16 Numbers and factors

Seeing numbers in a data file usually seems straightforward. However, erroneous interpretations of numeric information are among the most common errors for inexperienced data analysts.

The two key topics (and corresponding R packages) of this chapter are:

numbers (and their representations)

factors (to handle categorical variables)

Please note: This chapter contains useful notes, but is yet to be finished.

16.1 Introduction

Many people struggle with numeric calculations. However, even people who excel in manipulating numbers tend to overlook their representational properties.

When thinking about the representation of numbers, even simple numbers become surprisingly complicated. This is mostly due to our intimate familarity with particular forms of representation, which are quite arbitrary. When stripping away our implicit assumptions, numbers are quite complex representational constructs.

Main distinctions: Numbers as numeric values vs. as ranks vs. as (categorical) labels.

Example: How tall is someone?

Distinguish between issues of judgment vs. measurement.

When providing a quantitative value, the same measurement can be made (mapped to, represented) on different scales:

size in cm: comparisons between values are scaled (e.g., 20% larger, etc.)

rank within group: comparisons between people are possible, but no longer scaled

categories: can be ordered (small-medium-tall) or unordered (fits vs. does not fit)

Additionally, any height value can be expressed in different ways:

- units: 180cm in ft?

- accuracy: rounding

- number system: “ten” vs. “zehn”, value \(10\) as “1010”” in binary system

Why is this relevant? Distinguish between the meaning and representation of objects:

- Different uses of numbers allow different types of calculations and tests.

- They should be assigned to different data types.

16.2 Essentials

Important aspects:

Different types of numbers: integers vs. doubles

Numbers as values vs. their name/description/representation (as strings of symbols/digits/numerals).

Some numbers are used to denote categories (identity and difference, but not magnitude/value).

16.3 Numbers

We typically think we know numbers. However, we typically deal with numbers that are represented in a specific numeral system. Our familiarity with specific numeral systems obscures our dependency on arbitrary conventions.

16.3.1 Types of numbers

Different types of numbers (integers vs. doubles):

- integers

- positive vs. negative

- decimals, fractions

- real numbers

Consider some oddities:

- integers

- errors due to floating point (im-)precision

Also relevant: Rules for rounding and scaling numbers.

16.3.2 Representing numbers

When reading a number (like \(123\)), we tend to overlook that this number is represented in a particular notational system. Technically, we need to distinguish between the numeric value \(123\) and the character string of numerical symbols (aka. digits or numerals) “123”.

Generally, numbers are represented according to notational conventions: Strings of dedicated symbols (e.g., Arabic numeral digits 0–9), to be interpreted according to rules (e.g., positional systems require expansion of polynomials).

Overall, our decimal system is a compromise (between more divisible and more unique bases) and a matter of definition. Importantly, our way of representing numbers is subject to two arbitrary conventions:

a positional system with a base value of 10,

representing unit values by the numeral symbols/digits 0–9.

Only changing 2. (by replacing familiar digits with arbitrary symbols) renders simple calculations much more difficult (see letter arithmetic problems).

In the following, we will preserve 2. (the digits and their meaning), but change the base value. This illustrates the difference between numeric value and their symbolic representation (as a string of numeric symbols/digits). (We only cover natural numbers, as they are complicated enough.)

Example

The digits “123” only denote the value of \(123\) in the Hindu-Arabic positional system with a decimal base (i.e., base 10 and numeric symbols 0–9).

Positional notation: Given \(n\) digits \(d_i\) and a base \(b\), a number’s numeric value \(v\) is given by expanding a polynomial sum:

\[v = \sum_{i=1}^{n} {d_i \cdot b^{i-1}}\]

with \(i\) representing each digit’s position (from right to left). Thus, the number \(123\) is a representational shortcut for

\[v = (3 \cdot 10^0) + (2 \cdot 10^1) + (1 \cdot 10^2) = 3 + 20 + 100\]

Representing numbers as base \(b\) positional system

Just like “ten” and “zehn” are two different ways for denoting the same value (\(10\)), we can write a given value in different notations. A simple way of showing this is to use positional number systems with different base values \(b\). As long as \(b \leq 10\), we do not need any new digit symbols (but note that the value of a digit must never exceed the base value).

