26 Difference-in-differences

Examples in marketing

- (Liaukonyte, Teixeira, and Wilbur 2015): TV ad on online shopping

- (Yanwen Wang, Lewis, and Schweidel 2018): political ad source and message tone on vote shares and turnout using discontinuities in the level of political ads at the borders

- (Datta, Knox, and Bronnenberg 2018): streaming service on total music consumption using timing of users adoption of a music streaming service

- (Janakiraman, Lim, and Rishika 2018): data breach announcement affect customer spending using timing of data breach and variation whether customer info was breached in that event

- (Israeli 2018): digital monitoring and enforcement on violations using enforcement of min ad price policies

- (Ramani and Srinivasan 2019): firms respond to foreign direct investment liberalization using India’s reform in 1991.

- (Pattabhiramaiah, Sriram, and Manchanda 2019): paywall affects readership

- (Akca and Rao 2020): aggregators for airlines business effect

- (Lim et al. 2020): nutritional labels on nutritional quality for other brands in a category using variation in timing of adoption of nutritional labels across categories

- (Guo, Sriram, and Manchanda 2020): payment disclosure laws effect on physician prescription behavior using Timing of the Massachusetts open payment law as the exogenous shock

- (S. He, Hollenbeck, and Proserpio 2022): using Amazon policy change to examine the causal impact of fake reviews on sales, average ratings.

- (Peukert et al. 2022): using European General data protection Regulation, examine the impact of policy change on website usage.

Examples in econ:

(Fuchs-Schündeln and Hassan 2016): macro

Show the mechanism via

Mediation Under DiD analysis: see (Habel, Alavi, and Linsenmayer 2021)

Moderation analysis: see (Goldfarb and Tucker 2011)

Steps to trust DID:

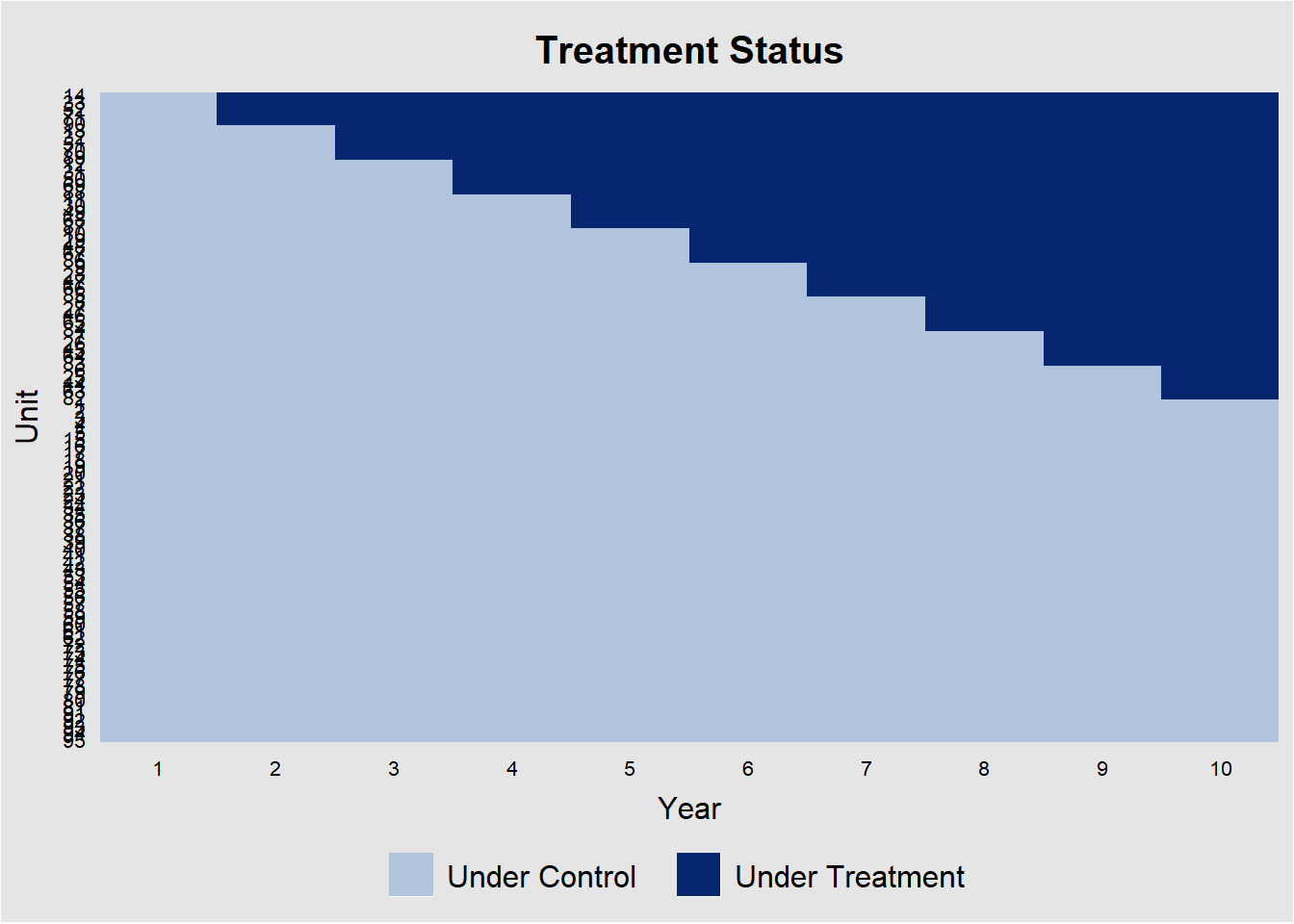

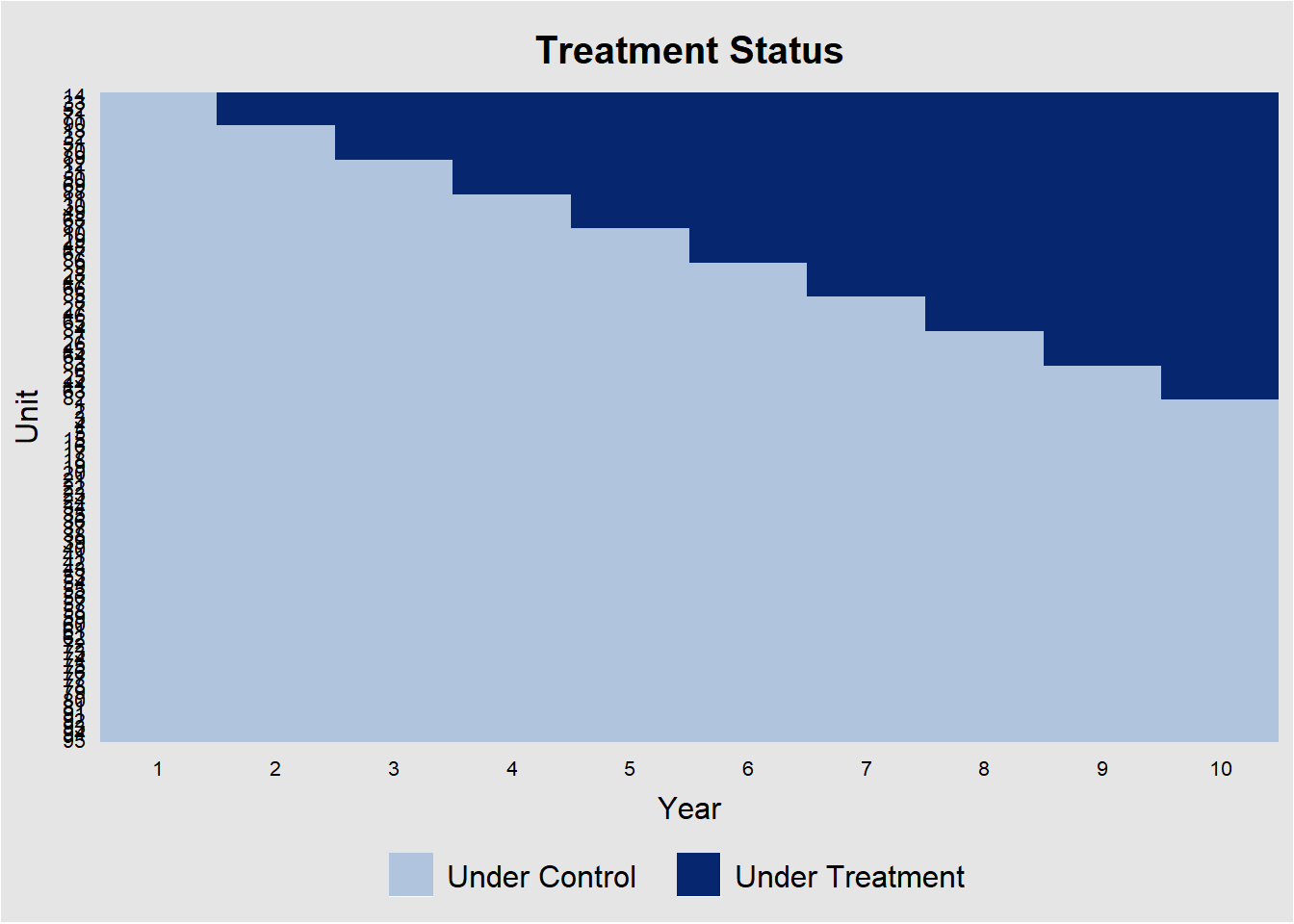

Visualize the treatment rollout (e.g.,

panelView).Document the number of treated units in each cohort (e.g., control and treated).

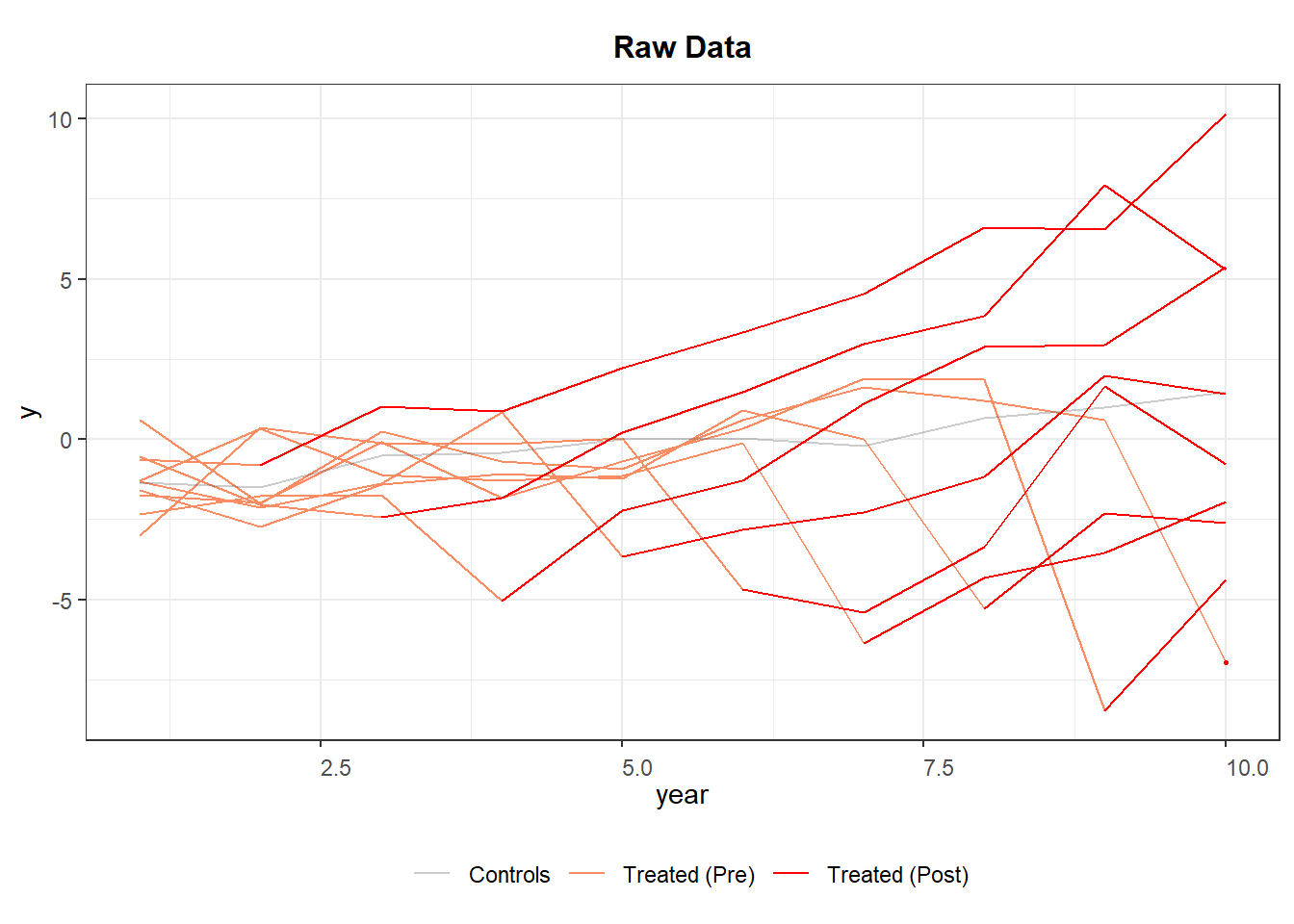

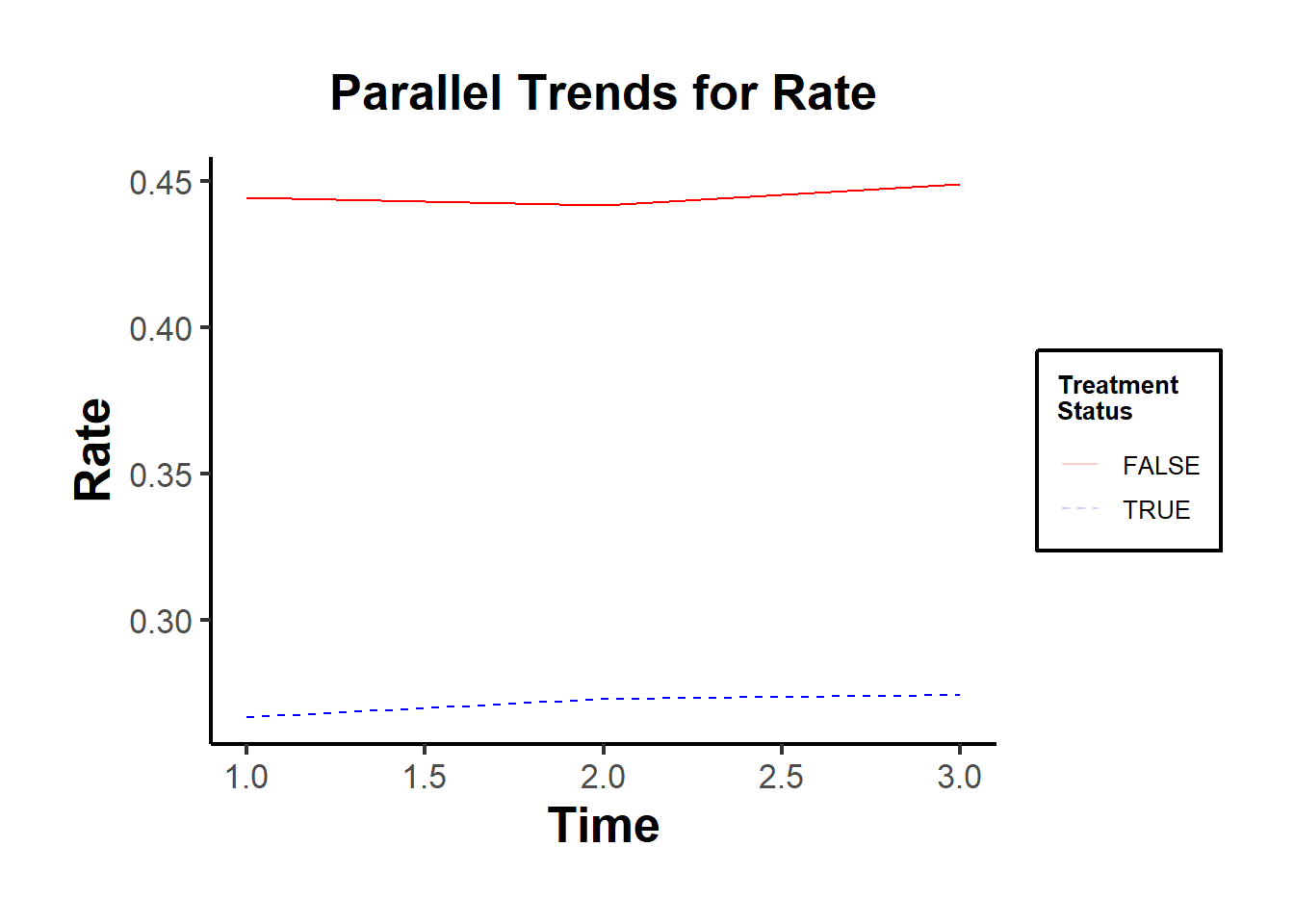

Visualize the trajectory of average outcomes across cohorts (if you have multiple periods).

