4 Basic Statistical Inference

This chapter introduces the core logic of statistical inference, focusing on how we use sample data to make probabilistic statements about populations. We begin with the hypothesis testing framework, including null and alternative hypotheses, test statistics, and \(p\)-values. Key concepts such as confidence intervals and Type I/II errors are explained in depth. Specific methods for one-sample and two-sample inference are discussed, along with inference for categorical data. We also introduce divergence metrics, which provide alternative ways to compare distributions—a concept increasingly important in modern data science applications.

Statistical inference involves drawing conclusions about population parameters based on sample data. The two primary goals of inference are:

-

Making inferences about the true parameter value (\(\beta\)) based on our estimator or estimate:

- This involves interpreting the sample-derived estimate to understand the population parameter.

- Examples include estimating population means, variances, or proportions.

-

Testing whether underlying assumptions hold true, including:

- Assumptions about the true population parameters (e.g., \(\mu\), \(\sigma^2\)).

- Assumptions about random variables (e.g., independence, normality).

- Assumptions about the model specification (e.g., linearity in regression).

Note: Statistical testing does not:

Confirm with absolute certainty that a hypothesis is true or false.

-

Interpret the magnitude of the estimated value in economic, practical, or business contexts without additional analysis.

Statistical significance: Refers to whether an observed effect is unlikely due to chance.

Practical significance: Focuses on the real-world importance of the effect.

Example:

- A marketing campaign increases sales by \(0.5\%\), which is statistically significant (\(p < 0.05\)). However, in a small market, this may lack practical significance.

Instead, inference provides a framework for making probabilistic statements about population parameters, given sample data.

4.1 Hypothesis Testing Framework

Hypothesis testing is one of the fundamental tools in statistics. It provides a formal procedure to test claims or assumptions (hypotheses) about population parameters using sample data. This process is essential in various fields, including business, medicine, and social sciences, as it helps answer questions like “Does a new marketing strategy improve sales?” or “Is there a significant difference in test scores between two teaching methods?”

The goal of hypothesis testing is to make decisions or draw conclusions about a population based on sample data. This is necessary because we rarely have access to the entire population. For example, if a company wants to determine whether a new advertising campaign increases sales, it might analyze data from a sample of stores rather than every store globally.

Key Steps in Hypothesis Testing

- Formulate Hypotheses: Define the null and alternative hypotheses.

- Choose a Significance Level (\(\alpha\)): Determine the acceptable probability of making a Type I error.

- Select a Test Statistic: Identify the appropriate statistical test based on the data and hypotheses.

- Define the Rejection Region: Specify the range of values for which the null hypothesis will be rejected.

- Compute the Test Statistic: Use sample data to calculate the test statistic.

- Make a Decision: Compare the test statistic to the critical value or use the p-value to decide whether to reject or fail to reject the null hypothesis.

4.1.1 Null and Alternative Hypotheses

At the heart of hypothesis testing lies the formulation of two competing hypotheses:

-

Null Hypothesis (\(H_0\)):

- Represents the current state of knowledge, status quo, or no effect.

- It is assumed true unless there is strong evidence against it.

- Examples:

- \(H_0: \mu_1 = \mu_2\) (no difference in means between two groups).

- \(H_0: \beta = 0\) (a predictor variable has no effect in a regression model).

- Think of \(H_0\) as the “default assumption.”

-

Alternative Hypothesis (\(H_a\) or \(H_1\)):

- Represents a claim that contradicts the null hypothesis.

- It is what you are trying to prove or find evidence for.

- Examples:

- \(H_a: \mu_1 \neq \mu_2\) (means of two groups are different).

- \(H_a: \beta \neq 0\) (a predictor variable has an effect).

4.1.2 Errors in Hypothesis Testing

Hypothesis testing involves decision-making under uncertainty, meaning there is always a risk of making errors. These errors are classified into two types:

-

Type I Error (\(\alpha\)):

- Occurs when the null hypothesis is rejected, even though it is true.

- Example: Concluding that a medication is effective when it actually has no effect.

- The probability of making a Type I error is denoted by \(\alpha\), called the significance level (commonly set at 0.05 or 5%).

-

Type II Error (\(\beta\)):

- Occurs when the null hypothesis is not rejected, but the alternative hypothesis is true.

- Example: Failing to detect that a medication is effective when it actually works.

- The complement of \(\beta\) is called the power of the test (\(1 - \beta\)), representing the probability of correctly rejecting the null hypothesis.

Analogy: The Legal System

To make this concept more intuitive, consider the analogy of a courtroom:

- Null Hypothesis (\(H_0\)): The defendant is innocent.

- Alternative Hypothesis (\(H_a\)): The defendant is guilty.

- Type I Error: Convicting an innocent person (false positive).

- Type II Error: Letting a guilty person go free (false negative).

Balancing \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\) is critical in hypothesis testing, as reducing one often increases the other. For example, if you make it harder to reject \(H_0\) (reducing \(\alpha\)), you increase the chance of failing to detect a true effect (increasing \(\beta\)).

4.1.3 The Role of Distributions in Hypothesis Testing

Distributions play a fundamental role in hypothesis testing because they provide a mathematical model for understanding how a test statistic behaves under the null hypothesis (\(H_0\)). Without distributions, it would be impossible to determine whether the observed results are due to random chance or provide evidence to reject the null hypothesis.

4.1.3.1 Expected Outcomes

One of the key reasons distributions are so crucial is that they describe the range of values a test statistic is likely to take when \(H_0\) is true. This helps us understand what is considered “normal” variation in the data due to random chance. For example:

- Imagine you are conducting a study to test whether a new marketing strategy increases the average monthly sales. Under the null hypothesis, you assume the new strategy has no effect, and the average sales remain unchanged.

- When you collect a sample and calculate the test statistic, you compare it to the expected distribution (e.g., the normal distribution for a \(z\)-test). This distribution shows the range of test statistic values that are likely to occur purely due to random fluctuations in the data, assuming \(H_0\) is true.

By providing this baseline of what is “normal,” distributions allow us to identify unusual results that may indicate the null hypothesis is false.

4.1.3.2 Critical Values and Rejection Regions

Distributions also help define critical values and rejection regions in hypothesis testing. Critical values are specific points on the distribution that mark the boundaries of the rejection region. The rejection region is the range of values for the test statistic that lead us to reject \(H_0\).

The location of these critical values depends on:

The level of significance (\(\alpha\)), which is the probability of rejecting \(H_0\) when it is true (a Type I error).

The shape of the test statistic’s distribution under \(H_0\).

For example:

- In a one-tailed \(z\)-test with \(\alpha = 0.05\), the critical value is approximately \(1.645\) for a standard normal distribution. If the calculated test statistic exceeds this value, we reject \(H_0\) because such a result would be very unlikely under \(H_0\).

Distributions help us visually and mathematically determine these critical points. By examining the distribution, we can see where the rejection region lies and what the probability is of observing a value in that region by random chance alone.

4.1.3.3 P-values

The p-value, a central concept in hypothesis testing, is directly derived from the distribution of the test statistic under \(H_0\). The p-value represents the probability of observing a test statistic as extreme as (or more extreme than) the one calculated, assuming \(H_0\) is true.

The p-value quantifies the strength of evidence against \(H_0\). It represents the probability of observing a test statistic as extreme as (or more extreme than) the one calculated, assuming \(H_0\) is true.

- Small p-value (< \(\alpha\)): Strong evidence against \(H_0\); reject \(H_0\).

- Large p-value (> \(\alpha\)): Weak evidence against \(H_0\); fail to reject \(H_0\).

For example:

Suppose you calculate a \(z\)-test statistic of \(2.1\) in a one-tailed test. Using the standard normal distribution, the p-value is the area under the curve to the right of \(z = 2.1\). This area represents the likelihood of observing a result as extreme as \(z = 2.1\) if \(H_0\) is true.

In this case, the p-value is approximately \(0.0179\). A small p-value (typically less than \(\alpha = 0.05\)) suggests that the observed result is unlikely under \(H_0\) and provides evidence to reject the null hypothesis.

4.1.3.4 Why Does All This Matter?

To summarize, distributions are the backbone of hypothesis testing because they allow us to:

Define what is expected under \(H_0\) by modeling the behavior of the test statistic.

Identify results that are unlikely to occur by random chance, which leads to the rejection of \(H_0\).

Calculate p-values to quantify the strength of evidence against \(H_0\).

Distributions provide the framework for understanding the role of chance in statistical analysis. They are essential for determining expected outcomes, setting thresholds for decision-making (critical values and rejection regions), and calculating p-values. A solid grasp of distributions will greatly enhance your ability to interpret and conduct hypothesis tests, making it easier to draw meaningful conclusions from data.

4.1.4 The Test Statistic

The test statistic is a crucial component in hypothesis testing, as it quantifies how far the observed data deviates from what we would expect if the null hypothesis (\(H_0\)) were true. Essentially, it provides a standardized way to compare the observed outcomes against the expectations set by \(H_0\), enabling us to assess whether the observed results are likely due to random chance or indicative of a significant effect.

The general formula for a test statistic is:

\[ \text{Test Statistic} = \frac{\text{Observed Value} - \text{Expected Value under } H_0}{\text{Standard Error}} \]

Each component of this formula has an important role:

-

Numerator:

- The numerator represents the difference between the actual data (observed value) and the hypothetical value (expected value) that is assumed under \(H_0\).

- This difference quantifies the extent of the deviation. A larger deviation suggests stronger evidence against \(H_0\).

-

Denominator:

- The denominator is the standard error, which measures the variability or spread of the data. It accounts for factors such as sample size and the inherent randomness of the data.

- By dividing the numerator by the standard error, the test statistic is standardized, allowing comparisons across different studies, sample sizes, and distributions.

The test statistic plays a central role in determining whether to reject \(H_0\). Once calculated, it is compared to a known distribution (e.g., standard normal distribution for \(z\)-tests or \(t\)-distribution for \(t\)-tests). This comparison allows us to evaluate the likelihood of observing such a test statistic under \(H_0\):

- If the test statistic is close to 0: This indicates that the observed data is very close to what is expected under \(H_0\). There is little evidence to suggest rejecting \(H_0\).

- If the test statistic is far from 0 (in the tails of the distribution): This suggests that the observed data deviates significantly from the expectations under \(H_0\). Such deviations may provide strong evidence against \(H_0\).

4.1.4.1 Why Standardizing Matters

Standardizing the difference between the observed and expected values ensures that the test statistic is not biased by factors such as the scale of measurement or the size of the sample. For instance:

A raw difference of 5 might be highly significant in one context but negligible in another, depending on the variability (standard error).

Standardizing ensures that the magnitude of the test statistic reflects both the size of the difference and the reliability of the sample data.

