Chapter 5 Basic Webscraping

5.1 The rvest package

5.1.2 Read the URL

## [1] "xml_document" "xml_node"## {html_document}

## <html xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1999/xhtml" xmlns:og="http://ogp.me/ns#" lang="en-US">

## [1] <head>\n<meta http-equiv="Content-Type" content="text/html; charset=UTF-8 ...

## [2] <body data-rsssl="1" class="archive category category-articles category-5 ...## {xml_nodeset (5)}

## [1] <a href="https://www.e-ir.info/2022/01/19/opinion-the-libyan-border-as-a- ...

## [2] <a href="https://www.e-ir.info/2022/01/17/opinion-putins-obsession-with-u ...

## [3] <a href="https://www.e-ir.info/2022/01/14/opinion-kazakhstans-dark-herita ...

## [4] <a href="https://www.e-ir.info/2022/01/13/legitimacy-and-nationalism-chin ...

## [5] <a href="https://www.e-ir.info/2022/01/09/business-and-human-rights-overc ...## [1] "https://www.e-ir.info/2022/01/19/opinion-the-libyan-border-as-a-testing-ground-for-european-sovereignty/"

## [2] "https://www.e-ir.info/2022/01/17/opinion-putins-obsession-with-ukraine-as-a-russian-land/"

## [3] "https://www.e-ir.info/2022/01/14/opinion-kazakhstans-dark-heritage/"

## [4] "https://www.e-ir.info/2022/01/13/legitimacy-and-nationalism-chinas-motivations-and-the-dangers-of-assumptions/"

## [5] "https://www.e-ir.info/2022/01/09/business-and-human-rights-overcoming-old-paradigms-pushing-for-new-frontiers/"df$title <- page %>%

html_nodes(".heading a") %>%

html_attr("title")