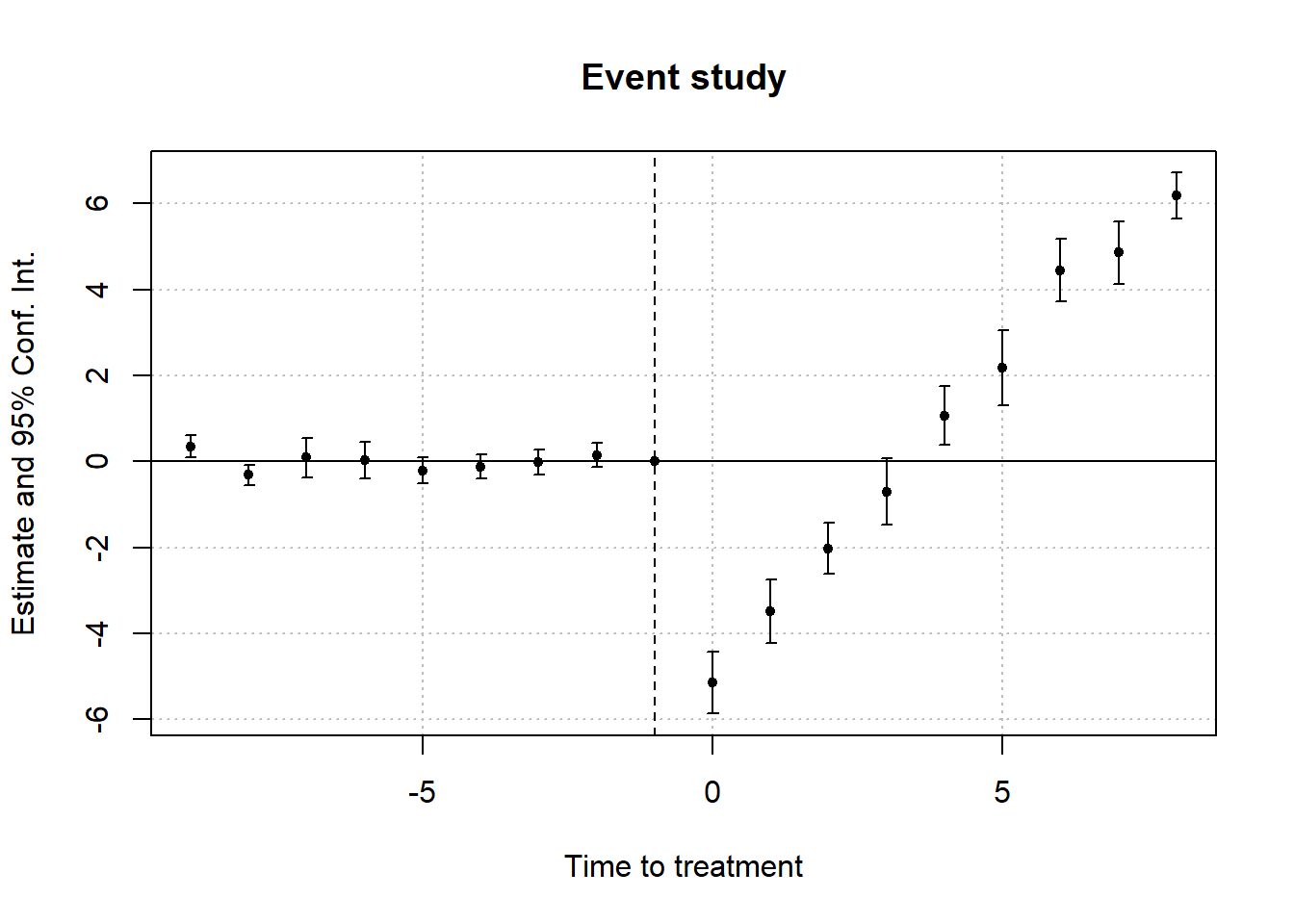

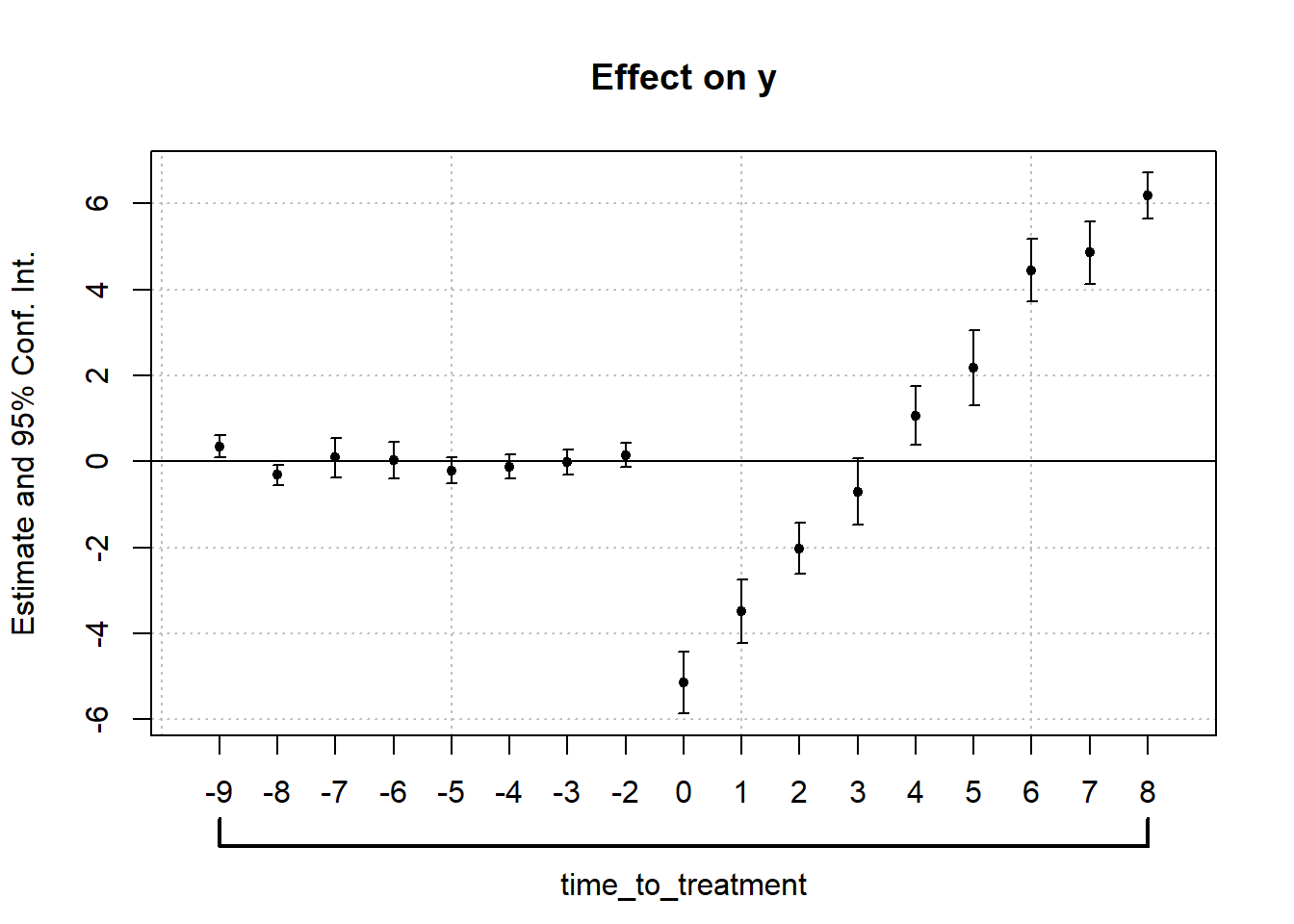

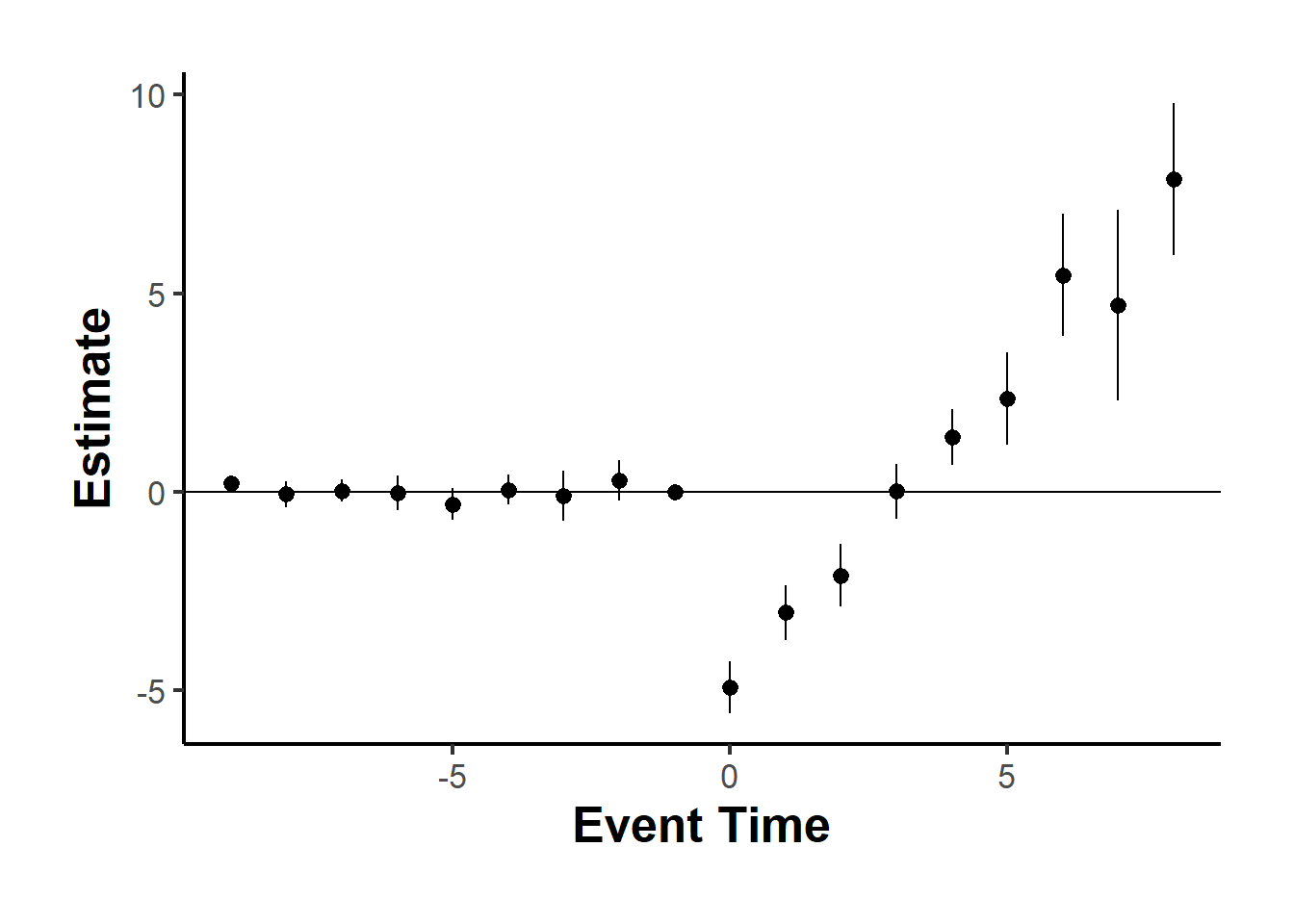

Parallel Trends Conduct an event-study analysis with and without covariates.

For the case with covariates, check for overlap in covariates between treated and control groups to ensure control group validity (e.g., if the control is relatively small than the treated group, you might not have overlap, and you have to make extrapolation).

Conduct sensitivity analysis for parallel trend violations (e.g.,

honestDiD).

26.1 Visualization

library(panelView)

library(fixest)

library(tidyverse)

base_stagg <- fixest::base_stagg |>

# treatment status

dplyr::mutate(treat_stat = dplyr::if_else(time_to_treatment < 0, 0, 1)) |>

select(id, year, treat_stat, y)

head(base_stagg)

#> id year treat_stat y

#> 2 90 1 0 0.01722971

#> 3 89 1 0 -4.58084528

#> 4 88 1 0 2.73817174

#> 5 87 1 0 -0.65103066

#> 6 86 1 0 -5.33381664

#> 7 85 1 0 0.49562631

panelView::panelview(

y ~ treat_stat,

data = base_stagg,

index = c("id", "year"),

xlab = "Year",

ylab = "Unit",

display.all = F,

gridOff = T,

by.timing = T

)

# alternatively specification

panelView::panelview(

Y = "y",

D = "treat_stat",

data = base_stagg,

index = c("id", "year"),

xlab = "Year",

ylab = "Unit",

display.all = F,

gridOff = T,

by.timing = T

)

# Average outcomes for each cohort

panelView::panelview(

data = base_stagg,

Y = "y",

D = "treat_stat",

index = c("id", "year"),

by.timing = T,

display.all = F,

type = "outcome",

by.cohort = T

)

#> Number of unique treatment histories: 10

26.2 Simple Dif-n-dif

A tool developed intuitively to study “natural experiment”, but its uses are much broader.

Fixed Effects Estimator is the foundation for DID

-

Why is dif-in-dif attractive? Identification strategy: Inter-temporal variation between groups

Cross-sectional estimator helps avoid omitted (unobserved) common trends

Time-series estimator helps overcome omitted (unobserved) cross-sectional differences

Consider

\(D_i = 1\) treatment group

\(D_i = 0\) control group

\(T= 1\) After the treatment

\(T =0\) Before the treatment

| After (T = 1) | Before (T = 0) | |

|---|---|---|

| Treated \(D_i =1\) | \(E[Y_{1i}(1)|D_i = 1]\) | \(E[Y_{0i}(0)|D)i=1]\) |

| Control \(D_i = 0\) | \(E[Y_{0i}(1) |D_i =0]\) | \(E[Y_{0i}(0)|D_i=0]\) |

missing \(E[Y_{0i}(1)|D=1]\)

The Average Treatment Effect on Treated (ATT)

\[ \begin{aligned} E[Y_1(1) - Y_0(1)|D=1] &= \{E[Y(1)|D=1] - E[Y(1)|D=0] \} \\ &- \{E[Y(0)|D=1] - E[Y(0)|D=0] \} \end{aligned} \]

More elaboration:

- For the treatment group, we isolate the difference between being treated and not being treated. If the untreated group would have been affected in a different way, the DiD design and estimate would tell us nothing.

- Alternatively, because we can’t observe treatment variation in the control group, we can’t say anything about the treatment effect on this group.

Extension

- More than 2 groups (multiple treatments and multiple controls), and more than 2 period (pre and post)

\[ Y_{igt} = \alpha_g + \gamma_t + \beta I_{gt} + \delta X_{igt} + \epsilon_{igt} \]

where

\(\alpha_g\) is the group-specific fixed effect

\(\gamma_t\) = time specific fixed effect

\(\beta\) = dif-in-dif effect

\(I_{gt}\) = interaction terms (n treatment indicators x n post-treatment dummies) (capture effect heterogeneity over time)

This specification is the “two-way fixed effects DiD” - TWFE (i.e., 2 sets of fixed effects: group + time).

- However, if you have Staggered Dif-n-dif (i.e., treatment is applied at different times to different groups). TWFE is really bad.

- Long-term Effects

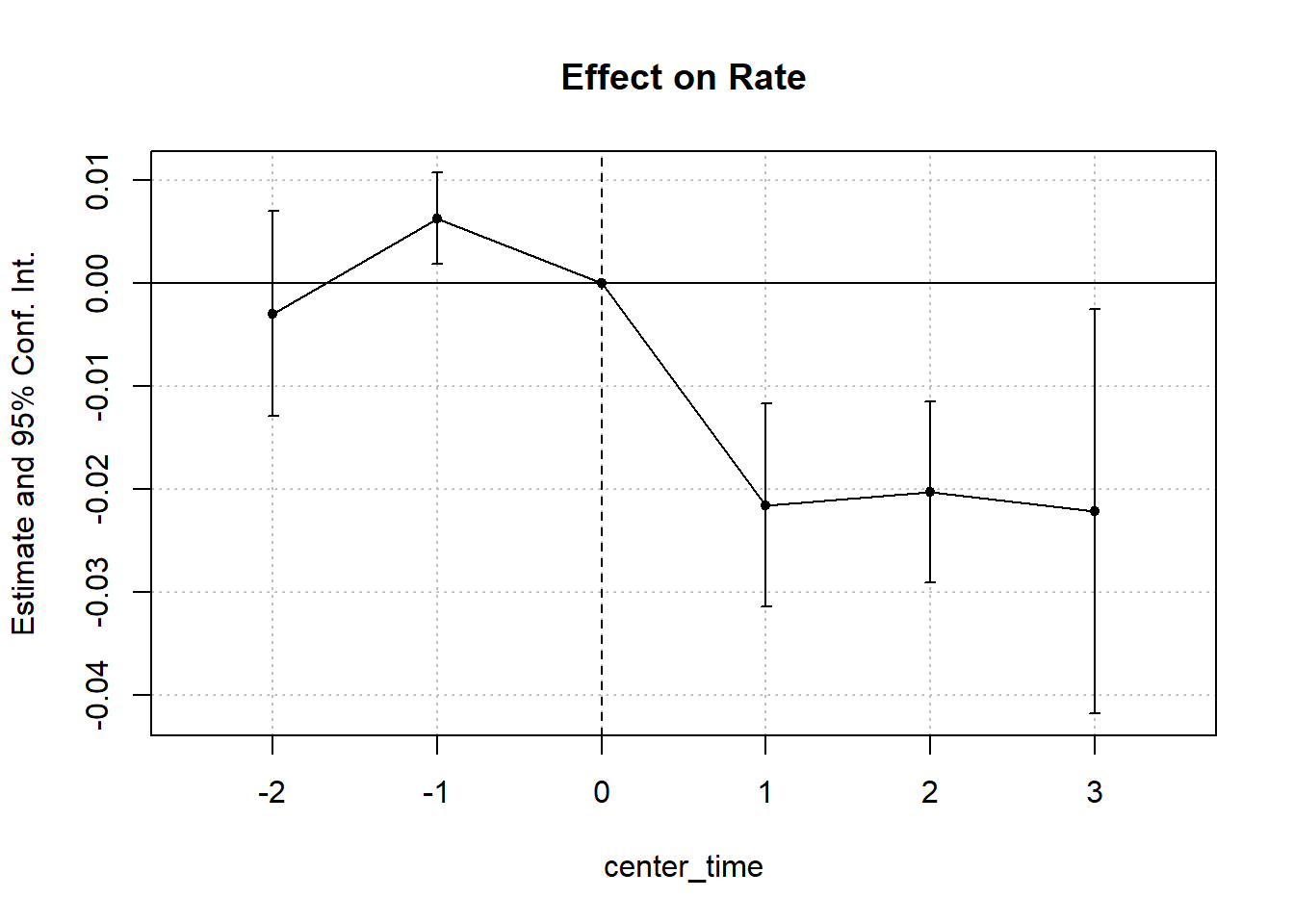

To examine the dynamic treatment effects (that are not under rollout/staggered design), we can create a centered time variable,

| Centered Time Variable | Period |

|---|---|

| … | |

| \(t = -1\) | 2 periods before treatment period |

| \(t = 0\) |

Last period right before treatment period Remember to use this period as reference group |

| \(t = 1\) | Treatment period |

| … |

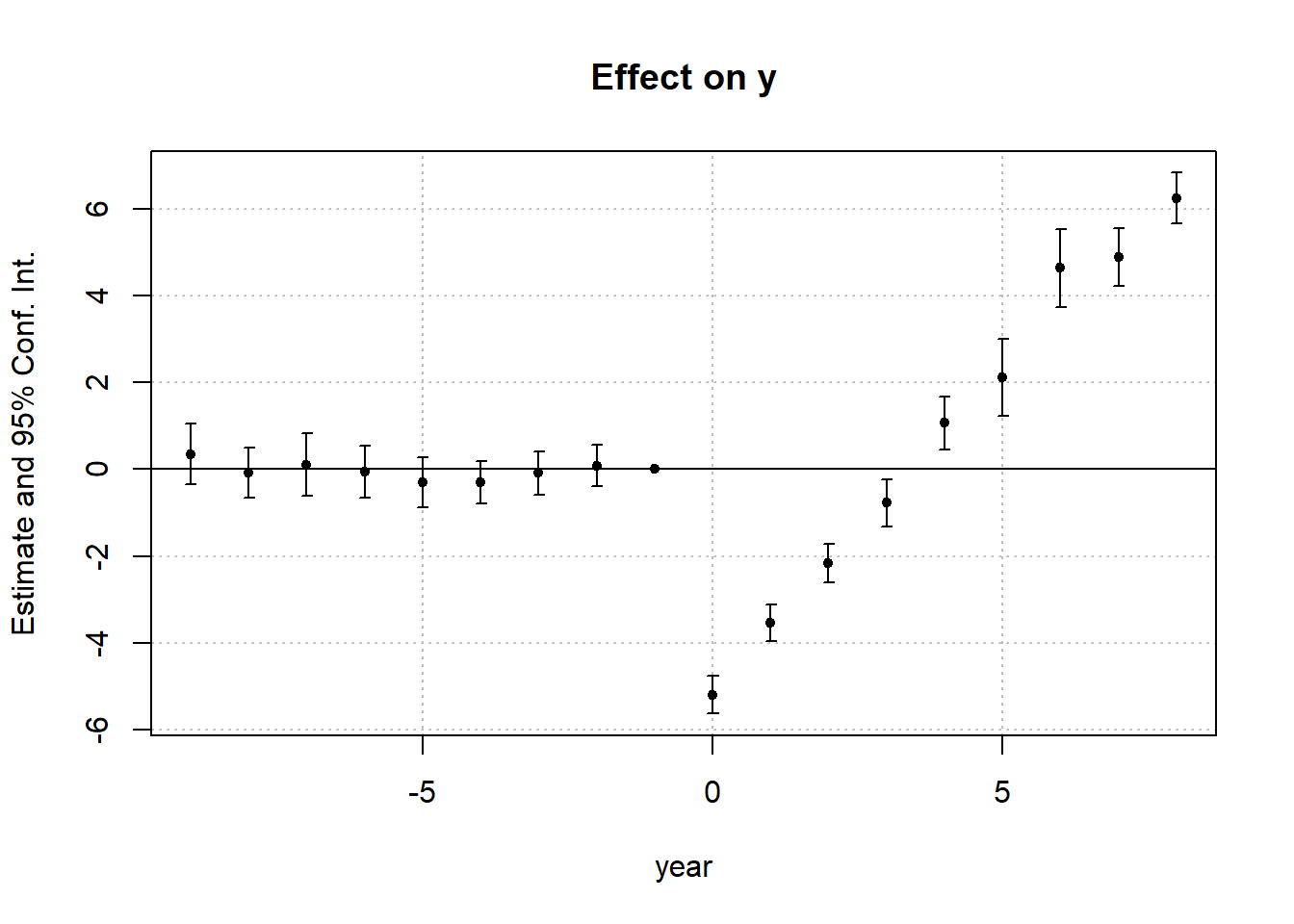

By interacting this factor variable, we can examine the dynamic effect of treatment (i.e., whether it’s fading or intensifying)

\[ \begin{aligned} Y &= \alpha_0 + \alpha_1 Group + \alpha_2 Time \\ &+ \beta_{-T_1} Treatment+ \beta_{-(T_1 -1)} Treatment + \dots + \beta_{-1} Treatment \\ &+ \beta_1 + \dots + \beta_{T_2} Treatment \end{aligned} \]

where

\(\beta_0\) is used as the reference group (i.e., drop from the model)

\(T_1\) is the pre-treatment period

\(T_2\) is the post-treatment period

With more variables (i.e., interaction terms), coefficients estimates can be less precise (i.e., higher SE).

- DiD on the relationship, not levels. Technically, we can apply DiD research design not only on variables, but also on coefficients estimates of some other regression models with before and after a policy is implemented.

Goal:

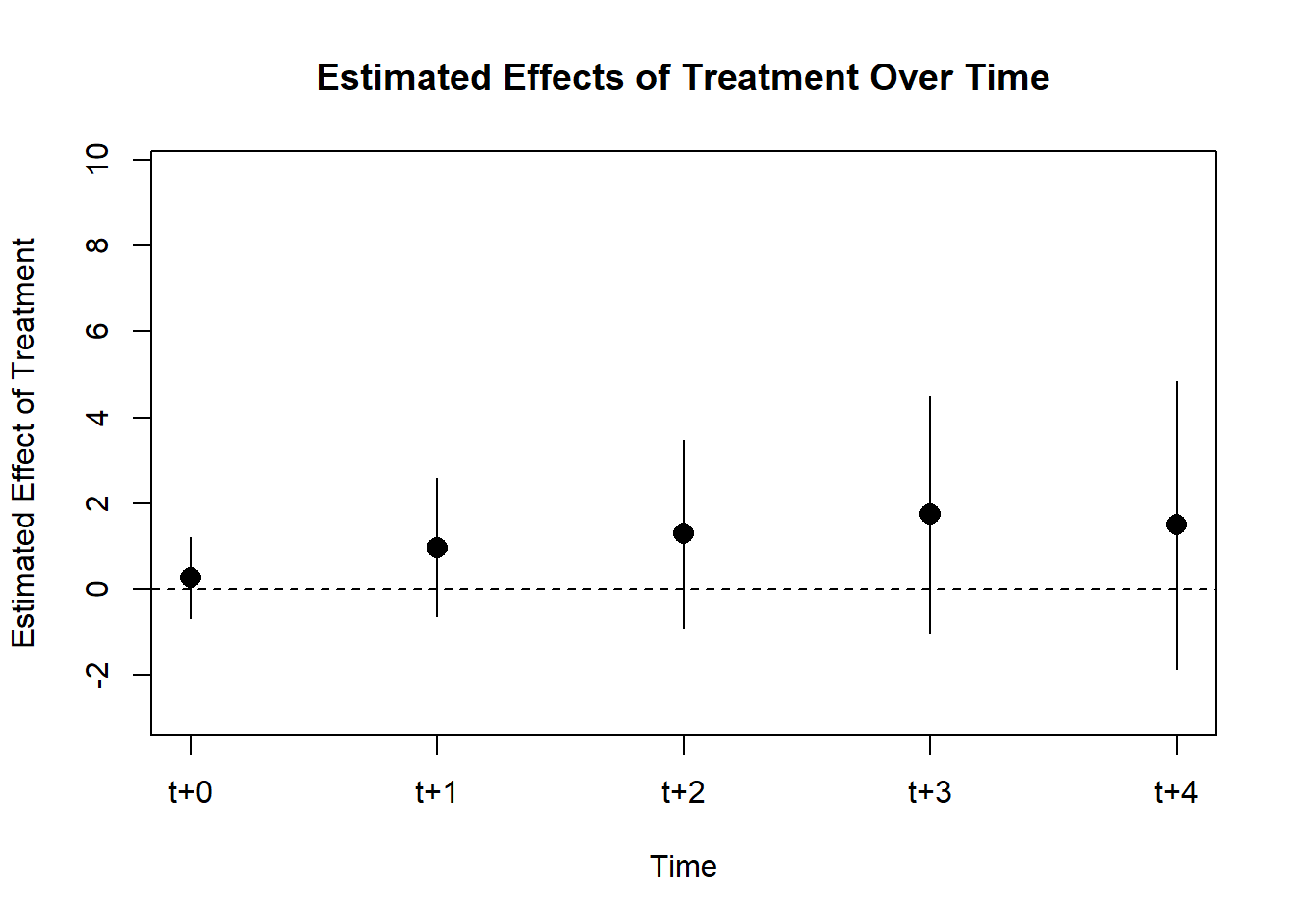

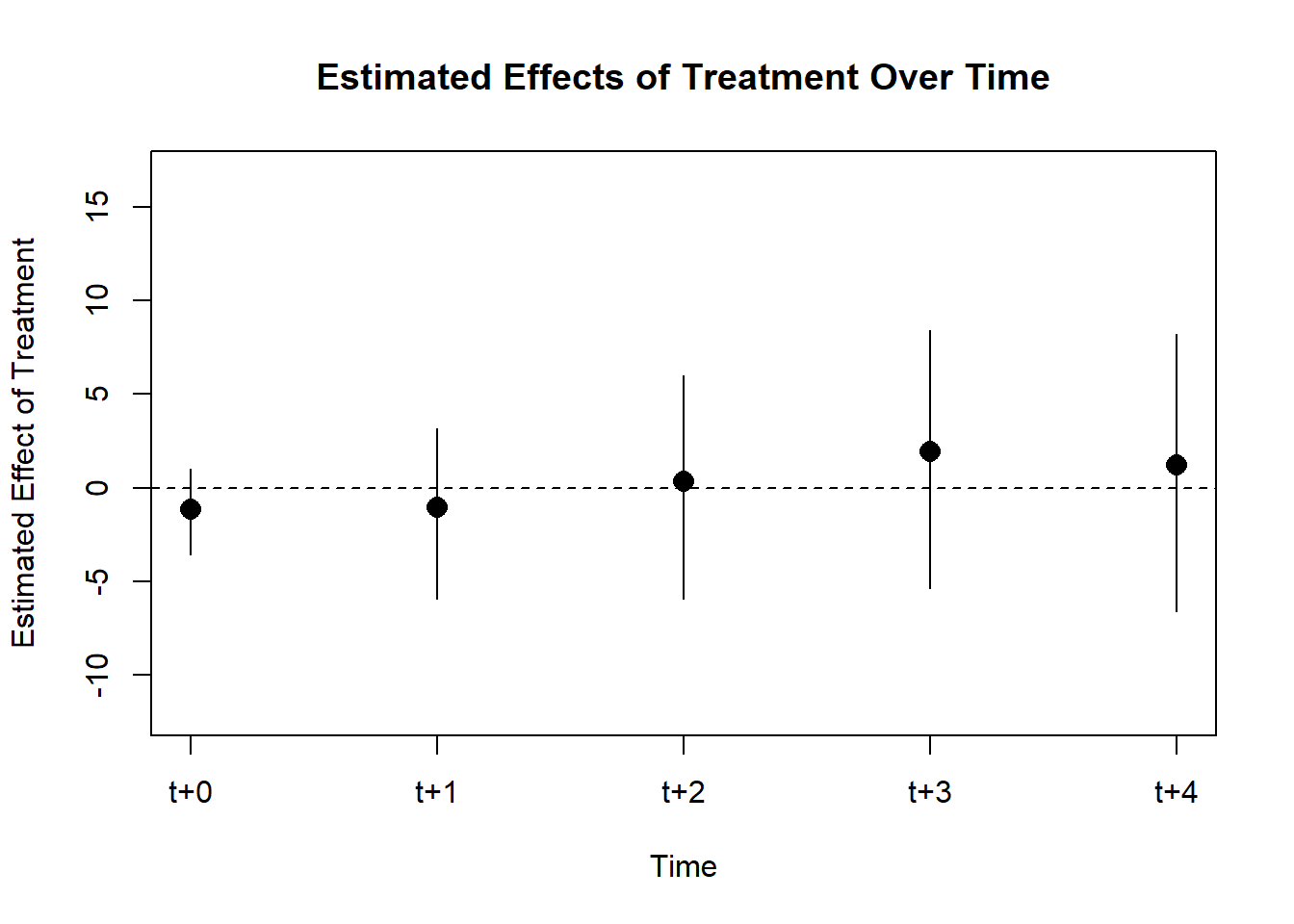

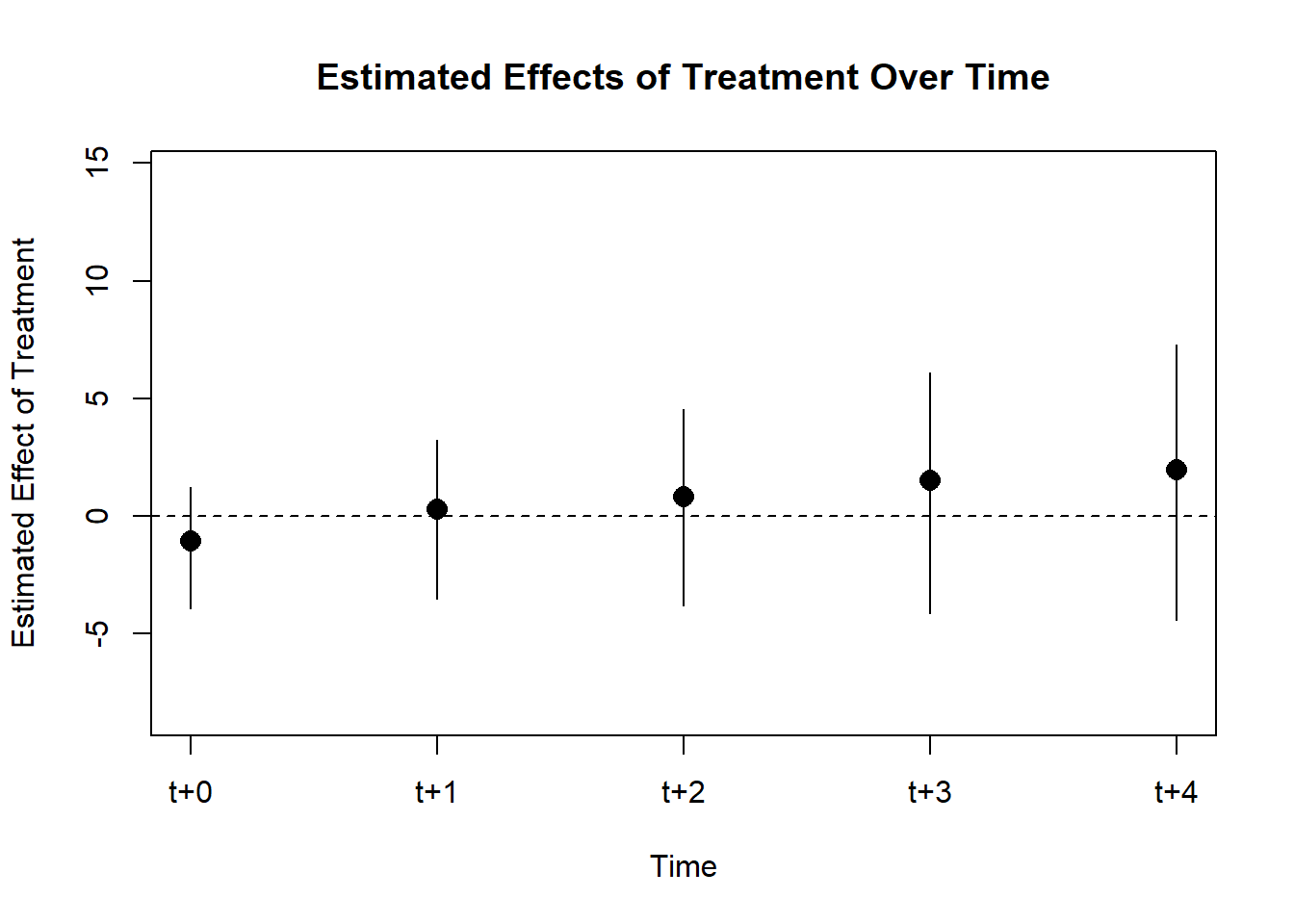

- Pre-treatment coefficients should be non-significant \(\beta_{-T_1}, \dots, \beta_{-1} = 0\) (similar to the Placebo Test)

- Post-treatment coefficients are expected to be significant \(\beta_1, \dots, \beta_{T_2} \neq0\)

- You can now examine the trend in post-treatment coefficients (i.e., increasing or decreasing)

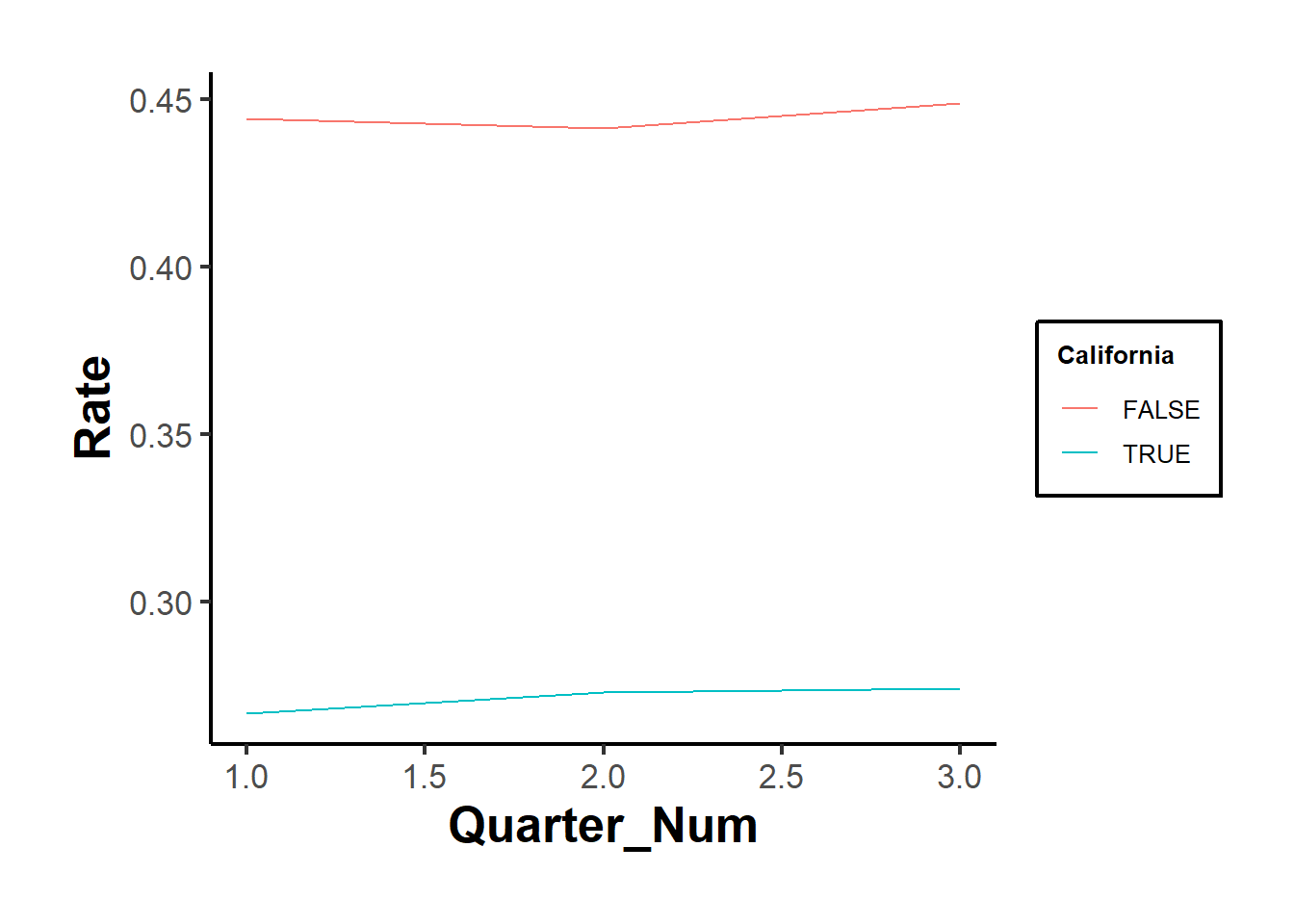

library(tidyverse)

library(fixest)

od <- causaldata::organ_donations %>%

# Treatment variable

dplyr::mutate(California = State == 'California') %>%

# centered time variable

dplyr::mutate(center_time = as.factor(Quarter_Num - 3))

# where 3 is the reference period precedes the treatment period

class(od$California)

#> [1] "logical"

class(od$State)

#> [1] "character"

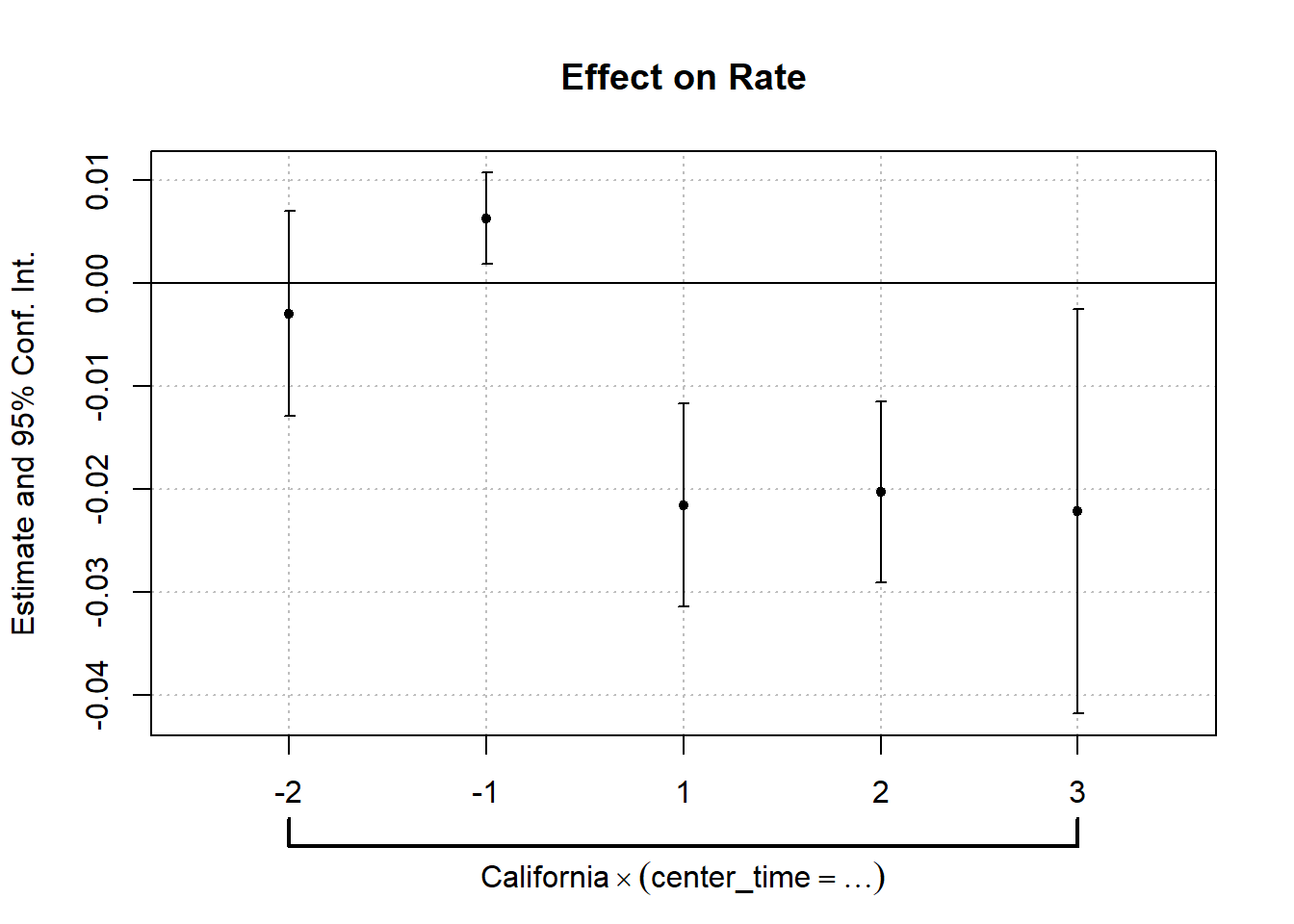

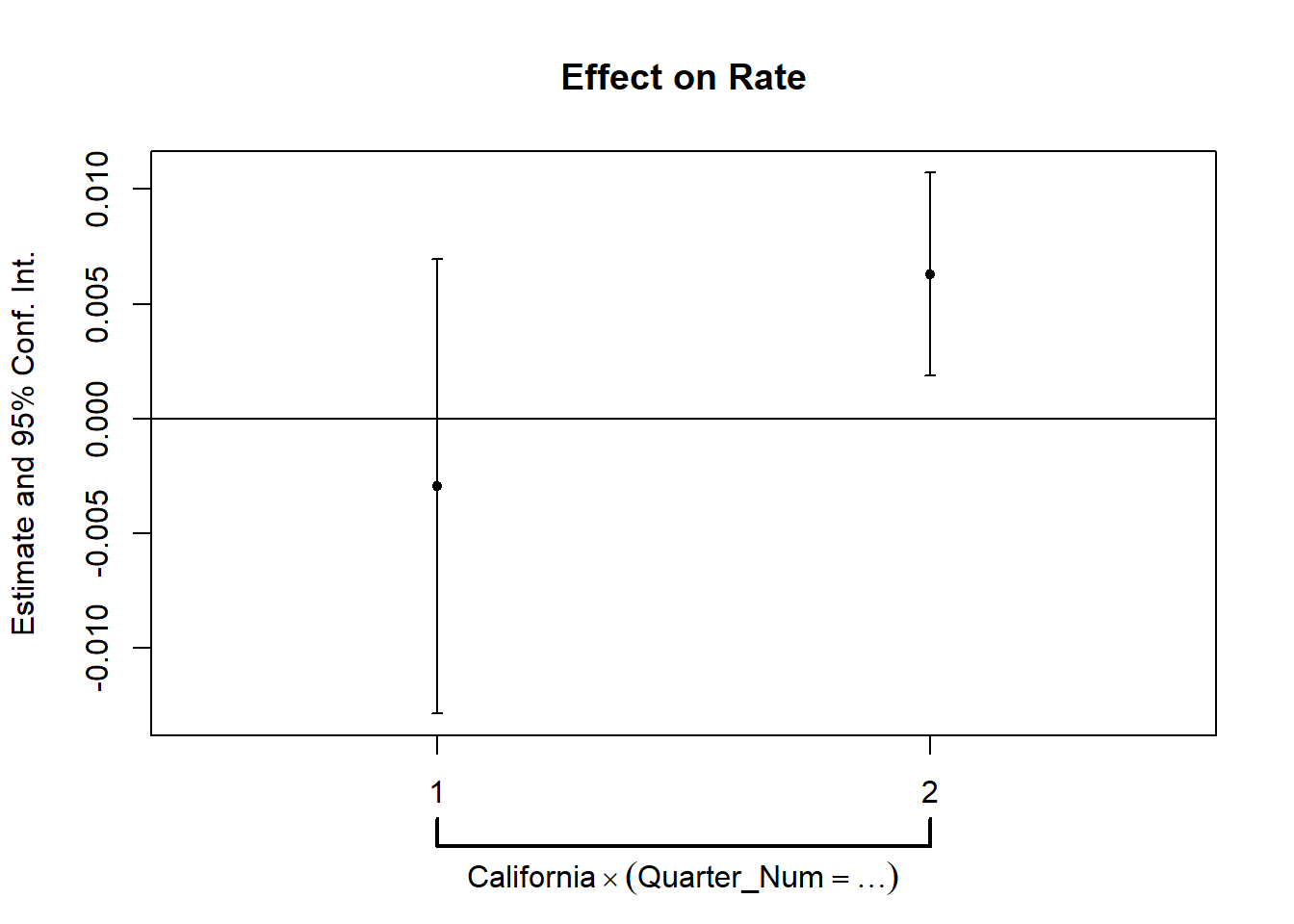

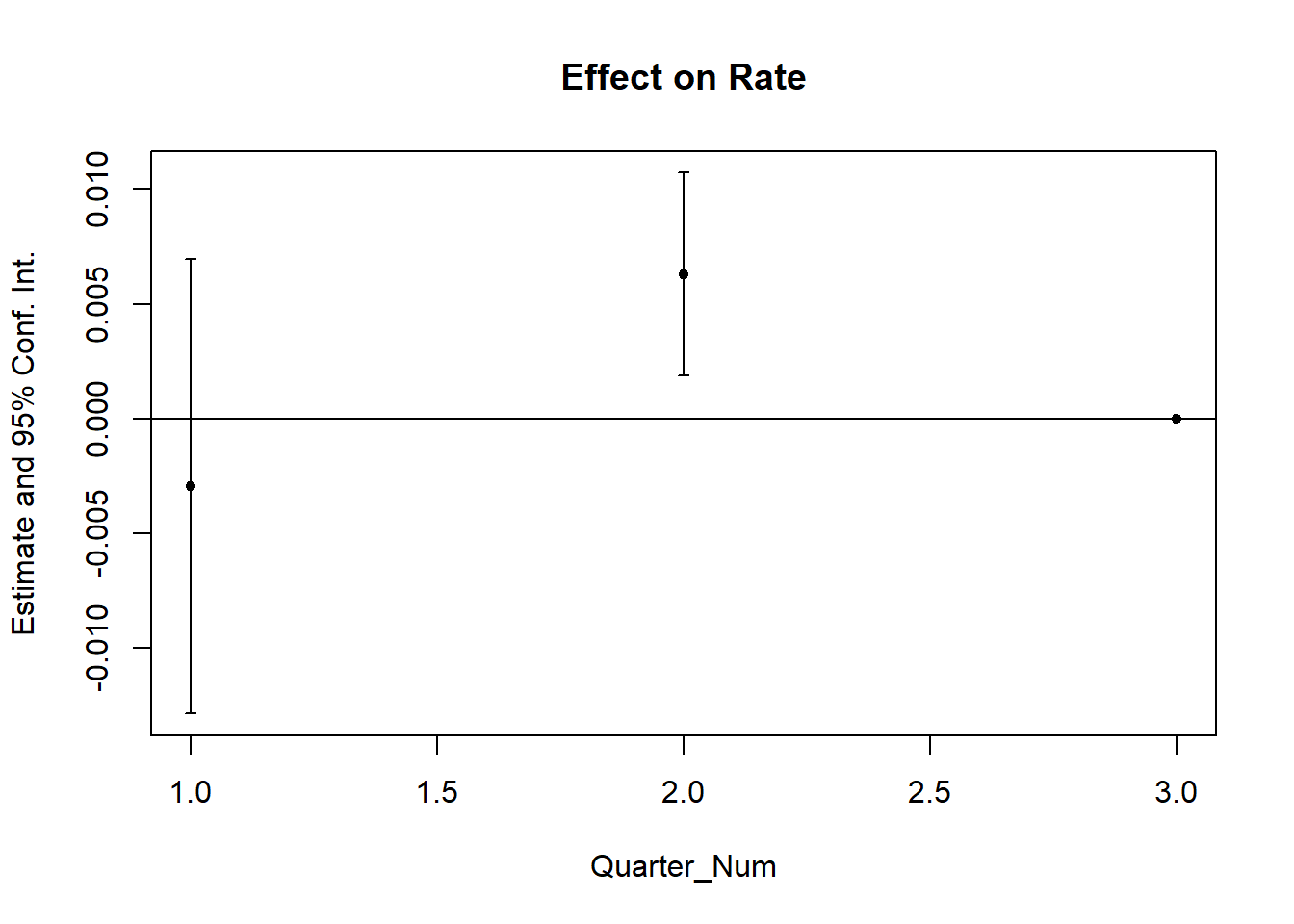

cali <- feols(Rate ~ i(center_time, California, ref = 0) |

State + center_time,

data = od)

etable(cali)

#> cali

#> Dependent Var.: Rate

#>

#> California x center_time = -2 -0.0029 (0.0051)

#> California x center_time = -1 0.0063** (0.0023)

#> California x center_time = 1 -0.0216*** (0.0050)

#> California x center_time = 2 -0.0203*** (0.0045)

#> California x center_time = 3 -0.0222* (0.0100)

#> Fixed-Effects: -------------------

#> State Yes

#> center_time Yes

#> _____________________________ ___________________

#> S.E.: Clustered by: State

#> Observations 162

#> R2 0.97934

#> Within R2 0.00979

#> ---

#> Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

iplot(cali, pt.join = T)

coefplot(cali)

26.3 Notes

-

Match treatment and control based on pre-treatment observables

Modify SEs appropriately (James J. Heckman, Ichimura, and Todd 1997). It’s might be easier to just use the Doubly Robust DiD (Sant’Anna and Zhao 2020) where you just need either matching or regression to work in order to identify your treatment effect

Whereas the group fixed effects control for the group time-invariant effects, it does not control for selection bias (i.e., certain groups are more likely to be treated than others). Hence, with these backdoor open (i.e., selection bias) between (1) propensity to be treated and (2) dynamics evolution of the outcome post-treatment, matching can potential close these backdoor.

Be careful when matching time-varying covariates because you might encounter “regression to the mean” problem, where pre-treatment periods can have an unusually bad or good time (that is out of the ordinary), then the post-treatment period outcome can just be an artifact of the regression to the mean (Daw and Hatfield 2018). This problem is not of concern to time-invariant variables.

Matching and DiD can use pre-treatment outcomes to correct for selection bias. From real world data and simulation, (Chabé-Ferret 2015) found that matching generally underestimates the average causal effect and gets closer to the true effect with more number of pre-treatment outcomes. When selection bias is symmetric around the treatment date, DID is still consistent when implemented symmetrically (i.e., the same number of period before and after treatment). In cases where selection bias is asymmetric, the MC simulations show that Symmetric DiD still performs better than Matching.

-

It’s always good to show results with and without controls because

If the controls are fixed within group or within time, then those should be absorbed under those fixed effects

If the controls are dynamic across group and across, then your parallel trends assumption is not plausible.

Under causal inference, \(R^2\) is not so important.

For count data, one can use the fixed-effects Poisson pseudo-maximum likelihood estimator (PPML) Puhani (2012) (For applied papers, see Burtch, Carnahan, and Greenwood (2018) in management and C. He et al. (2021) in marketing). This also allows for robust standard errors under over-dispersion (Wooldridge 1999).

This estimator outperforms a log OLS when data have many 0s(Silva and Tenreyro 2011), since log-OLS can produce biased estimates (O’Hara and Kotze 2010) under heteroskedascity (Silva and Tenreyro 2006).

For those thinking of negative binomial with fixed effects, there isn’t an estimator right now (Allison and Waterman 2002).

For [Zero-valued Outcomes], we have to distinguish the treatment effect on the intensive (outcome: 10 to 11) vs. extensive margins (outcome: 0 to 1), and we can’t readily interpret the treatment coefficient of log-transformed outcome regression as percentage change (J. Chen and Roth 2023). Alternatively, we can either focus on

-

Proportional treatment effects: \(\theta_{ATT\%} = \frac{E(Y_{it}(1) | D_i = 1, Post_t = 1) - E(Y_{it}(0) |D_i = 1, Post_t = 1)}{E(Y_{it}(0) | D_i = 1 , Post_t = 1}\) (i.e., percentage change in treated group’s average post-treatment outcome). Instead of relying on the parallel trends assumption in levels, we could also rely on parallel trends assumption in ratio (Wooldridge 2023).

We can use Poisson QMLE to estimate the treatment effect: \(Y_{it} = \exp(\beta_0 + D_i \times \beta_1 Post_t + \beta_2 D_i + \beta_3 Post_t + X_{it}) \epsilon_{it}\) and \(\hat{\theta}_{ATT \%} = \exp(\hat{\beta}_1-1)\).

To examine the parallel trends assumption in ratio holds, we can also estimate a dynamic version of the Poisson QMLE: \(Y_{it} = \exp(\lambda_t + \beta_2 D_i + \sum_{r \neq -1} \beta_r D_i \times (RelativeTime_t = r)\), we would expect \(\exp(\hat{\beta_r}) - 1 = 0\) for \(r < 0\).

Even if we see the plot of these coefficients are 0, we still should run sensitivity analysis (Rambachan and Roth 2023) to examine violation of this assumption (see Prior Parallel Trends Test).

Log Effects with Calibrated Extensive-margin value: due to problem with the mean value interpretation of the proportional treatment effects with outcomes that are heavy-tailed, we might be interested in the extensive margin effect. Then, we can explicit model how much weight we put on the intensive vs. extensive margin (J. Chen and Roth 2023, 39).

