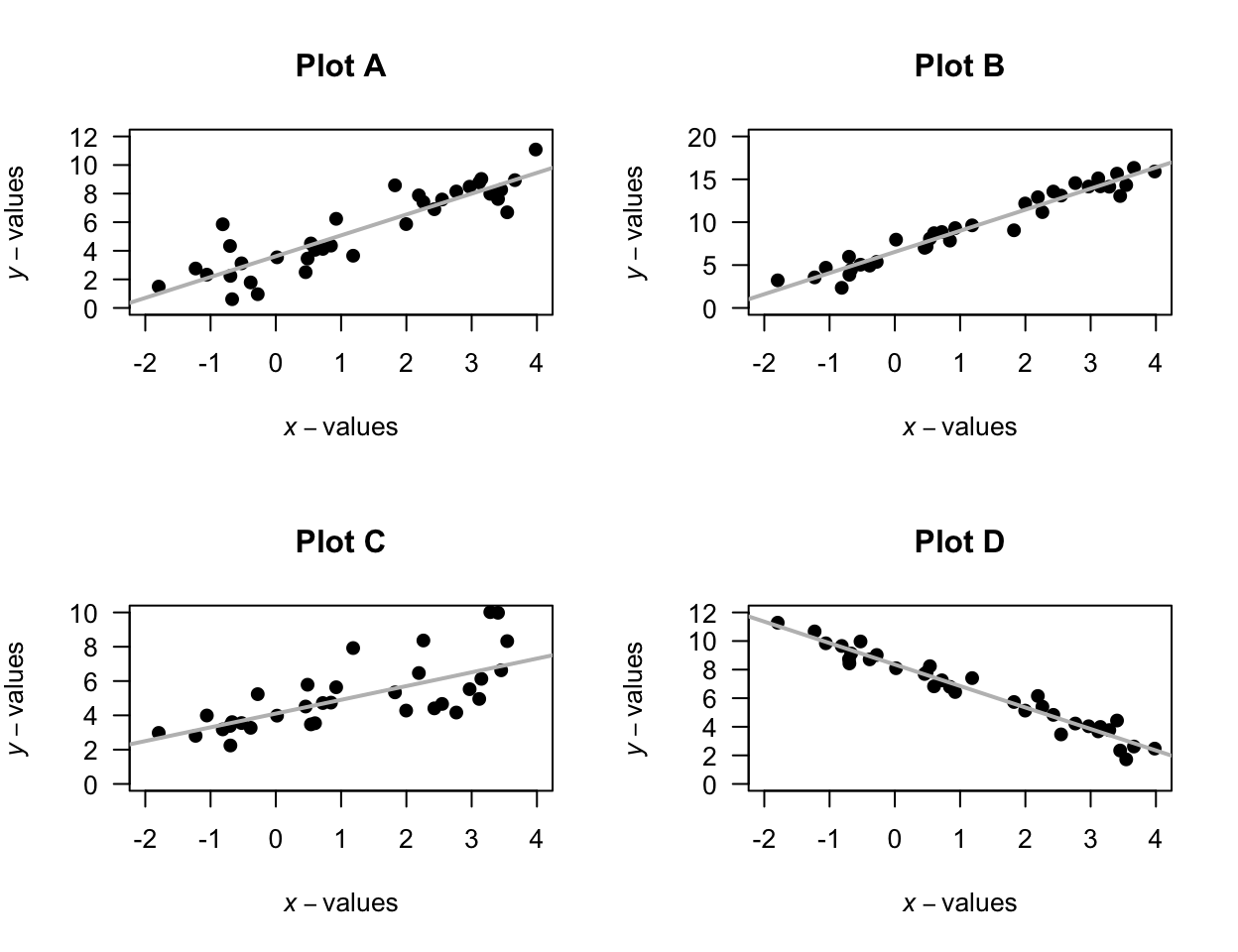

Exercise 38.1 For each of the plots in Fig. 38.11, where appropriate:

- estimate the value of \(r\) (this is hard!).

- estimate the intercept of the regression line.

- estimate the slope of the regression line using the rise-over-run idea.

- write down the estimated regression equation.

FIGURE 38.11: Four scatterplots.

