1.3 Polar form in the Euclidean plane

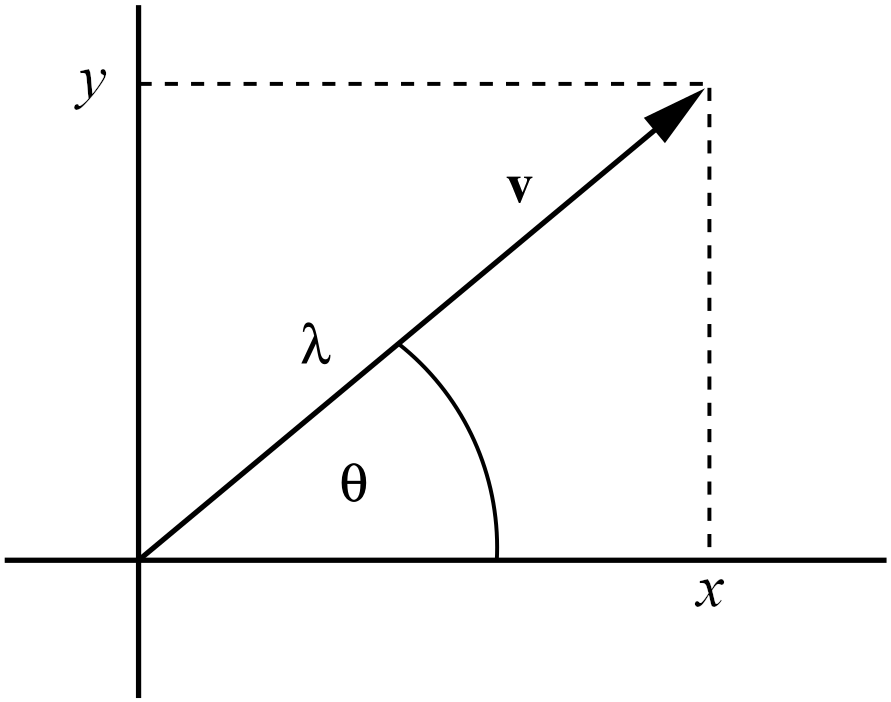

In this section we will focus on vectors in \(\mathbb{R}^2\), and consider a different way of representing them. As well as defining a vector in \(\mathbb{R}^2\) based on its components in the \(x\) and \(y\) directions, we could also define it based on its length and its angle from the \(x\)-axis. This is known as polar form, and is illustrated in Figure 1.4.

Figure 1.4: A vector \(v\) in \(\mathbb{R}^2\) represented by Cartesian coordinates \((x,y)\) or by polar coordinates \(\lambda, \theta\). We have \(x=\lambda\cos\theta\), \(y=\lambda \sin\theta\), \(\lambda=\sqrt{x^2+y^2}\) and \(\tan\theta=\dfrac{y}{x}\).

In particular, a unit vector has length one, hence all unit vectors lie on the circle of radius one in \(\mathbb{R}^2\), and a unit vector is determined solely by its angle \(\theta\) with the \(x\)-axis. By elementary geometry we find that the unit vector with angle \(\theta\) to the \(x\)-axis is given by \[\label{eq:unitvec} u(\theta):=\begin{pmatrix}\cos\theta\\ \sin\theta\end{pmatrix}.\]

We can then multiply by a scalar order to obtain any vector in \(\mathbb{R}^2\), and this gives us a unique vector. In particular, the scalar that we multiply our unit vector by is the norm of the vector.

For every \(v\in\mathbb{R}^2\), \(v\neq 0\), there exist unique \(\theta\in [0,2\pi)\) and \(\lambda\in (0,\infty)\) with \[v=\lambda u(\theta)\]