- Proportional treatment effects

set.seed(123) # For reproducibility

n <- 500 # Number of observations per group (treated and control)

# Generating IDs for a panel setup

ID <- rep(1:n, times = 2)

# Defining groups and periods

Group <- rep(c("Control", "Treated"), each = n)

Time <- rep(c("Before", "After"), times = n)

Treatment <- ifelse(Group == "Treated", 1, 0)

Post <- ifelse(Time == "After", 1, 0)

# Step 1: Generate baseline outcomes with a zero-inflated model

lambda <- 20 # Average rate of occurrence

zero_inflation <- 0.5 # Proportion of zeros

Y_baseline <-

ifelse(runif(2 * n) < zero_inflation, 0, rpois(2 * n, lambda))

# Step 2: Apply DiD treatment effect on the treated group in the post-treatment period

Treatment_Effect <- Treatment * Post

Y_treatment <-

ifelse(Treatment_Effect == 1, rpois(n, lambda = 2), 0)

# Incorporating a simple time trend, ensuring outcomes are non-negative

Time_Trend <- ifelse(Time == "After", rpois(2 * n, lambda = 1), 0)

# Step 3: Combine to get the observed outcomes

Y_observed <- Y_baseline + Y_treatment + Time_Trend

# Ensure no negative outcomes after the time trend

Y_observed <- ifelse(Y_observed < 0, 0, Y_observed)

# Create the final dataset

data <-

data.frame(

ID = ID,

Treatment = Treatment,

Period = Post,

Outcome = Y_observed

)

# Viewing the first few rows of the dataset

head(data)

#> ID Treatment Period Outcome

#> 1 1 0 0 0

#> 2 2 0 1 25

#> 3 3 0 0 0

#> 4 4 0 1 20

#> 5 5 0 0 19

#> 6 6 0 1 0

library(fixest)

res_pois <-

fepois(Outcome ~ Treatment + Period + Treatment * Period,

data = data,

vcov = "hetero")

etable(res_pois)

#> res_pois

#> Dependent Var.: Outcome

#>

#> Constant 2.249*** (0.0717)

#> Treatment 0.1743. (0.0932)

#> Period 0.0662 (0.0960)

#> Treatment x Period 0.0314 (0.1249)

#> __________________ _________________

#> S.E. type Heteroskeda.-rob.

#> Observations 1,000

#> Squared Cor. 0.01148

#> Pseudo R2 0.00746

#> BIC 15,636.8

#> ---

#> Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

# Average percentage change

exp(coefficients(res_pois)["Treatment:Period"]) - 1

#> Treatment:Period

#> 0.03191643

# SE using delta method

exp(coefficients(res_pois)["Treatment:Period"]) *

sqrt(res_pois$cov.scaled["Treatment:Period", "Treatment:Period"])

#> Treatment:Period

#> 0.1288596In this example, the DID coefficient is not significant. However, say that it’s significant, we can interpret the coefficient as 3 percent increase in posttreatment period due to the treatment.

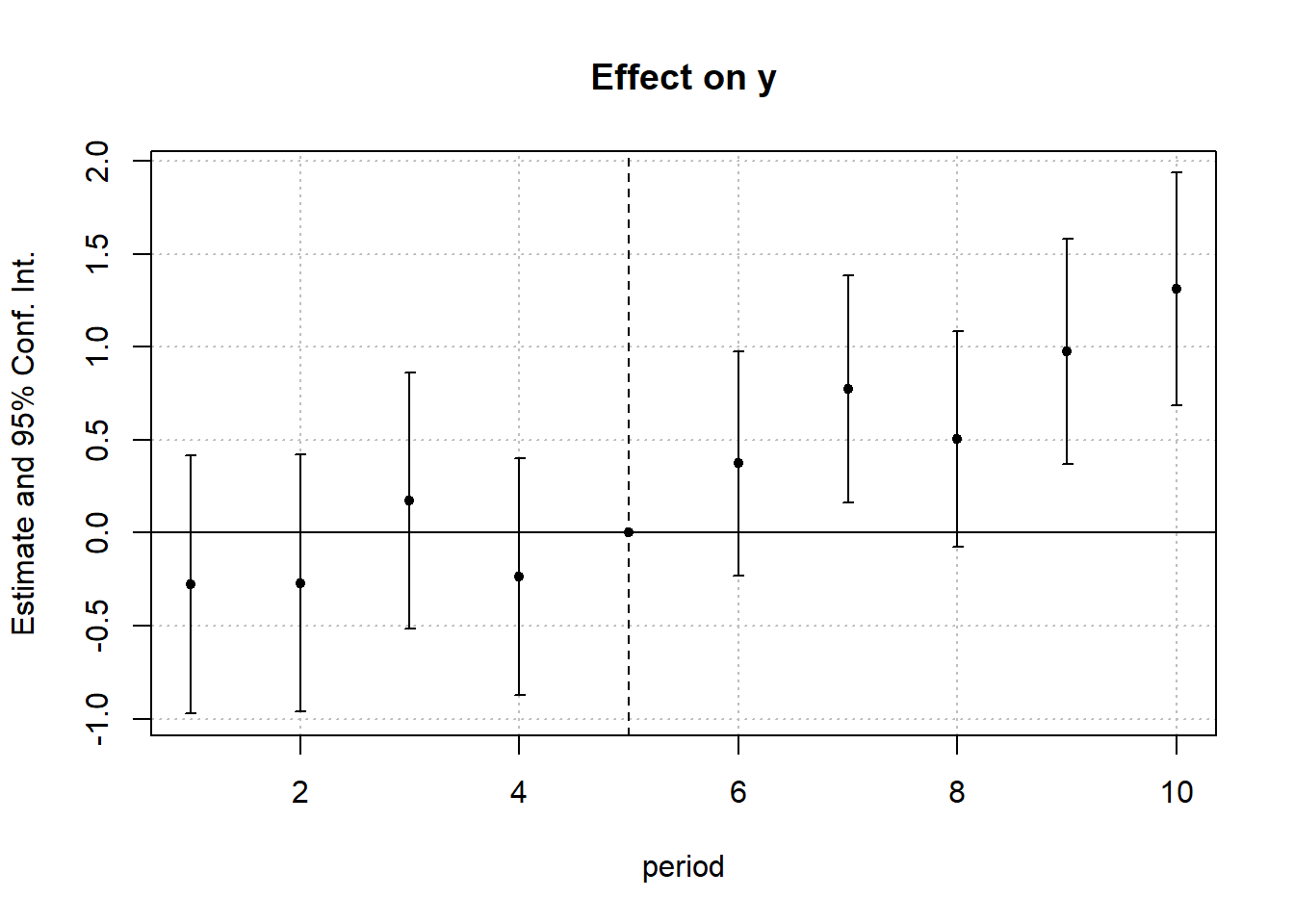

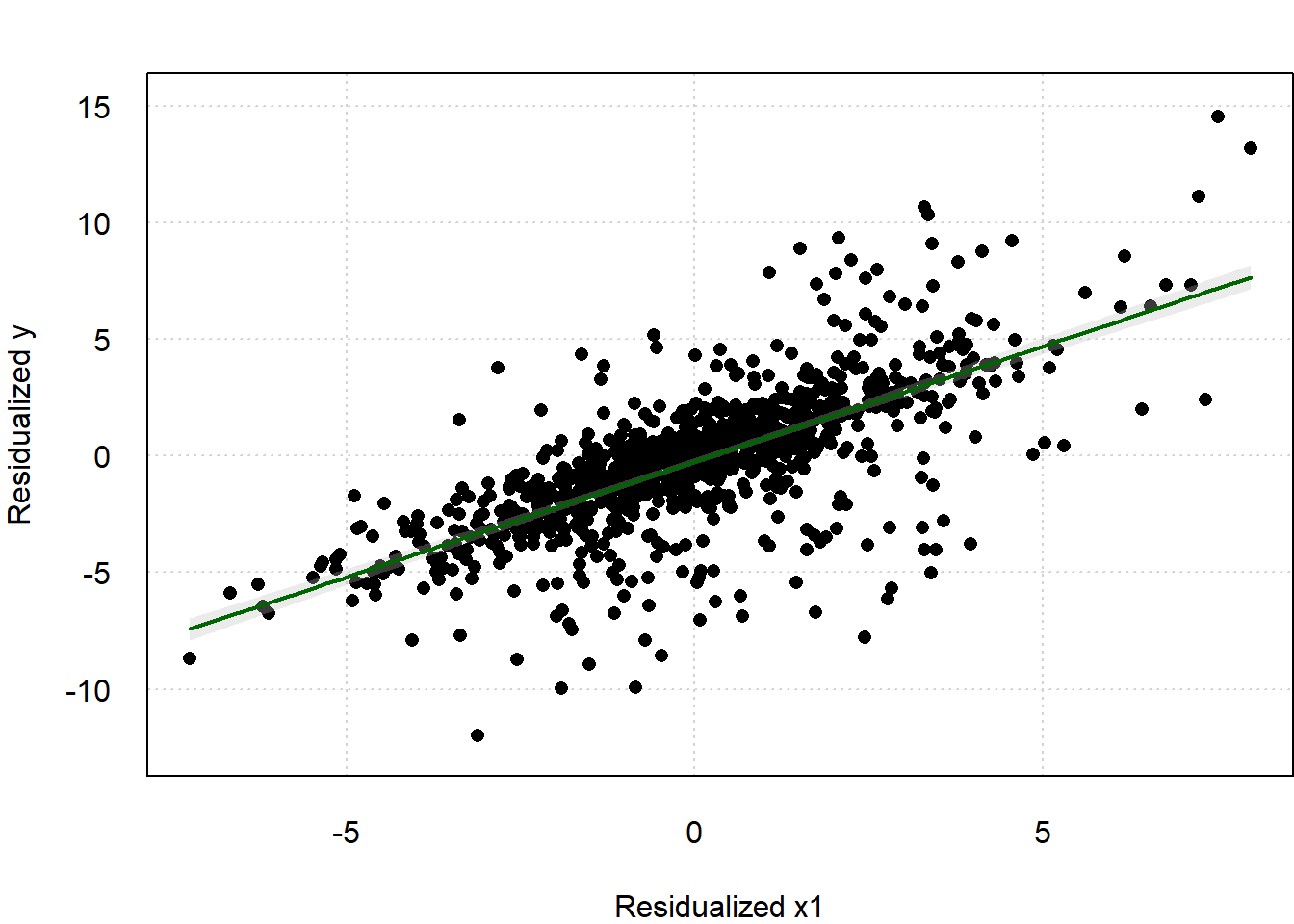

library(fixest)

base_did_log0 <- base_did |>

mutate(y = if_else(y > 0, y, 0))

res_pois_es <-

fepois(y ~ x1 + i(period, treat, 5) | id + period,

data = base_did_log0,

vcov = "hetero")

etable(res_pois_es)

#> res_pois_es

#> Dependent Var.: y

#>

#> x1 0.1895*** (0.0108)

#> treat x period = 1 -0.2769 (0.3545)

#> treat x period = 2 -0.2699 (0.3533)

#> treat x period = 3 0.1737 (0.3520)

#> treat x period = 4 -0.2381 (0.3249)

#> treat x period = 6 0.3724 (0.3086)

#> treat x period = 7 0.7739* (0.3117)

#> treat x period = 8 0.5028. (0.2962)

#> treat x period = 9 0.9746** (0.3092)

#> treat x period = 10 1.310*** (0.3193)

#> Fixed-Effects: ------------------

#> id Yes

#> period Yes

#> ___________________ __________________

#> S.E. type Heteroskedas.-rob.

#> Observations 1,080

#> Squared Cor. 0.51131

#> Pseudo R2 0.34836

#> BIC 5,868.8

#> ---

#> Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

iplot(res_pois_es)

This parallel trend is the “ratio” version as in Wooldridge (2023) :

\[ \frac{E(Y_{it}(0) |D_i = 1, Post_t = 1)}{E(Y_{it}(0) |D_i = 1, Post_t = 0)} = \frac{E(Y_{it}(0) |D_i = 0, Post_t = 1)}{E(Y_{it}(0) |D_i =0, Post_t = 0)} \]

which means without treatment, the average percentage change in the mean outcome for treated group is identical to that of the control group.

- Log Effects with Calibrated Extensive-margin value

If we want to study the treatment effect on a concave transformation of the outcome that is less influenced by those in the distribution’s tail, then we can perform this analysis.

Steps:

- Normalize the outcomes such that 1 represents the minimum non-zero and positve value (i.e., divide the outcome by its minimum non-zero and positive value).

- Estimate the treatment effects for the new outcome

\[ m(y) = \begin{cases} \log(y) & \text{for } y >0 \\ -x & \text{for } y = 0 \end{cases} \]

The choice of \(x\) depends on what the researcher is interested in:

| Value of \(x\) | Interest |

|---|---|

| \(x = 0\) | The treatment effect in logs where all zero-valued outcomes are set to equal the minimum non-zero value (i.e., we exclude the extensive-margin change between 0 and \(y_{min}\) ) |

| \(x>0\) | Setting the change between 0 and \(y_{min}\) to be valued as the equivalent of a \(x\) log point change along the intensive margin. |

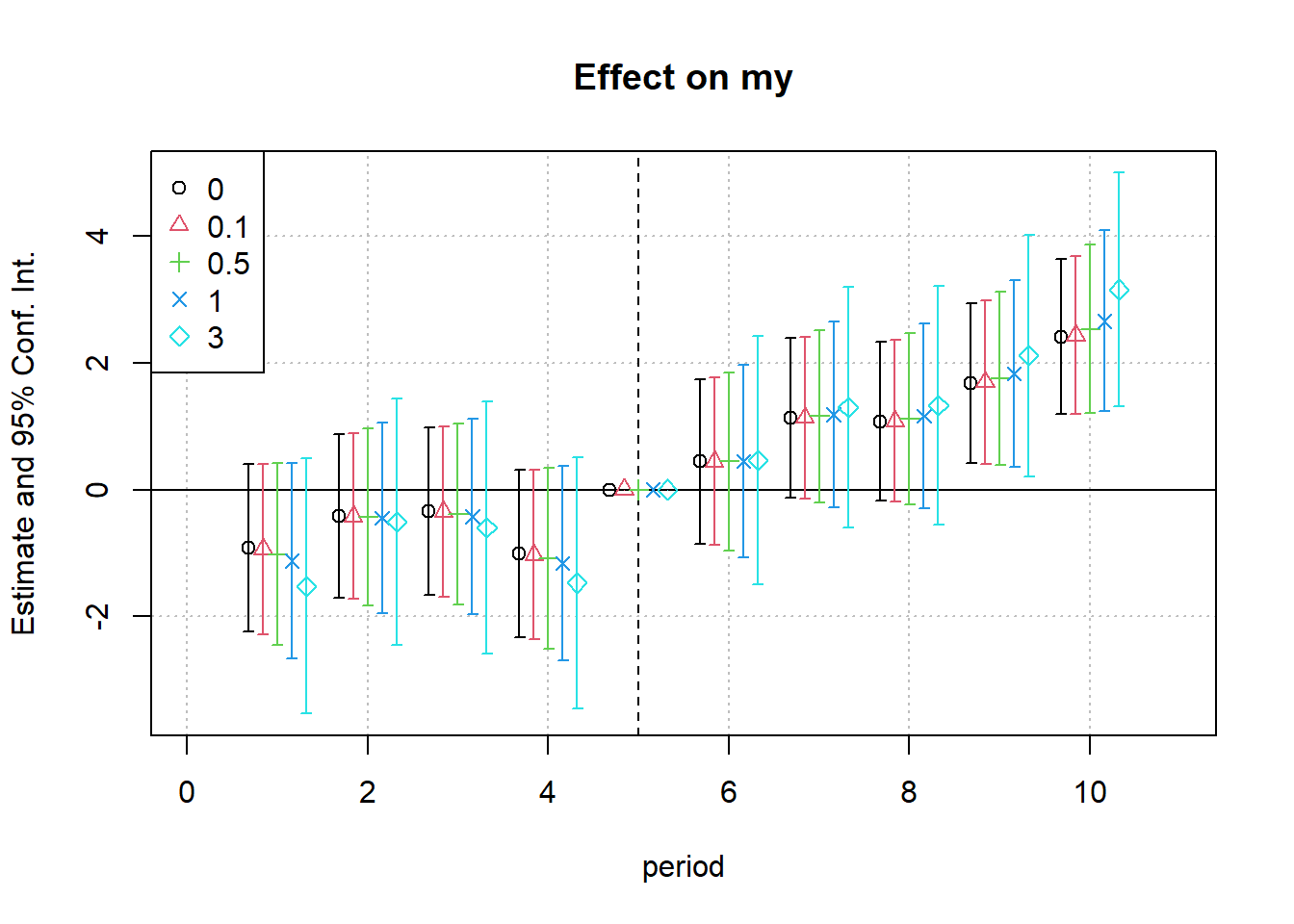

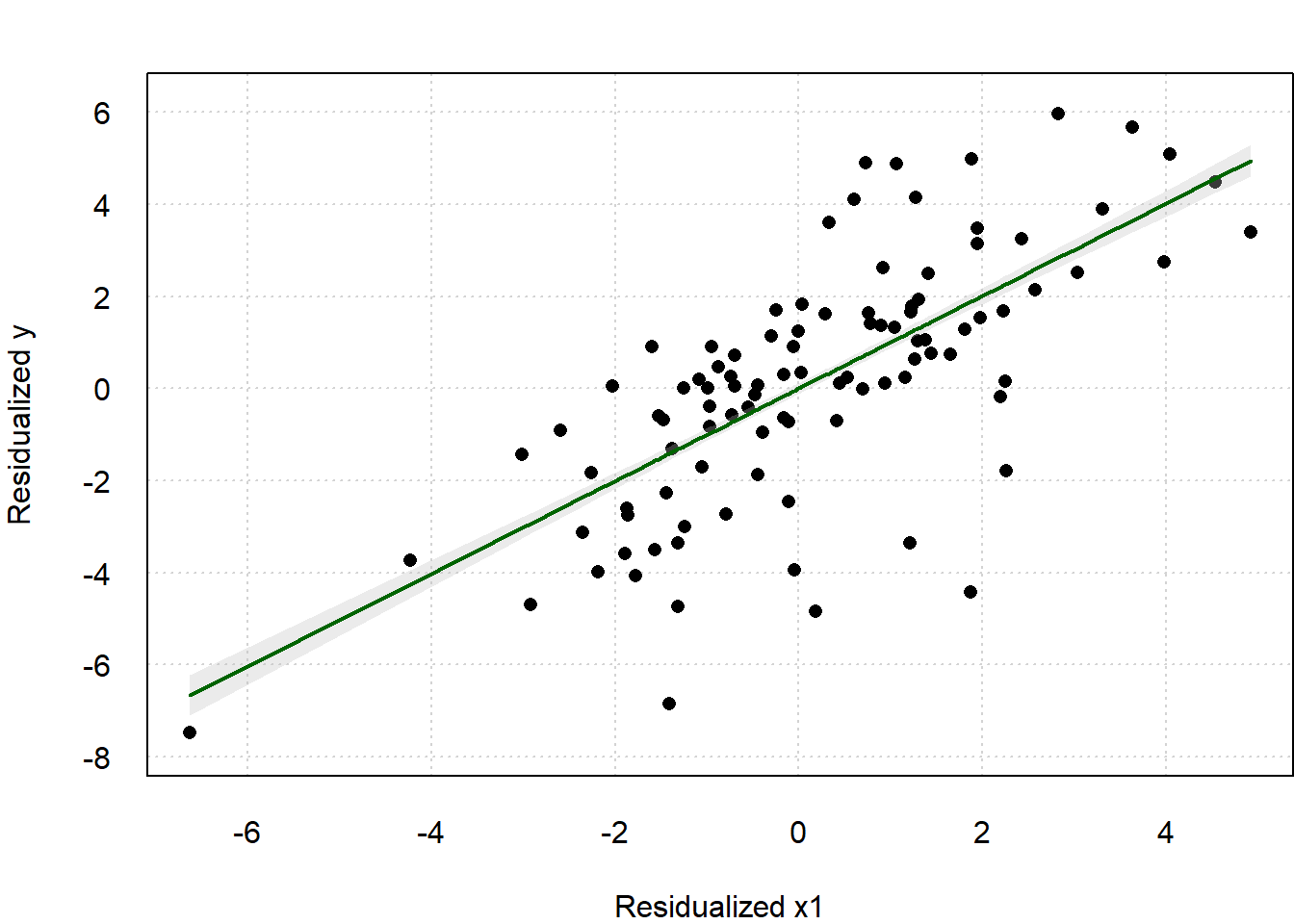

library(fixest)

base_did_log0_cali <- base_did_log0 |>

# get min

mutate(min_y = min(y[y > 0])) |>

# normalized the outcome

mutate(y_norm = y / min_y)

my_regression <-

function(x) {

base_did_log0_cali <-

base_did_log0_cali %>% mutate(my = ifelse(y_norm == 0,-x,

log(y_norm)))

my_reg <-

feols(

fml = my ~ x1 + i(period, treat, 5) | id + period,

data = base_did_log0_cali,

vcov = "hetero"

)

return(my_reg)

}

xvec <- c(0, .1, .5, 1, 3)

reg_list <- purrr::map(.x = xvec, .f = my_regression)

iplot(reg_list,

pt.col = 1:length(xvec),

pt.pch = 1:length(xvec))

legend("topleft",

col = 1:length(xvec),

pch = 1:length(xvec),

legend = as.character(xvec))

etable(

reg_list,

headers = list("Extensive-margin value (x)" = as.character(xvec)),

digits = 2,

digits.stats = 2

)

#> model 1 model 2 model 3

#> Extensive-margin value (x) 0 0.1 0.5

#> Dependent Var.: my my my

#>

#> x1 0.43*** (0.02) 0.44*** (0.02) 0.46*** (0.03)

#> treat x period = 1 -0.92 (0.67) -0.94 (0.69) -1.0 (0.73)

#> treat x period = 2 -0.41 (0.66) -0.42 (0.67) -0.43 (0.71)

#> treat x period = 3 -0.34 (0.67) -0.35 (0.68) -0.38 (0.73)

#> treat x period = 4 -1.0 (0.67) -1.0 (0.68) -1.1 (0.73)

#> treat x period = 6 0.44 (0.66) 0.44 (0.67) 0.45 (0.72)

#> treat x period = 7 1.1. (0.64) 1.1. (0.65) 1.2. (0.70)

#> treat x period = 8 1.1. (0.64) 1.1. (0.65) 1.1 (0.69)

#> treat x period = 9 1.7** (0.65) 1.7** (0.66) 1.8* (0.70)

#> treat x period = 10 2.4*** (0.62) 2.4*** (0.63) 2.5*** (0.68)

#> Fixed-Effects: -------------- -------------- --------------

#> id Yes Yes Yes

#> period Yes Yes Yes

#> __________________________ ______________ ______________ ______________

#> S.E. type Heterosk.-rob. Heterosk.-rob. Heterosk.-rob.

#> Observations 1,080 1,080 1,080

#> R2 0.43 0.43 0.43

#> Within R2 0.26 0.26 0.25

#>

#> model 4 model 5

#> Extensive-margin value (x) 1 3

#> Dependent Var.: my my

#>

#> x1 0.49*** (0.03) 0.62*** (0.04)

#> treat x period = 1 -1.1 (0.79) -1.5 (1.0)

#> treat x period = 2 -0.44 (0.77) -0.51 (0.99)

#> treat x period = 3 -0.43 (0.78) -0.60 (1.0)

#> treat x period = 4 -1.2 (0.78) -1.5 (1.0)

#> treat x period = 6 0.45 (0.77) 0.46 (1.0)

#> treat x period = 7 1.2 (0.75) 1.3 (0.97)

#> treat x period = 8 1.2 (0.74) 1.3 (0.96)

#> treat x period = 9 1.8* (0.75) 2.1* (0.97)

#> treat x period = 10 2.7*** (0.73) 3.2*** (0.94)

#> Fixed-Effects: -------------- --------------

#> id Yes Yes

#> period Yes Yes

#> __________________________ ______________ ______________

#> S.E. type Heterosk.-rob. Heterosk.-rob.