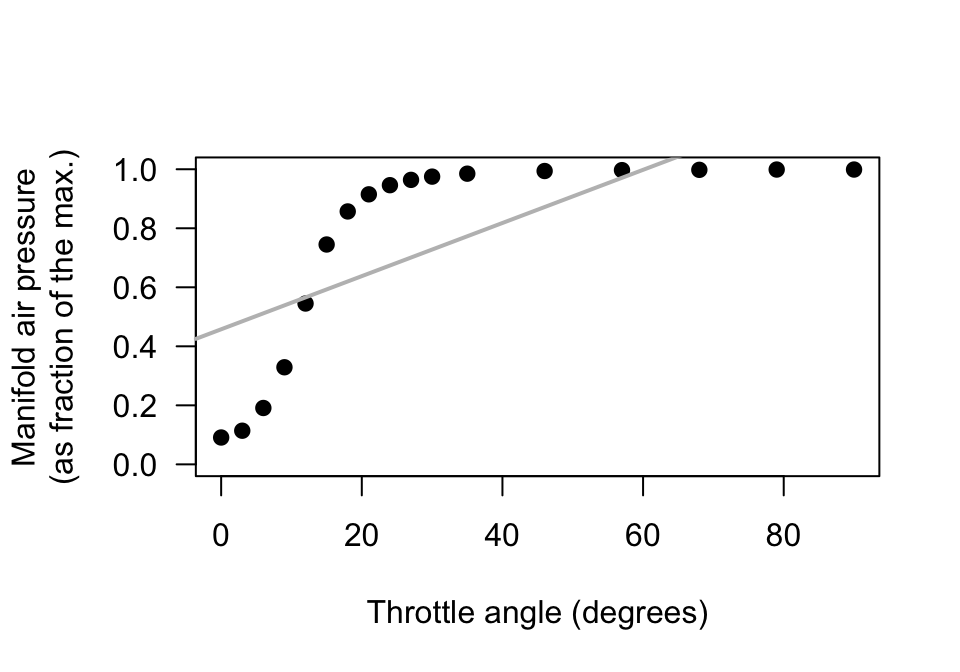

Exercise 38.2 [Dataset: Throttle]

Amin and Mahmood-ul-Hasan (2019) measured the throttle angle (\(x\)) and the manifold air pressure (\(y\)), as a fraction of the maximum value, in gas engines.

- The value of \(r\) is given in the paper as \(0.972986604\). Comment on this value, and what it means.

- Comment on the use of a regression model, based on the scatterplot (Fig. 38.12).

- The authors fitted the following regression model: \(y = 0.009 + 0.458x\). Identify errors that the researchers have made when giving this regression equation (there are many).

- Critique the researchers' approach.

FIGURE 38.12: Manifold air pressure plotted against throttle angle for an internal-combustion gas engine.

Exercise 38.3 For each regression equation below, identify the values of \(b_0\) and \(b_1\).

- \(\hat{y} = 3.5 - 0.14x\).

- \(\hat{y} = -0.0047x + 2.1\).

Exercise 38.4 For each regression equation below, identify the values of \(b_0\) and \(b_1\).

- \(\hat{y} = -1.03 + 7.2x\).

- \(\hat{y} = -1.88x - 0.46\).

