9 Nonlinear and Generalized Linear Mixed Models

- NLMMs extend the nonlinear model to include both fixed effects and random effects

- GLMMs extend the generalized linear model to include both fixed effects and random effects.

A nonlinear mixed model has the form of

\[ Y_{ij} = f(\mathbf{x_{ij} , \theta, \alpha_i}) + \epsilon_{ij} \]

for the j-th response from cluster (or subject) i (\(i = 1,...,n\)), where

- \(j = 1,...,n_i\)

- \(\mathbf{\theta}\) are the fixed effects

- \(\mathbf{\alpha}_i\) are the random effects for cluster i

- \(\mathbf{x}_{ij}\) are the regressors or design variables

- \(f(.)\) is nonlinear mean response function

A GLMM can be written as:

we assume

\[ y_i |\alpha_i \sim \text{indep } f(y_i | \alpha) \]

and \(f(y_i | \mathbf{\alpha})\) is an exponential family distribution,

\[ f(y_i | \alpha) = \exp [\frac{y_i \theta_i - b(\theta_i)}{a(\phi)} - c(y_i, \phi)] \]

The conditional mean of \(y_i\) is related to \(\theta_i\)

\[ \mu_i = \frac{\partial b(\theta_i)}{\partial \theta_i} \]

The transformation of this mean will give us the desired linear model to model both the fixed and random effects.

\[ \begin{aligned} E(y_i |\alpha) &= \mu_i \\ g(\mu_i) &= \mathbf{x_i' \beta + z'_i \alpha} \end{aligned} \]

where \(g()\) is a known link function and \(\mu_i\) is the conditional mean. We can see similarity to GLM

We also have to specify the random effects distribution

\[ \alpha \sim f(\alpha) \]

which is similar to the specification for mixed models.

Moreover, law of large number applies to fixed effects so that you know it is a normal distribution. But here, you can specify \(\alpha\) subjectively.

Hence, we can show NLMM is a special case of the GLMM

\[ \begin{aligned} \mathbf{Y}_i &= \mathbf{f}(\mathbf{x}_i, \mathbf{\theta, \alpha}_i) + \mathbf{\epsilon}_i \\ \mathbf{Y}_i &= \mathbf{g}^{-1} (\mathbf{x}_i' \beta + \mathbf{z}_i' \mathbf{\alpha}_i) + \mathbf{\epsilon}_i \end{aligned} \]

where the inverse link function corresponds to a nonlinear transformation of the fixed and random effects.

Note:

- we can’t derive the analytical formulation of the marginal distribution because nonlinear combination of normal variables is not normally distributed, even in the case of additive error (\(e_i\)) and random effects (\(\alpha_i\)) are both normal.

Consequences of having random effects

The marginal mean of \(y_i\) is

\[ E(y_i) = E_\alpha(E(y_i | \alpha)) = E_\alpha (\mu_i) = E(g^{-1}(\mathbf{x_i' \beta + z_i' \alpha})) \]

Because \(g^{-1}()\) is nonlinear, this is the most simplified version we can go for.

In special cases such as log link (\(g(\mu) = \log \mu\) or \(g^{-1}() = \exp()\)) then

\[ E(y_i) = E(\exp(\mathbf{x_i' \beta + z_i' \alpha})) = \exp(\mathbf{x'_i \beta})E(\exp(\mathbf{z}_i'\alpha)) \]

which is the moment generating function of \(\alpha\) evaluated at \(\mathbf{z}_i\)

Marginal variance of \(y_i\)

\[ \begin{aligned} var(y_i) &= var_\alpha (E(y_i | \alpha)) + E_\alpha (var(y_i | \alpha)) \\ &= var(\mu_i) + E(a(\phi) V(\mu_i)) \\ &= var(g^{-1} (\mathbf{x'_i \beta + z'_i \alpha})) + E(a(\phi)V(g^{-1} (\mathbf{x'_i \beta + z'_i \alpha}))) \end{aligned} \]

Without specific assumption about \(g()\) and/or the conditional distribution of \(\mathbf{y}\), this is the most simplified version.

Marginal covariance of \(\mathbf{y}\)

In a linear mixed model, random effects introduce a dependence among observations which share any random effect in common

\[ \begin{aligned} cov(y_i, y_j) &= cov_{\alpha}(E(y_i | \mathbf{\alpha}),E(y_j | \mathbf{\alpha})) + E_{\alpha}(cov(y_i, y_j | \mathbf{\alpha})) \\ &= cov(\mu_i, \mu_j) + E(0) \\ &= cov(g^{-1}(\mathbf{x}_i' \beta + \mathbf{z}_i' \mathbf{\alpha}), g^{-1}(\mathbf{x}'_j \beta + \mathbf{z}_j' \mathbf{\alpha})) \end{aligned} \]

- Important: conditioning to induce the covariability

Example:

Repeated measurements on the subjects.

Let \(y_{ij}\) be the j-th count taken on the \(i\)-th subject.

then, the model is \(y_{ij} | \mathbf{\alpha} \sim \text{indep } Pois(\mu_{ij})\). Here

\[ \log(\mu_{ij}) = \mathbf{x}_{ij}' \beta + \alpha_i \]

where \(\alpha_i \sim iid N(0,\sigma^2_{\alpha})\)

which is a log-link with a random patient effect.

9.1 Estimation

In linear mixed models, the marginal likelihood for \(\mathbf{y}\) is the integration of the random effects from the hierarchical formulation

\[ f(\mathbf{y}) = \int f(\mathbf{y}| \alpha) f(\alpha) d \alpha \]

For linear mixed models, we assumed that the 2 component distributions were Gaussian with linear relationships, which implied the marginal distribution was also linear and Gaussian and allows us to solve this integral analytically.

On the other hand, GLMMs, the distribution for \(f(\mathbf{y} | \alpha)\) is not Gaussian in general, and for NLMMs, the functional form between the mean response and the random (and fixed) effects is nonlinear. In both cases, we can’t perform the integral analytically, which means we have to solve it

9.1.1 Estimation by Numerical Integration

The marginal likelihood is

\[ L(\beta; \mathbf{y}) = \int f(\mathbf{y} | \alpha) f(\alpha) d \alpha \]

Estimation fo the fixed effects requires \(\frac{\partial l}{\partial \beta}\), where \(l\) is the log-likelihood

One way to obtain the marginal inference is to numerically integrate out the random effects through

numerical quadrature

Laplace approximation

Monte Carlo methods

When the dimension of \(\mathbf{\alpha}\) is relatively low, this is easy. But when the dimension of \(\alpha\) is high, additional approximation is required.

9.1.2 Estimation by Linearization

Idea: Linearized version of the response (known as working response, or pseudo-response) called \(\tilde{y}_i\) and then the conditional mean is

\[ E(\tilde{y}_i | \alpha) = \mathbf{x}_i' \beta + \mathbf{z}_i' \alpha \]

and also estimate \(var(\tilde{y}_i | \alpha)\). then, apply Linear Mixed Models estimation as usual.

The difference is only in how the linearization is done (i.e., how to expand \(f(\mathbf{x, \theta, \alpha})\) or the inverse link function

9.1.2.1 Penalized quasi-likelihood

(PQL)

This is the more popular method

\[ \tilde{y}_i^{(k)} = \hat{\eta}_i^{(k-1)} + ( y_i - \hat{\mu}_i^{(k-1)})\frac{d \eta}{d \mu}| \hat{\eta}_i^{(k-1)} \]

where

\(\eta_i = g(\mu_i)\) is the linear predictor

\(k\) = iteration of the optimization algorithm

The algorithm updates \(\tilde{y}_i\) after each linear mixed model fit using \(E(\tilde{y}_i | \alpha)\) and \(var(\tilde{y}_i | \alpha)\)

Comments:

Easy to implement

Inference is only asymptotically correct due to the linearizaton

Biased estimates are likely for binomial response with small groups and worst for Bernoulli response. Similarly for Poisson models with small counts. (Faraway 2016)

Hypothesis testing and confidence intervals also have problems.

9.1.2.2 Generalized Estimating Equations

(GEE)

Let a marginal generalized linear model for the mean of y as a function of the predictors, which means we linearize the mean response function and assume a dependent error structure

Example

Binary data:

\[ logit (E(\mathbf{y})) = \mathbf{X} \beta \]

If we assume a “working covariance matrix”, \(\mathbf{V}\) the the elements of \(\mathbf{y}\), then the maximum likelihood equations for estimating \(\beta\) is

\[ \mathbf{X'V^{-1}y} = \mathbf{X'V^{-1}} E(\mathbf{y}) \]

If \(\mathbf{V}\) is correct, then unbiased estimating equations

We typically define \(\mathbf{V} = \mathbf{I}\). Solutions to unbiased estimating equation give consistent estimators.

