15.1 Worked Example

Caren Goldberg and Helene Wagner

1. Overview of Worked Example

a. Goals and Background

Goals: The goal of this worked example is for you to become familiar with creating and analyzing landscape genetic hypotheses using maximum likelihood population effect models (MLPE; Van Strien et al. 2012) and information theory. With this approach, we focus on evaluating evidence for the influence of the (intervening) landscape on link-based metrics (i.e. genetic distance). Incorporating node-based effects (i.e. pond size, etc.) will be covered in the gravity modeling lab.

We will re-analyze a dataset from Goldberg and Waits (2010) using a maximum likelihood population effect model (MLPE).

Here’s a map of the study area. The lines represent those pair-wise links between sampling locations that we will be considering here (graph model: Delaunay triangulation).

b. Data set

In previous labs, you have created genetic distance matrices, so here we are going to start with those data already complete, as are the landscape data. For MLPE, two vectors representing the nodes at the ends of each link must be created. These are already included in the data set (pop1 and pop2).

Each row in the file ‘CSF_network.csv’ represents a link between two pairs of sampling locations. The columns contain the following variables:

- Id: Link ID.

- Name: Link name (combines the two site names).

- logDc.km: Genetic distance per geographic distance, log transformed (response variable).

- LENGTH: Euclidean distance.

- slope: Average slope along the link.

- solarinso: Average solar insolation along the link.

- soils: Dominant soil type along the link (categorical).

- ag: Proportion of agriculture along the link.

- grass: Proportion of grassland along the link.

- shrub: Proportion of shrubland along the link.

- hi: Proportion of high density forest along the link.

- lo: Proportion of low density forest along the link.

- dev: Proportion of development (buildings) along the link.

- forest: Proportion of forest (the sum of hi and lo) along the link.

- pop1: ‘From’ population.

- pop2: ‘To’ population.

d. Import data

First, read in the dataset. It is named CSF (Columbia spotted frog) to differentiate it from the RALU dataset you have used in previous labs (same species, very different landscapes).

CSFdata <- read.csv(system.file("extdata", "CSF_network.csv",

package = "LandGenCourse"))

head(CSFdata) ## Id Name logDc.km LENGTH slope solarinso soils ag

## 1 1 CeGr to FeCr -5.664895 5449.643 11.328851 16332.75 thirteen 0.00000000

## 2 2 CeGr to FlCr -5.786712 8352.643 12.822890 16142.01 one 0.01351351

## 3 43 CeGr to Krum -5.466544 7232.601 15.852762 16208.67 one 0.00000000

## 4 3 FlCr to Krum -5.473660 6196.521 14.156965 15871.14 twelve 0.00000000

## 5 44 Krum to P37 -5.088242 4470.826 15.381000 15883.31 thirteen 0.00000000

## 6 46 CeGr to LaTr -5.997768 8766.482 9.709769 16298.75 one5 0.00000000

## grass shrub hi lo dev forest pop1 pop2

## 1 0.00000000 0.55319149 0.2553191 0.1914894 0.00000000 0.4468085 1 2

## 2 0.01351351 0.10810811 0.6216216 0.2432432 0.00000000 0.8648649 1 3

## 3 0.00000000 0.19696970 0.6212121 0.1818182 0.00000000 0.8030303 4 1

## 4 0.00000000 0.05084746 0.5932203 0.3559322 0.00000000 0.9491525 3 4

## 5 0.05000000 0.00000000 0.3250000 0.6250000 0.00000000 0.9500000 12 4

## 6 0.20000000 0.21333333 0.2666667 0.3066667 0.01333333 0.5733333 5 1The variable solarinso is on a very different scale, which can create problems with model fitting with some methods. To avoid this, we scale it.

Note: we could use the scale function without specifying the arguments ‘center’ or ‘scale’, as both are ‘TRUE’ by default. The argument ‘center=TRUE’ centers the variable by subtracting the mean, the ‘scale=TRUE’ argument rescales the variables to unit variance by dividing each value by the standard deviation. The resulting variable has a mean of zero and a standard deviation and variance of one.