df$authors <- page %>%

html_nodes(".h--meta a") %>%

html_text()Can you get the date?1

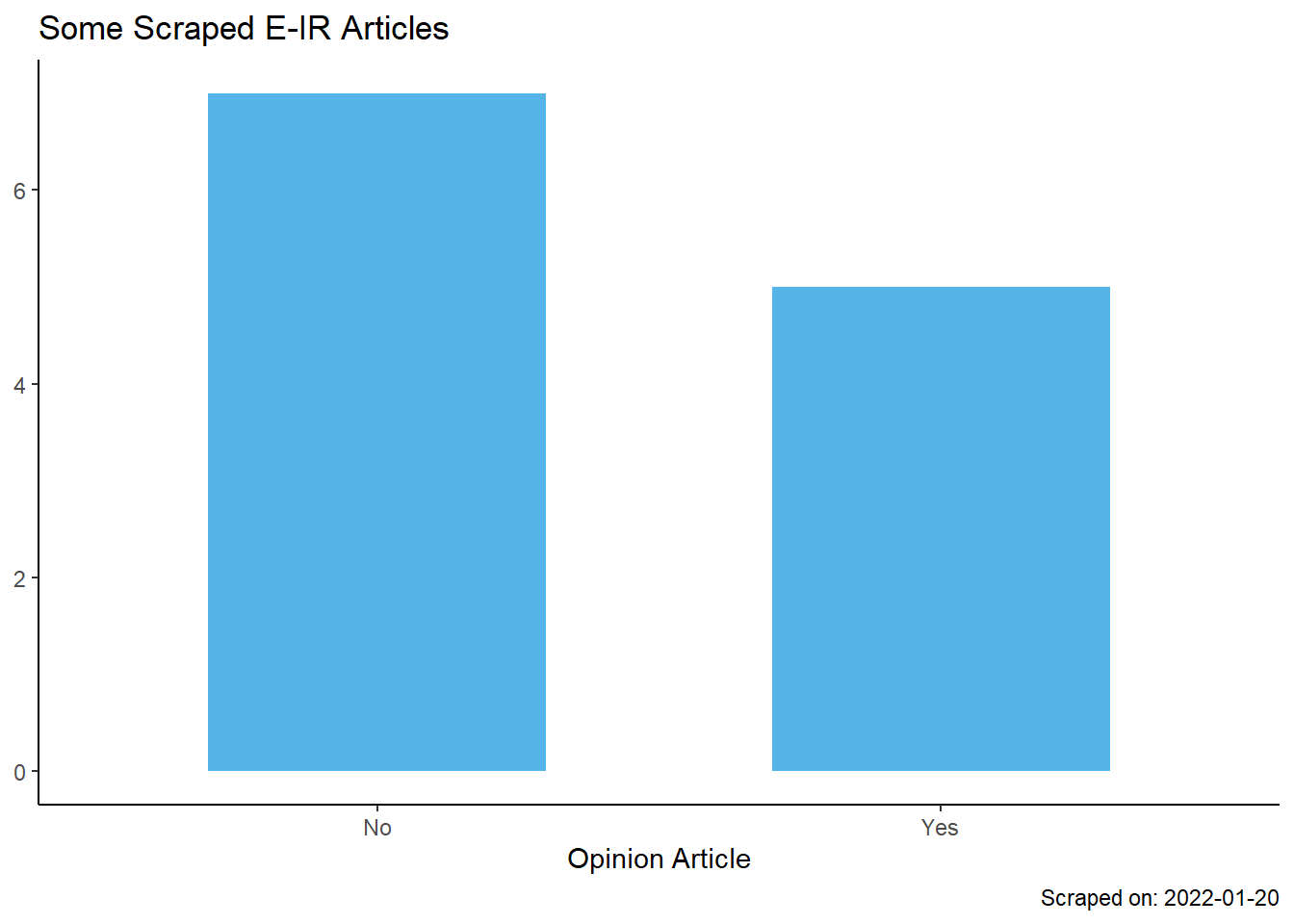

5.1.3 Ploting

df %>%

ggplot()+

geom_bar(aes(as.factor(opinion)),

fill="#56B4E9",

width = .6)+

scale_x_discrete(labels = c("No","Yes"))+

scale_y_continuous(breaks= scales::pretty_breaks())+

labs(x = "Opinion Article",

y = NULL,

title = "Some Scraped E-IR Articles",

caption = sprintf("Scraped on: %s", Sys.Date())

)+

theme_classic()