In practice, we assume a covariance structure, and then do a logistic regression, and calculate its large sample variance

Let \(y_{ij} , j = 1,..,n_i, i = 1,..,K\) be the j-th measurement on the \(i\)-th subject.

\[ \mathbf{y}_i = \left( \begin{array} {c} y_{i1} \\ . \\ y_{in_i} \end{array} \right) \]

with mean

\[ \mathbf{\mu}_i = \left( \begin{array} {c} \mu_{i1} \\ . \\ \mu_{in_i} \end{array} \right) \]

and

\[ \mathbf{x}_{ij} = \left( \begin{array} {c} X_{ij1} \\ . \\ X_{ijp} \end{array} \right) \]

Let \(\mathbf{V}_i = cov(\mathbf{y}_i)\), then based on(Liang and Zeger 1986) GEE estimates for \(\beta\) can be obtained from solving the equation:

\[ S(\beta) = \sum_{i=1}^K \frac{\partial \mathbf{\mu}_i'}{\partial \beta} \mathbf{V}^{-1}(\mathbf{y}_i - \mathbf{\mu}_i) = 0 \]

Let \(\mathbf{R}_i (\mathbf{c})\) be an \(n_i \times n_i\) “working” correlation matrix specified up to some parameters \(\mathbf{c}\). Then, \(\mathbf{V}_i = a(\phi) \mathbf{B}_i^{1/2}\mathbf{R}(\mathbf{c}) \mathbf{B}_i^{1/2}\), where \(\mathbf{B}_i\) is an \(n_i \times n_i\) diagonal matrix with \(V(\mu_{ij})\) on the j-th diagonal

If \(\mathbf{R}(\mathbf{c})\) is the true correlation matrix of \(\mathbf{y}_i\), then \(\mathbf{V}_i\) is the true covariance matrix

The working correlation matrix must be estimated iteratively by a fitting algorithm:

Compute the initial estimate of \(\beta\) (using GLM under the independence assumption)

Compute the working correlation matrix \(\mathbf{R}\) based upon studentized residuals

Compute the estimate covariance \(\hat{\mathbf{V}}_i\)

-

Update \(\beta\) according to

\[ \beta_{r+1} = \beta_r + (\sum_{i=1}^K \frac{\partial \mathbf{\mu}'_i}{\partial \beta} \hat{\mathbf{V}}_i^{-1} \frac{\partial \mathbf{\mu}_i}{\partial \beta}) \]

Iterate until the algorithm converges

Note: Inference based on likelihoods is not appropriate because this is not a likelihood estimator

9.1.3 Estimation by Bayesian Hierarchical Models

Bayesian Estimation

\[ f(\mathbf{\alpha}, \mathbf{\beta} | \mathbf{y}) \propto f(\mathbf{y} | \mathbf{\alpha}, \mathbf{\beta}) f(\mathbf{\alpha})f(\mathbf{\beta}) \]

Numerical techniques (e.g., MCMC) can be used to find posterior distribution. This method is best in terms of not having to make simplifying approximation and fully accounting for uncertainty in estimation and prediction, but it could be complex, time-consuming, and computationally intensive.

Implementation Issues:

No valid joint distribution can be constructed from the given conditional model and random parameters

The mean/ variance relationship and the random effects lead to constraints on the marginal covariance model

Difficult to fit computationally

2 types of estimation approaches:

-

Approximate the objective function (marginal likelihood) through integral approximation

Laplace methods

Quadrature methods

Monte Carlo integration

Approximate the model (based on Taylor series linearization)

Packages in R

GLMM:

MASS:glmmPQLlme4::glmerglmmTMBNLMM:

nlme::nlme;lme4::nlmerbrms::brmBayesian:

MCMCglmm;brms:brm

Example: Non-Gaussian Repeated measurements

When the data are Gaussian, then Linear Mixed Models

When the data are non-Gaussian, then Nonlinear and Generalized Linear Mixed Models

9.2 Application

9.2.1 Binomial (CBPP Data)

data(cbpp,package = "lme4")

head(cbpp)

#> herd incidence size period

#> 1 1 2 14 1

#> 2 1 3 12 2

#> 3 1 4 9 3

#> 4 1 0 5 4

#> 5 2 3 22 1

#> 6 2 1 18 2PQL

Pro:

Linearizes the response to have a pseudo-response as the mean response (like LMM)

computationally efficient

Cons:

biased for binary, Poisson data with small counts

random effects have to be interpreted on the link scale

can’t interpret AIC/BIC value

library(MASS)

pql_cbpp <-

glmmPQL(

cbind(incidence, size - incidence) ~ period,

random = ~ 1 | herd,

data = cbpp,

family = binomial(link = "logit"),

verbose = F

)

summary(pql_cbpp)

#> Linear mixed-effects model fit by maximum likelihood

#> Data: cbpp

#> AIC BIC logLik

#> NA NA NA

#>

#> Random effects:

#> Formula: ~1 | herd

#> (Intercept) Residual

#> StdDev: 0.5563535 1.184527

#>

#> Variance function:

#> Structure: fixed weights

#> Formula: ~invwt

#> Fixed effects: cbind(incidence, size - incidence) ~ period

#> Value Std.Error DF t-value p-value

#> (Intercept) -1.327364 0.2390194 38 -5.553372 0.0000

#> period2 -1.016126 0.3684079 38 -2.758156 0.0089

#> period3 -1.149984 0.3937029 38 -2.920944 0.0058

#> period4 -1.605217 0.5178388 38 -3.099839 0.0036

#> Correlation:

#> (Intr) perid2 perid3

#> period2 -0.399

#> period3 -0.373 0.260

#> period4 -0.282 0.196 0.182

#>

#> Standardized Within-Group Residuals:

#> Min Q1 Med Q3 Max

#> -2.0591168 -0.6493095 -0.2747620 0.5170492 2.6187632

#>

#> Number of Observations: 56

#> Number of Groups: 15

exp(0.556)

#> [1] 1.743684is how the herd specific outcome odds varies.

We can interpret the fixed effect coefficients just like in GLM. Because we use logit link function here, we can say that the log odds of the probability of having a case in period 2 is -1.016 less than period 1 (baseline).

summary(pql_cbpp)$tTable

#> Value Std.Error DF t-value p-value

#> (Intercept) -1.327364 0.2390194 38 -5.553372 2.333216e-06

#> period2 -1.016126 0.3684079 38 -2.758156 8.888179e-03

#> period3 -1.149984 0.3937029 38 -2.920944 5.843007e-03

#> period4 -1.605217 0.5178388 38 -3.099839 3.637000e-03Numerical Integration

Pro:

- more accurate

Con:

computationally expensive

won’t work for complex models.

library(lme4)

numint_cbpp <-

glmer(

cbind(incidence, size - incidence) ~

period + (1 | herd),

data = cbpp,

family = binomial(link = "logit")

)

summary(numint_cbpp)

#> Generalized linear mixed model fit by maximum likelihood (Laplace

#> Approximation) [glmerMod]

#> Family: binomial ( logit )

#> Formula: cbind(incidence, size - incidence) ~ period + (1 | herd)

#> Data: cbpp

#>

#> AIC BIC logLik deviance df.resid

#> 194.1 204.2 -92.0 184.1 51

#>

#> Scaled residuals:

#> Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

#> -2.3816 -0.7889 -0.2026 0.5142 2.8791

#>

#> Random effects:

#> Groups Name Variance Std.Dev.

#> herd (Intercept) 0.4123 0.6421

#> Number of obs: 56, groups: herd, 15

#>

#> Fixed effects:

#> Estimate Std. Error z value Pr(>|z|)

#> (Intercept) -1.3983 0.2312 -6.048 1.47e-09 ***

#> period2 -0.9919 0.3032 -3.272 0.001068 **

#> period3 -1.1282 0.3228 -3.495 0.000474 ***

#> period4 -1.5797 0.4220 -3.743 0.000182 ***

#> ---

#> Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

#>

#> Correlation of Fixed Effects:

#> (Intr) perid2 perid3

#> period2 -0.363

#> period3 -0.340 0.280

#> period4 -0.260 0.213 0.198For small data set, the difference between two approaches are minimal

library(rbenchmark)

benchmark(

"MASS" = {

pql_cbpp <-

glmmPQL(

cbind(incidence, size - incidence) ~ period,

random = ~ 1 | herd,

data = cbpp,

family = binomial(link = "logit"),

verbose = F

)

},

"lme4" = {

glmer(

cbind(incidence, size - incidence) ~ period + (1 | herd),

data = cbpp,

family = binomial(link = "logit")

)

},

replications = 50,

columns = c("test", "replications", "elapsed", "relative"),

order = "relative"

)

#> test replications elapsed relative

#> 1 MASS 50 3.79 1.000

#> 2 lme4 50 7.79 2.055In numerical integration, we can set nAGQ > 1 to switch the method of likelihood evaluation, which might increase accuracy

library(lme4)

numint_cbpp_GH <-

glmer(

cbind(incidence, size - incidence) ~ period + (1 | herd),

data = cbpp,

family = binomial(link = "logit"),

nAGQ = 20

)

summary(numint_cbpp_GH)$coefficients[, 1] -

summary(numint_cbpp)$coefficients[, 1]

#> (Intercept) period2 period3 period4

#> -0.0008808634 0.0005160912 0.0004066218 0.0002644629Bayesian approach to GLMMs

assume the fixed effects parameters have distribution

can handle models with intractable result under traditional methods

computationally expensive

library(MCMCglmm)

Bayes_cbpp <-

MCMCglmm(

cbind(incidence, size - incidence) ~ period,

random = ~ herd,

data = cbpp,

family = "multinomial2",

verbose = FALSE

)