Take a look at the column names and make sure you and R agree on what everything is called, and on the data types (e.g., factor vs. character).

## 'data.frame': 48 obs. of 17 variables:

## $ Id : int 1 2 43 3 44 46 4 6 7 31 ...

## $ Name : chr "CeGr to FeCr" "CeGr to FlCr" "CeGr to Krum" "FlCr to Krum" ...

## $ logDc.km : num -5.66 -5.79 -5.47 -5.47 -5.09 ...

## $ LENGTH : num 5450 8353 7233 6197 4471 ...

## $ slope : num 11.3 12.8 15.9 14.2 15.4 ...

## $ solarinso : num 16333 16142 16209 15871 15883 ...

## $ soils : chr "thirteen" "one" "one" "twelve" ...

## $ ag : num 0 0.0135 0 0 0 ...

## $ grass : num 0 0.0135 0 0 0.05 ...

## $ shrub : num 0.5532 0.1081 0.197 0.0508 0 ...

## $ hi : num 0.255 0.622 0.621 0.593 0.325 ...

## $ lo : num 0.191 0.243 0.182 0.356 0.625 ...

## $ dev : num 0 0 0 0 0 ...

## $ forest : num 0.447 0.865 0.803 0.949 0.95 ...

## $ pop1 : int 1 1 4 3 12 5 2 1 2 4 ...

## $ pop2 : int 2 3 1 4 4 1 5 6 6 7 ...

## $ solarinsoz: num [1:48, 1] 0.796 -0.28 0.096 -1.808 -1.74 ...

## ..- attr(*, "scaled:center")= num 16192

## ..- attr(*, "scaled:scale")= num 177Nameandsoilsare interpreted as factors,Id,pop1andpop2are vectors of integers, and- everything else is a numeric vector, i.e., continuous variable.

The response Y in our MLPE models will be logDc.km, the genetic distance per geographic distance, log transformed to meet normality assumptions. This was used in the paper as a way to include IBD as the base assumption without increasing k. The landscape variables were then also estimated so that they would not necessarily increase with increasing distance between sites (e.g., proportion of forest between sites).

This is a pruned network, where the links are only those neighbors in a Delauney trangulation. <Capture.PNG>

For this exercise, you will test 5 alternative hypotheses. At the end, you will be invited to create your own hypotheses from these variables and test support for them.

2. Fitting candidate models

a. Alternative hypotheses

In information theory, we evaluate evidence for a candidate set of hypotheses that we develop from the literature and theory. Although it is mathematically possible (and often practiced) to fit all possible combinations of input variables, that approach is not consistent with the methodology (see Burnham and Anderson 2002 Chapter 8, the reading for this unit, for more detail). Here, your “a priori”” set of hypotheses (as in the Week 12 Conceptual Exercise) is as follows:

- Full model: solarinso, forest, ag, shrub, dev

- Landcover model: ag, shrub, forest, and dev

- Human footprint model: ag, dev

- Energy conservation model: slope, shrub, dev

- Historical model: soils, slope, solarinso

b. Check for multicollinearity

Before we add predictor variables to a model, we should make sure that these variables do not have issues with multicollinearity, i.e., that they are not highly correlated among themselves. To this end, we calculate variance inflation factors, VIF.

Make a dataframe of just the variables to test (note, you cannot use factors here):

## Variables VIF

## 1 solarinsoz 1.479273

## 2 forest 3.127104

## 3 dev 1.800218

## 4 shrub 1.523341

## 5 ag 2.532198If you get an error that there is no package called ‘usdm’, use install.packages("usdm").

VIF values less than 10, or 3, or 4, depending on who you ask, are considered to not be collinear enough to affect model outcomes. So we are good to go here. What would happen if we added grass to this?

## Variables VIF

## 1 solarinsoz 1.541954

## 2 forest 97.167730

## 3 dev 55.768172

## 4 shrub 11.657666

## 5 ag 68.852254

## 6 grass 45.970721Question 1: Why would adding in the last land cover cause a high amount of collinearity? Consider how these data were calculated.

