22 Multivariate Methods

\(y_1,...,y_p\) are possibly correlated random variables with means \(\mu_1,...,\mu_p\)

\[ \mathbf{y} = \left( \begin{array} {c} y_1 \\ . \\ y_p \\ \end{array} \right) \]

\[ E(\mathbf{y}) = \left( \begin{array} {c} \mu_1 \\ . \\ \mu_p \\ \end{array} \right) \]

Let \(\sigma_{ij} = cov(y_i, y_j)\) for \(i,j = 1,…,p\)

\[ \mathbf{\Sigma} = (\sigma_{ij}) = \left( \begin{array} {cccc} \sigma_{11} & \sigma_{22} & ... & \sigma_{1p} \\ \sigma_{21} & \sigma_{22} & ... & \sigma_{2p} \\ . & . & . & . \\ \sigma_{p1} & \sigma_{p2} & ... & \sigma_{pp} \end{array} \right) \]

where \(\mathbf{\Sigma}\) (symmetric) is the variance-covariance or dispersion matrix

Let \(\mathbf{u}_{p \times 1}\) and \(\mathbf{v}_{q \times 1}\) be random vectors with means \(\mu_u\) and \(\mu_v\) . Then

\[ \mathbf{\Sigma}_{uv} = cov(\mathbf{u,v}) = E[(\mathbf{u} - \mu_u)(\mathbf{v} - \mu_v)'] \]

in which \(\mathbf{\Sigma}_{uv} \neq \mathbf{\Sigma}_{vu}\) and \(\mathbf{\Sigma}_{uv} = \mathbf{\Sigma}_{vu}'\)

Properties of Covariance Matrices

- Symmetric \(\mathbf{\Sigma}' = \mathbf{\Sigma}\)

- Non-negative definite \(\mathbf{a'\Sigma a} \ge 0\) for any \(\mathbf{a} \in R^p\), which is equivalent to eigenvalues of \(\mathbf{\Sigma}\), \(\lambda_1 \ge \lambda_2 \ge ... \ge \lambda_p \ge 0\)

- \(|\mathbf{\Sigma}| = \lambda_1 \lambda_2 ... \lambda_p \ge 0\) (generalized variance) (the bigger this number is, the more variation there is

- \(trace(\mathbf{\Sigma}) = tr(\mathbf{\Sigma}) = \lambda_1 + ... + \lambda_p = \sigma_{11} + ... + \sigma_{pp} =\) sum of variance (total variance)

Note:

- \(\mathbf{\Sigma}\) is typically required to be positive definite, which means all eigenvalues are positive, and \(\mathbf{\Sigma}\) has an inverse \(\mathbf{\Sigma}^{-1}\) such that \(\mathbf{\Sigma}^{-1}\mathbf{\Sigma} = \mathbf{I}_{p \times p} = \mathbf{\Sigma \Sigma}^{-1}\)

Correlation Matrices

\[ \rho_{ij} = \frac{\sigma_{ij}}{\sqrt{\sigma_{ii} \sigma_{jj}}} \]

\[ \mathbf{R} = \left( \begin{array} {cccc} \rho_{11} & \rho_{12} & ... & \rho_{1p} \\ \rho_{21} & \rho_{22} & ... & \rho_{2p} \\ . & . & . &. \\ \rho_{p1} & \rho_{p2} & ... & \rho_{pp} \\ \end{array} \right) \]

where \(\rho_{ij}\) is the correlation, and \(\rho_{ii} = 1\) for all i

Alternatively,

\[ \mathbf{R} = [diag(\mathbf{\Sigma})]^{-1/2}\mathbf{\Sigma}[diag(\mathbf{\Sigma})]^{-1/2} \]

where \(diag(\mathbf{\Sigma})\) is the matrix which has the \(\sigma_{ii}\)’s on the diagonal and 0’s elsewhere

and \(\mathbf{A}^{1/2}\) (the square root of a symmetric matrix) is a symmetric matrix such as \(\mathbf{A} = \mathbf{A}^{1/2}\mathbf{A}^{1/2}\)

Equalities

Let

\(\mathbf{x}\) and \(\mathbf{y}\) be random vectors with means \(\mu_x\) and \(\mu_y\) and variance -variance matrices \(\mathbf{\Sigma}_x\) and \(\mathbf{\Sigma}_y\).

\(\mathbf{A}\) and \(\mathbf{B}\) be matrices of constants and \(\mathbf{c}\) and \(\mathbf{d}\) be vectors of constants

Then

\(E(\mathbf{Ay + c} ) = \mathbf{A} \mu_y + c\)

\(var(\mathbf{Ay + c}) = \mathbf{A} var(\mathbf{y})\mathbf{A}' = \mathbf{A \Sigma_y A}'\)

\(cov(\mathbf{Ay + c, By+ d}) = \mathbf{A\Sigma_y B}'\)

\(E(\mathbf{Ay + Bx + c}) = \mathbf{A \mu_y + B \mu_x + c}\)

\(var(\mathbf{Ay + Bx + c}) = \mathbf{A \Sigma_y A' + B \Sigma_x B' + A \Sigma_{yx}B' + B\Sigma'_{yx}A'}\)

Multivariate Normal Distribution

Let \(\mathbf{y}\) be a multivariate normal (MVN) random variable with mean \(\mu\) and variance \(\mathbf{\Sigma}\). Then the density of \(\mathbf{y}\) is

\[ f(\mathbf{y}) = \frac{1}{(2\pi)^{p/2}|\mathbf{\Sigma}|^{1/2}} \exp(-\frac{1}{2} \mathbf{(y-\mu)'\Sigma^{-1}(y-\mu)} ) \]

\(\mathbf{y} \sim N_p(\mu, \mathbf{\Sigma})\)

22.0.1 Properties of MVN

Let \(\mathbf{A}_{r \times p}\) be a fixed matrix. Then \(\mathbf{Ay} \sim N_r (\mathbf{A \mu, A \Sigma A'})\) . \(r \le p\) and all rows of \(\mathbf{A}\) must be linearly independent to guarantee that \(\mathbf{A \Sigma A}'\) is non-singular.

Let \(\mathbf{G}\) be a matrix such that \(\mathbf{\Sigma}^{-1} = \mathbf{GG}'\). Then \(\mathbf{G'y} \sim N_p(\mathbf{G' \mu, I})\) and \(\mathbf{G'(y-\mu)} \sim N_p (0,\mathbf{I})\)

Any fixed linear combination of \(y_1,...,y_p\) (say \(\mathbf{c'y}\)) follows \(\mathbf{c'y} \sim N_1 (\mathbf{c' \mu, c' \Sigma c})\)

-

Define a partition, \([\mathbf{y}'_1,\mathbf{y}_2']'\) where

\(\mathbf{y}_1\) is \(p_1 \times 1\)

\(\mathbf{y}_2\) is \(p_2 \times 1\),

\(p_1 + p_2 = p\)

\(p_1,p_2 \ge 1\) Then

\[ \left( \begin{array} {c} \mathbf{y}_1 \\ \mathbf{y}_2 \\ \end{array} \right) \sim N \left( \left( \begin{array} {c} \mu_1 \\ \mu_2 \\ \end{array} \right), \left( \begin{array} {cc} \mathbf{\Sigma}_{11} & \mathbf{\Sigma}_{12} \\ \mathbf{\Sigma}_{21} & \mathbf{\Sigma}_{22}\\ \end{array} \right) \right) \]

The marginal distributions of \(\mathbf{y}_1\) and \(\mathbf{y}_2\) are \(\mathbf{y}_1 \sim N_{p1}(\mathbf{\mu_1, \Sigma_{11}})\) and \(\mathbf{y}_2 \sim N_{p2}(\mathbf{\mu_2, \Sigma_{22}})\)

Individual components \(y_1,...,y_p\) are all normally distributed \(y_i \sim N_1(\mu_i, \sigma_{ii})\)

-

The conditional distribution of \(\mathbf{y}_1\) and \(\mathbf{y}_2\) is normal

-

\(\mathbf{y}_1 | \mathbf{y}_2 \sim N_{p1}(\mathbf{\mu_1 + \Sigma_{12} \Sigma_{22}^{-1}(y_2 - \mu_2),\Sigma_{11} - \Sigma_{12} \Sigma_{22}^{-1} \sigma_{21}})\)

- In this formula, we see if we know (have info about) \(\mathbf{y}_2\), we can re-weight \(\mathbf{y}_1\) ’s mean, and the variance is reduced because we know more about \(\mathbf{y}_1\) because we know \(\mathbf{y}_2\)

which is analogous to \(\mathbf{y}_2 | \mathbf{y}_1\). And \(\mathbf{y}_1\) and \(\mathbf{y}_2\) are independently distrusted only if \(\mathbf{\Sigma}_{12} = 0\)

-

If \(\mathbf{y} \sim N(\mathbf{\mu, \Sigma})\) and \(\mathbf{\Sigma}\) is positive definite, then \(\mathbf{(y-\mu)' \Sigma^{-1} (y - \mu)} \sim \chi^2_{(p)}\)

If \(\mathbf{y}_i\) are independent \(N_p (\mathbf{\mu}_i , \mathbf{\Sigma}_i)\) random variables, then for fixed matrices \(\mathbf{A}_{i(m \times p)}\), \(\sum_{i=1}^k \mathbf{A}_i \mathbf{y}_i \sim N_m (\sum_{i=1}^{k} \mathbf{A}_i \mathbf{\mu}_i, \sum_{i=1}^k \mathbf{A}_i \mathbf{\Sigma}_i \mathbf{A}_i)\)

Multiple Regression

\[ \left( \begin{array} {c} Y \\ \mathbf{x} \end{array} \right) \sim N_{p+1} \left( \left[ \begin{array} {c} \mu_y \\ \mathbf{\mu}_x \end{array} \right] , \left[ \begin{array} {cc} \sigma^2_Y & \mathbf{\Sigma}_{yx} \\ \mathbf{\Sigma}_{yx} & \mathbf{\Sigma}_{xx} \end{array} \right] \right) \]

The conditional distribution of Y given x follows a univariate normal distribution with

\[ \begin{aligned} E(Y| \mathbf{x}) &= \mu_y + \mathbf{\Sigma}_{yx} \Sigma_{xx}^{-1} (\mathbf{x}- \mu_x) \\ &= \mu_y - \Sigma_{yx} \Sigma_{xx}^{-1}\mu_x + \Sigma_{yx} \Sigma_{xx}^{-1}\mathbf{x} \\ &= \beta_0 + \mathbf{\beta'x} \end{aligned} \]

where \(\beta = (\beta_1,...,\beta_p)' = \mathbf{\Sigma}_{xx}^{-1} \mathbf{\Sigma}_{yx}'\) (e.g., analogous to \(\mathbf{(x'x)^{-1}x'y}\) but not the same if we consider \(Y_i\) and \(\mathbf{x}_i\), \(i = 1,..,n\) and use the empirical covariance formula: \(var(Y|\mathbf{x}) = \sigma^2_Y - \mathbf{\Sigma_{yx}\Sigma^{-1}_{xx} \Sigma'_{yx}}\))

Samples from Multivariate Normal Populations

A random sample of size n, \(\mathbf{y}_1,.., \mathbf{y}_n\) from \(N_p (\mathbf{\mu}, \mathbf{\Sigma})\). Then

Since \(\mathbf{y}_1,..., \mathbf{y}_n\) are iid, their sample mean, \(\bar{\mathbf{y}} = \sum_{i=1}^n \mathbf{y}_i/n \sim N_p (\mathbf{\mu}, \mathbf{\Sigma}/n)\). that is, \(\bar{\mathbf{y}}\) is an unbiased estimator of \(\mathbf{\mu}\)

-

The \(p \times p\) sample variance-covariance matrix, \(\mathbf{S}\) is \(\mathbf{S} = \frac{1}{n-1}\sum_{i=1}^n (\mathbf{y}_i - \bar{\mathbf{y}})(\mathbf{y}_i - \bar{\mathbf{y}})' = \frac{1}{n-1} (\sum_{i=1}^n \mathbf{y}_i \mathbf{y}_i' - n \bar{\mathbf{y}}\bar{\mathbf{y}}')\)

- where \(\mathbf{S}\) is symmetric, unbiased estimator of \(\mathbf{\Sigma}\) and has \(p(p+1)/2\) random variables.

\((n-1)\mathbf{S} \sim W_p (n-1, \mathbf{\Sigma})\) is a Wishart distribution with n-1 degrees of freedom and expectation \((n-1) \mathbf{\Sigma}\). The Wishart distribution is a multivariate extension of the Chi-squared distribution.

\(\bar{\mathbf{y}}\) and \(\mathbf{S}\) are independent

\(\bar{\mathbf{y}}\) and \(\mathbf{S}\) are sufficient statistics. (All of the info in the data about \(\mathbf{\mu}\) and \(\mathbf{\Sigma}\) is contained in \(\bar{\mathbf{y}}\) and \(\mathbf{S}\) , regardless of sample size).

Large Sample Properties

\(\mathbf{y}_1,..., \mathbf{y}_n\) are a random sample from some population with mean \(\mathbf{\mu}\) and variance-covariance matrix \(\mathbf{\Sigma}\)

\(\bar{\mathbf{y}}\) is a consistent estimator for \(\mu\)

\(\mathbf{S}\) is a consistent estimator for \(\mathbf{\Sigma}\)

Multivariate Central Limit Theorem: Similar to the univariate case, \(\sqrt{n}(\bar{\mathbf{y}} - \mu) \dot{\sim} N_p (\mathbf{0,\Sigma})\) where n is large relative to p (\(n \ge 25p\)), which is equivalent to \(\bar{\mathbf{y}} \dot{\sim} N_p (\mu, \mathbf{\Sigma}/n)\)

Wald’s Theorem: \(n(\bar{\mathbf{y}} - \mu)' \mathbf{S}^{-1} (\bar{\mathbf{y}} - \mu)\) when n is large relative to p.

Maximum Likelihood Estimation for MVN

Suppose iid \(\mathbf{y}_1 ,... \mathbf{y}_n \sim N_p (\mu, \mathbf{\Sigma})\), the likelihood function for the data is

\[ \begin{aligned} L(\mu, \mathbf{\Sigma}) &= \prod_{j=1}^n (\frac{1}{(2\pi)^{p/2}|\mathbf{\Sigma}|^{1/2}} \exp(-\frac{1}{2}(\mathbf{y}_j -\mu)'\mathbf{\Sigma}^{-1})(\mathbf{y}_j -\mu)) \\ &= \frac{1}{(2\pi)^{np/2}|\mathbf{\Sigma}|^{n/2}} \exp(-\frac{1}{2} \sum_{j=1}^n(\mathbf{y}_j -\mu)'\mathbf{\Sigma}^{-1})(\mathbf{y}_j -\mu) \end{aligned} \]

Then, the MLEs are

\[ \hat{\mu} = \bar{\mathbf{y}} \]

\[ \hat{\mathbf{\Sigma}} = \frac{n-1}{n} \mathbf{S} \]

using derivatives of the log of the likelihood function with respect to \(\mu\) and \(\mathbf{\Sigma}\)

Properties of MLEs

Invariance: If \(\hat{\theta}\) is the MLE of \(\theta\), then the MLE of \(h(\theta)\) is \(h(\hat{\theta})\) for any function h(.)

