N = 100 # number of spaces on board

s = N + 1 # number of states

k = 6 # number of sides on die

# P0 is the transition matrix if there were no chutes/ladders

P0 = matrix(rep(0, s * s), nrow = s)

for (i in 1:(N - 1)){

for (j in min(i + 1, N):min(i + k, N)){

if (j == N){

P0[i, j] = (i - N + k + 1) / k

# don't need to land on 100 exactly

} else {

P0[i, j] = 1 / k

}

}

}

P0[N, N] = 1 # absorbing state

P0[s, 1:k] = 1 / k # initial stateChutes and Ladders and MCMC

Disclaimer: I wrote the code for this application a long time ago and haven’t updated it. It could be much improved, especially with respect to the plots. You’re welcome to use the code as is, but suggestions/improvements would be greatly appreciated!

This investigation concerns the boardgame Chutes and Ladders. Detailed instructions and some code has been provided; please be sure to read carefully.

The board has 100 spaces, labeled 1, 2, …, 100. A player starts off the board. A player generally moves on the board according to the roll of a fair six-sided die. For example, if the player is currently on space 13 and they roll a 5, then they move to space 18. However, the board also has 9 ladders which help the player climb the board.

- Ladder from space 1 to space 38 (that is, landing on space 1 immediately moves the player to space 38, a gain of +37 spaces)

- From 4 to 14 (+10)

- From 9 to 31 (+22)

- From 21 to 42 (+21)

- From 28 to 84 (+56)

- From 36 to 44 (+8)

- From 51 to 67 (+16)

- From 71 to 91 (+20)

- From 80 to 100 (+20)

There are also 10 chutes (slides) which knock the player back down.

- Chute from 16 to 6 (that is, landing on space 16 immediately moves the player to space 6, a loss of -10 spaces)

- From 48 to 26 (-22)

- From 49 to 11 (-38)

- From 56 to 53 (-3)

- From 62 to 19 (-43)

- From 64 to 60 (-4)

- From 87 to 24 (-63)

- From 93 to 73 (-20)

- From 95 to 75 (-20)

- From 98 to 78 (-20)

The game ends when the player makes it to space 100. (We’ll assume only one player.) We are interested in \(T\), the number of moves (rolls) needed until spot 100 is reached (the player doesn’t need to land on 100 exactly). The position of the player after the nth move can be modeled as a Markov chain with transition matrix Pgame defined in the code below.

Technical note: you start off the board, so while there are 100 spaces on the board, there are 101 states for the MC. To make the indices of the matrix correspond to the actual spaces on the board, I’m going to call “off the board” state 101. This way P[1,3] will refer to the probability of moving from space 1 to space 3 (which would not be true if we called “off the board” state 0). So \(T\) is the RV counting how many moves it takes to get from state 101 (off the board) to state 100. (The plot in the make_board below function rearranges so off the board is state 0 — because it looked weird otherwise — but this is just for plotting.)

# The make_board function takes as an input the starting spaces

# for chutes and ladders and outputs the transition matrix

# add the chutes/ladders by swapping appropriate columns

# with an annoying little detail for the two short chutes

# e.g. you can get from 50 to 53 by rolling a 3

# or by rolling a 6 and then sliding down the chute from 56 to 53

make_board <- function(ladder_start, chute_start, plot = FALSE){

ladder_length = c(8, 10, 16, 20, 20, 21, 22, 37, 56)

ladder_end = ladder_start + ladder_length

chute_length = c(3, 4, 10, 20, 20, 20, 22, 38, 43, 63)

chute_end = chute_start - chute_length

P = P0

for (j in 1:length(ladder_start)){

i = which(P[, ladder_start[j]] > 0)

P[i, ladder_end[j]] = P[i, ladder_start[j]]

P[i, ladder_start[j]] = 0

P[ladder_start[j], ] = rep(0, s)

P[ladder_start[j], ladder_end[j]]=1

}

for (j in 1:length(chute_start)){

i = which(P[, chute_start[j]] > 0)

i1 = i[which(i <= chute_end[j])]

P[i1, chute_end[j]] = P[i1, chute_start[j]] +

P0[i1, chute_end[j]]

P[i1, chute_start[j]] = 0

i2 = i[which(i > chute_end[j])]

P[i2, chute_end[j]] = P[i2, chute_start[j]]

P[i2, chute_start[j]] = 0

P[chute_start[j], ] = rep(0, s)