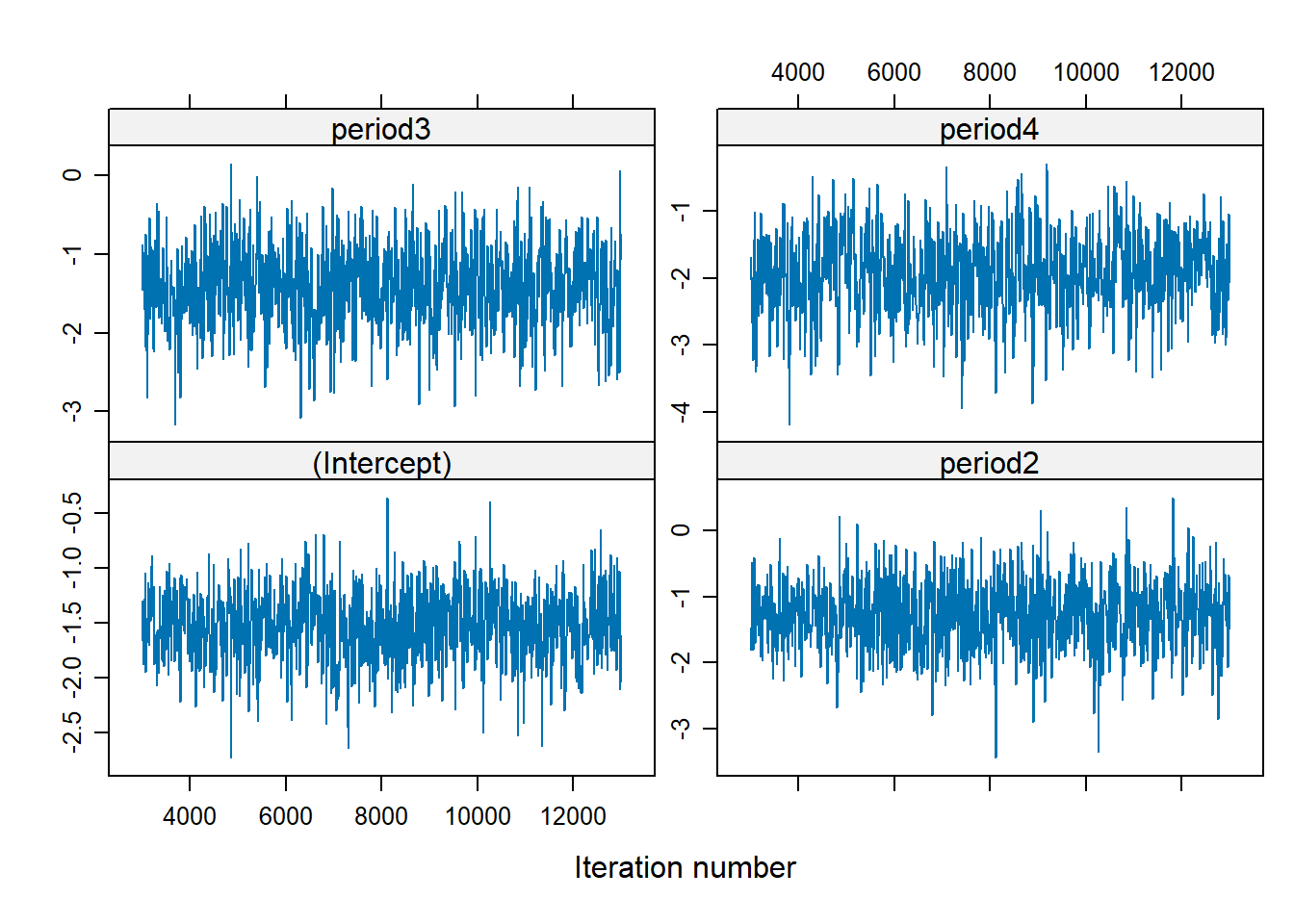

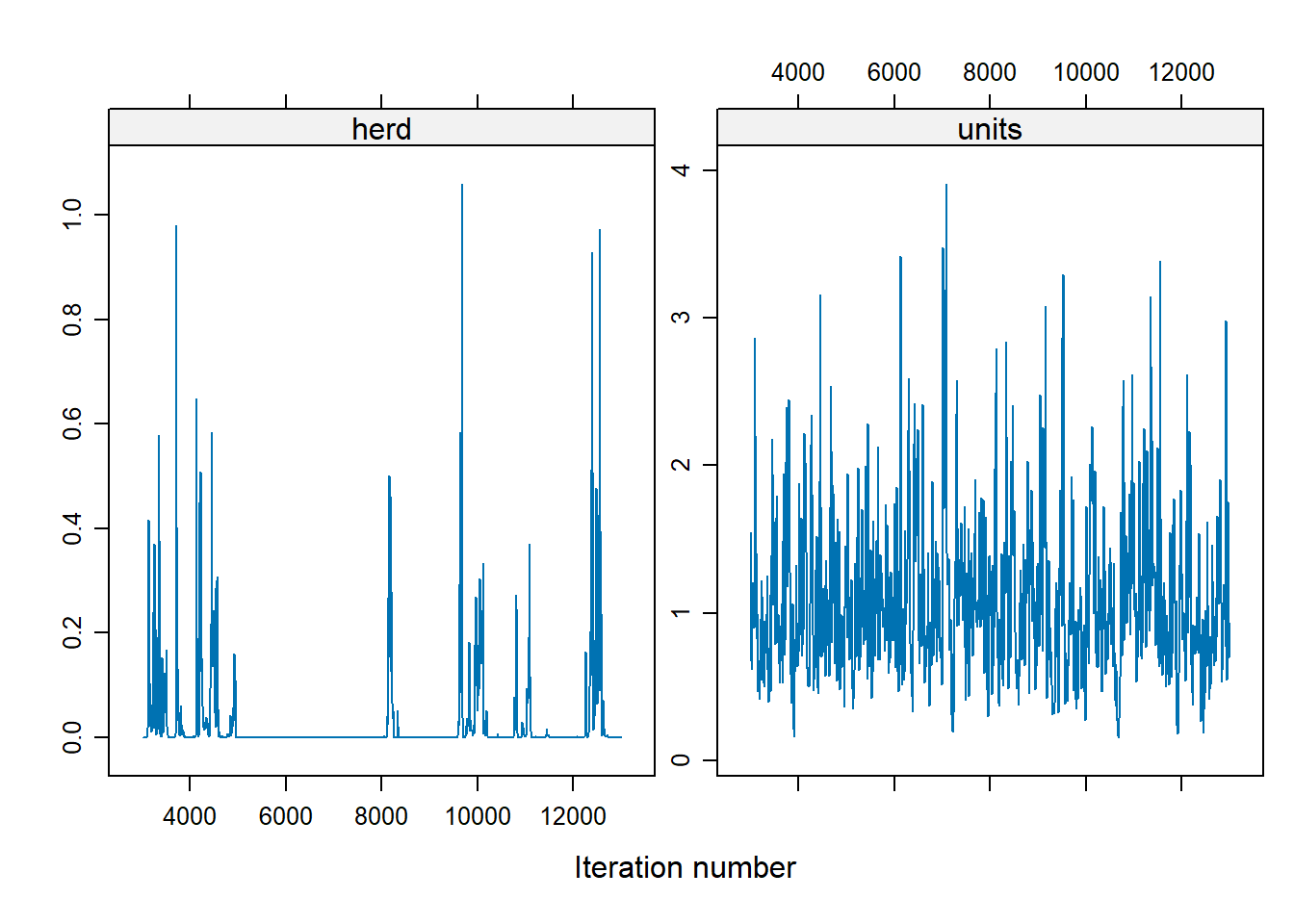

summary(Bayes_cbpp)

#>

#> Iterations = 3001:12991

#> Thinning interval = 10

#> Sample size = 1000

#>

#> DIC: 537.9598

#>

#> G-structure: ~herd

#>

#> post.mean l-95% CI u-95% CI eff.samp

#> herd 0.03246 1.03e-16 0.2073 105.7

#>

#> R-structure: ~units

#>

#> post.mean l-95% CI u-95% CI eff.samp

#> units 1.095 0.3017 2.281 306.9

#>

#> Location effects: cbind(incidence, size - incidence) ~ period

#>

#> post.mean l-95% CI u-95% CI eff.samp pMCMC

#> (Intercept) -1.5247 -2.1732 -0.9248 717.5 <0.001 ***

#> period2 -1.2812 -2.3489 -0.3661 821.7 0.012 *

#> period3 -1.4152 -2.3443 -0.3088 691.5 0.004 **

#> period4 -1.9335 -3.2407 -0.8315 554.9 <0.001 ***

#> ---

#> Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1-

MCMCglmmfits a residual variance component (useful with dispersion issues)

# explains less variability

apply(Bayes_cbpp$VCV,2,sd)

#> herd units

#> 0.1031743 0.5423514

summary(Bayes_cbpp)$solutions

#> post.mean l-95% CI u-95% CI eff.samp pMCMC

#> (Intercept) -1.524731 -2.173223 -0.9247605 717.5157 0.001

#> period2 -1.281212 -2.348887 -0.3660568 821.6596 0.012

#> period3 -1.415170 -2.344293 -0.3087640 691.5463 0.004

#> period4 -1.933501 -3.240745 -0.8314840 554.9365 0.001interpret Bayesian “credible intervals” similarly to confidence intervals