#> Observations 1,080 1,080

#> R2 0.42 0.41

#> Within R2 0.25 0.24

#> ---

#> Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1We have the dynamic treatment effects for different hypothesized extensive-margin value of \(x \in (0, .1, .5, 1, 3, 5)\)

The first column is when the zero-valued outcome equal to \(y_{min, y>0}\) (i.e., there is no different between the minimum outcome and zero outcome - \(x = 0\))

For this particular example, as the extensive margin increases, we see an increase in the effect magnitude. The second column is when we assume an extensive-margin change from 0 to \(y_{min, y >0}\) is equivalent to a 10 (i.e., \(0.1 \times 100\)) log point change along the intensive margin.

26.4 Standard Errors

Serial correlation is a big problem in DiD because (Bertrand, Duflo, and Mullainathan 2004)

- DiD often uses long time series

- Outcomes are often highly positively serially correlated

- Minimal variation in the treatment variable over time within a group (e.g., state).

To overcome this problem:

- Using parametric correction (standard AR correction) is not good.

- Using nonparametric (e.g., block bootstrap- keep all obs from the same group such as state together) is good when number of groups is large.

- Remove time series dimension (i.e., aggregate data into 2 periods: pre and post). This still works with small number of groups (See (Donald and Lang 2007) for more notes on small-sample aggregation).

- Empirical and arbitrary variance-covariance matrix corrections work only in large samples.

26.5 Examples

Example by Philipp Leppert replicating Card and Krueger (1994)

Example by Anthony Schmidt

26.5.1 Example by Doleac and Hansen (2020)

The purpose of banning a checking box for ex-criminal was banned because we thought that it gives more access to felons

Even if we ban the box, employers wouldn’t just change their behaviors. But then the unintended consequence is that employers statistically discriminate based on race

3 types of ban the box

- Public employer only

- Private employer with government contract

- All employers

Main identification strategy

- If any county in the Metropolitan Statistical Area (MSA) adopts ban the box, it means the whole MSA is treated. Or if the state adopts “ban the ban,” every county is treated

Under Simple Dif-n-dif

\[ Y_{it} = \beta_0 + \beta_1 Post_t + \beta_2 treat_i + \beta_2 (Post_t \times Treat_i) + \epsilon_{it} \]

But if there is no common post time, then we should use Staggered Dif-n-dif

\[ \begin{aligned} E_{imrt} &= \alpha + \beta_1 BTB_{imt} W_{imt} + \beta_2 BTB_{mt} + \beta_3 BTB_{mt} H_{imt}\\ &+ \delta_m + D_{imt} \beta_5 + \lambda_{rt} + \delta_m\times f(t) \beta_7 + e_{imrt} \end{aligned} \]

where

\(i\) = person; \(m\) = MSA; \(r\) = region (US regions e.g., Midwest) ; \(r\) = region; \(t\) = year

\(W\) = White; \(B\) = Black; \(H\) = Hispanic

\(\beta_1 BTB_{imt} W_{imt} + \beta_2 BTB_{mt} + \beta_3 BTB_{mt} H_{imt}\) are the 3 dif-n-dif variables (\(BTB\) = “ban the box”)

\(\delta_m\) = dummy for MSI

\(D_{imt}\) = control for people

\(\lambda_{rt}\) = region by time fixed effect

\(\delta_m \times f(t)\) = linear time trend within MSA (but we should not need this if we have good pre-trend)

If we put \(\lambda_r - \lambda_t\) (separately) we will more broad fixed effect, while \(\lambda_{rt}\) will give us deeper and narrower fixed effect.

Before running this model, we have to drop all other races. And \(\beta_1, \beta_2, \beta_3\) are not collinear because there are all interaction terms with \(BTB_{mt}\)

If we just want to estimate the model for black men, we will modify it to be

\[ E_{imrt} = \alpha + BTB_{mt} \beta_1 + \delta_m + D_{imt} \beta_5 + \lambda_{rt} + (\delta_m \times f(t)) \beta_7 + e_{imrt} \]

\[ \begin{aligned} E_{imrt} &= \alpha + BTB_{m (t - 3t)} \theta_1 + BTB_{m(t-2)} \theta_2 + BTB_{mt} \theta_4 \\ &+ BTB_{m(t+1)}\theta_5 + BTB_{m(t+2)}\theta_6 + BTB_{m(t+3t)}\theta_7 \\ &+ [\delta_m + D_{imt}\beta_5 + \lambda_r + (\delta_m \times (f(t))\beta_7 + e_{imrt}] \end{aligned} \]

We have to leave \(BTB_{m(t-1)}\theta_3\) out for the category would not be perfect collinearity

So the year before BTB (\(\theta_1, \theta_2, \theta_3\)) should be similar to each other (i.e., same pre-trend). Remember, we only run for places with BTB.

If \(\theta_2\) is statistically different from \(\theta_3\) (baseline), then there could be a problem, but it could also make sense if we have pre-trend announcement.

26.5.2 Example from Princeton

library(foreign)

mydata = read.dta("http://dss.princeton.edu/training/Panel101.dta") %>%

# create a dummy variable to indicate the time when the treatment started

dplyr::mutate(time = ifelse(year >= 1994, 1, 0)) %>%

# create a dummy variable to identify the treatment group

dplyr::mutate(treated = ifelse(country == "E" |

country == "F" | country == "G" ,

1,

0)) %>%

# create an interaction between time and treated

dplyr::mutate(did = time * treated)estimate the DID estimator

didreg = lm(y ~ treated + time + did, data = mydata)

summary(didreg)

#>

#> Call:

#> lm(formula = y ~ treated + time + did, data = mydata)

#>

#> Residuals:

#> Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

#> -9.768e+09 -1.623e+09 1.167e+08 1.393e+09 6.807e+09

#>

#> Coefficients:

#> Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

#> (Intercept) 3.581e+08 7.382e+08 0.485 0.6292

#> treated 1.776e+09 1.128e+09 1.575 0.1200

#> time 2.289e+09 9.530e+08 2.402 0.0191 *

#> did -2.520e+09 1.456e+09 -1.731 0.0882 .

#> ---

#> Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

#>

#> Residual standard error: 2.953e+09 on 66 degrees of freedom

#> Multiple R-squared: 0.08273, Adjusted R-squared: 0.04104

#> F-statistic: 1.984 on 3 and 66 DF, p-value: 0.1249The did coefficient is the differences-in-differences estimator. Treat has a negative effect

26.5.3 Example by Card and Krueger (1993)

found that increase in minimum wage increases employment

Experimental Setting:

New Jersey (treatment) increased minimum wage

Penn (control) did not increase minimum wage

| After | Before | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment | NJ | A | B | A - B |

| Control | PA | C | D | C - D |

| A - C | B - D | (A - B) - (C - D) |

where

A - B = treatment effect + effect of time (additive)

C - D = effect of time

(A - B) - (C - D) = dif-n-dif

The identifying assumptions:

Can’t have switchers

-

PA is the control group

is a good counter factual

is what NJ would look like if they hadn’t had the treatment

\[ Y_{jt} = \beta_0 + NJ_j \beta_1 + POST_t \beta_2 + (NJ_j \times POST_t)\beta_3+ X_{jt}\beta_4 + \epsilon_{jt} \]

where

\(j\) = restaurant

\(NJ\) = dummy where \(1 = NJ\), and \(0 = PA\)

\(POST\) = dummy where \(1 = post\), and \(0 = pre\)

Notes:

We don’t need \(\beta_4\) in our model to have unbiased \(\beta_3\), but including it would give our coefficients efficiency

If we use \(\Delta Y_{jt}\) as the dependent variable, we don’t need \(POST_t \beta_2\) anymore

Alternative model specification is that the authors use NJ high wage restaurant as control group (still choose those that are close to the border)

The reason why they can’t control for everything (PA + NJ high wage) is because it’s hard to interpret the causal treatment

-

Dif-n-dif utilizes similarity in pretrend of the dependent variables. However, this is neither a necessary nor sufficient for the identifying assumption.

It’s not sufficient because they can have multiple treatments (technically, you could include more control, but your treatment can’t interact)

It’s not necessary because trends can be parallel after treatment

However, we can’t never be certain; we just try to find evidence consistent with our theory so that dif-n-dif can work.

Notice that we don’t need before treatment the levels of the dependent variable to be the same (e.g., same wage average in both NJ and PA), dif-n-dif only needs pre-trend (i.e., slope) to be the same for the two groups.

26.5.4 Example by Butcher, McEwan, and Weerapana (2014)

Theory:

-

Highest achieving students are usually in hard science. Why?

Hard to give students students the benefit of doubt for hard science

How unpleasant and how easy to get a job. Degrees with lower market value typically want to make you feel more pleasant

Under OLS

\[ E_{ij} = \beta_0 + X_i \beta_1 + G_j \beta_2 + \epsilon_{ij} \]

where

\(X_i\) = student attributes

\(\beta_2\) = causal estimate (from grade change)

\(E_{ij}\) = Did you choose to enroll in major \(j\)

\(G_j\) = grade given in major \(j\)

Examine \(\hat{\beta}_2\)

Negative bias: Endogenous response because department with lower enrollment rate will give better grade

Positive bias: hard science is already having best students (i.e., ability), so if they don’t their grades can be even lower

Under dif-n-dif

\[ Y_{idt} = \beta_0 + POST_t \beta_1 + Treat_d \beta_2 + (POST_t \times Treat_d)\beta_3 + X_{idt} + \epsilon_{idt} \]

where

- \(Y_{idt}\) = grade average

| Intercept | Treat | Post | Treat*Post | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treat Pre | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Treat Post | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Control Pre | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Control Post | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Average for pre-control \(\beta_0\) |

A more general specification of the dif-n-dif is that

\[ Y_{idt} = \alpha_0 + (POST_t \times Treat_d) \alpha_1 + \theta_d + \delta_t + X_{idt} + u_{idt} \]

where

\((\theta_d + \delta_t)\) richer , more df than \(Treat_d \beta_2 + Post_t \beta_1\) (because fixed effects subsume Post and treat)

\(\alpha_1\) should be equivalent to \(\beta_3\) (if your model assumptions are correct)

26.6 One Difference

The regression formula is as follows (Liaukonytė, Tuchman, and Zhu 2023):

\[ y_{ut} = \beta \text{Post}_t + \gamma_u + \gamma_w(t) + \gamma_l + \gamma_g(u)p(t) + \epsilon_{ut} \]

where

- \(y_{ut}\): Outcome of interest for unit u in time t.

- \(\text{Post}_t\): Dummy variable representing a specific post-event period.

- \(\beta\): Coefficient measuring the average change in the outcome after the event relative to the pre-period.

- \(\gamma_u\): Fixed effects for each unit.

- \(\gamma_w(t)\): Time-specific fixed effects to account for periodic variations.

- \(\gamma_l\): Dummy variable for a specific significant period (e.g., a major event change).

- \(\gamma_g(u)p(t)\): Group x period fixed effects for flexible trends that may vary across different categories (e.g., geographical regions) and periods.

- \(\epsilon_{ut}\): Error term.

This model can be used to analyze the impact of an event on the outcome of interest while controlling for various fixed effects and time-specific variations, but using units themselves pre-treatment as controls.

26.7 Two-way Fixed-effects

A generalization of the dif-n-dif model is the two-way fixed-effects models where you have multiple groups and time effects. But this is not a designed-based, non-parametric causal estimator (Imai and Kim 2021)

When applying TWFE to multiple groups and multiple periods, the supposedly causal coefficient is the weighted average of all two-group/two-period DiD estimators in the data where some of the weights can be negative. More specifically, the weights are proportional to group sizes and treatment indicator’s variation in each pair, where units in the middle of the panel have the highest weight.

The canonical/standard TWFE only works when

-

Effects are homogeneous across units and across time periods (i.e., no dynamic changes in the effects of treatment). See (Goodman-Bacon 2021; Clément De Chaisemartin and d’Haultfoeuille 2020; L. Sun and Abraham 2021; Borusyak, Jaravel, and Spiess 2021) for details. Similarly, it relies on the assumption of linear additive effects (Imai and Kim 2021)

Have to argue why treatment heterogeneity is not a problem (e.g., plot treatment timing and decompose treatment coefficient using Goodman-Bacon Decomposition) know the percentage of observation are never treated (because as the never-treated group increases, the bias of TWFE decreases, with 80% sample to be never-treated, bias is negligible). The problem is worsen when you have long-run effects.

Need to manually drop two relative time periods if everyone is eventually treated (to avoid multicollinearity). Programs might do this randomly and if it chooses to drop a post-treatment period, it will create biases. The choice usually -1, and -2 periods.

Treatment heterogeneity can come in because (1) it might take some time for a treatment to have measurable changes in outcomes or (2) for each period after treatment, the effect can be different (phase in or increasing effects).

2 time periods.

Within this setting, TWFE works because, using the baseline (e.g., control units where their treatment status is unchanged across time periods), the comparison can be

-

Good for

Newly treated units vs. control

Newly treated units vs not-yet treated

-

Bad for

- Newly treated vs. already treated (because already treated cannot serve as the potential outcome for the newly treated).

- Strict exogeneity (i.e., time-varying confounders, feedback from past outcome to treatment) (Imai and Kim 2019)

- Specific functional forms (i.e., treatment effect homogeneity and no carryover effects or anticipation effects) (Imai and Kim 2019)

Note: Notation for this section is consistent with (2020)

\[ Y_{it} = \alpha_i + \lambda_t + \tau W_{it} + \beta X_{it} + \epsilon_{it} \]

where

\(Y_{it}\) is the outcome

\(\alpha_i\) is the unit FE

\(\lambda_t\) is the time FE

\(\tau\) is the causal effect of treatment

\(W_{it}\) is the treatment indicator

\(X_{it}\) are covariates

When \(T = 2\), the TWFE is the traditional DiD model

Under the following assumption, \(\hat{\tau}_{OLS}\) is unbiased:

- homogeneous treatment effect

- parallel trends assumptions

- linear additive effects (Imai and Kim 2021)

Remedies for TWFE’s shortcomings

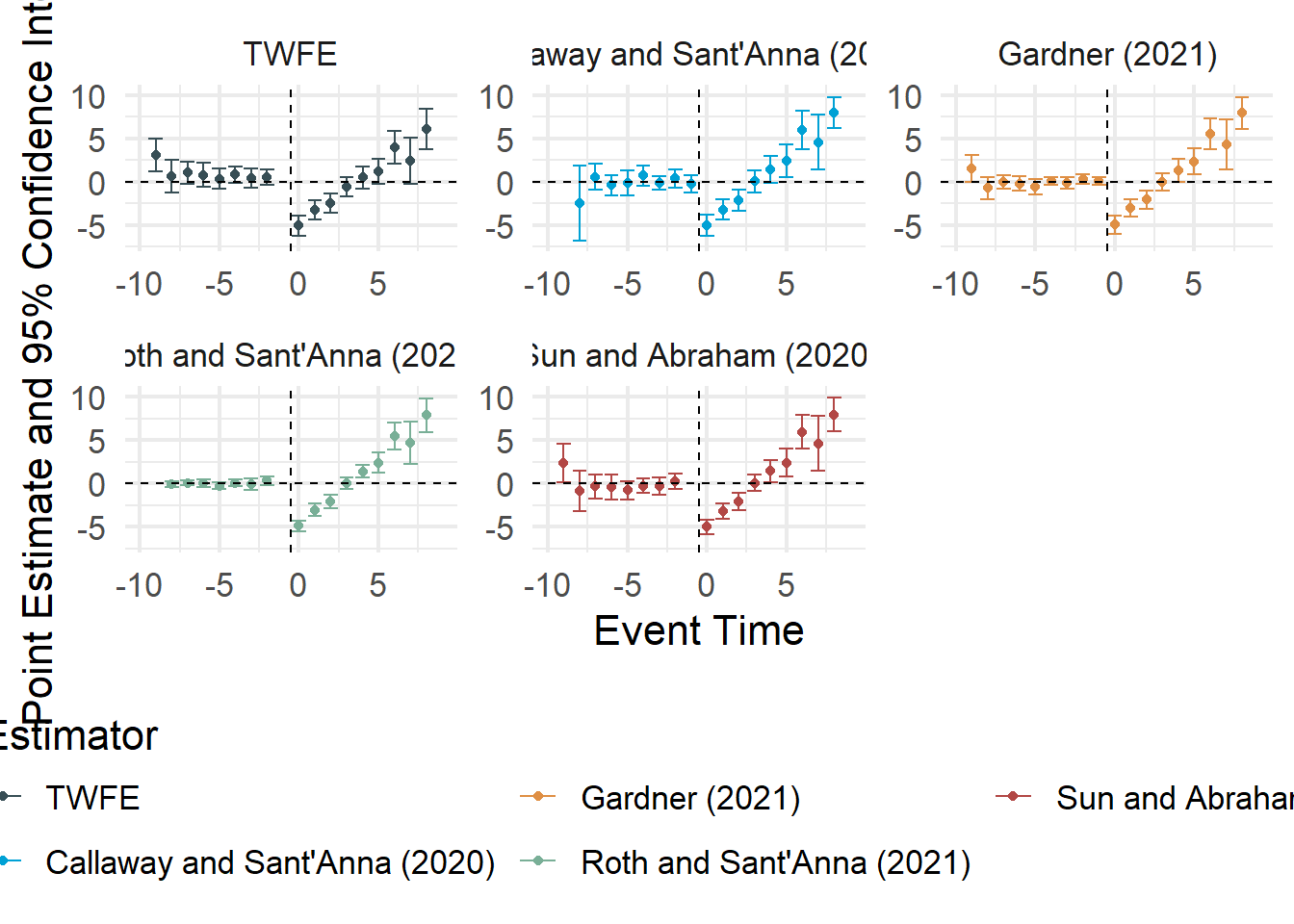

(Goodman-Bacon 2021): diagnostic robustness tests of the TWFE DiD and identify influential observations to the DiD estimate (Goodman-Bacon Decomposition)

-

(Callaway and Sant’Anna 2021): 2-step estimation with a bootstrap procedure that can account for autocorrelation and clustering,

the parameters of interest are the group-time average treatment effects, where each group is defined by when it was first treated (Multiple periods and variation in treatment timing)

Comparing post-treatment outcomes fo groups treated in a period against a similar group that is never treated (using matching).

Treatment status cannot switch (once treated, stay treated for the rest of the panel)

Package:

did

-

(L. Sun and Abraham 2021): a specialization of (Callaway and Sant’Anna 2021) in the event-study context.

They include lags and leads in their design

have cohort-specific estimates (similar to group-time estimates in (Callaway and Sant’Anna 2021)

They propose the “interaction-weighted” estimator.

Package:

fixest

-

Different from (Callaway and Sant’Anna 2021) because they allow units to switch in and out of treatment.

Based on matching methods, to have weighted TWFE

Package:

wfeandPanelMatch

-

(Gardner 2022): two-stage DiD

did2s

In cases with an unaffected unit (i.e., never-treated), using the exposure-adjusted difference-in-differences estimators can recover the average treatment effect (Clément De Chaisemartin and d’Haultfoeuille 2020). However, if you want to see the treatment effect heterogeneity (in cases where the true heterogeneous treatment effects vary by the exposure rate), exposure-adjusted did still fails (L. Sun and Shapiro 2022).

(2020): see below

To be robust against

- time- and unit-varying effects

We can use the reshaped inverse probability weighting (RIPW)- TWFE estimator

With the following assumptions:

SUTVA

Binary treatment: \(\mathbf{W}_i = (W_{i1}, \dots, W_{it})\) where \(\mathbf{W}_i \sim \mathbf{\pi}_i\) generalized propensity score (i.e., each person treatment likelihood follow \(\pi\) regardless of the period)

Then, the unit-time specific effect is \(\tau_{it} = Y_{it}(1) - Y_{it}(0)\)

Then the Doubly Average Treatment Effect (DATE) is

\[ \tau(\xi) = \sum_{T=1}^T \xi_t \left(\frac{1}{n} \sum_{i = 1}^n \tau_{it} \right) \]

where

\(\frac{1}{n} \sum_{i = 1}^n \tau_{it}\) is the unweighted effect of treatment across units (i.e., time-specific ATE).

\(\xi = (\xi_1, \dots, \xi_t)\) are user-specific weights for each time period.

This estimand is called DATE because it’s weighted (averaged) across both time and units.

A special case of DATE is when both time and unit-weights are equal

\[ \tau_{eq} = \frac{1}{nT} \sum_{t=1}^T \sum_{i = 1}^n \tau_{it} \]

Borrowing the idea of inverse propensity-weighted least squares estimator in the cross-sectional case that we reweight the objective function via the treatment assignment mechanism:

\[ \hat{\tau} \triangleq \arg \min_{\tau} \sum_{i = 1}^n (Y_i -\mu - W_i \tau)^2 \frac{1}{\pi_i (W_i)} \]

where

the first term is the least squares objective

the second term is the propensity score

In the panel data case, the IPW estimator will be

\[ \hat{\tau}_{IPW} \triangleq \arg \min_{\tau} \sum_{i = 1}^n \sum_{t =1}^T (Y_{i t}-\alpha_i - \lambda_t - W_{it} \tau)^2 \frac{1}{\pi_i (W_i)} \]

Then, to have DATE that users can specify the structure of time weight, we use reshaped IPW estimator (2020)

\[ \hat{\tau}_{RIPW} (\Pi) \triangleq \arg \min_{\tau} \sum_{i = 1}^n \sum_{t =1}^T (Y_{i t}-\alpha_i - \lambda_t - W_{it} \tau)^2 \frac{\Pi(W_i)}{\pi_i (W_i)} \]

where it’s a function of a data-independent distribution \(\Pi\) that depends on the support of the treatment path \(\mathbb{S} = \cup_i Supp(W_i)\)

This generalization can transform to

IPW-TWFE estimator when \(\Pi \sim Unif(\mathbb{S})\)

randomized experiment when \(\Pi = \pi_i\)

To choose \(\Pi\), we don’t need to data, we just need possible assignments in your setting.

For most practical problems (DiD, staggered, transient), we have closed form solutions

For generic solver, we can use nonlinear programming (e..g, BFGS algorithm)

As argued in (Imai and Kim 2021) that TWFE is not a non-parametric approach, it can be subjected to incorrect model assumption (i.e., model dependence).

Hence, they advocate for matching methods for time-series cross-sectional data (Imai and Kim 2021)

Use

wfeandPanelMatchto apply their paper.

This package is based on (Somaini and Wolak 2016)

# devtools::install_github("paulosomaini/xtreg2way")

library(xtreg2way)

# output <- xtreg2way(y,

# data.frame(x1, x2),

# iid,

# tid,

# w,

# noise = "1",

# se = "1")

# equilvalently

output <- xtreg2way(l_homicide ~ post,

df,

iid = df$state, # group id

tid = df$year, # time id

# w, # vector of weight

se = "1")

output$betaHat

#> [,1]

#> l_homicide 0.08181162

output$aVarHat

#> [,1]

#> [1,] 0.003396724

# to save time, you can use your structure in the

# last output for a new set of variables

# output2 <- xtreg2way(y, x1, struc=output$struc)Standard errors estimation options

| Set | Estimation |

|---|---|

se = "0" |

Assume homoskedasticity and no within group correlation or serial correlation |

se = "1" (default) |

robust to heteroskadasticity and serial correlation (Arellano 1987) |

se = "2" |

robust to heteroskedasticity, but assumes no correlation within group or serial correlation |

se = "11" |

Aerllano SE with df correction performed by Stata xtreg (Somaini and Wolak 2021) |

Alternatively, you can also do it manually or with the plm package, but you have to be careful with how the SEs are estimated

library(multiwayvcov) # get vcov matrix

library(lmtest) # robust SEs estimation

# manual

output3 <- lm(l_homicide ~ post + factor(state) + factor(year),

data = df)

# get variance-covariance matrix

vcov_tw <- multiwayvcov::cluster.vcov(output3,

cbind(df$state, df$year),

use_white = F,

df_correction = F)

# get coefficients

coeftest(output3, vcov_tw)[2,]

#> Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

#> 0.08181162 0.05671410 1.44252696 0.14979397

# using the plm package

library(plm)

output4 <- plm(l_homicide ~ post,

data = df,

index = c("state", "year"),

model = "within",

effect = "twoways")

# get coefficients

coeftest(output4, vcov = vcovHC, type = "HC1")

#>

#> t test of coefficients:

#>

#> Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

#> post 0.081812 0.057748 1.4167 0.1572As you can see, differences stem from SE estimation, not the coefficient estimate.

26.8 Multiple periods and variation in treatment timing

This is an extension of the DiD framework to settings where you have

more than 2 time periods

different treatment timing

When treatment effects are heterogeneous across time or units, the standard Two-way Fixed-effects is inappropriate.