5.2 Cleaning Text

## [1] "https://www.e-ir.info/2022/01/19/opinion-the-libyan-border-as-a-testing-ground-for-european-sovereignty/"## [1] "Opinion – The Libyan Border as a Testing Ground for European Sovereignty\n\n \n \n \n Robert Palmer \n \n\n \n Download PDF\n \n Jan 19 2022\n • \r\n\t\t\t\t\r\n\t\t\t\t\r\n\t\t\t\t0\r\n\t\t\t views\n \n \n \n \n\n \n \n \n\n \n \n Nicolas Economou/Shutterstock\n \n \n \n \n \n \nMigrants and asylum seekers use the Central Mediterranean route to enter the EU out with regulated processes. The journey is dangerous, requiring a departure from North Africa across the Mediterranean Sea to reach Europe’s shores. Since the fall of Gaddafi in 2011, Libya has become one of the main gateways for illegal migration to Europe. The EU aims to lock the North African nation down as a transit point by deploying a border assistance mission. Immediately, this tactic is a means of tackling problematic immigration beyond Europe’s borders. But it is also an opportunity – to be won or lost – that could play a crucial role in defining and asserting the bloc’s as-of-yet-undetermined stance on ‘sovereignty’.\n\n\n\nWith so many migrants travelling through Libya, smuggling and trafficking networks there have erupted. Those on the ground claim the country has become a nexus of coercion, torture, and deprivation. The instability unleashed by the Libyan civil war has dragged roughly 650,000 migrants into dire conditions. Those living in the Libya-based migrant community are reportedly “vulnerable to extortion, violence, and slave-like work conditions,” while migrants held in detention centres there “may experience overcrowding, sexual abuse, forced labour, torture, and deprivation of food, sunlight, and water.”\n\n\n\nPressure on the EU is mounting. On the one hand, there are the practical considerations — a collection of nations struggling with the flow of people simply trying to escape horrifying circumstances. On the other hand, there is the challenge of dealing with the problem in a humane and distinctively European way: this last part, in fact, might create the greater trouble for lawmakers.\n\n\n\nA United Nations report states that, in all likelihood, the lack of human rights protection for migrants at sea, \n\n\n\nis not a tragic anomaly, but rather a consequence of concrete policy decisions and practices by the Libyan authorities, the European Union Member States and institutions, and other actors.\n\n\n\nTo its credit, the EU has made clear that it plans to improve the situation. While this move is a vital one, it is also a crucial moment for a nascent idea of European sovereignty. The situation unfolds in a dynamic context under the shadow of a crescent China and a waning, less-than dependable ally in the United States. PGRpdiBjbGFzcz0iYWR2YWRzLWluZmVlZC0xLWRlc2t0b3AiIHN0eWxlPSJtYXJnaW4tYm90dG9tOiAyNHB4OyAiIGlkPSJhZHZhZHMtMzYxODg1OTciPjxzY3JpcHQgYXN5bmMgc3JjPSIvL3BhZ2VhZDIuZ29vZ2xlc3luZGljYXRpb24uY29tL3BhZ2VhZC9qcy9hZHNieWdvb2dsZS5qcz9jbGllbnQ9Y2EtcHViLTY4MjcxMDY3NjQwNDI3MzUiIGNyb3Nzb3JpZ2luPSJhbm9ueW1vdXMiPjwvc2NyaXB0PjxpbnMgY2xhc3M9ImFkc2J5Z29vZ2xlIiBzdHlsZT0iZGlzcGxheTpibG9jazsiIGRhdGEtYWQtY2xpZW50PSJjYS1wdWItNjgyNzEwNjc2NDA0MjczNSIgCmRhdGEtYWQtc2xvdD0iIiAKZGF0YS1hZC1mb3JtYXQ9ImF1dG8iPjwvaW5zPgo8c2NyaXB0PiAKKGFkc2J5Z29vZ2xlID0gd2luZG93LmFkc2J5Z29vZ2xlIHx8IFtdKS5wdXNoKHt9KTsgCjwvc2NyaXB0Pgo8L2Rpdj4=A European Commission action plan states that:\n\n\n\nThe Commission intends to step up border management support at Libya’s Southern border, while in parallel strengthening cross-border cooperation between Libya and its bordering countries in the South, including Niger.\n\n\n\nIncreasingly, voices in the EU call for either a greater level of integration than ever before, or a move in the opposite direction, towards disparate nationalism. Brexit, for its part, has demonstrated that even if presented as greener pastures, the going-it-alone strategy is a risky one at best.\n\n\n\nThe German chancellor, Olaf Scholtz, for his part has indicated an interest in pursuing a German vision of European sovereignty – but it is one that appears to diverge from equivalent notions in France. Though Emanuel Macron may lead the charge on a more militant, assertive vision of Europe, he faces a presidential election in April 2022. While France might hold the 6-month rotating stewardship of the EU, there are no guarantees that French centrist political ambitions will live to see it through.