Note two consequences:

The same symbol string represents different numeric values in different notations:

The digit string “11” happens to represent a value of \(11\) in base-10 notation. However, the same digit string “11” represents a value of \(6\) in base-5 notation, and a value of \(3\) in base-2 notation.The same numeric value is represented differently in different notations:

A given numeric value of \(11\) is written as “11” in decimal notation, but can alternatively be written as “1011” in base-2, “102” in base-3, and “12” in base-9 notation.

Examples of alternative number systems

Alternatives to the base-10 positional system are not just an academic exercise. See

- binary number systems (see Wikipedia: Binary number)

- hexadecimal numbers (see Wikipedia: Hexadecimal)

Examples in R

Viewing numbers as symbol strings (of digits): Formatting numbers (e.g., in text or tables)

-

num_as_char()from the ds4psy package:

ds4psy::num_as_char(1:10, n_pre_dec = 2, n_dec = 0)

#> [1] "01" "02" "03" "04" "05" "06" "07" "08" "09" "10"Note the comma() function of the scales package.

-

base2dec()from the ds4psy package:

ds4psy::base2dec("11")

#> [1] 3

ds4psy::base2dec("111")

#> [1] 7

ds4psy::base2dec("100", base = 5)

#> [1] 25Demonstration: Show a similation that converts from decimal to another base and back:

| n_org | base | n_base | n_dec |

|---|---|---|---|

| 409 | 15 | 1C4 | 409 |

| 798 | 48 | GU | 798 |

| 6340 | 4 | 1203010 | 6340 |

| 7179 | 18 | 142F | 7179 |

| 7548 | 60 | 25m | 7548 |

| 6252 | 6 | 44540 | 6252 |

| 3759 | 10 | 3759 | 3759 |

| 6676 | 58 | 1v6 | 6676 |

| 7605 | 8 | 16665 | 7605 |

| 3774 | 58 | 174 | 3774 |

| 4546 | 15 | 1531 | 4546 |

| 542 | 38 | EA | 542 |

| 9556 | 8 | 22524 | 9556 |

| 8973 | 50 | 3TN | 8973 |

| 3390 | 2 | 110100111110 | 3390 |

| 5426 | 53 | 1nK | 5426 |

| 4473 | 54 | 1Sj | 4473 |

| 995 | 57 | HQ | 995 |

| 3116 | 24 | 59K | 3116 |

| 1681 | 42 | e1 | 1681 |

See 13 Numbers of r4ds (Wickham, Çetinkaya-Rundel, et al., 2023).

16.3.3 Logical values

The simplest numbers are not even numbers, but the truth values TRUE vs. FALSE.

R uses a convention:

In arithmetic expressions, TRUE and FALSE are interpreted as 1 (presence) and 0 (absence), respectively.

This can easily be explored and verified:

TRUE + FALSE

#> [1] 1

TRUE - FALSE

#> [1] 1

TRUE * FALSE

#> [1] 0

TRUE / FALSE

#> [1] InfHowever, the last example shows that we must be careful (e.g., watch out for divisions by zero) should probably not overdo it.

Reasons for this convention: Logical indexing, getting the sums and means of indices. Example:

(age <- sample(1:80, size = 20, replace = TRUE))

#> [1] 78 9 7 3 43 54 50 11 14 80 2 54 68 50 16 71 67 52 31 28

# Age values of adults:

(age_adults <- age[age >= 18])

#> [1] 78 43 54 50 80 54 68 50 71 67 52 31 28

length(age_adults)

#> [1] 13

# Arithmetic with logical values:

sum(age >= 18) # How many adults?

#> [1] 13

mean(age >= 18) # Proportion of adults?

#> [1] 0.65Pitfalls of logical values: Using T and F as abbreviations of TRUE and FALSE.

As the documentation of logical() spells out:

TRUEandFALSEare reserved words denoting logical constants in the R language,

whereasTandFare global variables whose initial values set to these.