Consistency: MLEs are consistent estimators, but they are usually biased

Efficiency: MLEs are efficient estimators (no other estimator has a smaller variance for large samples)

-

Asymptotic normality: Suppose that \(\hat{\theta}_n\) is the MLE for \(\theta\) based upon n independent observations. Then \(\hat{\theta}_n \dot{\sim} N(\theta, \mathbf{H}^{-1})\)

\(\mathbf{H}\) is the Fisher Information Matrix, which contains the expected values of the second partial derivatives fo the log-likelihood function. the (i,j)th element of \(\mathbf{H}\) is \(-E(\frac{\partial^2 l(\mathbf{\theta})}{\partial \theta_i \partial \theta_j})\)

we can estimate \(\mathbf{H}\) by finding the form determined above, and evaluate it at \(\theta = \hat{\theta}_n\)

-

Likelihood ratio testing: for some null hypothesis, \(H_0\) we can form a likelihood ratio test

The statistic is: \(\Lambda = \frac{\max_{H_0}l(\mathbf{\mu}, \mathbf{\Sigma|Y})}{\max l(\mu, \mathbf{\Sigma | Y})}\)

For large n, \(-2 \log \Lambda \sim \chi^2_{(v)}\) where v is the number of parameters in the unrestricted space minus the number of parameters under \(H_0\)

Test of Multivariate Normality

-

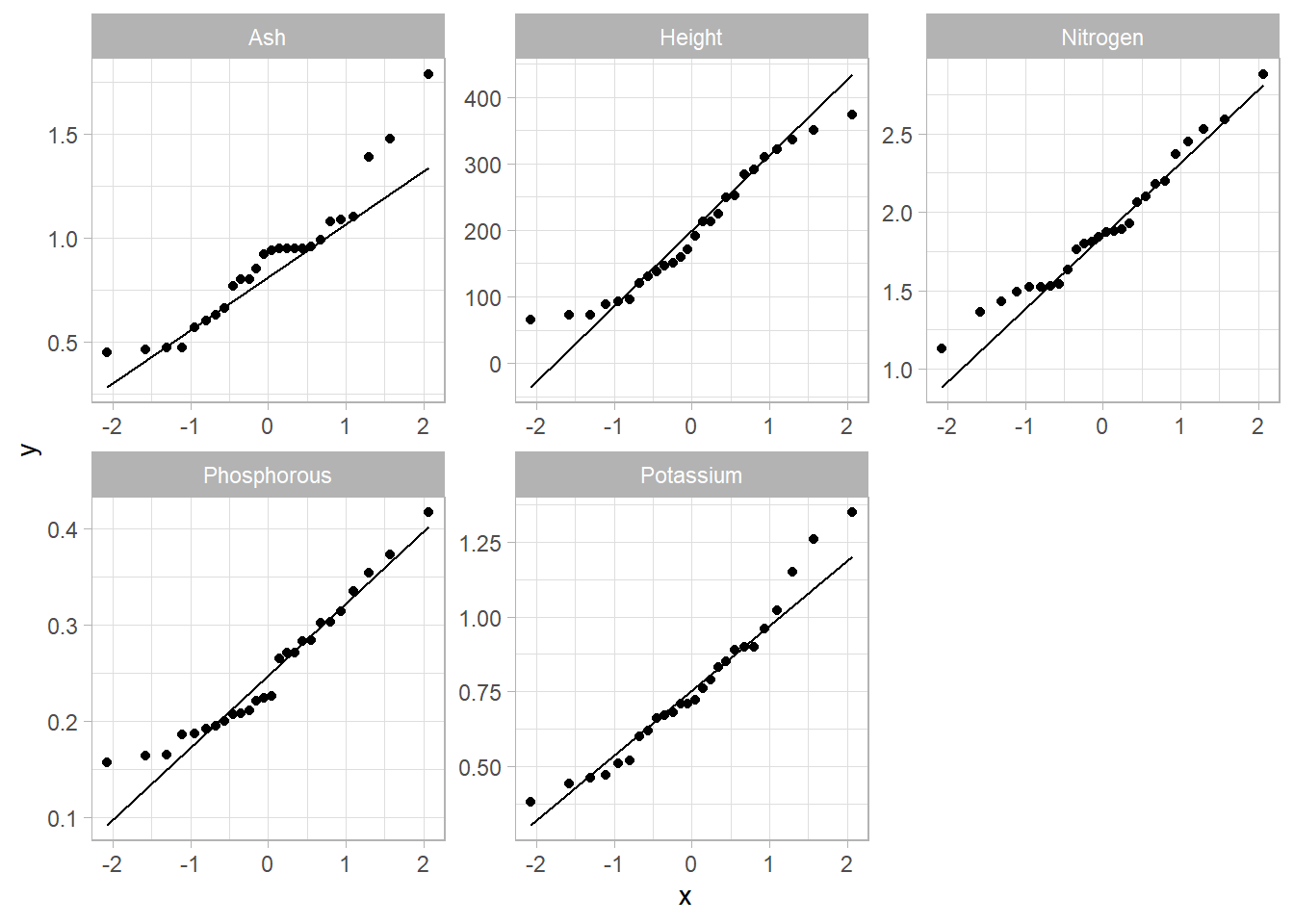

Check univariate normality for each trait (X) separately

Can check \[Normality Assessment\]

The good thing is that if any of the univariate trait is not normal, then the joint distribution is not normal (see again [m]). If a joint multivariate distribution is normal, then the marginal distribution has to be normal.

However, marginal normality of all traits does not imply joint MVN

Easily rule out multivariate normality, but not easy to prove it

-

Mardia’s tests for multivariate normality

Multivariate skewness is\[ \beta_{1,p} = E[(\mathbf{y}- \mathbf{\mu})' \mathbf{\Sigma}^{-1} (\mathbf{x} - \mathbf{\mu})]^3 \]

where \(\mathbf{x}\) and \(\mathbf{y}\) are independent, but have the same distribution (note: \(\beta\) here is not regression coefficient)

Multivariate kurtosis is defined as

\[ \beta_{2,p} - E[(\mathbf{y}- \mathbf{\mu})' \mathbf{\Sigma}^{-1} (\mathbf{x} - \mathbf{\mu})]^2 \]

For the MVN distribution, we have \(\beta_{1,p} = 0\) and \(\beta_{2,p} = p(p+2)\)

-

For a sample of size n, we can estimate

\[ \hat{\beta}_{1,p} = \frac{1}{n^2}\sum_{i=1}^n \sum_{j=1}^n g^2_{ij} \]

\[ \hat{\beta}_{2,p} = \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^n g^2_{ii} \]

- where \(g_{ij} = (\mathbf{y}_i - \bar{\mathbf{y}})' \mathbf{S}^{-1} (\mathbf{y}_j - \bar{\mathbf{y}})\). Note: \(g_{ii} = d^2_i\) where \(d^2_i\) is the Mahalanobis distance

-

(Mardia 1970) shows for large n

\[ \kappa_1 = \frac{n \hat{\beta}_{1,p}}{6} \dot{\sim} \chi^2_{p(p+1)(p+2)/6} \]

\[ \kappa_2 = \frac{\hat{\beta}_{2,p} - p(p+2)}{\sqrt{8p(p+2)/n}} \sim N(0,1) \]

Hence, we can use \(\kappa_1\) and \(\kappa_2\) to test the null hypothesis of MVN.

When the data are non-normal, normal theory tests on the mean are sensitive to \(\beta_{1,p}\) , while tests on the covariance are sensitive to \(\beta_{2,p}\)

Alternatively, Doornik-Hansen test for multivariate normality (Doornik and Hansen 2008)

-

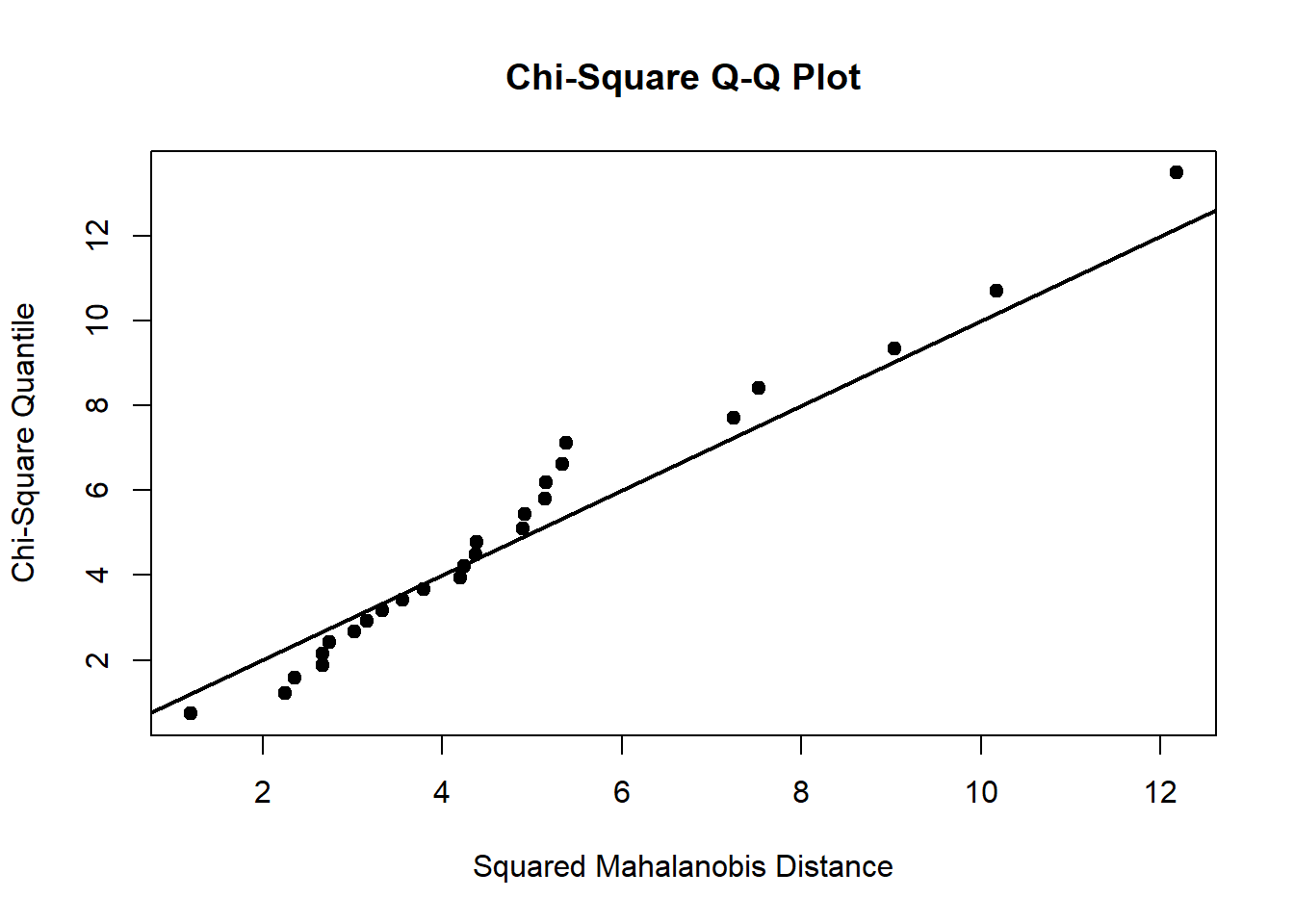

Chi-square Q-Q plot

Let \(\mathbf{y}_i, i = 1,...,n\) be a random sample sample from \(N_p(\mathbf{\mu}, \mathbf{\Sigma})\)

Then \(\mathbf{z}_i = \mathbf{\Sigma}^{-1/2}(\mathbf{y}_i - \mathbf{\mu}), i = 1,...,n\) are iid \(N_p (\mathbf{0}, \mathbf{I})\). Thus, \(d_i^2 = \mathbf{z}_i' \mathbf{z}_i \sim \chi^2_p , i = 1,...,n\)

plot the ordered \(d_i^2\) values against the qualities of the \(\chi^2_p\) distribution. When normality holds, the plot should approximately resemble a straight lien passing through the origin at a 45 degree

it requires large sample size (i.e., sensitive to sample size). Even if we generate data from a MVN, the tail of the Chi-square Q-Q plot can still be out of line.

-

If the data are not normal, we can

ignore it

use nonparametric methods

use models based upon an approximate distribution (e.g., GLMM)

try performing a transformation

library(heplots)

library(ICSNP)

library(MVN)

library(tidyverse)

trees = read.table("images/trees.dat")

names(trees) <- c("Nitrogen","Phosphorous","Potassium","Ash","Height")

str(trees)

#> 'data.frame': 26 obs. of 5 variables:

#> $ Nitrogen : num 2.2 2.1 1.52 2.88 2.18 1.87 1.52 2.37 2.06 1.84 ...

#> $ Phosphorous: num 0.417 0.354 0.208 0.335 0.314 0.271 0.164 0.302 0.373 0.265 ...

#> $ Potassium : num 1.35 0.9 0.71 0.9 1.26 1.15 0.83 0.89 0.79 0.72 ...

#> $ Ash : num 1.79 1.08 0.47 1.48 1.09 0.99 0.85 0.94 0.8 0.77 ...

#> $ Height : int 351 249 171 373 321 191 225 291 284 213 ...

summary(trees)

#> Nitrogen Phosphorous Potassium Ash

#> Min. :1.130 Min. :0.1570 Min. :0.3800 Min. :0.4500

#> 1st Qu.:1.532 1st Qu.:0.1963 1st Qu.:0.6050 1st Qu.:0.6375

#> Median :1.855 Median :0.2250 Median :0.7150 Median :0.9300

#> Mean :1.896 Mean :0.2506 Mean :0.7619 Mean :0.8873

#> 3rd Qu.:2.160 3rd Qu.:0.2975 3rd Qu.:0.8975 3rd Qu.:0.9825

#> Max. :2.880 Max. :0.4170 Max. :1.3500 Max. :1.7900

#> Height

#> Min. : 65.0

#> 1st Qu.:122.5

#> Median :181.0

#> Mean :196.6

#> 3rd Qu.:276.0

#> Max. :373.0

cor(trees, method = "pearson") # correlation matrix

#> Nitrogen Phosphorous Potassium Ash Height

#> Nitrogen 1.0000000 0.6023902 0.5462456 0.6509771 0.8181641

#> Phosphorous 0.6023902 1.0000000 0.7037469 0.6707871 0.7739656

#> Potassium 0.5462456 0.7037469 1.0000000 0.6710548 0.7915683

#> Ash 0.6509771 0.6707871 0.6710548 1.0000000 0.7676771

#> Height 0.8181641 0.7739656 0.7915683 0.7676771 1.0000000

# qq-plot

gg <- trees %>%

pivot_longer(everything(), names_to = "Var", values_to = "Value") %>%

ggplot(aes(sample = Value)) +

geom_qq() +

geom_qq_line() +

facet_wrap("Var", scales = "free")

gg

# Univariate normality

sw_tests <- apply(trees, MARGIN = 2, FUN = shapiro.test)

sw_tests

#> $Nitrogen

#>

#> Shapiro-Wilk normality test

#>

#> data: newX[, i]

#> W = 0.96829, p-value = 0.5794

#>

#>

#> $Phosphorous

#>

#> Shapiro-Wilk normality test

#>

#> data: newX[, i]

#> W = 0.93644, p-value = 0.1104

#>

#>

#> $Potassium

#>

#> Shapiro-Wilk normality test

#>

#> data: newX[, i]

#> W = 0.95709, p-value = 0.3375

#>

#>

#> $Ash

#>

#> Shapiro-Wilk normality test

#>

#> data: newX[, i]

#> W = 0.92071, p-value = 0.04671

#>

#>

#> $Height

#>

#> Shapiro-Wilk normality test

#>

#> data: newX[, i]

#> W = 0.94107, p-value = 0.1424

# Kolmogorov-Smirnov test

ks_tests <- map(trees, ~ ks.test(scale(.x),"pnorm"))

ks_tests

#> $Nitrogen

#>

#> Asymptotic one-sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov test

#>

#> data: scale(.x)

#> D = 0.12182, p-value = 0.8351

#> alternative hypothesis: two-sided

#>

#>

#> $Phosphorous

#>

#> Asymptotic one-sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov test

#>

#> data: scale(.x)

#> D = 0.17627, p-value = 0.3944

#> alternative hypothesis: two-sided

#>

#>

#> $Potassium

#>

#> Asymptotic one-sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov test

#>

#> data: scale(.x)

#> D = 0.10542, p-value = 0.9348

#> alternative hypothesis: two-sided

#>

#>

#> $Ash

#>

#> Asymptotic one-sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov test

#>

#> data: scale(.x)

#> D = 0.14503, p-value = 0.6449

#> alternative hypothesis: two-sided

#>

#>

#> $Height

#>

#> Asymptotic one-sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov test

#>

#> data: scale(.x)

#> D = 0.1107, p-value = 0.9076

#> alternative hypothesis: two-sided

# Mardia's test, need large sample size for power

mardia_test <-

mvn(

trees,

mvnTest = "mardia",

covariance = FALSE,

multivariatePlot = "qq"

)

mardia_test$multivariateNormality

#> Test Statistic p value Result

#> 1 Mardia Skewness 29.7248528871795 0.72054426745778 YES

#> 2 Mardia Kurtosis -1.67743173185383 0.0934580886477281 YES

#> 3 MVN <NA> <NA> YES

# Doornik-Hansen's test

dh_test <-

mvn(

trees,

mvnTest = "dh",

covariance = FALSE,

multivariatePlot = "qq"

)

dh_test$multivariateNormality

#> Test E df p value MVN

#> 1 Doornik-Hansen 161.9446 10 1.285352e-29 NO

# Henze-Zirkler's test

hz_test <-

mvn(

trees,

mvnTest = "hz",

covariance = FALSE,

multivariatePlot = "qq"

)

hz_test$multivariateNormality

#> Test HZ p value MVN

#> 1 Henze-Zirkler 0.7591525 0.6398905 YES

# The last column indicates whether dataset follows a multivariate normality or not (i.e, YES or NO) at significance level 0.05.

# Royston's test

# can only apply for 3 < obs < 5000 (because of Shapiro-Wilk's test)

royston_test <-

mvn(

trees,

mvnTest = "royston",

covariance = FALSE,

multivariatePlot = "qq"

)

royston_test$multivariateNormality

#> Test H p value MVN

#> 1 Royston 9.064631 0.08199215 YES

# E-statistic

estat_test <-

mvn(

trees,

mvnTest = "energy",

covariance = FALSE,

multivariatePlot = "qq"

)

estat_test$multivariateNormality

#> Test Statistic p value MVN

#> 1 E-statistic 1.091101 0.532 YES22.0.2 Mean Vector Inference

In the univariate normal distribution, we test \(H_0: \mu =\mu_0\) by using

\[ T = \frac{\bar{y}- \mu_0}{s/\sqrt{n}} \sim t_{n-1} \]

under the null hypothesis. And reject the null if \(|T|\) is large relative to \(t_{(1-\alpha/2,n-1)}\) because it means that seeing a value as large as what we observed is rare if the null is true

Equivalently,

\[ T^2 = \frac{(\bar{y}- \mu_0)^2}{s^2/n} = n(\bar{y}- \mu_0)(s^2)^{-1}(\bar{y}- \mu_0) \sim f_{(1,n-1)} \]

22.0.2.1 Natural Multivariate Generalization

\[ \begin{aligned} &H_0: \mathbf{\mu} = \mathbf{\mu}_0 \\ &H_a: \mathbf{\mu} \neq \mathbf{\mu}_0 \end{aligned} \]

Define Hotelling’s \(T^2\) by

\[ T^2 = n(\bar{\mathbf{y}} - \mathbf{\mu}_0)'\mathbf{S}^{-1}(\bar{\mathbf{y}} - \mathbf{\mu}_0) \]

which can be viewed as a generalized distance between \(\bar{\mathbf{y}}\) and \(\mathbf{\mu}_0\)

Under the assumption of normality,

\[ F = \frac{n-p}{(n-1)p} T^2 \sim f_{(p,n-p)} \]

and reject the null hypothesis when \(F > f_{(1-\alpha, p, n-p)}\)

-

The \(T^2\) test is invariant to changes in measurement units.