4.1.4.2 Interpreting the Test Statistic

After calculating the test statistic, it is used to:

- Compare with a critical value: For example, in a \(z\)-test with \(\alpha = 0.05\), the critical values are \(-1.96\) and \(1.96\) for a two-tailed test. If the test statistic falls beyond these values, \(H_0\) is rejected.

- Calculate the p-value: The p-value is derived from the distribution and reflects the probability of observing a test statistic as extreme as the one calculated if \(H_0\) is true.

4.1.5 Critical Values and Rejection Regions

The critical value is a point on the distribution that separates the rejection region from the non-rejection region:

- Rejection Region: If the test statistic falls in this region, we reject \(H_0\).

- Non-Rejection Region: If the test statistic falls here, we fail to reject \(H_0\).

The rejection region depends on the significance level (\(\alpha\)). For a two-tailed test with \(\alpha = 0.05\), the critical values correspond to the top 2.5% and bottom 2.5% of the distribution.

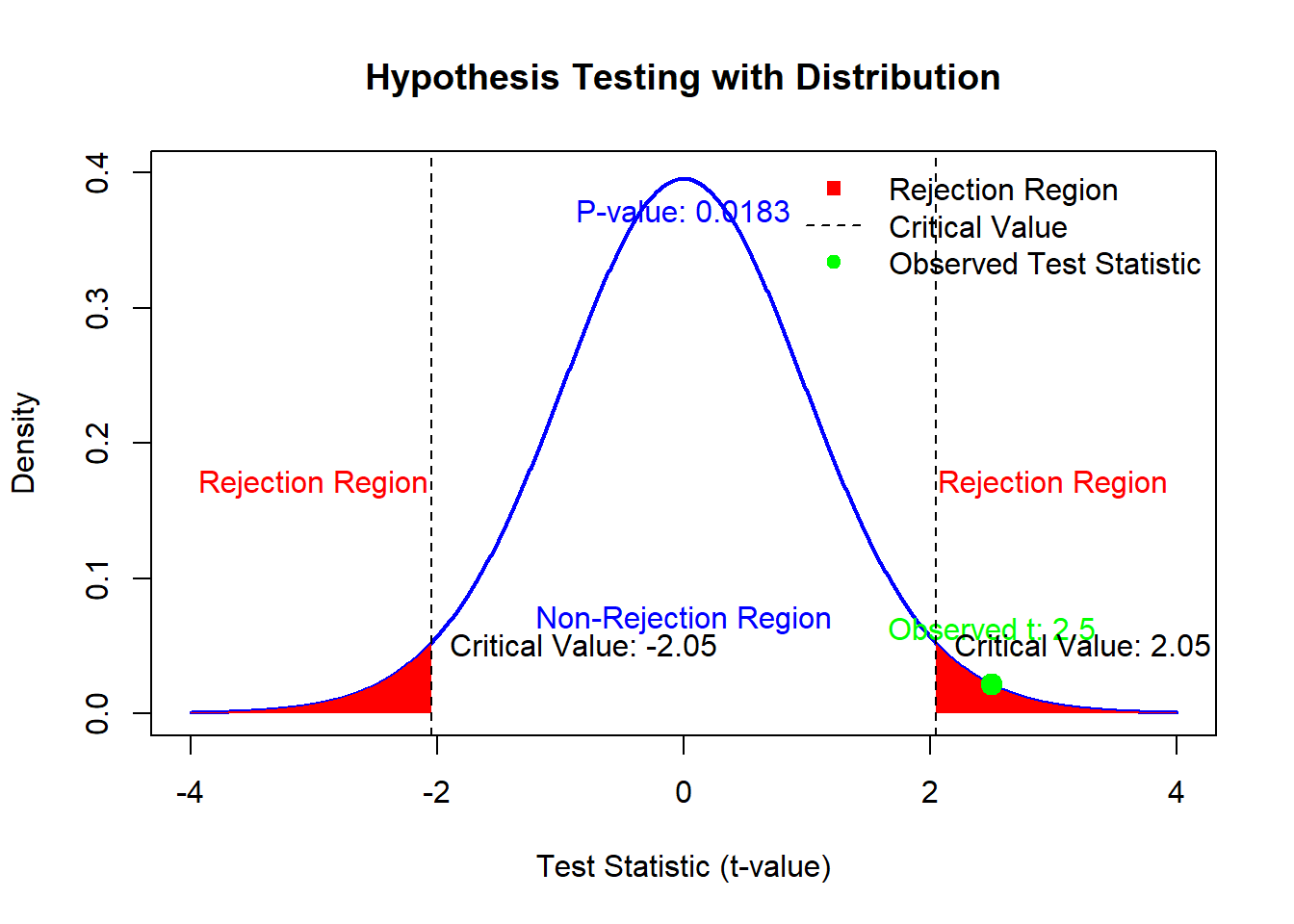

4.1.6 Visualizing Hypothesis Testing

Let’s create a visualization to tie these concepts together:

# Parameters

alpha <- 0.05 # Significance level

df <- 29 # Degrees of freedom (for t-distribution)

t_critical <-

qt(1 - alpha / 2, df) # Critical value for two-tailed test

# Generate t-distribution values

t_values <- seq(-4, 4, length.out = 1000)

density <- dt(t_values, df)

# Observed test statistic

t_obs <- 2.5 # Example observed test statistic

# Plot the t-distribution

plot(

t_values,

density,

type = "l",

lwd = 2,

col = "blue",

main = "Hypothesis Testing with Distribution",

xlab = "Test Statistic (t-value)",

ylab = "Density",

ylim = c(0, 0.4)

)

# Shade the rejection regions

polygon(c(t_values[t_values <= -t_critical], -t_critical),

c(density[t_values <= -t_critical], 0),

col = "red",

border = NA)

polygon(c(t_values[t_values >= t_critical], t_critical),

c(density[t_values >= t_critical], 0),

col = "red",

border = NA)

# Add observed test statistic

points(

t_obs,

dt(t_obs, df),

col = "green",

pch = 19,

cex = 1.5

)

text(

t_obs,

dt(t_obs, df) + 0.02,

paste("Observed t:", round(t_obs, 2)),

col = "green",

pos = 3

)

# Highlight the critical values

abline(

v = c(-t_critical, t_critical),

col = "black",

lty = 2

)

text(

-t_critical,

0.05,

paste("Critical Value:", round(-t_critical, 2)),

pos = 4,

col = "black"

)

text(

t_critical,

0.05,

paste("Critical Value:", round(t_critical, 2)),

pos = 4,

col = "black"

)

# Calculate p-value

p_value <- 2 * (1 - pt(abs(t_obs), df)) # Two-tailed p-value

text(0,

0.35,

paste("P-value:", round(p_value, 4)),

col = "blue",

pos = 3)

# Annotate regions

text(-3,

0.15,

"Rejection Region",

col = "red",

pos = 3)

text(3, 0.15, "Rejection Region", col = "red", pos = 3)

text(0,

0.05,

"Non-Rejection Region",

col = "blue",

pos = 3)

# Add legend

legend(

"topright",

legend = c("Rejection Region", "Critical Value", "Observed Test Statistic"),

col = c("red", "black", "green"),

lty = c(NA, 2, NA),

pch = c(15, NA, 19),

bty = "n"

)

Figure 2.1: Hypothesis Testing with Distribution

4.2 Key Concepts and Definitions

4.2.1 Random Sample

A random sample of size \(n\) consists of \(n\) independent observations, each drawn from the same underlying population distribution. Independence ensures that no observation influences another, and identical distribution guarantees that all observations are governed by the same probability rules.

4.2.2 Sample Statistics

4.2.2.1 Sample Mean

The sample mean is a measure of central tendency:

\[ \bar{X} = \frac{\sum_{i=1}^{n} X_i}{n} \]

- Example: Suppose we measure the heights of 5 individuals (in cm): \(170, 165, 180, 175, 172\). The sample mean is:

\[ \bar{X} = \frac{170 + 165 + 180 + 175 + 172}{5} = 172.4 \text{cm}. \]

4.2.2.2 Sample Median

The sample median is the middle value of ordered data:

\[ \tilde{x} = \begin{cases} \text{Middle observation,} & \text{if } n \text{ is odd}, \\ \text{Average of two middle observations,} & \text{if } n \text{ is even}. \end{cases} \]

4.2.2.3 Sample Variance

The sample variance measures data spread:

\[ S^2 = \frac{\sum_{i=1}^{n}(X_i - \bar{X})^2}{n-1} \]

4.2.2.4 Sample Standard Deviation

The sample standard deviation is the square root of the variance:

\[ S = \sqrt{S^2} \]

4.2.2.5 Sample Proportions

Used for categorical data:

\[ \hat{p} = \frac{X}{n} = \frac{\text{Number of successes}}{\text{Sample size}} \]

4.2.2.6 Estimators

- Point Estimator: A statistic (\(\hat{\theta}\)) used to estimate a population parameter (\(\theta\)).

- Point Estimate:The numerical value assumed by \(\hat{\theta}\) when evaluated for a given sample.

- Unbiased Estimator: A point estimator \(\hat{\theta}\) is unbiased if \(E(\hat{\theta}) = \theta\).

Examples of unbiased estimators:

\(\bar{X}\) for \(\mu\) (population mean).

\(S^2\) for \(\sigma^2\) (population variance).

\(\hat{p}\) for \(p\) (population proportion).

\(\widehat{p_1-p_2}\) for \(p_1- p_2\) (population proportion difference)

\(\bar{X_1} - \bar{X_2}\) for \(\mu_1 - \mu_2\) (population mean difference)

Note: While \(S^2\) is unbiased for \(\sigma^2\), \(S\) is a biased estimator of \(\sigma\).

4.2.3 Distribution of the Sample Mean

The sampling distribution of the mean \(\bar{X}\) depends on:

-

Population Distribution:

- If \(X \sim N(\mu, \sigma^2)\), then \(\bar{X} \sim N\left(\mu, \frac{\sigma^2}{n}\right)\).

-

Central Limit Theorem:

- For large \(n\), \(\bar{X}\) approximately follows a normal distribution, regardless of the population’s shape.

4.2.3.1 Standard Error of the Mean

The standard error quantifies variability in \(\bar{X}\):

\[ \sigma_{\bar{X}} = \frac{\sigma}{\sqrt{n}} \]

Example: Suppose \(\sigma = 10\) and \(n = 25\). Then: \[ \sigma_{\bar{X}} = \frac{10}{\sqrt{25}} = 2. \]

The smaller the standard error, the more precise our estimate of the population mean.

