Chapter 20 Analyzing proportions

Motivating scenarios: We want to estimate probabilities portions from yes/no outcomes, describe uncertainty in this estimate, and test the null hypothesis that observed proportions come from a population with a specified probability.

Learning goals: By the end of this chapter you should be able to

- Explain probabilities and proportions.

- Which is the parameter? Which is the estimate?

- Explain the binomial distribution – when would you use it?

- Understand the binomial distribution and connect it to simple probability rules.

- Quantify the expected mean and variability of a binomial distribution.

- Be able to appropriately conduct and interpret a binomial test with both math and the

binom.test()function in R.

- Simulate with

rbinom()and calculate / analyze probabilities withdbinom(),pbinom(), andqbinom()).

20.1 Probabilities and proportions

As discussed in Chapter 14, the proportion of each outcome is the number of times we see that outcome divided by the number of times we seen any outcome. A probability describes a parameter for a population (i.e. the proportion of a given outcome in a sample of infinite size). So, the proportion describes an estimate of the probability from a sample.

20.2 Estimating parameters and testing if they deviate from a mathematical distribution

In Chapters 17, 18, and 19 we considered estimating associations between variables and testing the null hypothesis of “no association” by permutation. But there are some statistical problems for which we can’t (or don’t) permute to generate our null distribution.

Say we are interested to know if a certain gene selfishly distorts meiosis in its favor to over-transmit itself to the next generation. Our null hypothesis here would be that meiosis is fair – that is that heterozygous parents are equally likely to transmit alternative alleles to their offspring, and the alternative hypothesis is that heterozygous parents are not equally likely to transmit alternative alleles to their offspring.

How can we test such hypotheses? Well we can use well-characterized mathematical sampling distributions – in this case we can make use of the binomial distribution, which describes the probability of \(k\) successes out of n random trials, each with a probability of success, \(p\). This is my favorite mathematical distribution because

- I can fully derive it and understand the math.

- It is super useful and common.

In the next chapters we’ll move away from the discrete binomial distribution and into the normal and t-distributions,

20.3 Deriving the Binomial distribution.

20.3.1 Example: Hardy-Weinberg-Equilibrium

You have likely come across Hardy Weinberg as a way to go from allele to genotype frequencies. This is a binomial sample of size two (because diploids), where the probability of successes, p, is the allele frequency. As a quick refresher, in a diploid population with some biallelic locus with allele \(A\) in frequency \(p\) we expect the following genotype frequencies

- \(f_{AA}= p^2\)

- \(f_\text{heterozygote} = 2p(1-p)\)

- \(f_{aa} = (1-p)^2\)

If you remember the assumptions of Hardy Weinberg, they basically say we are sampling

- Without bias (no selection)

- Independently (random mating)

- From the population we think we’re describing (no migration)

The additional assumptions of limited sampling error (no genetic drift), and no mutation are silly and we’ll ignore them today.

Where does the Hardy-Weinberg Equation come from? Well from our basic probability rules —

- \(f_{AA}= p \times p\).

- Get \(A\) from a random mom with probability \(p\), AND \(A\) from a random dad with probability \(p\).

- p(child allele A & A) = p(A from mom) x p(A from dad).

- Get \(A\) from a random mom with probability \(p\), AND \(A\) from a random dad with probability \(p\).

- \(f_{Aa}+ f_{aA}= p(1-p) + (1-p)p\).

- Get \(A\) from a random mom with probability \(p\), AND \(a\) from a random dad with probability \(1 - p\). OR Get \(a\) from a random dad with probability \(1- p\), AND \(A\) from a random mom with probability \(p\).

- p(child allele A & allele a) = [p(A from mom) x p(a from dad)] + [p(a from mom) x p(A from dad)].

- Get \(A\) from a random mom with probability \(p\), AND \(a\) from a random dad with probability \(1 - p\). OR Get \(a\) from a random dad with probability \(1- p\), AND \(A\) from a random mom with probability \(p\).

- \(f_{aa} = (1-p)^2\)

- Get \(a\) from a random mom with probability \(1 - p\), AND \(a\) from a random dad with probability \(1 - p\).