- If \(\mathbf{z = Cy + d}\) where \(\mathbf{C}\) and \(\mathbf{d}\) do not depend on \(\mathbf{y}\), then \(T^2(\mathbf{z}) - T^2(\mathbf{y})\)

The \(T^2\) test can be derived as a likelihood ratio test of \(H_0: \mu = \mu_0\)

22.0.2.2 Confidence Intervals

22.0.2.2.1 Confidence Region

An “exact” \(100(1-\alpha)\%\) confidence region for \(\mathbf{\mu}\) is the set of all vectors, \(\mathbf{v}\), which are “close enough” to the observed mean vector, \(\bar{\mathbf{y}}\) to satisfy

\[ n(\bar{\mathbf{y}} - \mathbf{\mu}_0)'\mathbf{S}^{-1}(\bar{\mathbf{y}} - \mathbf{\mu}_0) \le \frac{(n-1)p}{n-p} f_{(1-\alpha, p, n-p)} \]

- \(\mathbf{v}\) are just the mean vectors that are not rejected by the \(T^2\) test when \(\mathbf{\bar{y}}\) is observed.

In case that you have 2 parameters, the confidence region is a “hyper-ellipsoid”.

In this region, it consists of all \(\mathbf{\mu}_0\) vectors for which the \(T^2\) test would not reject \(H_0\) at significance level \(\alpha\)

Even though the confidence region better assesses the joint knowledge concerning plausible values of \(\mathbf{\mu}\) , people typically include confidence statement about the individual component means. We’d like all of the separate confidence statements to hold simultaneously with a specified high probability. Simultaneous confidence intervals: intervals against any statement being incorrect

22.0.2.2.1.1 Simultaneous Confidence Statements

- Intervals based on a rectangular confidence region by projecting the previous region onto the coordinate axes:

\[ \bar{y}_{i} \pm \sqrt{\frac{(n-1)p}{n-p}f_{(1-\alpha, p,n-p)}\frac{s_{ii}}{n}} \]

for all \(i = 1,..,p\)

which implied confidence region is conservative; it has at least \(100(1- \alpha)\%\)

Generally, simultaneous \(100(1-\alpha) \%\) confidence intervals for all linear combinations , \(\mathbf{a}\) of the elements of the mean vector are given by

\[ \mathbf{a'\bar{y}} \pm \sqrt{\frac{(n-1)p}{n-p}f_{(1-\alpha, p,n-p)}\frac{\mathbf{a'Sa}}{n}} \]

works for any arbitrary linear combination \(\mathbf{a'\mu} = a_1 \mu_1 + ... + a_p \mu_p\), which is a projection onto the axis in the direction of \(\mathbf{a}\)

These intervals have the property that the probability that at least one such interval does not contain the appropriate \(\mathbf{a' \mu}\) is no more than \(\alpha\)

These types of intervals can be used for “data snooping” (like \[Scheffe\])

22.0.2.2.1.2 One \(\mu\) at a time

- One at a time confidence intervals:

\[ \bar{y}_i \pm t_{(1 - \alpha/2, n-1} \sqrt{\frac{s_{ii}}{n}} \]

Each of these intervals has a probability of \(1-\alpha\) of covering the appropriate \(\mu_i\)

But they ignore the covariance structure of the \(p\) variables

If we only care about \(k\) simultaneous intervals, we can use “one at a time” method with the \[Bonferroni\] correction.

This method gets more conservative as the number of intervals \(k\) increases.

22.0.3 General Hypothesis Testing

22.0.3.1 One-sample Tests

\[ H_0: \mathbf{C \mu= 0} \]

where

- \(\mathbf{C}\) is a \(c \times p\) matrix of rank c where \(c \le p\)

We can test this hypothesis using the following statistic

\[ F = \frac{n - c}{(n-1)c} T^2 \]

where \(T^2 = n(\mathbf{C\bar{y}})' (\mathbf{CSC'})^{-1} (\mathbf{C\bar{y}})\)

Example:

\[ H_0: \mu_1 = \mu_2 = ... = \mu_p \]

Equivalently,

\[ \begin{aligned} \mu_1 - \mu_2 &= 0 \\ &\vdots \\ \mu_{p-1} - \mu_p &= 0 \end{aligned} \]

a total of \(p-1\) tests. Hence, we have \(\mathbf{C}\) as the \(p - 1 \times p\) matrix

\[ \mathbf{C} = \left( \begin{array} {ccccc} 1 & -1 & 0 & \ldots & 0 \\ 0 & 1 & -1 & \ldots & 0 \\ \vdots & \vdots & \vdots & \ddots & \vdots \\ 0 & 0 & \ldots & 1 & -1 \end{array} \right) \]

number of rows = \(c = p -1\)

Equivalently, we can also compare all of the other means to the first mean. Then, we test \(\mu_1 - \mu_2 = 0, \mu_1 - \mu_3 = 0,..., \mu_1 - \mu_p = 0\), the \((p-1) \times p\) matrix \(\mathbf{C}\) is

\[ \mathbf{C} = \left( \begin{array} {ccccc} -1 & 1 & 0 & \ldots & 0 \\ -1 & 0 & 1 & \ldots & 0 \\ \vdots & \vdots & \vdots & \ddots & \vdots \\ -1 & 0 & \ldots & 0 & 1 \end{array} \right) \]

The value of \(T^2\) is invariant to these equivalent choices of \(\mathbf{C}\)

This is often used for repeated measures designs, where each subject receives each treatment once over successive periods of time (all treatments are administered to each unit).

Example:

Let \(y_{ij}\) be the response from subject i at time j for \(i = 1,..,n, j = 1,...,T\). In this case, \(\mathbf{y}_i = (y_{i1}, ..., y_{iT})', i = 1,...,n\) are a random sample from \(N_T (\mathbf{\mu}, \mathbf{\Sigma})\)

Let \(n=8\) subjects, \(T = 6\). We are interested in \(\mu_1, .., \mu_6\)

\[ H_0: \mu_1 = \mu_2 = ... = \mu_6 \]

Equivalently,

\[ \begin{aligned} \mu_1 - \mu_2 &= 0 \\ \mu_2 - \mu_3 &= 0 \\ &... \\ \mu_5 - \mu_6 &= 0 \end{aligned} \]

We can test orthogonal polynomials for 4 equally spaced time points. To test for example the null hypothesis that quadratic and cubic effects are jointly equal to 0, we would define \(\mathbf{C}\)

\[ \mathbf{C} = \left( \begin{array} {cccc} 1 & -1 & -1 & 1 \\ -1 & 3 & -3 & 1 \end{array} \right) \]

22.0.3.2 Two-Sample Tests

Consider the analogous two sample multivariate tests.

Example: we have data on two independent random samples, one sample from each of two populations

\[ \begin{aligned} \mathbf{y}_{1i} &\sim N_p (\mathbf{\mu_1, \Sigma}) \\ \mathbf{y}_{2j} &\sim N_p (\mathbf{\mu_2, \Sigma}) \end{aligned} \]

We assume

normality

equal variance-covariance matrices

independent random samples

We can summarize our data using the sufficient statistics \(\mathbf{\bar{y}}_1, \mathbf{S}_1, \mathbf{\bar{y}}_2, \mathbf{S}_2\) with respective sample sizes, \(n_1,n_2\)

Since we assume that \(\mathbf{\Sigma}_1 = \mathbf{\Sigma}_2 = \mathbf{\Sigma}\), compute a pooled estimate of the variance-covariance matrix on \(n_1 + n_2 - 2\) df

\[ \mathbf{S} = \frac{(n_1 - 1)\mathbf{S}_1 + (n_2-1) \mathbf{S}_2}{(n_1 -1) + (n_2 - 1)} \]

\[ \begin{aligned} &H_0: \mathbf{\mu}_1 = \mathbf{\mu}_2 \\ &H_a: \mathbf{\mu}_1 \neq \mathbf{\mu}_2 \end{aligned} \]

At least one element of the mean vectors is different

We use

\(\mathbf{\bar{y}}_1 - \mathbf{\bar{y}}_2\) to estimate \(\mu_1 - \mu_2\)

-

\(\mathbf{S}\) to estimate \(\mathbf{\Sigma}\)

Note: because we assume the two populations are independent, there is no covariance

\(cov(\mathbf{\bar{y}}_1 - \mathbf{\bar{y}}_2) = var(\mathbf{\bar{y}}_1) + var(\mathbf{\bar{y}}_2) = \frac{\mathbf{\Sigma_1}}{n_1} + \frac{\mathbf{\Sigma_2}}{n_2} = \mathbf{\Sigma}(\frac{1}{n_1} + \frac{1}{n_2})\)

Reject \(H_0\) if

\[ \begin{aligned} T^2 &= (\mathbf{\bar{y}}_1 - \mathbf{\bar{y}}_2)'\{ \mathbf{S} (\frac{1}{n_1} + \frac{1}{n_2})\}^{-1} (\mathbf{\bar{y}}_1 - \mathbf{\bar{y}}_2)\\ &= \frac{n_1 n_2}{n_1 +n_2} (\mathbf{\bar{y}}_1 - \mathbf{\bar{y}}_2)'\{ \mathbf{S} \}^{-1} (\mathbf{\bar{y}}_1 - \mathbf{\bar{y}}_2)\\ & \ge \frac{(n_1 + n_2 -2)p}{n_1 + n_2 - p - 1} f_{(1- \alpha,n_1 + n_2 - p -1)} \end{aligned} \]

or equivalently, if

\[ F = \frac{n_1 + n_2 - p -1}{(n_1 + n_2 -2)p} T^2 \ge f_{(1- \alpha, p , n_1 + n_2 -p -1)} \]

A \(100(1-\alpha) \%\) confidence region for \(\mu_1 - \mu_2\) consists of all vector \(\delta\) which satisfy

\[ \frac{n_1 n_2}{n_1 + n_2} (\mathbf{\bar{y}}_1 - \mathbf{\bar{y}}_2 - \mathbf{\delta})' \mathbf{S}^{-1}(\mathbf{\bar{y}}_1 - \mathbf{\bar{y}}_2 - \mathbf{\delta}) \le \frac{(n_1 + n_2 - 2)p}{n_1 + n_2 -p - 1}f_{(1-\alpha, p , n_1 + n_2 - p -1)} \]

The simultaneous confidence intervals for all linear combinations of \(\mu_1 - \mu_2\) have the form

\[ \mathbf{a'}(\mathbf{\bar{y}}_1 - \mathbf{\bar{y}}_2) \pm \sqrt{\frac{(n_1 + n_2 -2)p}{n_1 + n_2 - p -1}}f_{(1-\alpha, p, n_1 + n_2 -p -1)} \times \sqrt{\mathbf{a'Sa}(\frac{1}{n_1} + \frac{1}{n_2})} \]

Bonferroni intervals, for k combinations

\[ (\bar{y}_{1i} - \bar{y}_{2i}) \pm t_{(1-\alpha/2k, n_1 + n_2 - 2)}\sqrt{(\frac{1}{n_1} + \frac{1}{n_2})s_{ii}} \]

22.0.3.3 Model Assumptions

If model assumption are not met

-

Unequal Covariance Matrices

If \(n_1 = n_2\) (large samples) there is little effect on the Type I error rate and power fo the two sample test

If \(n_1 > n_2\) and the eigenvalues of \(\mathbf{\Sigma}_1 \mathbf{\Sigma}^{-1}_2\) are less than 1, the Type I error level is inflated

If \(n_1 > n_2\) and some eigenvalues of \(\mathbf{\Sigma}_1 \mathbf{\Sigma}_2^{-1}\) are greater than 1, the Type I error rate is too small, leading to a reduction in power

-

Sample Not Normal

Type I error level of the two sample \(T^2\) test isn’t much affect by moderate departures from normality if the two populations being sampled have similar distributions

One sample \(T^2\) test is much more sensitive to lack of normality, especially when the distribution is skewed.

Intuitively, you can think that in one sample your distribution will be sensitive, but the distribution of the difference between two similar distributions will not be as sensitive.

-

Solutions:

Transform to make the data more normal

-

Large large samples, use the \(\chi^2\) (Wald) test, in which populations don’t need to be normal, or equal sample sizes, or equal variance-covariance matrices

- \(H_0: \mu_1 - \mu_2 =0\) use \((\mathbf{\bar{y}}_1 - \mathbf{\bar{y}}_2)'( \frac{1}{n_1} \mathbf{S}_1 + \frac{1}{n_2}\mathbf{S}_2)^{-1}(\mathbf{\bar{y}}_1 - \mathbf{\bar{y}}_2) \dot{\sim} \chi^2_{(p)}\)

22.0.3.3.1 Equal Covariance Matrices Tests

With independent random samples from k populations of \(p\)-dimensional vectors. We compute the sample covariance matrix for each, \(\mathbf{S}_i\), where \(i = 1,...,k\)

\[ \begin{aligned} &H_0: \mathbf{\Sigma}_1 = \mathbf{\Sigma}_2 = \ldots = \mathbf{\Sigma}_k = \mathbf{\Sigma} \\ &H_a: \text{at least 2 are different} \end{aligned} \]

Assume \(H_0\) is true, we would use a pooled estimate of the common covariance matrix, \(\mathbf{\Sigma}\)

\[ \mathbf{S} = \frac{\sum_{i=1}^k (n_i -1)\mathbf{S}_i}{\sum_{i=1}^k (n_i - 1)} \]

with \(\sum_{i=1}^k (n_i -1)\)

22.0.3.3.1.1 Bartlett’s Test

(a modification of the likelihood ratio test). Define

\[ N = \sum_{i=1}^k n_i \]

and (note: \(| |\) are determinants here, not absolute value)

\[ M = (N - k) \log|\mathbf{S}| - \sum_{i=1}^k (n_i - 1) \log|\mathbf{S}_i| \]

\[ C^{-1} = 1 - \frac{2p^2 + 3p - 1}{6(p+1)(k-1)} \{\sum_{i=1}^k (\frac{1}{n_i - 1}) - \frac{1}{N-k} \} \]

Reject \(H_0\) when \(MC^{-1} > \chi^2_{1- \alpha, (k-1)p(p+1)/2}\)

If not all samples are from normal populations, \(MC^{-1}\) has a distribution which is often shifted to the right of the nominal \(\chi^2\) distribution, which means \(H_0\) is often rejected even when it is true (the Type I error level is inflated). Hence, it is better to test individual normality first, or then multivariate normality before you do Bartlett’s test.

22.0.3.4 Two-Sample Repeated Measurements

Define \(\mathbf{y}_{hi} = (y_{hi1}, ..., y_{hit})'\) to be the observations from the i-th subject in the h-th group for times 1 through T

Assume that \(\mathbf{y}_{11}, ..., \mathbf{y}_{1n_1}\) are iid \(N_t(\mathbf{\mu}_1, \mathbf{\Sigma})\) and that \(\mathbf{y}_{21},...,\mathbf{y}_{2n_2}\) are iid \(N_t(\mathbf{\mu}_2, \mathbf{\Sigma})\)

\(H_0: \mathbf{C}(\mathbf{\mu}_1 - \mathbf{\mu}_2) = \mathbf{0}_c\) where \(\mathbf{C}\) is a \(c \times t\) matrix of rank \(c\) where \(c \le t\)

The test statistic has the form

\[ T^2 = \frac{n_1 n_2}{n_1 + n_2} (\mathbf{\bar{y}}_1 - \mathbf{\bar{y}}_2)' \mathbf{C}'(\mathbf{CSC}')^{-1}\mathbf{C} (\mathbf{\bar{y}}_1 - \mathbf{\bar{y}}_2) \]

where \(\mathbf{S}\) is the pooled covariance estimate. Then,

\[ F = \frac{n_1 + n_2 - c -1}{(n_1 + n_2-2)c} T^2 \sim f_{(c, n_1 + n_2 - c-1)} \]

when \(H_0\) is true

If the null hypothesis \(H_0: \mu_1 = \mu_2\) is rejected. A weaker hypothesis is that the profiles for the two groups are parallel.

\[ \begin{aligned} \mu_{11} - \mu_{21} &= \mu_{12} - \mu_{22} \\ &\vdots \\ \mu_{1t-1} - \mu_{2t-1} &= \mu_{1t} - \mu_{2t} \end{aligned} \]

The null hypothesis matrix term is then

\(H_0: \mathbf{C}(\mu_1 - \mu_2) = \mathbf{0}_c\) , where \(c = t - 1\) and

\[ \mathbf{C} = \left( \begin{array} {ccccc} 1 & -1 & 0 & \ldots & 0 \\ 0 & 1 & -1 & \ldots & 0 \\ \vdots & \vdots & \vdots & \ddots & \vdots \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & \ldots & -1 \end{array} \right)_{(t-1) \times t} \]

# One-sample Hotelling's T^2 test

# Create data frame

plants <- data.frame(

y1 = c(2.11, 2.36, 2.13, 2.78, 2.17),

y2 = c(10.1, 35.0, 2.0, 6.0, 2.0),

y3 = c(3.4, 4.1, 1.9, 3.8, 1.7)

)

# Center the data with

# the hypothesized means and make a matrix

plants_ctr <- plants %>%

transmute(y1_ctr = y1 - 2.85,

y2_ctr = y2 - 15.0,

y3_ctr = y3 - 6.0) %>%

as.matrix()

# Use anova.mlm to calculate Wilks' lambda

onesamp_fit <- anova(lm(plants_ctr ~ 1), test = "Wilks")

onesamp_fit

#> Analysis of Variance Table

#>

#> Df Wilks approx F num Df den Df Pr(>F)

#> (Intercept) 1 0.054219 11.629 3 2 0.08022 .