4.3 One-Sample Inference

4.3.1 For Single Mean

Consider a scenario where

\[ Y_i \sim \text{i.i.d. } N(\mu, \sigma^2), \]

where i.i.d. stands for “independent and identically distributed.” This model can be expressed as:

\[ Y_i = \mu + \epsilon_i, \]

where:

- \(\epsilon_i \sim^{\text{i.i.d.}} N(0, \sigma^2)\),

- \(E(Y_i) = \mu\),

- \(\text{Var}(Y_i) = \sigma^2\),

- \(\bar{y} \sim N(\mu, \sigma^2 / n)\).

When \(\sigma^2\) is estimated by \(s^2\), the standardized test statistic follows a \(t\)-distribution:

\[ \frac{\bar{y} - \mu}{s / \sqrt{n}} \sim t_{n-1}. \]

A \(100(1-\alpha)\%\) confidence interval for \(\mu\) is obtained as:

\[ 1 - \alpha = P\left(-t_{\alpha/2;n-1} \leq \frac{\bar{y} - \mu}{s / \sqrt{n}} \leq t_{\alpha/2;n-1}\right), \]

or equivalently,

\[ P\left(\bar{y} - t_{\alpha/2;n-1}\frac{s}{\sqrt{n}} \leq \mu \leq \bar{y} + t_{\alpha/2;n-1}\frac{s}{\sqrt{n}}\right). \]

The confidence interval is expressed as:

\[ \bar{y} \pm t_{\alpha/2;n-1}\frac{s}{\sqrt{n}}, \]

where \(s / \sqrt{n}\) is the standard error of \(\bar{y}\).

If the experiment were repeated many times, \(100(1-\alpha)\%\) of these intervals would contain \(\mu\).

| Case | Confidence Interval \(100(1-\alpha)\%\) | Sample Size (Confidence \(\alpha\), Error \(d\)) | Hypothesis Test Statistic |

|---|---|---|---|

| \(\sigma^2\) known, \(X\) normal (or \(n \geq 25\)) | \(\bar{X} \pm z_{\alpha/2}\frac{\sigma}{\sqrt{n}}\) | \(n \approx \frac{z_{\alpha/2}^2 \sigma^2}{d^2}\) | \(z = \frac{\bar{X} - \mu_0}{\sigma / \sqrt{n}}\) |

| \(\sigma^2\) unknown, \(X\) normal (or \(n \geq 25\)) | \(\bar{X} \pm t_{\alpha/2}\frac{s}{\sqrt{n}}\) | \(n \approx \frac{z_{\alpha/2}^2 s^2}{d^2}\) | \(t = \frac{\bar{X} - \mu_0}{s / \sqrt{n}}\) |

4.3.1.1 Power in Hypothesis Testing

Power (\(\pi(\mu)\)) of a hypothesis test represents the probability of correctly rejecting the null hypothesis (\(H_0\)) when it is false (i.e., when alternative hypothesis \(H_A\) is true). Formally, it is expressed as:

\[ \begin{aligned} \text{Power} &= \pi(\mu) = 1 - \beta \\ &= P(\text{test rejects } H_0|\mu) \\ &= P(\text{test rejects } H_0| H_A \text{ is true}), \end{aligned} \]

where \(\beta\) is the probability of a Type II error (failing to reject \(H_0\) when it is false).

To calculate this probability:

Under \(H_0\): The distribution of the test statistic is centered around the null parameter (e.g., \(\mu_0\)).

Under \(H_A\): The test statistic is distributed differently, shifted according to the true value under \(H_A\) (e.g., \(\mu_1\)).

Hence, to evaluate the power, it is crucial to determine the distribution of the test statistic under the alternative hypothesis, \(H_A\).

Below, we derive the power for both one-sided and two-sided z-tests.

4.3.1.1.1 One-Sided z-Test

Consider the hypotheses:

\[ H_0: \mu \leq \mu_0 \quad \text{vs.} \quad H_A: \mu > \mu_0 \]

The power for a one-sided z-test is derived as follows:

- The test rejects \(H_0\) if \(\bar{y} > \mu_0 + z_{\alpha} \frac{\sigma}{\sqrt{n}}\), where \(z_{\alpha}\) is the critical value for the test at the significance level \(\alpha\).

- Under the alternative hypothesis, the distribution of \(\bar{y}\) is centered at \(\mu\), with standard deviation \(\frac{\sigma}{\sqrt{n}}\).

- The power is then:

\[ \begin{aligned} \pi(\mu) &= P\left(\bar{y} > \mu_0 + z_{\alpha} \frac{\sigma}{\sqrt{n}} \middle| \mu \right) \\ &= P\left(Z > z_{\alpha} + \frac{\mu_0 - \mu}{\sigma / \sqrt{n}} \middle| \mu \right), \quad \text{where } Z = \frac{\bar{y} - \mu}{\sigma / \sqrt{n}} \\ &= 1 - \Phi\left(z_{\alpha} + \frac{(\mu_0 - \mu)\sqrt{n}}{\sigma}\right) \\ &= \Phi\left(-z_{\alpha} + \frac{(\mu - \mu_0)\sqrt{n}}{\sigma}\right). \end{aligned} \]

Here, we use the symmetry of the standard normal distribution: \(1 - \Phi(x) = \Phi(-x)\).

Suppose we wish to show that the mean response \(\mu\) under the treatment is higher than the mean response \(\mu_0\) without treatment (i.e., the treatment effect \(\delta = \mu - \mu_0\) is large).

Since power is an increasing function of \(\mu - \mu_0\), it suffices to find the sample size \(n\) that achieves the desired power \(1 - \beta\) at \(\mu = \mu_0 + \delta\). The power at \(\mu = \mu_0 + \delta\) is:

\[ \pi(\mu_0 + \delta) = \Phi\left(-z_{\alpha} + \frac{\delta \sqrt{n}}{\sigma}\right) = 1 - \beta \]

Given \(\Phi(z_{\beta}) = 1 - \beta\), we have:

\[ -z_{\alpha} + \frac{\delta \sqrt{n}}{\sigma} = z_{\beta} \]

Solving for \(n\), we obtain:

\[ n = \left(\frac{(z_{\alpha} + z_{\beta})\sigma}{\delta}\right)^2 \]

Larger sample sizes are required when:

- The sample variability is large (\(\sigma\) is large).

- The significance level \(\alpha\) is small (\(z_{\alpha}\) is large).

- The desired power \(1 - \beta\) is large (\(z_{\beta}\) is large).

- The magnitude of the effect is small (\(\delta\) is small).

In practice, \(\delta\) and \(\sigma\) are often unknown. To estimate \(\sigma\), you can:

- Use prior studies or pilot studies.

- Approximate \(\sigma\) based on the anticipated range of the observations (excluding outliers). For normally distributed data, dividing the range by 4 provides a reasonable estimate of \(\sigma\).

These considerations ensure the test is adequately powered to detect meaningful effects while balancing practical constraints such as sample size.

4.3.1.1.2 Two-Sided z-Test

For a two-sided test, the hypotheses are:

\[ H_0: \mu = \mu_0 \quad \text{vs.} \quad H_A: \mu \neq \mu_0 \]

The test rejects \(H_0\) if \(\bar{y}\) lies outside the interval \(\mu_0 \pm z_{\alpha/2} \frac{\sigma}{\sqrt{n}}\). The power of the test is:

\[ \begin{aligned} \pi(\mu) &= P\left(\bar{y} < \mu_0 - z_{\alpha/2} \frac{\sigma}{\sqrt{n}} \middle| \mu \right) + P\left(\bar{y} > \mu_0 + z_{\alpha/2} \frac{\sigma}{\sqrt{n}} \middle| \mu \right) \\ &= \Phi\left(-z_{\alpha/2} + \frac{(\mu - \mu_0)\sqrt{n}}{\sigma}\right) + \Phi\left(-z_{\alpha/2} - \frac{(\mu - \mu_0)\sqrt{n}}{\sigma}\right). \end{aligned} \]

To ensure a power of \(1-\beta\) when the treatment effect \(\delta = |\mu - \mu_0|\) is at least a certain value, we solve for \(n\). Since the power function for a two-sided test is increasing and symmetric in \(|\mu - \mu_0|\), it suffices to find \(n\) such that the power equals \(1-\beta\) when \(\mu = \mu_0 + \delta\). This gives:

\[ n = \left(\frac{(z_{\alpha/2} + z_{\beta}) \sigma}{\delta}\right)^2 \]

Alternatively, the required sample size can be determined using a confidence interval approach. For a two-sided \(\alpha\)-level confidence interval of the form:

\[ \bar{y} \pm D \]

where \(D = z_{\alpha/2} \frac{\sigma}{\sqrt{n}}\), solving for \(n\) gives:

\[ n = \left(\frac{z_{\alpha/2} \sigma}{D}\right)^2 \]

This value should be rounded up to the nearest integer to ensure the required precision.

# Generate random data and compute a 95% confidence interval

data <- rnorm(100) # Generate 100 random values

t.test(data, conf.level = 0.95) # Perform t-test with 95% confidence interval

#>

#> One Sample t-test

#>

#> data: data

#> t = -0.0032923, df = 99, p-value = 0.9974

#> alternative hypothesis: true mean is not equal to 0

#> 95 percent confidence interval:

#> -0.2019266 0.2012576

#> sample estimates:

#> mean of x

#> -0.0003344934For a one-sided hypothesis test, such as testing \(H_0: \mu \geq 30\) versus \(H_a: \mu < 30\):

# Perform one-sided t-test

t.test(data, mu = 30, alternative = "less")

#>

#> One Sample t-test

#>

#> data: data

#> t = -295.29, df = 99, p-value < 2.2e-16

#> alternative hypothesis: true mean is less than 30

#> 95 percent confidence interval:

#> -Inf 0.1683576

#> sample estimates:

#> mean of x

#> -0.0003344934When \(\sigma\) is unknown, you can estimate it using:

Prior studies or pilot studies.

The range of observations (excluding outliers) divided by 4, which provides a reasonable approximation for normally distributed data.

4.3.1.1.3 z-Test Summary

- For one-sided tests:

\[ \pi(\mu) = \Phi\left(-z_{\alpha} + \frac{(\mu - \mu_0)\sqrt{n}}{\sigma}\right) \]

- For two-sided tests:

\[ \pi(\mu) = \Phi\left(-z_{\alpha/2} + \frac{(\mu - \mu_0)\sqrt{n}}{\sigma}\right) + \Phi\left(-z_{\alpha/2} - \frac{(\mu - \mu_0)\sqrt{n}}{\sigma}\right) \]

Factors Affecting Power

- Effect Size (\(\mu - \mu_0\)): Larger differences between \(\mu\) and \(\mu_0\) increase power.

- Sample Size (\(n\)): Larger \(n\) reduces the standard error, increasing power.

- Variance (\(\sigma^2\)): Smaller variance increases power.

- Significance Level (\(\alpha\)): Increasing \(\alpha\) (making the test more liberal) increases power through \(z_{\alpha}\).