P[chute_start[j], chute_end[j]] = 1

}

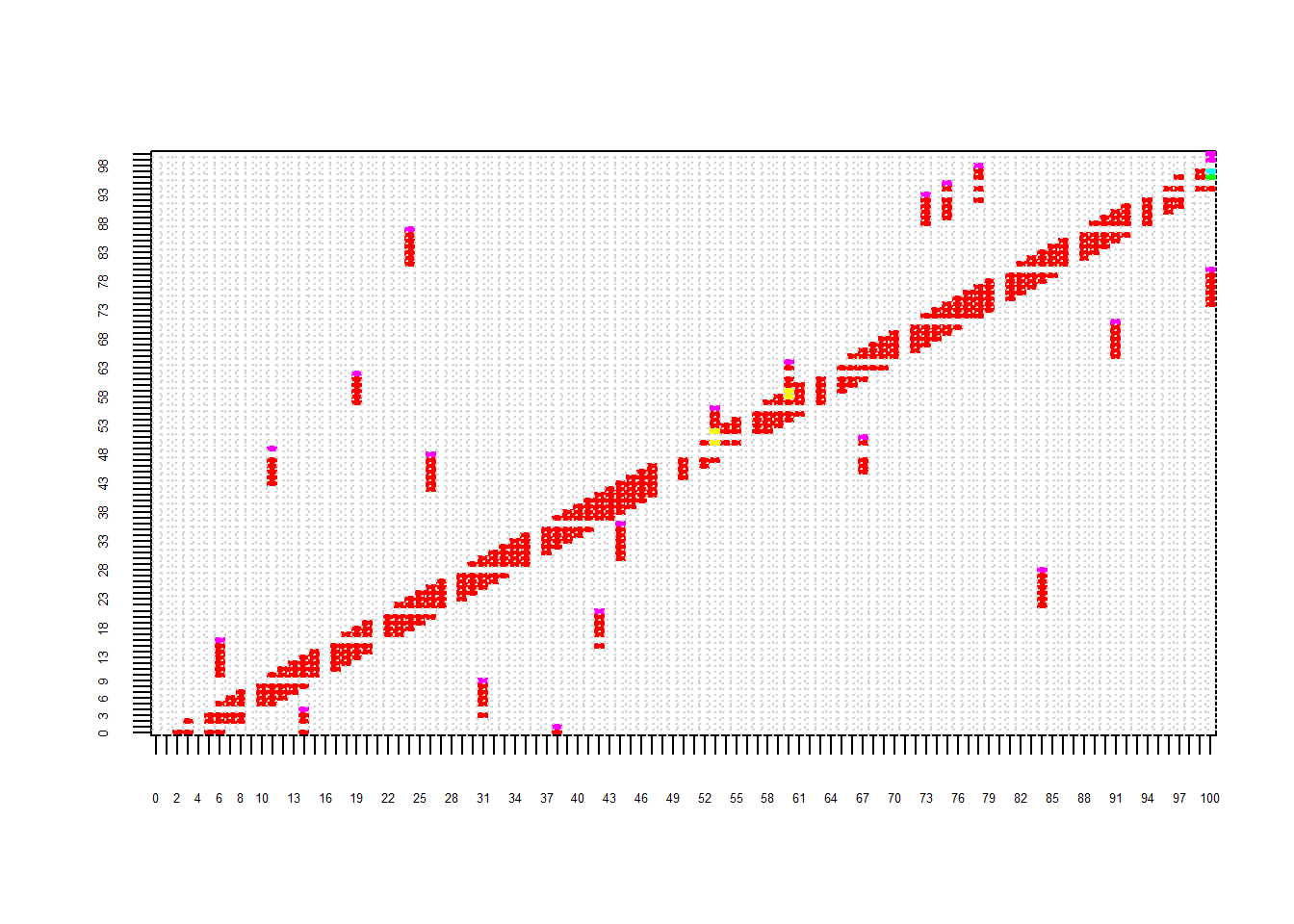

if (plot == TRUE){

image(1:s, 1:s, t(P[c(s, 1:(s - 1)), c(s, 1:(s - 1))]),

xlab = "", ylab = "",

zlim = c(1 / k, 1), xaxt = "n", yaxt = "n",

col = rainbow(k))

axis(1, at = 1:s, labels = 0:(s - 1), cex.axis=0.4)

axis(2, at = 1:s, labels = 0:(s - 1), cex.axis=0.4)

grid(s, s)

}

return(P)

}# generate the transition matrix for the actual game

Pgame = make_board(

ladder_start = c(36, 4, 51, 71, 80, 21, 9, 1, 28),

chute_start = c(56, 64, 16, 93, 95, 98, 48, 49, 62, 87),

plot = TRUE)

# Check that all row sums are 1

which(!rowSums(Pgame) == 1)integer(0)The following assumptions should be apparent from the transition matrix, but to be clear:

- If the player rolls and lands on a chute/ladder, this counts as one move, not two.

