Chapter 17 Data Scraping

library(tidyverse) # loading ggplot2 and dplyr

library(rvest) # rvest is not loaded in the tidyverse MetapackageDr. Sonderegger’s Video Companion: Video Lecture.

Getting data into R often involves accessing data that is available through non-convenient formats such as web pages or PDFs. Fortunately those formats have common structures that allow one to obtain and import data. However to do this, we have to understand a little bit about those file formats. This chapter helps to collect data from public online sources, a practice commonly known as scraping data. We will focus on scraping data from webpages, with the largest goal being taking data stored in html tables. There are many extensions to this, some of which have tools that have aged a bit. A very useful and generalized tool for obtaining data from html formats is the Selenium suite of packages, available for R and Python (requires Java). Another common goal is to scrape information out of PDFs, of which there are significant tools for PDF Data Extraction (PDE).

The content below will focus on web scraping using some simple Tidyverse tools. Although these tools are useful, packages like rvest are quite limited in comparison to Selenium. Especially now that the SelectorGadget, discussed below, is limited on which web pages it can operate.

17.1 Web Pages & HTML

Posting information on the web is incredibly common. A common first approach is to use a search engine, like Google, to find answers to our problems. It is inevitable that we will want to grab at least some of that information and import it as data. There are several ways to go about this:

Human Copy/Paste - Sometimes it is easy to copy/paste the information into a spreadsheet. This works for small data sets, but sometimes the HTML markup attributes get passed along and suddenly “by-hand” data import becomes very cumbersome for more than a small amount of data. Furthermore, if the data is updated, we would have to redo all of the work instead of just re-running or tweaking a script.

Download the page, parse the HTML, and select the information you want. The difficulty here is knowing what you want in the raw HTML tags.

This is not an HTML chapter nor is HTML a course objective of this course. Knowing how web pages are generated is certainly extremely helpful in this endeavor, but is not absolutely necessary. It is sufficient to know that HTML has open and closing tags for things like tables and lists. Below is some sample HTML that would generate a simple table. Notice there are many tags, identifying different attributes of the table, but we will take advantage of the “table” attribute.

# Example of HTML code that would generate a table

# Table Rows begin and end with <tr> and </tr>

# Table Data begin and end with <td> and </td>

# Table Headers begin and end with <th> and </th>

<table style="width:100%">

<tr> <th>Firstname</th> <th>Lastname</th> <th>Age</th> </tr>

<tr> <td>Derek</td> <td>Sonderegger</td> <td>46</td> </tr>

<tr> <td>Robert</td> <td>Buscaglia</td> <td>40</td> </tr>

</table>Similarly, maybe our data is stored in a list. You can notice some commonality of the attributes below, that identify the use of an unordered list and the elements within the list.

# Example of an unordered List, which starts and ends with <ul> and </ul>

# Each list item is enclosed by <li> </li>

<ul>

<li>Coffee</li>

<li>Tea</li>

<li>Milk</li>

</ul>Given this structure is relatively clear and highly conserved on webpages, it should not be too hard to grab tables or lists from a web page. However HTML has a hierarchical structure so that tables could be nested in lists. In order to control the way the page looks, there is often a lot of nesting. For example, we might be in a split pane page that has a side bar, and then a block that centers everything, and then some style blocks that control fonts and colors. Add to this, the need for modern web pages to display well on both mobile devices as well as desktops and the raw HTML typically is extremely complicated. This is where some of the tools mentioned at the beginning of this chapter have a leg-up, as they can help you navigate into complex structures with ease, select the elements you want, and extract them. However, we want to develop a simple workflow for obtaining the data we are interested in, without having to use a very complex tool like Selenium.

In summary the workflow for scraping a web page will be:

- Find the webpage you want to pull information from.

- Download the html file.

- Parse it for tables or lists (this step could get ugly!).

- Convert the HTML text or table into R data objects.

We can use the tidyverse to make these above steps relatively simple. Hadley Wickham wrote a package to address the need for web scraping functionality and it happily works with the pipelines we have studied throughout this textbook. The package rvest is intended to harvest data from the web and make working with html pages relatively simple. This tool has worked extremely well for this course, but with some of the unintended problems now occurring with the companion tool known as the SelectorGadget, obtaining any element from a webpage is not quite as easy as it used to be. We want to make sure we can scrape data out of a table, and we will leave some of the other details, like obtaining text data directly from a website, as an advanced topic.