4.3.1.1.4 One-Sample t-test

In hypothesis testing, calculating the power and determining the required sample size for t-tests are more complex than for z-tests. This complexity arises from the involvement of the Student’s t-distribution and its generalized form, the non-central t-distribution.

The power function for a one-sample t-test can be expressed as:

\[ \pi(\mu) = P\left(\frac{\bar{y} - \mu_0}{s / \sqrt{n}} > t_{n-1; \alpha} \mid \mu \right) \]

Here:

\(\mu_0\) is the hypothesized population mean under the null hypothesis,

\(\bar{y}\) is the sample mean,

\(s\) is the sample standard deviation,

\(n\) is the sample size,

\(t_{n-1; \alpha}\) is the critical t-value from the Student’s t-distribution with \(n-1\) degrees of freedom at significance level \(\alpha\).

When \(\mu > \mu_0\) (i.e., \(\mu - \mu_0 = \delta\)), the random variable

\[ T = \frac{\bar{y} - \mu_0}{s / \sqrt{n}} \]

does not follow the Student’s t-distribution. Instead, it follows a non-central t-distribution with:

a non-centrality parameter \(\lambda = \delta \sqrt{n} / \sigma\), where \(\sigma\) is the population standard deviation,

degrees of freedom \(n-1\).

Key Properties of the Power Function

- The power \(\pi(\mu)\) is an increasing function of the non-centrality parameter \(\lambda\).

- For \(\delta = 0\) (i.e., when the null hypothesis is true), the non-central t-distribution simplifies to the regular Student’s t-distribution.

To calculate the power in practice, numerical procedures (see below) or precomputed charts are typically required.

Approximate Sample Size Adjustment for t-tests

When planning a study, researchers often start with an approximation based on z-tests and then adjust for the specifics of the t-test. Here’s the process:

1. Start with the Sample Size for a z-test

For a two-sided test: \[ n_z = \frac{\left(z_{\alpha/2} + z_\beta\right)^2 \sigma^2}{\delta^2} \] where:

\(z_{\alpha/2}\) is the critical value from the standard normal distribution for a two-tailed test,

\(z_\beta\) corresponds to the desired power \(1 - \beta\),

\(\delta\) is the effect size \(\mu - \mu_0\),

\(\sigma\) is the population standard deviation.

2. Adjust for the t-distribution

Let \(v = n - 1\), where \(n\) is the sample size derived from the z-test. For a two-sided t-test, the approximate sample size is:

\[ n^* = \frac{\left(t_{v; \alpha/2} + t_{v; \beta}\right)^2 \sigma^2}{\delta^2} \]

Here:

\(t_{v; \alpha/2}\) and \(t_{v; \beta}\) are the critical values from the Student’s t-distribution for the significance level \(\alpha\) and desired power, respectively.

Since \(v\) depends on \(n^*\), this process may require iterative refinement.

Notes:

- Approximations: The above formulas provide an intuitive starting point but may require adjustments based on exact numerical solutions.

-

Insights: Power is an increasing function of:

- the effect size \(\delta\),

- the sample size \(n\),

- and a decreasing function of the population variability \(\sigma\).

# Example: Power calculation for a one-sample t-test

library(pwr)

# Parameters

effect_size <- 0.5 # Cohen's d

alpha <- 0.05 # Significance level

power <- 0.8 # Desired power

# Compute sample size

sample_size <-

pwr.t.test(

d = effect_size,

sig.level = alpha,

power = power,

type = "one.sample"

)$n

# Print result

cat("Required sample size for one-sample t-test:",

ceiling(sample_size),

"\n")

#> Required sample size for one-sample t-test: 34

# Power calculation for a given sample size

calculated_power <-

pwr.t.test(

n = ceiling(sample_size),

d = effect_size,

sig.level = alpha,

type = "one.sample"

)$power

cat("Achieved power with computed sample size:",

calculated_power,

"\n")

#> Achieved power with computed sample size: 0.80777754.3.2 For Difference of Means, Independent Samples

| \(100(1-\alpha)%\) Confidence Interval | Hypothesis Testing Test Statistic | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| When \(\sigma^2\) is known | \(\bar{X}_1 - \bar{X}_2 \pm z_{\alpha/2}\sqrt{\frac{\sigma^2_1}{n_1}+\frac{\sigma^2_2}{n_2}}\) | \(z= \frac{(\bar{X}_1-\bar{X}_2)-(\mu_1-\mu_2)_0}{\sqrt{\frac{\sigma^2_1}{n_1}+\frac{\sigma^2_2}{n_2}}}\) | |

| When \(\sigma^2\) is unknown, Variances Assumed EQUAL | \(\bar{X}_1 - \bar{X}_2 \pm t_{\alpha/2}\sqrt{s^2_p(\frac{1}{n_1}+\frac{1}{n_2})}\) | \(t = \frac{(\bar{X}_1-\bar{X}_2)-(\mu_1-\mu_2)_0}{\sqrt{s^2_p(\frac{1}{n_1}+\frac{1}{n_2})}}\) | Pooled Variance: \(s_p^2 = \frac{(n_1 -1)s^2_1 - (n_2-1)s^2_2}{n_1 + n_2 -2}\) Degrees of Freedom: \(\gamma = n_1 + n_2 -2\) |

| When \(\sigma^2\) is unknown, Variances Assumed UNEQUAL | \(\bar{X}_1 - \bar{X}_2 \pm t_{\alpha/2}\sqrt{(\frac{s^2_1}{n_1}+\frac{s^2_2}{n_2})}\) | \(t = \frac{(\bar{X}_1-\bar{X}_2)-(\mu_1-\mu_2)_0}{\sqrt{(\frac{s^2_1}{n_1}+\frac{s^2_2}{n_2})}}\) | Degrees of Freedom: \(\gamma = \frac{(\frac{s_1^2}{n_1}+\frac{s^2_2}{n_2})^2}{\frac{(\frac{s_1^2}{n_1})^2}{n_1-1}+\frac{(\frac{s_2^2}{n_2})^2}{n_2-1}}\) |

4.3.3 For Difference of Means, Paired Samples

| Metric | Formula |

|---|---|

| Confidence Interval | \(\bar{D} \pm t_{\alpha/2}\frac{s_d}{\sqrt{n}}\) |

| Hypothesis Test Statistic | \(t = \frac{\bar{D} - D_0}{s_d / \sqrt{n}}\) |

4.3.4 For Difference of Two Proportions

The mean of the difference between two sample proportions is given by:

\[ \hat{p_1} - \hat{p_2} \]

The variance of the difference in proportions is:

\[ \frac{p_1(1-p_1)}{n_1} + \frac{p_2(1-p_2)}{n_2} \]

A \(100(1-\alpha)\%\) confidence interval for the difference in proportions is calculated as:

\[ \hat{p_1} - \hat{p_2} \pm z_{\alpha/2} \sqrt{\frac{p_1(1-p_1)}{n_1} + \frac{p_2(1-p_2)}{n_2}} \]

where

\(z_{\alpha/2}\): The critical value from the standard normal distribution.

\(\hat{p_1}\), \(\hat{p_2}\): Sample proportions.

\(n_1\), \(n_2\): Sample sizes.

Sample Size for a Desired Confidence Level and Margin of Error

To achieve a margin of error \(d\) for a given confidence level, the required sample size can be estimated as follows:

With Prior Estimates of \(\hat{p_1}\) and \(\hat{p_2}\): \[ n \approx \frac{z_{\alpha/2}^2 \left[p_1(1-p_1) + p_2(1-p_2)\right]}{d^2} \]

Without Prior Estimates (assuming maximum variability, \(\hat{p} = 0.5\)): \[ n \approx \frac{z_{\alpha/2}^2}{2d^2} \]

Hypothesis Testing for Difference in Proportions

The test statistic for hypothesis testing depends on the null hypothesis:

When \((p_1 - p_2) \neq 0\): \[ z = \frac{(\hat{p_1} - \hat{p_2}) - (p_1 - p_2)_0}{\sqrt{\frac{p_1(1-p_1)}{n_1} + \frac{p_2(1-p_2)}{n_2}}} \]

When \((p_1 - p_2)_0 = 0\) (testing equality of proportions): \[ z = \frac{\hat{p_1} - \hat{p_2}}{\sqrt{\hat{p}(1-\hat{p}) \left(\frac{1}{n_1} + \frac{1}{n_2}\right)}} \]

where \(\hat{p}\) is the pooled sample proportion:

\[ \hat{p} = \frac{x_1 + x_2}{n_1 + n_2} = \frac{n_1\hat{p_1} + n_2\hat{p_2}}{n_1 + n_2} \]

4.3.5 For Single Proportion

The \(100(1-\alpha)\%\) confidence interval for a population proportion \(p\) is:

\[ \hat{p} \pm z_{\alpha/2} \sqrt{\frac{\hat{p}(1-\hat{p})}{n}} \]

Sample Size Determination

With Prior Estimate (\(\hat{p}\)): \[ n \approx \frac{z_{\alpha/2}^2 \hat{p}(1-\hat{p})}{d^2} \]

Without Prior Estimate: \[ n \approx \frac{z_{\alpha/2}^2}{4d^2} \]

The test statistic for \(H_0: p = p_0\) is:

\[ z = \frac{\hat{p} - p_0}{\sqrt{\frac{p_0(1-p_0)}{n}}} \]

4.3.6 For Single Variance

For a sample variance \(s^2\) with \(n\) observations, the \(100(1-\alpha)\%\) confidence interval for the population variance \(\sigma^2\) is:

\[ \begin{aligned} 1 - \alpha &= P( \chi_{1-\alpha/2;n-1}^2) \le (n-1)s^2/\sigma^2 \le \chi_{\alpha/2;n-1}^2)\\ &=P\left(\frac{(n-1)s^2}{\chi^2_{\alpha/2; n-1}} \leq \sigma^2 \leq \frac{(n-1)s^2}{\chi^2_{1-\alpha/2; n-1}}\right) \end{aligned} \]

Equivalently, the confidence interval can be written as:

\[ \left(\frac{(n-1)s^2}{\chi^2_{\alpha/2}}, \frac{(n-1)s^2}{\chi^2_{1-\alpha/2}}\right) \]

To find confidence limits for \(\sigma\), compute the square root of the interval bounds:

\[ \text{Confidence Interval for } \sigma: \quad \left(\sqrt{\frac{(n-1)s^2}{\chi^2_{\alpha/2}}}, \sqrt{\frac{(n-1)s^2}{\chi^2_{1-\alpha/2}}}\right) \]

Hypothesis Testing for Variance

The test statistic for testing a null hypothesis about a population variance (\(\sigma^2_0\)) is:

\[ \chi^2 = \frac{(n-1)s^2}{\sigma^2_0} \]

This test statistic follows a chi-squared distribution with \(n-1\) degrees of freedom under the null hypothesis.

