22 Hypothesis Testing

22.1 Hypothesis Testing Logic

The statistical inference procedure of hypothesis testing is similar in logic to the mathematical technique of proof by contradiction. The proof that there are an infinite number of prime numbers is a prime example (sorry). A proof by contradiction begins with an assumption that is the opposite of what you wish to show: There are only a finite number of prime numbers. Beginning with this assumption, we then make deductions until arising at a contradiction. If there are only a finite number of prime numbers, we may construct a number \(x\) which is one plus the product of all prime numbers. This number \(x\) is not a multiple of any of the prime numbers (they all have a remainder of one). So, either \(x\) is prime, or it is the product of prime numbers larger than the maximum prime number. In either case, there exists a prime number larger than the maximum prime number, a contradiction. The mathematical conclusion is that the assumption is false, so it’s opposite is true: there are an infinite number of prime numbers.

The logic of hypothesis testing is a weaker, probabilistic argument. Here is an example using the chimpanzee prosocial choice experiment where one chimpanzee made the prosocial choice in 60 of 90 trials with a partner.

State a model for the data:

\[ X \sim \text{Binomial}(90,p) \] where \(X\) is the number of prosocial choices and \(p\) is the probability that an individual trial is the prosocial choice.

State hypotheses:

The null hypothesis, which we are seeking evidence to discredit, is \(p = 0.5\), which corresponds to the assumption in the proof by contradiction analogy. The alternative hypothesis, is what we conclude if there is sufficiently strong evidence against the null hypothesis. We often write these in the following manner.

\(H_0:\, p = 0.5\)

\(H_A:\, p \neq 0.5\)

Note that here we will find evidence against the null hypothesis if the observed number of prosocial choices is either much larger or much smaller than expected when the null hypothesis is true.

Declare a test statistic:

A test statistic is a numerical value which may be calculated from the sample data. There may be more than one reasonable choice for a test statistic. Here, we simply pick the value of \(x\), the number of prosocial choices. We might have picked \(\hat{p} = x/n\), the proportion of prosocial choices made. Here, we are considering both \(X\), a random variable we imagine the test statistic taking were the experiment to be replicated and \(x=60\), the actual realized value.

Determine the null sampling distribution of the test statistic:

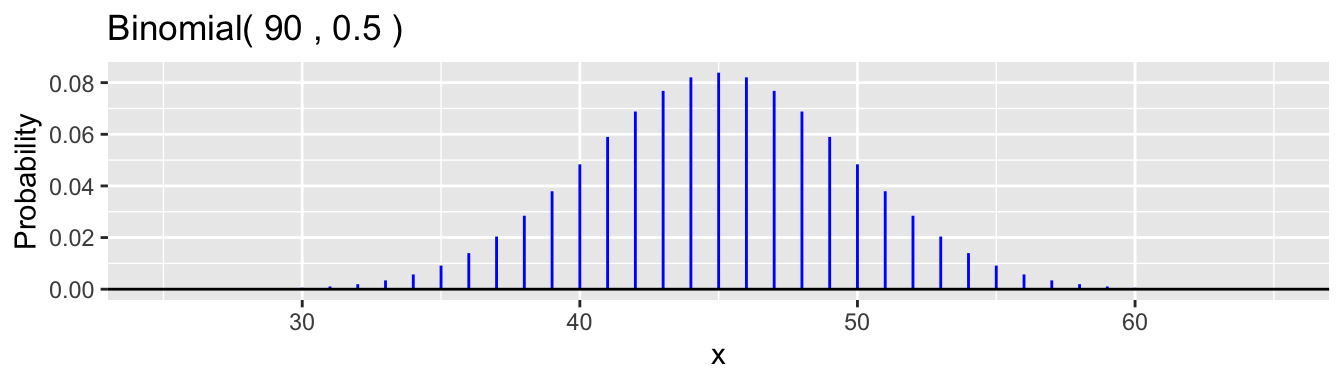

The null sampling distribution of the test statistic in this example is

\[ X \sim \text{Binomial}(90,0.5) \]

If the null hypothesis is true, then we expect that \(X\) will be close to the mean value of \(\mu = 90 \times 0.5 = 45\). How close? Well the standard deviation is \(\sigma = \sqrt{90(0.5(1-0.5)} \doteq 4.74\), so values from 40 to 50 are not very unusual. In fact, as the binomial distribution resembles a normal density here (the expected number of successes and failures are both more than ten, as one rule of thumb), we would expect about 95% of the time that \(35 < X < 55\) is we go plus and minus two standard deviations. Here is a plot.