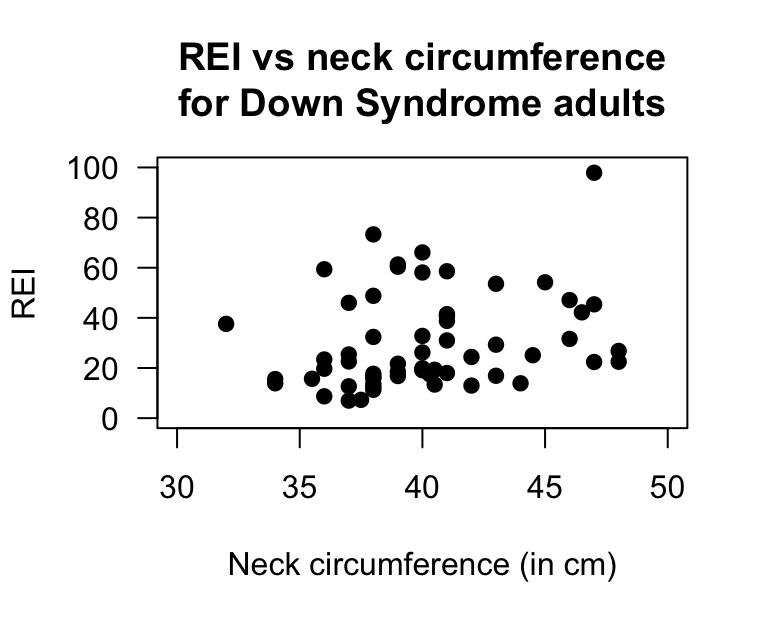

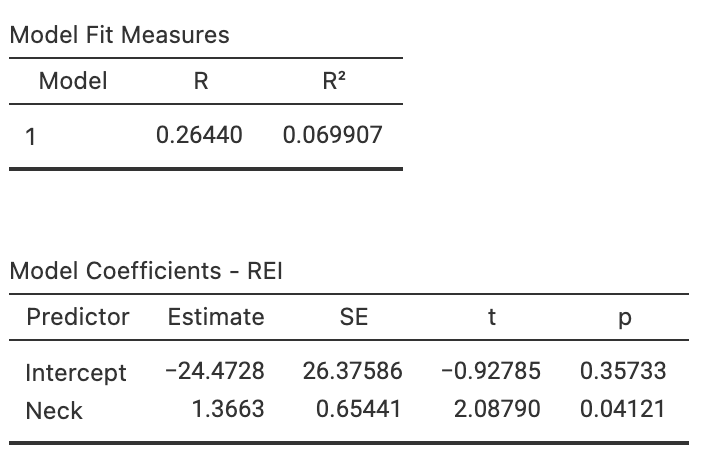

Exercise 38.5 [Dataset: OSA]

de Carvalho et al. (2020) studied obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA) in adults with Down Syndrome.

Sixty adults underwent a sleep study and had various information recorded.

The response variable is OSA severity: the average number of episodes of sleep disruption (according to specific criteria) per hour of sleep (called the Respiratory Event Index, REI).

One research question is:

Among Down Syndrome adults, is there a linear relationship between the REI and neck size?

Here, \(x\) is the neck size (in cm), and \(y\) is the REI value. The data are shown in Fig. 38.14.

- Using the software output (Fig. 38.13, right panel), determine the value of the correlation coefficient.

- Compute the value of \(R^2\), and interpret what this means.

- Using the software output, write down the values of the intercept and the slope, and hence the regression equation.

- Interpret what the slope in the regression equation means.

- Find a CI for the slope.

- Perform a hypothesis to test if a relationship exists between the variables.

- Are the test and CI statistically valid?

FIGURE 38.13: Left: Scatterplot of the neck circumference vs REI for Down Syndrome adults. Right: software output.

FIGURE 38.14: The obstructive sleep apnoea dataset.

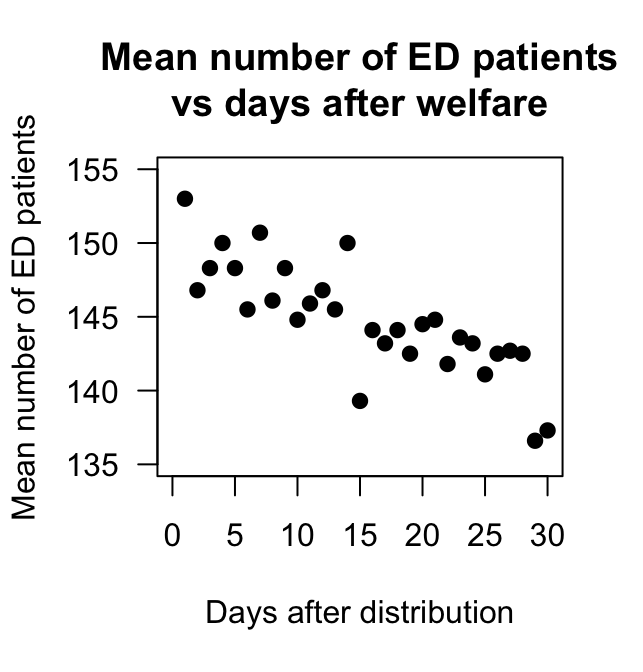

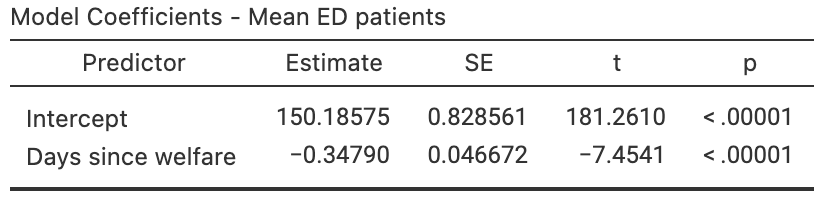

Exercise 38.6 [Dataset: EDpatients]

Brunette, Kominsky, and Ruiz (1991) studied the relationship between the number of emergency department (ED) patients and the number of days following the distribution of monthly welfare monies, from 1986 to 1988 in Minneapolis, MN.