Notation is consistent with did package (Callaway and Sant’Anna 2021)

\(Y_{it}(0)\) is the potential outcome for unit \(i\)

\(Y_{it}(g)\) is the potential outcome for unit \(i\) in time period \(t\) if it’s treated in period \(g\)

\(Y_{it}\) is the observed outcome for unit \(i\) in time period \(t\)

\[ Y_{it} = \begin{cases} Y_{it} = Y_{it}(0) & \forall i \in \text{never-treated group} \\ Y_{it} = 1\{G_i > t\} Y_{it}(0) + 1\{G_i \le t \}Y_{it}(G_i) & \forall i \in \text{other groups} \end{cases} \]

\(G_i\) is the time period when \(i\) is treated

\(C_i\) is a dummy when \(i\) belongs to the never-treated group

\(D_{it}\) is a dummy for whether \(i\) is treated in period \(t\)

Assumptions:

Staggered treatment adoption: once treated, a unit cannot be untreated (revert)

-

Parallel trends assumptions (conditional on covariates):

-

Based on never-treated units: \(E[Y_t(0)- Y_{t-1}(0)|G= g] = E[Y_t(0) - Y_{t-1}(0)|C=1]\)

- Without treatment, the average potential outcomes for group \(g\) equals the average potential outcomes for the never-treated group (i.e., control group), which means that we have (1) enough data on the never-treated group (2) the control group is similar to the eventually treated group.

-

Based on not-yet treated units: \(E[Y_t(0) - Y_{t-1}(0)|G = g] = E[Y_t(0) - Y_{t-1}(0)|D_s = 0, G \neq g]\)

Not-yet treated units by time \(s\) ( \(s \ge t\)) can be used as comparison groups to calculate the average treatment effects for the group first treated in time \(g\)

Additional assumption: pre-treatment trends across groups (Marcus and Sant’Anna 2021)

-

Random sampling

Irreversibility of treatment (once treated, cannot be untreated)

Overlap (the treatment propensity \(e \in [0,1]\))

Group-Time ATE

- This is the equivalent of the average treatment effect in the standard case (2 groups, 2 periods) under multiple time periods.

\[ ATT(g,t) = E[Y_t(g) - Y_t(0) |G = g] \]

which is the average treatment effect for group \(g\) in period \(t\)

-

Identification: When the parallel trends assumption based on

Never-treated units: \(ATT(g,t) = E[Y_t - Y_{g-1} |G = g] - E[Y_t - Y_{g-1}|C=1] \forall t \ge g\)

Not-yet-treated units: \(ATT(g,t) = E[Y_t - Y_{g-1}|G= g] - E[Y_t - Y_{g-1}|D_t = 0, G \neq g] \forall t \ge g\)

-

Identification: when the parallel trends assumption only holds conditional on covariates and based on

Never-treated units: \(ATT(g,t) = E[Y_t - Y_{g-1} |X, G = g] - E[Y_t - Y_{g-1}|X, C=1] \forall t \ge g\)

Not-yet-treated units: \(ATT(g,t) = E[Y_t - Y_{g-1}|X, G= g] - E[Y_t - Y_{g-1}|X, D_t = 0, G \neq g] \forall t \ge g\)

This is plausible when you have suspected selection bias that can be corrected by using covariates (i.e., very much similar to matching methods to have plausible parallel trends).

Possible parameters of interest are:

- Average treatment effect per group

\[ \theta_S(g) = \frac{1}{\tau - g + 1} \sum_{t = 2}^\tau \mathbb{1} \{ \le t \} ATT(g,t) \]

- Average treatment effect across groups (that were treated) (similar to average treatment effect on the treated in the canonical case)

\[ \theta_S^O := \sum_{g=2}^\tau \theta_S(g) P(G=g) \]

- Average treatment effect dynamics (i.e., average treatment effect for groups that have been exposed to the treatment for \(e\) time periods):

\[ \theta_D(e) := \sum_{g=2}^\tau \mathbb{1} \{g + e \le \tau \}ATT(g,g + e) P(G = g|G + e \le \tau) \]

- Average treatment effect in period \(t\) for all groups that have treated by period \(t\))

\[ \theta_C(t) = \sum_{g=2}^\tau \mathbb{1}\{g \le t\} ATT(g,t) P(G = g|g \le t) \]

- Average treatment effect by calendar time

\[ \theta_C = \frac{1}{\tau-1}\sum_{t=2}^\tau \theta_C(t) \]

26.9 Staggered Dif-n-dif

See Wing et al. (2024) checklist.

Recommendations by Baker, Larcker, and Wang (2022)

TWFE DiD regressions are suitable for single treatment periods or when treatment effects are homogeneous, provided there’s a solid rationale for effect homogeneity.

For TWFE staggered DiD, researchers should evaluate bias risks, plot treatment timings to check for variations, and use decompositions like Goodman-Bacon (2021) when possible. If decompositions aren’t feasible (e.g., unbalanced panel), the percentage of never-treated units can indicate bias severity. Expected treatment effect variability should also be discussed.

In TWFE staggered DiD event studies, avoid binning time periods without evidence of uniform effects. Use full relative-time indicators, justify reference periods, and be wary of multicollinearity causing bias.

To address treatment timing and bias concerns, use alternative estimators like stacked regressions, L. Sun and Abraham (2021), Callaway and Sant’Anna (2021), or separate regressions for each event with “clean” controls.

Justify the selection of comparison groups (not-yet treated, last treated, never treated) and ensure the parallel-trends assumption holds, especially when anticipating no effects for certain groups.

Notes:

- When subjects are treated at different point in time (variation in treatment timing across units), we have to use staggered DiD (also known as DiD event study or dynamic DiD).

- For design where a treatment is applied and units are exposed to this treatment at all time afterward, see (Athey and Imbens 2022)

For example, basic design (Stevenson and Wolfers 2006)

\[ \begin{aligned} Y_{it} &= \sum_k \beta_k Treatment_{it}^k + \sum_i \eta_i State_i \\ &+ \sum_t \lambda_t Year_t + Controls_{it} + \epsilon_{it} \end{aligned} \]

where

\(Treatment_{it}^k\) is a series of dummy variables equal to 1 if state \(i\) is treated \(k\) years ago in period \(t\)

SE is usually clustered at the group level (occasionally time level).

To avoid collinearity, the period right before treatment is usually chosen to drop.

The more general form of TWFE (L. Sun and Abraham 2021):

First, define the relative period bin indicator as

\[ D_{it}^l = \mathbf{1}(t - E_i = l) \]

where it’s an indicator function of unit \(i\) being \(l\) periods from its first treatment at time \(t\)

- Static specification

\[ Y_{it} = \alpha_i + \lambda_t + \mu_g \sum_{l \ge0} D_{it}^l + \epsilon_{it} \]

where

\(\alpha_i\) is the the unit FE

\(\lambda_t\) is the time FE

\(\mu_g\) is the coefficient of interest \(g = [0,T)\)

we exclude all periods before first adoption.

- Dynamic specification

\[ Y_{it} = \alpha_i + \lambda_t + \sum_{\substack{l = -K \\ l \neq -1}}^{L} \mu_l D_{it}^l + \epsilon_{it} \]

where we have to exclude some relative periods to avoid multicollinearity problem (e.g., either period right before treatment, or the treatment period).

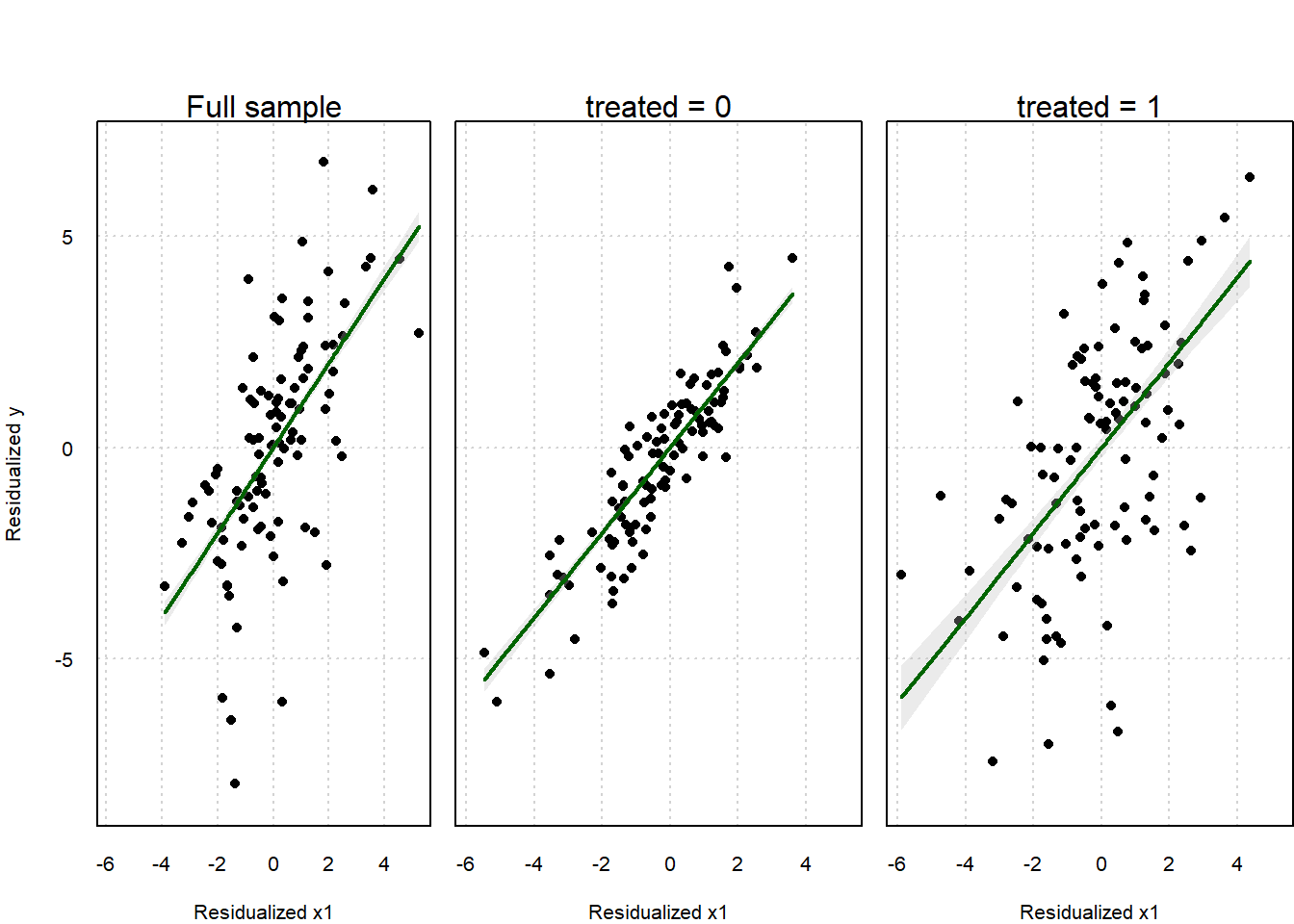

In this setting, we try to show that the treatment and control groups are not statistically different (i.e., the coefficient estimates before treatment are not different from 0) to show pre-treatment parallel trends.

However, this two-way fixed effects design has been criticized by L. Sun and Abraham (2021); Callaway and Sant’Anna (2021); Goodman-Bacon (2021). When researchers include leads and lags of the treatment to see the long-term effects of the treatment, these leads and lags can be biased by effects from other periods, and pre-trends can falsely arise due to treatment effects heterogeneity.

Applying the new proposed method, finance and accounting researchers find that in many cases, the causal estimates turn out to be null (Baker, Larcker, and Wang 2022).

Assumptions of Staggered DID

-

Rollout Exogeneity (i.e., exogeneity of treatment adoption): if the treatment is randomly implemented over time (i.e., unrelated to variables that could also affect our dependent variables)

- Evidence: Regress adoption on pre-treatment variables. And if you find evidence of correlation, include linear trends interacted with pre-treatment variables (Hoynes and Schanzenbach 2009)

- Evidence: (Deshpande and Li 2019, 223)

- Treatment is random: Regress treatment status at the unit level to all pre-treatment observables. If you have some that are predictive of treatment status, you might have to argue why it’s not a worry. At best, you want this.

- Treatment timing is random: Conditional on treatment, regress timing of the treatment on pre-treatment observables. At least, you want this.

No confounding events

-

Exclusion restrictions

No-anticipation assumption: future treatment time do not affect current outcomes

Invariance-to-history assumption: the time a unit under treatment does not affect the outcome (i.e., the time exposed does not matter, just whether exposed or not). This presents causal effect of early or late adoption on the outcome.

And all the assumptions in listed in the Multiple periods and variation in treatment timing

-

Auxiliary assumptions:

Constant treatment effects across units

Constant treatment effect over time

Random sampling

Effect Additivity

Remedies for staggered DiD (Baker, Larcker, and Wang 2022):

-

Each treated cohort is compared to appropriate controls (not-yet-treated, never-treated)

-

(Callaway and Sant’Anna 2021) consistent for average ATT. more complicated but also more flexible than (L. Sun and Abraham 2021)

- (L. Sun and Abraham 2021) (a special case of (Callaway and Sant’Anna 2021))

-

Stacked DID (biased but simple):

26.9.1 Stacked DID

Notations following these slides

\[ Y_{it} = \beta_{FE} D_{it} + A_i + B_t + \epsilon_{it} \]

where

\(A_i\) is the group fixed effects

\(B_t\) is the period fixed effects

Steps

- Choose Event Window

- Enumerate Sub-experiments

- Define Inclusion Criteria

- Stack Data

- Specify Estimating Equation

Event Window

Let

\(\kappa_a\) be the length of the pre-event window

\(\kappa_b\) be the length of the post-event window

By setting a common event window for the analysis, we essentially exclude all those events that do not meet this criteria.

Sub-experiments

Let \(T_1\) be the earliest period in the dataset

\(T_T\) be the last period in the dataset

Then, the collection of all policy adoption periods that are under our event window is

\[ \Omega_A = \{ A_i |T_1 + \kappa_a \le A_i \le T_T - \kappa_b\} \]

where these events exist

at least \(\kappa_a\) periods after the earliest period

at least \(\kappa_b\) periods before the last period

Let \(d = 1, \dots, D\) be the index column of the sub-experiments in \(\Omega_A\)

and \(\omega_d\) be the event date of the d-th sub-experiment (e.g., \(\omega_1\) = adoption date of the 1st experiment)

Inclusion Criteria

- Valid treated Units

Within sub-experiment \(d\), all treated units have the same adoption date

This makes sure a unit can only serve as a treated unit in only 1 sub-experiment

- Clean controls

Only units satisfying \(A_i >\omega_d + \kappa_b\) are included as controls in sub-experiment d

-

This ensures controls are only

never treated units

units that are treated in far future

But a unit can be control unit in multiple sub-experiments (need to correct SE)

- Valid Time Periods

All observations within sub-experiment d are from time periods within the sub-experiment’s event window

This ensures in sub-experiment d, only observations satisfying \(\omega_d - \kappa_a \le t \le \omega_d + \kappa_b\) are included

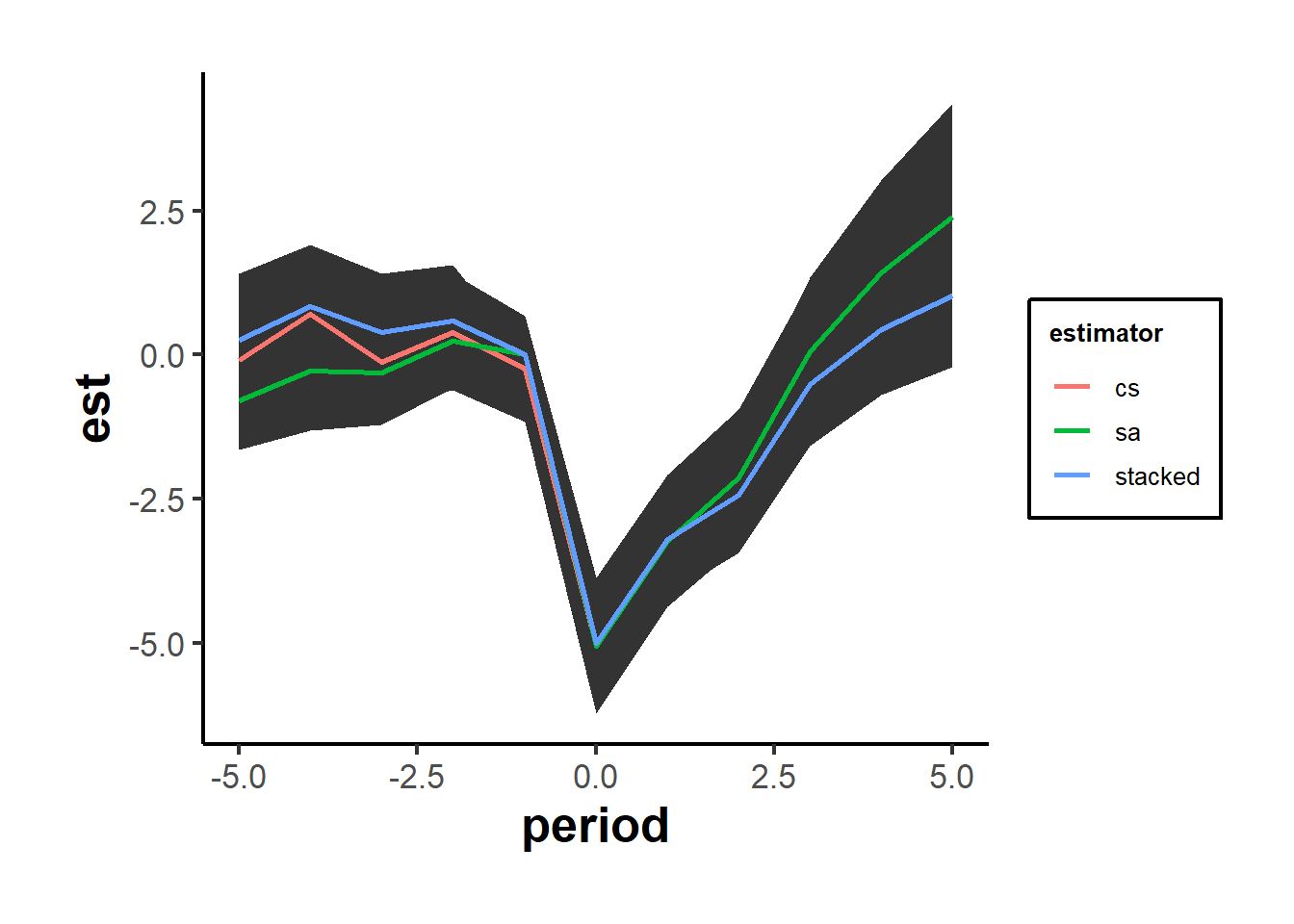

library(did)

library(tidyverse)

library(fixest)

data(base_stagg)

# first make the stacked datasets

# get the treatment cohorts

cohorts <- base_stagg %>%

select(year_treated) %>%

# exclude never-treated group

filter(year_treated != 10000) %>%

unique() %>%

pull()

# make formula to create the sub-datasets

getdata <- function(j, window) {

#keep what we need

base_stagg %>%

# keep treated units and all units not treated within -5 to 5

# keep treated units and all units not treated within -window to window

filter(year_treated == j | year_treated > j + window) %>%

# keep just year -window to window

filter(year >= j - window & year <= j + window) %>%

# create an indicator for the dataset

mutate(df = j)

}

# get data stacked

stacked_data <- map_df(cohorts, ~ getdata(., window = 5)) %>%

mutate(rel_year = if_else(df == year_treated, time_to_treatment, NA_real_)) %>%

fastDummies::dummy_cols("rel_year", ignore_na = TRUE) %>%

mutate(across(starts_with("rel_year_"), ~ replace_na(., 0)))

# get stacked value

stacked <-

feols(

y ~ `rel_year_-5` + `rel_year_-4` + `rel_year_-3` +

`rel_year_-2` + rel_year_0 + rel_year_1 + rel_year_2 + rel_year_3 +

rel_year_4 + rel_year_5 |

id ^ df + year ^ df,

data = stacked_data

)$coefficients

stacked_se = feols(

y ~ `rel_year_-5` + `rel_year_-4` + `rel_year_-3` +

`rel_year_-2` + rel_year_0 + rel_year_1 + rel_year_2 + rel_year_3 +

rel_year_4 + rel_year_5 |

id ^ df + year ^ df,

data = stacked_data

)$se

# add in 0 for omitted -1

stacked <- c(stacked[1:4], 0, stacked[5:10])

stacked_se <- c(stacked_se[1:4], 0, stacked_se[5:10])

cs_out <- att_gt(

yname = "y",

data = base_stagg,

gname = "year_treated",

idname = "id",

# xformla = "~x1",

tname = "year"

)

cs <-

aggte(

cs_out,

type = "dynamic",

min_e = -5,

max_e = 5,

bstrap = FALSE,

cband = FALSE

)

res_sa20 = feols(y ~ sunab(year_treated, year) |

id + year, base_stagg)

sa = tidy(res_sa20)[5:14, ] %>% pull(estimate)

sa = c(sa[1:4], 0, sa[5:10])

sa_se = tidy(res_sa20)[6:15, ] %>% pull(std.error)

sa_se = c(sa_se[1:4], 0, sa_se[5:10])

compare_df_est = data.frame(

period = -5:5,

cs = cs$att.egt,

sa = sa,

stacked = stacked

)

compare_df_se = data.frame(

period = -5:5,

cs = cs$se.egt,

sa = sa_se,

stacked = stacked_se

)

compare_df_longer <- compare_df_est %>%

pivot_longer(!period, names_to = "estimator", values_to = "est") %>%

full_join(compare_df_se %>%

pivot_longer(!period, names_to = "estimator", values_to = "se")) %>%

mutate(upper = est + 1.96 * se,

lower = est - 1.96 * se)

ggplot(compare_df_longer) +

geom_ribbon(aes(

x = period,

ymin = lower,

ymax = upper,

group = estimator

)) +

geom_line(aes(

x = period,

y = est,

group = estimator,

col = estimator

),

linewidth = 1) +

causalverse::ama_theme()

Stack Data

Estimating Equation

\[ Y_{itd} = \beta_0 + \beta_1 T_{id} + \beta_2 P_{td} + \beta_3 (T_{id} \times P_{td}) + \epsilon_{itd} \]

where

\(T_{id}\) = 1 if unit \(i\) is treated in sub-experiment \(d\), 0 if control

\(P_{td}\) = 1 if it’s the period after the treatment in sub-experiment \(d\)

Equivalently,

\[ Y_{itd} = \beta_3 (T_{id} \times P_{td}) + \theta_{id} + \gamma_{td} + \epsilon_{itd} \]

\(\beta_3\) averages all the time-varying effects into a single number (can’t see the time-varying effects)

Stacked Event Study

Let \(YSE_{td} = t - \omega_d\) be the “time since event” variable in sub-experiment \(d\)

Then, \(YSE_{td} = -\kappa_a, \dots, 0, \dots, \kappa_b\) in every sub-experiment

In each sub-experiment, we can fit

\[ Y_{it}^d = \sum_{j = -\kappa_a}^{\kappa_b} \beta_j^d \times 1(TSE_{td} = j) + \sum_{m = -\kappa_a}^{\kappa_b} \delta_j^d (T_{id} \times 1 (TSE_{td} = j)) + \theta_i^d + \epsilon_{it}^d \]

- Different set of event study coefficients in each sub-experiment

\[ Y_{itd} = \sum_{j = -\kappa_a}^{\kappa_b} \beta_j \times 1(TSE_{td} = j) + \sum_{m = -\kappa_a}^{\kappa_b} \delta_j (T_{id} \times 1 (TSE_{td} = j)) + \theta_{id} + \epsilon_{itd} \]

Clustering

Clustered at the unit x sub-experiment level (Cengiz et al. 2019)

Clustered at the unit level (Deshpande and Li 2019)

26.9.2 Goodman-Bacon Decomposition

Paper: (Goodman-Bacon 2021)

For an excellent explanation slides by the author, see

Takeaways:

A pairwise DID (\(\tau\)) gets more weight if the change is close to the middle of the study window

A pairwise DID (\(\tau\)) gets more weight if it includes more observations.