The 0.025 and 0.975 quantiles are 36 and 54. \(\mathsf{P}(36 \le X \le 54) \doteq 0.955\).

If the null hypothesis were true and we conducted the experiment once, there is a chance that \(X\) would be far from 45, but most of the time (more than 95%, here), it will be in the interval from 36 to 54.

Calculate a p-value:

The observed test statistic is \(x = 60\). From the graph, we see this is an unusual observation. But how unusual? We could calculate \(\mathsf{P}(X=60) \doteq 0.00054\). But this is just a single outcome. The p-value is defined as the probability of observing the test statistic we did (\(x = 60\)) or any other value which would provide at least as strong as evidence against the null hypothesis, assuming that the null hypothesis is true. Here, if we had observed 61, 62, or any value up to 90, each of these results would have been even stronger evidence against the null hypothesis that \(p = 0.5\). Why? Both because the corresponding sample proportions are even further away from 0.5 than \(\hat{p} = 60/90 \doteq 0.667\) is and because their probabilities under \(H_0\) are even smaller than \(\mathsf{P}(X = 60)\). But as we also would have claimed evidence against the null hypothesis if we had observed, say \(x=30\) (the chimpanzees are selfish more often than chance predicts), we also need to consider \(\mathsf{P}(X \le 30)\). The outcome \(x=30\) has the same probability as \(\mathsf{P}(X=60)\) under the null hypothesis and outcomes from 0 to 29 are even less probable. So, the p-value is \(\mathsf{P}(X \le 30) + \mathsf{P}( X \ge 60) \doteq 0.0021\).

In our proof by contradiction analogy, our p-value calculation has not led to an impossibility, but to an improbability. The analysis does not prove \(p \neq 0.5\), but it provides evidence that this is the case. Given the data \(x=60\) which is in the right tail, we have evidence that \(p>0.5\).

Interpret:

There is strong evidence that this chimpanzee makes the prosocial choice more than half the time in the experimental setting (\(p = 0.0021\), two-sided binomial test).

22.2 Statistical Significance

In a formal statistical hypothesis test, many people often use the phrase statistically significant to indicate a p-value which is less than 0.05 or highly statistical significant if the p-value is less than 0.01. This language is ubiquitous. A phrase I prefer (which I acknowledge Professor Jeff Witmer of Oberlin college for coining) is the term statistically discernible), which better defines the appropriate interpretation. In our example, there is a statistically discernible difference between 0.5 and the actual probability that the chimpanzee makes the prosocial choice. Is this difference significant? That depends on the context and ones understanding of the background. I do not know much about chimpanzee behavior, but this data was part of a paper published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences because it was the first (or one of the first) papers that was able to demonstrate that chimpanzees do behave in a prosocial manner, a behavior we recognize as being common among humans. Scientists of animal behavior found this result to of scientific significance.

22.3 Connections to Confidence Intervals

With the same data, we found with 95% confidence the interval \(0.56 < p < 0.76\). Notice that 0.5, the value of \(p\) we used for the hypothesis test, did not fall into this interval. Another way to think about a 95% confidence interval for \(p\) is that it contains those null values for which the two-sided hypothesis test would have a p-value larger than 0.05, while values outside of the interval would have p-values less than 0.05. This observation is consistent with the p-value being less than 0.05 as 0.5 is outside of the interval. (There is not an exact correspondence here due to the discreteness of the binomial distribution, but the observation will hold for any values not too close to the boundary.)

22.4 Other Hypothesis Tests

There are multiple other examples we might consider for statistical hypothesis tests, but all will follow a similar pattern of steps. With the chimpanzee data, we consider several other examples.

22.4.1 Comparsions Between with and without a Partner

Chimpanzee A made the prosocial choice 60 out of 90 times with a partner present, but only 16 out of 30 times without a partner present. Suppose we wanted examine this evidence to test a difference between the probabilities of making the prosocial choice when a partner is present or not.

Here is a statistical model for the data, making binomial assumptions.

\(X_1 \sim \text{Binomial}(n_1,p_1)\)

\(X_2 \sim \text{Binomial}(n_2,p_2)\)

where \(p_1\) and \(p_2\) are the prosocial choice probabilities of Chimpanzee A when a partner is present and when one is not. The observed data is \(x_1 = 60\), \(n_1 = 90\), \(x_2 = 16\), and \(n_2 = 30\).