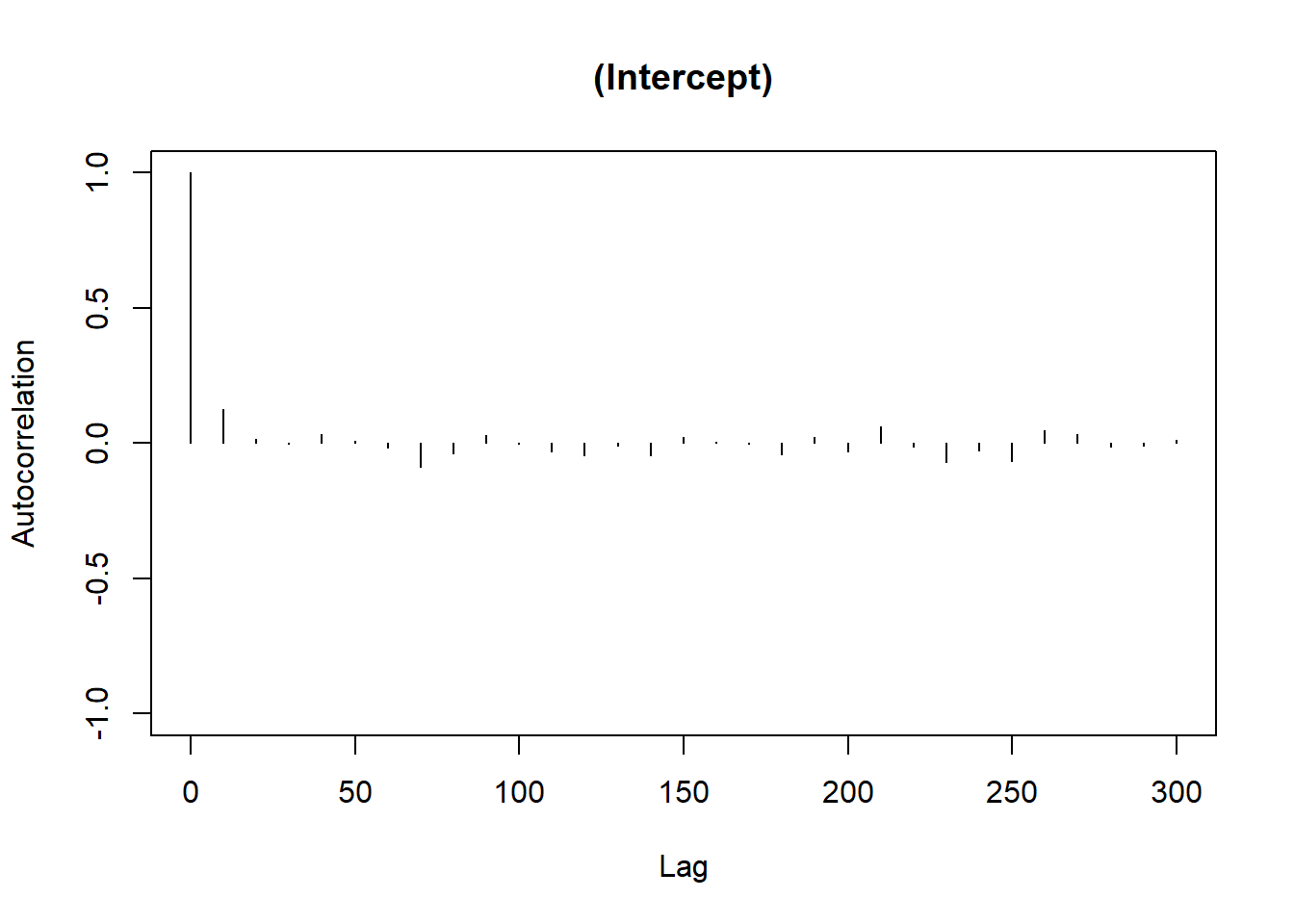

Make sure you make post-hoc diagnoses

There is no trend, well-mixed

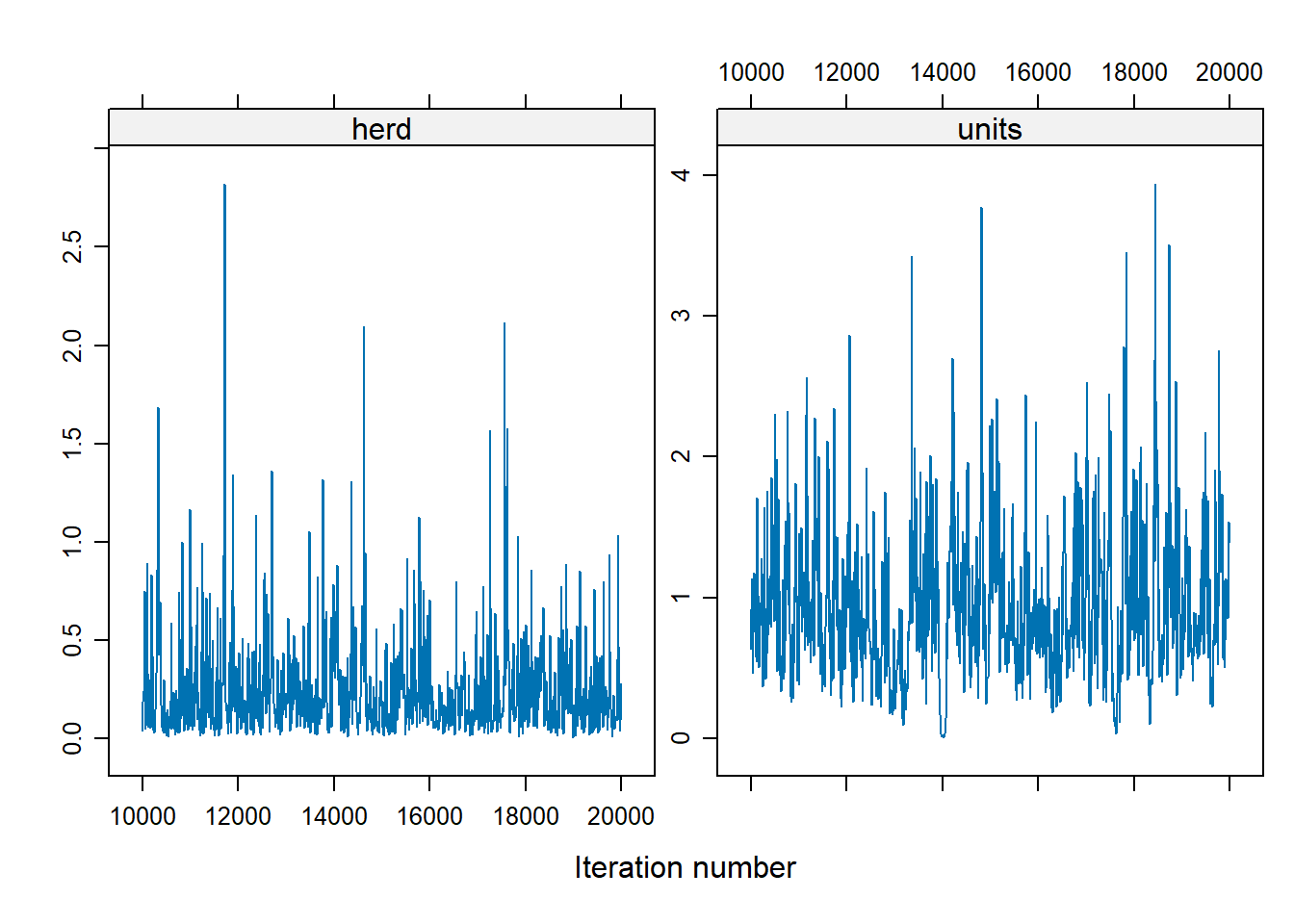

For the herd variable, a lot of them are 0, which suggests problem. To fix the instability in the herd effect sampling, we can either

modify the prior distribution on the herd variation

increases the number of iteration

library(MCMCglmm)

Bayes_cbpp2 <-

MCMCglmm(

cbind(incidence, size - incidence) ~ period,

random = ~ herd,

data = cbpp,

family = "multinomial2",

nitt = 20000,

burnin = 10000,

prior = list(G = list(list(

V = 1, nu = .1

))),

verbose = FALSE

)

xyplot(as.mcmc(Bayes_cbpp2$VCV), layout = c(2, 1))

To change the shape of priors, in MCMCglmm use:

Vcontrols for the location of the distribution (default = 1)nucontrols for the concentration around V (default = 0)