17.1.1 Example Wikipedia Table

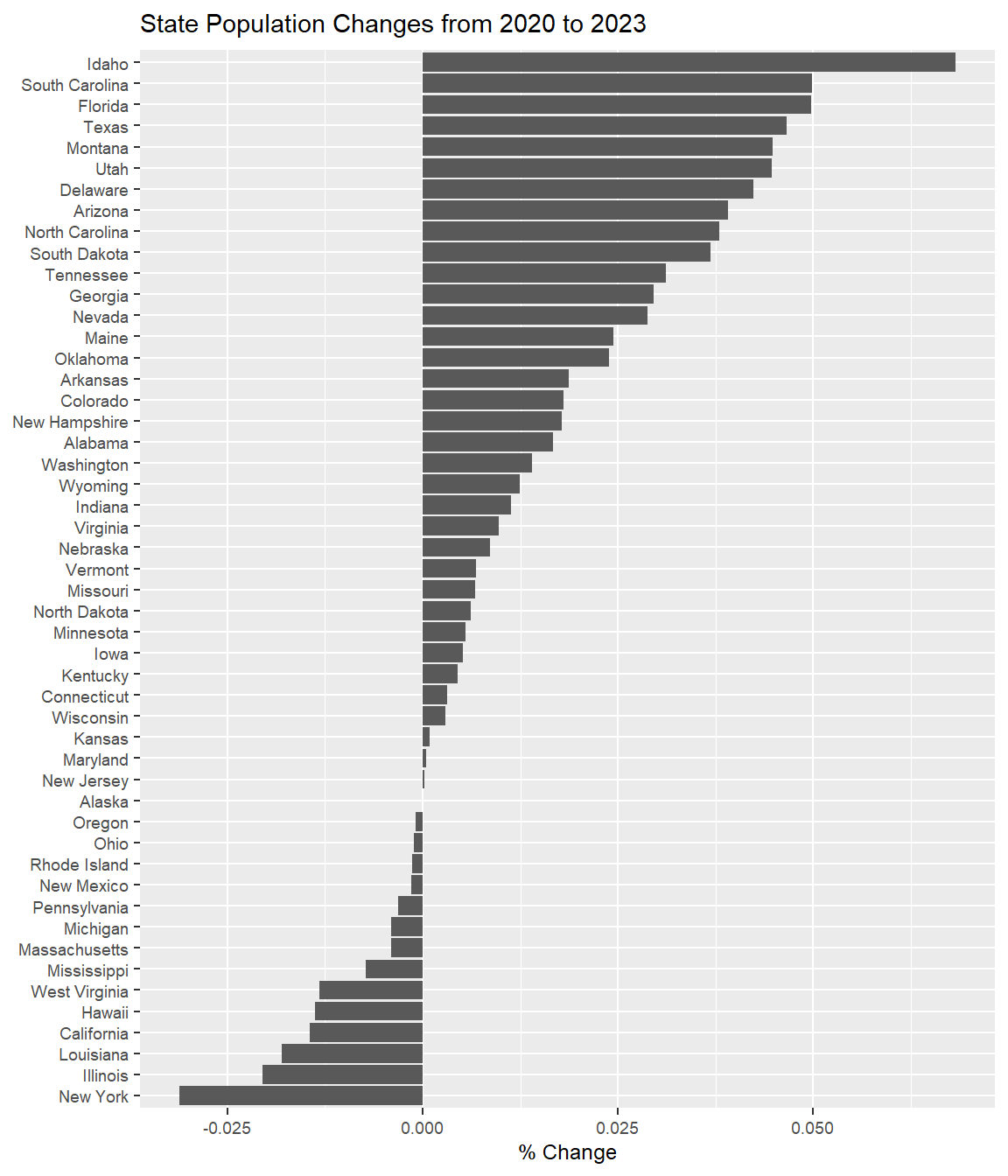

Lets consider the U.S. state population sizes. Maybe we would like to know some recent trends in population sizes, so we might start with a a quick Google of some key terms. Doing so, as we all commonly know, might bring up a Wikipedia page on US Populations. If we view this webpage, we observe there is some interesting data regarding the population of the U.S. in many different ways. This might be a page we would like to obtain some data from and consider making an interesting graphic regarding recent trends in U.S. populations.