The hypotheses are:

\(H_0:\, p_1 = p_2\)

\(H_A:\, p_1 \neq p_2\)

Note the difference with the previous test. Here, the null hypothesis states that two parameters are equal, but does not specify the value that they equal. Also, a simple comparison between \(X_1\) and \(X_2\) as we expect each to be near the respective distribution means, but these means are not the same even when the null hypothesis is true because of the different sample sizes. A natural test statistic is the difference in sample proportions: \(\hat{p}_1 = x_1/n_1 = 60/90 \doteq 0.667\) and \(\hat{p}_2 = x_2/n_2 = 16/30 \doteq 0.533\). The difference for the observed data is 0.133 (rounded to three decimal places after taking the difference). Does this data provide evidence of a difference between \(p_1\) and \(p_2\), the long-run prosocial probabilities with and without a partner for this chimpanzee?

Here is a situation where a direct binomial calculation will not suffice. We will examine three different approaches to calculate a p-value: simulation, the normal approximation, and likelihood. In each case we are addressing the question, how unusual is the value of the test statistic, 0.133, when the null hypothesis is true?

22.4.2 Simulation Approach

Here, the idea is to simulate the sampling distribution of the test statistic and determine the p-value based on the simulated values. As a p-value is the probability when the null hypothesis is true, we need to simulate data assuming that \(p_1 = p_2\). The null hypothesis does not specify a value, but it is adequate to use the estimated data to estimate it. The idea is that the simulated test statistic distribution should be a good approximation if we use a value for \(p_1\) and \(p_2\) which is close to their true shared value. Under the null hypothesis, \(X_1\) and \(X_2\) have the distribution of the number of heads in coin tosses using coins with the same head probability, so their sum is binomial also. The combined-data estimate of \(p\) is \(\hat{p} = (60+16) / (90 + 30) = 76/120 \doteq 0.633\). We will use this value for both \(p_1\) and \(p_2\) in the simulation.

In the simulation,

we will use rbinom() to generate random values for \(X_1\) and \(X_2\) for some large number of replications,

calculate the test statistic for each,

and summarize this sampling distribution.

The following R code does the calculations.

# A tibble: 2 × 3

x n p

<dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

1 60 90 0.667

2 16 30 0.533# A tibble: 1 × 2

p_0 stat

<dbl> <dbl>

1 0.633 0.133## P-value simulation

B = 100000

dat = tibble(

x1 = rbinom(B, chimpA$n[1], chimpA_sum$p_0),

x2 = rbinom(B, chimpA$n[2], chimpA_sum$p_0),

p1 = x1/chimpA$n[1],

p2 = x2/chimpA$n[2],

diff = p1 - p2)

head(dat)# A tibble: 6 × 5

x1 x2 p1 p2 diff

<int> <int> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

1 63 21 0.7 0.7 0

2 58 18 0.644 0.6 0.0444

3 59 17 0.656 0.567 0.0889

4 57 19 0.633 0.633 0

5 53 25 0.589 0.833 -0.244

6 59 15 0.656 0.5 0.156 # A tibble: 1 × 2

mean sd

<dbl> <dbl>

1 0.0000160 0.102Notice that the mean is very close to 0. We expected this as each sample proportion should be close to its population mean and these means are identical in the simulation. The standard deviation of the sampling distribution is about 0.1. That implies that a typical difference between the sample means is about 0.1.

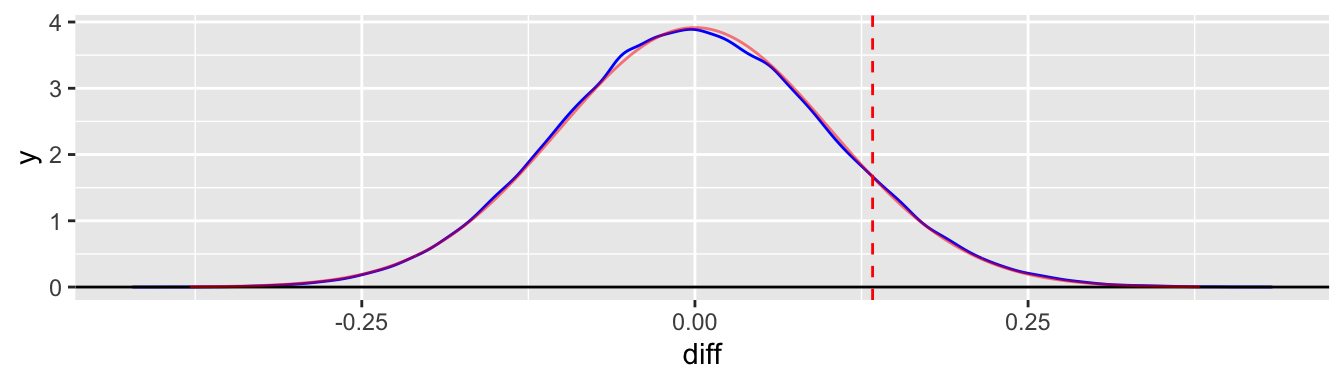

We can also graph this distribution and indicate where the observed test statistic lies. We superimpose a normal density with a mean of zero and the same standard deviation in a faded red color for comparison.