- p(child allele a & a) = p(a from mom) x p(a from dad).

- Get \(a\) from a random mom with probability \(1 - p\), AND \(a\) from a random dad with probability \(1 - p\).

20.3.2 General case of binomial sampling

Looking at this we can see this logic – the probability of having \(k\) successes – in this case \(k\) copies of allele \(A\) out of \(n\) trials – in this case, two because we’re dealing with diploids – equals \(\text{# of ways to get k successes} \times p^k\times(1-p)^{n-k}\).

We multiply by the \(\text{# of ways to get k successes}\) because we are adding up all the different ways to get \(k\) successes out of \(n\) trials. In mathematical notation, the number of ways to get \(k\) successes out of n trials is \({n \choose k}\), and equals \(\frac{n!}{k!(n-k)!}\), where the \(!\) means factorial. As a quick refresher on factorials, \(n!=\prod_{i=1}^{n}i\) is \(n \geq 1\), and 1 if \(n=1\). So

\(0! = 1\)

\(1! = 1\)

\(2! = 2\times 1 = 2\)

\(3! = 3 \times 2\times 1 = 6\)

\(4! = 4 \times 3 \times 2\times 1 = 24\) etc…

If we don’t want to do math, R can do it for us – for example factorial(4) returns 24.

In our Hardy Weinberg example,

- There is only one way to be homozygous for \(A\)

- you need to get \(A\) from both mom AND dad.

- \({2 \choose 0} = \frac{2!}{0!(2-0)!} = \frac{2 \times 1}{1 \times 2 \times 1}=1\)

- you need to get \(A\) from both mom AND dad.

- There are two ways to be heterozygous –

- you can get \(A\) from mom and \(a\) from dad OR \(A\) from dad and \(a\) from mom.

- \({2 \choose 1} = \frac{2!}{1!(2-1)!} = \frac{2 \times 1}{1 \times \times 1}=2\)

- There is only one way to be homozygous for \(a\)

- you need to get \(a\) from both mom AND dad.

- \({2 \choose 2} = \frac{2!}{2!(2-2)!} = \frac{2 \times 1}{2 \times 1 \times 1}=1\)

- you need to get \(a\) from both mom AND dad.

20.4 The binomial equation

So we can write out the binomial equation as

\[\begin{equation} \begin{split}P(X=k) &={n \choose k} \times p^k\times(1-p)^{n-k}\\ &= \frac{n!}{(n-k)!k!}\times p^k\times(1-p)^{n-k} \end{split} \tag{20.1} \end{equation}\]

Remember, \({n \choose k}\) (aka the binomial cofficient) captures the number of ways we can get a give outcome (e.g. the two ways to be heterozygous), and \(p^k\times(1-p)^{n-k}\) is the probability of any one way of getting that outcome.

20.4.1 The binomial equation in R

20.4.1.1 Math

R has a bunch of sampling distributions in its head. We can have R find the probability of getting some value from the binomial distribution with the dbinom() function, which takes the arguments,

x– the number of successes – i.e. \(k\) in our equation.

prob– the probability of success – i.e. \(p\) in our equation.

size– the number of trials – i.e. \(n\) in our equation.

So, we can find the probability of being heterozygous at a locus (i.e. x = k = 1), in a diploid (i.e. size = n = 2) for an allele at frequency 0.2 (i.e. prob = p = 0.2) as dbinom(x = 1, prob = 0.2, size = 2) = 0.32. This value matches the math – \({2 \choose 1}0.2^1\times(1-0.2)^{2-1} = 2 \times 0.2 \times 0.2 = 0.32\).

x can be a vector, so for example, the frequency of each diploid genotype in a randomly mating population with allele A at frequency 0.2 is:

tibble(genos = c("aa","Aa","aa"),

freqs = dbinom(x = 0:2, size = 2, prob = .2))## [38;5;246m# A tibble: 3 x 2[39m

## genos freqs

## [3m[38;5;246m<chr>[39m[23m [3m[38;5;246m<dbl>[39m[23m

## [38;5;250m1[39m aa 0.64

## [38;5;250m2[39m Aa 0.32

## [38;5;250m3[39m aa 0.04So dbinom(x = 0:sample_size, size = sample_size, prob = p_null) generates the sampling distribution for the probability of x successes in a sample of size sample_size under some hypothesized probability of success, p_null.