4.3.7 Non-parametric Tests

| Method | Purpose | Assumptions |

|---|---|---|

| Sign Test | Test median | None (ordinal data sufficient) |

| Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test | Test symmetry around a value | Symmetry of distribution |

| Wald-Wolfowitz Runs Test | Test for randomness | Independent observations |

| Quantile (or Percentile) Test | Test specific quantile | None (ordinal data sufficient) |

4.3.7.1 Sign Test

The Sign Test is used to test hypotheses about the median of a population, \(\mu_{(0.5)}\), without assuming a specific distribution for the data. This test is ideal for small sample sizes or when normality assumptions are not met.

To test the population median, consider the hypotheses:

- Null Hypothesis: \(H_0: \mu_{(0.5)} = 0\)

- Alternative Hypothesis: \(H_a: \mu_{(0.5)} > 0\) (one-sided test)

Steps:

-

Count Positive and Negative Deviations:

- Count observations (\(y_i\)) greater than 0: \(s_+\) (number of positive signs).

- Count observations less than 0: \(s_-\) (number of negative signs).

- \(s_- = n - s_+\).

-

Decision Rule:

- Reject \(H_0\) if \(s_+\) is large (or equivalently, \(s_-\) is small).

- To determine how large \(s_+\) must be, use the distribution of \(S_+\) under \(H_0\), which is Binomial with \(p = 0.5\).

Null Distribution:

Under \(H_0\), \(S_+\) follows: \[ S_+ \sim Binomial(n, p = 0.5) \]Critical Value:

Reject \(H_0\) if: \[ s_+ \ge b_{n,\alpha} \] where \(b_{n,\alpha}\) is the upper \(\alpha\) critical value of the binomial distribution.-

p-value Calculation:

Compute the p-value for the observed (one-tailed) \(s_+\) as: \[ \text{p-value} = P(S \ge s_+) = \sum_{i=s_+}^{n} \binom{n}{i} \left(\frac{1}{2}\right)^n \]Alternatively: \[ P(S \le s_-) = \sum_{i=0}^{s_-} \binom{n}{i} \left(\frac{1}{2}\right)^n \]

Large Sample Normal Approximation

For large \(n\), use a normal approximation for the binomial test. Reject \(H_0\) if: \[ s_+ \ge \frac{n}{2} + \frac{1}{2} + z_{\alpha} \sqrt{\frac{n}{4}} \] where \(z_\alpha\) is the critical value for a one-sided test.

For two-sided tests, use the maximum or minimum of \(s_+\) and \(s_-\):

Test statistic: \(s_{\text{max}} = \max(s_+, s_-)\) or \(s_{\text{min}} = \min(s_+, s_-)\)

Reject \(H_0\) if \(p\)-value is less than \(\alpha\), where: \[ p\text{-value} = 2 \sum_{i=s_{\text{max}}}^{n} \binom{n}{i} \left(\frac{1}{2}\right)^n = 2 \sum_{i = 0}^{s_{min}} \binom{n}{i} \left( \frac{1}{2} \right)^n \]

Equivalently, rejecting \(H_0\) if \(s_{max} \ge b_{n,\alpha/2}\).

For large \(n\), the normal approximation uses: \[

z = \frac{s_{\text{max}} - \frac{n}{2} - \frac{1}{2}}{\sqrt{\frac{n}{4}}}

\]

Reject \(H_0\) at \(\alpha\) if \(z \ge z_{\alpha/2}\).

Handling zeros in the data is a common issue with the Sign Test:

- Random Assignment: Assign zeros randomly to either \(s_+\) or \(s_-\) (2 researchers might get different results).

- Fractional Assignment: Count each zero as \(0.5\) toward both \(s_+\) and \(s_-\) (but then we could not apply the Binomial Distribution afterward).

- Ignore Zeros: Ignore zeros, but note this reduces the sample size and power.

# Example Data

data <- c(0.76, 0.82, 0.80, 0.79, 1.06, 0.83, -0.43, -0.34, 3.34, 2.33)

# Count positive signs

s_plus <- sum(data > 0)

# Sample size excluding zeros

n <- length(data)

# Perform a one-sided binomial test

binom.test(s_plus, n, p = 0.5, alternative = "greater")

#>

#> Exact binomial test

#>

#> data: s_plus and n

#> number of successes = 8, number of trials = 10, p-value = 0.05469

#> alternative hypothesis: true probability of success is greater than 0.5

#> 95 percent confidence interval:

#> 0.4930987 1.0000000

#> sample estimates:

#> probability of success

#> 0.84.3.7.2 Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test

The Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test is an improvement over the Sign Test as it considers both the magnitude and direction of deviations from the null hypothesis value (e.g., 0). However, this test assumes that the data are symmetrically distributed around the median, unlike the Sign Test.

We test the following hypotheses:

\[ \begin{aligned} H_0: \mu_{(0.5)} &= 0\\ H_a: \mu_{(0.5)} &> 0 \end{aligned} \]

This example assumes no ties or duplicate observations in the data.

Procedure for the Signed Rank Test

-

Rank the Absolute Values:

- Rank the observations \(y_i\) based on their absolute values.

- Let \(r_i\) denote the rank of \(y_i\).

- Since there are no ties, ranks \(r_i\) are uniquely determined and form a permutation of integers \(1, 2, \dots, n\).

-

Calculate \(w_+\) and \(w_-\):

- \(w_+\) is the sum of the ranks corresponding to positive values of \(y_i\).

- \(w_-\) is the sum of the ranks corresponding to negative values of \(y_i\).

- By definition: \[ w_+ + w_- = \sum_{i=1}^n r_i = \frac{n(n+1)}{2} \]

-

Decision Rule:

- Reject \(H_0\) if \(w_+\) is large (or equivalently, if \(w_-\) is small).

Null Distribution of \(W_+\)

Under the null hypothesis, the distributions of \(W_+\) and \(W_-\) are identical and symmetric. The p-value for a one-sided test is:

\[ \text{p-value} = P(W \ge w_+) = P(W \le w_-) \]

An \(\alpha\)-level test rejects \(H_0\) if \(w_+ \ge w_{n,\alpha}\), where \(w_{n,\alpha}\) is the critical value from a table of the null distribution of \(W_+\).

For two-sided tests, use:

\[ p\text{-value} = 2P(W \ge w_{max}) = 2P(W \le w_{min}) \]

Normal Approximation for Large Samples

For large \(n\), the null distribution of \(W_+\) can be approximated by a normal distribution:

\[ z = \frac{w_+ - \frac{n(n+1)}{4} - \frac{1}{2}}{\sqrt{\frac{n(n+1)(2n+1)}{24}}} \]

The test rejects \(H_0\) at level \(\alpha\) if:

\[ w_+ \ge \frac{n(n+1)}{4} + \frac{1}{2} + z_{\alpha} \sqrt{\frac{n(n+1)(2n+1)}{24}} \approx w_{n,\alpha} \]

For a two-sided test, the decision rule uses the maximum or minimum of \(w_+\) and \(w_-\):

\(w_{max} = \max(w_+, w_-)\)

\(w_{min} = \min(w_+, w_-)\)

The p-value is computed as:

\[ p\text{-value} = 2P(W \ge w_{max}) = 2P(W \le w_{min}) \]

Handling Tied Ranks

If some observations \(|y_i|\) have tied absolute values, assign the average rank (or “midrank”) to all tied values. For example:

- Suppose \(y_1 = -1\), \(y_2 = 3\), \(y_3 = -3\), and \(y_4 = 5\).

- The ranks for \(|y_i|\) are:

- \(|y_1| = 1\): \(r_1 = 1\)

- \(|y_2| = |y_3| = 3\): \(r_2 = r_3 = \frac{2+3}{2} = 2.5\)

- \(|y_4| = 5\): \(r_4 = 4\)

# Example Data

data <- c(0.76, 0.82, 0.80, 0.79, 1.06, 0.83, -0.43, -0.34, 3.34, 2.33)

# Perform Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test (exact test)

wilcox_exact <- wilcox.test(data, exact = TRUE)

# Display results

wilcox_exact

#>

#> Wilcoxon signed rank exact test

#>

#> data: data

#> V = 52, p-value = 0.009766

#> alternative hypothesis: true location is not equal to 0For large samples, you can use the normal approximation by setting exact = FALSE:

# Perform Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test (normal approximation)

wilcox_normal <- wilcox.test(data, exact = FALSE)

# Display results

wilcox_normal

#>

#> Wilcoxon signed rank test with continuity correction

#>

#> data: data

#> V = 52, p-value = 0.01443

#> alternative hypothesis: true location is not equal to 04.3.7.3 Wald-Wolfowitz Runs Test

The Runs Test is a non-parametric test used to examine the randomness of a sequence. Specifically, it tests whether the order of observations in a sequence is random. This test is useful in detecting non-random patterns, such as trends, clustering, or periodicity.

The hypotheses for the Runs Test are:

- Null Hypothesis: \(H_0\): The sequence is random.

- Alternative Hypothesis: \(H_a\): The sequence is not random.

A run is a sequence of consecutive observations of the same type. For example: - In the binary sequence + + - - + - + +, there are 5 runs: ++, --, +, -, ++.

Runs can be formed based on any classification criteria, such as:

Positive vs. Negative values

Above vs. Below the median

Success vs. Failure in binary outcomes

Test Statistic

Number of Runs (\(R\)):

The observed number of runs in the sequence.-

Expected Number of Runs (\(E[R]\)):

Under the null hypothesis of randomness, the expected number of runs is: \[ E[R] = \frac{2 n_1 n_2}{n_1 + n_2} + 1 \] where:- \(n_1\): Number of observations in the first category (e.g., positives).

- \(n_2\): Number of observations in the second category (e.g., negatives).

- \(n = n_1 + n_2\): Total number of observations.

Variance of Runs (\(\text{Var}[R]\)):

The variance of the number of runs is given by: \[ \text{Var}[R] = \frac{2 n_1 n_2 (2 n_1 n_2 - n)}{n^2 (n - 1)} \]Standardized Test Statistic (\(z\)):

For large samples (\(n \geq 20\)), the test statistic is approximately normally distributed: \[ z = \frac{R - E[R]}{\sqrt{\text{Var}[R]}} \]

Decision Rule

- Compute the \(z\)-value and compare it to the critical value of the standard normal distribution.

- For a significance level \(\alpha\):

- Reject \(H_0\) if \(|z| \ge z_{\alpha/2}\) (two-sided test).

- Reject \(H_0\) if \(z \ge z_\alpha\) or \(z \le -z_\alpha\) for one-sided tests.

Steps for Conducting a Runs Test:

- Classify the data into two groups (e.g., above/below median, positive/negative).

- Count the total number of runs (\(R\)).