ggplot(dat, aes(x = diff)) +

geom_density(color = "blue") +

geom_hline(yintercept = 0) +

geom_vline(xintercept = chimpA_sum$stat, color = "red", linetype = "dashed") +

geom_norm_density(mu = 0, sigma = dat_sum$sd, color = "red", alpha = 0.5)

Notice that the observed difference, 0.133, is just slightly larger than the standard deviation, 0.1. In fact, the \(z\)-score for this difference is (using the simulated values)

[1] 1.308762We can calculate a p-value simply by counting the proportion of simulated values at least as large, in absolute value, as the observed test statistic.

## direct p-value calculation

tol = 1e-8 ## a small positive number to avoid comparing equality

pval_1 = dat %>%

summarize(pval = mean( (abs(diff) > chimpA_sum$stat - tol) )) %>%

pull(pval)

pval_1[1] 0.21076Taking advantage of the appranent excellent approximation between the simulated samplng distribution and the normal density, we could also have found the area under the normal curve.

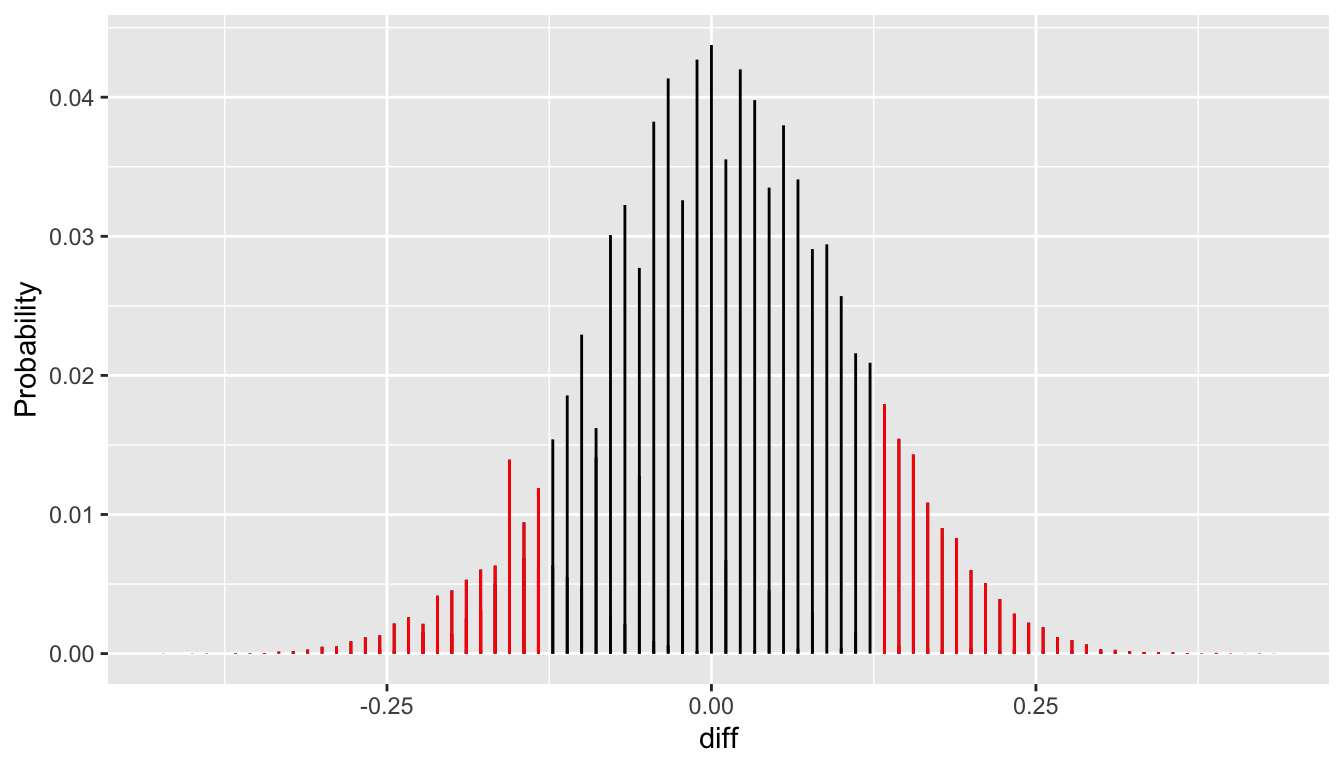

[1] 0.1906149The p-values are not identical, but each is about one in five. This is because the graphed density conceals the discreteness in the actual simulated sampling distribution. This graph has a line segment at each realized sample difference with height proportional to it relative frequency. The p-value is the sum of the heights of the red line segments.