The data (extracted from Brunette, Kominsky, and Ruiz (1991)) and the software output are displayed in Fig. 38.15.

- Write down the estimated regression equation.

- Interpret the slope in the regression equation.

- Find a \(95\)% CI for the slope.

- Conduct a hypothesis test for the slope, and explain what the results mean.

FIGURE 38.15: The number of emergency department patients, and the number of days since distribution of welfare. Left: scatterplot. Right: software output.

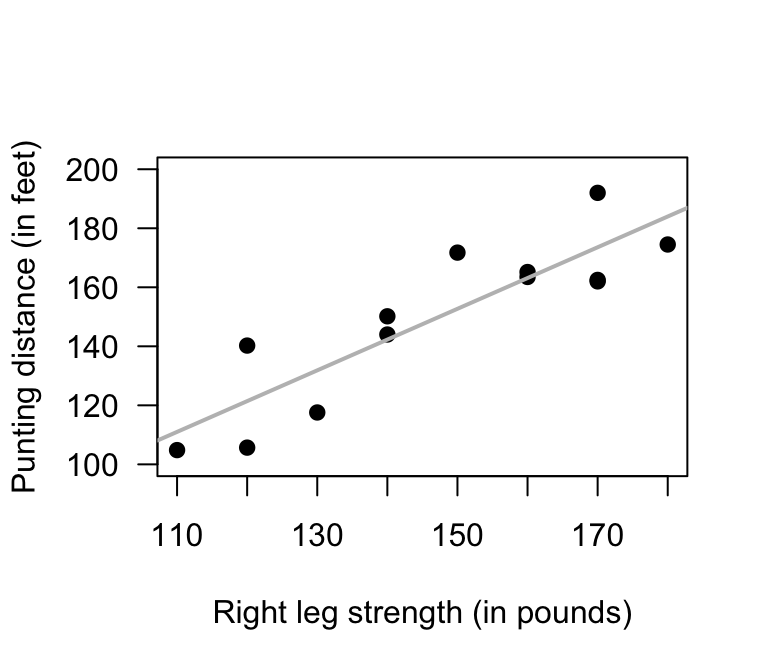

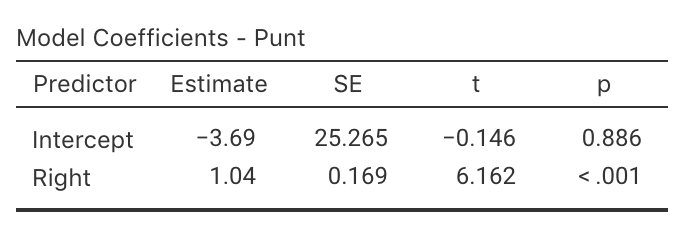

Exercise 38.7 [Dataset: Punting]

(These data were also seen in Exercise 37.7.)

Myers (1990) (p. 75) measured the right-leg strengths \(x\) of \(13\) American footballer players (using a weight lifting test), and the distance \(y\) they punt a football (with their right leg).

- Use the scatterplot (Fig. 38.16) to approximate of the values of the intercept and slope.

- Using the software output (Fig. 38.16), write down the value of the slope (\(b_1\)) and \(y\)-intercept (\(b_0\)).

- Hence write down the regression equation.

- Interpret the slope (\(b_1\)).

- Write the hypotheses for testing for a relationship in the population

- Write down the \(t\)-score and \(P\)-value from the output.

- Determine an approximate \(95\)% CI for the population slope \(\beta_1\).

- Write a conclusion.

FIGURE 38.16: Punting distance and right leg strength. Left: scatterplot. Right: software output.

Exercise 38.8 [Dataset: Gorillas]

(These data were also seen in Exercise 16.9.)