Continuing our workflow for web scraping, our next step would be to download the html file. This functions below are all part of the rvest package, which needs to be loaded to run the code below. First, we create an R object that contains the URL of the webpage we are interested in obtaining information from, we then read this html data using the command read_html, which essentially reveals all the components available on the webpage. It can be useful to explore these objects on your own terminal, but some have very large outputs not suitable for the web output of this textbook.

url = 'https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_states_and_territories_of_the_United_States_by_population'

# Download the web page and save it. I like to do this within a single R Chunk

# so that I don't keep downloading a page repeatedly while I am fine tuning

# the subsequent data wrangling steps.

page <- read_html(url)Now that we have all the elements of the webpage ready for further processing, we can start to extract specific elements. This is where we might like to use some advanced css elements that the SelectorGadget used to be very helpful in doing. Ignoring advanced elements for now, we discussed above that elements like tables and lists have a simple common structure that are easy to find. So the next step would be to identify these “nodes” within the HTML. Thus, below uses the html_nodes command to extract any elements that have the “table” attribute. This identifies the \(6\) tables present on the Wikipedia page of interest. Now would be a good time to compare the output below to what you observe on the wiki page above.

# Once the page is downloaded, we need to figure out which table to work with.

# There are 5 tables on the page.

page %>%

html_nodes('table') ## {xml_nodeset (6)}

## [1] <table class="sortable wikitable sticky-header-multi static-row-numbers s ...

## [2] <table class="wikitable"><tbody>\n<tr><th style="text-align:left">Legend\ ...

## [3] <table class="wikitable sortable" style="text-align:right">\n<caption>Pop ...

## [4] <table class="nowraplinks hlist mw-collapsible autocollapse navbox-inner" ...

## [5] <table class="nowraplinks navbox-subgroup" style="border-spacing:0"><tbod ...

## [6] <table class="nowraplinks hlist mw-collapsible mw-collapsed navbox-inner" ...It might not be immediately obvious where all of these tables are on the wiki page. If we look at the “class” of each table element, notice that are some are actual tables, either sortable or not, and that the final three tables are actually the way the links at the end of the Wikipedia page are nicely collated. The next goal is to decide which of these tables is our table of interest. With six tables on the page, we should go through each table individually and decide if it is the one that we want. To do this, we’ll take each table and convert it into a data frame and view it to see what information it contains.

# This chunk can be a gigantic pain because anybody can edit Wikipedia pages.

# Depending on who edits the page, sometimes elements change within the page.

# At the time of writing the current version of this book, the code below should display

# the output of a population table containing many territories and states.

# Depending on who edits the page, sometimes the names change, column orientations

# are changed, or even the order of tables change. This is why we must explore

# the page and ensure we are getting the information we want!

page %>%

html_nodes('table') %>%

.[[1]] %>% # Grab a particular table - we are interested in [[1]]