\n\n\n\nThe necessity of a response to the encroachment of Russia on the eastern flank, adds a certain preparatory atmosphere. In this sense, the migrant conundrum offers a formative testing ground for defining and assessing practicalities around sovereignty. But, as with many such crises, the adequacy of the means employed must support the scale of ambitions. And indeed, many believe that it is only the bloc’s united size that will allow it to remain relevant and active on the global stage. “The choice is not between national and European sovereignty,” wrote Jean Pisani-Ferry, a former advisor to Macron, back in December 2019. “It is between European sovereignty and none at all.”\n\n\n\nFor all of these reasons, the Libyan border situation is one that calls for caution. With European sovereignty far from set, any reliance on foreign contractors to bolster security could quickly become problematic. For instance, were the EU to assign projects to companies governed by foreign powers, this could inadvertently, both symbolically and strategically, cede sovereignty to foreign masters. Given the increasing sense of a free-for-all in the realm of private military contractors, confidence is in decline. That is why outsourcing to non-member states could get even more complicated.\n\n\n\nA European Parliament resolution warned that “no local PSC [private security company] should be employed or subcontracted in conflict regions” and that the EU should favour companies “genuinely based in Europe” and subjected to EU law. However, this resolution has limited scope and is non-binding, therefore its “impact in the theatre remains unclear”.\n\n\n\nThe EU has already had some unfortunate episodes which highlighted the issue of handing out contracts to foreign companies, either local entities or non-European ones working abroad. One noteworthy example was the use of the Canadian firm GardaWorld and British firm G4S in places like Afghanistan. Even though Gardaworld was partnering with the French security company Amarante, Gardaworld always kept leadership in field operations. As a result, the companies’ complete inability to support and evacuate their security personnel during the Kabul Airlift even made headlines last year. The ambiguous role private companies are taking in modern conflicts underlines the need for the EU to work with companies bound by EU law.\n\n\n\nFollowing the 2015 migrant crisis, consensus on EU immigration policy took a bruising. And even now, any future definition remains in flux – much like the European project as a whole.Such considerations give an indication of the subtle forces at play in the skirmish for European sovereignty. It remains to be seen what course officials plot on the already incendiary Libyan border.\nFurther Reading on E-International RelationsThe European Union Immigration Agreement with Libya: Out of Sight, Out of Mind?\n\nThe EU-Libya Migrant Deal: A Deal of Convenience\n\nAssessing the Responsibility of EU Officials for Crimes Against Migrants in Libya\n\nFortress Europe? Porous Borders and EU Dependence on Neighbour Countries\n\nOpinion – A New Pact on Migration and Asylum in Europe\n\nEuropean Union Readmission Agreements: Deportation as a Gateway to Displacement?\nPGRpdiBjbGFzcz0iYWR2YWRzLWhlYWRsaW5lIiBzdHlsZT0ibWFyZ2luLWxlZnQ6IGF1dG87IG1hcmdpbi1yaWdodDogYXV0bzsgdGV4dC1hbGlnbjogY2VudGVyOyBtYXJnaW4tYm90dG9tOiAyMnB4OyAiIGlkPSJhZHZhZHMtMzQwMDU3Njg5Ij48c2NyaXB0IGFzeW5jIHNyYz0iLy9wYWdlYWQyLmdvb2dsZXN5bmRpY2F0aW9uLmNvbS9wYWdlYWQvanMvYWRzYnlnb29nbGUuanM/Y2xpZW50PWNhLXB1Yi02ODI3MTA2NzY0MDQyNzM1IiBjcm9zc29yaWdpbj0iYW5vbnltb3VzIj48L3NjcmlwdD48aW5zIGNsYXNzPSJhZHNieWdvb2dsZSIgc3R5bGU9ImRpc3BsYXk6aW5saW5lLWJsb2NrO3dpZHRoOjcyOHB4O2hlaWdodDo5MHB4OyIgCmRhdGEtYWQtY2xpZW50PSJjYS1wdWItNjgyNzEwNjc2NDA0MjczNSIgCmRhdGEtYWQtc2xvdD0iNDcxMDkzMTAwMCI+PC9pbnM+IAo8c2NyaXB0PiAKKGFkc2J5Z29vZ2xlID0gd2luZG93LmFkc2J5Z29vZ2xlIHx8IFtdKS5wdXNoKHt9KTsgCjwvc2NyaXB0Pgo8L2Rpdj48c2NyaXB0Piggd2luZG93LmFkdmFuY2VkX2Fkc19yZWFkeSB8fCBqUXVlcnkoIGRvY3VtZW50ICkucmVhZHkgKS5jYWxsKCBudWxsLCBmdW5jdGlvbigpIHthZHZhZHMubW92ZSgiI2FkdmFkcy0zNDAwNTc2ODkiLCAiaDEiLCB7IG1ldGhvZDogImluc2VydEJlZm9yZSIgfSk7fSk7PC9zY3JpcHQ+\n \n\n \n\n \n \n \n \n \n About The Author(s)\n \n Robert Palmer is a freelance business advisor and defense expert.\n \n \n \n \n \n \n \n TagsEuropean UnionLibyaMigration\n\n \n \n "text <- text %>% str_replace_all("[\r\n]" , " ")