#> Residuals 4

#> ---

#> Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1can’t reject the null of hypothesized vector of means

# Paired-Sample Hotelling's T^2 test

library(ICSNP)

# Create data frame

waste <- data.frame(

case = 1:11,

com_y1 = c(6, 6, 18, 8, 11, 34, 28, 71, 43, 33, 20),

com_y2 = c(27, 23, 64, 44, 30, 75, 26, 124, 54, 30, 14),

state_y1 = c(25, 28, 36, 35, 15, 44, 42, 54, 34, 29, 39),

state_y2 = c(15, 13, 22, 29, 31, 64, 30, 64, 56, 20, 21)

)

# Calculate the difference between commercial and state labs

waste_diff <- waste %>%

transmute(y1_diff = com_y1 - state_y1,

y2_diff = com_y2 - state_y2)

# Run the test

paired_fit <- HotellingsT2(waste_diff)

# value T.2 in the output corresponds to

# the approximate F-value in the output from anova.mlm

paired_fit

#>

#> Hotelling's one sample T2-test

#>

#> data: waste_diff

#> T.2 = 6.1377, df1 = 2, df2 = 9, p-value = 0.02083

#> alternative hypothesis: true location is not equal to c(0,0)reject the null that the two labs’ measurements are equal

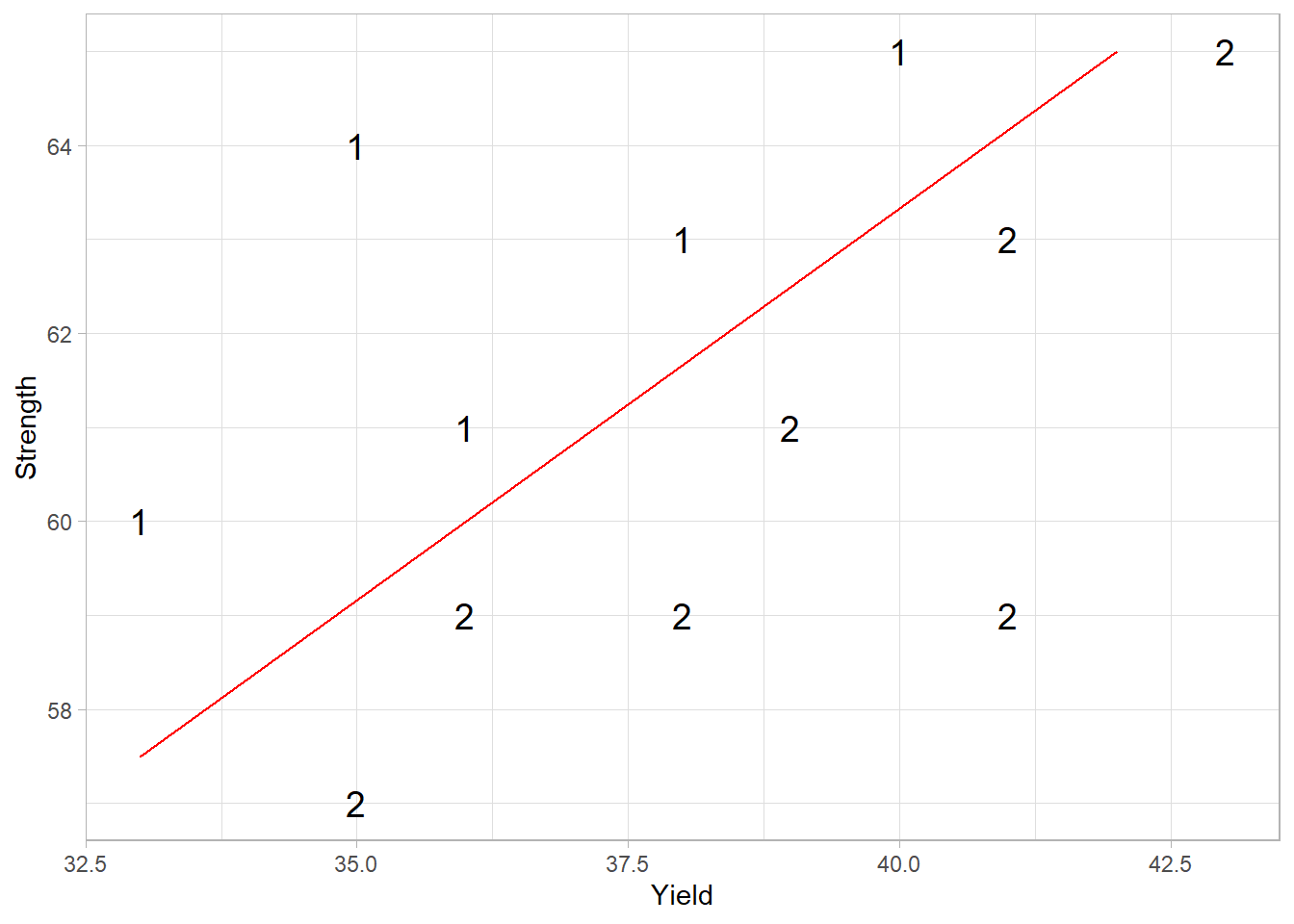

# Independent-Sample Hotelling's T^2 test with Bartlett's test

# Read in data

steel <- read.table("images/steel.dat")

names(steel) <- c("Temp", "Yield", "Strength")

str(steel)

#> 'data.frame': 12 obs. of 3 variables:

#> $ Temp : int 1 1 1 1 1 2 2 2 2 2 ...

#> $ Yield : int 33 36 35 38 40 35 36 38 39 41 ...

#> $ Strength: int 60 61 64 63 65 57 59 59 61 63 ...

# Plot the data

ggplot(steel, aes(x = Yield, y = Strength)) +

geom_text(aes(label = Temp), size = 5) +

geom_segment(aes(

x = 33,

y = 57.5,

xend = 42,

yend = 65

), col = "red")

# Bartlett's test for equality of covariance matrices

# same thing as Box's M test in the multivariate setting

bart_test <- boxM(steel[, -1], steel$Temp)

bart_test # fail to reject the null of equal covariances

#>

#> Box's M-test for Homogeneity of Covariance Matrices

#>

#> data: steel[, -1]

#> Chi-Sq (approx.) = 0.38077, df = 3, p-value = 0.9442

# anova.mlm

twosamp_fit <-

anova(lm(cbind(Yield, Strength) ~ factor(Temp),

data = steel),

test = "Wilks")

twosamp_fit

#> Analysis of Variance Table

#>

#> Df Wilks approx F num Df den Df Pr(>F)

#> (Intercept) 1 0.001177 3818.1 2 9 6.589e-14 ***

#> factor(Temp) 1 0.294883 10.8 2 9 0.004106 **

#> Residuals 10

#> ---

#> Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

# ICSNP package

twosamp_fit2 <-

HotellingsT2(cbind(steel$Yield, steel$Strength) ~

factor(steel$Temp))

twosamp_fit2

#>

#> Hotelling's two sample T2-test

#>

#> data: cbind(steel$Yield, steel$Strength) by factor(steel$Temp)

#> T.2 = 10.76, df1 = 2, df2 = 9, p-value = 0.004106

#> alternative hypothesis: true location difference is not equal to c(0,0)reject null. Hence, there is a difference in the means of the bivariate normal distributions

22.1 MANOVA

Multivariate Analysis of Variance

One-way MANOVA

Compare treatment means for h different populations

Population 1: \(\mathbf{y}_{11}, \mathbf{y}_{12}, \dots, \mathbf{y}_{1n_1} \sim idd N_p (\mathbf{\mu}_1, \mathbf{\Sigma})\)

\(\vdots\)

Population h: \(\mathbf{y}_{h1}, \mathbf{y}_{h2}, \dots, \mathbf{y}_{hn_h} \sim idd N_p (\mathbf{\mu}_h, \mathbf{\Sigma})\)

Assumptions

- Independent random samples from \(h\) different populations

- Common covariance matrices

- Each population is multivariate normal

Calculate the summary statistics \(\mathbf{\bar{y}}_i, \mathbf{S}\) and the pooled estimate of the covariance matrix \(\mathbf{S}\)

Similar to the univariate one-way ANVOA, we can use the effects model formulation \(\mathbf{\mu}_i = \mathbf{\mu} + \mathbf{\tau}_i\), where

\(\mathbf{\mu}_i\) is the population mean for population i

\(\mathbf{\mu}\) is the overall mean effect

\(\mathbf{\tau}_i\) is the treatment effect of the i-th treatment.

For the one-way model: \(\mathbf{y}_{ij} = \mu + \tau_i + \epsilon_{ij}\) for \(i = 1,..,h; j = 1,..., n_i\) and \(\epsilon_{ij} \sim N_p(\mathbf{0, \Sigma})\)

However, the above model is over-parameterized (i.e., infinite number of ways to define \(\mathbf{\mu}\) and the \(\mathbf{\tau}_i\)’s such that they add up to \(\mu_i\). Thus we can constrain by having

\[ \sum_{i=1}^h n_i \tau_i = 0 \]

or

\[ \mathbf{\tau}_h = 0 \]

The observational equivalent of the effects model is

\[ \begin{aligned} \mathbf{y}_{ij} &= \mathbf{\bar{y}} + (\mathbf{\bar{y}}_i - \mathbf{\bar{y}}) + (\mathbf{y}_{ij} - \mathbf{\bar{y}}_i) \\ &= \text{overall sample mean} + \text{treatement effect} + \text{residual} \text{ (under univariate ANOVA)} \end{aligned} \]

After manipulation

\[ \sum_{i = 1}^h \sum_{j = 1}^{n_i} (\mathbf{\bar{y}}_{ij} - \mathbf{\bar{y}})(\mathbf{\bar{y}}_{ij} - \mathbf{\bar{y}})' = \sum_{i = 1}^h n_i (\mathbf{\bar{y}}_i - \mathbf{\bar{y}})(\mathbf{\bar{y}}_i - \mathbf{\bar{y}})' + \sum_{i=1}^h \sum_{j = 1}^{n_i} (\mathbf{\bar{y}}_{ij} - \mathbf{\bar{y}})(\mathbf{\bar{y}}_{ij} - \mathbf{\bar{y}}_i)' \]

LHS = Total corrected sums of squares and cross products (SSCP) matrix

RHS =

1st term = Treatment (or between subjects) sum of squares and cross product matrix (denoted H;B)

2nd term = residual (or within subject) SSCP matrix denoted (E;W)

Note:

\[ \mathbf{E} = (n_1 - 1)\mathbf{S}_1 + ... + (n_h -1) \mathbf{S}_h = (n-h) \mathbf{S} \]

MANOVA table

| Source | SSCP | df |

|---|---|---|

| Treatment | \(\mathbf{H}\) | \(h -1\) |

| Residual (error) | \(\mathbf{E}\) | \(\sum_{i= 1}^h n_i - h\) |

| Total Corrected | \(\mathbf{H + E}\) | \(\sum_{i=1}^h n_i -1\) |

\[ H_0: \tau_1 = \tau_2 = \dots = \tau_h = \mathbf{0} \]

We consider the relative “sizes” of \(\mathbf{E}\) and \(\mathbf{H+E}\)

Wilk’s Lambda

Define Wilk’s Lambda

\[ \Lambda^* = \frac{|\mathbf{E}|}{|\mathbf{H+E}|} \]

Properties:

Wilk’s Lambda is equivalent to the F-statistic in the univariate case

The exact distribution of \(\Lambda^*\) can be determined for especial cases.

For large sample sizes, reject \(H_0\) if

\[ -(\sum_{i=1}^h n_i - 1 - \frac{p+h}{2}) \log(\Lambda^*) > \chi^2_{(1-\alpha, p(h-1))} \]

22.1.1 Testing General Hypotheses

\(h\) different treatments

with the i-th treatment

applied to \(n_i\) subjects that

are observed for \(p\) repeated measures.

Consider this a \(p\) dimensional obs on a random sample from each of \(h\) different treatment populations.

\[ \mathbf{y}_{ij} = \mathbf{\mu} + \mathbf{\tau}_i + \mathbf{\epsilon}_{ij} \]

for \(i = 1,..,h\) and \(j = 1,..,n_i\)

Equivalently,

\[ \mathbf{Y} = \mathbf{XB} + \mathbf{\epsilon} \]

where \(n = \sum_{i = 1}^h n_i\) and with restriction \(\mathbf{\tau}_h = 0\)

\[ \mathbf{Y}_{(n \times p)} = \left[ \begin{array} {c} \mathbf{y}_{11}' \\ \vdots \\ \mathbf{y}_{1n_1}' \\ \vdots \\ \mathbf{y}_{hn_h}' \end{array} \right], \mathbf{B}_{(h \times p)} = \left[ \begin{array} {c} \mathbf{\mu}' \\ \mathbf{\tau}_1' \\ \vdots \\ \mathbf{\tau}_{h-1}' \end{array} \right], \mathbf{\epsilon}_{(n \times p)} = \left[ \begin{array} {c} \epsilon_{11}' \\ \vdots \\ \epsilon_{1n_1}' \\ \vdots \\ \epsilon_{hn_h}' \end{array} \right] \]

\[ \mathbf{X}_{(n \times h)} = \left[ \begin{array} {ccccc} 1 & 1 & 0 & \ldots & 0 \\ \vdots & \vdots & \vdots & & \vdots \\ 1 & 1 & 0 & \ldots & 0 \\ \vdots & \vdots & \vdots & \ldots & \vdots \\ 1 & 0 & 0 & \ldots & 0 \\ \vdots & \vdots & \vdots & & \vdots \\ 1 & 0 & 0 & \ldots & 0 \end{array} \right] \]

Estimation

\[ \mathbf{\hat{B}} = (\mathbf{X'X})^{-1} \mathbf{X'Y} \]

Rows of \(\mathbf{Y}\) are independent (i.e., \(var(\mathbf{Y}) = \mathbf{I}_n \otimes \mathbf{\Sigma}\) , an \(np \times np\) matrix, where \(\otimes\) is the Kronecker product).

\[ \begin{aligned} &H_0: \mathbf{LBM} = 0 \\ &H_a: \mathbf{LBM} \neq 0 \end{aligned} \]

where

\(\mathbf{L}\) is a \(g \times h\) matrix of full row rank (\(g \le h\)) = comparisons across groups

\(\mathbf{M}\) is a \(p \times u\) matrix of full column rank (\(u \le p\)) = comparisons across traits

The general treatment corrected sums of squares and cross product is

\[ \mathbf{H} = \mathbf{M'Y'X(X'X)^{-1}L'[L(X'X)^{-1}L']^{-1}L(X'X)^{-1}X'YM} \]

or for the null hypothesis \(H_0: \mathbf{LBM} = \mathbf{D}\)

\[ \mathbf{H} = (\mathbf{\hat{LBM}} - \mathbf{D})'[\mathbf{X(X'X)^{-1}L}]^{-1}(\mathbf{\hat{LBM}} - \mathbf{D}) \]

The general matrix of residual sums of squares and cross product

\[ \mathbf{E} = \mathbf{M'Y'[I-X(X'X)^{-1}X']YM} = \mathbf{M'[Y'Y - \hat{B}'(X'X)^{-1}\hat{B}]M} \]

We can compute the following statistic eigenvalues of \(\mathbf{HE}^{-1}\)

Wilk’s Criterion: \(\Lambda^* = \frac{|\mathbf{E}|}{|\mathbf{H} + \mathbf{E}|}\) . The df depend on the rank of \(\mathbf{L}, \mathbf{M}, \mathbf{X}\)

Lawley-Hotelling Trace: \(U = tr(\mathbf{HE}^{-1})\)

Pillai Trace: \(V = tr(\mathbf{H}(\mathbf{H}+ \mathbf{E}^{-1})\)

Roy’s Maximum Root: largest eigenvalue of \(\mathbf{HE}^{-1}\)

If \(H_0\) is true and n is large, \(-(n-1- \frac{p+h}{2})\ln \Lambda^* \sim \chi^2_{p(h-1)}\). Some special values of p and h can give exact F-dist under \(H_0\)

# One-way MANOVA

library(car)

library(emmeans)

library(profileR)

library(tidyverse)

## Read in the data

gpagmat <- read.table("images/gpagmat.dat")

## Change the variable names

names(gpagmat) <- c("y1", "y2", "admit")

## Check the structure

str(gpagmat)

#> 'data.frame': 85 obs. of 3 variables:

#> $ y1 : num 2.96 3.14 3.22 3.29 3.69 3.46 3.03 3.19 3.63 3.59 ...

#> $ y2 : int 596 473 482 527 505 693 626 663 447 588 ...

#> $ admit: int 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 ...

