Chapter 10 The Eurozone and monetary union

By the end of this chapter you should understand:

The history and theories that are used for Common Currency Areas (CCA)

Common and idiosyncratic shocks in the CCA

The real exchange rate and real interest rate channels

The role of fiscal policy and wage coordination in the CCA

10.1 History of the Eurozone

The EMU is a special case of a fixed exchange rate. Analysis of the EMU can allow deeper understanding of fixed exchange rates and the special case where countries do not have control of their monetary policy. An extreme example of this is the difference between the borrowing costs that were experienced by Spain and the UK in the wake of the GFC. Though there are clearly major political reasons to create the Euro, the fundamental economic rationale at that time was a combination of German desire to prevent countries like Italy gaining competitive advantage and for southern EU members to gain some of the German inflation-fighting credibility. The broader economic issues can also be assessed within the framework of the optimum-currency area (OCA) literature. This will be used to evaluate the costs and benefits of having a single currency.

Outline of the costs and benefits is usually attributed to (Mundell 1961). The microeconomic benefits of a monetary union are larger the greater the economic cooperation between regions: elimination of exchange rate risk is said to stimulate investment and trade, increasing efficiency by driving resource to the optimal use; there are lower exchange rate transaction costs; competition should increase with more transparent price comparison; the liquidity of financial markets should increase. A meta-analysis of 34 studies suggests that currency unions boost trade by between 30% and 90% - (Rose and Stanley 2005). The major macroeconomic cost of a monetary union is the loss of independent monetary policy and the ability of the nominal exchange rate to adjust to idiosyncratic economic shocks. These costs will be lower the greater the level of integration and the greater the synchronisation of the business cycle so that common central bank policy is more appropriate. There are a number of factors that influence the degree of integration: the degree of wage and price flexibility that can be a substitute for nominal exchange rate flexibility; the mobility of the labour market (in this case it appears that language and cultural factors reduce EU mobility compared to the US); the size of the fiscal transfers between regions (again the US Federal tax system is a contrast to the relatively low level of transfers in the EU). There are a number of macroeconomic benefits of joining the single currency: a reduction in exchange rate volatility and exchange rate speculation; monetary credibility (if that does not exist); removal of the uncertainty created by the devaluation threat.