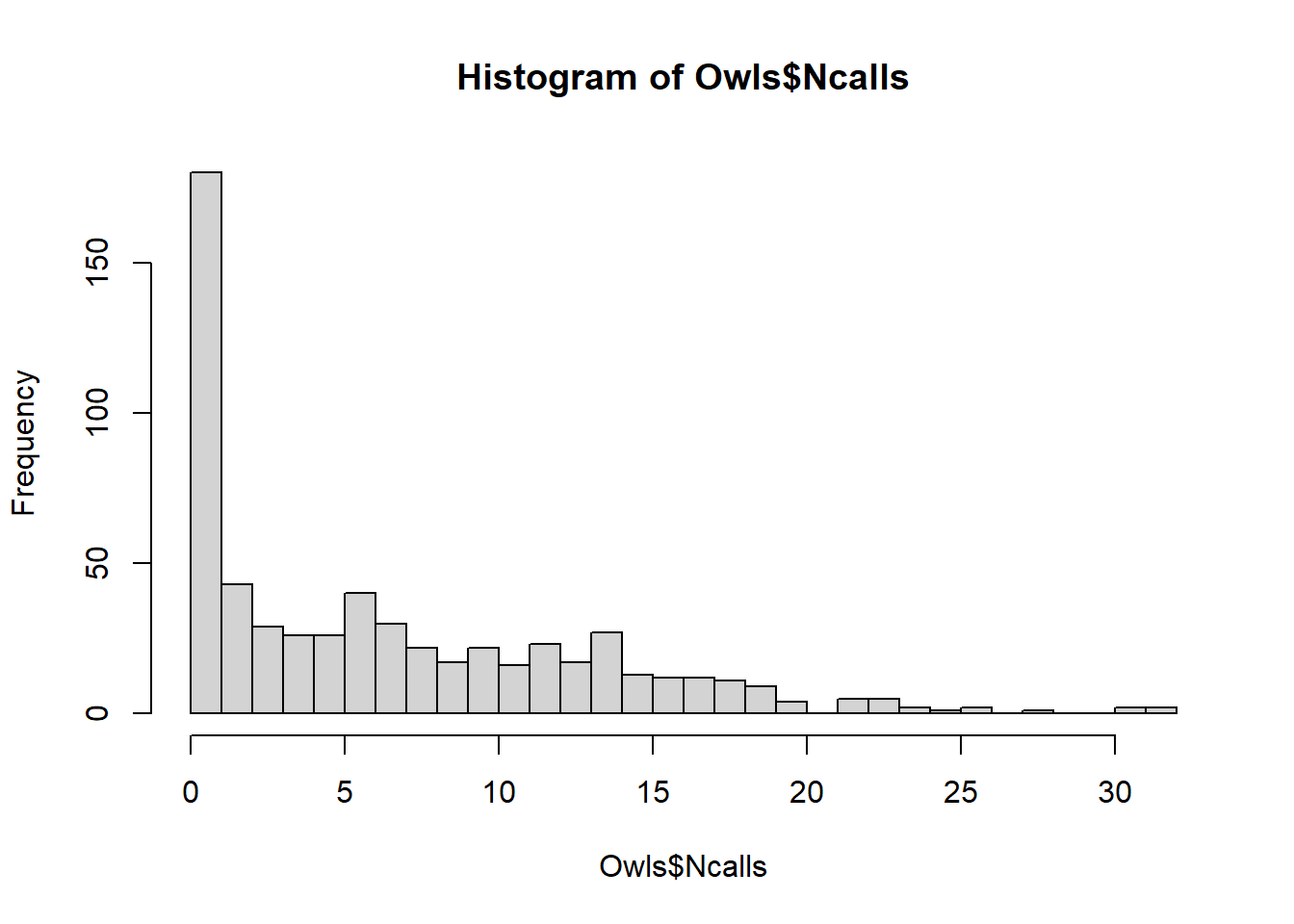

9.2.2 Count (Owl Data)

library(glmmTMB)

library(dplyr)

data(Owls, package = "glmmTMB")

Owls <- Owls %>%

rename(Ncalls = SiblingNegotiation)In a typical Poisson model, \(\lambda\) (Poisson mean), is model as \(\log(\lambda) = \mathbf{x'\beta}\) But if the response is the rate (e.g., counts per BroodSize), we could model it as \(\log(\lambda / b) = \mathbf{x'\beta}\) , equivalently \(\log(\lambda) = \log(b) + \mathbf{x'\beta}\) where \(b\) is BroodSize. Hence, we “offset” the mean by the log of this variable.

owls_glmer <-

glmer(

Ncalls ~ offset(log(BroodSize))

+ FoodTreatment * SexParent +

(1 | Nest),

family = poisson,

data = Owls

)

summary(owls_glmer)

#> Generalized linear mixed model fit by maximum likelihood (Laplace

#> Approximation) [glmerMod]

#> Family: poisson ( log )

#> Formula: Ncalls ~ offset(log(BroodSize)) + FoodTreatment * SexParent +

#> (1 | Nest)

#> Data: Owls

#>

#> AIC BIC logLik deviance df.resid

#> 5212.8 5234.8 -2601.4 5202.8 594

#>

#> Scaled residuals:

#> Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

#> -3.5529 -1.7971 -0.6842 1.2689 11.4312

#>

#> Random effects:

#> Groups Name Variance Std.Dev.

#> Nest (Intercept) 0.2063 0.4542

#> Number of obs: 599, groups: Nest, 27

#>

#> Fixed effects:

#> Estimate Std. Error z value Pr(>|z|)

#> (Intercept) 0.65585 0.09567 6.855 7.12e-12 ***

#> FoodTreatmentSatiated -0.65612 0.05606 -11.705 < 2e-16 ***

#> SexParentMale -0.03705 0.04501 -0.823 0.4104

#> FoodTreatmentSatiated:SexParentMale 0.13135 0.07036 1.867 0.0619 .

#> ---

#> Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

#>

#> Correlation of Fixed Effects:

#> (Intr) FdTrtS SxPrnM

#> FdTrtmntStt -0.225

#> SexParentMl -0.292 0.491

#> FdTrtmS:SPM 0.170 -0.768 -0.605nest explains a relatively large proportion of the variability (its standard deviation is larger than some coefficients)

the model fit isn’t great (deviance of 5202 on 594 df)

# Negative binomial model

owls_glmerNB <-

glmer.nb(Ncalls ~ offset(log(BroodSize))

+ FoodTreatment * SexParent

+ (1 | Nest), data = Owls)

c(Deviance = round(summary(owls_glmerNB)$AICtab["deviance"], 3),

df = summary(owls_glmerNB)$AICtab["df.resid"])

#> Deviance.deviance df.df.resid

#> 3483.616 593.000There is an improvement using negative binomial considering over-dispersion

hist(Owls$Ncalls,breaks=30)

To account for too many 0s in these data, we can use zero-inflated Poisson (ZIP) model.

-

glmmTMBcan handle ZIP GLMMs since it adds automatic differentiation to existing estimation strategies.

library(glmmTMB)

owls_glmm <-

glmmTMB(

Ncalls ~ FoodTreatment * SexParent + offset(log(BroodSize)) +

(1 | Nest),

ziformula = ~ 0,

family = nbinom2(link = "log"),

data = Owls

)

owls_glmm_zi <-

glmmTMB(

Ncalls ~ FoodTreatment * SexParent + offset(log(BroodSize)) +

(1 | Nest),

ziformula = ~ 1,

family = nbinom2(link = "log"),

data = Owls

)

# Scale Arrival time to use as a covariate for zero-inflation parameter

Owls$ArrivalTime <- scale(Owls$ArrivalTime)

owls_glmm_zi_cov <- glmmTMB(

Ncalls ~ FoodTreatment * SexParent +

offset(log(BroodSize)) +

(1 | Nest),

ziformula = ~ ArrivalTime,

family = nbinom2(link = "log"),

data = Owls

)

as.matrix(anova(owls_glmm, owls_glmm_zi))

#> Df AIC BIC logLik deviance Chisq Chi Df

#> owls_glmm 6 3495.610 3521.981 -1741.805 3483.610 NA NA

#> owls_glmm_zi 7 3431.646 3462.413 -1708.823 3417.646 65.96373 1

#> Pr(>Chisq)

#> owls_glmm NA

#> owls_glmm_zi 4.592983e-16

as.matrix(anova(owls_glmm_zi, owls_glmm_zi_cov))

#> Df AIC BIC logLik deviance Chisq Chi Df

#> owls_glmm_zi 7 3431.646 3462.413 -1708.823 3417.646 NA NA

#> owls_glmm_zi_cov 8 3422.532 3457.694 -1703.266 3406.532 11.11411 1

#> Pr(>Chisq)

#> owls_glmm_zi NA

#> owls_glmm_zi_cov 0.0008567362

summary(owls_glmm_zi_cov)

#> Family: nbinom2 ( log )

#> Formula:

#> Ncalls ~ FoodTreatment * SexParent + offset(log(BroodSize)) + (1 | Nest)

#> Zero inflation: ~ArrivalTime

#> Data: Owls

#>

#> AIC BIC logLik deviance df.resid

#> 3422.5 3457.7 -1703.3 3406.5 591

#>

#> Random effects:

#>

#> Conditional model:

#> Groups Name Variance Std.Dev.