The variables ‘forest’, ‘dev’, ‘shrub’, ‘ag’ and ‘grass’ together cover almost all land cover types in the study area. Each is measured as percent area, and together, they make up 100% or close to 100% of the land cover types along each link. Thus if we know e.g. that all ‘forest’, ‘dev’, ‘shrub’ and ‘ag’ together cover 80% along a link, then it is a good bet that ‘grass’ will cover the remaining 20%.

With such sets of compositional data, we need to omit one variable to avoid multi-collinearity (where a variable is a linear combination of other variables), even though the pairwise correlations may be low. For example, there the variable ‘grass’ showed relatively low correlations with the other variables:

## [,1]

## solarinsoz 0.10394523

## forest -0.41341968

## dev -0.23617929

## shrub -0.29807027

## ag 0.01060842c. Fit all five models

The R package corMLPE makes it easy to fit an MLPE model to our dataset. We use the function gls from package nlme to fit a “generalized least squares” model to the data.

This is similar to a spatial regression model we’ve seen in Week 7. The main difference is how we define the correlation structure of the errors: instead of using a function of the spatial coordinates, we use a function of the population indicators: correlation=corMLPE(form=~pop1+pop2).

Note: for linear mixed models, see Week 6 videos. For gls models, see Week 7 videos.

mod1 <- nlme::gls(logDc.km ~ solarinsoz + forest + ag + shrub + dev,

correlation=corMLPE::corMLPE(form=~pop1+pop2),

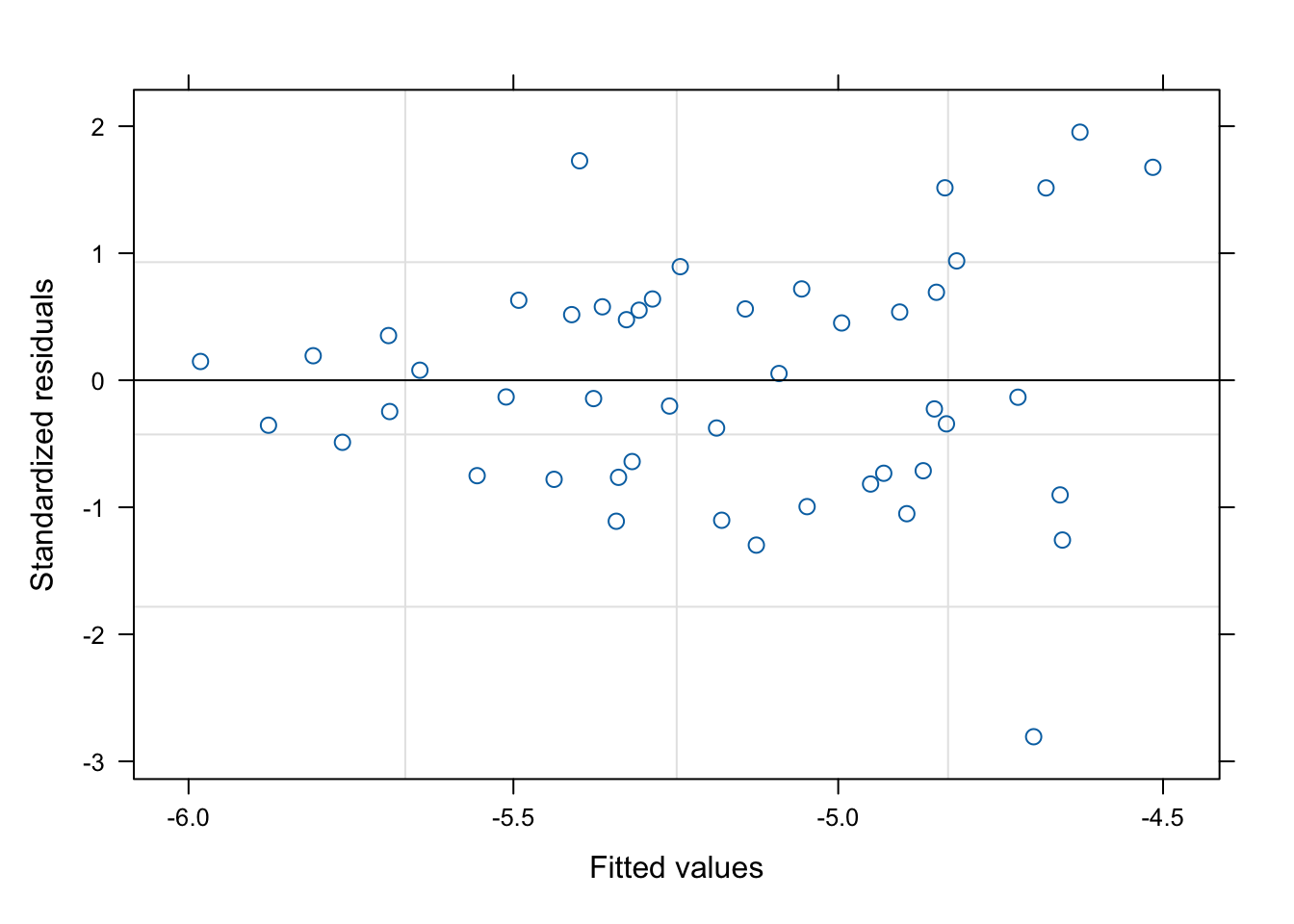

data=CSFdata, method="REML")This is the closest to a full model in our dataset (although our models are not completely nested), so we will take a look at the residuals.

Residuals are centered around zero and do not show large groupings or patterns, although there is some increase in variation at larger numbers (heteroscedasticity: the plot thickens). Here, this means that the model is having a more difficult time predicting larger genetic distances per km. We will keep that in mind as we move on.