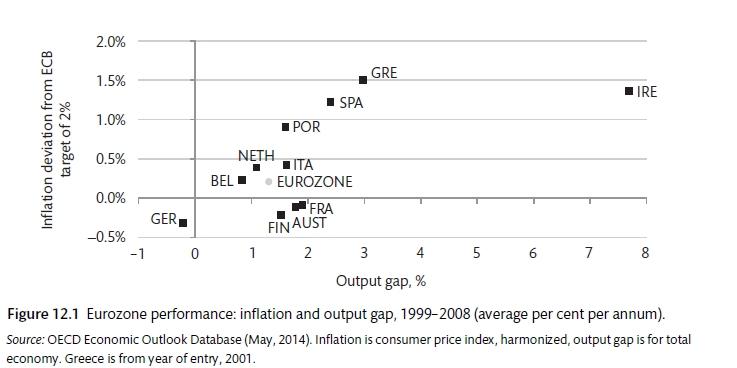

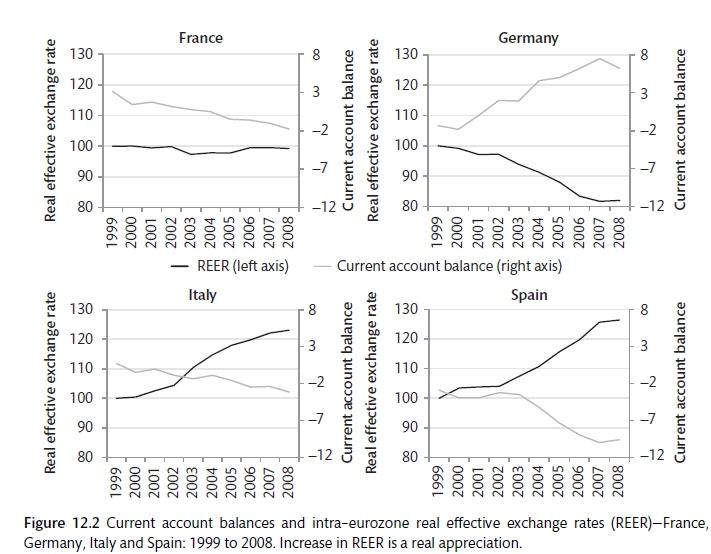

In the first 10 years the Eurozone as a whole was close to the 2.0% inflation target and the zero output gap reference. However, Ireland had much higher inflation and its economy was running beyond potential. This was also the case, to a lesser extent, for Spain, Portugal and Greece. France Italy and Spain also experienced appreciation of their real exchange rates and an increase in their currency account deficits while Germany saw a depreciation and an increased surplus. Higher than average inflation expectations also reduce the real interest rate that can tend to increase the risk of over-heating. In the currency union, the only way that a country can reverse the period of above average wage growth and loss of competitiveness is through a period of lower than average wage growth or higher than average productivity. This is essentially the opposite of the internal devaluation that was required of Ireland, Italy, Spain and Portugal in the aftermath of the GFC.

Economic divergence (Carlin and Soskice 2015)

The Maastricht Treaty that created the European single currency assigned responsibility for monetary policy to the European Central Bank (ECB) for control of inflation and control of fiscal policy was given to member governments to be used to offset country-specific shocks. The treaty also created the Growth and Stability Pact to prevent countries using fiscal policy in a way that would undermine the inflation policy of the ECB. The ECB was modelled on the German Bundesbank, the central bank of Germany, as an independent bulwark against inflation. There is an asymmetric inflation target (less than 2%). It also uses a reference growth rate of 4.5% for money supply as measured by M3. This is consistent with nominal GDP growth of 4.0% (2.0% inflation, 2.0% to 2.5% output and 0.5% decline in velocity). The Stability and Growth Pact specified that deficit to GDP be kept below 3.0% and debt to GDP below 60%. Fiscal policy in the Eurozone has not been successful as it has tended to be pro-cyclical. The Growth and Stability Pact was revised in 2005 to focus on cyclically-adjusted balanced budgets. Country-specific medium term objectives were introduced.

Real exchange rates and rebalancing (Carlin and Soskice 2015)

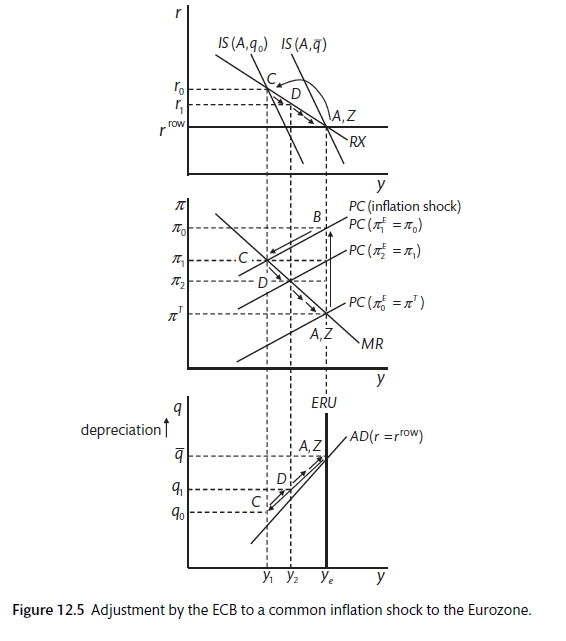

10.2 Modelling the Eurozone

There is no difference in the way that the ECB reacts to common shocks than central banks in our standard model. Country-specific shocks are equivalent to regional shocks in the standard model. We have not discussed these but we could consider a shock to the Italian economy in the same way that we think of a shock to the economy in Yorkshire from a UK perspective.