dat2 = dat %>%

count(diff) %>%

mutate(y = n / sum(n))

ggplot(dat2, aes(x = diff, y = y,

xend = diff, yend = 0)) +

geom_segment() +

geom_segment(data = filter(dat2, abs(diff) >= chimpA_sum$stat),

color = "red") +

ylab("Probability")

22.4.3 Z-Test

Another approach avoids simulation and uses the fact that we can use theory to say what the simulated standard error is.

\[ \mathsf{SE}(\hat{p}_1 - \hat{p}_2) = \sqrt{ \frac{p_1(1-p_1)}{n_1} + \frac{p_2(1-p_2)}{n_2}} \]

The plug-in estimate using \(\hat{p}_1\) and \(\hat{p}_2\) is what we use. (For hypothesis testing, we do not use the Agresti-Coull modification.)

# A tibble: 2 × 3

x n p

<dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

1 60 90 0.667

2 16 30 0.533[1] 0.1037566[1] 1.285059[1] 0.1987717This p-value is nearly the same as the previous ones.

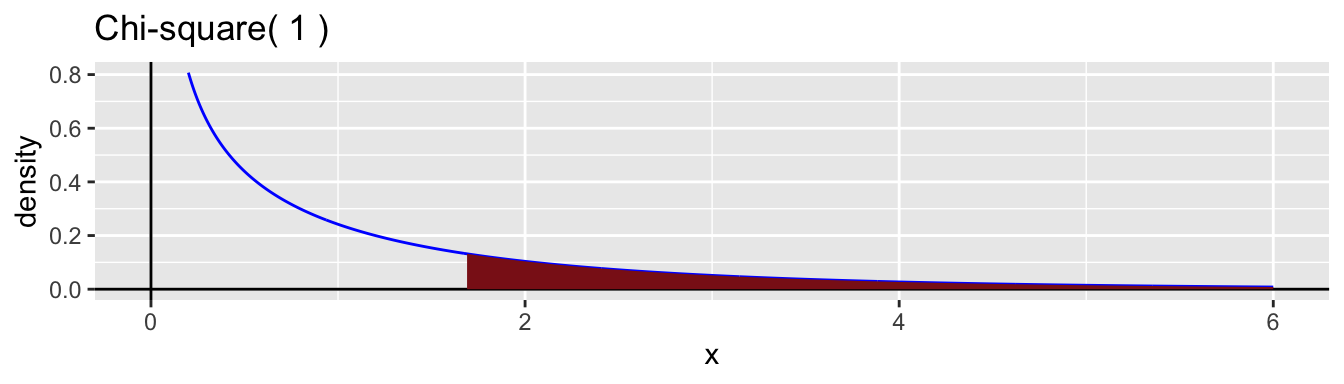

22.4.4 Likelihood Ratio Test

Finally, we examine a likelihood ratio test approach. We examined likelihood earlier. In a hypothesis testing setting, we estimate the parameters that maximize the likelihood for both the restricted null hypothesis and the more general alternative hypothesis. We calculate the likelihood ratio test statistic, \[ G = 2 \ln(\hat{L}_1 - \hat{L}_0) \] where \(\hat{L}_0\) is the likelihood of the data maximized under the null hypothesis and \(\hat{L}_1\) is the likelihood maximized under the alternative hypothesis. Theory says that this statistic has a chi-square distribution with degrees of freedom equal to the difference in the number of parameters.

The null hypothesis has a single estimated parameter

\[ \hat{p}_1 = \hat{p}_2 = \frac{60+16}{90+30} \doteq 0.633 \]

The alternative hypothesis has two parameters as the probabilities are allowed to be different: \(\hat{p}_1 = 60/90 \doteq 0.667\) and \(\hat{p}_2 = 16/30 \doteq 0.533\).

The difference in the number of degrees of freedom is \(2-1 = 1\). So, the approximate sampling distribution of \(G\) when the null hypothesis is true chi-square with 1 degree of freedom.