- The player does not have to land on 100 exactly. For example, from spot 97, a roll or 3 or higher will win.

Problem 1.

First run the code above to create the Pgame matrix to use.

- Solve for \(E(T)\) without first finding the distribution of \(T\).

- Solve for the exact distribution of \(T\) and plot it. (Technically, \(T\) can take infinitely many values, but feel free to cut off when the probabilities become sufficiently small.) Find \(E(T)\) based on this distribution. Compare the expected value to the previous part.

- Write code to simulate run the chain and simulate the distribution of \(T\). Plot the simulated distribution, use it to estimate the expected value, and compare to the previous part.

Problem 2.

Suppose you were designing a new Chutes and Ladders board. How does the placement of the chutes and ladders on the board affect the expected value of \(T\)? In particular, is there a way to place the chutes/ladders to minimize the expected number of moves? In this problem, you’ll write an MCMC algorithm to find the board which minimizes \(E(T)\).

Assume the number of chutes does not change and the length of each chute does not change; similarly for ladders. What you can change is which square starts the chute/ladder. For example, there is currently a ladder from 4 to 14; you could change this into a ladder from 50 to 60. To be clear, your board should have

- 9 ladders with lengths 8, 10, 16, 20, 20, 21, 22, 37, 56

- 10 chutes with length 3, 4, 10, 20, 20, 20, 22, 38, 43, 63

You can use the make_board function I have written above to create a transition matrix corresponding to a revised board. There are three inputs: one vector of length 9 with the starting spaces (bottoms) of the ladders, one vector of length 10 with the starting spaces (tops) of the chutes, and the last input is just TRUE/FALSE for whether or not you want to plot a visual of the transition matrix like the one above. Notice how I used the function to generate the transition matrix Pgame for the actual board. Enter the starting spaces in order of length from smallest to largest (so the first element of your ladder vector will be for the starting space for the ladder of length 8, the last element for length 56.)

Some rules to follow:

- You can only define chutes/ladders that start and end on the board.

- I haven’t included any error checks in the function, so it will be up to you to make sure you enter valid starting spaces (i.e, that your chutes/ladders don’t go off the board).

- You should not design a board with a chute that ends at the start of another chute or a ladder that ends at the start of another ladder. This would give you a way of effectively lengthening ladders or chutes, which voliates the spirit of this exercise.

- Similarly, you should not have chutes that end at the start of ladders and vice versa (as a way of creating shorter chutes).

- I would appreciate it if you wouldn’t have multiple ladders than end on the same space, or multiple chutes that end on the same space, unless you want to revise the

make_boardcode to accommodate this. While technically this would be allowed, it is annoying to code. It’s a good idea to check that the row sums of any transition matrix are 1. If you do see sums that are less than 1, it’s probably because multiple ladders (or chutes) are ending in the same spot. (If you notice other problems when using themake_boardfunction, let me know asap.)

Technical note: After creating a new transition matrix, you could delete the states corresponding to the starting spaces of the chutes and ladders, because it’s not possible to land on those spaces without moving directly to another, so you could never start a turn in one of those spaces. I left the starting spaces in, just so the indexing would be simpler, e.g. P[10,15] always refers to the probability of moving from space 10 to space 15.

What to do. First, think about what the optimal placement might look like. Then, write an MCMC algorithm to find the board that minimizes \(E(T)\). Your MCMC algorithm should involve:

- Proposing a new state, that is, proposing a new board. A board is identified by the starting spaces of the chutes and the starting spaces of the ladders (that is, the inputs to the

make_boardfunction). - Finding the expected value of \(T\) for the proposed board and then deciding whether or not to accept the proposed board. Note: if the proposed board is not valid (e.g., chutes/ladders land off the board), then it should be rejected.

Run the algorithm until you think it has converged and you have found the optimal board. Identify the the starting spaces for the chutes and ladders for this board. Then repeat Problem 1 for your optimal board, and compare the distribution of \(T\) for your board to the one from the actual game. Write a few sentences summarizing your results.