- Compute \(E[R]\) and \(\text{Var}[R]\) based on \(n_1\) and \(n_2\).

- Compute the \(z\)-value for the observed number of runs.

- Compare the \(z\)-value to the critical value to decide whether to reject \(H_0\).

For a numerical dataset where the test is based on values above and below the median:

# Example dataset

data <- c(1.2, -0.5, 3.4, -1.1, 2.8, -0.8, 4.5, 0.7)

library(randtests)

# Perform Runs Test (above/below median)

runs.test(data)

#>

#> Runs Test

#>

#> data: data

#> statistic = 2.2913, runs = 8, n1 = 4, n2 = 4, n = 8, p-value = 0.02195

#> alternative hypothesis: nonrandomnessThe output of the runs.test function includes:

Observed Runs: The actual number of runs in the sequence.

Expected Runs: The expected number of runs under \(H_0\).

p-value: The probability of observing a number of runs as extreme as the observed one under \(H_0\).

If the p-value is less than \(\alpha\), reject \(H_0\) and conclude that the sequence is not random.

Limitations of the Runs Test

The test assumes that observations are independent.

For small sample sizes, the test may have limited power.

Ties in the data must be resolved by a predefined rule (e.g., treating ties as belonging to one group or excluding them).

4.3.7.4 Quantile (or Percentile) Test

The Quantile Test (also called the Percentile Test) is a non-parametric test used to evaluate whether the proportion of observations falling within a specific quantile matches the expected proportion under the null hypothesis. This test is useful for assessing the distribution of data when specific quantiles (e.g., medians or percentiles) are of interest.

Suppose we want to test whether the true proportion of data below a specified quantile \(q\) matches a given probability \(p\). The hypotheses are:

- Null Hypothesis: \(H_0\): The true proportion is equal to \(p\).

- Alternative Hypothesis: \(H_a\): The true proportion is not equal to \(p\) (two-sided), greater than \(p\) (right-tailed), or less than \(p\) (left-tailed).

Test Statistic

The test statistic is based on the observed count of data points below the specified quantile.

Observed Count (\(k\)):

The number of data points \(y_i\) such that \(y_i \leq q\).Expected Count (\(E[k]\)):

The expected number of observations below the quantile \(q\) under \(H_0\) is: \[ E[k] = n \cdot p \]Variance:

Under the binomial distribution, the variance is: \[ \text{Var}[k] = n \cdot p \cdot (1 - p) \]Standardized Test Statistic (\(z\)):

For large \(n\), the test statistic is approximately normally distributed: \[ z = \frac{k - E[k]}{\sqrt{\text{Var}[k]}} = \frac{k - n \cdot p}{\sqrt{n \cdot p \cdot (1 - p)}} \]

Decision Rule

- Compute the \(z\)-value for the observed count.

- Compare the \(z\)-value to the critical value of the standard normal distribution:

- For a two-sided test, reject \(H_0\) if \(|z| \geq z_{\alpha/2}\).

- For a one-sided test, reject \(H_0\) if \(z \geq z_\alpha\) (right-tailed) or \(z \leq -z_\alpha\) (left-tailed).

Alternatively, calculate the p-value and reject \(H_0\) if the p-value \(\leq \alpha\).

Suppose we have a dataset and want to test whether the proportion of observations below the 50th percentile (median) matches the expected value of \(p = 0.5\).

# Example data

data <- c(12, 15, 14, 10, 13, 11, 14, 16, 15, 13)

# Define the quantile to test

quantile_value <- quantile(data, 0.5) # Median

p <- 0.5 # Proportion under H0

# Count observed values below or equal to the quantile

k <- sum(data <= quantile_value)

# Sample size

n <- length(data)

# Expected count under H0

expected_count <- n * p

# Variance

variance <- n * p * (1 - p)

# Test statistic (z-value)

z <- (k - expected_count) / sqrt(variance)

# Calculate p-value for two-sided test

p_value <- 2 * (1 - pnorm(abs(z)))

# Output results

list(

quantile_value = quantile_value,

observed_count = k,

expected_count = expected_count,

z_value = z,

p_value = p_value

)

#> $quantile_value

#> 50%

#> 13.5

#>

#> $observed_count

#> [1] 5

#>

#> $expected_count

#> [1] 5

#>

#> $z_value

#> [1] 0

#>

#> $p_value

#> [1] 1For a one-sided test (e.g., testing whether the proportion is greater than \(p\)):

# Calculate one-sided p-value

p_value_one_sided <- 1 - pnorm(z)

# Output one-sided p-value

p_value_one_sided

#> [1] 0.5Interpretation of Results

p-value: If the p-value is less than \(\alpha\), reject \(H_0\) and conclude that the proportion of observations below the quantile deviates significantly from \(p\).

Quantile Test Statistic (\(z\)): The \(z\)-value indicates how many standard deviations the observed count is from the expected count under the null hypothesis. Large positive or negative \(z\) values suggest non-random deviations.

Assumptions of the Test

Observations are independent.

The sample size is large enough for the normal approximation to the binomial distribution to be valid (\(n \cdot p \geq 5\) and \(n \cdot (1 - p) \geq 5\)).

Limitations of the Test

For small sample sizes, the normal approximation may not hold. In such cases, exact binomial tests are more appropriate.

The test assumes that the quantile used (e.g., the median) is well-defined and correctly calculated from the data.

4.4 Two-Sample Inference

4.4.1 For Means

Suppose we have two sets of observations:

- \(y_1, \dots, y_{n_y}\)

- \(x_1, \dots, x_{n_x}\)

These are random samples from two independent populations with means \(\mu_y\) and \(\mu_x\) and variances \(\sigma_y^2\) and \(\sigma_x^2\). Our goal is to compare \(\mu_y\) and \(\mu_x\) or test whether \(\sigma_y^2 = \sigma_x^2\).

4.4.1.1 Large Sample Tests

If \(n_y\) and \(n_x\) are large (\(\geq 30\)), the Central Limit Theorem allows us to make the following assumptions:

- Expectation: \[ E(\bar{y} - \bar{x}) = \mu_y - \mu_x \]

- Variance: \[ \text{Var}(\bar{y} - \bar{x}) = \frac{\sigma_y^2}{n_y} + \frac{\sigma_x^2}{n_x} \]

The test statistic is:

\[ Z = \frac{\bar{y} - \bar{x} - (\mu_y - \mu_x)}{\sqrt{\frac{\sigma_y^2}{n_y} + \frac{\sigma_x^2}{n_x}}} \sim N(0,1) \]

For large samples, replace variances with their unbiased estimators \(s_y^2\) and \(s_x^2\), yielding the same large sample distribution.

Confidence Interval

An approximate \(100(1-\alpha)\%\) confidence interval for \(\mu_y - \mu_x\) is:

\[ \bar{y} - \bar{x} \pm z_{\alpha/2} \sqrt{\frac{s_y^2}{n_y} + \frac{s_x^2}{n_x}} \]

Hypothesis Test

Testing:

\[ H_0: \mu_y - \mu_x = \delta_0 \quad \text{vs.} \quad H_a: \mu_y - \mu_x \neq \delta_0 \]

The test statistic:

\[ z = \frac{\bar{y} - \bar{x} - \delta_0}{\sqrt{\frac{s_y^2}{n_y} + \frac{s_x^2}{n_x}}} \]

Reject \(H_0\) at the \(\alpha\)-level if:

\[ |z| > z_{\alpha/2} \]

If \(\delta_0 = 0\), this tests whether the two means are equal.

# Large sample test

y <- c(10, 12, 14, 16, 18)

x <- c(9, 11, 13, 15, 17)

# Mean and variance

mean_y <- mean(y)

mean_x <- mean(x)

var_y <- var(y)

var_x <- var(x)

n_y <- length(y)

n_x <- length(x)

# Test statistic

z <- (mean_y - mean_x) / sqrt(var_y / n_y + var_x / n_x)

p_value <- 2 * (1 - pnorm(abs(z)))

list(z = z, p_value = p_value)

#> $z

#> [1] 0.5

#>

#> $p_value

#> [1] 0.61707514.4.1.2 Small Sample Tests

If the samples are small, assume the data come from independent normal distributions:

\(y_i \sim N(\mu_y, \sigma_y^2)\)

\(x_i \sim N(\mu_x, \sigma_x^2)\)

We can do inference based on the Student’s T Distribution, where we have 2 cases:

| Assumption | Tests | Plots |

|---|---|---|

| Independence and Identically Distributed (i.i.d.) Observations | Test for serial correlation | |

| Independence Between Samples | Correlation Coefficient | Scatterplot |

| Normality | See Normality Assessment | See Normality Assessment |

| Equality of Variances |

|

4.4.1.2.1 Equal Variances

Assumptions

- Independence and Identically Distributed (i.i.d.) Observations

Assume that observations in each sample are i.i.d., which implies:

\[ var(\bar{y}) = \frac{\sigma^2_y}{n_y}, \quad var(\bar{x}) = \frac{\sigma^2_x}{n_x} \]

- Independence Between Samples

The samples are assumed to be independent, meaning no observation from one sample influences observations from the other. This independence allows us to write:

\[ \begin{aligned} var(\bar{y} - \bar{x}) &= var(\bar{y}) + var(\bar{x}) - 2cov(\bar{y}, \bar{x}) \\ &= var(\bar{y}) + var(\bar{x}) \\ &= \frac{\sigma^2_y}{n_y} + \frac{\sigma^2_x}{n_x} \end{aligned} \]

This calculation assumes \(cov(\bar{y}, \bar{x}) = 0\) due to the independence between the samples.

- Normality Assumption

We assume that the underlying populations are normally distributed. This assumption justifies the use of the Student’s T Distribution, which is critical for hypothesis testing and constructing confidence intervals.

- Equality of Variances

If the population variances are equal, i.e., \(\sigma^2_y = \sigma^2_x = \sigma^2\), then \(s^2_y\) and \(s^2_x\) are both unbiased estimators of \(\sigma^2\). This allows us to pool the variances.