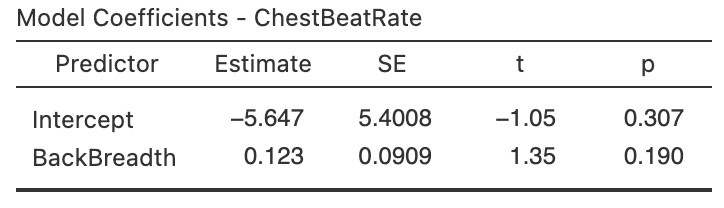

Wright et al. (2021) examined \(25\) gorillas and recorded information about their chest beating and their size (measured by the breadth of the gorillas' backs).

The relationship is shown in a scatterplot in Fig. 16.14 (left panel).

Use the software output (Fig. 38.17) to find the regression line, and perform a hypothesis tests for the slope. Write a conclusion.

FIGURE 38.17: Software regression output for the gorilla data.

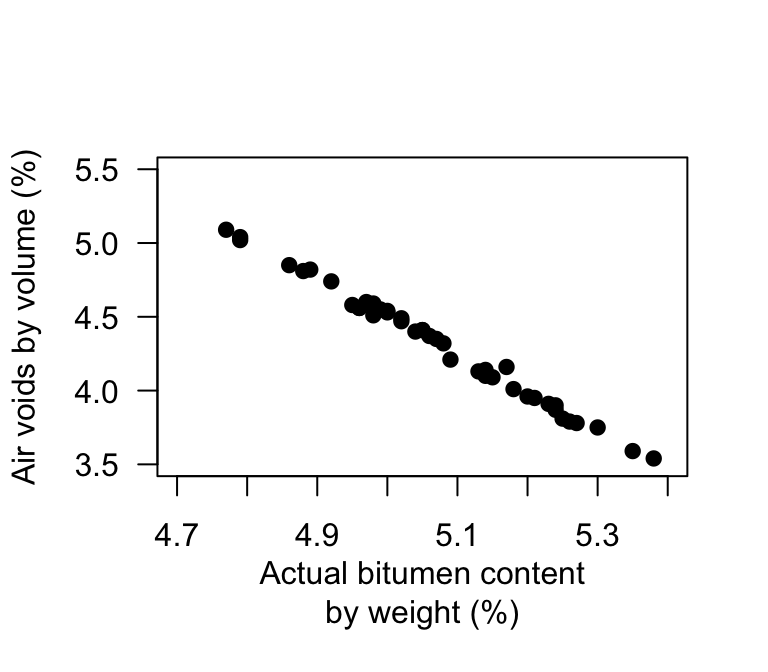

Exercise 38.9 [Dataset: Bitumen]

(These data were also seen in Exercise 37.6.)

Panda, Das, and Sahoo (2018) made \(n = 42\) observations of studied hot mix asphalt, and measured the volume of air voids and the bitumen content by weight (Fig. 38.18).

Use the software output (Fig. 38.18) to answer these questions.

- Write down the regression equation.

- Interpret what the regression equation means.

- Perform a test to determine is there is a relationship between the variables.

- Predict the mean percentage of air voids by volume when the percentage bitumen is \(5.0\)%. Do you expect this to be a good prediction? Why or why not?

- Predict the mean percentage of air voids by volume when the percentage bitumen is \(6.0\)%. Do you expect this to be a good prediction? Why or why not?

FIGURE 38.18: Air voids in bitumen samples.

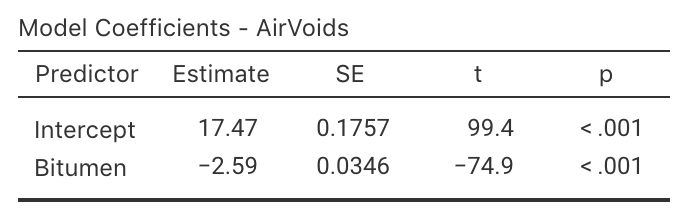

Exercise 38.10 [Dataset: Possums]

J. L. Williams et al. (2022) studied Leadbeater's possums in the Victorian Central Highlands.

They recorded, among other information, the body weight of the possums and their location, including the elevation of the location.

A scatterplot of the data is shown in Fig. 37.9.

The software output for fitting the regression line is shown in Fig. 38.19.

- Write down the regression equation.

- Interpret what the regression equation means.

- Perform a test to determine is there is a relationship between the possum weight and the elevation.

- Interpret the meaning of the slope.