html_table(header=FALSE, fill=TRUE)## # A tibble: 62 × 11

## X1 X2 X3

## <chr> <chr> <chr>

## 1 State or territory Census population[8][a] Census population[8][a]

## 2 State or territory July 1, 2023 (est.) April 1, 2020

## 3 California 38,965,193 39,538,223

## 4 Texas 30,503,301 29,145,505

## 5 Florida 22,610,726 21,538,187

## 6 New York 19,571,216 20,201,249

## 7 Pennsylvania 12,961,683 13,002,700

## 8 Illinois 12,549,689 12,812,508

## 9 Ohio 11,785,935 11,799,448

## 10 Georgia 11,029,227 10,711,908

## X4 X5 X6 X7

## <chr> <chr> <chr> <chr>

## 1 Change,2010–2020[8][a] Change,2010–2020[8][a] House seats[b] House seats[b]

## 2 % Abs. Seats %

## 3 6.13% 2,284,267 52 11.95%

## 4 15.91% 3,999,944 38 8.74%

## 5 14.56% 2,736,877 28 6.44%

## 6 4.25% 823,147 26 5.98%

## 7 2.36% 300,321 17 3.91%

## 8 −0.14% −18,124 17 3.91%

## 9 2.28% 262,944 15 3.45%

## 10 10.57% 1,024,255 14 3.22%

## X8 X9 X10 X11

## <chr> <chr> <chr> <chr>

## 1 Pop. perelec. vote(2020)[c] Pop.perseat(2020)[a] % US(2020) % EC(2020)

## 2 Pop. perelec. vote(2020)[c] Pop.perseat(2020)[a] % US(2020) % EC(2020)

## 3 732,189 760,350 11.800% 10.04%

## 4 728,638 766,987 8.698% 7.43%

## 5 717,940 769,221 6.428% 5.58%

## 6 721,473 776,971 6.029% 5.20%

## 7 684,353 764,865 3.881% 3.53%

## 8 674,343 753,677 3.824% 3.53%

## 9 694,085 786,630 3.521% 3.16%

## 10 669,494 765,136 3.197% 2.97%

## # ℹ 52 more rowsI kept the code above flexible so you can try changing which table is extracted and try to align it with what is on the webpage if you are interested. If you change the [[1]] to another value between 1 and 6, you will grab the different tables identified when we extract the nodes containing the table attribute. It is not to difficult to align these with the tables you see on the webpage. After some trial and error, you should agree that the table of interest is the first table in our list of nodes.

The next thing we might like to do is extract and begin cleaning up the data table for use in R. The code below uses some code that should be a bit more familiar at this stage of the course. Run any of the code below, viewing smaller pipelines to explore what each line of code is doing.

# Create a data object, removing the first two rows which contain the rather complicated

# column names. We will put on better column names in a moment.

State_Pop <-

page %>%

html_nodes('table') %>%

.[[1]] %>% # Grab the first table and

html_table(header=FALSE, fill=TRUE) # convert it from HTML into a data.frame

head(State_Pop)## # A tibble: 6 × 11

## X1 X2 X3

## <chr> <chr> <chr>

## 1 State or territory Census population[8][a] Census population[8][a]

## 2 State or territory July 1, 2023 (est.) April 1, 2020

## 3 California 38,965,193 39,538,223

## 4 Texas 30,503,301 29,145,505

## 5 Florida 22,610,726 21,538,187

## 6 New York 19,571,216 20,201,249

## X4 X5 X6 X7

## <chr> <chr> <chr> <chr>

## 1 Change,2010–2020[8][a] Change,2010–2020[8][a] House seats[b] House seats[b]

## 2 % Abs. Seats %

## 3 6.13% 2,284,267 52 11.95%

## 4 15.91% 3,999,944 38 8.74%

## 5 14.56% 2,736,877 28 6.44%

## 6 4.25% 823,147 26 5.98%

## X8 X9 X10 X11

## <chr> <chr> <chr> <chr>

## 1 Pop. perelec. vote(2020)[c] Pop.perseat(2020)[a] % US(2020) % EC(2020)

## 2 Pop. perelec. vote(2020)[c] Pop.perseat(2020)[a] % US(2020) % EC(2020)

## 3 732,189 760,350 11.800% 10.04%

## 4 728,638 766,987 8.698% 7.43%

## 5 717,940 769,221 6.428% 5.58%

## 6 721,473 776,971 6.029% 5.20%Nice! Now this is starting to look like some usable information, just need to do some more data cleaning. The first two rows are just telling us information about each column, and the names are not that useful for data cleaning purposes. There are also a lot of interesting columns, but for our purposes of exploring U.S. population trends, really on the the first three are useful. Lets simplify the data we have scraped and do some simple column naming. Put simply, the code below removes unnecessary rows and columns, does some renaming to make elements more usable, and then outputs the data table as a tibble.

# There are a lot of interesting columns, but we really only need the first 3.

# While we are at it, lets give them simple names to use below.

State_Pop <- State_Pop %>%

slice(-1 * 1:2 ) %>%

select(1:3) %>%

magrittr::set_colnames( c('State', 'Population2023','Population2020') )

# To view this table, we could use View() or print out just the first few

# rows and columns. Converting it to a tibble makes the printing turn out nice.

State_Pop %>% as_tibble() %>% head()## # A tibble: 6 × 3

## State Population2023 Population2020

## <chr> <chr> <chr>

## 1 California 38,965,193 39,538,223

## 2 Texas 30,503,301 29,145,505

## 3 Florida 22,610,726 21,538,187

## 4 New York 19,571,216 20,201,249

## 5 Pennsylvania 12,961,683 13,002,700

## 6 Illinois 12,549,689 12,812,508Starting to look in good shape, now we do our more common data cleaning tasks. We cannot analyze numerical data when it is in a string format, so we should do some string manipulation to convert everything in these tables into proper numeric values. Also, the rows for the U.S. territories have text that was part of the footnotes. So there are [7], [8], [9], and [10] values in the character strings. We need to get rid of all those commas, remove any strange trailing information for footnotes, and convert to numeric. There are some elements within the table that were blank to begin with, so these are now “NA” in our data frame. If you run the code on your own terminal, you might notice some warnings regarding how these values were handled, but they are observation rows of interest to our problem.