text <- text %>% str_remove("(.*)(Shutterstock|Loading views)")

text <- text %>% str_remove_all("[:graph:]{50,1000}")

text <- text %>% str_remove_all("[:space:]{2,}")

text <- text %>% str_remove_all("(Further Reading|References)(.*)")| url | title | authors | opinion | text |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| https://www.e-ir.info/2022/01/19/opinion-the-libyan-border-as-a-testing-ground-for-european-sovereignty/ | Opinion – The Libyan Border as a Testing Ground for European Sovereignty | Robert Palmer | 1 | Migrants and asylum seekers use the Central Mediterranean route to enter the EU out with regulated processes. The journey is dangerous, requiring a departure from North Africa across the Mediterranean Sea to reach Europe’s shores. Since the fall of Gaddafi in 2011, Libya has become one of the main gateways for illegal migration to Europe. The EU aims to lock the North African nation down as a transit point by deploying a border assistance mission. Immediately, this tactic is a means of tackling problematic immigration beyond Europe’s borders. But it is also an opportunity – to be won or lost – that could play a crucial role in defining and asserting the bloc’s as-of-yet-undetermined stance on ‘sovereignty’.With so many migrants travelling through Libya, smuggling and trafficking networks there have erupted. Those on the ground claim the country has become a nexus of coercion, torture, and deprivation. The instability unleashed by the Libyan civil war has dragged roughly 650,000 migrants into dire conditions. Those living in the Libya-based migrant community are reportedly “vulnerable to extortion, violence, and slave-like work conditions,” while migrants held in detention centres there “may experience overcrowding, sexual abuse, forced labour, torture, and deprivation of food, sunlight, and water.”Pressure on the EU is mounting. On the one hand, there are the practical considerations — a collection of nations struggling with the flow of people simply trying to escape horrifying circumstances. On the other hand, there is the challenge of dealing with the problem in a humane and distinctively European way: this last part, in fact, might create the greater trouble for lawmakers.A United Nations report states that, in all likelihood, the lack of human rights protection for migrants at sea,is not a tragic anomaly, but rather a consequence of concrete policy decisions and practices by the Libyan authorities, the European Union Member States and institutions, and other actors.To its credit, the EU has made clear that it plans to improve the situation. While this move is a vital one, it is also a crucial moment for a nascent idea of European sovereignty. The situation unfolds in a dynamic context under the shadow of a crescent China and a waning, less-than dependable ally in the United States.European Commission action plan states that:The Commission intends to step up border management support at Libya’s Southern border, while in parallel strengthening cross-border cooperation between Libya and its bordering countries in the South, including Niger.Increasingly, voices in the EU call for either a greater level of integration than ever before, or a move in the opposite direction, towards disparate nationalism. Brexit, for its part, has demonstrated that even if presented as greener pastures, the going-it-alone strategy is a risky one at best.The German chancellor, Olaf Scholtz, for his part has indicated an interest in pursuing a German vision of European sovereignty – but it is one that appears to diverge from equivalent notions in France. Though Emanuel Macron may lead the charge on a more militant, assertive vision of Europe, he faces a presidential election in April 2022. While France might hold the 6-month rotating stewardship of the EU, there are no guarantees that French centrist political ambitions will live to see it through.The necessity of a response to the encroachment of Russia on the eastern flank, adds a certain preparatory atmosphere. In this sense, the migrant conundrum offers a formative testing ground for defining and assessing practicalities around sovereignty. But, as with many such crises, the adequacy of the means employed must support the scale of ambitions. And indeed, many believe that it is only the bloc’s united size that will allow it to remain relevant and active on the global stage. “The choice is not between national and European sovereignty,” wrote Jean Pisani-Ferry, a former advisor to Macron, back in December 2019. “It is between European sovereignty and none at all.”For all of these reasons, the Libyan border situation is one that calls for caution. With European sovereignty far from set, any reliance on foreign contractors to bolster security could quickly become problematic. For instance, were the EU to assign projects to companies governed by foreign powers, this could inadvertently, both symbolically and strategically, cede sovereignty to foreign masters. Given the increasing sense of a free-for-all in the realm of private military contractors, confidence is in decline. That is why outsourcing to non-member states could get even more complicated.A European Parliament resolution warned that “no local PSC [private security company] should be employed or subcontracted in conflict regions” and that the EU should favour companies “genuinely based in Europe” and subjected to EU law. However, this resolution has limited scope and is non-binding, therefore its “impact in the theatre remains unclear”.The EU has already had some unfortunate episodes which highlighted the issue of handing out contracts to foreign companies, either local entities or non-European ones working abroad. One noteworthy example was the use of the Canadian firm GardaWorld and British firm G4S in places like Afghanistan. Even though Gardaworld was partnering with the French security company Amarante, Gardaworld always kept leadership in field operations. As a result, the companies’ complete inability to support and evacuate their security personnel during the Kabul Airlift even made headlines last year. The ambiguous role private companies are taking in modern conflicts underlines the need for the EU to work with companies bound by EU law.Following the 2015 migrant crisis, consensus on EU immigration policy took a bruising. And even now, any future definition remains in flux – much like the European project as a whole.Such considerations give an indication of the subtle forces at play in the skirmish for European sovereignty. It remains to be seen what course officials plot on the already incendiary Libyan border. |