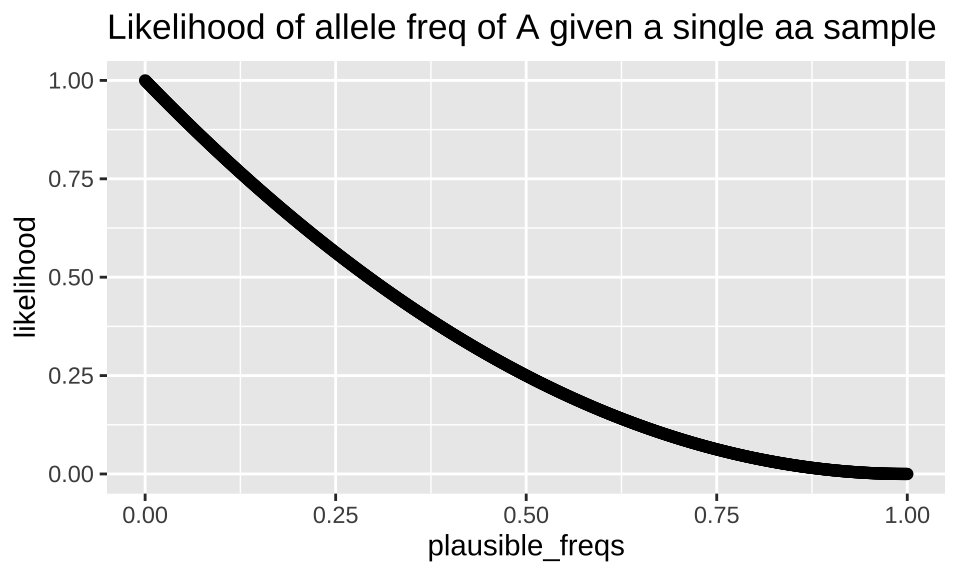

Similarly prob can be a vector. This can be useful for calculating likelihoods. Recall, that we compute a likelihood exactly like a conditional probability, but when we do so, we vary the parameter while keeping the outcome (our observations) constant. So, for example, we can calculate the likelihood of a bunch of plausible population allele frequencies if we sequence a single individual who turns out to be homozygous for \(a\) \(P(\text{allele freq = p | aa})\) as follows:

tibble(plausible_freqs = seq(0,1,.001),

likelihood = dbinom(x = 0, size = 2, prob = plausible_freqs )) %>%

ggplot(aes(x = plausible_freqs, y = likelihood)) +

geom_point()+

labs(title = "Likelihood of allele freq of A given a single aa sample")

20.4.2 Simulating from a binomial

We can use these probabilities to generate random draws from a binomial distribution in with the rbinom() function, which takes the arguments,

n– the number of replicates.

prob– the probability of success – i.e. \(p\) in our equation.

size– the number of trials – i.e. \(n\) in our equation. I always getsizeandnconfused, and have to double check.

So we can generate a single diploid genotype from a population with allele \(A\) at frequency 0.02 as

rbinom(n = 1, prob = 0.2, size = 2)## [1] 0We can similarly generate a sample of 1000 diploids from a population with allele \(a\) at frequency 0.2 and store it in a tibble as follows

num_inds <- 10000

tibble(individual = 1:num_inds,

num_A_alleles = rbinom(n = num_inds, prob = 0.2, size = 2))20.5 Quantifying Variability in a Binomial sample