The pooled variance estimator is calculated as:

\[ s^2 = \frac{(n_y - 1)s^2_y + (n_x - 1)s^2_x}{(n_y - 1) + (n_x - 1)} \]

The pooled variance estimate has degrees of freedom equal to:

\[ df = (n_y + n_x - 2) \]

Test Statistic

The test statistic is: \[ T = \frac{\bar{y} - \bar{x} - (\mu_y - \mu_x)}{s \sqrt{\frac{1}{n_y} + \frac{1}{n_x}}} \sim t_{n_y + n_x - 2} \]

Confidence Interval

A \(100(1 - \alpha)\%\) confidence interval for \(\mu_y - \mu_x\) is: \[ \bar{y} - \bar{x} \pm t_{n_y + n_x - 2, \alpha/2} \cdot s \sqrt{\frac{1}{n_y} + \frac{1}{n_x}} \]

Hypothesis Test

Testing: \[ H_0: \mu_y - \mu_x = \delta_0 \quad \text{vs.} \quad H_a: \mu_y - \mu_x \neq \delta_0 \]

Reject \(H_0\) if: \[ |T| > t_{n_y + n_x - 2, \alpha/2} \]

# Small sample test with equal variance

t_test_equal <- t.test(y, x, var.equal = TRUE)

t_test_equal

#>

#> Two Sample t-test

#>

#> data: y and x

#> t = 0.5, df = 8, p-value = 0.6305

#> alternative hypothesis: true difference in means is not equal to 0

#> 95 percent confidence interval:

#> -3.612008 5.612008

#> sample estimates:

#> mean of x mean of y

#> 14 134.4.1.2.2 Unequal Variances

Assumptions

- Independence and Identically Distributed (i.i.d.) Observations

Assume that observations in each sample are i.i.d., which implies:

\[ var(\bar{y}) = \frac{\sigma^2_y}{n_y}, \quad var(\bar{x}) = \frac{\sigma^2_x}{n_x} \]

- Independence Between Samples

The samples are assumed to be independent, meaning no observation from one sample influences observations from the other. This independence allows us to write:

\[ \begin{aligned} var(\bar{y} - \bar{x}) &= var(\bar{y}) + var(\bar{x}) - 2cov(\bar{y}, \bar{x}) \\ &= var(\bar{y}) + var(\bar{x}) \\ &= \frac{\sigma^2_y}{n_y} + \frac{\sigma^2_x}{n_x} \end{aligned} \]

This calculation assumes \(cov(\bar{y}, \bar{x}) = 0\) due to the independence between the samples.

- Normality Assumption

We assume that the underlying populations are normally distributed. This assumption justifies the use of the Student’s T Distribution, which is critical for hypothesis testing and constructing confidence intervals.

- Unequal Variances

\(\sigma_y^2 \neq \sigma_x^2\)

Test Statistic

The test statistic is:

\[ T = \frac{\bar{y} - \bar{x} - (\mu_y - \mu_x)}{\sqrt{\frac{s_y^2}{n_y} + \frac{s_x^2}{n_x}}} \]

Degrees of Freedom (Welch-Satterthwaite Approximation) (Satterthwaite 1946)

The degrees of freedom are approximated by:

\[ v = \frac{\left(\frac{s_y^2}{n_y} + \frac{s_x^2}{n_x}\right)^2}{\frac{\left(\frac{s_y^2}{n_y}\right)^2}{n_y - 1} + \frac{\left(\frac{s_x^2}{n_x}\right)^2}{n_x - 1}} \]

Since \(v\) is fractional, truncate to the nearest integer.

Confidence Interval

A \(100(1 - \alpha)\%\) confidence interval for \(\mu_y - \mu_x\) is:

\[ \bar{y} - \bar{x} \pm t_{v, \alpha/2} \sqrt{\frac{s_y^2}{n_y} + \frac{s_x^2}{n_x}} \]

Hypothesis Test

Testing:

\[ H_0: \mu_y - \mu_x = \delta_0 \quad \text{vs.} \quad H_a: \mu_y - \mu_x \neq \delta_0 \]

Reject \(H_0\) if:

\[ |T| > t_{v, \alpha/2} \]

where

\[ t = \frac{\bar{y} - \bar{x}-\delta_0}{\sqrt{s^2_y/n_y + s^2_x /n_x}} \]

# Small sample test with unequal variance

t_test_unequal <- t.test(y, x, var.equal = FALSE)

t_test_unequal

#>

#> Welch Two Sample t-test

#>

#> data: y and x

#> t = 0.5, df = 8, p-value = 0.6305

#> alternative hypothesis: true difference in means is not equal to 0

#> 95 percent confidence interval:

#> -3.612008 5.612008

#> sample estimates:

#> mean of x mean of y

#> 14 134.4.2 For Variances

To compare the variances of two independent samples, we can use the F-test. The test statistic is defined as:

\[ F_{ndf,ddf} = \frac{s_1^2}{s_2^2} \]

where \(s_1^2 > s_2^2\), \(ndf = n_1 - 1\), and \(ddf = n_2 - 1\) are the numerator and denominator degrees of freedom, respectively.

4.4.2.1 F-Test

The hypotheses for the F-test are:

\[ \begin{aligned} H_0&: \sigma_y^2 = \sigma_x^2 \quad \text{(equal variances)} \\ H_a&: \sigma_y^2 \neq \sigma_x^2 \quad \text{(unequal variances)} \end{aligned} \]

The test statistic is:

\[ F = \frac{s_y^2}{s_x^2} \]

where \(s_y^2\) and \(s_x^2\) are the sample variances of the two groups.

Decision Rule

Reject \(H_0\) if:

\(F > F_{n_y-1, n_x-1, \alpha/2}\) (upper critical value), or

\(F < F_{n_y-1, n_x-1, 1-\alpha/2}\) (lower critical value).

Here:

- \(F_{n_y-1, n_x-1, \alpha/2}\) and \(F_{n_y-1, n_x-1, 1-\alpha/2}\) are the critical points of the F-distribution, with \(n_y - 1\) and \(n_x - 1\) degrees of freedom.

Assumptions

- The F-test requires that the data in both groups follow a normal distribution.

- The F-test is sensitive to deviations from normality (e.g., heavy-tailed distributions). If the normality assumption is violated, it may lead to an inflated Type I error rate (false positives).

Limitations and Alternatives

-

Sensitivity to Non-Normality:

- When data have long-tailed distributions (positive kurtosis), the F-test may produce misleading results.

- To assess normality, see Normality Assessment.

-

Nonparametric Alternatives:

- If the normality assumption is not met, use robust tests such as the Modified Levene Test (Brown-Forsythe Test), which compares group variances based on medians instead of means.

# Load iris dataset

data(iris)

# Subset data for two species

irisVe <- iris$Petal.Width[iris$Species == "versicolor"]

irisVi <- iris$Petal.Width[iris$Species == "virginica"]

# Perform F-test

f_test <- var.test(irisVe, irisVi)

# Display results

f_test

#>

#> F test to compare two variances

#>

#> data: irisVe and irisVi

#> F = 0.51842, num df = 49, denom df = 49, p-value = 0.02335

#> alternative hypothesis: true ratio of variances is not equal to 1

#> 95 percent confidence interval:

#> 0.2941935 0.9135614

#> sample estimates:

#> ratio of variances

#> 0.51842434.4.2.2 Levene’s Test

Levene’s Test is a robust method for testing the equality of variances across multiple groups. Unlike the F-test, it is less sensitive to departures from normality and is particularly useful for handling non-normal distributions and datasets with outliers. The test works by analyzing the deviations of individual observations from their group mean or median.

Test Procedure

- Compute the absolute deviations of each observation from its group mean or median:

- For group \(y\): \[ d_{y,i} = |y_i - \text{Central Value}_y| \]

- For group \(x\): \[ d_{x,j} = |x_j - \text{Central Value}_x| \]

- The “central value” can be either the mean (classic Levene’s test) or the median (Modified Levene Test (Brown-Forsythe Test) variation, more robust for non-normal data).

- Perform a one-way ANOVA on the absolute deviations to test for differences in group variances.

Hypotheses

- Null Hypothesis (\(H_0\)): All groups have equal variances.

- Alternative Hypothesis (\(H_a\)): At least one group has a variance different from the others.

Test Statistic

The Levene test statistic is calculated as an ANOVA on the absolute deviations. Let:

\(k\): Number of groups,

\(n_i\): Number of observations in group \(i\),

\(n\): Total number of observations.

The test statistic is:

\[ W = \frac{(n - k) \sum_{i=1}^k n_i (\bar{d}_i - \bar{d})^2}{(k - 1) \sum_{i=1}^k \sum_{j=1}^{n_i} (d_{i,j} - \bar{d}_i)^2} \]

where:

\(d_{i,j}\): Absolute deviations within group \(i\),

\(\bar{d}_i\): Mean of the absolute deviations for group \(i\),

\(\bar{d}\): Overall mean of the absolute deviations.

Under the null hypothesis, \(W \sim F_{k-1, n - k}\).

Decision Rule

- Compute the test statistic \(W\).

- Reject \(H_0\) at significance level \(\alpha\) if: \[ W > F_{k-1, n-k, \alpha} \]

# Load required package

library(car)

# Perform Levene's Test (absolute deviations from the mean)

levene_test_mean <- leveneTest(Petal.Width ~ Species, data = iris)

# Perform Levene's Test (absolute deviations from the median)

levene_test_median <-

leveneTest(Petal.Width ~ Species, data = iris, center = median)

# Display results

levene_test_mean

#> Levene's Test for Homogeneity of Variance (center = median)

#> Df F value Pr(>F)

#> group 2 19.892 2.261e-08 ***

#> 147

#> ---

#> Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

levene_test_median

#> Levene's Test for Homogeneity of Variance (center = median)

#> Df F value Pr(>F)

#> group 2 19.892 2.261e-08 ***

#> 147

#> ---

#> Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1The output includes:

Df: Degrees of freedom for the numerator and denominator.

F-value: The computed value of the test statistic \(W\).

p-value: The probability of observing such a value under the null hypothesis.

If the p-value is less than \(\alpha\), reject \(H_0\) and conclude that the group variances are significantly different.

Otherwise, fail to reject \(H_0\) and conclude there is no evidence of a difference in variances.

Advantages of Levene’s Test

-

Robustness:

- Handles non-normal data and outliers better than the F-test.

-

Flexibility:

-

By choosing the center value (mean or median), it can adapt to different data characteristics:

Use the mean for symmetric distributions.

Use the median for non-normal or skewed data.

-

-

Versatility:

- Applicable to comparing variances across more than two groups, unlike the Modified Levene Test (Brown-Forsythe Test), which is limited to two groups.

4.4.2.3 Modified Levene Test (Brown-Forsythe Test)

The Modified Levene Test is a robust alternative to the F-test for comparing variances between two groups. Instead of using squared deviations (as in the F-test), this test considers the absolute deviations from the median, making it less sensitive to non-normal data and long-tailed distributions. It is, however, still appropriate for normally distributed data.

For each sample, compute the absolute deviations from the median:

\[ d_{y,i} = |y_i - y_{.5}| \quad \text{and} \quad d_{x,i} = |x_i - x_{.5}| \]

Let:

- \(\bar{d}_y\) and \(\bar{d}_x\) be the means of the absolute deviations for groups \(y\) and \(x\), respectively.