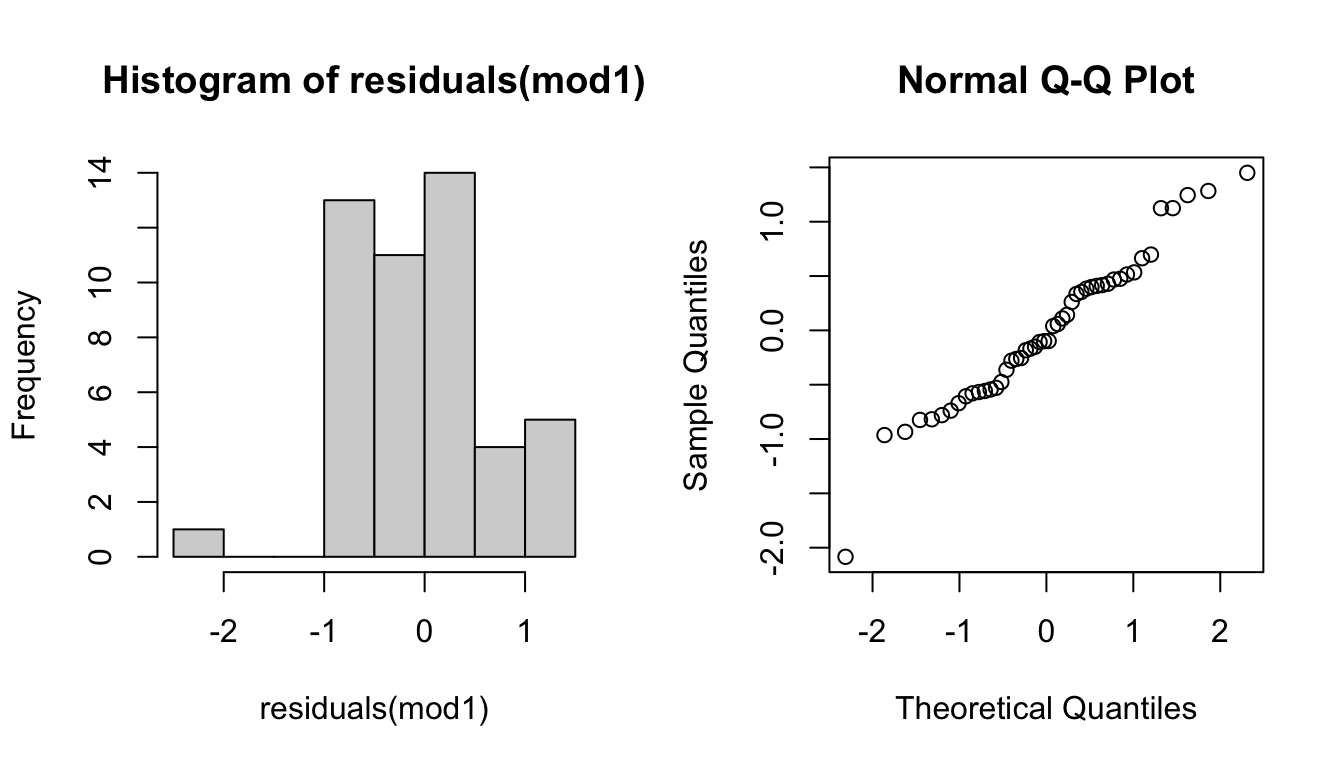

Next we will check to make sure the residuals are normally distributed. This is an important assumption for models fitted with (Restricted) Maximum Likelihood.

We’ll check this with two plots:

- Histogram (left): we want to see a symmetric, bell-shaped distribution.

- Normal probability plot (right): we want to see the points fall on a straight line, without systematic deviations.

These residuals look okay so we will move on (but if this were a publication we would do a closer examination of the shape of the data at the ends of the distribution).

Recall that mod1 had the following formula:

logDc.km ~ solarinsoz + forest + ag + shrub + dev.

Here we’ll use the function update to change the list of predictors in the model (i.e., the right-hand side of the formula, starting with the tilde symbol ~).

d. Compare evidence for models

Our goal here is to compare five models that all have the same random effects (the population effects modeled by the correlation structure) but differ in the fixed effects. Recall from the Week 6 videos:

- Use REML to test random effects, and to get AIC to compare models with different random effects.

- Use ML to test fixed effects, and to get AIC to compare models with different fixed effects.

- Use REML for parameter estimates of fixed effects.

We can use the function update again, this time to change the fitting method from method="REML" to method="ML".

mod1noREML <- update(mod1, method="ML")

mod2noREML <- update(mod2, method="ML")