- Predict the mean weight of male possums at an elevation of \(1000\). Do you expect this to be a good prediction? Why or why not?

- Predict the mean weight of male possums at an elevation of \(200\). Do you expect this to be a good prediction? Why or why not?

FIGURE 38.19: The relationship between weight of possums and the elevation of their location.

Exercise 38.11 [Dataset: Soils]

(These data were also seen in Exercise 37.8.)

The California Bearing Ratio (CBR) value is used to describe soil sub-grade for flexible pavements (such as in the design of air field runways).

Talukdar (2014) examined the relationship between CBR and other properties of soil, including the plasticity index (PI, a measure of the plasticity of the soil).

The scatterplot from \(16\) different soil samples from Assam, India, is shown in Fig. 37.8.

Estimate the regression equation, using the 'rise-over-run' idea.

Exercise 38.12 A study of \(n = 31\) people on the use of sunscreen (Heerfordt et al. 2018) explored the relationship between the time (in minutes) spent on sunscreen application \(x\) and the amount (in grams) of sunscreen applied \(y\). The fitted regression equation was \(\hat{y} = 0.27 + 2.21x\).

- Interpret the meaning of \(b_0\) and \(b_1\). Do they seems sensible?

- According to the article, a hypothesis for testing \(\beta_0\) produced a \(P\)-value much larger than \(0.05\). What does this mean?

- If someone spent \(84\)applying sunscreen, how much sunscreen would you predict that they used?

- The article reports that \(R^2 = 0.64\). Interpret this value.

- What is the value of the correlation coefficient?

Exercise 38.13 Bhargava et al. (1985) stated (p. 1617):

In developing countries [...] logistic problems prevent the weighing of every newborn child. A study was performed to see whether other simpler measurements could be substituted for weight to identify neonates of low birth weight and those at risk.

One relationship they studied was between infant chest circumference (in cm) \(x\) and birth weight (in grams) \(y\) was given as: \[ \hat{y} = -3440.2403 + 199.2987x. \] The correlation coefficient was \(r = 0.8696\) with \(P < 0.001\).

- Critique the way in which the regression equation and correlation coefficient are reported.

- Based on the regression equation only, could chest circumference be used as a useful predictor of birth weight? Explain.

- Based on the correlation information only, could chest circumference be used as a useful predictor of birth weight? Explain.

- Interpret the intercept and the slope of the regression equation.

- What units of measurement are the intercept and slope measured in?

- Predict the birth weight of an infant with a chest circumference of 30cm.

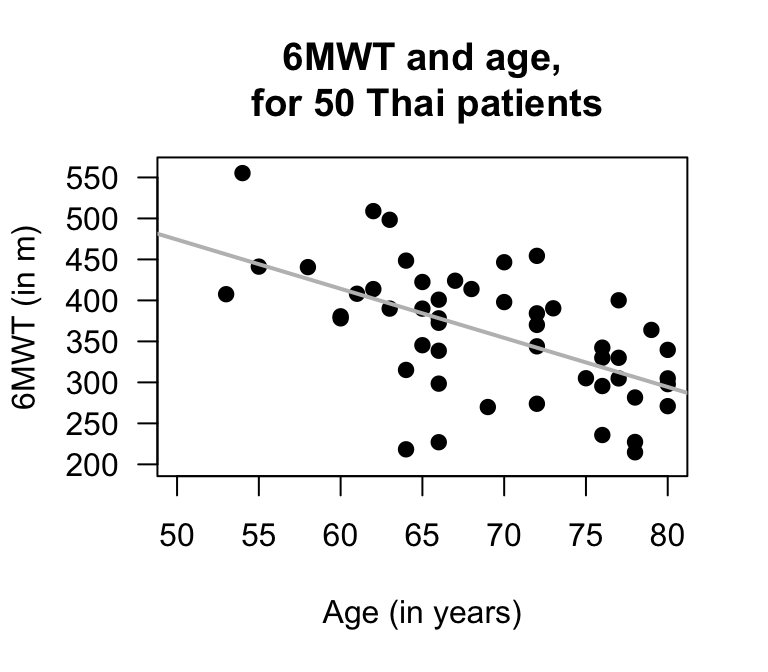

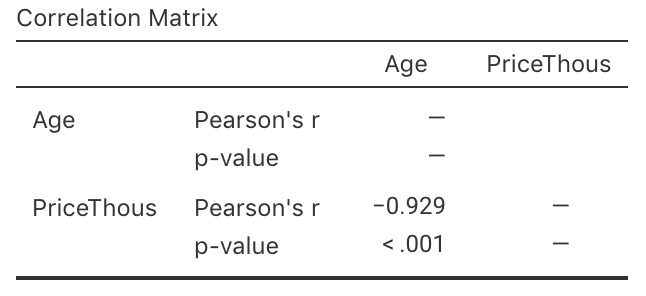

Exercise 38.14 [Dataset: SixMWT]