All four arelogical(1)vectors.

16.3.4 Integers

Oddity: See is.integer() vs. is_wholenumber()

16.3.7 Rounding

Statistical computations are often more precise than what is warranted by the data.

For instance, when a sample contains \(N=100\) individuals, some variable (e.g., their height in cm) may average to a numeric value of 178.1234, but if that variable was measured in integers, it does not make sense to provide more than two digits (as an increasing a raw value by \(1\) would change the mean by \(.01\)).

To adjust the precision of a number, we can use round(x) to round a number x to some number of digits.

round(178.1234) # nearest integer (digits = 0)

#> [1] 178

round(178.1234, digits = 1)

#> [1] 178.1

round(178.1234, digits = 2)

#> [1] 178.12By providing negative values to digits, we can round to the nearest multiple of 10, 100, etc.:

round(178.1234, digits = -1) # nearest 10

#> [1] 180

round(178.1234, digits = -2) # nearest 100

#> [1] 200Most people are surprised by the result of the following rounding operation:

(v <- -5:5 + .50)

#> [1] -4.5 -3.5 -2.5 -1.5 -0.5 0.5 1.5 2.5 3.5 4.5 5.5

round(v)

#> [1] -4 -4 -2 -2 0 0 2 2 4 4 6There is actually a good reason for this seemingly strange behavior:

round() uses so-called Banker’s rounding, also known as “round half to even” (and recommended by IEEE / IEC):

Any number half way between two integers will be rounded to the even integer.

This way, half of the .50 are rounded down, the other half is rounded up, keeping the rounded set unbiased (assuming both cases occur equally often).

If we wanted to force R to always round down or up, we can use the floor() and ceiling() functions, respectively:

As these functions do not have a digits argument, we can adjust the precision of their results by scaling their arguments:

x <- .345

# Scale to nearest decimal (.10):

.10 * floor(x/.10)

#> [1] 0.3

.10 * ceiling(x/.10)

#> [1] 0.4

# Scale to nearest percent (.01):

.01 * floor(x/.01)

#> [1] 0.34

.01 * ceiling(x/.01)

#> [1] 0.35The same scaling-method allows rounding numbers to the nearest multiple of another number:

16.3.9 Using logarithms

Example from McElreath (2018) (Chapter 1, R code 0.3):

The following expressions are mathematically identical

\(p_{1} = \text{log}(.01^{200})\) \(p_{2} = 200 \cdot \text{log}(.01)\)

but R computes two different solutions:

The value of p_2 (i.e., -921.0340372) is correct. The discrepancy to p_1 is due to rounding, where very small decimal values are rounded to zero and log(0) is -\infty{}. Obviously, such rounding issues can introduce substantial errors. To prevent such errors, expert modelers often perform statistical calculations on the logarithm of probabilities, rather than the probability values themselves.

16.4 Factors

See McNamara & Horton (2018) and 16 Factors of r4ds (Wickham, Çetinkaya-Rundel, et al., 2023).

Encoding categorical data presents specific challenges, but is relevant because many variables are inherently categorical in nature (e.g., gender, blood type, dress size, tax bracket, city, or state). As categorical data can be encoded as text strings (i.e., of type “character” in R) or as numbers, it often remains unnoticed that factors provide an alternative way of dealing with them.

R’s way of encoding categorical data are factors. As many users have a poor understanding of them and may even inadvertently use them, they have a bad reputation. However, they are often useful for representing variables that feature a small and fixed number of categories (e.g., S/M/L; female/male/other) or an ordered number of instances (e.g., days of the week, months). In statistics, factors allow testing for specific effects (e.g., comparing the results of several treatments with those of a control condition).

Categorical data could be represented as numbers, text strings, or as factors.

Example: Gender as “male” vs. “female”. But any survey with more than a few people will require additional categories, like “other” or “do not wish to respond”.

Factors are useful and indispensable (for graphing, statistical analysis), but additional complexity increases chance of unexpected behavior and pitfalls.