Code from bacondecomp vignette

library(bacondecomp)

library(tidyverse)

data("castle")

castle <- bacondecomp::castle %>%

dplyr::select("l_homicide", "post", "state", "year")

head(castle)

#> l_homicide post state year

#> 1 2.027356 0 Alabama 2000

#> 2 2.164867 0 Alabama 2001

#> 3 1.936334 0 Alabama 2002

#> 4 1.919567 0 Alabama 2003

#> 5 1.749841 0 Alabama 2004

#> 6 2.130440 0 Alabama 2005

df_bacon <- bacon(

l_homicide ~ post,

data = castle,

id_var = "state",

time_var = "year"

)

#> type weight avg_est

#> 1 Earlier vs Later Treated 0.05976 -0.00554

#> 2 Later vs Earlier Treated 0.03190 0.07032

#> 3 Treated vs Untreated 0.90834 0.08796

# weighted average of the decomposition

sum(df_bacon$estimate * df_bacon$weight)

#> [1] 0.08181162Two-way Fixed effect estimate

library(broom)

fit_tw <- lm(l_homicide ~ post + factor(state) + factor(year),

data = bacondecomp::castle)

head(tidy(fit_tw))

#> # A tibble: 6 × 5

#> term estimate std.error statistic p.value

#> <chr> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

#> 1 (Intercept) 1.95 0.0624 31.2 2.84e-118

#> 2 post 0.0818 0.0317 2.58 1.02e- 2

#> 3 factor(state)Alaska -0.373 0.0797 -4.68 3.77e- 6

#> 4 factor(state)Arizona 0.0158 0.0797 0.198 8.43e- 1

#> 5 factor(state)Arkansas -0.118 0.0810 -1.46 1.44e- 1

#> 6 factor(state)California -0.108 0.0810 -1.34 1.82e- 1Hence, naive TWFE fixed effect equals the weighted average of the Bacon decomposition (= 0.08).

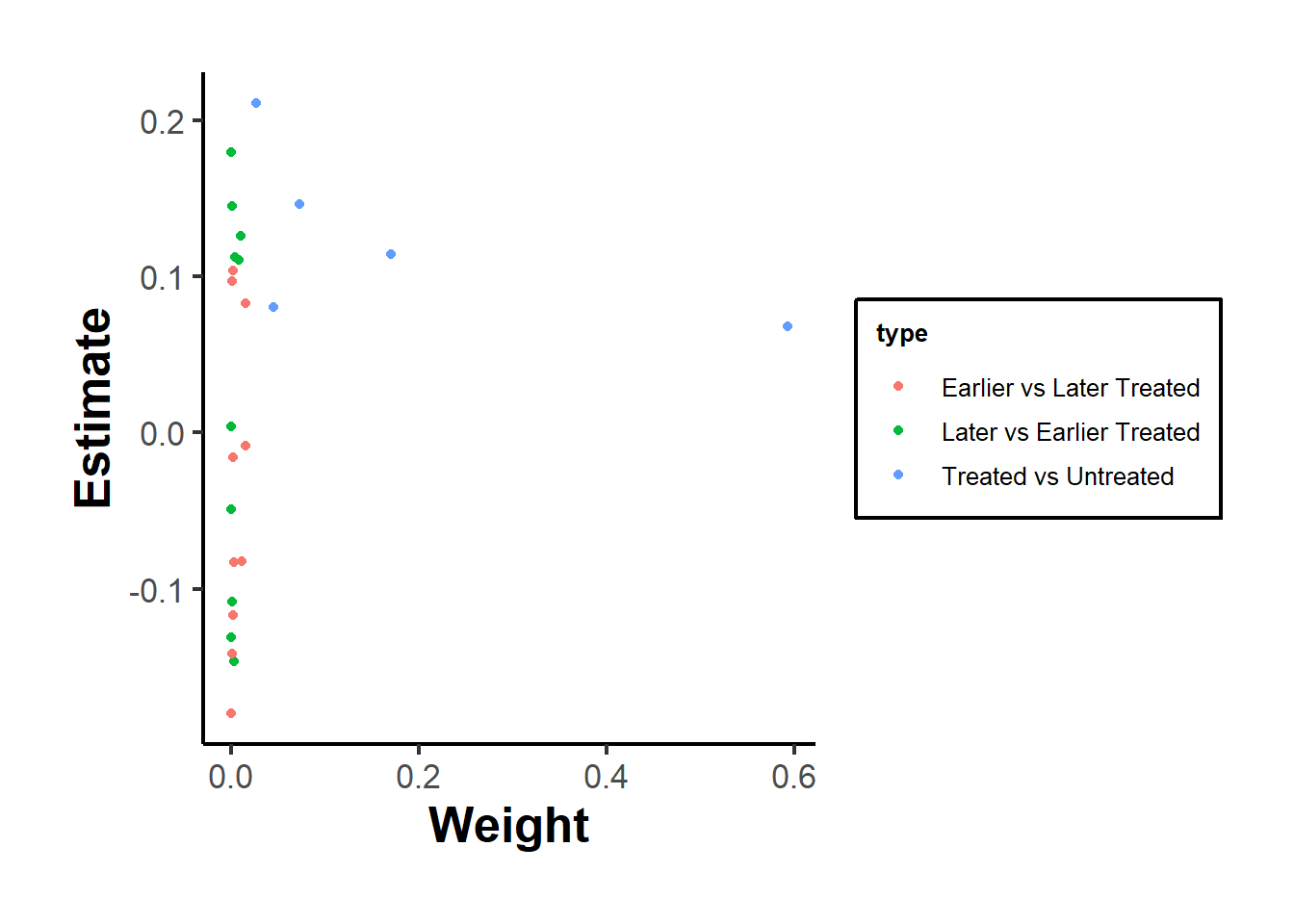

library(ggplot2)

ggplot(df_bacon) +

aes(

x = weight,

y = estimate,

# shape = factor(type),

color = type

) +

labs(x = "Weight", y = "Estimate", shape = "Type") +

geom_point() +

causalverse::ama_theme()

With time-varying controls that can identify variation within-treatment timing group, the”early vs. late” and “late vs. early” estimates collapse to just one estimate (i.e., both treated).

26.9.3 DID with in and out treatment condition

26.9.3.1 Panel Match

Imai and Kim (2021)

This case generalizes the staggered adoption setting, allowing units to vary in treatment over time. For \(N\) units across \(T\) time periods (with potentially unbalanced panels), let \(X_{it}\) represent treatment and \(Y_{it}\) the outcome for unit \(i\) at time \(t\). We use the two-way linear fixed effects model:

\[ Y_{it} = \alpha_i + \gamma_t + \beta X_{it} + \epsilon_{it} \]

for \(i = 1, \dots, N\) and \(t = 1, \dots, T\). Here, \(\alpha_i\) and \(\gamma_t\) are unit and time fixed effects. They capture time-invariant unit-specific and unit-invariant time-specific unobserved confounders, respectively. We can express these as \(\alpha_i = h(\mathbf{U}_i)\) and \(\gamma_t = f(\mathbf{V}_t)\), with \(\mathbf{U}_i\) and \(\mathbf{V}_t\) being the confounders. The model doesn’t assume a specific form for \(h(.)\) and \(f(.)\), but that they’re additive and separable given binary treatment.

The least squares estimate of \(\beta\) leverages the covariance in outcome and treatment (Imai and Kim 2021, 406). Specifically, it uses the within-unit and within-time variations. Many researchers prefer the two fixed effects (2FE) estimator because it adjusts for both types of unobserved confounders without specific functional-form assumptions, but this is wrong (Imai and Kim 2019). We do need functional-form assumption (i.e., linearity assumption) for the 2FE to work (Imai and Kim 2021, 406)

-

Two-Way Matching Estimator:

It can lead to mismatches; units with the same treatment status get matched when estimating counterfactual outcomes.

Observations need to be matched with opposite treatment status for correct causal effects estimation.

Mismatches can cause attenuation bias.

The 2FE estimator adjusts for this bias using the factor \(K\), which represents the net proportion of proper matches between observations with opposite treatment status.

-

Weighting in 2FE:

Observation \((i,t)\) is weighted based on how often it acts as a control unit.

The weighted 2FE estimator still has mismatches, but fewer than the standard 2FE estimator.

Adjustments are made based on observations that neither belong to the same unit nor the same time period as the matched observation.

This means there are challenges in adjusting for unit-specific and time-specific unobserved confounders under the two-way fixed effect framework.

-

Equivalence & Assumptions:

Equivalence between the 2FE estimator and the DID estimator is dependent on the linearity assumption.

The multi-period DiD estimator is described as an average of two-time-period, two-group DiD estimators applied during changes from control to treatment.

-

Comparison with DiD:

In simple settings (two time periods, treatment given to one group in the second period), the standard nonparametric DiD estimator equals the 2FE estimator.

This doesn’t hold in multi-period DiD designs where units change treatment status multiple times at different intervals.

Contrary to popular belief, the unweighted 2FE estimator isn’t generally equivalent to the multi-period DiD estimator.

While the multi-period DiD can be equivalent to the weighted 2FE, some control observations may have negative regression weights.

-

Conclusion:

- Justifying the 2FE estimator as the DID estimator isn’t warranted without imposing the linearity assumption.

Application (Imai, Kim, and Wang 2021)

-

Matching Methods:

Enhance the validity of causal inference.

Reduce model dependence and provide intuitive diagnostics (Ho et al. 2007)

Rarely utilized in analyzing time series cross-sectional data.

The proposed matching estimators are more robust than the standard two-way fixed effects estimator, which can be biased if mis-specified

Better than synthetic controls (e.g., (Xu 2017)) because it needs less data to achieve good performance and and adapt the the context of unit switching treatment status multiple times.

-

Notes:

- Potential carryover effects (treatment may have a long-term effect), leading to post-treatment bias.

-

Proposed Approach:

Treated observations are matched with control observations from other units in the same time period with the same treatment history up to a specified number of lags.

Standard matching and weighting techniques are employed to further refine the matched set.

Apply a DiD estimator to adjust for time trend.

The goal is to have treated and matched control observations with similar covariate values.

-

Assessment:

- The quality of matches is evaluated through covariate balancing.

-

Estimation:

- Both short-term and long-term average treatment effects on the treated (ATT) are estimated.

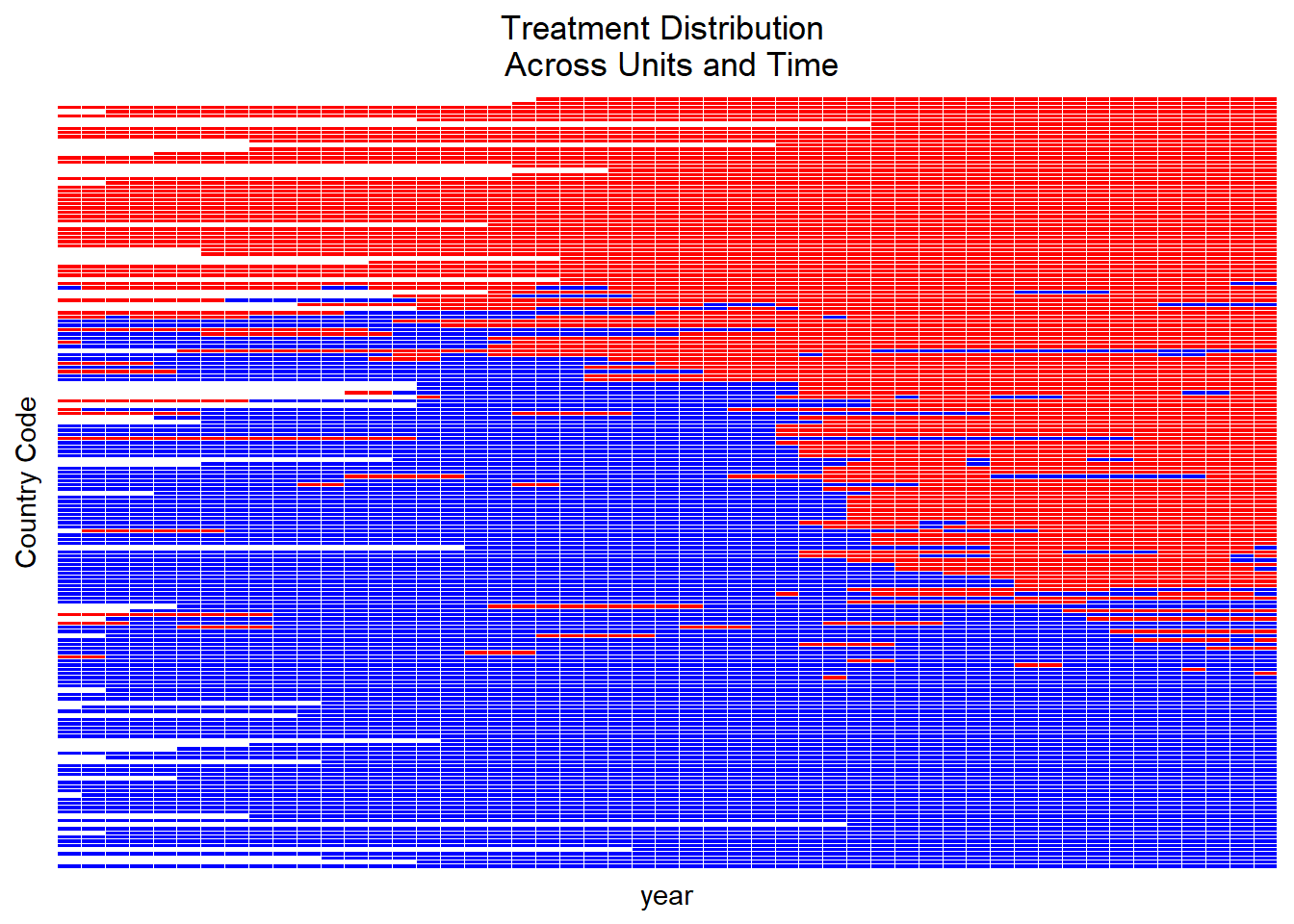

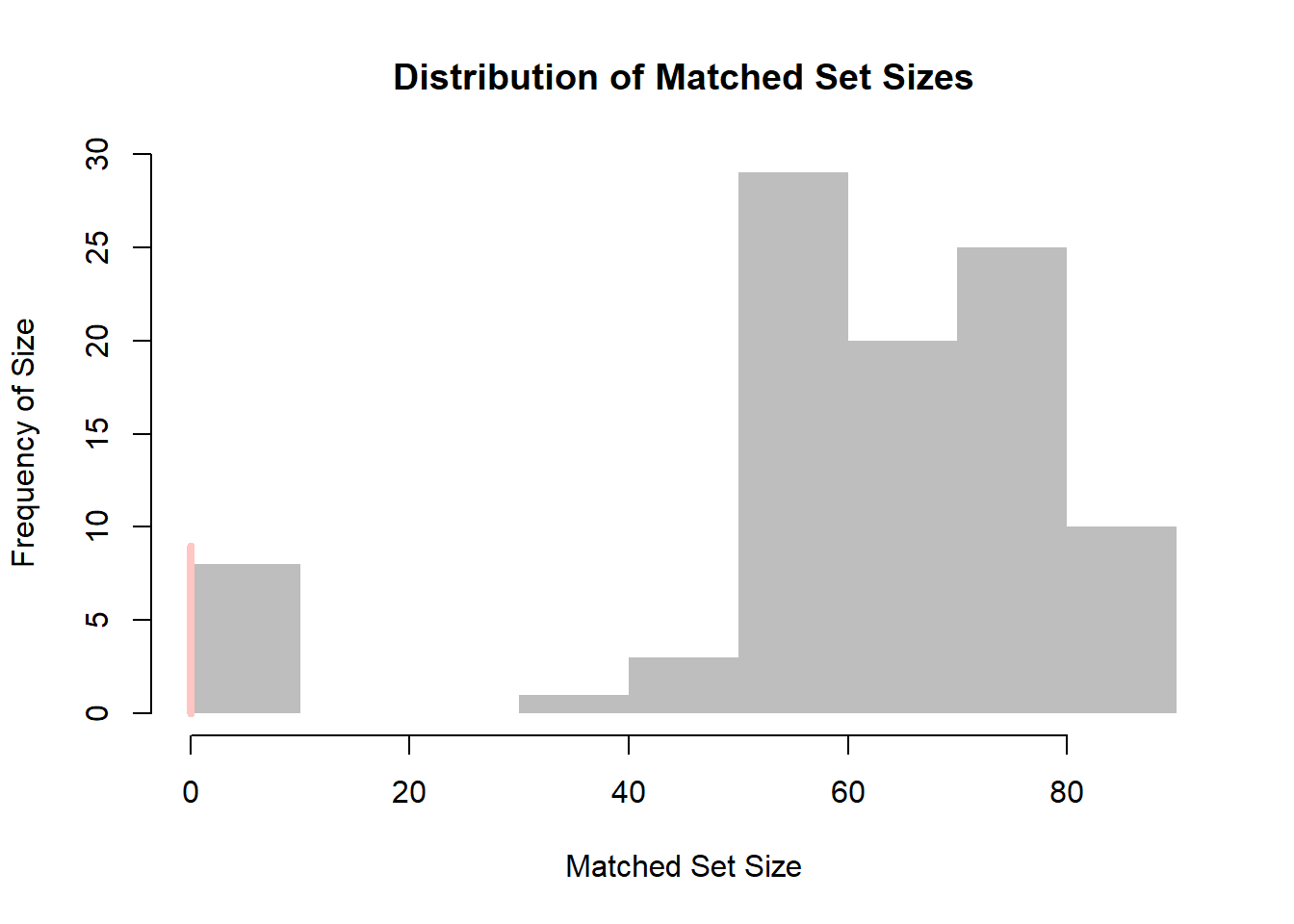

library(PanelMatch)Treatment Variation plot

Visualize the variation of the treatment across space and time

Aids in discerning whether the treatment fluctuates adequately over time and units or if the variation is primarily clustered in a subset of data.

DisplayTreatment(

unit.id = "wbcode2",

time.id = "year",

legend.position = "none",

xlab = "year",

ylab = "Country Code",

treatment = "dem",

hide.x.tick.label = TRUE, hide.y.tick.label = TRUE,

# dense.plot = TRUE,

data = dem

)

- Select \(F\) (i.e., the number of leads - time periods after treatment). Driven by what authors are interested in estimating:

\(F = 0\) is the contemporaneous effect (short-term effect)

\(F = n\) is the the treatment effect on the outcome two time periods after the treatment. (cumulative or long-term effect)

- Select \(L\) (number of lags to adjust).

Driven by the identification assumption.

Balances bias-variance tradeoff.

Higher \(L\) values increase credibility but reduce efficiency by limiting potential matches.

Model assumption:

No spillover effect assumed.

Carryover effect allowed up to \(L\) periods.

Potential outcome for a unit depends neither on others’ treatment status nor on its past treatment after \(L\) periods.

After defining causal quantity with parameters \(L\) and \(F\).

- Focus on the average treatment effect of treatment status change.

- \(\delta(F,L)\) is the average causal effect of treatment change (ATT), \(F\) periods post-treatment, considering treatment history up to \(L\) periods.

- Causal quantity considers potential future treatment reversals, meaning treatment could revert to control before outcome measurement.

Also possible to estimate the average treatment effect of treatment reversal on the reversed (ART).

Choose \(L,F\) based on specific needs.

-

A large \(L\) value:

Increases the credibility of the limited carryover effect assumption.

Allows more past treatments (up to \(t−L\)) to influence the outcome \(Y_{i,t+F}\).

Might reduce the number of matches and lead to less precise estimates.

-

Selecting an appropriate number of lags

Researchers should base this choice on substantive knowledge.

Sensitivity of empirical results to this choice should be examined.

-

The choice of \(F\) should be:

Substantively motivated.

Decides whether the interest lies in short-term or long-term causal effects.

A large \(F\) value can complicate causal effect interpretation, especially if many units switch treatment status during the \(F\) lead time period.

Identification Assumption

Parallel trend assumption conditioned on treatment, outcome (excluding immediate lag), and covariate histories.

Doesn’t require strong unconfoundedness assumption.

Cannot account for unobserved time-varying confounders.

-

Essential to examine outcome time trends.

- Check if they’re parallel between treated and matched control units using pre-treatment data

-

Constructing the Matched Sets:

For each treated observation, create matched control units with identical treatment history from \(t−L\) to \(t−1\).

Matching based on treatment history helps control for carryover effects.

Past treatments often act as major confounders, but this method can correct for it.

Exact matching on time period adjusts for time-specific unobserved confounders.

Unlike staggered adoption methods, units can change treatment status multiple times.

Matched set allows treatment switching in and out of treatment

-

Refining the Matched Sets:

Initially, matched sets adjust only for treatment history.

Parallel trend assumption requires adjustments for other confounders like past outcomes and covariates.

-

Matching methods:

Match each treated observation with up to \(J\) control units.

Distance measures like Mahalanobis distance or propensity score can be used.

Match based on estimated propensity score, considering pretreatment covariates.

Refined matched set selects most similar control units based on observed confounders.

-

Weighting methods:

Assign weight to each control unit in a matched set.

Weights prioritize more similar units.

Inverse propensity score weighting method can be applied.

Weighting is a more generalized method than matching.

The Difference-in-Differences Estimator:

Using refined matched sets, the ATT (Average Treatment Effect on the Treated) of policy change is estimated.

For each treated observation, estimate the counterfactual outcome using the weighted average of control units in the refined set.

The DiD estimate of the ATT is computed for each treated observation, then averaged across all such observations.

-

For noncontemporaneous treatment effects where \(F > 0\):

The ATT doesn’t specify future treatment sequence.

Matched control units might have units receiving treatment between time \(t\) and \(t + F\).

Some treated units could return to control conditions between these times.