| https://www.e-ir.info/2022/01/17/opinion-putins-obsession-with-ukraine-as-a-russian-land/ | Opinion – Putin’s Obsession with Ukraine as a ‘Russian Land’ | Taras Kuzio | 1 | NA |

| https://www.e-ir.info/2022/01/14/opinion-kazakhstans-dark-heritage/ | Opinion – Kazakhstan’s Dark Heritage | Martin Duffy | 1 | NA |

| https://www.e-ir.info/2022/01/13/legitimacy-and-nationalism-chinas-motivations-and-the-dangers-of-assumptions/ | Legitimacy and Nationalism: China’s Motivations and the Dangers of Assumptions | Lewis Eves | 0 | NA |

| https://www.e-ir.info/2022/01/09/business-and-human-rights-overcoming-old-paradigms-pushing-for-new-frontiers/ | Business and Human Rights: Overcoming Old Paradigms, Pushing for New Frontiers | Florian Wettstein | 0 | NA |

| https://www.e-ir.info/2022/01/09/opinion-a-daunting-agenda-for-frances-eu-presidency/ | Opinion – A Daunting Agenda for France’s EU Presidency | Alexander Brotman | 1 | NA |

| https://www.e-ir.info/2022/01/05/rethinking-critical-ir-towards-a-plurilogue-of-cosmologies/ | Rethinking Critical IR: Towards a Plurilogue of Cosmologies | Hartmut Behr and Giorgio Shani | 0 | NA |

| https://www.e-ir.info/2022/01/05/re-thinking-deterrence-in-gray-zone-conflict/ | Rethinking Deterrence in Gray Zone Conflict | Catherine Delafield, Sarah Fishbein, J Andrés Gannon, Erik Gartzke, Jon Lindsay, Peter Schram and Estelle Shaya | 0 | NA |

| https://www.e-ir.info/2022/01/03/chaos-and-corruption-in-west-africa-lessons-from-sierra-leone/ | Chaos and Corruption in West Africa: Lessons from Sierra Leone | Martin Duffy | 0 | NA |

| https://www.e-ir.info/2021/12/31/opinion-looking-behind-the-delimitation-exercise-in-jammu-and-kashmir/ | Opinion – Looking Behind the Delimitation Exercise in Jammu and Kashmir | Maqsood Hussain | 1 | NA |

| https://www.e-ir.info/2021/12/28/debating-the-legacies-of-james-m-buchanan-and-neoliberalism/ | Debating the Legacies of James M. Buchanan and Neoliberalism | Craig Myers | 0 | NA |

| https://www.e-ir.info/2021/12/28/my-order-my-rules-china-and-the-american-rules-based-order-in-historical-perspective/ | ‘My Order, My Rules’: China and the American Rules-Based Order in Historical Perspective | William M. Zolinger Fujii | 0 | NA |

5.3 A for Loop

## [1] "https://www.e-ir.info/2022/01/17/opinion-putins-obsession-with-ukraine-as-a-russian-land/"for(i in 1:5){

text <- read_html(df[i,"url"]) %>%

html_nodes(".-inset article") %>%

html_text() %>%

str_replace_all("[\r\n]" , " ") %>%

str_remove("(.*)(Shutterstock|Loading views)") %>%

str_remove_all("[:graph:]{50,1000}") %>%

str_remove_all("[:space:]{2,}") %>%

str_remove_all("(Further Reading|References)(.*)")