## Plot the data

gg <- ggplot(gpagmat, aes(x = y1, y = y2)) +

geom_text(aes(label = admit, col = as.character(admit))) +

scale_color_discrete(name = "Admission",

labels = c("Admit", "Do not admit", "Borderline")) +

scale_x_continuous(name = "GPA") +

scale_y_continuous(name = "GMAT")

## Fit one-way MANOVA

oneway_fit <- manova(cbind(y1, y2) ~ admit, data = gpagmat)

summary(oneway_fit, test = "Wilks")

#> Df Wilks approx F num Df den Df Pr(>F)

#> admit 1 0.6126 25.927 2 82 1.881e-09 ***

#> Residuals 83

#> ---

#> Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1reject the null of equal multivariate mean vectors between the three admmission groups

# Repeated Measures MANOVA

## Create data frame

stress <- data.frame(

subject = 1:8,

begin = c(3, 2, 5, 6, 1, 5, 1, 5),

middle = c(3, 4, 3, 7, 4, 7, 1, 2),

final = c(6, 7, 4, 7, 6, 7, 3, 5)

)- If independent = time with 3 levels -> univariate ANOVA (require sphericity assumption (i.e., the variances for all differences are equal))

- If each level of independent time as a separate variable -> MANOVA (does not require sphericity assumption)

## MANOVA

stress_mod <- lm(cbind(begin, middle, final) ~ 1, data = stress)

idata <-

data.frame(time = factor(

c("begin", "middle", "final"),

levels = c("begin", "middle", "final")

))

repeat_fit <-

Anova(

stress_mod,

idata = idata,

idesign = ~ time,

icontrasts = "contr.poly"

)

summary(repeat_fit)

#>

#> Type III Repeated Measures MANOVA Tests:

#>

#> ------------------------------------------

#>

#> Term: (Intercept)

#>

#> Response transformation matrix:

#> (Intercept)

#> begin 1

#> middle 1

#> final 1

#>

#> Sum of squares and products for the hypothesis:

#> (Intercept)

#> (Intercept) 1352

#>

#> Multivariate Tests: (Intercept)

#> Df test stat approx F num Df den Df Pr(>F)

#> Pillai 1 0.896552 60.66667 1 7 0.00010808 ***

#> Wilks 1 0.103448 60.66667 1 7 0.00010808 ***

#> Hotelling-Lawley 1 8.666667 60.66667 1 7 0.00010808 ***

#> Roy 1 8.666667 60.66667 1 7 0.00010808 ***

#> ---

#> Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

#>

#> ------------------------------------------

#>

#> Term: time

#>

#> Response transformation matrix:

#> time.L time.Q

#> begin -7.071068e-01 0.4082483

#> middle -7.850462e-17 -0.8164966

#> final 7.071068e-01 0.4082483

#>

#> Sum of squares and products for the hypothesis:

#> time.L time.Q

#> time.L 18.062500 6.747781

#> time.Q 6.747781 2.520833

#>

#> Multivariate Tests: time

#> Df test stat approx F num Df den Df Pr(>F)

#> Pillai 1 0.7080717 7.276498 2 6 0.024879 *

#> Wilks 1 0.2919283 7.276498 2 6 0.024879 *

#> Hotelling-Lawley 1 2.4254992 7.276498 2 6 0.024879 *

#> Roy 1 2.4254992 7.276498 2 6 0.024879 *

#> ---

#> Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

#>

#> Univariate Type III Repeated-Measures ANOVA Assuming Sphericity

#>

#> Sum Sq num Df Error SS den Df F value Pr(>F)

#> (Intercept) 450.67 1 52.00 7 60.6667 0.0001081 ***

#> time 20.58 2 24.75 14 5.8215 0.0144578 *

#> ---

#> Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

#>

#>

#> Mauchly Tests for Sphericity

#>

#> Test statistic p-value

#> time 0.7085 0.35565

#>

#>

#> Greenhouse-Geisser and Huynh-Feldt Corrections

#> for Departure from Sphericity

#>

#> GG eps Pr(>F[GG])

#> time 0.77429 0.02439 *

#> ---

#> Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

#>

#> HF eps Pr(>F[HF])

#> time 0.9528433 0.01611634can’t reject the null hypothesis of sphericity, hence univariate ANOVA is also appropriate.We also see linear significant time effect, but no quadratic time effect

## Polynomial contrasts

# What is the reference for the marginal means?

ref_grid(stress_mod, mult.name = "time")

#> 'emmGrid' object with variables:

#> 1 = 1

#> time = multivariate response levels: begin, middle, final

# marginal means for the levels of time

contr_means <- emmeans(stress_mod, ~ time, mult.name = "time")

contrast(contr_means, method = "poly")

#> contrast estimate SE df t.ratio p.value

#> linear 2.12 0.766 7 2.773 0.0276

#> quadratic 1.38 0.944 7 1.457 0.1885

# MANOVA

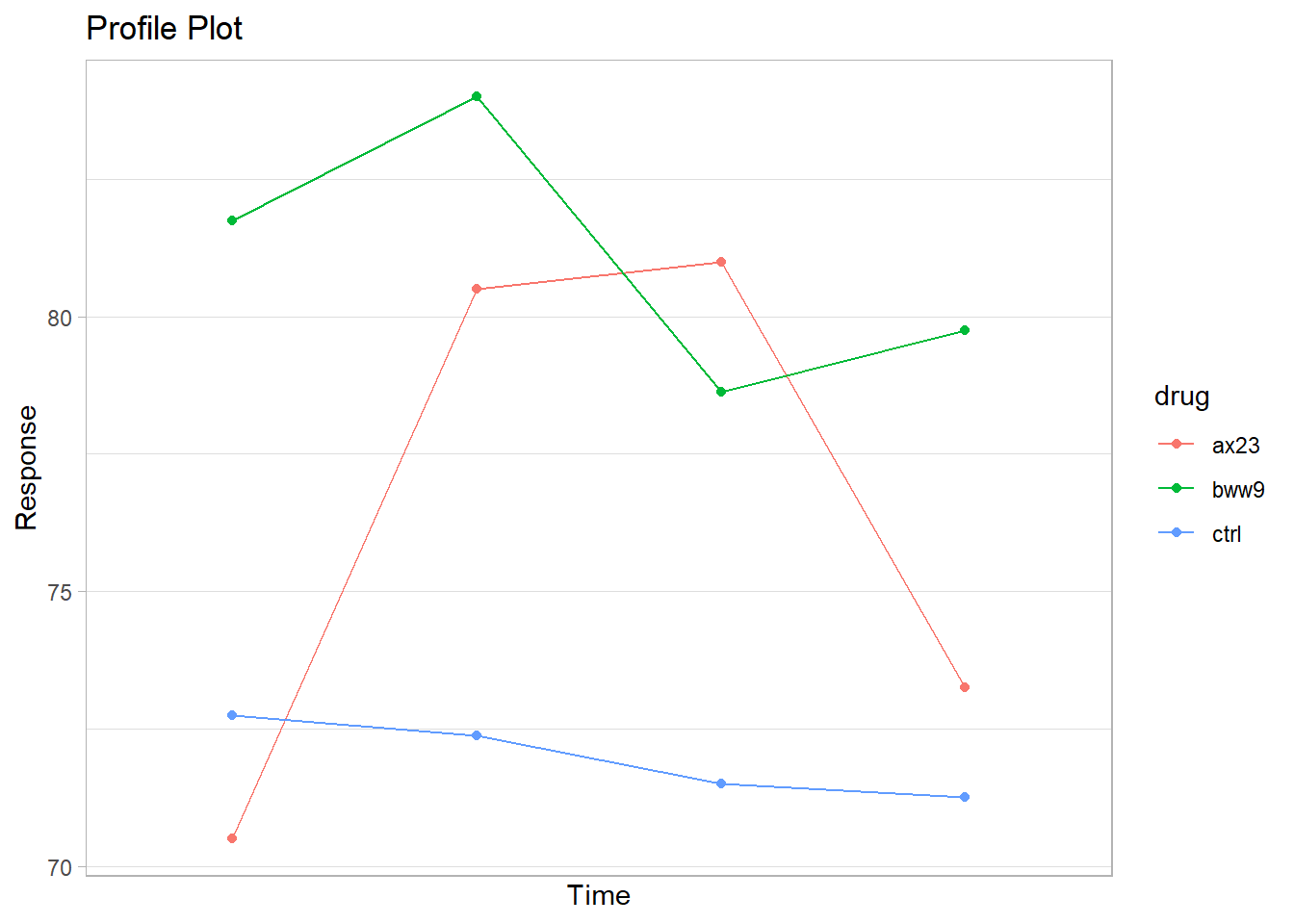

## Read in Data

heart <- read.table("images/heart.dat")

names(heart) <- c("drug", "y1", "y2", "y3", "y4")

## Create a subject ID nested within drug

heart <- heart %>%

group_by(drug) %>%

mutate(subject = row_number()) %>%

ungroup()

str(heart)

#> tibble [24 × 6] (S3: tbl_df/tbl/data.frame)

#> $ drug : chr [1:24] "ax23" "ax23" "ax23" "ax23" ...

#> $ y1 : int [1:24] 72 78 71 72 66 74 62 69 85 82 ...

#> $ y2 : int [1:24] 86 83 82 83 79 83 73 75 86 86 ...

#> $ y3 : int [1:24] 81 88 81 83 77 84 78 76 83 80 ...

#> $ y4 : int [1:24] 77 82 75 69 66 77 70 70 80 84 ...

#> $ subject: int [1:24] 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 1 2 ...

## Create means summary for profile plot,

# pivot longer for plotting with ggplot

heart_means <- heart %>%

group_by(drug) %>%

summarize_at(vars(starts_with("y")), mean) %>%

ungroup() %>%

pivot_longer(-drug, names_to = "time", values_to = "mean") %>%

mutate(time = as.numeric(as.factor(time)))

gg_profile <- ggplot(heart_means, aes(x = time, y = mean)) +

geom_line(aes(col = drug)) +

geom_point(aes(col = drug)) +

ggtitle("Profile Plot") +

scale_y_continuous(name = "Response") +

scale_x_discrete(name = "Time")

gg_profile

## Fit model

heart_mod <- lm(cbind(y1, y2, y3, y4) ~ drug, data = heart)

man_fit <- car::Anova(heart_mod)

summary(man_fit)

#>

#> Type II MANOVA Tests:

#>

#> Sum of squares and products for error:

#> y1 y2 y3 y4

#> y1 641.00 601.750 535.250 426.00

#> y2 601.75 823.875 615.500 534.25

#> y3 535.25 615.500 655.875 555.25

#> y4 426.00 534.250 555.250 674.50

#>

#> ------------------------------------------

#>

#> Term: drug

#>

#> Sum of squares and products for the hypothesis:

#> y1 y2 y3 y4

#> y1 567.00 335.2500 42.7500 387.0

#> y2 335.25 569.0833 404.5417 367.5

#> y3 42.75 404.5417 391.0833 171.0

#> y4 387.00 367.5000 171.0000 316.0

#>

#> Multivariate Tests: drug

#> Df test stat approx F num Df den Df Pr(>F)

#> Pillai 2 1.283456 8.508082 8 38 1.5010e-06 ***

#> Wilks 2 0.079007 11.509581 8 36 6.3081e-08 ***

#> Hotelling-Lawley 2 7.069384 15.022441 8 34 3.9048e-09 ***

#> Roy 2 6.346509 30.145916 4 19 5.4493e-08 ***

#> ---

#> Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1reject the null hypothesis of no difference in means between treatments

## Contrasts

heart$drug <- factor(heart$drug)

L <- matrix(c(0, 2,

1, -1,-1, -1), nrow = 3, byrow = T)

colnames(L) <- c("bww9:ctrl", "ax23:rest")

rownames(L) <- unique(heart$drug)

contrasts(heart$drug) <- L

contrasts(heart$drug)

#> bww9:ctrl ax23:rest

#> ax23 0 2

#> bww9 1 -1

#> ctrl -1 -1

# do not set contrast L if you do further analysis (e.g., Anova, lm)

# do M matrix instead

M <- matrix(c(1, -1, 0, 0,

0, 1, -1, 0,

0, 0, 1, -1), nrow = 4)

## update model to test contrasts

heart_mod2 <- update(heart_mod)

coef(heart_mod2)

#> y1 y2 y3 y4

#> (Intercept) 75.00 78.9583333 77.041667 74.75

#> drugbww9:ctrl 4.50 5.8125000 3.562500 4.25

#> drugax23:rest -2.25 0.7708333 1.979167 -0.75

# Hypothesis test for bww9 vs control after transformation M

# same as linearHypothesis(heart_mod, hypothesis.matrix = c(0,1,-1), P = M)

bww9vctrl <-

car::linearHypothesis(heart_mod2,

hypothesis.matrix = c(0, 1, 0),

P = M)

bww9vctrl

#>

#> Response transformation matrix:

#> [,1] [,2] [,3]

#> y1 1 0 0

#> y2 -1 1 0

#> y3 0 -1 1

#> y4 0 0 -1

#>

#> Sum of squares and products for the hypothesis:

#> [,1] [,2] [,3]

#> [1,] 27.5625 -47.25 14.4375

#> [2,] -47.2500 81.00 -24.7500

#> [3,] 14.4375 -24.75 7.5625

#>

#> Sum of squares and products for error:

#> [,1] [,2] [,3]

#> [1,] 261.375 -141.875 28.000

#> [2,] -141.875 248.750 -19.375

#> [3,] 28.000 -19.375 219.875

#>

#> Multivariate Tests:

#> Df test stat approx F num Df den Df Pr(>F)

#> Pillai 1 0.2564306 2.184141 3 19 0.1233

#> Wilks 1 0.7435694 2.184141 3 19 0.1233

#> Hotelling-Lawley 1 0.3448644 2.184141 3 19 0.1233

#> Roy 1 0.3448644 2.184141 3 19 0.1233

bww9vctrl <-

car::linearHypothesis(heart_mod,

hypothesis.matrix = c(0, 1, -1),

P = M)

bww9vctrl

#>

#> Response transformation matrix:

#> [,1] [,2] [,3]

#> y1 1 0 0

#> y2 -1 1 0

#> y3 0 -1 1

#> y4 0 0 -1

#>

#> Sum of squares and products for the hypothesis:

#> [,1] [,2] [,3]

#> [1,] 27.5625 -47.25 14.4375

#> [2,] -47.2500 81.00 -24.7500

#> [3,] 14.4375 -24.75 7.5625

#>

#> Sum of squares and products for error:

#> [,1] [,2] [,3]

#> [1,] 261.375 -141.875 28.000

#> [2,] -141.875 248.750 -19.375

#> [3,] 28.000 -19.375 219.875

#>

#> Multivariate Tests:

#> Df test stat approx F num Df den Df Pr(>F)

#> Pillai 1 0.2564306 2.184141 3 19 0.1233

#> Wilks 1 0.7435694 2.184141 3 19 0.1233

#> Hotelling-Lawley 1 0.3448644 2.184141 3 19 0.1233

#> Roy 1 0.3448644 2.184141 3 19 0.1233there is no significant difference in means between the control and bww9 drug

# Hypothesis test for ax23 vs rest after transformation M

axx23vrest <-

car::linearHypothesis(heart_mod2,

hypothesis.matrix = c(0, 0, 1),

P = M)

axx23vrest

#>

#> Response transformation matrix:

#> [,1] [,2] [,3]

#> y1 1 0 0

#> y2 -1 1 0

#> y3 0 -1 1

#> y4 0 0 -1

#>

#> Sum of squares and products for the hypothesis:

#> [,1] [,2] [,3]

#> [1,] 438.0208 175.20833 -395.7292

#> [2,] 175.2083 70.08333 -158.2917

#> [3,] -395.7292 -158.29167 357.5208

#>

#> Sum of squares and products for error:

#> [,1] [,2] [,3]

#> [1,] 261.375 -141.875 28.000

#> [2,] -141.875 248.750 -19.375

#> [3,] 28.000 -19.375 219.875

#>

#> Multivariate Tests:

#> Df test stat approx F num Df den Df Pr(>F)

#> Pillai 1 0.855364 37.45483 3 19 3.5484e-08 ***

#> Wilks 1 0.144636 37.45483 3 19 3.5484e-08 ***

#> Hotelling-Lawley 1 5.913921 37.45483 3 19 3.5484e-08 ***

#> Roy 1 5.913921 37.45483 3 19 3.5484e-08 ***

#> ---

#> Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

axx23vrest <-

car::linearHypothesis(heart_mod,

hypothesis.matrix = c(2, -1, 1),

P = M)

axx23vrest

#>

#> Response transformation matrix:

#> [,1] [,2] [,3]

#> y1 1 0 0

#> y2 -1 1 0

#> y3 0 -1 1

#> y4 0 0 -1

#>

#> Sum of squares and products for the hypothesis:

#> [,1] [,2] [,3]

#> [1,] 402.5208 127.41667 -390.9375

#> [2,] 127.4167 40.33333 -123.7500

#> [3,] -390.9375 -123.75000 379.6875

#>

#> Sum of squares and products for error:

#> [,1] [,2] [,3]

#> [1,] 261.375 -141.875 28.000

#> [2,] -141.875 248.750 -19.375

#> [3,] 28.000 -19.375 219.875

#>

#> Multivariate Tests:

#> Df test stat approx F num Df den Df Pr(>F)

#> Pillai 1 0.842450 33.86563 3 19 7.9422e-08 ***

#> Wilks 1 0.157550 33.86563 3 19 7.9422e-08 ***

#> Hotelling-Lawley 1 5.347205 33.86563 3 19 7.9422e-08 ***

#> Roy 1 5.347205 33.86563 3 19 7.9422e-08 ***

#> ---

#> Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1there is a significant difference in means between ax23 drug treatment and the rest of the treatments

22.1.2 Profile Analysis

Examine similarities between the treatment effects (between subjects), which is useful for longitudinal analysis. Null is that all treatments have the same average effect.

\[ H_0: \mu_1 = \mu_2 = \dots = \mu_h \]

Equivalently,

\[ H_0: \tau_1 = \tau_2 = \dots = \tau_h \]

The exact nature of the similarities and differences between the treatments can be examined under this analysis.

Sequential steps in profile analysis:

- Are the profiles parallel? (i.e., is there no interaction between treatment and time)

- Are the profiles coincidental? (i.e., are the profiles identical?)

- Are the profiles horizontal? (i.e., are there no differences between any time points?)

If we reject the null hypothesis that the profiles are parallel, we can test

Are there differences among groups within some subset of the total time points?

Are there differences among time points in a particular group (or groups)?

Are there differences within some subset of the total time points in a particular group (or groups)?