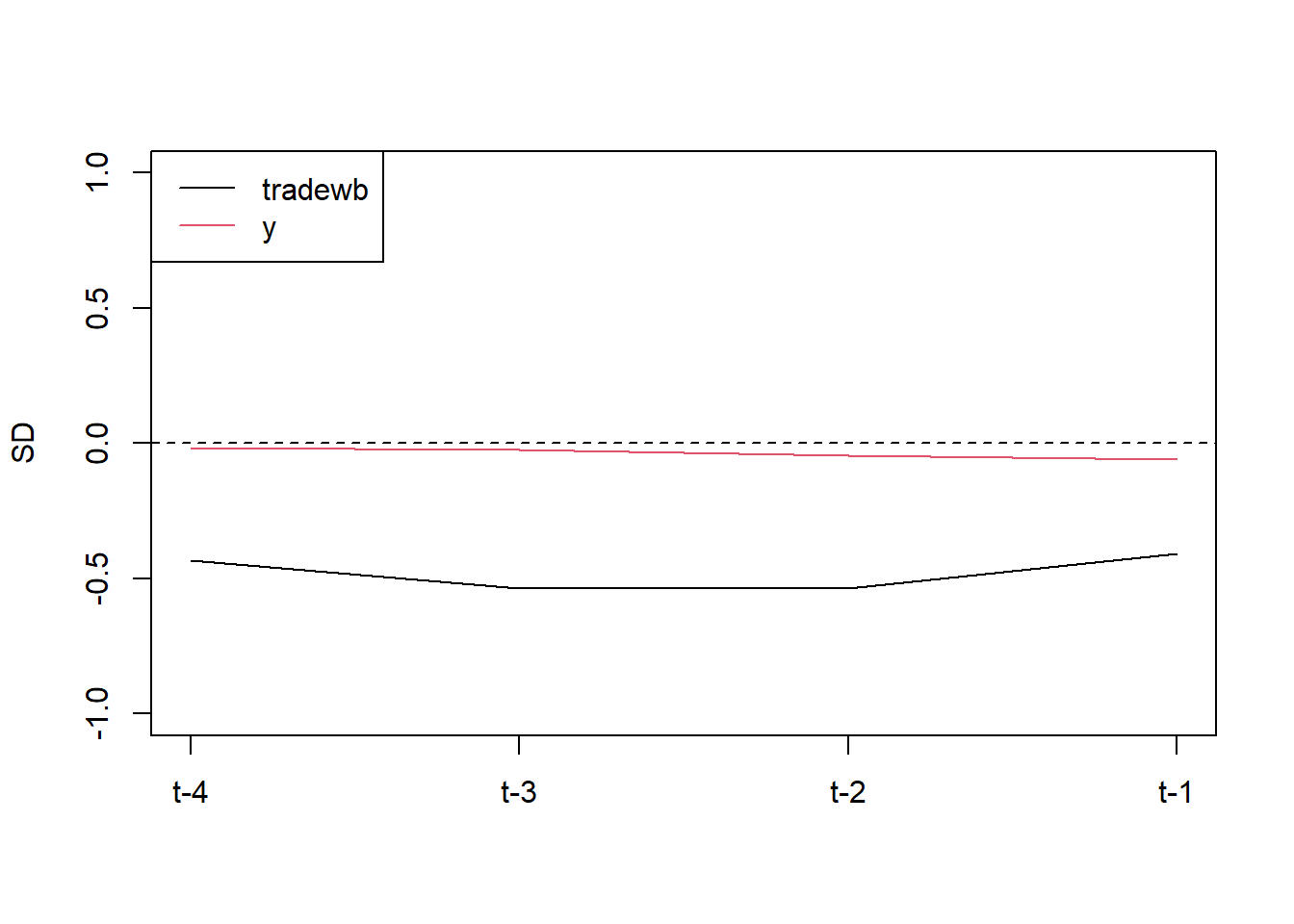

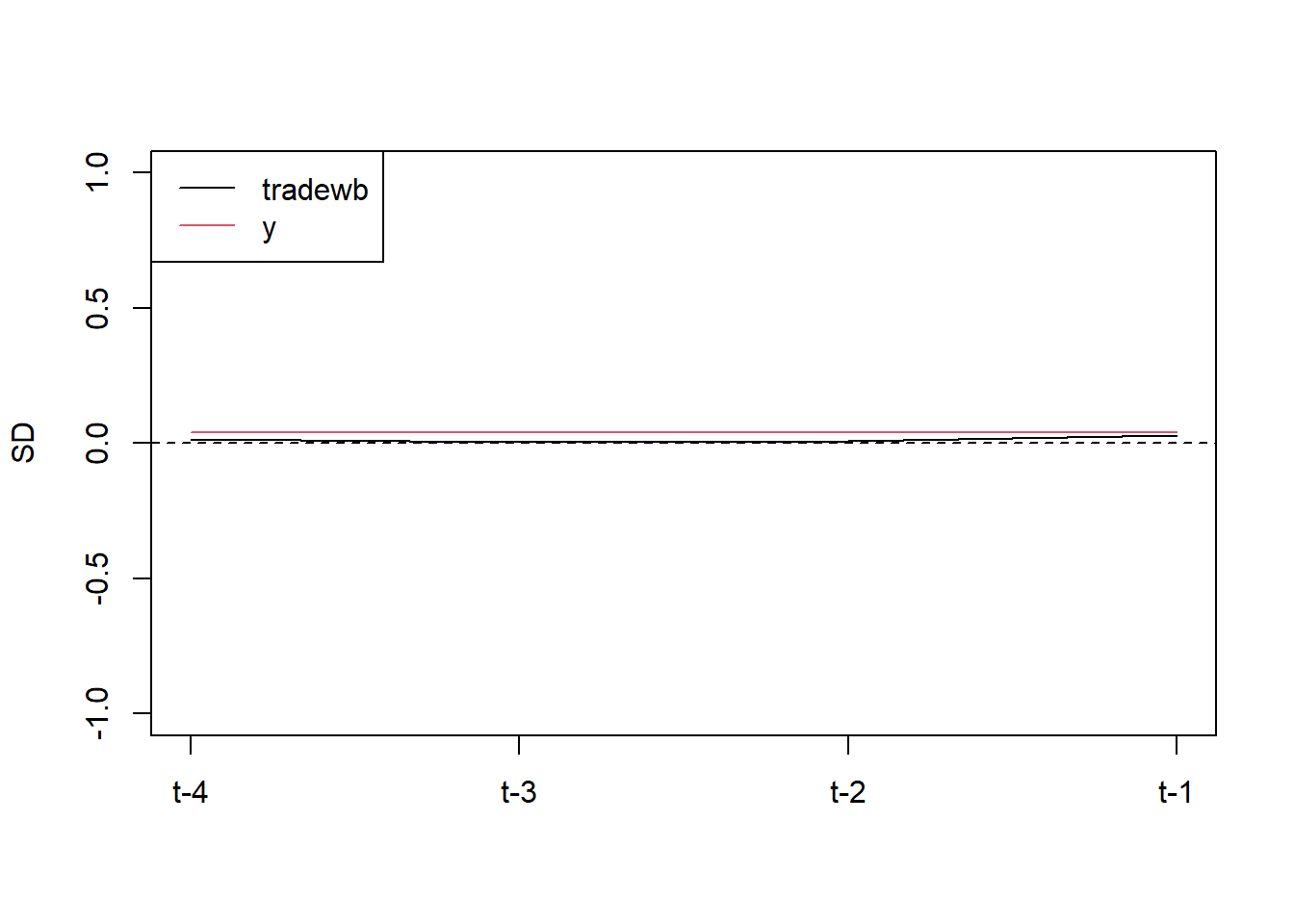

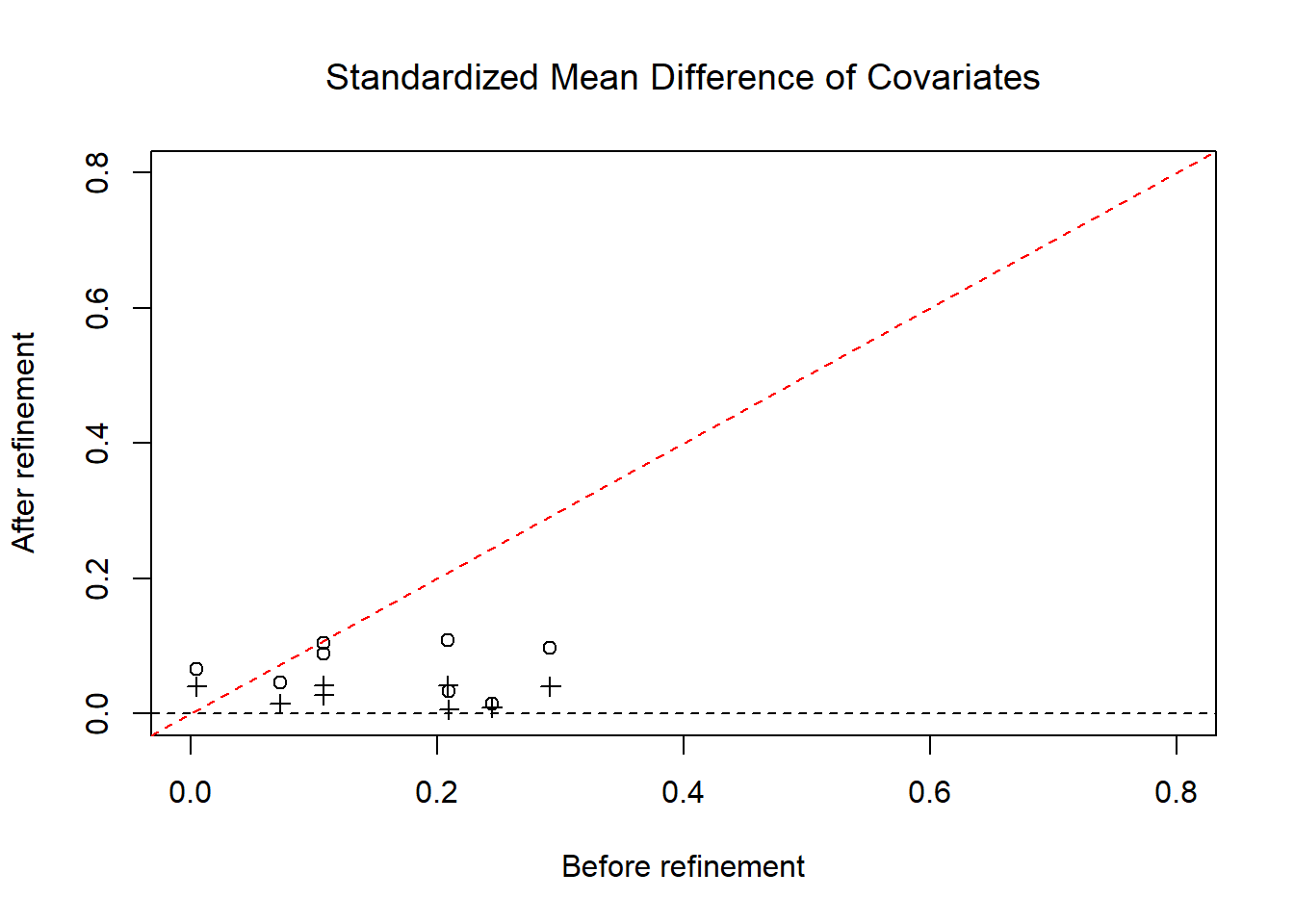

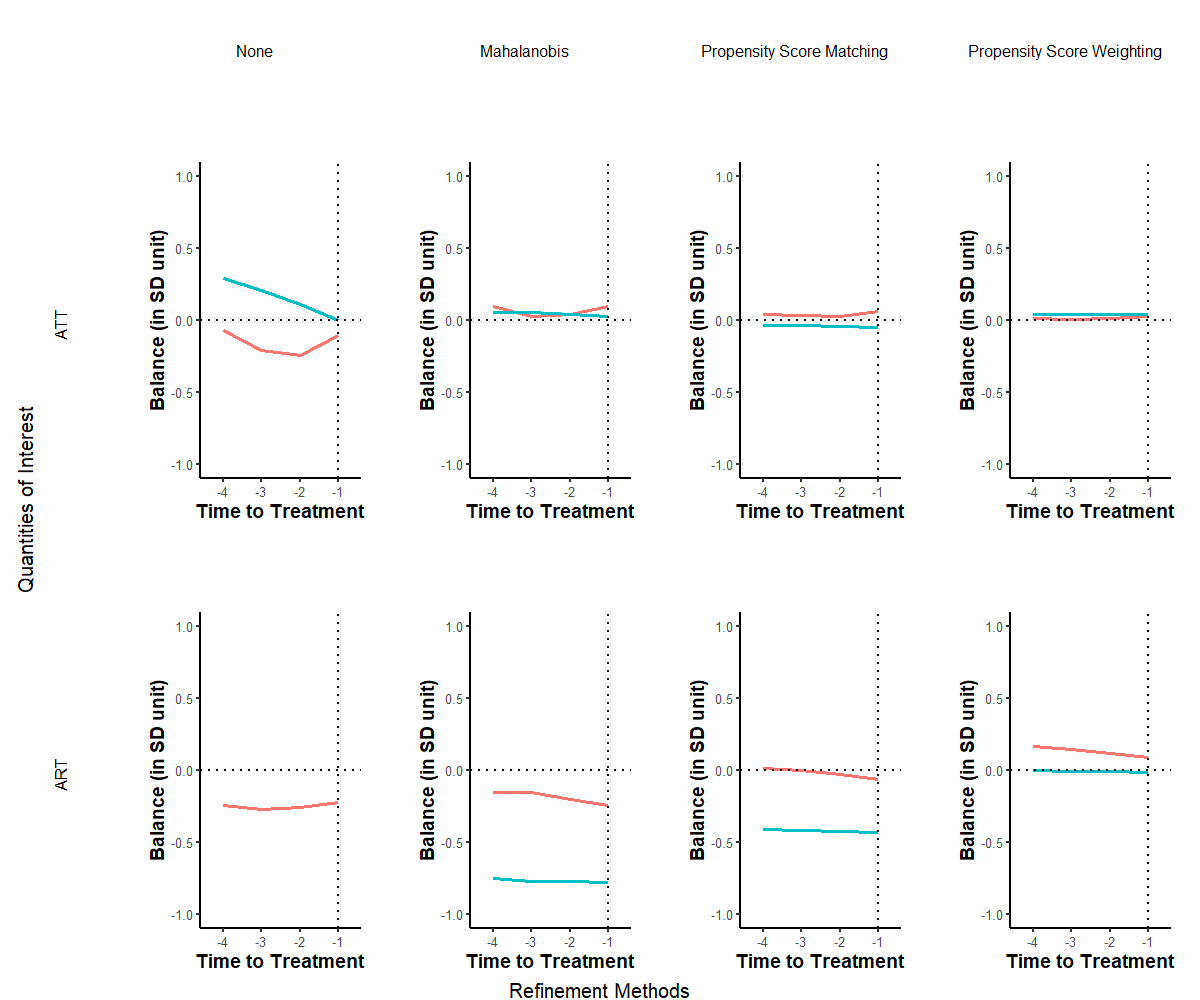

Checking Covariate Balance:

The proposed methodology offers the advantage of checking covariate balance between treated and matched control observations.

This check helps to see if treated and matched control observations are comparable with respect to observed confounders.

Once matched sets are refined, covariate balance examination becomes straightforward.

Examine the mean difference of each covariate between a treated observation and its matched controls for each pretreatment time period.

Standardize this difference using the standard deviation of each covariate across all treated observations in the dataset.

Aggregate this covariate balance measure across all treated observations for each covariate and pretreatment time period.

-

Examine balance for lagged outcome variables over multiple pretreatment periods and time-varying covariates.

- This helps evaluate the validity of the parallel trend assumption underlying the proposed DiD estimator.

Relations with Linear Fixed Effects Regression Estimators:

-

The standard DiD estimator is equivalent to the linear two-way fixed effects regression estimator when:

Only two time periods exist.

Treatment is given to some units exclusively in the second period.

-

This equivalence doesn’t extend to multiperiod DiD designs, where:

More than two time periods are considered.

Units might receive treatment multiple times.

Despite this, many researchers relate the use of the two-way fixed effects estimator to the DiD design.

Standard Error Calculation:

-

Approach:

Condition on the weights implied by the matching process.

These weights denote how often an observation is utilized in matching (G. W. Imbens and Rubin 2015)

-

Context:

Analogous to the conditional variance seen in regression models.

Resulting standard errors don’t factor in uncertainties around the matching procedure.

They can be viewed as a measure of uncertainty conditional upon the matching process (Ho et al. 2007).

Key Findings:

Even in conditions favoring OLS, the proposed matching estimator displayed higher robustness to omitted relevant lags than the linear regression model with fixed effects.

The robustness offered by matching came at a cost - reduced statistical power.

This emphasizes the classic statistical tradeoff between bias (where matching has an advantage) and variance (where regression models might be more efficient).

Data Requirements

-

The treatment variable is binary:

0 signifies “assignment” to control.

1 signifies assignment to treatment.

Variables identifying units in the data must be: Numeric or integer.

Variables identifying time periods should be: Consecutive numeric/integer data.

Data format requirement: Must be provided as a standard

data.frameobject.

Basic functions:

Utilize treatment histories to create matching sets of treated and control units.

-

Refine these matched sets by determining weights for each control unit in the set.

- Units with higher weights have a larger influence during estimations.

Matching on Treatment History:

Goal is to match units transitioning from untreated to treated status with control units that have similar past treatment histories.

-

Setting the Quantity of Interest (

qoi =)attaverage treatment effect on treated unitsatcaverage treatment effect of treatment on the control unitsartaverage effect of treatment reversal for units that experience treatment reversalateaverage treatment effect

library(PanelMatch)

# All examples follow the package's vignette

# Create the matched sets

PM.results.none <-

PanelMatch(

lag = 4,

time.id = "year",

unit.id = "wbcode2",

treatment = "dem",

refinement.method = "none",

data = dem,

match.missing = TRUE,

size.match = 5,

qoi = "att",

outcome.var = "y",

lead = 0:4,

forbid.treatment.reversal = FALSE,

use.diagonal.variance.matrix = TRUE

)

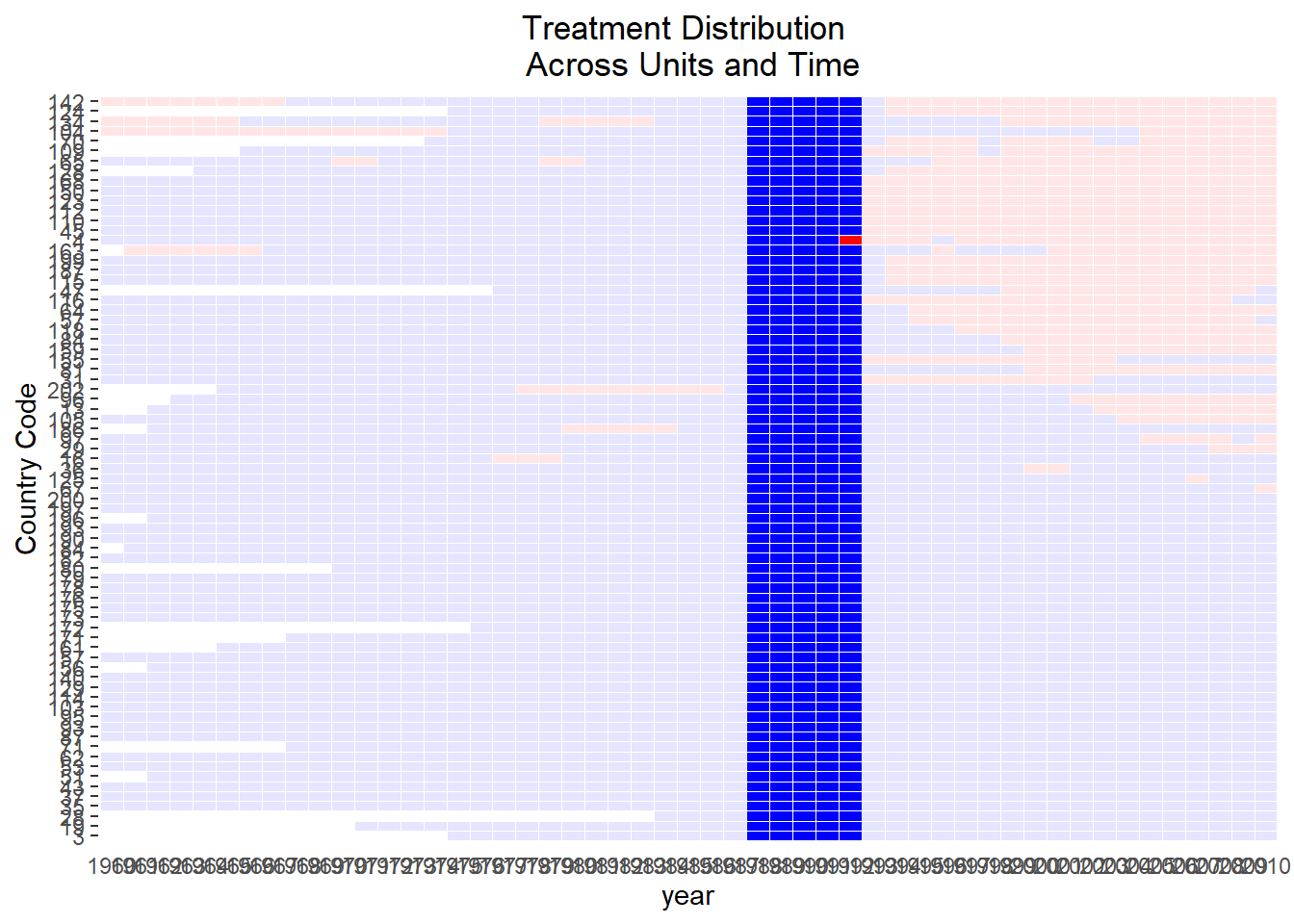

# visualize the treated unit and matched controls

DisplayTreatment(

unit.id = "wbcode2",

time.id = "year",

legend.position = "none",

xlab = "year",

ylab = "Country Code",

treatment = "dem",

data = dem,

matched.set = PM.results.none$att[1],

# highlight the particular set

show.set.only = TRUE

)

Control units and the treated unit have identical treatment histories over the lag window (1988-1991)

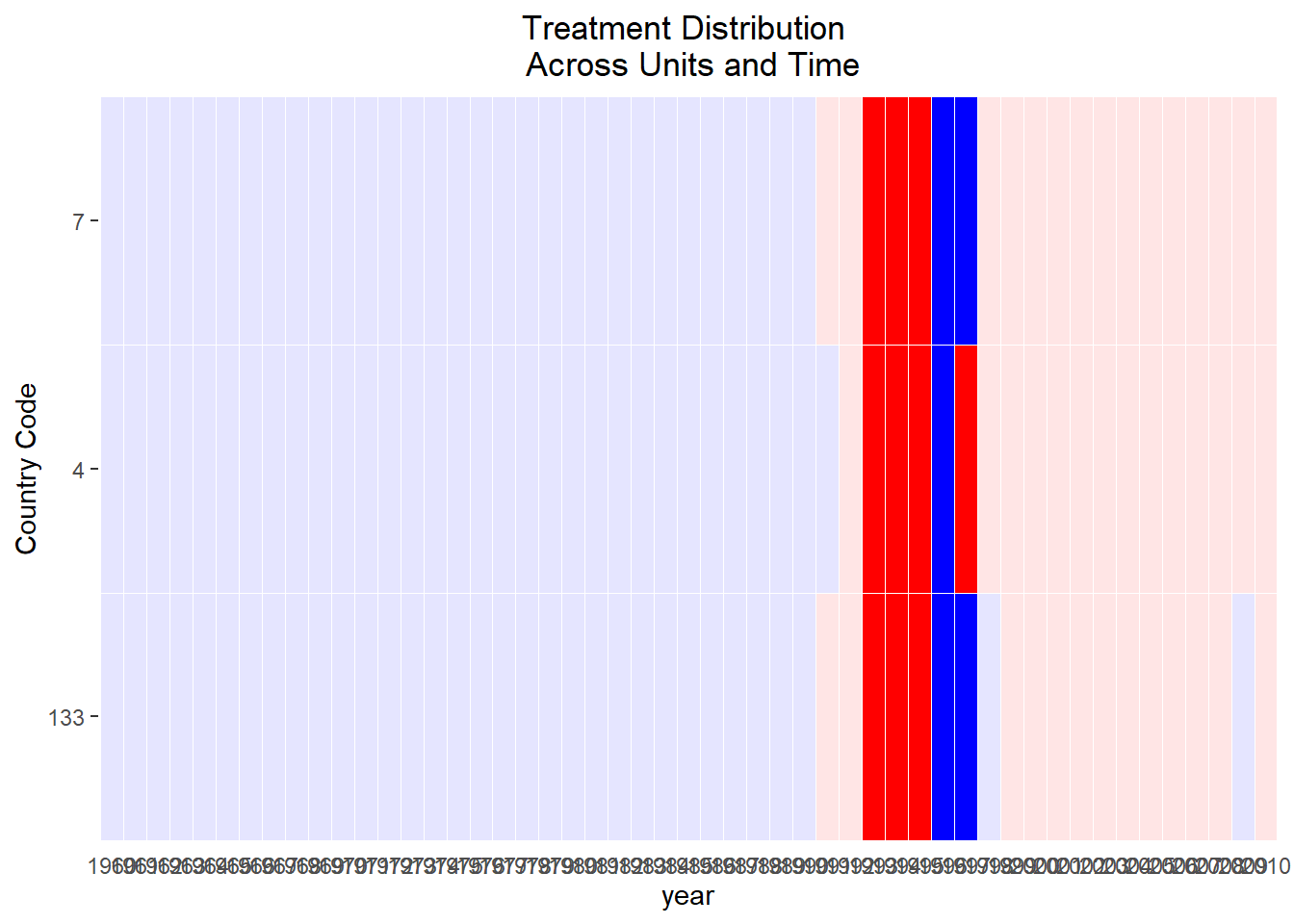

DisplayTreatment(

unit.id = "wbcode2",

time.id = "year",

legend.position = "none",

xlab = "year",

ylab = "Country Code",

treatment = "dem",

data = dem,

matched.set = PM.results.none$att[2],

# highlight the particular set

show.set.only = TRUE

)

This set is more limited than the first one, but we can still see that we have exact past histories.

-

Refining Matched Sets

Refinement involves assigning weights to control units.

-

Users must:

Specify a method for calculating unit similarity/distance.

Choose variables for similarity/distance calculations.

-

Select a Refinement Method

Users determine the refinement method via the

refinement.methodargument.-

Options include:

mahalanobisps.matchCBPS.matchps.weightCBPS.weightps.msm.weightCBPS.msm.weightnone

Methods with “match” in the name and Mahalanobis will assign equal weights to similar control units.

“Weighting” methods give higher weights to control units more similar to treated units.

-

Variable Selection

Users need to define which covariates will be used through the