You may think that proportion data have one data point — the proportion. This is wrong, rather, proportion data have as many data points as the sample size. So we can calcualte a variance as we did before. For example a population variance, \(\sigma^2 = \frac{\sum{(x_i - \overline{x})^2}}{n}\). Here, \(x\) is 0 or 1. So if our proportion is \(p=\overline{x}\) we can simplify the variance as

\[\begin{equation} \begin{split}\sigma^2 &= \frac{1}{n}(\sum{(x_i - p)^2})\\ &= \frac{1}{n} (n \times p(1-p)^2 + n \times (1-p) \times (0-p)^2)\\ &= \frac{1}{n} (n \times p \times (1-p)^2+n \times p^2\times(1-p))\\ &= \times p \times(1-p) \times ((1-p)+p)\\ &= p \times (1-p) \times (1)\\ &= p \times (1-p) \end{split} \tag{20.2} \end{equation}\]

Likewise, the sample variance equals \(s^2 = \frac{n\times p\times(1-\widehat{p})}{n-1}\), where the hat over p, \(\widehat{p}\), reminds us that this is an estimate. We find the standard deviation as the square root of the variance, as always.

20.6 Uncertainty in our estimate of the propotion

This can be hard with a binomial distribution especially when the sample size is small and/or values are near zero or one. To consider this challenge, imagine we get five successes of five tries. The variance would be zero, the standard error undefined etc… Ugh 😞.

Still, we can try to estimate the standard error as the sample standard deviation divided by the square root of the sample size. Because this distribution is discrete and bounded, its just hard to come up with an exactly correct estimate for the confidence interval, and there are therefore numerous, slightly different and often tedious equations for doing so wikipedia. For now know that R uses the one in Clopper and Pearson (1934), and that they are all good enough.

, which sparks no joy, and just serves to allow for a math question on a test.](https://miro.medium.com/max/1960/1*wUCVwT-wFIs_Z1_WbtwC0Q.png)

Figure 20.1: So excited to not teach the AgrestiCoull Interval, which sparks no joy, and just serves to allow for a math question on a test.

20.7 Testing the null hypothesis of a \(p\) = \(p_0\)

We can use the binomial sampling distribution to test the null hypothesis that a sample came from a population with a given null of success, \(p_0\). For example, say we were curious to test the null hypothesis that a single individual with an AA genotype (i.e. two successes) is from a population with an allele frequency of 0.2.

- \(H_0\): The individual is from a population with allele \(A\) at frequency

0.2.

- \(H_A\): The individual is not from a population with allele \(A\) at frequency

0.2.

For now well pretend this is a one tailed test (in reality this is a two tailed test, but there is no area on the other tail because a homozygote for \(a\) is so likely, so the answer is the same either way you slice it).

So the probability that we would see two \(A\) alleles in a sample of two from a population with the \(A\) allele at frequency 0.2 is Binomially distributed with p = 0.2 and n =2, aka \(P(K=2) \sim B(p=0.2,n =2) = {2 \choose 2}.2^2\times(.8)^{0}=.04\). Or in R dbinom(x=2, p=.2, size =2) = 0.04. In this case there is no way to be more extreme so this is our p-value.

Remember this DOES NOT mean this individual did not came from a population (call it pop1) with allele \(A\) at frequency 0.2. NOR does it mean that the individual has a 0.04 probability of belonging to such a population. The answer to that questions is a Bayesian statement.

20.7.1 Testing the null hypothesis of a \(p\) = \(p_0\) in R

We can use R to calculate p-values for a sample from the binomial. We can think of doing this in three different ways, ranked from us being largely in control to letting R do everything.

- Summing probabilities with

dbinom()As we did above we can usedbinom()and sum up all the ways to be as or more extreme. For a one tailed test this would besum(dbinom(x = 0:x_observed, size = sample_size, prob = p_null)), if our observation was less than the null prediction, andsum(dbinom(x = x_observed:sample_size, size = sample_size, prob = p_null))if our observation exceeded the null prediction. We simply combine these for a two tailed test by adding up both tails that are as or more distant from the null as follows Note in our genetic example we only considered one tail because the other tail only included impossible counts like-2.