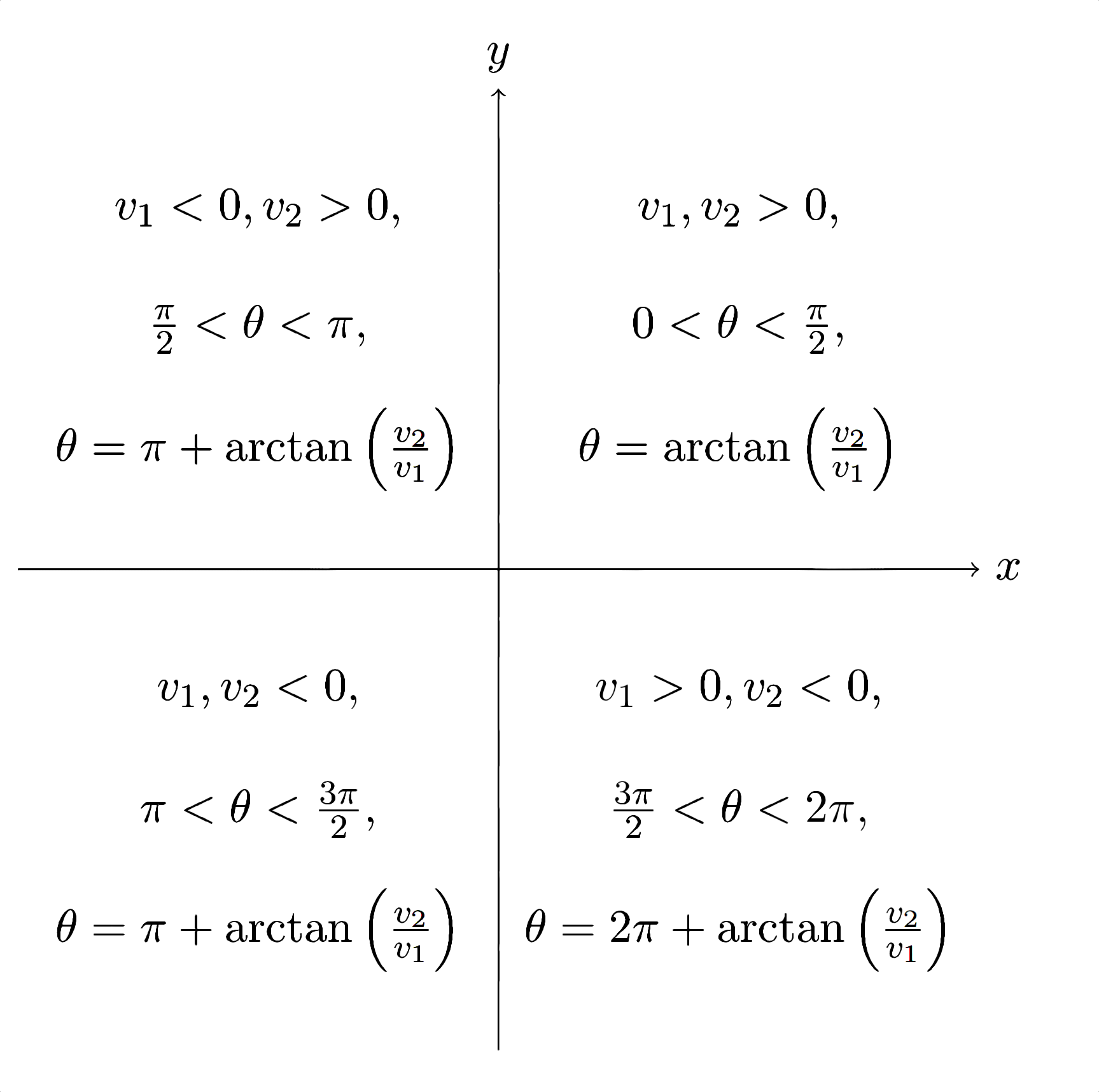

Given \(v=\begin{pmatrix}v_1\\ v_2\end{pmatrix}\neq 0\) we have to find \(\lambda>0\) and \(\theta\in [0,2\pi)\) such that \[\begin{pmatrix}v_1\\ v_2\end{pmatrix}=\lambda u(\theta)=\begin{pmatrix}\lambda \cos \theta\\ \lambda \sin\theta\end{pmatrix}.\] Since \(\lVert\lambda u(\theta)\rVert=\lambda\lVert u(\theta)\rVert=\lambda\) (note that \(\lambda>0\), hence \(\lvert\lambda\rvert=\lambda\)) we get immediately \[\lambda=\lVert v\rVert.\] To determine \(\theta\) we have to solve the two equations \[\cos\theta=\frac{v_1}{\lVert v\rVert} ,\quad \sin\theta=\frac{v_2}{\lVert v\rVert} ,\] which is in principle easy, but we have to be a bit careful with the signs of \(v_1,v_2\). If \(v_2>0\) we can divide the first by the second equation and obtain \(\cos\theta/\sin\theta=v_1/v_2\), hence \(\theta=\cot^{-1} \frac{v_1}{v_2},\) that is \[\theta=\arctan\frac{v_2}{v_1}\in (0,\pi) .\] If \(v_1>0\) and \(v_2 < 0\) we have \(\arctan (v_2/v_1) \in (-\frac{\pi}{2},0)\) and so \(\theta=2\pi+\arctan (v_2/v_1)\); analogous arguments apply in the remaining cases and this is illustrated in Figure 1.5.

□

Figure 1.5: How to calculate the argument for \((v_1,v_2)\) in each quadrant of the Euclidean plane.

The converse of this result also holds, that is given \(\theta\in [0,2\pi)\) and \(\lambda\geq 0\) we get a unique vector with direction \(\theta\) and length \(\lambda\): \[v=\lambda u(\theta)=\begin{pmatrix}\lambda\cos\theta\\ \lambda\sin\theta\end{pmatrix}.\]

There are many practical situations where the polar form of a vector might be more useful than the Cartesian form, for example a ship navigating from a port may travel a certain distance at a given angle. In the next chapter, we will look at an extended example of vectors in \(\mathbb{R}^2\), namely the complex plane, see how complex numbers can be viewed as vectors and how their polar form provides a useful insight into the geometric interpretation of multiplication.