Stability with a common shock (Carlin and Soskice 2015)

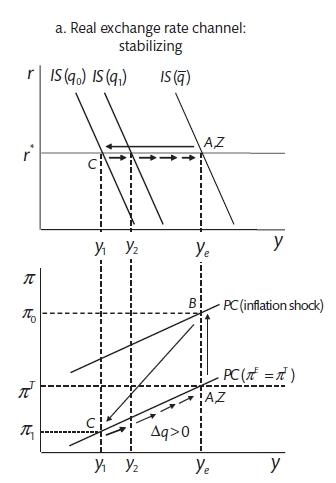

In theory, for a country-specific inflation shock there is no need for the central bank to take action as the higher level of inflation will increase the real exchange rate and bring the economy back to balance with lower exports. This is called the real-exchange rate channel of adjustment.

Real exchange rate channel (Carlin and Soskice 2015)

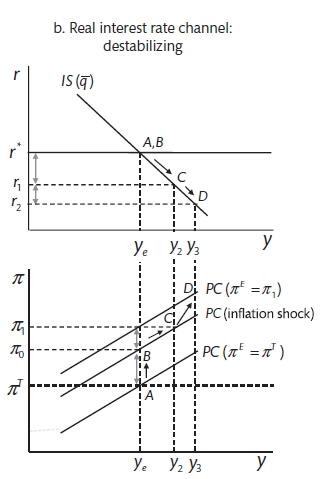

However, there is a danger that idiosyncratic changes in the expected inflation rate for individual countries can affect the real interest rate. There is conflict between the counter-cyclical real exchange rate effect and the pro-cyclical real interest rate channel. The combination of low nominal interest rates (set by the ECB) and high inflation in Spain and Ireland, together with the financial accelerator and bubble mechanisms in the housing market tipped the balance in favour of the real interest rate channel in Ireland, Spain and Portugal in the 1990s and the early years of 2000. However, it is likely now that inflation expectations are now more anchored and that the real exchange rate channel will be more powerful in the future.

Real interest rate channel (Carlin and Soskice 2015)

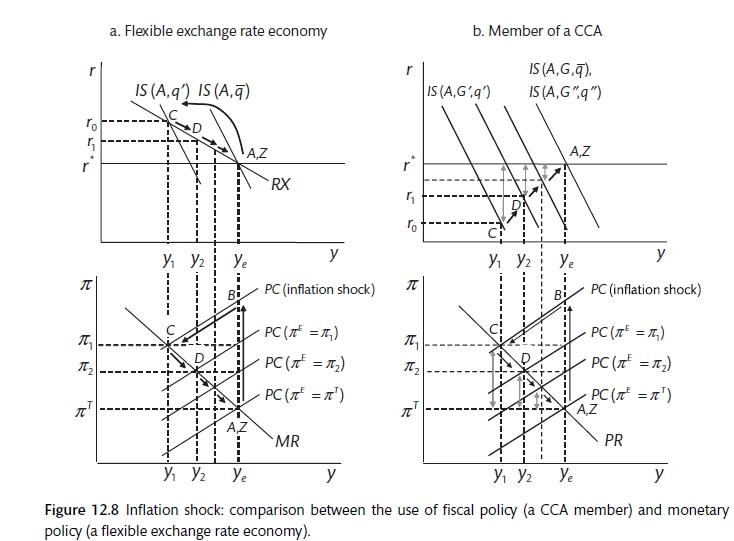

In these cases the government should use fiscal policy to provide an offset, but this is not possible with the Growth and Stability Pact. It is also possible that coordinated wage bargaining (as is common in Germany and some Scandinavian countries) could ensure that real wages adjust to economic shocks.