The following R code calculates both log-likelihood values and the test statistic.

chimpA = chimpA %>%

mutate(p_0 = sum(x)/sum(n),

logl_0 = dbinom(x, n, p_0, log = TRUE),

logl_1 = dbinom(x, n, p, log = TRUE))

chimpA# A tibble: 2 × 6

x n p p_0 logl_0 logl_1

<dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

1 60 90 0.667 0.633 -2.64 -2.42

2 16 30 0.533 0.633 -2.56 -1.93chimpA_logl = chimpA %>%

summarize(logl_0 = sum(logl_0),

logl_1 = sum(logl_1),

G = 2*(logl_1 - logl_0),

pval = 1 - pchisq(G,1))

chimpA_logl# A tibble: 1 × 4

logl_0 logl_1 G pval

<dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

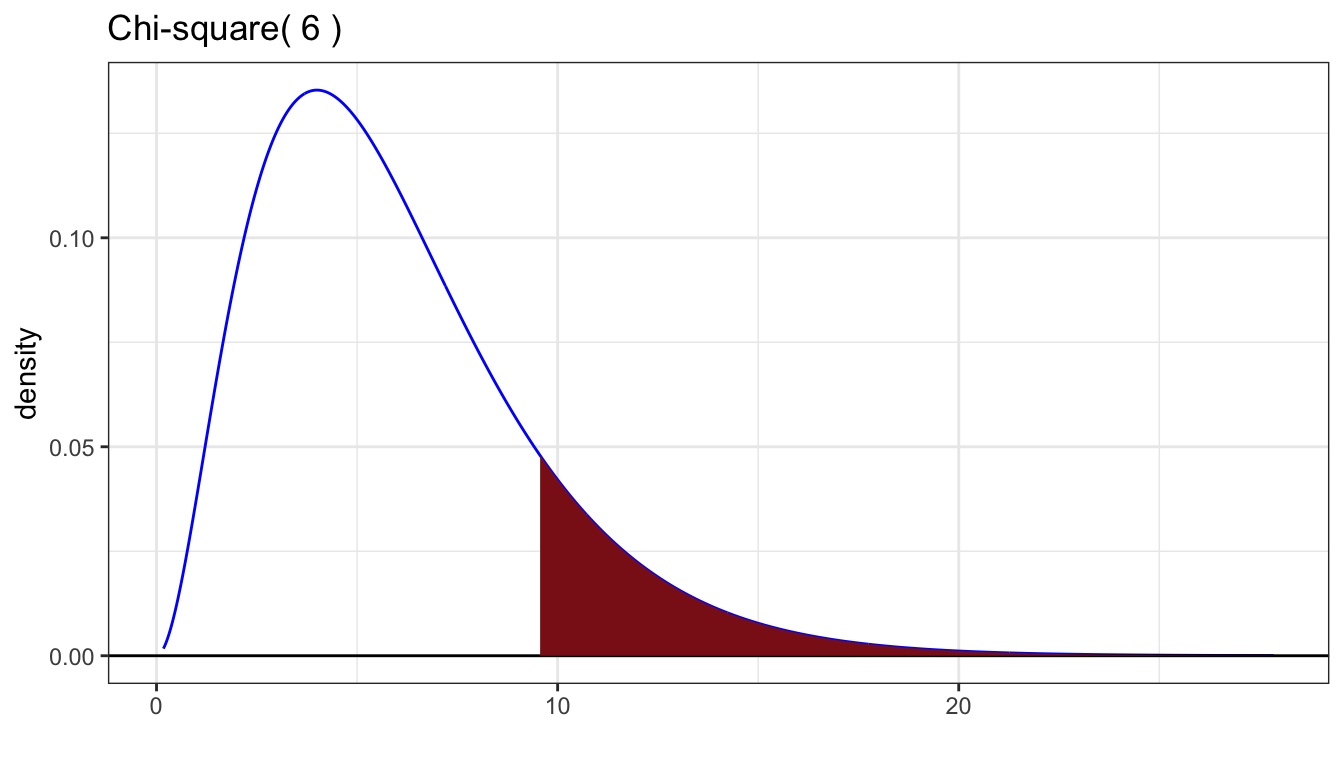

1 -5.20 -4.35 1.69 0.194Here is a graph of the chi-square distribution to illustrate the value of the p-value.

22.4.5 Interpretation

Regardless how the p-value is calculated, the interpretation is the same.

The data is consistent with there being no difference in the probabilities that Chimpanzee A makes the prosocial choices with and without a partner (\(p = 0.2\)).