Example

4 times (p = 4)

3 treatments (h=3)

22.1.2.1 Parallel Profile

Are the profiles for each population identical expect for a mean shift?

\[ \begin{aligned} H_0: \mu_{11} - \mu_{21} - \mu_{12} - \mu_{22} = &\dots = \mu_{1t} - \mu_{2t} \\ \mu_{11} - \mu_{31} - \mu_{12} - \mu_{32} = &\dots = \mu_{1t} - \mu_{3t} \\ &\dots \end{aligned} \]

for \(h-1\) equations

Equivalently,

\[ H_0: \mathbf{LBM = 0} \]

\[ \mathbf{LBM} = \left[ \begin{array} {ccc} 1 & -1 & 0 \\ 1 & 0 & -1 \end{array} \right] \left[ \begin{array} {ccc} \mu_{11} & \dots & \mu_{14} \\ \mu_{21} & \dots & \mu_{24} \\ \mu_{31} & \dots & \mu_{34} \end{array} \right] \left[ \begin{array} {ccc} 1 & 1 & 1 \\ -1 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & -1 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & -1 \end{array} \right] = \mathbf{0} \]

where this is the cell means parameterization of \(\mathbf{B}\)

The multiplication of the first 2 matrices \(\mathbf{LB}\) is

\[ \left[ \begin{array} {cccc} \mu_{11} - \mu_{21} & \mu_{12} - \mu_{22} & \mu_{13} - \mu_{23} & \mu_{14} - \mu_{24}\\ \mu_{11} - \mu_{31} & \mu_{12} - \mu_{32} & \mu_{13} - \mu_{33} & \mu_{14} - \mu_{34} \end{array} \right] \]

which is the differences in treatment means at the same time

Multiplying by \(\mathbf{M}\), we get the comparison across time

\[ \left[ \begin{array} {ccc} (\mu_{11} - \mu_{21}) - (\mu_{12} - \mu_{22}) & (\mu_{11} - \mu_{21}) -(\mu_{13} - \mu_{23}) & (\mu_{11} - \mu_{21}) - (\mu_{14} - \mu_{24}) \\ (\mu_{11} - \mu_{31}) - (\mu_{12} - \mu_{32}) & (\mu_{11} - \mu_{31}) - (\mu_{13} - \mu_{33}) & (\mu_{11} - \mu_{31}) -(\mu_{14} - \mu_{34}) \end{array} \right] \]

Alternatively, we can also use the effects parameterization

\[ \mathbf{LBM} = \left[ \begin{array} {cccc} 0 & 1 & -1 & 0 \\ 0 & 1 & 0 & -1 \end{array} \right] \left[ \begin{array} {c} \mu' \\ \tau'_1 \\ \tau_2' \\ \tau_3' \end{array} \right] \left[ \begin{array} {ccc} 1 & 1 & 1 \\ -1 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & -1 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & -1 \end{array} \right] = \mathbf{0} \]

In both parameterizations, \(rank(\mathbf{L}) = h-1\) and \(rank(\mathbf{M}) = p-1\)

We could also choose \(\mathbf{L}\) and \(\mathbf{M}\) in other forms

\[ \mathbf{L} = \left[ \begin{array} {cccc} 0 & 1 & 0 & -1 \\ 0 & 0 & 1 & -1 \end{array} \right] \]

and

\[ \mathbf{M} = \left[ \begin{array} {ccc} 1 & 0 & 0 \\ -1 & 1 & 0 \\ 0 & -1 & 1 \\ 0 & 0 & -1 \end{array} \right] \]

and still obtain the same result.

22.1.2.2 Coincidental Profiles

After we have evidence that the profiles are parallel (i.e., fail to reject the parallel profile test), we can ask whether they are identical?

Given profiles are parallel, then if the sums of the components of \(\mu_i\) are identical for all the treatments, then the profiles are identical.

\[ H_0: \mathbf{1'}_p \mu_1 = \mathbf{1'}_p \mu_2 = \dots = \mathbf{1'}_p \mu_h \]

Equivalently,

\[ H_0: \mathbf{LBM} = \mathbf{0} \]

where for the cell means parameterization

\[ \mathbf{L} = \left[ \begin{array} {ccc} 1 & 0 & -1 \\ 0 & 1 & -1 \end{array} \right] \]

and

\[ \mathbf{M} = \left[ \begin{array} {cccc} 1 & 1 & 1 & 1 \end{array} \right]' \]

multiplication yields

\[ \left[ \begin{array} {c} (\mu_{11} + \mu_{12} + \mu_{13} + \mu_{14}) - (\mu_{31} + \mu_{32} + \mu_{33} + \mu_{34}) \\ (\mu_{21} + \mu_{22} + \mu_{23} + \mu_{24}) - (\mu_{31} + \mu_{32} + \mu_{33} + \mu_{34}) \end{array} \right] = \left[ \begin{array} {c} 0 \\ 0 \end{array} \right] \]

Different choices of \(\mathbf{L}\) and \(\mathbf{M}\) can yield the same result

22.1.2.3 Horizontal Profiles

Given that we can’t reject the null hypothesis that all \(h\) profiles are the same, we can ask whether all of the elements of the common profile equal? (i.e., horizontal)

\[ H_0: \mathbf{LBM} = \mathbf{0} \]

\[ \mathbf{L} = \left[ \begin{array} {ccc} 1 & 0 & 0 \end{array} \right] \]

and

\[ \mathbf{M} = \left[ \begin{array} {ccc} 1 & 0 & 0 \\ -1 & 1 & 0 \\ 0 & -1 & 1 \\ 0 & 0 & -1 \end{array} \right] \]

hence,

\[ \left[ \begin{array} {ccc} (\mu_{11} - \mu_{12}) & (\mu_{12} - \mu_{13}) & (\mu_{13} + \mu_{14}) \end{array} \right] = \left[ \begin{array} {ccc} 0 & 0 & 0 \end{array} \right] \]

Note:

- If we fail to reject all 3 hypotheses, then we fail to reject the null hypotheses of both no difference between treatments and no differences between traits.

| Test | Equivalent test for |

|---|---|

| Parallel profile | Interaction |

| Coincidental profile | main effect of between-subjects factor |

| Horizontal profile | main effect of repeated measures factor |

profile_fit <-

pbg(

data = as.matrix(heart[, 2:5]),

group = as.matrix(heart[, 1]),

original.names = TRUE,

profile.plot = FALSE

)

summary(profile_fit)

#> Call:

#> pbg(data = as.matrix(heart[, 2:5]), group = as.matrix(heart[,

#> 1]), original.names = TRUE, profile.plot = FALSE)

#>

#> Hypothesis Tests:

#> $`Ho: Profiles are parallel`

#> Multivariate.Test Statistic Approx.F num.df den.df p.value

#> 1 Wilks 0.1102861 12.737599 6 38 7.891497e-08

#> 2 Pillai 1.0891707 7.972007 6 40 1.092397e-05

#> 3 Hotelling-Lawley 6.2587852 18.776356 6 36 9.258571e-10

#> 4 Roy 5.9550887 39.700592 3 20 1.302458e-08

#>

#> $`Ho: Profiles have equal levels`

#> Df Sum Sq Mean Sq F value Pr(>F)

#> group 2 328.7 164.35 5.918 0.00915 **

#> Residuals 21 583.2 27.77

#> ---

#> Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

#>

#> $`Ho: Profiles are flat`

#> F df1 df2 p-value

#> 1 14.30928 3 19 4.096803e-05

# reject null hypothesis of parallel profiles

# reject the null hypothesis of coincidental profiles

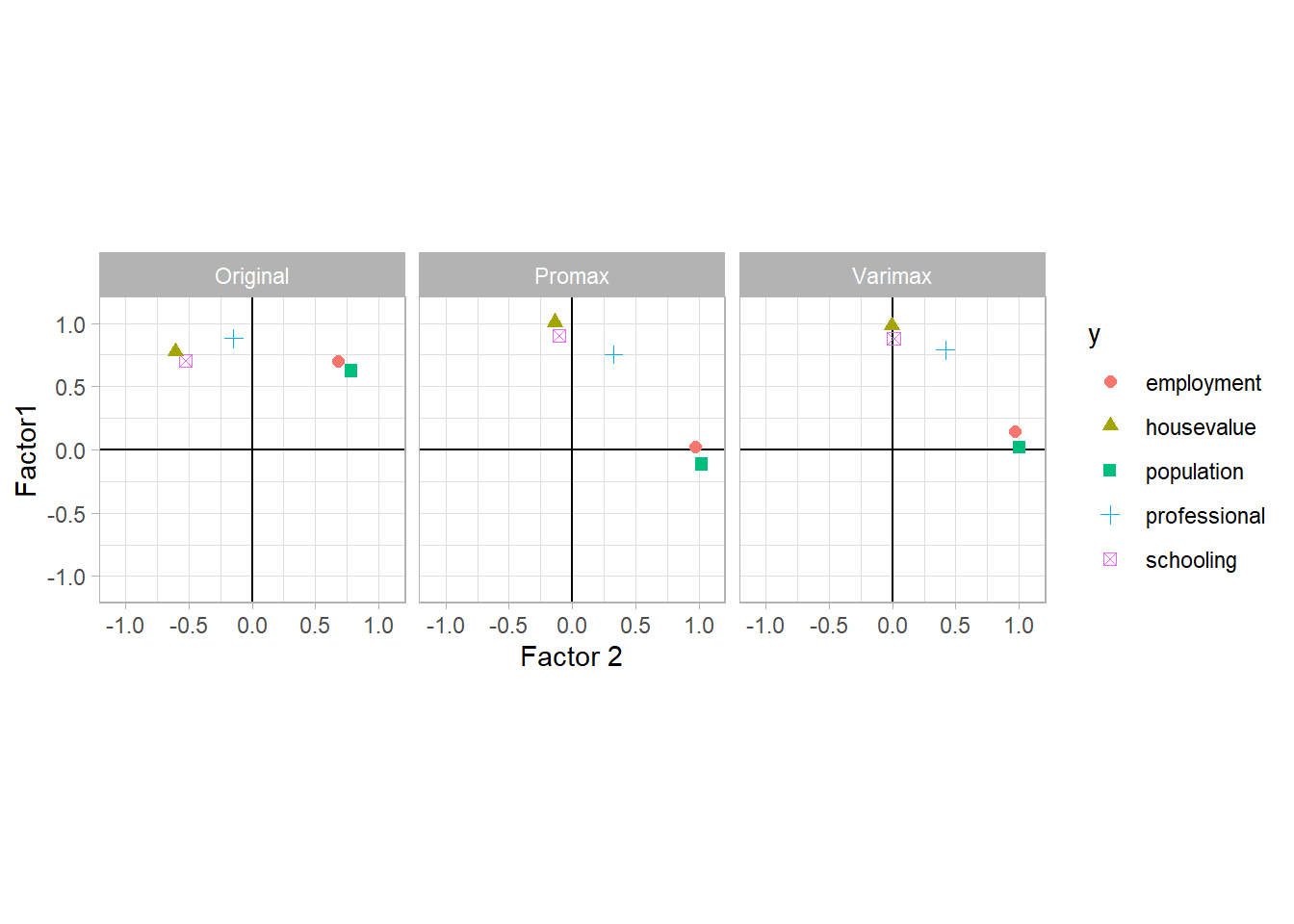

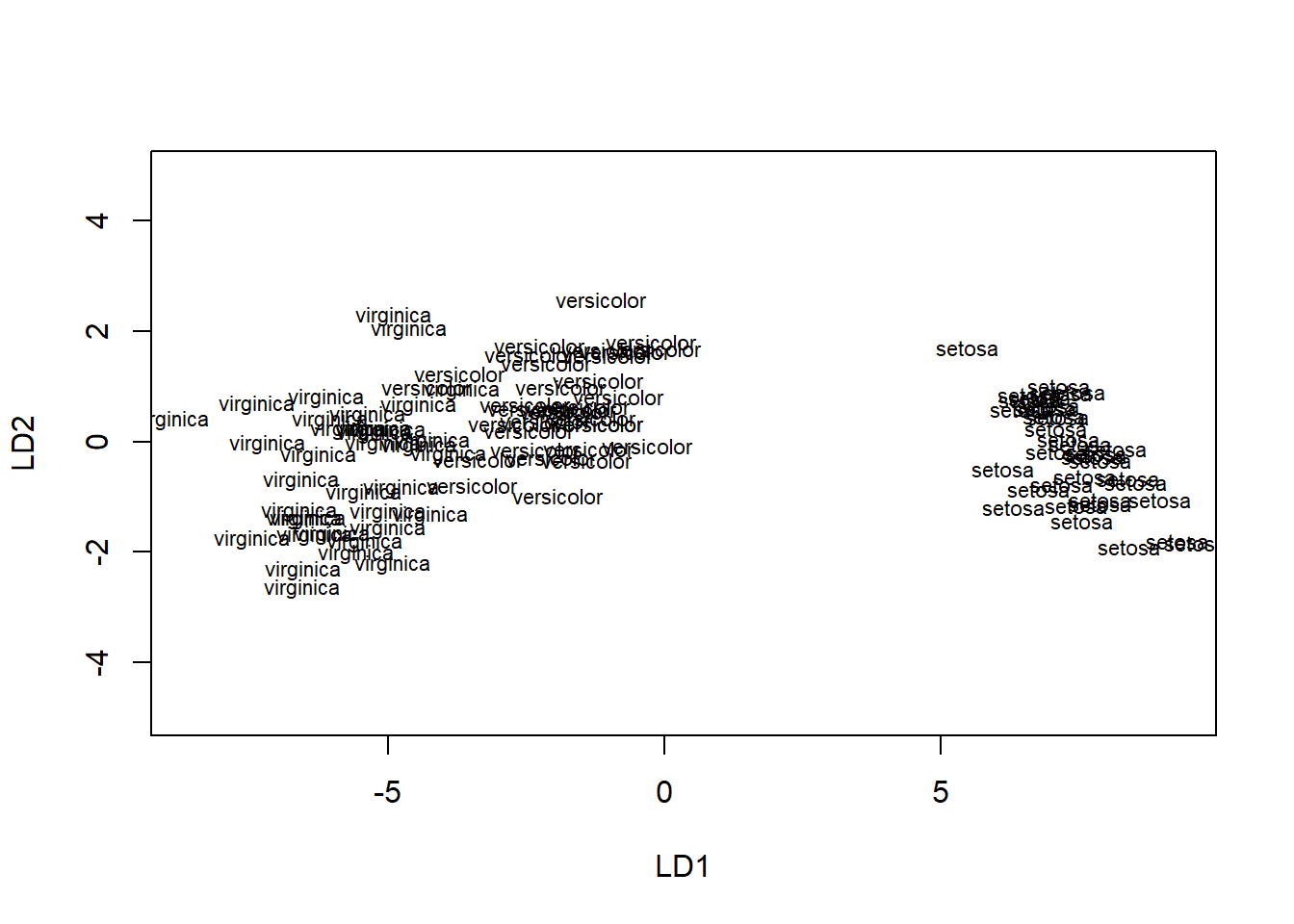

# reject the null hypothesis that the profiles are flat22.2 Principal Components

- Unsupervised learning

- find important features

- reduce the dimensions of the data set

- “decorrelate” multivariate vectors that have dependence.

- uses eigenvector/eigvenvalue decomposition of covariance (correlation) matrices.

According to the “spectral decomposition theorem”, if \(\mathbf{\Sigma}_{p \times p}\) i s a positive semi-definite, symmetric, real matrix, then there exists an orthogonal matrix \(\mathbf{A}\) such that \(\mathbf{A'\Sigma A} = \Lambda\) where \(\Lambda\) is a diagonal matrix containing the eigenvalues \(\mathbf{\Sigma}\)

\[ \mathbf{\Lambda} = \left( \begin{array} {cccc} \lambda_1 & 0 & \ldots & 0 \\ 0 & \lambda_2 & \ldots & 0 \\ \vdots & \vdots & \ddots & \vdots \\ 0 & 0 & \ldots & \lambda_p \end{array} \right) \]

\[ \mathbf{A} = \left( \begin{array} {cccc} \mathbf{a}_1 & \mathbf{a}_2 & \ldots & \mathbf{a}_p \end{array} \right) \]

the i-th column of \(\mathbf{A}\) , \(\mathbf{a}_i\), is the i-th \(p \times 1\) eigenvector of \(\mathbf{\Sigma}\) that corresponds to the eigenvalue, \(\lambda_i\) , where \(\lambda_1 \ge \lambda_2 \ge \ldots \ge \lambda_p\) . Alternatively, express in matrix decomposition:

\[ \mathbf{\Sigma} = \mathbf{A \Lambda A}' \]

\[ \mathbf{\Sigma} = \mathbf{A} \left( \begin{array} {cccc} \lambda_1 & 0 & \ldots & 0 \\ 0 & \lambda_2 & \ldots & 0 \\ \vdots & \vdots& \ddots & \vdots \\ 0 & 0 & \ldots & \lambda_p \end{array} \right) \mathbf{A}' = \sum_{i=1}^p \lambda_i \mathbf{a}_i \mathbf{a}_i' \]

where the outer product \(\mathbf{a}_i \mathbf{a}_i'\) is a \(p \times p\) matrix of rank 1.