The Six-Minute Walk Test (6MWT) measures how far subjects can walk in six minutes, and is used as a simple, low-cost evaluation of fitness and other health-related measures.

Saiphoklang, Pugongchai, and Leelasittikul (2022) measured the 6MWT distance and the age of subjects:

For Thai patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, is there a linear relationship between the 6MWT and age?

The data collected to answer this RQ are shown below. The data are plotted in Fig. 38.20 (left panel), and software output shown in Fig. 38.20 (right panel).

- What is the value of the correlation coefficient? Explain.

- Use the output to write down the regression equation.

- Interpret the meaning of the intercept and slope. Are these both sensible? Explain.

- Conduct a test to determine if a relationship exists between the 6MWT and age in the population.

- Construct an approximate \(95\)% for the slope.

- Are the test and CI statistically valid?

- What is the predicted 6MWT distance for a patient who is \(60\) years old?

FIGURE 38.20: Left: the 6MWT plotted against age. The solid grey line is the regression line. Right: software output.

Exercise 38.15 Draw the regression line corresponding to \(\hat{y} = 5 + 2x\) for values of \(x\) between \(0\) and \(10\).

- Add some points to the scatterplot such that the correlation is approximately \(r = 0.9\).

- Add some more points to the scatterplot such that the correlation is approximately \(r = 0.3\).