Factors are used when variables denote categories or groups. Specific reasons for using factors:

- for defining experimental conditions

- for ordered categories (e.g., in graphs)

16.4.1 Basics

Different factor values are internally represented as integers. This may occasionally seem confusing:

A neat example of potentially unexpected behavior of factors from McNamara & Horton (2018) (p. 98):

x_org <- c(10, 20, 10, 100, 50)

x_fct <- factor(x_org)

x_fcn <- as.numeric(x_fct)

# Compare (as df):

knitr::kable(data.frame(x_org, x_fct, x_fcn),

caption = "Turning a numeric variable into a factor and back...")| x_org | x_fct | x_fcn |

|---|---|---|

| 10 | 10 | 1 |

| 20 | 20 | 2 |

| 10 | 10 | 1 |

| 100 | 100 | 4 |

| 50 | 50 | 3 |

When only comparing x_org and x_fct, it seems as converting x_org into a factor had not changed anything.

However, when using the base R function as.numeric() on x_fct, we do not recover the original numeric values, but instead yields the values of x_fcn.

Instead, we realize that the factor() function mapped the values of x_org to integer values (from 1 to 4) and used the original values as the labels of factor levels.

Thus, recovering numeric values from numeric factor variables may yield unexpected results.

A similar surprise may occur when starting with a character object:

as.numeric("txt")

#> [1] NA

as.numeric(factor("txt"))

#> [1] 1Here, coercing as.numeric("txt") into a missing (NA) value makes perfect sense. However, turning txt into a factor dutifully reports its first level as txt, but internally used the number 1 to encode the first factor level.

Due to unexpected behaviors like this, it recently became unfashionable to automatically convert text variables into factors (e.g., the default read.*() functions have been changed to use stringAsFactors = FALSE).

But as many statistical tasks still require index variables (e.g., to denote reference groups), handling factors is still an important and useful skill.

16.5 Conclusion

Numbers are trickier than we usually think. Not only are there different kinds of numbers, but any given number can be represented in many different ways. Choosing the right kind of number depends on what we want to express by it (i.e., the number’s function or our use of it).

16.5.1 Summary

Key question: Do we mean the number values or their representations?

- If value: What do the number values denote (semantics)? What types of numbers and accuracy level is needed?

- If representations: In which context are number representations needed? (As numerals or words? Which system? Which accuracy?)

16.5.2 Resources

16.5.2.2 Factors

Resources for using factors in base R:

McNamara, A., & Horton, N. J. (2018). Wrangling categorical data in R. The American Statistician, 72(1), 97–104. doi: 10.1080/00031305.2017.1356375

Also available at PeerJ.com: https://doi.org/10.7287/peerj.preprints.3163v2Son Nguyen (2020). Efficient R programming. See Section 3.4 Factors.