mod3noREML <- update(mod3, method="ML")

mod4noREML <- update(mod4, method="ML")

mod5noREML <- update(mod5, method="ML")In information theory, we use information criteria (AIC, BIC) to evaluate the relative distance of our hypothesis from truth. For more information, see Burnham and Anderson (2002).

Note: package MuMIn will do this for you, but for this exercise it is useful to see all the pieces of what goes into your evaluation.

Models <- list(Full=mod1noREML, Landcover=mod2noREML, HumanFootprint=mod3noREML,

EnergyConservation=mod4noREML, Historical=mod5noREML)

CSF.IC <- data.frame(AIC = sapply(Models, AIC),

BIC = sapply(Models, BIC))

CSF.IC## AIC BIC

## Full 115.9620 130.9316

## Landcover 113.9757 127.0742

## HumanFootprint 113.4053 122.7613

## EnergyConservation 114.4910 125.7182

## Historical 122.4089 137.3785We now have some results, great!

Now we will work with these a bit. First, because we do not have an infinite number of samples, we will convert AIC to AICc (which adds a small-sample correction to AIC).

First, find the k parameters used in the model and add them to the table.

## AIC BIC k

## Full 115.9620 130.9316 8

## Landcover 113.9757 127.0742 7

## HumanFootprint 113.4053 122.7613 5

## EnergyConservation 114.4910 125.7182 6

## Historical 122.4089 137.3785 8Question 2: How does k relate to the number of parameters in each model?

Disclaimer:

- More research is needed to establish how to best account for sample size in MLPE. Here we use N = number of pairs.