#> Nest (Intercept) 0.07487 0.2736

#> Number of obs: 599, groups: Nest, 27

#>

#> Dispersion parameter for nbinom2 family (): 2.22

#>

#> Conditional model:

#> Estimate Std. Error z value Pr(>|z|)

#> (Intercept) 0.84778 0.09961 8.511 < 2e-16 ***

#> FoodTreatmentSatiated -0.39529 0.13742 -2.877 0.00402 **

#> SexParentMale -0.07025 0.10435 -0.673 0.50079

#> FoodTreatmentSatiated:SexParentMale 0.12388 0.16449 0.753 0.45138

#> ---

#> Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

#>

#> Zero-inflation model:

#> Estimate Std. Error z value Pr(>|z|)

#> (Intercept) -1.3018 0.1261 -10.32 < 2e-16 ***

#> ArrivalTime 0.3545 0.1074 3.30 0.000966 ***

#> ---

#> Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1We can see ZIP GLMM with an arrival time covariate on the zero is best.

arrival time has a positive effect on observing a nonzero number of calls

interactions are non significant, the food treatment is significant (fewer calls after eating)

nest variability is large in magnitude (without this, the parameter estimates change)

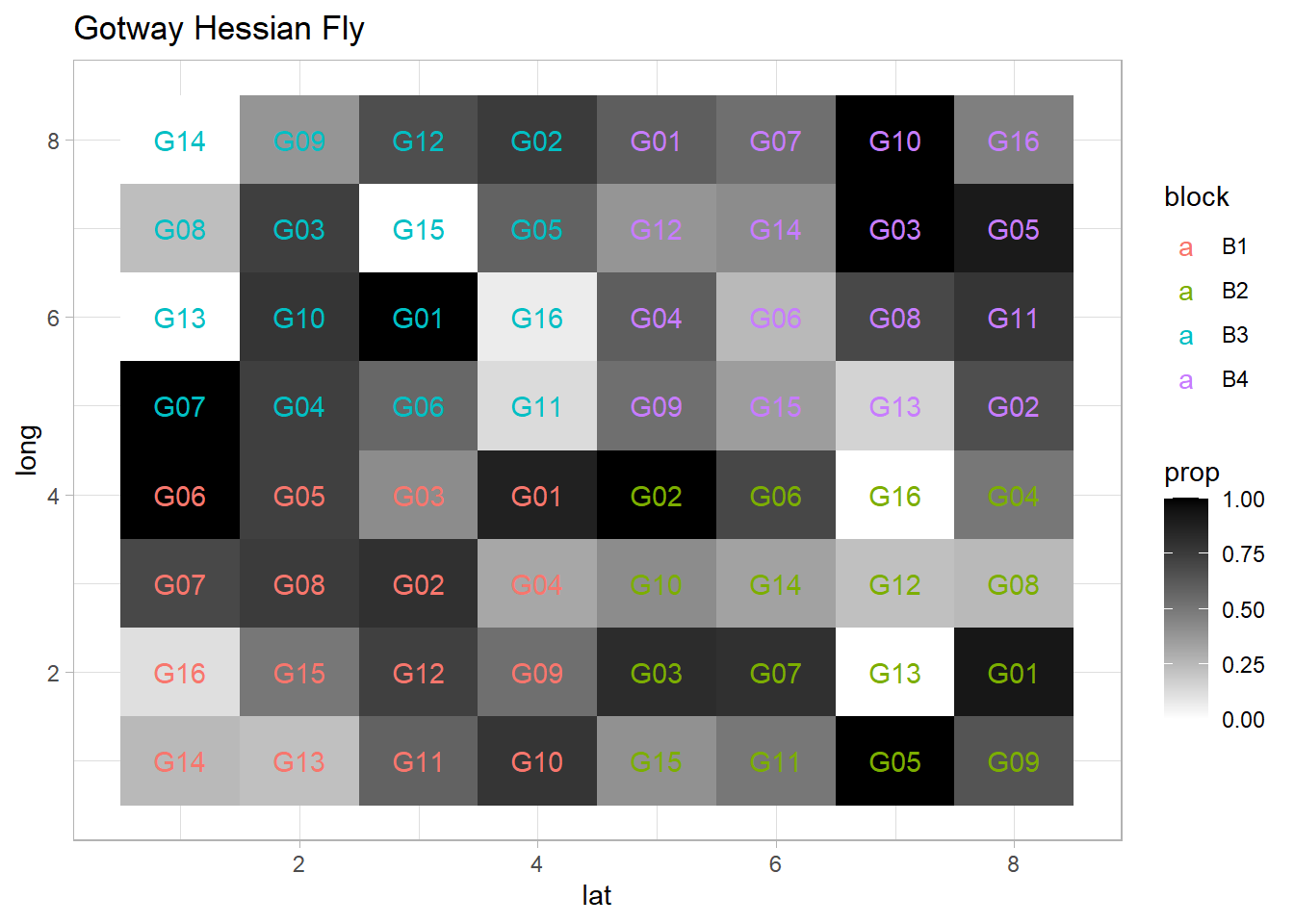

9.2.3 Binomial

library(agridat)

library(ggplot2)

library(lme4)

library(spaMM)

data(gotway.hessianfly)

dat <- gotway.hessianfly

dat$prop <- dat$y / dat$n

ggplot(dat, aes(x = lat, y = long, fill = prop)) +

geom_tile() +

scale_fill_gradient(low = 'white', high = 'black') +

geom_text(aes(label = gen, color = block)) +

ggtitle('Gotway Hessian Fly')

Fixed effects (\(\beta\)) = genotype

Random effects (\(\alpha\)) = block

flymodel <-

glmer(

cbind(y, n - y) ~ gen + (1 | block),

data = dat,

family = binomial,

nAGQ = 5

)

summary(flymodel)

#> Generalized linear mixed model fit by maximum likelihood (Adaptive

#> Gauss-Hermite Quadrature, nAGQ = 5) [glmerMod]

#> Family: binomial ( logit )

#> Formula: cbind(y, n - y) ~ gen + (1 | block)

#> Data: dat

#>

#> AIC BIC logLik deviance df.resid

#> 162.2 198.9 -64.1 128.2 47

#>

#> Scaled residuals:

#> Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

#> -2.38644 -1.01188 0.09631 1.03468 2.75479

#>

#> Random effects:

#> Groups Name Variance Std.Dev.

#> block (Intercept) 0.001022 0.03196

#> Number of obs: 64, groups: block, 4

#>

#> Fixed effects:

#> Estimate Std. Error z value Pr(>|z|)

#> (Intercept) 1.5035 0.3914 3.841 0.000122 ***

#> genG02 -0.1939 0.5302 -0.366 0.714644

#> genG03 -0.5408 0.5103 -1.060 0.289260

#> genG04 -1.4342 0.4714 -3.043 0.002346 **

#> genG05 -0.2037 0.5429 -0.375 0.707486

#> genG06 -0.9783 0.5046 -1.939 0.052533 .