Note that this data does not contain strong evidence that these probabilities are equal. There is simply a lack of evidence that they are different. The main factor is that with only 30 trials without a partner, there is a lot of uncertainty in the value of this probability and many of the plausible values are also plausible for the probability with a partner. The authors of the study combined the data from all chimpanzees to demonstrate the point they wished to make by increasing the sample sizes for both groups. This analysis requires the assumption that the chimpanzees all have the same prosocial probability when there is a partner. We examine this next.

22.5 Comparing Multiple Probabilities

A model for the seven chimpanzees is that they each have their own prosocial choice probability.

\[ X_i \sim \text{Binomial}(n_i, p_i) \text{ for $i=1,\ldots,7$} \]

Here is a summary of the data for each partner.

| actor | n | prosocial | selfish | phat |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 90 | 60 | 30 | 0.667 |

| B | 90 | 60 | 30 | 0.667 |

| C | 90 | 57 | 33 | 0.633 |

| D | 90 | 50 | 40 | 0.556 |

| E | 90 | 48 | 42 | 0.533 |

| F | 90 | 47 | 43 | 0.522 |

| G | 70 | 37 | 33 | 0.529 |

The overall prosocial rate is \(359/610 = 0.589\).

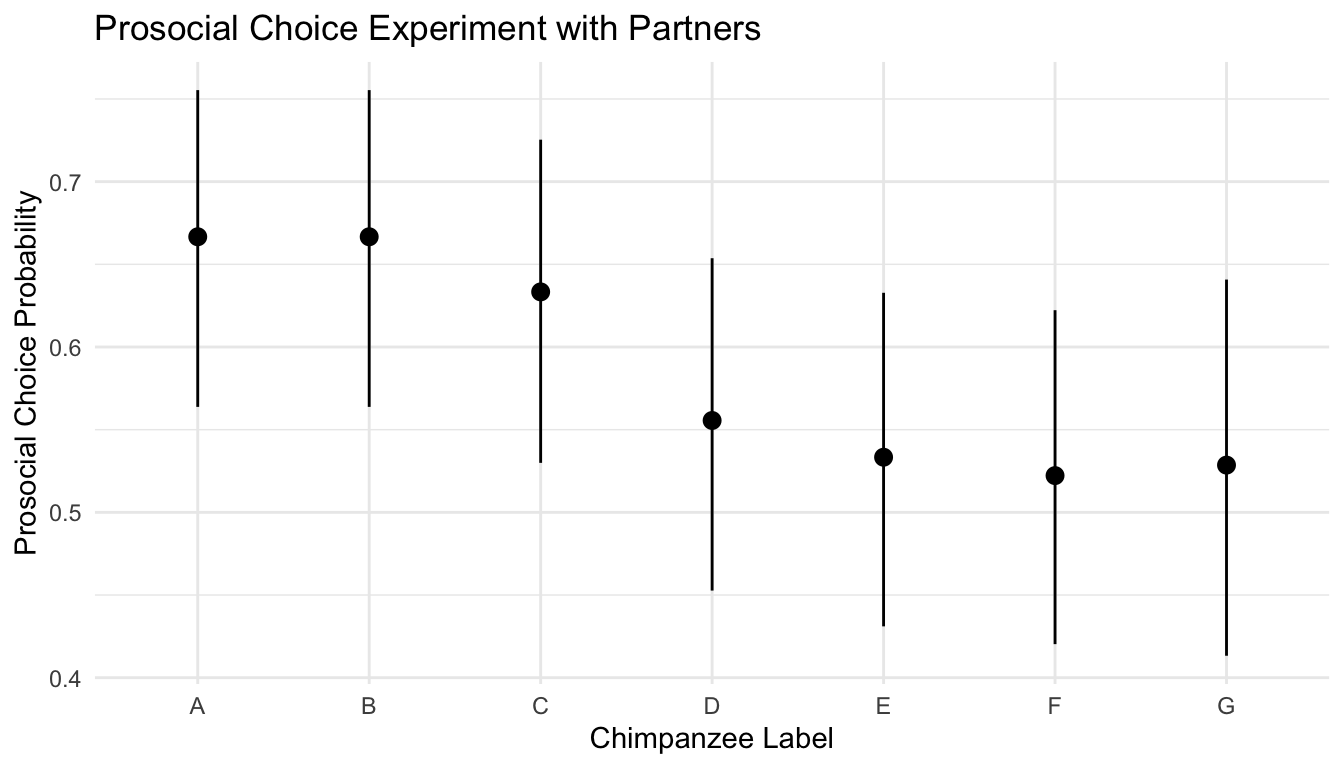

ggplot(chimps1) +

geom_pointrange(aes(x = actor, y = phat, ymin = ci_a, ymax = ci_b)) +

xlab("Chimpanzee Label") +

ylab("Prosocial Choice Probability") +

ggtitle("Prosocial Choice Experiment with Partners") +

theme_minimal()