- More generally, more research is needed to establish whether delta values and evidence weights calculated from MLPE are indeed valid.

Calculate AICc and add it to the dataframe (experimental, see disclaimer above):

N = nrow(CSFdata) # Number of unique pairs

CSF.IC$AICc <- CSF.IC$AIC + 2*CSF.IC$k*(CSF.IC$k+1)/(N-CSF.IC$k-1)

CSF.IC## AIC BIC k AICc

## Full 115.9620 130.9316 8 119.6543

## Landcover 113.9757 127.0742 7 116.7757

## HumanFootprint 113.4053 122.7613 5 114.8339

## EnergyConservation 114.4910 125.7182 6 116.5398

## Historical 122.4089 137.3785 8 126.1012e. Calculate evidence weights

Next we calculate evidence weights for each model based on AICc and BIC. If all assumptions are met, these can be interpreted as the probability that the model is the closest to truth in the candidate model set.

Calculate model weights for AICc (experimental, see disclaimer above):

AICcmin <- min(CSF.IC$AICc)

RL <- exp(-0.5*(CSF.IC$AICc - AICcmin))

sumRL <- sum(RL)

CSF.IC$AICcmin <- RL/sumRLCalculate model weights for BIC (experimental, see disclaimer above):

BICmin <- min(CSF.IC$BIC)

RL.B <- exp(-0.5*(CSF.IC$BIC - BICmin))

sumRL.B <- sum(RL.B)

CSF.IC$BICew <- RL.B/sumRL.B

round(CSF.IC,3)## AIC BIC k AICc AICcmin BICew

## Full 115.962 130.932 8 119.654 0.047 0.012

## Landcover 113.976 127.074 7 116.776 0.200 0.085

## HumanFootprint 113.405 122.761 5 114.834 0.527 0.735

## EnergyConservation 114.491 125.718 6 116.540 0.224 0.167

## Historical 122.409 137.378 8 126.101 0.002 0.000Question 3: What did using AICc (rather than AIC) do to inference from these results?

In the multi-model inference approach, we can look across all the models in the dataset and their evidence weights to better understand the system. Here we see that models 1 and 5 have very little evidence of being close to the truth, that models 2 and 4 have more, and that model 3 has the most evidence of being the closest to truth, although how much more evidence there is for model 3 over 2 and 4 depends on which criterion you are looking at. BIC imposes a larger penalty for additional parameters, so it has a larger distinction between these. Let’s review what these models are:

- Full model: solarinso, forest, ag, shrub, dev

- Landcover model: ag, shrub, forest, and dev

- Human footprint model: ag, dev

- Energy conservation model: slope, shrub, dev

- Historical model: soils, slope, solarinso

f. Confidence intervals for predictors

The summary function for the model fitted with “ML” provides a model summary that includes a table with t-tests for each fixed effect in a Frequentist approach (see Week 6 Worked Example). Here we stay within the information-theoretic approach and use a different approach than significance testing to identify the most important predictors.

According to Row et al. (2017), we can use the confidence interval from the variables in the models to identify those that are contributing to landscape resistance. Looking at models 2 and 3, we have some evidence that shrub and forest cover matter, but it’s not as strong as the evidence for ag and development. Let’s look at the parameter estimates to understand more. Note that for parameter estimation we use the REML estimates.

ModelsREML <- list(Full=mod1, Landcover=mod2, HumanFootprint=mod3,

EnergyConservation=mod4, Historical=mod5)Now we’ll estimate the 95% confidence interval for these estimates:

## 2.5 % 97.5 %

## (Intercept) -5.412493 -3.9372220

## forest -1.234534 0.8980824

## ag -2.767849 -0.2789160

## shrub -4.335188 0.4391631

## dev -1.077595 1.4292393## 2.5 % 97.5 %

## (Intercept) -5.3193590 -4.5159303

## ag -2.0215023 -0.1997056

## dev -0.6843463 1.5082812## 2.5 % 97.5 %

## (Intercept) -6.83962997 -5.3057702

## slope 0.02028322 0.1725869

## shrub -3.83624990 1.0650554

## dev 0.22109749 2.6485991In essence, we use the confidence intervals to assess whether we can differentiate the effect of each variable from zero (i.e. statistical significance). The confidence intervals that overlap 0 do not have as much evidence of being important to gene flow, based on simulations in Row et al. (2017). So in this case, there is strong evidence that agriculture influences the rate of gene flow. Note that because the metric is genetic distance, negative values indicate more gene flow.