State_Pop <- State_Pop %>%

select(State, Population2023, Population2020) %>%

mutate_at( vars(matches('Pop')), str_remove_all, ',') %>% # remove all commas

mutate_at( vars(matches('Pop')), str_remove, '\\[[0-9]+\\]') %>% # remove [7] stuff

mutate_at( vars( matches('Pop')), as.numeric) # convert to numbersWe are close to making a pretty neat graph, but there are a lot of “State” rows that are not actually states. The work I have hidden from you was that I extract all the rows of the “State” column and created the vector of strings you see below. This vector contains all of the “State” rows that are not meaningful to the analysis of each individual U.S. states, so they are removed in the filter process. It seemed like a graph of the change in state population over the three years of data provided would be interesting, so a new column is created for this information. Then those usual data cleaning steps are present, specifically some factorizing and reordering. To make our graph interesting, the states have been ordered by their change in population from 2020 to 2023.

State_Pop <- State_Pop %>%

filter( !(State %in% c('Puerto Rico', 'District of Columbia', 'Guam[10]',

'U.S. Virgin Islands[11]', 'American Samoa[12]',

'Northern Mariana Islands[13]', 'The 50 states',

'The 50 states and D.C.', 'Total US and territories',

'Contiguous United States') ) ) %>%

mutate( Percent_Change = (Population2023 - Population2020)/Population2020 ) %>%

mutate( State = fct_reorder(State, Percent_Change) )And just to show off the data we have just imported from Wikipedia, we’ll make a nice graph.

ggplot(data = State_Pop, aes(x=State, y=Percent_Change)) +

geom_col( ) +

labs(x=NULL, y='% Change', title='State Population Changes from 2020 to 2023') +

coord_flip() +

theme(text = element_text(size = 9))

Pretty amazing what we can learn by extracting information from web pages!

17.1.2 Lists

Unfortunately, we don’t always want to get information from a webpage that is nicely organized into a table. Suppose we want to gather the most recent thread titles on Digg. This choice was made because the SelectorGadget still works on this page. Unfortunately it no longer works on Reddit. For exploratory purposes, this website will work, but this textbook does not affiliate with any of the politics or articles that may be present if you run the code below!

We could sift through the HTML tags to find something that will match, but that will be challenging. Instead we will use a CSS selector tool created by the tidyverse group known as the SelectorGadget.

Selector Gadget

The selector gadget is a simple tool that will allow us to access any element on a website (where it works). The selector allows a “point-and-click” method to extracting CSS elements. To install the bookmarklet, simply drag the following javascript code (should appear as a link) onto your bookmarks toolbar within your web browser.

We are now ready to use the CSS selector tool. As per the current edition of this textbook, the newest version of the selector still works on a wide variety of webpages, although occasionally it just times out and does not properly start up. When you are at the site you are interested in, just click on the SelectorGadget javascript bookmarklet to engage the CSS engine. It will take a moment to load up and then what looks like a small output bar will appear near the bottom of your webpage.

To use the gadget, we must select the elements on the page we are interested in. If you use the Digg site for practice, notice that when you click on an article headline, it highlights the first in green, indicating this is the structure it is looking for on the page. Many other elements on the page will then be highlighted in yellow. These are the elements that match the properties you selected with your click, but sometime other elements have similar attributes. This can happen because of elements like ads or sidebars. We can click off any elements we do not want to select, and when they are clicked on they should turn RED to indicate they will not be selected. Once the green and yellow highlights seem to be ONLY on the elements are you are interested in, you are ready to copy the tag that was found from the selector gadget.

As one last note: things highlighted in green are things you clicked on to select, stuff in yellow is content selected by the current html tags, and things in red are things you chose to NOT select. Try it now with the following site, if you would like!

With the site loaded, it needs to be told what “nodes” do we want to extract. After some selection with the CSS selector tool, this page had a simple node structure just called “.headline”. This can then be fed into the html_nodes command. Because in this section we are interested in only the text of the headlines, this information is sent to the command html_text(). Notice this is not the same command that was used for tables, and many exist within the rvest package.