Figure 22.1: Maximum Likelihood Estimates and Agresti-Coull 95% Confidence Intervals

The question we wish to address with a hypotheses test is: Does each chimpanzee has the same probability of making the prosocial choice good fit to the data? Or, is there evidence in the data that the chimpanzees behave individually?

22.6 Likelihood Ratio Test

We can evaluate these two hypotheses by comparing the likelihoods. The restricted (null) model says that all of the chimpanzees have the same prosocial probability \(p\). Under this model, there is only a single parameter \(p\) to estimate and this estimate is \(\hat{p} = 359/610 \doteq 0.589\). The more general model has separate estimates of \(\hat{p}_i\) for each chimpanzee.

\[ H_0: p_1 = \ldots = p_7 \\ H_a: \text{not}~ p_1 = \ldots = p_7 \]

The null hypothesis is that all of the prosocial probabilities are the same. The alternative hypothesis is that they are not all the same (at least one is different).

If \(L_0\) is the maximum likelihood of the data under the null hypothesis and \(L_1\) is the maximum likelihood of the data under the alternative hypothesis, the likelihood ratio is \(R = L_0/L_1\). As likelihoods might be very small, we often take the natural log of this ratio. Furthermore, we often multiply the log by \(-2\) because theory says that this statistic can be compared to a chi-square distribution for large enough samples (and some other conditions).

22.6.1 Calculation of the LRT Statistic

Instead of calculating \(R\), we calculate instead \(G = -2\ln R\). This is \(G = -2 (\ln L_0 - \ln L_1) = 2(\ln L_1 - \ln L_0)\). So, we seek twice the difference in log-likelihoods. The log-likelihood under the null hypothesis is just the sum of the logs of the binomial probabilities of obtaining the individual success counts when all \(p_i\) are estimated to be \(359/610\). The log-likelihood under the alternative hypothesis is the sum of the log-likelihoods for each of the seven different binomial probabilities, each with its own estimate of \(p\).

We can use the log argument to dbinom() to return the log of the probability instead of the probability itself.

Use dplyr code to do the calculations.

dat = chimps1 %>%

mutate(p_0 = sum(prosocial)/sum(n)) %>%

mutate(log_L0 = dbinom(prosocial,n,p_0,log=TRUE),

log_L1 = dbinom(prosocial,n,phat,log=TRUE))

lrt = dat %>%

summarize(log_L0 = sum(log_L0),

log_L1 = sum(log_L1),

lrt = 2*(log_L1 - log_L0),

R = exp(log_L0-log_L1))

lrt# A tibble: 1 × 4

log_L0 log_L1 lrt R

<dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

1 -21.8 -17.1 9.56 0.0083822.6.2 Chi-square approach to the p-value

Theory says that if the sample sizes are large enough, then the sampling distribution of the LRT statistic has an approximate chi-square distribution with degrees of freedom equal to the difference in the number of free parameters between the two hypotheses. Here the null hypothesis has 1 free parameter to estimate. The alternative hypothesis has 7. So, we want to compare to a chi-square distribution with 6 degrees of freedom. This is the distribution you would get by taking 6 independent standard normal random variables, squaring them, and summing up the squared values. The mean is the number of degrees of freedom, here 6. The standard deviation is the square root of twice the degrees of freedom, or here \(\sqrt{12} \doteq 3.46\). The p-value is always the area to the right, as when the statistic is larger, the likelihood under the alternative model is even higher than the null, lending more evidence against the null hypothesis in favor of the alternative hypothesis.

# A tibble: 1 × 5

log_L0 log_L1 lrt R p_value

<dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

1 -21.8 -17.1 9.56 0.00838 0.144The p-value is not significant at the 5% level (the p-value is larger than 0.05). We would expect a result at least this extreme about once every 7 experiments. If I guessed the day of the week you were born and I got it right, would you be surprised? A little bit, but a 1 in 7 chance is not that unusual.

Here is an interpretation of the results of this test.

The observed data is consistent with all seven chimpanzees having the same probability of making the prosocial choice when there is a partner (\(p=0.144\), \(G = 9.56\), likelihood ratio test).