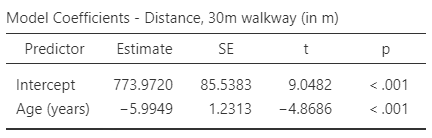

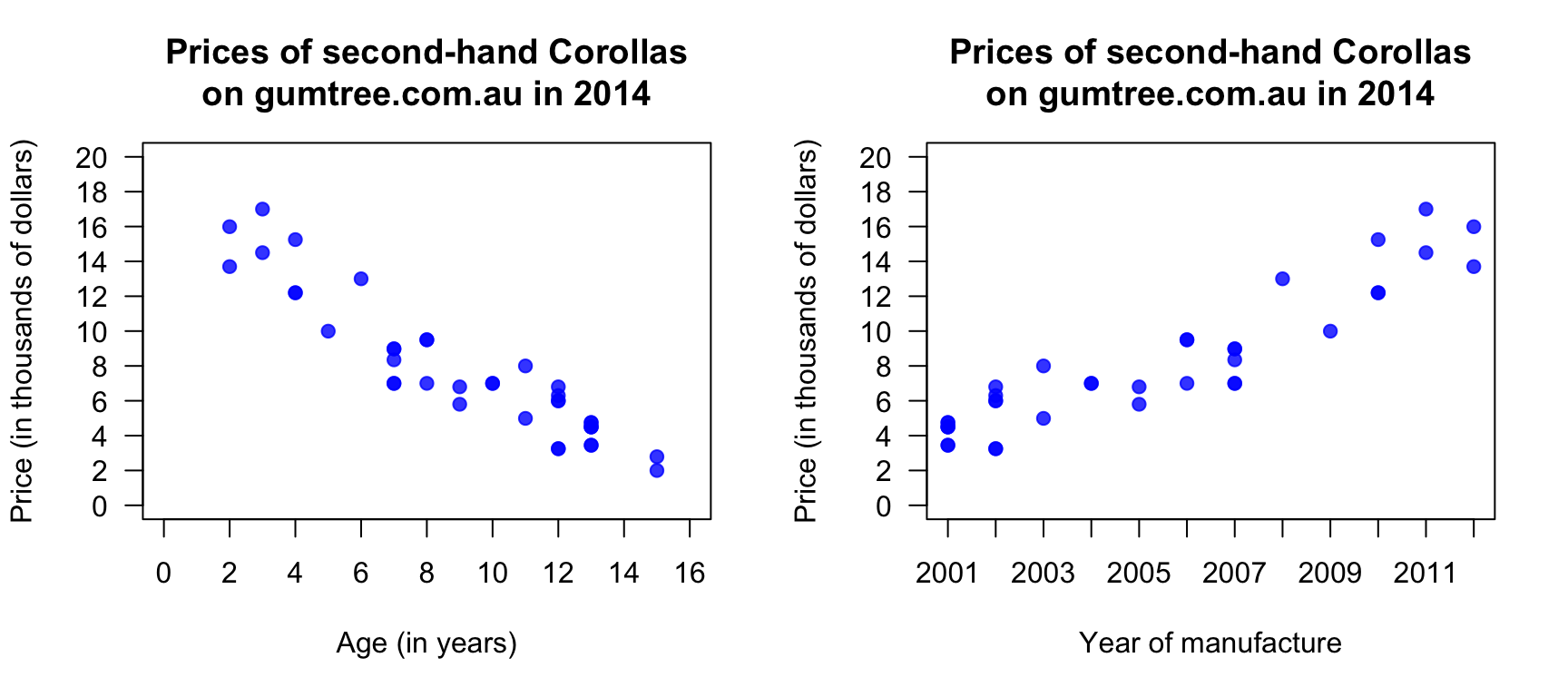

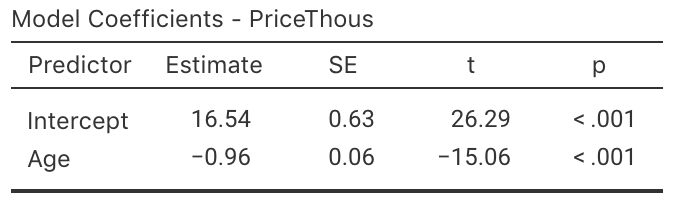

Exercise 38.16 [Dataset: Corollas]

I was wondering about how the age of second-hand cars impact their price.

On 25 June, 2014, I searched

Gum Tree

(an Australian online market place), for Toyota Corolla in the 'Cars, Vans & Utes' category.

The age and the price of each (second-hand) car was recorded from the first two pages of results that were returned.

I then restricted the data to cars \(15\) years old or younger (and removed one \(13\)-year-old Corolla advertised for sale for $\(390\,000\), assuming this was an error). I then produced the scatterplot in Fig. 38.21 (left panel).

FIGURE 38.21: The price of second-hand Toyota Corollas (\(n = 38\)) as advertised on Gum Tree on 25 June 2014, plotted against age (left) and year of manufacture (right).

- Describe the relationship displayed in the graph in words.

- What else could influence the price of a second-hand Corollas?

- From the scatterplot, draw (if you can) or estimate by eye an approximation of the regression line.

- On the scatterplot, locate a seven-year-old Corolla selling for $\(15\,000\). Would this be cheap or expensive?

- As stated, I removed one observation: a 13-year-old Corolla for sale at $\(390\,000\). What do you think the price was meant to be listed as, by looking at the scatterplot? Explain.

- Estimate the value of \(b_0\) (the intercept) from the line you drew. What does this mean? Do you think this value is meaningful?

- Estimate the value of \(b_1\) (the slope) from the line you drew. What does this mean? Do you think this value is meaningful?

- From the line you drew above, write down an estimate of the regression equation.

- Use the software output (Fig. 38.22) relating the price (in thousands of dollars) to age to write down the regression equation.

- Using the software output, write down the value of \(r\). Using this value of \(r\), compute the value of \(R^2\). What does this mean?

FIGURE 38.22: The jamovi output, analysing the Corolla data

Use the regression equation from the software output to estimate the sale price of a Corolla that is \(20\)-years-old, and explain your answer.

Would a Corolla \(6\)-years-old advertised for sale at $\(15\,000\) appear to be good value? Estimate the sale price and explain your answer.

Using the software output, perform a suitable hypothesis test to determine if there is evidence that lower prices are associated with older Corollas.

Compute an approximate \(95\)% confidence interval for the population slope (use the software output in Fig. 38.22.

-

I could have drawn a scatterplot with Price on the vertical (up-and-down) axis and Year of manufacture on the horizontal (left-to-right) axis (Fig. 38.21, right panel). For this graph:

- What is the value of the correlation coefficient?

- How would the value of \(R^2\) change?

- How would the value of the slope change?

- How would the value of the intercept change?