null_prob <- 1/3 # say we, for some reason, had a null probability of success of 1/3 (say you played a game with 3 three contestants)

obs <- 7 # say we had 7 "successes" (say you won seven games)

sample_size <- 12 # say you had 12 observations, like you played 12 games

prediction <- sample_size * null_prob

tibble(x = 0:sample_size,

p_obs = dbinom(x = x, size = sample_size, prob = null_prob),

as_or_more_extreme = abs(x - prediction) >= abs(prediction - obs)) %>%

filter(as_or_more_extreme) %>%

summarise(p_val = sum(p_obs))## [38;5;246m# A tibble: 1 x 1[39m

## p_val

## [3m[38;5;246m<dbl>[39m[23m

## [38;5;250m1[39m 0.120- Having

pbinom()sum probabilities for us Rather than writing out all the options and summing,pbinom()can add this up for us. For a one tailed test this would bepbinom(q = x_observed, size = sample_size, prob = p_null), if our observation was less than the null prediction, andpbinom(q = x_observed - 1, size = sample_size, prob = p_null, lower.tail = FALSE)if our observation exceeded the null prediction. We simply combine these for a two tailed test by adding up both tails that are as or more distant from the null as follows. Note in our genetic example we only considered one tail because the other tail only included impossible counts like-2.

tibble(tail = c("lower","upper"),

x = c(prediction - abs(prediction - obs), prediction + abs(prediction - obs)),

p_as_or_more = case_when(tail == "lower" ~ pbinom(q = x, size = sample_size, prob = null_prob, lower.tail = TRUE),

tail == "upper" ~ pbinom(q = x - 1, size = sample_size, prob = null_prob, lower.tail = FALSE)))%>%

summarise(p_val = sum(p_as_or_more))## [38;5;246m# A tibble: 1 x 1[39m

## p_val

## [3m[38;5;246m<dbl>[39m[23m

## [38;5;250m1[39m 0.120- Having

binom.test()do everything for us Rather than doing anything ourselves, we can have thebinom.test()function do everything for us. For the example, above:

binom.test(x = obs, n = sample_size, p = null_prob)##

## Exact binomial test

##

## data: obs and sample_size

## number of successes = 7, number of trials = 12, p-value = 0.1204

## alternative hypothesis: true probability of success is not equal to 0.3333333

## 95 percent confidence interval:

## 0.2766697 0.8483478

## sample estimates:

## probability of success

## 0.5833333As we did in previous chapters, we can tidy this output with the tidy() function in the broom package

library(broom)

binom.test(x = obs, n = sample_size, p = null_prob) %>%

tidy()## [38;5;246m# A tibble: 1 x 8[39m

## estimate statistic p.value parameter conf.low conf.high method alternative

## [3m[38;5;246m<dbl>[39m[23m [3m[38;5;246m<dbl>[39m[23m [3m[38;5;246m<dbl>[39m[23m [3m[38;5;246m<dbl>[39m[23m [3m[38;5;246m<dbl>[39m[23m [3m[38;5;246m<dbl>[39m[23m [3m[38;5;246m<chr>[39m[23m [3m[38;5;246m<chr>[39m[23m

## [38;5;250m1[39m 0.583 7 0.120 12 0.277 0.848 Exact binomial test two.sidedI would almost always use the binom.test() function instead of calcualting things myself, because there’s less room for error. I only use the other approaches in special cases where I need custom solutions. So the other bits are mainly for explanation.

20.7.2 Using the binomial sampling distribution for Bayesian Inference

Again the p-values above describe the probability that we would see observations as or more extreme as we did, assuming the null hypothesis is true. We can, of course, use the binomial sampling distribution to make Bayesian statements. Here \[P(Model|Data) = \frac{P(Data|Model) \times P(Model)}{P(Data)}\], where model is a proposed probability of success. We call the quantity \(P(Data|Model)\), the posterior probability, as this is the probability of our model after we have the data. By contrast, the prior probability, \(P(Model)\) is set before we get this data. So remember that the likelihood, \(P(Model|Data)\) is calculated like a conditional probability.

So, returning to our \(AA\) homozygote found in a population (let’s call it pop1) where allele \(A\) is at frequency 0.2, we found a p-value of 0.04, which is not the probability that the sample came from pop1. We can, however, find this probability with Bayes’ theorem.