For example,

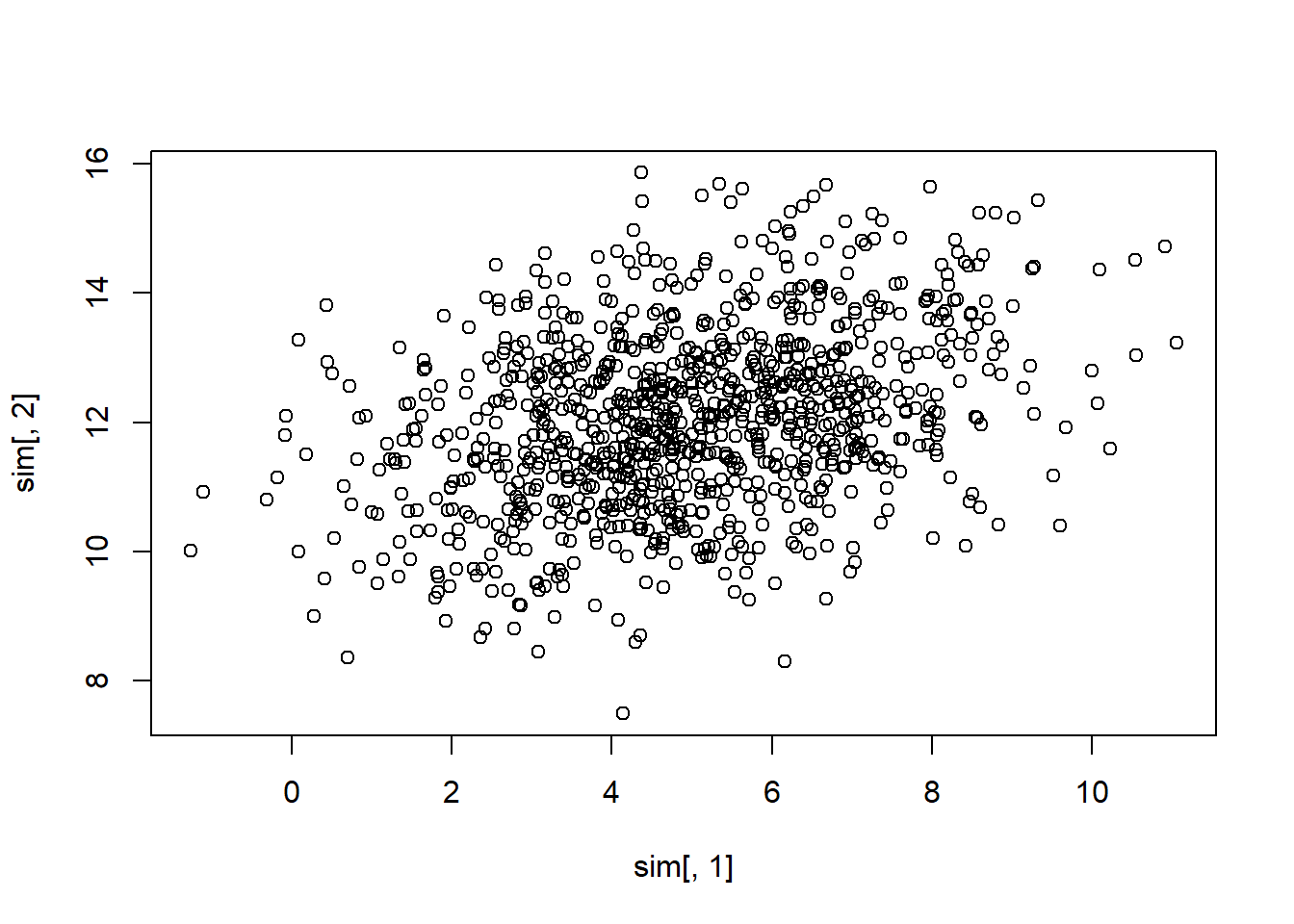

\(\mathbf{x} \sim N_2(\mathbf{\mu}, \mathbf{\Sigma})\)

\[ \mathbf{\mu} = \left( \begin{array} {c} 5 \\ 12 \end{array} \right); \mathbf{\Sigma} = \left( \begin{array} {cc} 4 & 1 \\ 1 & 2 \end{array} \right) \]

library(MASS)

mu = as.matrix(c(5, 12))

Sigma = matrix(c(4, 1, 1, 2), nrow = 2, byrow = T)

sim <- mvrnorm(n = 1000, mu = mu, Sigma = Sigma)

plot(sim[, 1], sim[, 2])

Here,

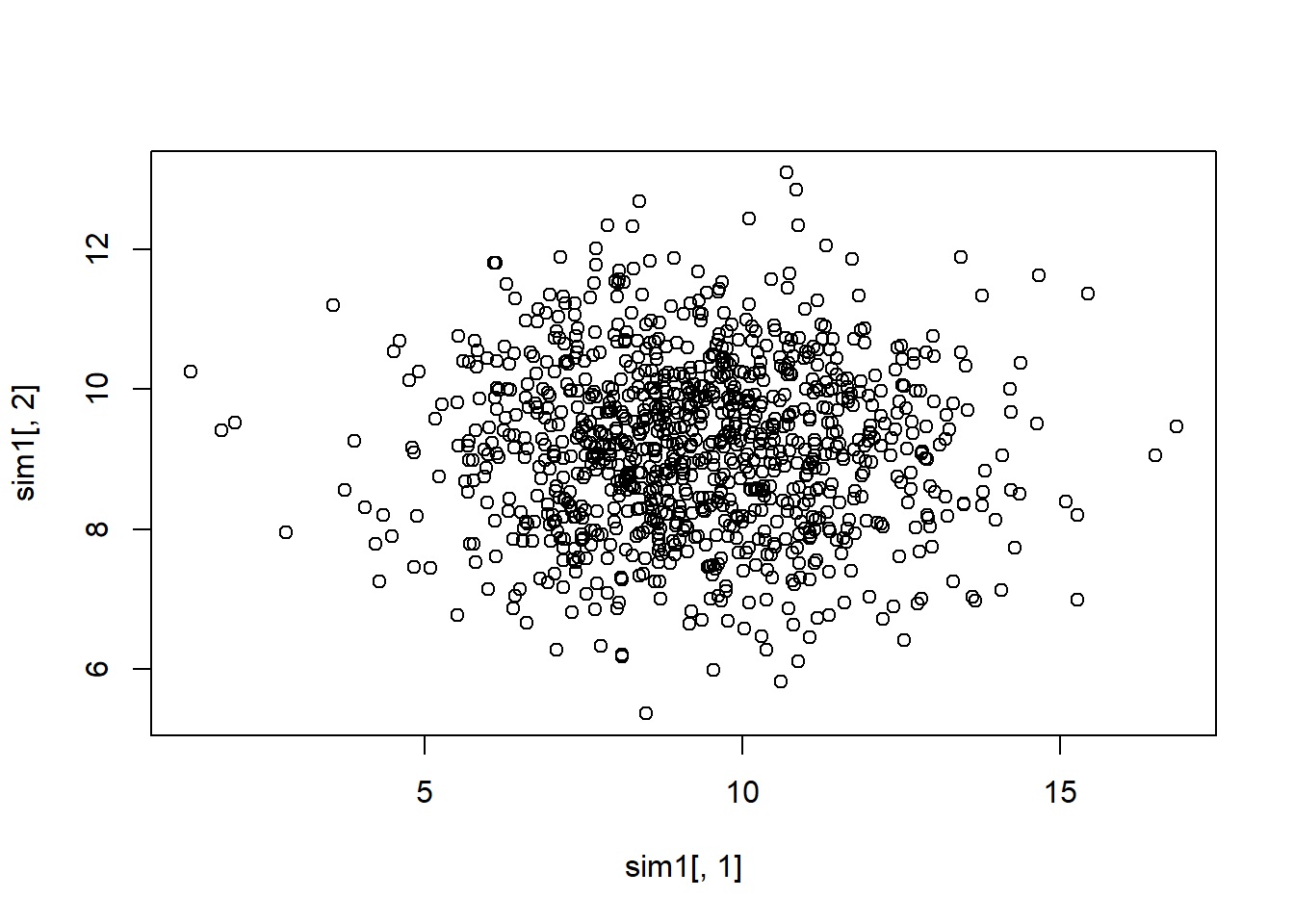

\[ \mathbf{A} = \left( \begin{array} {cc} 0.9239 & -0.3827 \\ 0.3827 & 0.9239 \\ \end{array} \right) \]

Columns of \(\mathbf{A}\) are the eigenvectors for the decomposition

Under matrix multiplication (\(\mathbf{A'\Sigma A}\) or \(\mathbf{A'A}\) ), the off-diagonal elements equal to 0

Multiplying data by this matrix (i.e., projecting the data onto the orthogonal axes); the distribution of the resulting data (i.e., “scores”) is

\[ N_2 (\mathbf{A'\mu,A'\Sigma A}) = N_2 (\mathbf{A'\mu, \Lambda}) \]

Equivalently,

\[ \mathbf{y} = \mathbf{A'x} \sim N \left[ \left( \begin{array} {c} 9.2119 \\ 9.1733 \end{array} \right), \left( \begin{array} {cc} 4.4144 & 0 \\ 0 & 1.5859 \end{array} \right) \right] \]

A_matrix = matrix(c(0.9239, -0.3827, 0.3827, 0.9239),

nrow = 2,

byrow = T)

t(A_matrix) %*% A_matrix

#> [,1] [,2]

#> [1,] 1.000051 0.000000

#> [2,] 0.000000 1.000051

sim1 <-

mvrnorm(

n = 1000,

mu = t(A_matrix) %*% mu,

Sigma = t(A_matrix) %*% Sigma %*% A_matrix

)

plot(sim1[, 1], sim1[, 2])

No more dependence in the data structure, plot

Notes:

The i-th eigenvalue is the variance of a linear combination of the elements of \(\mathbf{x}\) ; \(var(y_i) = var(\mathbf{a'_i x}) = \lambda_i\)

The values on the transformed set of axes (i.e., the \(y_i\)’s) are called the scores. These are the orthogonal projections of the data onto the “new principal component axes

Variances of \(y_1\) are greater than those for any other possible projection

Covariance matrix decomposition and projection onto orthogonal axes = PCA

22.2.1 Population Principal Components

\(p \times 1\) vectors \(\mathbf{x}_1, \dots , \mathbf{x}_n\) which are iid with \(var(\mathbf{x}_i) = \mathbf{\Sigma}\)

The first PC is the linear combination \(y_1 = \mathbf{a}_1' \mathbf{x} = a_{11}x_1 + \dots + a_{1p}x_p\) with \(\mathbf{a}_1' \mathbf{a}_1 = 1\) such that \(var(y_1)\) is the maximum of all linear combinations of \(\mathbf{x}\) which have unit length

The second PC is the linear combination \(y_1 = \mathbf{a}_2' \mathbf{x} = a_{21}x_1 + \dots + a_{2p}x_p\) with \(\mathbf{a}_2' \mathbf{a}_2 = 1\) such that \(var(y_1)\) is the maximum of all linear combinations of \(\mathbf{x}\) which have unit length and uncorrelated with \(y_1\) (i.e., \(cov(\mathbf{a}_1' \mathbf{x}, \mathbf{a}'_2 \mathbf{x}) =0\)

continues for all \(y_i\) to \(y_p\)

\(\mathbf{a}_i\)’s are those that make up the matrix \(\mathbf{A}\) in the symmetric decomposition \(\mathbf{A'\Sigma A} = \mathbf{\Lambda}\) , where \(var(y_1) = \lambda_1, \dots , var(y_p) = \lambda_p\) And the total variance of \(\mathbf{x}\) is

\[ \begin{aligned} var(x_1) + \dots + var(x_p) &= tr(\Sigma) = \lambda_1 + \dots + \lambda_p \\ &= var(y_1) + \dots + var(y_p) \end{aligned} \]

Data Reduction

To reduce the dimension of data from p (original) to k dimensions without much “loss of information”, we can use properties of the population principal components

Suppose \(\mathbf{\Sigma} \approx \sum_{i=1}^k \lambda_i \mathbf{a}_i \mathbf{a}_i'\) . Even thought the true variance-covariance matrix has rank \(p\) , it can be be well approximate by a matrix of rank k (k <p)

New “traits” are linear combinations of the measured traits. We can attempt to make meaningful interpretation fo the combinations (with orthogonality constraints).

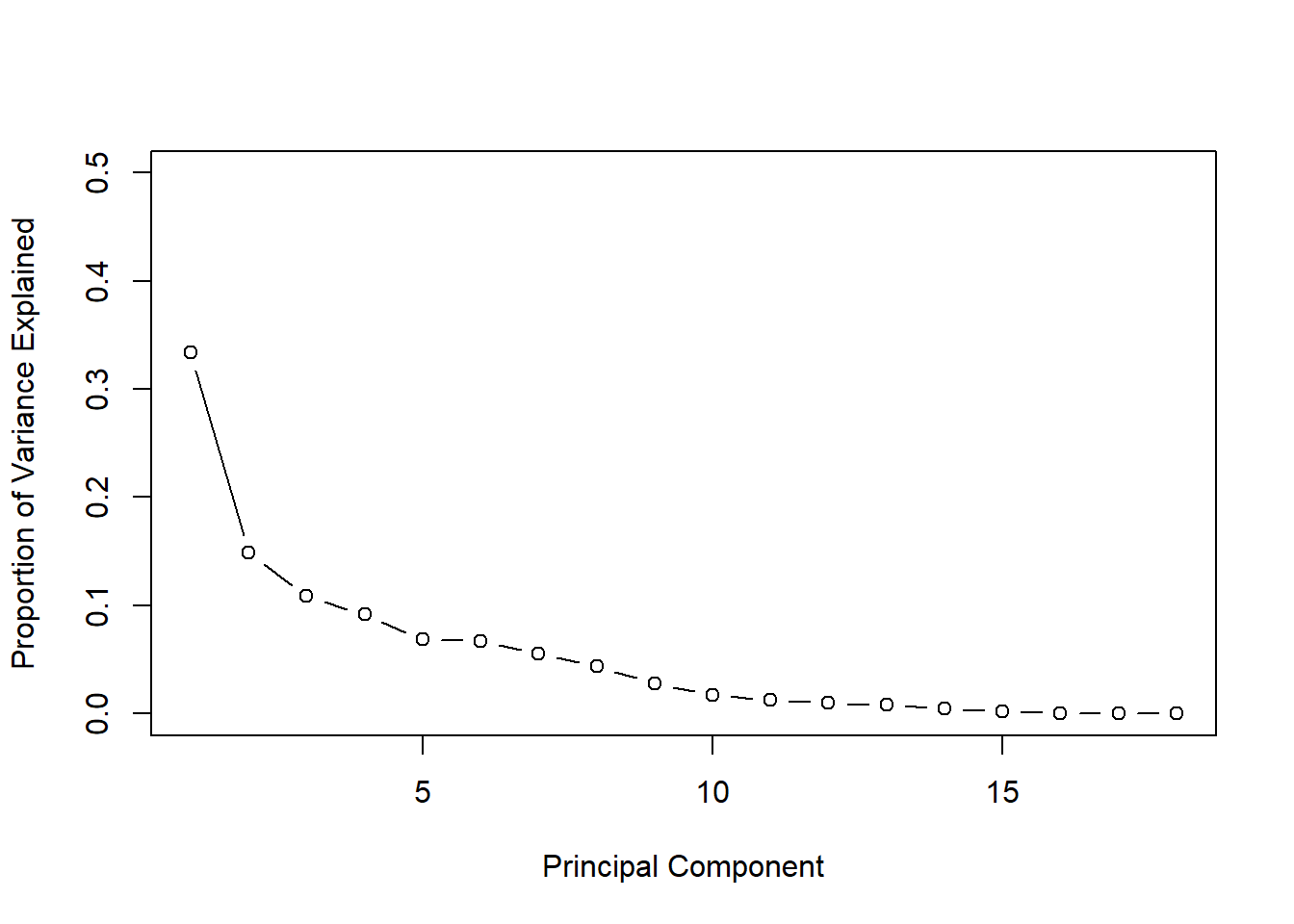

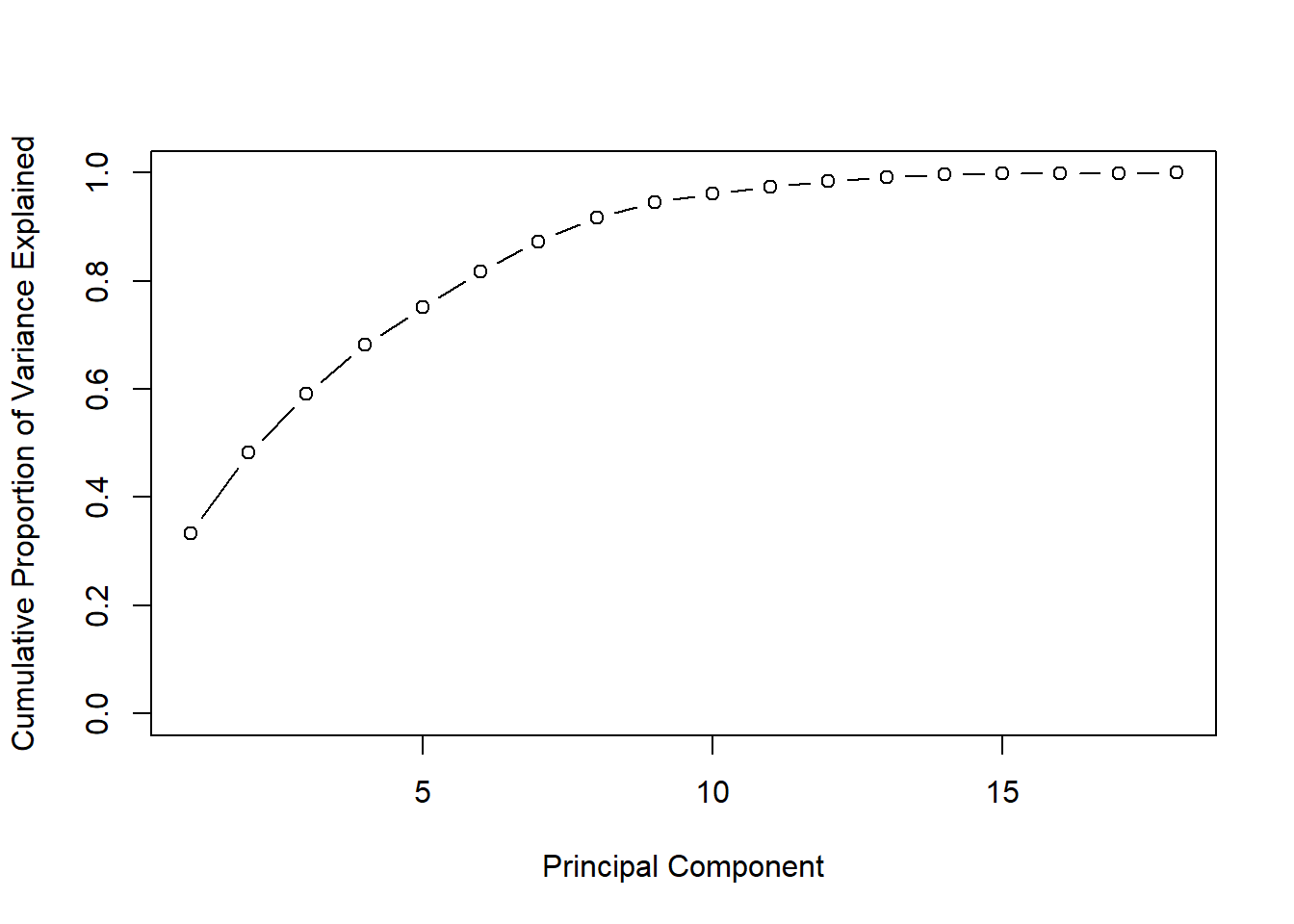

The proportion of the total variance accounted for by the j-th principal component is

\[ \frac{var(y_j)}{\sum_{i=1}^p var(y_i)} = \frac{\lambda_j}{\sum_{i=1}^p \lambda_i} \]