The test statistic is:

\[ t_L^* = \frac{\bar{d}_y - \bar{d}_x}{s \sqrt{\frac{1}{n_y} + \frac{1}{n_x}}} \]

where the pooled variance \(s^2\) is:

\[ s^2 = \frac{\sum_{i=1}^{n_y} (d_{y,i} - \bar{d}_y)^2 + \sum_{j=1}^{n_x} (d_{x,j} - \bar{d}_x)^2}{n_y + n_x - 2} \]

Assumptions

Constant Variance of Error Terms:

The test assumes equal error variances in each group under the null hypothesis.Moderate Sample Size:

The approximation \(t_L^* \sim t_{n_y + n_x - 2}\) holds well for moderate or large sample sizes.

Decision Rule

- Compute \(t_L^*\) using the formula above.

- Reject the null hypothesis of equal variances if: \[ |t_L^*| > t_{n_y + n_x - 2; \alpha/2} \]

This is equivalent to applying a two-sample t-test to the absolute deviations.

# Absolute deviations from the median

dVe <- abs(irisVe - median(irisVe))

dVi <- abs(irisVi - median(irisVi))

# Perform t-test on absolute deviations

levene_test <- t.test(dVe, dVi, var.equal = TRUE)

# Display results

levene_test

#>

#> Two Sample t-test

#>

#> data: dVe and dVi

#> t = -2.5584, df = 98, p-value = 0.01205

#> alternative hypothesis: true difference in means is not equal to 0

#> 95 percent confidence interval:

#> -0.12784786 -0.01615214

#> sample estimates:

#> mean of x mean of y

#> 0.154 0.226For small sample sizes, use the unequal variance t-test directly on the original data as a robust alternative:

# Small sample t-test with unequal variances

small_sample_test <- t.test(irisVe, irisVi, var.equal = FALSE)

# Display results

small_sample_test

#>

#> Welch Two Sample t-test

#>

#> data: irisVe and irisVi

#> t = -14.625, df = 89.043, p-value < 2.2e-16

#> alternative hypothesis: true difference in means is not equal to 0

#> 95 percent confidence interval:

#> -0.7951002 -0.6048998

#> sample estimates:

#> mean of x mean of y

#> 1.326 2.0264.4.2.4 Bartlett’s Test

The Bartlett’s Test is a statistical procedure for testing the equality of variances across multiple groups. It assumes that the data in each group are normally distributed and is sensitive to deviations from normality. When the assumption of normality holds, Bartlett’s Test is more powerful than Levene’s Test.

Hypotheses for Bartlett’s Test

- Null Hypothesis (\(H_0\)): All groups have equal variances.

- Alternative Hypothesis (\(H_a\)): At least one group has a variance different from the others.

The test statistic for Bartlett’s Test is:

\[ B = \frac{(n - k) \log(S_p^2) - \sum_{i=1}^k (n_i - 1) \log(S_i^2)}{1 + \frac{1}{3(k - 1)} \left( \sum_{i=1}^k \frac{1}{n_i - 1} - \frac{1}{n - k} \right)} \]

Where:

\(k\): Number of groups,

\(n_i\): Number of observations in group \(i\),

\(n = \sum_{i=1}^k n_i\): Total number of observations,

\(S_i^2\): Sample variance of group \(i\),

\(S_p^2\): Pooled variance, given by: \[ S_p^2 = \frac{\sum_{i=1}^k (n_i - 1) S_i^2}{n - k} \]

Under the null hypothesis, the test statistic \(B \sim \chi^2_{k - 1}\).

Assumptions

- Normality: The data in each group must follow a normal distribution.

- Independence: Observations within and between groups must be independent.

- Equal Sample Sizes (Optional): Bartlett’s Test is more robust if sample sizes are approximately equal.

Decision Rule

- Compute the test statistic \(B\).

- Compare \(B\) to the critical value of the Chi-Square distribution at \(\alpha\) and \(k - 1\) degrees of freedom.

- Reject \(H_0\) if: \[ B > \chi^2_{k-1, \alpha} \]

Alternatively, use the p-value:

- Reject \(H_0\) if the p-value \(\leq \alpha\).

# Perform Bartlett's Test

bartlett_test <- bartlett.test(Petal.Width ~ Species, data = iris)

# Display results

bartlett_test

#>

#> Bartlett test of homogeneity of variances

#>

#> data: Petal.Width by Species

#> Bartlett's K-squared = 39.213, df = 2, p-value = 3.055e-09The output includes:

Bartlett’s K-squared: The value of the test statistic \(B\).

df: Degrees of freedom (\(k - 1\)), where \(k\) is the number of groups.

p-value: The probability of observing such a value of \(B\) under \(H_0\).

If the p-value is less than \(\alpha\), reject \(H_0\) and conclude that the variances are significantly different across groups.

If the p-value is greater than \(\alpha\), fail to reject \(H_0\) and conclude that there is no significant evidence of variance differences.

Limitations of Bartlett’s Test

Sensitivity to Non-Normality:

Bartlett’s Test is highly sensitive to departures from normality. Even slight deviations can lead to misleading results.Not Robust to Outliers:

Outliers can disproportionately affect the test result.-

Alternatives:

If the normality assumption is violated, use robust alternatives like:Levene’s Test (absolute deviations)

Modified Levene Test (Brown-Forsythe Test) (median-based absolute deviations)

Advantages of Bartlett’s Test

High Power: Bartlett’s Test is more powerful than robust alternatives when the normality assumption holds.

Simple Implementation: The test is easy to perform and interpret.

4.4.3 Power

To evaluate the power of a test, we consider the situation where the variances are equal across groups:

\[ \sigma_y^2 = \sigma_x^2 = \sigma^2 \]

Under the assumption of equal variances, we take equal sample sizes from both groups, i.e., \(n_y = n_x = n\).

Hypotheses for One-Sided Testing

We are testing:

\[ H_0: \mu_y - \mu_x \leq 0 \quad \text{vs.} \quad H_a: \mu_y - \mu_x > 0 \]

Test Statistic

The \(\alpha\)-level z-test rejects \(H_0\) if the test statistic:

\[ z = \frac{\bar{y} - \bar{x}}{\sigma \sqrt{\frac{2}{n}}} > z_\alpha \]

where:

\(\bar{y}\) and \(\bar{x}\) are the sample means,

\(\sigma\) is the common standard deviation,

\(z_\alpha\) is the critical value from the standard normal distribution.

Power Function

The power of the test, denoted as \(\pi(\mu_y - \mu_x)\), is the probability of correctly rejecting \(H_0\) when \(\mu_y - \mu_x\) is some specified value. Under the alternative hypothesis, the power function is:

\[ \pi(\mu_y - \mu_x) = \Phi\left(-z_\alpha + \frac{\mu_y - \mu_x}{\sigma} \sqrt{\frac{n}{2}}\right) \]

where:

\(\Phi\) is the cumulative distribution function (CDF) of the standard normal distribution,

\(\frac{\mu_y - \mu_x}{\sigma} \sqrt{\frac{n}{2}}\) represents the standardized effect size.

Determining the Required Sample Size

To achieve a desired power of \(1 - \beta\) when the true difference is \(\delta\) (the smallest difference of interest), we solve for the required sample size \(n\). The power equation is:

\[ \Phi\left(-z_\alpha + \frac{\delta}{\sigma} \sqrt{\frac{n}{2}}\right) = 1 - \beta \]

Rearranging for \(n\), the required sample size is:

\[ n = \frac{2 \sigma^2}{\delta^2} \left(z_\alpha + z_\beta\right)^2 \]

where:

\(\sigma\): The common standard deviation,

\(z_{\alpha}\): The critical value for the Type I error rate \(\alpha\) (one-sided test),

\(z_{\beta}\): The critical value for the Type II error rate \(\beta\) (related to power \(1 - \beta\)),

\(\delta\): The minimum detectable difference between the means.

# Parameters

alpha <- 0.05 # Significance level

beta <- 0.2 # Type II error rate (1 - Power = 0.2)

sigma <- 1 # Common standard deviation

delta <- 0.5 # Minimum detectable difference

# Critical values

z_alpha <- qnorm(1 - alpha)

z_beta <- qnorm(1 - beta)

# Sample size calculation

n <- (2 * sigma ^ 2 * (z_alpha + z_beta) ^ 2) / delta ^ 2

# Output the required sample size (per group)

ceiling(n)

#> [1] 50Sample Size for Two-Sided Tests

For a two-sided test, replace \(z_{\alpha}\) with \(z_{\alpha/2}\) to account for the two-tailed critical region:

\[ n = 2 \left( \frac{\sigma (z_{\alpha/2} + z_{\beta})}{\delta} \right)^2 \]

This ensures that the test has the required power \(1 - \beta\) to detect a difference of size \(\delta\) between the means at significance level \(\alpha\).

Adjustment for the Exact t-Test

When conducting an exact two-sample t-test for small sample sizes, the sample size calculation involves the non-central t-distribution. An approximate correction can be applied using the critical values from the t-distribution instead of the z-distribution.

The adjusted sample size is:

\[ n^* = 2 \left( \frac{\sigma (t_{2n-2; \alpha/2} + t_{2n-2; \beta})}{\delta} \right)^2 \]

Where:

\(t_{2n-2; \alpha/2}\): The critical value for the t-distribution with \(2n - 2\) degrees of freedom for significance level \(\alpha/2\),

\(t_{2n-2; \beta}\): The critical value for the t-distribution with \(2n - 2\) degrees of freedom for power \(1 - \beta\).

This correction adjusts for the increased variability of the t-distribution, especially important for small sample sizes.

# Parameters

alpha <- 0.05 # Significance level

power <- 0.8 # Desired power

sigma <- 1 # Common standard deviation

delta <- 0.5 # Minimum detectable difference

# Calculate sample size for two-sided test

sample_size <-

power.t.test(

delta = delta,

sd = sigma,

sig.level = alpha,

power = power,

type = "two.sample",

alternative = "two.sided"

)

# Display results

sample_size

#>

#> Two-sample t test power calculation

#>

#> n = 63.76576

#> delta = 0.5

#> sd = 1

#> sig.level = 0.05

#> power = 0.8

#> alternative = two.sided

#>

#> NOTE: n is number in *each* groupKey Insights

Z-Test vs. T-Test:

For large samples, the normal approximation (z-test) works well. For small samples, the t-test correction using the t-distribution is essential.-

Effect of Power and Significance Level:

Increasing power (\(1 - \beta\)) or decreasing \(\alpha\) requires larger sample sizes.

A smaller minimum detectable difference (\(\delta\)) also requires a larger sample size.

Two-Sided Tests:

Two-sided tests require larger sample sizes compared to one-sided tests due to the split critical region.

Formula Summary

| Test Type | Formula for Sample Size |

|---|---|

| One-Sided Test | \(n = 2 \left( \frac{\sigma (z_{\alpha} + z_{\beta})}{\delta} \right)^2\) |