EXAMPLE ONE. If, for example, there was a nearby population (call it pop2) with allele \(A\) frequency 0.9 at this locus, and about 3% of individuals found near pop1 actually came from pop2, the posterior probability that it arose from pop1 is \(P(pop1|AA) = \frac{P(AA|pop1) \times P(pop1)}{P(AA)} = \frac{.2^2 \times .97}{.2^2 \times .97 + .9^2 \times .03} \approx 0.63\). (The denominator comes from the law of total probability). So it would be more likely than not that this individual came from pop1.

EXAMPLE TWO. Alternatively, if 30% of individuals near pop1 actually arose from pop2 the posterior probability that this \(AA\) homozygote came from pop1, would be \(P(pop1|AA) = \frac{P(AA|pop1) \times P(pop1)}{P(AA)} = \frac{.2^2 \times .70}{.2^2 \times .70 + .9^2 \times .30} \approx 0.10\), meaning it would be somewhat unlikely (but not shocking) for this individual to have arisen in pop1.

20.8 Assumptions of the binomial distribution

The binomial distribution assumes samples are unbiased and independent.

As such, p-values and confidence intervals from binomial tests with biased and/or non-independent data are not valid.

20.9 Example: Does latex breed diversity?

In 1964, Erlich and Raven proposed that plant chemical defenses against attack by herbivores would spur plant diversification. In a test of this idea (Farrell et al. 1991), the number of species in 16 pairs of sister clades whose species differed in their level of chemical protection were counted. In each pair of sister clades, the plants of one clade were defended by a gooey latex or resin that was exuded when the leaf was damaged, whereas the plants of the other clade lacked this defense. In 13 of the 16 pairs, the clade with latex/resin was found to be the more diverse (had more species), whereas in the other three pairs, the sister clade lacking latex/resin was found to be the not more diverse.

20.9.1 Estimate variability and uncertainty

We can find the sample variance as \[s^2=\frac{n}{n-1}\times p \times {1-p} = \frac{16}{15}\times{\frac{13}{16}}\times{\frac{3}{16}} = \frac{16 \times 13 \times 3}{15 \times 16 \times 16} = \frac{13}{80} = 0.1625\].

Alternatively, we could have found this as

tibble(latex_more_diverse = rep(c(1,0), times = c(13,3))) %>%

summarise(var = var(latex_more_diverse))## [38;5;246m# A tibble: 1 x 1[39m

## var

## [3m[38;5;246m<dbl>[39m[23m

## [38;5;250m1[39m 0.162We can turn this into an estimate of the standard error as \(SE = \frac{s}{\sqrt{n}} = \frac{\sqrt{s^2}}{\sqrt{n}} = \frac{\sqrt{0.1625}}{\sqrt{16}} \approx 0.10\). We will wait until R gives us our 95% CI from binom.test() to say more.

20.9.2 Hypothesis Testing

Hypotheses

\(H_0\): Under the null hypothesis, clades with latex/resin and without are equally likely to be more speciose (i.e. \(p = 0.5\)).

\(H_A\): Under the alternative hypothesis, clades with latex/resin and without are not equally likely to be more speciose (i.e. \(p \neq 0.5\)).