#> genG07 -0.6041 0.5111 -1.182 0.237235

#> genG08 -1.6774 0.4907 -3.418 0.000630 ***

#> genG09 -1.3984 0.4725 -2.960 0.003078 **

#> genG10 -0.6817 0.5333 -1.278 0.201181

#> genG11 -1.4630 0.4843 -3.021 0.002522 **

#> genG12 -1.4591 0.4918 -2.967 0.003010 **

#> genG13 -3.5528 0.6600 -5.383 7.31e-08 ***

#> genG14 -2.5073 0.5264 -4.763 1.90e-06 ***

#> genG15 -2.0872 0.4851 -4.302 1.69e-05 ***

#> genG16 -2.9697 0.5383 -5.517 3.46e-08 ***

#> ---

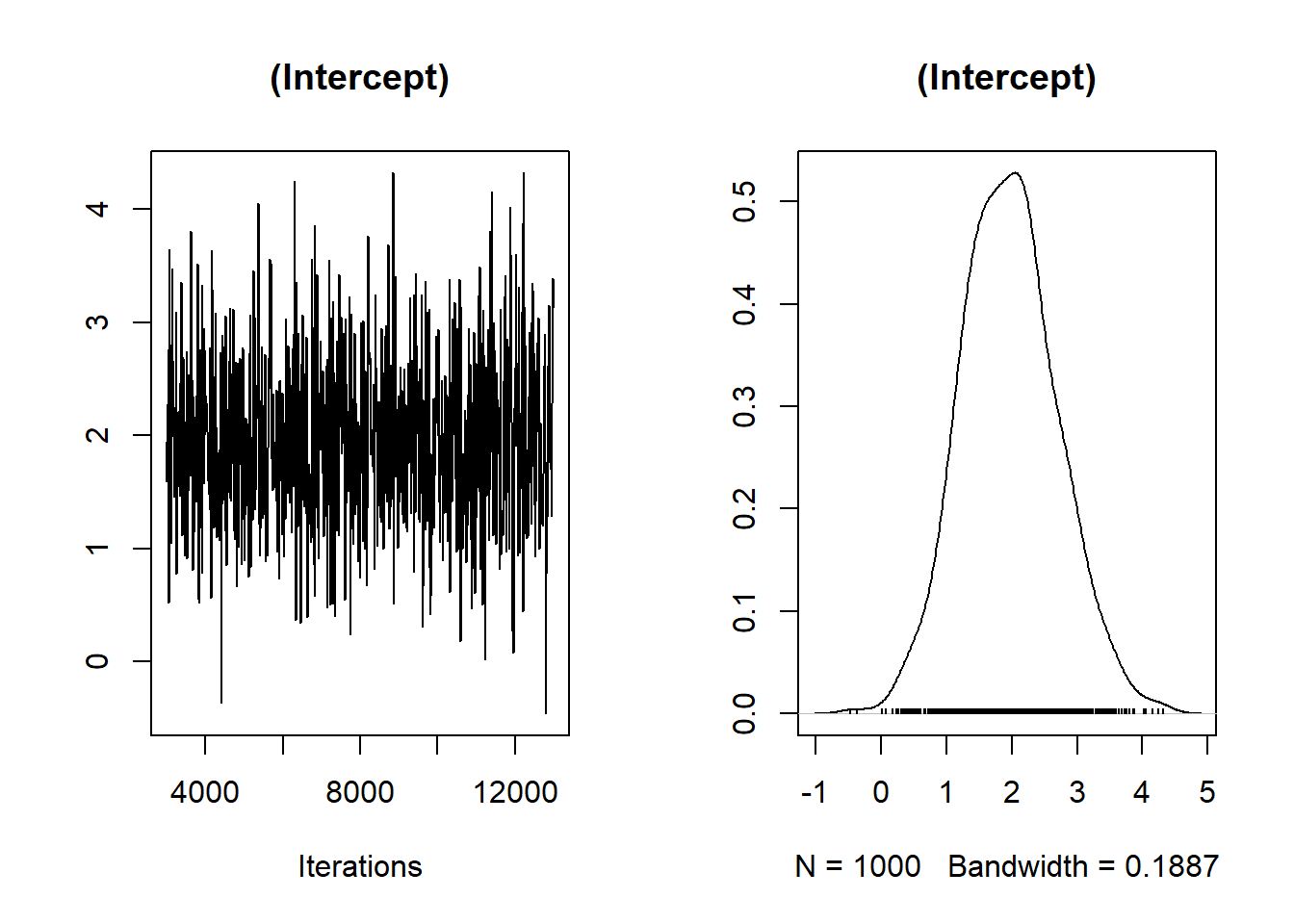

#> Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1Equivalently, we can use MCMCglmm , for a Bayesian approach

library(coda)

Bayes_flymodel <- MCMCglmm(

cbind(y, n - y) ~ gen ,

random = ~ block,

data = dat,

family = "multinomial2",

verbose = FALSE

)

plot(Bayes_flymodel$Sol[, 1], main = dimnames(Bayes_flymodel$Sol)[[2]][1])

autocorr.plot(Bayes_flymodel$Sol[, 1], main = dimnames(Bayes_flymodel$Sol)[[2]][1])

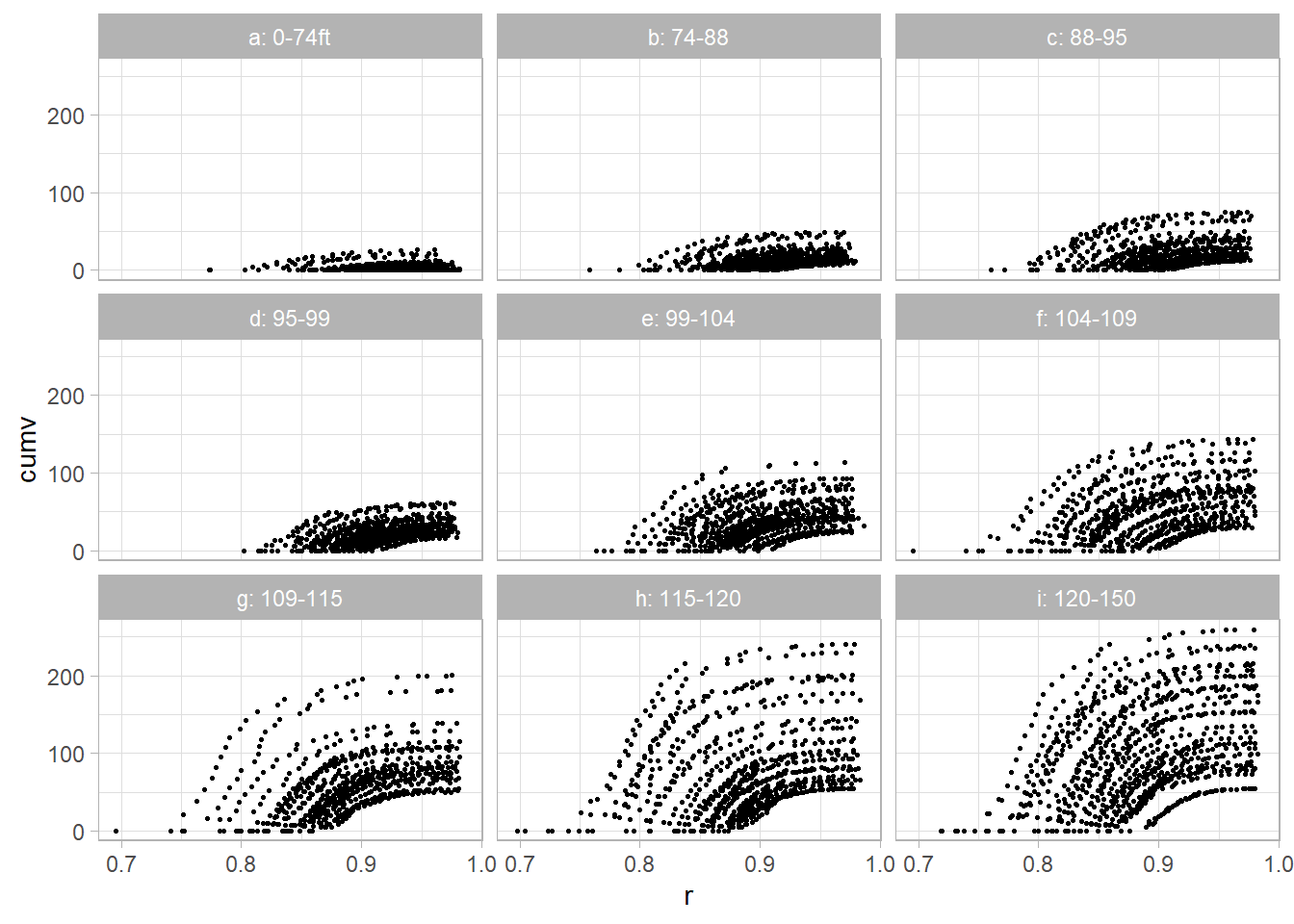

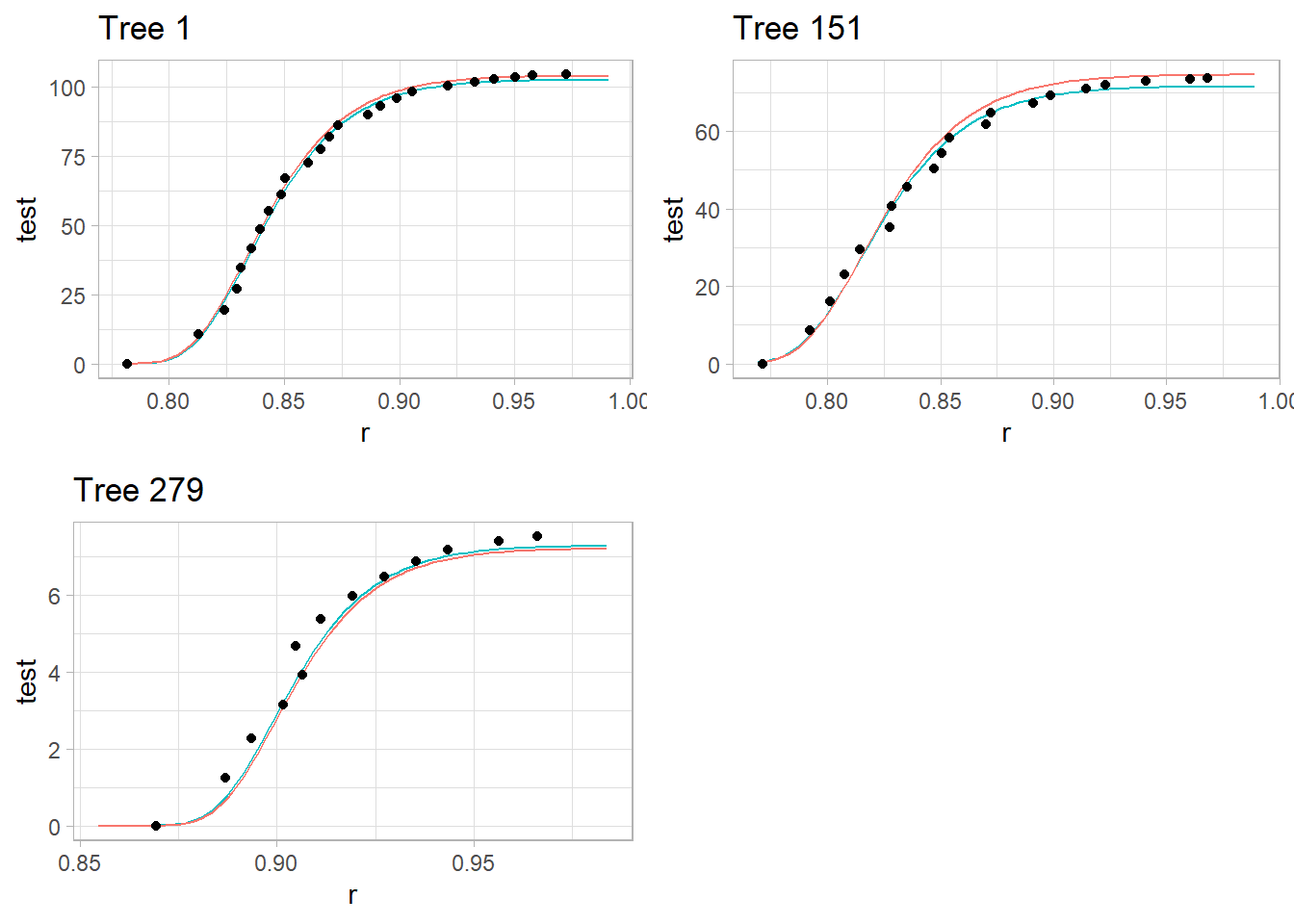

9.2.4 Example from (Schabenberger and Pierce 2001) section 8.4.1

dat2 <- read.table("images/YellowPoplarData_r.txt")