# Once the page is downloaded, we use the SelectorGadget Parse string

# To just give the headlines, we'll use html_text()

HeadLines <- page %>%

html_nodes('.headline') %>% # Grab just the headlines

html_text() # Convert the <a>Text</a> to just Text

HeadLines %>%

head()## [1] "\n These Are America's Most Popular Business Figures\n "

## [2] "\n Justin Bieber's New York Neighborhood Has A Unique Plus Side For Pop Stars\n "

## [3] "\n Watching A Corn Syrup-Filled Balloon Pop In Slow Motion Is More Gross Than You'd Think\n "

## [4] "\n Why That 'Dry Skin' Around Your Eyebrows Isn't What You Think\n "

## [5] "\n Here's Where Jeffrey Epstein's Island Visitors Came From In The US\n "

## [6] "\n The Best Multiplayer Games To Play This Thanksgiving Break\n "The headlines you extract might not be the same as those above, since the webpage will be loaded to your live R studio version! String manipulation could then be applied to these headlines, to simplify them down to a vector of strings we are used to. For example, maybe we want to get rid of all the white space before and after the actual headline. I have output only the first \(6\) headlines on the day the book is compiled.

## [1] "These Are America's Most Popular Business Figures"

## [2] "Justin Bieber's New York Neighborhood Has A Unique Plus Side For Pop Stars"

## [3] "Watching A Corn Syrup-Filled Balloon Pop In Slow Motion Is More Gross Than You'd Think"

## [4] "Why That 'Dry Skin' Around Your Eyebrows Isn't What You Think"

## [5] "Here's Where Jeffrey Epstein's Island Visitors Came From In The US"

## [6] "The Best Multiplayer Games To Play This Thanksgiving Break"Sometimes the headlines can contain additional information. Unfortunately the Digg headlines no longer have the links embedded, so the code below does not show an interesting output in this case. However, if the headlines did have specific attached attributes, such as “href”, these attributes could be extracted directly with the html_attr() function. I have retained the code below, but if will not properly extract anything at this time, as the headlines no longer have attached attributes (but might on other webpages!).

17.2 Future Content

Unfortunately, due to time spent on updating this chapter to get the basics done, there will not be any advanced topics added just yet. I am leaving some headers for content that I would like to develop in a later update.

17.3 Exercises

Exercise 1

At the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety, they have data about human fatalities in vehicle crashes. From this web page, import the data from the Fatal Crash Totals data table and produce a bar graph gives the number of deaths per 100,000 population for each state. Do not include the provided “U.S. Totals” and be sure to order your graph by fatal crashes. Be sure to use the correct table!

As we are at the advanced topics sections, here is what you should accomplish in no particular order. The only required output here is the code and a finalized bar graph. Since these are not “sub-questions” they have been labeled with roman numerals instead.

(i) Extract the correct data table.

(ii) Clean the data table extracted. Remove unnecessary columns and rows, rename columns for easier use in R, convert all numerical data to numbers!

(iii) Create a bar graph that is clear and legible in your PDF output. Properly orient and name the axes so they are legible (you may choose the direction of the graph). You can resize the graph with R-chunk options such as fig.height and fig.width. Ensure the axes are properly labeled, give your graph a title, change text elements as necessary (described in Chapter 14).

(iv) Ensure the code used for data scraping from the web, data cleaning, and making the graph is all present and readable on your PDF! Ensure the graph is easy to read!

Exercise 2

From the same IIHS website, complete the same work as Exercise 1 but now containing additional data using related to seat belt use. To strengthen our data wrangling skills, we will want to join the Fatality data (Exercise 1) with the seat belt provided in another table on the same webpage. Specifically you want to extract and join with your fatality data from Exercise 1 the column related provided the Percent of Observed Seatbelt Use”.

Create a new data frame, joining together your two data tables, and use this new data to make a scatter plot of percent seat belt use vs number of fatalities per 100,000 people. Follow the same steps as provided in Exercise 1!

Exercise 3

One of my favorite blogs is known as Towards Data Science. From the Towards Data Science homepage, extract the most recent threads. Be sure you only get as many threads as possible above the section labeled “About”. Hint. You will need to use the SelectorGadget to get the correct elements, following the steps shown above for extracting a “list”. Show all recent threads rvest is capable of extracting (do not truncate to the head). You are not required to clean up the thread headlines in any way, in case some strange headline output is obtained.