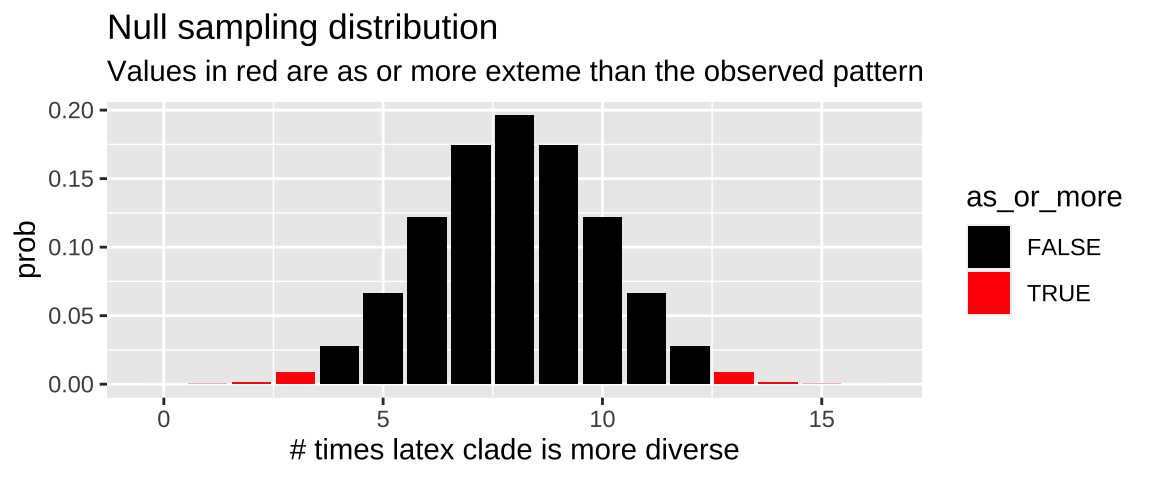

Null sampling distribution

We can use the dbinom() function to make the null sampling distribution

n_trials <- 16

n_success <- 13

null_p <- 0.5

expected <- n_trials * null_p

obs_diff_null <- abs(n_success - expected)

latex_null_dist <- tibble(x = 0:n_trials,

prob = dbinom(x, size = n_trials, p = null_p),

as_or_more = abs(x - expected) >= obs_diff_null)

ggplot(latex_null_dist, aes(x = x, y = prob, fill = as_or_more))+

geom_col()+

scale_fill_manual(values = c("black","red"))+

labs(title = "Null sampling distribution",

subtitle = "Values in red are as or more exteme than the observed pattern",

x = "# times latex clade is more diverse")

Figure 20.2: Binomial sampling distribution for the null hypothesis that there is no association between having gooey latex and diversity. Cases as or more extreme than the 13 of 16 comparisons in the data are filled in red.

Finding a p-value

We find the p-value by summing up the red bars in Figure 20.2.

latex_null_dist %>%

filter(as_or_more) %>%

summarise(p_val = sum(prob)) %>%

pull()## [1] 0.02127075As p = 0.0213, we reject the null hypothesis at the \(\alpha = 0.05\) level and conclude that latex lineages are more speciose.

We can repeat this with the binom.test() function (and get a 05% CI while we’re at it).

binom.test(x = n_success, n = n_trials, p = null_p)##

## Exact binomial test

##

## data: n_success and n_trials

## number of successes = 13, number of trials = 16, p-value = 0.02127

## alternative hypothesis: true probability of success is not equal to 0.5

## 95 percent confidence interval:

## 0.5435435 0.9595263

## sample estimates:

## probability of success

## 0.812520.9.3 Conclusion

In 13 of 16 sister clade comparisons (prop = 0.8125, 95% CI: 0.54 – 0.96) the latex clade was more peciose than other. This is quite unlikely under the null hypothesis (P-value = 0.213), so we reject the null and conclude that latex clades are more speciose. Because this was an observational study, it is unclear if this is caused by the mechanism proposed by Erlich and Raven, that is — that that plant chemical defenses against attack by herbivores would spur plant diversification —or some other cofound (e.g. latex lineages might be preferentially found in speciose regions).

20.10 Testing if data follow a binomial distribution

Say I observe multiple samples and I want to test if they follow a binomial distribution. For example I might have a bunch of diploid genotypes and want to test the null that thy follow Hardy-Weinberg proportions.

Here, the null hypothesis is not that the probability of success is some null value, \(p_0\), but rather, that the data fit a binomial distribution. To test this hypothesis, we

- Estimate \(p\) from the data

- Find the expected proportions of samples with a given number of successes

- Turn this into an expected number

- Calculate a \(\chi^2\) test statistic comparing observed counts of each time we have x-successes to the number (sample size time proportion) expected under the binomial sampling distribution.

- After sensibly combining categories to meet \(\chi^2\) assumptions, we the do a \(\chi^2\) test.

This procedure is known as a \(\chi^2\) goodness of fit test, and is used for many discrete distributions.