The proportion of the total variation accounted for by the first k principal components is \(\frac{\sum_{i=1}^k \lambda_i}{\sum_{i=1}^p \lambda_i}\)

Above example , we have \(4.4144/(4+2) = .735\) of the total variability can be explained by the first principal component

22.2.2 Sample Principal Components

Since \(\mathbf{\Sigma}\) is unknown, we use

\[ \mathbf{S} = \frac{1}{n-1}\sum_{i=1}^n (\mathbf{x}_i - \bar{\mathbf{x}})(\mathbf{x}_i - \bar{\mathbf{x}})' \]

Let \(\hat{\lambda}_1 \ge \hat{\lambda}_2 \ge \dots \ge \hat{\lambda}_p \ge 0\) be the eigenvalues of \(\mathbf{S}\) and \(\hat{\mathbf{a}}_1, \hat{\mathbf{a}}_2, \dots, \hat{\mathbf{a}}_p\) denote the eigenvectors of \(\mathbf{S}\)

Then, the i-th sample principal component score (or principal component or score) is

\[ \hat{y}_{ij} = \sum_{k=1}^p \hat{a}_{ik}x_{kj} = \hat{\mathbf{a}}_i'\mathbf{x}_j \]

Properties of Sample Principal Components

The estimated variance of \(y_i = \hat{\mathbf{a}}_i'\mathbf{x}_j\) is \(\hat{\lambda}_i\)

The sample covariance between \(\hat{y}_i\) and \(\hat{y}_{i'}\) is 0 when \(i \neq i'\)

The proportion of the total sample variance accounted for by the i-th sample principal component is \(\frac{\hat{\lambda}_i}{\sum_{k=1}^p \hat{\lambda}_k}\)

The estimated correlation between the \(i\)-th principal component score and the \(l\)-th attribute of \(\mathbf{x}\) is

\[ r_{x_l , \hat{y}_i} = \frac{\hat{a}_{il}\sqrt{\lambda_i}}{\sqrt{s_{ll}}} \]

The correlation coefficient is typically used to interpret the components (i.e., if this correlation is high then it suggests that the l-th original trait is important in the i-th principle component). According to R. A. Johnson, Wichern, et al. (2002), pp.433-434, \(r_{x_l, \hat{y}_i}\) only measures the univariate contribution of an individual X to a component Y without taking into account the presence of the other X’s. Hence, some prefer \(\hat{a}_{il}\) coefficient to interpret the principal component.

\(r_{x_l, \hat{y}_i} ; \hat{a}_{il}\) are referred to as “loadings”

To use k principal components, we must calculate the scores for each data vector in the sample

\[ \mathbf{y}_j = \left( \begin{array} {c} y_{1j} \\ y_{2j} \\ \vdots \\ y_{kj} \end{array} \right) = \left( \begin{array} {c} \hat{\mathbf{a}}_1' \mathbf{x}_j \\ \hat{\mathbf{a}}_2' \mathbf{x}_j \\ \vdots \\ \hat{\mathbf{a}}_k' \mathbf{x}_j \end{array} \right) = \left( \begin{array} {c} \hat{\mathbf{a}}_1' \\ \hat{\mathbf{a}}_2' \\ \vdots \\ \hat{\mathbf{a}}_k' \end{array} \right) \mathbf{x}_j \]

Issues:

Large sample theory exists for eigenvalues and eigenvectors of sample covariance matrices if inference is necessary. But we do not do inference with PCA, we only use it as exploratory or descriptive analysis.

-

PC is not invariant to changes in scale (Exception: if all trait are rescaled by multiplying by the same constant, such as feet to inches).

PCA based on the correlation matrix \(\mathbf{R}\) is different than that based on the covariance matrix \(\mathbf{\Sigma}\)

PCA for the correlation matrix is just rescaling each trait to have unit variance

Transform \(\mathbf{x}\) to \(\mathbf{z}\) where \(z_{ij} = (x_{ij} - \bar{x}_i)/\sqrt{s_{ii}}\) where the denominator affects the PCA

After transformation, \(cov(\mathbf{z}) = \mathbf{R}\)

PCA on \(\mathbf{R}\) is calculated in the same way as that on \(\mathbf{S}\) (where \(\hat{\lambda}{}_1 + \dots + \hat{\lambda}{}_p = p\) )

-

The use of \(\mathbf{R}, \mathbf{S}\) depends on the purpose of PCA.

- If the scale of the observations if different, covariance matrix is more preferable. but if they are dramatically different, analysis can still be dominated by the large variance traits.

-

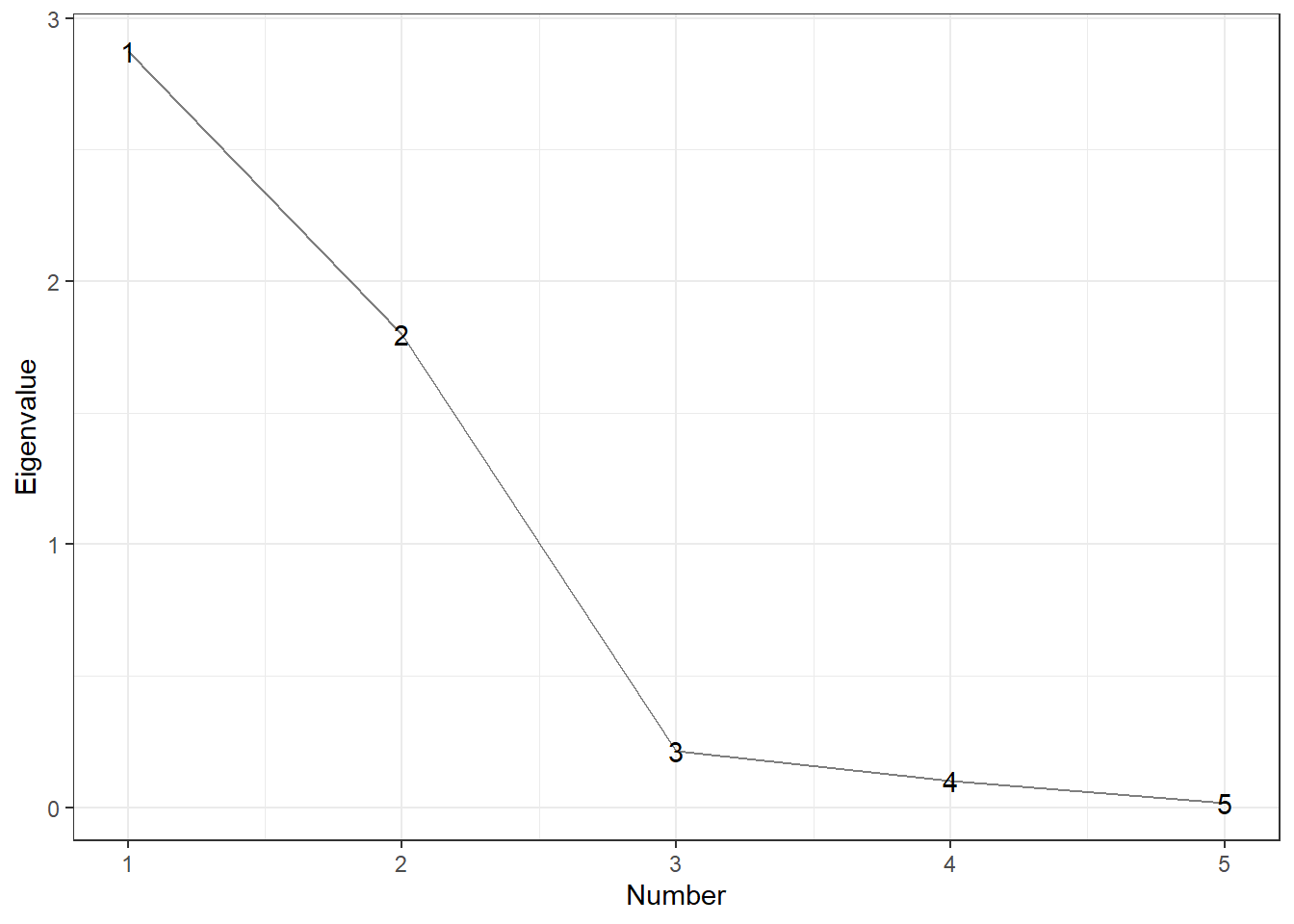

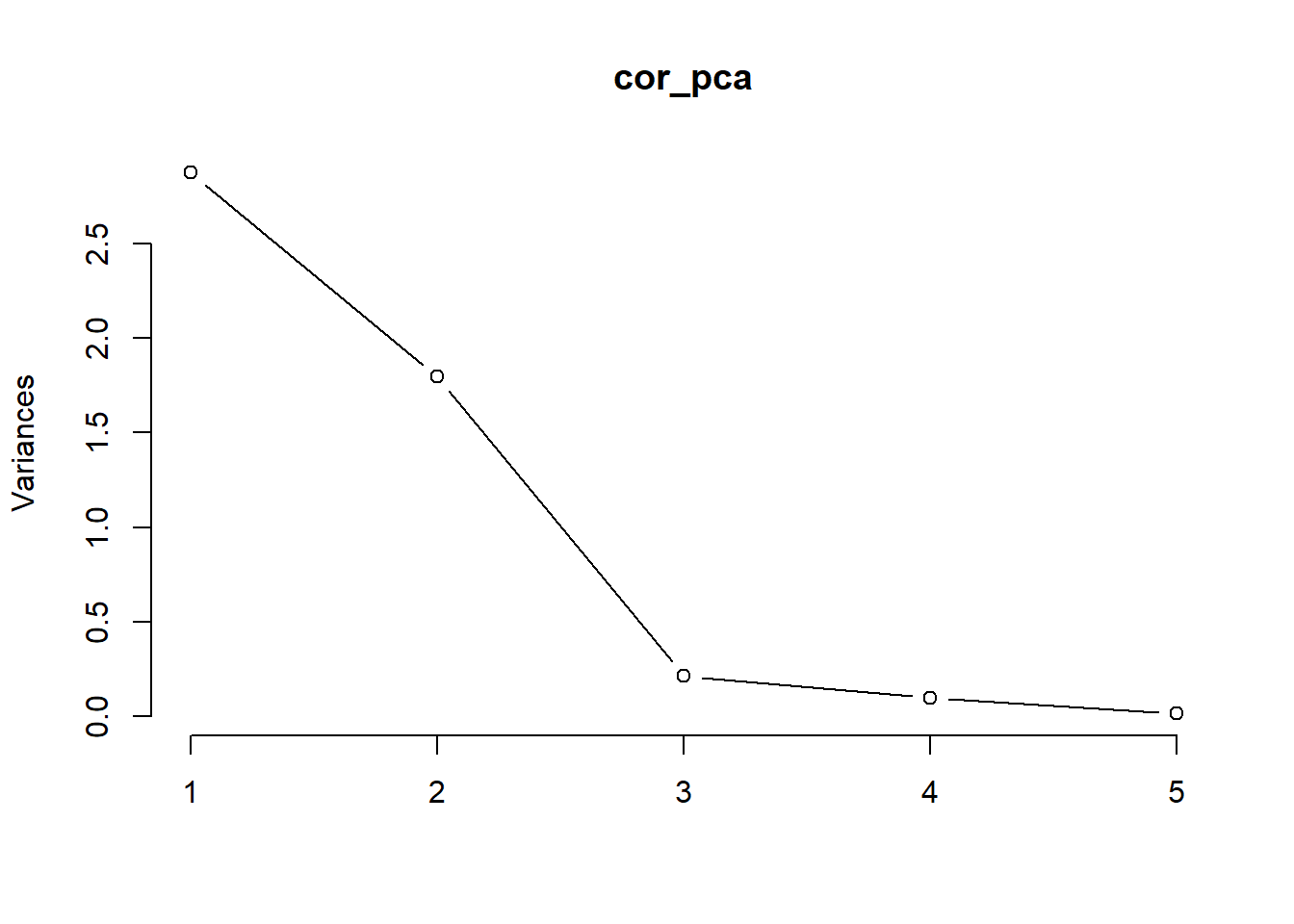

How many PCs to use can be guided by

Scree Graphs: plot the eigenvalues against their indices. Look for the “elbow” where the steep decline in the graph suddenly flattens out; or big gaps.

minimum Percent of total variation (e.g., choose enough components to have 50% or 90%). can be used for interpretations.

Kaiser’s rule: use only those PC with eigenvalues larger than 1 (applied to PCA on the correlation matrix) - ad hoc

Compare to the eigenvalue scree plot of data to the scree plot when the data are randomized.

22.2.3 Application

PCA on the covariance matrix is usually not preferred due to the fact that PCA is not invariant to changes in scale. Hence, PCA on the correlation matrix is more preferred

This also addresses the problem of multicollinearity

The eigvenvectors may differ by a multiplication of -1 for different implementation, but same interpretation.

library(tidyverse)

## Read in and check data

stock <- read.table("images/stock.dat")

names(stock) <- c("allied", "dupont", "carbide", "exxon", "texaco")

str(stock)

#> 'data.frame': 100 obs. of 5 variables:

#> $ allied : num 0 0.027 0.1228 0.057 0.0637 ...

#> $ dupont : num 0 -0.04485 0.06077 0.02995 -0.00379 ...

#> $ carbide: num 0 -0.00303 0.08815 0.06681 -0.03979 ...

#> $ exxon : num 0.0395 -0.0145 0.0862 0.0135 -0.0186 ...

#> $ texaco : num 0 0.0435 0.0781 0.0195 -0.0242 ...

## Covariance matrix of data

cov(stock)

#> allied dupont carbide exxon texaco

#> allied 0.0016299269 0.0008166676 0.0008100713 0.0004422405 0.0005139715

#> dupont 0.0008166676 0.0012293759 0.0008276330 0.0003868550 0.0003109431

#> carbide 0.0008100713 0.0008276330 0.0015560763 0.0004872816 0.0004624767

#> exxon 0.0004422405 0.0003868550 0.0004872816 0.0008023323 0.0004084734

#> texaco 0.0005139715 0.0003109431 0.0004624767 0.0004084734 0.0007587370

## Correlation matrix of data

cor(stock)

#> allied dupont carbide exxon texaco

#> allied 1.0000000 0.5769244 0.5086555 0.3867206 0.4621781

#> dupont 0.5769244 1.0000000 0.5983841 0.3895191 0.3219534

#> carbide 0.5086555 0.5983841 1.0000000 0.4361014 0.4256266

#> exxon 0.3867206 0.3895191 0.4361014 1.0000000 0.5235293

#> texaco 0.4621781 0.3219534 0.4256266 0.5235293 1.0000000

# cov(scale(stock)) # give the same result

## PCA with covariance

cov_pca <- prcomp(stock)

# uses singular value decomposition for calculation and an N -1 divisor

# alternatively, princomp can do PCA via spectral decomposition,

# but it has worse numerical accuracy

# eigen values

cov_results <- data.frame(eigen_values = cov_pca$sdev ^ 2)

cov_results %>%

mutate(proportion = eigen_values / sum(eigen_values),

cumulative = cumsum(proportion))

#> eigen_values proportion cumulative

#> 1 0.0035953867 0.60159252 0.6015925

#> 2 0.0007921798 0.13255027 0.7341428

#> 3 0.0007364426 0.12322412 0.8573669

#> 4 0.0005086686 0.08511218 0.9424791

#> 5 0.0003437707 0.05752091 1.0000000

# first 2 PCs account for 73% variance in the data

# eigen vectors

cov_pca$rotation # prcomp calls rotation

#> PC1 PC2 PC3 PC4 PC5

#> allied 0.5605914 0.73884565 -0.1260222 0.28373183 -0.20846832

#> dupont 0.4698673 -0.09286987 -0.4675066 -0.68793190 0.28069055

#> carbide 0.5473322 -0.65401929 -0.1140581 0.50045312 -0.09603973

#> exxon 0.2908932 -0.11267353 0.6099196 -0.43808002 -0.58203935

#> texaco 0.2842017 0.07103332 0.6168831 0.06227778 0.72784638

# princomp calls loadings.

# first PC = overall average

# second PC compares Allied to Carbide

## PCA with correlation

#same as scale(stock) %>% prcomp

cor_pca <- prcomp(stock, scale = T)

# eigen values

cor_results <- data.frame(eigen_values = cor_pca$sdev ^ 2)

cor_results %>%

mutate(proportion = eigen_values / sum(eigen_values),

cumulative = cumsum(proportion))

#> eigen_values proportion cumulative

#> 1 2.8564869 0.57129738 0.5712974

#> 2 0.8091185 0.16182370 0.7331211

#> 3 0.5400440 0.10800880 0.8411299

#> 4 0.4513468 0.09026936 0.9313992

#> 5 0.3430038 0.06860076 1.0000000

# first egiven values corresponds to less variance

# than PCA based on the covariance matrix

# eigen vectors

cor_pca$rotation

#> PC1 PC2 PC3 PC4 PC5

#> allied 0.4635405 -0.2408499 0.6133570 -0.3813727 0.4532876

#> dupont 0.4570764 -0.5090997 -0.1778996 -0.2113068 -0.6749814

#> carbide 0.4699804 -0.2605774 -0.3370355 0.6640985 0.3957247