Question 4: What evidence is there that shrub and forest matter to gene flow from these analyses? What about slope? Would you include them in a conclusion about landscape resistance in this system?

Question 5: What evidence is there that development influences gene flow from these analyses? Would you include it in a conclusion about landscape resistance in this system?

Question 6: We excluded grass from our models because of multicollinearity. How could we investigate the importance of this variable?

3. Your turn to test additional hypotheses!

Create your own (small) set of hypotheses to rank for evidence using the dataset provided. Modify the code above to complete the following steps:

- Define your hypotheses.

- Calculate the VIF table for full model.

- Make a residual plot for full model.

- Create table of AICc and BIC weights.

- Create confidence intervals from models with high evidence weights.

What can you infer from your analysis about what influences gene flow of this species?

4. Nested model (NMLPE) for hierarchical sampling designs

Jaffe et al. (2019) proposed nested MLPE (NMLPE) to account for an additional level of hierarchical sampling. In their example, they had sampled multiple sites (clusters), and within each site, multiple colonies (populations).

When they fitted a MLPE model that did not account for the hierarchical level of sites, there was unaccounted autocorrelation in the residuals. They tested for this by sorting the pairwise distances by site and then calculating an autocorrelation function (ACF) as a function of lag distance along rows (i.e., the lag represented how many rows apart to values were in the dataset). The following pseudo-code is based on code in the supplementary material of Jaffe et al. (2019).

Sort data frame with pairwise data by site, then by pop (pseudo-code). Note: this is only needed for the ACF analysis.

MLPE model (pseudo-code):

# m1 <- gls(Genetic.distance ~ Predictor.distance,

# correlation = corMLPE(form = ~ pop1+pop2), data = df)

## a.f(resid(m1, type='normalized')) ## Autocorrelation functionThe package corMLPE contains another function, corNMLPE2, where we can specify cluster as an additional hierarchical level of non-independence in the data. The ACF of this model did not show any autocorrelation anymore.

NMLPE model (pseudo-code)

# m2 <- gls(Genetic.distance ~ Predictor.distance,

# correlation = corMLPE(form = ~ pop1+pop2, clusters = site), data = df)

## a.f(resid(m2, type='normalized')) ## Autocorrelation functionNote that this is a method to account for hierarchical sampling designs. It does not explicitly account for spatial autocorrelation - indeed, no spatial information is included, unless Euclidean distance is included as a predictor in the model.

5. References

Burnham KP and DR Anderson. 2002. Model Selection and Multimodel Inference: A Practical Information Theoretic Approach. Chapter 8, p. 437-454. Springer-Verlag, New York.

Goldberg CS and LP Waits (2010). Comparative landscape genetics of two pond-breeding amphibian species in a highly modified agricultural landscape. Molecular Ecology 19: 3650-3663.

Jaffé, R, Veiga, JC, Pope, NS, et al. (2019). Landscape genomics to the rescue of a tropical bee threatened by habitat loss and climate change. Evol Appl. 12: 1164– 1177. https://doi-org.myaccess.library.utoronto.ca/10.1111/eva.12794

Row JR, ST Knick, SJ Oyler-McCance, SC Lougheed and BC Fedy (2017). Developing approaches for linear mixed modeling in landscape genetics through landscape-directed dispersal simulations. Ecology & Evolution 7: 3751–3761.

Van Strien MJ, D Keller and R Holderegger (2012). A new analytical approach to landscape genetic modelling: least‐cost transect analysis and linear mixed models. Molecular Ecology 21: 4010-4023.