names(dat2) <- c('tn', 'k', 'dbh', 'totht',

'dob', 'ht', 'maxd', 'cumv')

dat2$t <- dat2$dob / dat2$dbh

dat2$r <- 1 - dat2$dob / dat2$tothtThe cumulative volume relates to the complementary diameter (subplots were created based on total tree height)

library(ggplot2)

library(dplyr)

dat2 <- dat2 %>% group_by(tn) %>% mutate(

z = case_when(

totht < 74 & totht >= 0 ~ 'a: 0-74ft',

totht < 88 & totht >= 74 ~ 'b: 74-88',

totht < 95 & totht >= 88 ~ 'c: 88-95',

totht < 99 & totht >= 95 ~ 'd: 95-99',

totht < 104 & totht >= 99 ~ 'e: 99-104',

totht < 109 & totht >= 104 ~ 'f: 104-109',

totht < 115 & totht >= 109 ~ 'g: 109-115',

totht < 120 & totht >= 115 ~ 'h: 115-120',

totht < 140 & totht >= 120 ~ 'i: 120-150',

)

)

ggplot(dat2, aes(x = r, y = cumv)) +

geom_point(size = 0.5) +

facet_wrap(vars(z))

The proposed non-linear model:

\[ V_{id_j} = (\beta_0 + (\beta_1 + b_{1i})\frac{D^2_i H_i}{1000})(\exp[-(\beta_2 + b_{2i})t_{ij} \exp(\beta_3 t_{ij})]) + e_{ij} \]

where

\(b_{1i}, b_{2i}\) are random effects

\(e_{ij}\) are random errors

library(nlme)

tmp <-

nlme(

cumv ~ (b0 + (b1 + u1) *

(dbh * dbh * totht / 1000)) *

(exp(-(b2 + u2) * (t / 1000) * exp(b3 * t))),

data = dat2,

fixed = b0 + b1 + b2 + b3 ~ 1,

# 1 on the right hand side of the formula indicates

# a single fixed effects for the corresponding parameters

random = list(pdDiag(u1 + u2 ~ 1)),

#uncorrelated random effects

groups = ~ tn,

#group on trees so each tree w/ have u1 and u2

start = list(fixed = c(

b0 = 0.25,

b1 = 2.3,

b2 = 2.87,

b3 = 6.7

))

)

summary(tmp)

#> Nonlinear mixed-effects model fit by maximum likelihood

#> Model: cumv ~ (b0 + (b1 + u1) * (dbh * dbh * totht/1000)) * (exp(-(b2 + u2) * (t/1000) * exp(b3 * t)))

#> Data: dat2

#> AIC BIC logLik

#> 31103.73 31151.33 -15544.86

#>

#> Random effects:

#> Formula: list(u1 ~ 1, u2 ~ 1)

#> Level: tn

#> Structure: Diagonal

#> u1 u2 Residual

#> StdDev: 0.1508094 0.447829 2.226361

#>

#> Fixed effects: b0 + b1 + b2 + b3 ~ 1

#> Value Std.Error DF t-value p-value

#> b0 0.249386 0.12894687 6297 1.9340 0.0532

#> b1 2.288832 0.01266804 6297 180.6776 0.0000

#> b2 2.500497 0.05606685 6297 44.5985 0.0000

#> b3 6.848871 0.02140677 6297 319.9395 0.0000

#> Correlation:

#> b0 b1 b2

#> b1 -0.639

#> b2 0.054 0.056

#> b3 -0.011 -0.066 -0.850

#>

#> Standardized Within-Group Residuals:

#> Min Q1 Med Q3 Max

#> -6.694575e+00 -3.081861e-01 -8.904304e-05 3.469469e-01 7.855665e+00

#>

#> Number of Observations: 6636

#> Number of Groups: 336

nlme::intervals(tmp)

#> Approximate 95% confidence intervals

#>

#> Fixed effects:

#> lower est. upper

#> b0 -0.003318061 0.2493855 0.5020892

#> b1 2.264006036 2.2888322 2.3136584

#> b2 2.390620340 2.5004973 2.6103743

#> b3 6.806919342 6.8488713 6.8908232

#>

#> Random Effects:

#> Level: tn

#> lower est. upper

#> sd(u1) 0.1376084 0.1508094 0.1652768

#> sd(u2) 0.4056209 0.4478290 0.4944291

#>

#> Within-group standard error:

#> lower est. upper

#> 2.187258 2.226361 2.266162- Little different from the book because of different implementation of nonlinear mixed models.

library(cowplot)

nlmmfn <- function(fixed,rand,dbh,totht,t){

b0 <- fixed[1]

b1 <- fixed[2]

b2 <- fixed[3]

b3 <- fixed[4]

u1 <- rand[1]

u2 <- rand[2]

#just made so we can predict w/o random effects

return((b0+(b1+u1)*(dbh*dbh*totht/1000))*(exp(-(b2+u2)*(t/1000)*exp(b3*t))))

}

#Tree 1

pred1 <- data.frame(seq(1, 24, length.out = 100))

names(pred1) <- 'dob'

pred1$tn <- 1

pred1$dbh <- unique(dat2[dat2$tn == 1, ]$dbh)

pred1$t <- pred1$dob / pred1$dbh

pred1$totht <- unique(dat2[dat2$tn == 1, ]$totht)

pred1$r <- 1 - pred1$dob / pred1$totht

pred1$test <- predict(tmp, pred1)

pred1$testno <-

nlmmfn(

fixed = tmp$coefficients$fixed,

rand = c(0, 0),

pred1$dbh,

pred1$totht,

pred1$t

)

p1 <-

ggplot(pred1) +

geom_line(aes(x = r, y = test, color = 'with random')) +

geom_line(aes(x = r, y = testno, color = 'No random')) +

labs(colour = "") +

geom_point(data = dat2[dat2$tn == 1, ], aes(x = r, y = cumv)) +

ggtitle('Tree 1') + theme(legend.position = "none")

#Tree 151

pred151 <- data.frame(seq(1, 21, length.out = 100))

names(pred151) <- 'dob'

pred151$tn <- 151

pred151$dbh <- unique(dat2[dat2$tn == 151, ]$dbh)

pred151$t <- pred151$dob / pred151$dbh

pred151$totht <- unique(dat2[dat2$tn == 151, ]$totht)

pred151$r <- 1 - pred151$dob / pred151$totht

pred151$test <- predict(tmp, pred151)

pred151$testno <-

nlmmfn(

fixed = tmp$coefficients$fixed,

rand = c(0, 0),

pred151$dbh,

pred151$totht,

pred151$t

)

p2 <-

ggplot(pred151) +

geom_line(aes(x = r, y = test, color = 'with random')) +

geom_line(aes(x = r, y = testno, color = 'No random')) +

labs(colour = "") +

geom_point(data = dat2[dat2$tn == 151,], aes(x = r, y = cumv)) +

ggtitle('Tree 151') +

theme(legend.position = "none")

#Tree 279

pred279 <- data.frame(seq(1, 9, length.out = 100))

names(pred279) <- 'dob'

pred279$tn <- 279

pred279$dbh <- unique(dat2[dat2$tn == 279, ]$dbh)

pred279$t <- pred279$dob / pred279$dbh

pred279$totht <- unique(dat2[dat2$tn == 279, ]$totht)

pred279$r <- 1 - pred279$dob / pred279$totht

pred279$test <- predict(tmp, pred279)

pred279$testno <-

nlmmfn(

fixed = tmp$coefficients$fixed,

rand = c(0, 0),

pred279$dbh,

pred279$totht,

pred279$t

)

p3 <-

ggplot(pred279) +

geom_line(aes(x = r, y = test, color = 'with random')) +

geom_line(aes(x = r, y = testno, color = 'No random')) +

labs(colour = "") +

geom_point(data = dat2[dat2$tn == 279, ], aes(x = r, y = cumv)) +

ggtitle('Tree 279') +

theme(legend.position = "none")

plot_grid(p1, p2, p3)

red line = predicted observations based on the common fixed effects

teal line = tree-specific predictions with random effects