3.1 Uncertainty Management Theories

3.1.1 Problematic Integration Theory

Problematic Integration (PI) theory: From the theories of planned behavior and reasoned action, we believe that we can predict people’s behaviors because people are assumed to be “rational.” However, there are communication substance that could input uncertainty and inconsistency expectations to predict human behavior.

Goals:

- find important and ubiquitous communication process

- increase sophistication

- encourage other ways of understanding

- increase communicators’ empathy and compassion.

Forms of PI:

- Uncertainty

- Diverging expectations and desires

- Ambivalence

- Impossible desires (theoretical vs. practical impossibility).

Discussion regarding PI can deepen or hurt relationships

Encounter PI, we can engage in presentational and avoidance rituals.

PI defines uncertainty as “difficulty forming a mental association.” (Babrow and Matthias 2009)

- form-specific adaptation of messages means “communicating in ways that speak to the precise dilemma.” (Babrow and Matthias 2009)

3.1.2 Uncertainty Management Theory

Uncertainty Management (UM)

Based on two post-positivist sources:

- Uncertainty reduction theory (BERGER and CALABRESE 1975): managing uncertainty

- Cognitive theory of uncertainty in illness (Mishel 1990): depending on context, uncertainty can be either good or bad

Uncertainty must be appraised.

Notion of management = control

Research and practical application (e.g., health, education, )

Evaluation: not achievable under post-positivist because of its blurry boundary conditions. But under interpretivist, it

can make more sense due to its contextual meanings.

Application:

Taking Control: The Efficacy and Durability of a Peer-Led Uncertainty Management Intervention for People Recently

Diagnosed With HIV (Brashers et al. 2016): Uncertainty management need to be adaptable. Due to the changing nature of HIV

skills and information for patients need to be communicated continuously. Supported by the theories of social support,

uncertainty management can be facilitated with peer support. participant report less illness-related uncertainty,

greater access to social support, and more satisfaction with the social support compared to the control group. Illness

uncertainty was assessed with (MISHEL 1981).

Example

(SHARABI and CAUGHLIN 2017) Effects of the first FtF date on romantic relationship development:

- Relational choice models of romantic relationships: Choosing partners that make the most sense to you (fit an image of an ideal mates).

- Disillusionment models of romantic relationship: When you see other’s aspects (e.g., personality, behaviors) of your partner, you might no longer be interested in your partner.

Predicting first date success in online dating

- Similarity and uncertainty as predictors: users want to reduce uncertainty before meeting offline.

- Communication as moderating role.

Interestingly, people disclose more deeply online compared to offline (Tidwell and Walther 2002)

3.1.3 Theory of Motivated Informaiton Management (TMIM)

Born from the frustration with Problematic Integration Theory, Uncertainty Management Theory interepretivist orientation, and desire to incorporate individual experience’s complexity with uncertainty and predictive specificity.

The theory has its basis on:

- Subjective Expected Utility theory (Fischhoff, Goitein, and Shapira 1983)

- social Cognitive theory (Locke and Bandura 1987)

- Theories of bounded rationality (Kahneman 2003): People make suboptimal choice due to other emotions and bias factors.

Due to its laborious process of decision, theory of motivated information management only applies to cases where the person thinks a decision is sufficient important.

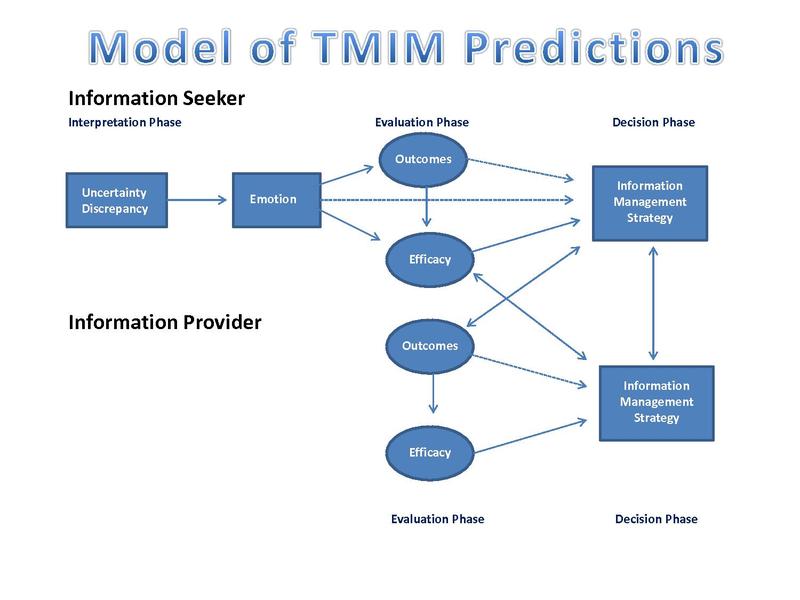

Phases:

Interpretation Phase: recognize the difference (called uncertainty discrepancy) in desired uncertainty and current uncertainty, which mostly produces anxiety, but sometimes hope, anticipation, anger.

Evaluation Phase: :appraisal of uncertainty impacts assessments made in the evaluation phase", which makes you think about

Outcome expectancy: what happen if you search for more info

Efficacy: whether you are able to do the search.

- Communication efficacy: whether a person has the skill to seek info.

- Target efficacy: whether the target of the info search actually has and would be willing to share it.

- Coping efficiency: whether a person could emotionally, relational, or financially deal with what he or she expects to learn.

- Communication efficacy: whether a person has the skill to seek info.

Decision Phase: people are likely to seek info when they expect positive outcomes with high levels of efficacy.

## Warning: package 'jpeg' was built under R version 4.0.5

(picture from (L. Baxter and Braithwaite 2008))

Note: Information providers go through the same process with only the latter two phases (evaluation and decision).

Research and Practical Application: (e.g., education, health)

Evaluation:

Benefits:

- Draw attention to communication efficiency, and outcome expectancy

- Good theory: based on testability, heuristics, parsimony, scope condition

Improvement:

- may need to include efficacy’s strength as mediator. Depending on the positivity or negativity of expectations. relationship between outcome expectancies and efficacy, and between outcome expectancies and information seeking may differ

Example:

(Morse et al. 2013) social networks and information seeking influence drug use. From Social Cognitive Theory, and Cognitive Developmental Theory, social norms and peer influence serve as bases for aversive behaviors to be accepted. According to (Wolfson 2000), false consensus support can help explain students overestimate of the positive attitudes of their social network supported by the fact that they are uncertain about their social network’s opinions.