Use of fiscal policy for idiosyncratic shocks (Carlin and Soskice 2015)

10.2.1 The real exchange rate channel

From the Taylor Rule means that interest rates must increase by more than the increase in inflation expectations to raise the real interest rate. This is built into the central bank reaction function so that a negative output gap will dampen inflation. If this does not affect individual countries (through the real exchange rate and fiscal policy), instability can occur. This is called The Walters’ Critique after Alan Walters. There is no role for fiscal policy in the standard model. In practice, fiscal policy is a less effective means to stabilise the economy because deficit concerns may impede the use and fiscal policy is less effective under a flexible exchange rate. The effect of the real exchange rate and real interest rate channels depend on how inflation expectations are formed. If inflation expectations remain anchored at the ECB target, an inflation shock cause a real appreciation, lower exports and lower output. At the lower output, inflation falls and the economy returns to equilibrium.

\[\uparrow \pi \rightarrow \downarrow y \rightarrow \downarrow \pi \dots \text{until} \pi < \pi^T \text{when} \uparrow q \rightarrow \uparrow y\]

However, if inflation expectations are not firmly anchored (there may be a backward-looking element to inflation expectations), the real interest rate can deviate from the real interest rate set by the ECB. To simplify with no real exchange rate effect and therefore no shift in the AD curve, the fall in the real interest rate causes a shift down the AD curve and inflation expectations rise further.

\[\uparrow \rightarrow \uparrow \pi^E \rightarrow \downarrow r \rightarrow \uparrow y \pi \dots \text{destabilising}\]

The government can use fiscal policy here to prevent instability of the Walter’s critique effect; sluggish wage and price adjustment may make the real exchange rate channel slow and costly. Compare the use of fiscal policy in a common currency area (CCA) to the use of monetary policy with a flexible exchange rate. The PC MR or PR graphs are virtually the same. The use of monetary policy is the same as has been discussed before. The interest rate is set so that in combination with the appreciation of the real exchange rate, output will bring down inflation. In the second case, fiscal policy must be set so that it will reduce inflation while this rise in inflation has reduced the real interest rate alongside the effect of the real appreciation. Once the country in the CCA has inflation down to the target, prices will be higher and there remains a real appreciation. Therefore, government spending must offset the permanent damage to net exports. There are twin deficits. For a negative aggregate demand shock, it is the opposite for the CCA country: government spending is increased to eliminate the output gap. Once the economy returns to equilibrium, the real exchange rate will be depreciated and there is a primary budget deficit.

10.3 Eurozone governance, sovereign risk and banking

The GFC caused a reassessment of risk. As a result, after 2008 attention turned to the credit risk of individual EMU governments. The UIP formula had to be modified

\[i = r^* + (log e^E_{t+1} - log e_t) + \rho_t\]

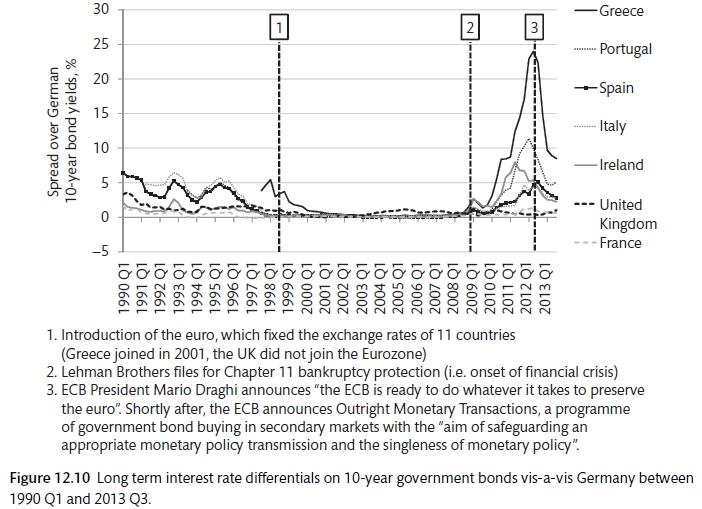

There are two parts to the bond risk: exchange rate risk and default risk. The exchange rate risk was removed with the introduction of the single currency. Figure 12.2 has a good overview of the convergence process followed by the increase in spreads between periphery bonds and those of the benchmark Germany with the key dates. Default risk had been ignored before the financial crisis because: the possibility of a default by an EU government was considered to be very small; the divergent performance of economies was not linked to possible implications for government solvency; the non-bailout clause was not believed. The GFC meant that investors suddenly started to look at the fiscal implications of supporting insolvent banks.