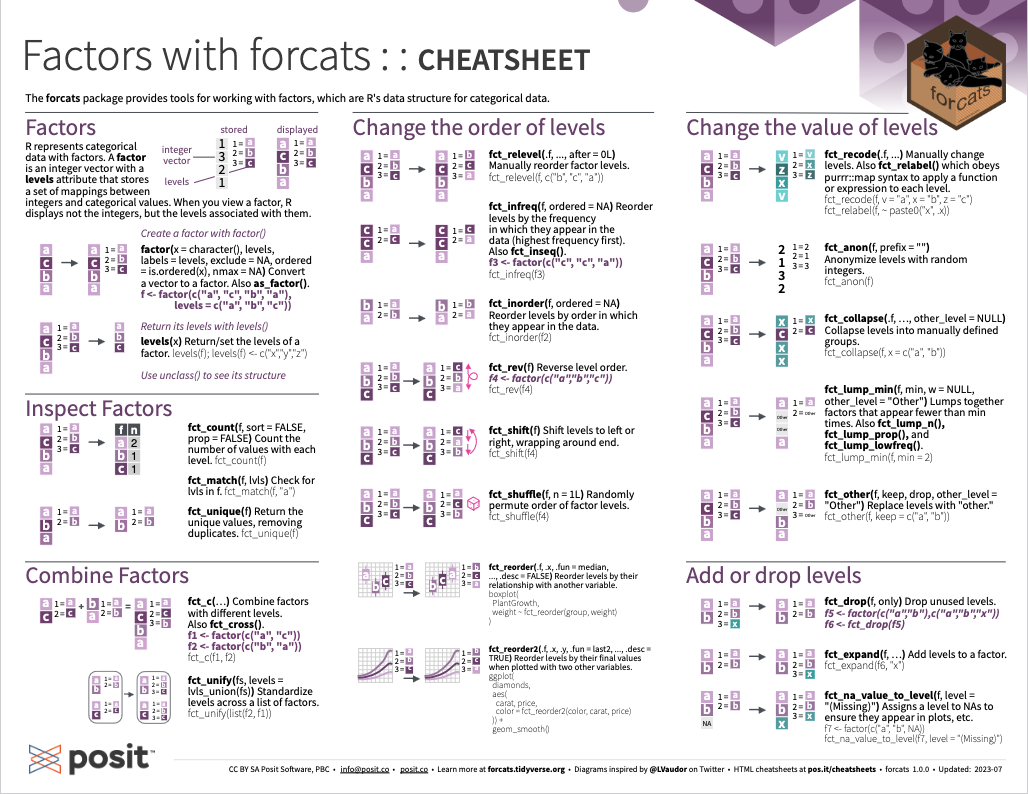

Handling factors in tidyverse contexts using the forcats package (Wickham, 2025a):

Chapter 15 Factors of Wickham & Grolemund (2017)

Chapter 16 Factors of Wickham, Çetinkaya-Rundel, et al. (2023)

A good overview of forcats is found on one of the Posit cheatsheets:

Figure 16.1: Handling factors with forcats from Posit cheatsheets.

16.6 Exercises

16.6.1 Converting decimal numbers into base N

- Create a conversion function

dec2base(x, base)that converts a decimal numberxinto a positional number of different base (with \(2 \leq\)base\(\leq 10\)). Thus, thedec2base()function provides a complement tobase2dec()from the ds4psy package:

- Use your

dec2base()function to compute the following conversions:

dec2base(100, base = 2)

dec2base(100, base = 3)

dec2base(100, base = 5)

dec2base(100, base = 9)

dec2base(100, base = 10)- Create a brief simulation that samples \(N = 20\) random decimal numbers \(x_i\) and

basevalues \(b_i\) \((2 \leq b_i <= 10)\) and shows that

base2dec(dec2base(\(x_i,\ b_i\)),\(b_i\)) ==\(x_i\)

(i.e., converting a numeric value from decimal notation into a number in base \(b_i\) notation, and back into decimal notation yields the original numeric value).

Solution

| n_org | base | n_base | n_dec | same |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6014 | 7 | 23351 | 6014 | TRUE |

| 364 | 8 | 554 | 364 | TRUE |

| 8030 | 3 | 102000102 | 8030 | TRUE |

| 8756 | 4 | 2020310 | 8756 | TRUE |

| 5858 | 7 | 23036 | 5858 | TRUE |

| 5170 | 8 | 12062 | 5170 | TRUE |

| 461 | 6 | 2045 | 461 | TRUE |

| 518 | 10 | 518 | 518 | TRUE |

| 9642 | 6 | 112350 | 9642 | TRUE |

| 7861 | 9 | 11704 | 7861 | TRUE |

| 4785 | 10 | 4785 | 4785 | TRUE |

| 5514 | 5 | 134024 | 5514 | TRUE |

| 4943 | 8 | 11517 | 4943 | TRUE |

| 2666 | 4 | 221222 | 2666 | TRUE |

| 305 | 9 | 368 | 305 | TRUE |

| 7750 | 3 | 101122001 | 7750 | TRUE |

| 5471 | 5 | 133341 | 5471 | TRUE |

| 5043 | 7 | 20463 | 5043 | TRUE |

| 2206 | 7 | 6301 | 2206 | TRUE |

| 3280 | 4 | 303100 | 3280 | TRUE |