Divergence and default risk (Carlin and Soskice 2015)

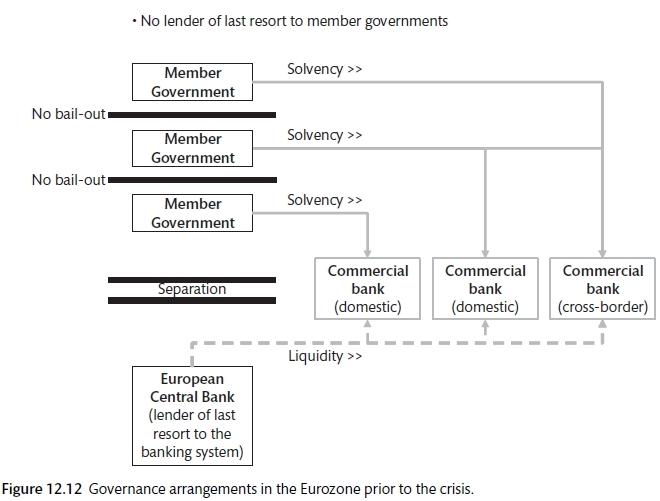

There were three aspects to the EMU Governance arrangements that were created under the Maastricht Treaty: Governments would not bail out other governments (this is the no bail-out clause); ECB would not finance governments (would not provide credit to governments); the fiscal rules of the Growth and Stability Pact. While the US central bank (The Fed) and the ECB provide liquidity to the banking system, there are much smaller fiscal transfers across EU states and individual counties in the European Union are responsible for their own banking system. This is a key difference. In the US the Federal Government is responsible for the banking system no matter which state the bank is located. In the Eurozone, the individual countries have to look after their own banks.

The structure of central banks, government and commercial banks is very different in the Eurozone to that of counties with their own independent central bank. While in each case the central bank will act as a lender of the last resort and provider of liquidity for the banking system and the government is responsible for supporting banks that find themselves insolvent. The ECB cannot provide support to individual governments and act as a lender of the last resort to them. As such, there can a rise a concern that governments may find themselves illiquid when they try to roll over their debts. In that case the rise in borrowing costs (to protect investors against liquidity) will can be sufficient to cause a self-fulfilling crisis.

EU governance (Carlin and Soskice 2015)

There is a close link between banks and the government because banks tend to hold a large amount of government bonds. This is a core (safe) asset. The percentage of government bonds held by commercial banks was 28.3%, 27.3% and 22.9% in Spain, Italy and Germany. The equivalent for the UK and the US was 10.2% and 2.0% respectively. This is a vicious circle: when bond prices fall sharply, banking solvency is called into question; when banks appear to be insolvent, government finances are questioned. As there was no Eurozone Bank Resolution system, national governments were forced to deal with banking problems themselves. In some cases (Ireland) the banks were large relative to the size of the country. The Bank of Ireland had assets equal to 99% of Irish GDP. However, Bank of America has assets equal to only 12% of US GDP (but equal to 431% of the GDP of North Carolina) (OECD 2011). The Eurozone case is complicated by the fact that some banks have cross-border presence and may be the responsibility of more than one government.Government spending and public debt are much higher in Eurozone countries than they are in US states.

OECD Economic Outlook can be read here. There is also access to data.

Since 2010 the EU have been trying to address some of the governance issues that have caused the crisis. The no bail out clause was broken and money was lent to Ireland and Greece in return for the imposition of austerity.