df[i,"text_loop"]<-text

}| url | title | authors | opinion | text | text_loop |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| https://www.e-ir.info/2022/01/19/opinion-the-libyan-border-as-a-testing-ground-for-european-sovereignty/ | Opinion – The Libyan Border as a Testing Ground for European Sovereignty | Robert Palmer | 1 | Migrants and asylum seekers use the Central Mediterranean route to enter the EU out with regulated processes. The journey is dangerous, requiring a departure from North Africa across the Mediterranean Sea to reach Europe’s shores. Since the fall of Gaddafi in 2011, Libya has become one of the main gateways for illegal migration to Europe. The EU aims to lock the North African nation down as a transit point by deploying a border assistance mission. Immediately, this tactic is a means of tackling problematic immigration beyond Europe’s borders. But it is also an opportunity – to be won or lost – that could play a crucial role in defining and asserting the bloc’s as-of-yet-undetermined stance on ‘sovereignty’.With so many migrants travelling through Libya, smuggling and trafficking networks there have erupted. Those on the ground claim the country has become a nexus of coercion, torture, and deprivation. The instability unleashed by the Libyan civil war has dragged roughly 650,000 migrants into dire conditions. Those living in the Libya-based migrant community are reportedly “vulnerable to extortion, violence, and slave-like work conditions,” while migrants held in detention centres there “may experience overcrowding, sexual abuse, forced labour, torture, and deprivation of food, sunlight, and water.”Pressure on the EU is mounting. On the one hand, there are the practical considerations — a collection of nations struggling with the flow of people simply trying to escape horrifying circumstances. On the other hand, there is the challenge of dealing with the problem in a humane and distinctively European way: this last part, in fact, might create the greater trouble for lawmakers.A United Nations report states that, in all likelihood, the lack of human rights protection for migrants at sea,is not a tragic anomaly, but rather a consequence of concrete policy decisions and practices by the Libyan authorities, the European Union Member States and institutions, and other actors.To its credit, the EU has made clear that it plans to improve the situation. While this move is a vital one, it is also a crucial moment for a nascent idea of European sovereignty. The situation unfolds in a dynamic context under the shadow of a crescent China and a waning, less-than dependable ally in the United States.European Commission action plan states that:The Commission intends to step up border management support at Libya’s Southern border, while in parallel strengthening cross-border cooperation between Libya and its bordering countries in the South, including Niger.Increasingly, voices in the EU call for either a greater level of integration than ever before, or a move in the opposite direction, towards disparate nationalism. Brexit, for its part, has demonstrated that even if presented as greener pastures, the going-it-alone strategy is a risky one at best.The German chancellor, Olaf Scholtz, for his part has indicated an interest in pursuing a German vision of European sovereignty – but it is one that appears to diverge from equivalent notions in France. Though Emanuel Macron may lead the charge on a more militant, assertive vision of Europe, he faces a presidential election in April 2022. While France might hold the 6-month rotating stewardship of the EU, there are no guarantees that French centrist political ambitions will live to see it through.The necessity of a response to the encroachment of Russia on the eastern flank, adds a certain preparatory atmosphere. In this sense, the migrant conundrum offers a formative testing ground for defining and assessing practicalities around sovereignty. But, as with many such crises, the adequacy of the means employed must support the scale of ambitions. And indeed, many believe that it is only the bloc’s united size that will allow it to remain relevant and active on the global stage. “The choice is not between national and European sovereignty,” wrote Jean Pisani-Ferry, a former advisor to Macron, back in December 2019. “It is between European sovereignty and none at all.”For all of these reasons, the Libyan border situation is one that calls for caution. With European sovereignty far from set, any reliance on foreign contractors to bolster security could quickly become problematic. For instance, were the EU to assign projects to companies governed by foreign powers, this could inadvertently, both symbolically and strategically, cede sovereignty to foreign masters. Given the increasing sense of a free-for-all in the realm of private military contractors, confidence is in decline. That is why outsourcing to non-member states could get even more complicated.A European Parliament resolution warned that “no local PSC [private security company] should be employed or subcontracted in conflict regions” and that the EU should favour companies “genuinely based in Europe” and subjected to EU law. However, this resolution has limited scope and is non-binding, therefore its “impact in the theatre remains unclear”.The EU has already had some unfortunate episodes which highlighted the issue of handing out contracts to foreign companies, either local entities or non-European ones working abroad. One noteworthy example was the use of the Canadian firm GardaWorld and British firm G4S in places like Afghanistan. Even though Gardaworld was partnering with the French security company Amarante, Gardaworld always kept leadership in field operations. As a result, the companies’ complete inability to support and evacuate their security personnel during the Kabul Airlift even made headlines last year. The ambiguous role private companies are taking in modern conflicts underlines the need for the EU to work with companies bound by EU law.Following the 2015 migrant crisis, consensus on EU immigration policy took a bruising. And even now, any future definition remains in flux – much like the European project as a whole.Such considerations give an indication of the subtle forces at play in the skirmish for European sovereignty. It remains to be seen what course officials plot on the already incendiary Libyan border. | Migrants and asylum seekers use the Central Mediterranean route to enter the EU out with regulated processes. The journey is dangerous, requiring a departure from North Africa across the Mediterranean Sea to reach Europe’s shores. Since the fall of Gaddafi in 2011, Libya has become one of the main gateways for illegal migration to Europe. The EU aims to lock the North African nation down as a transit point by deploying a border assistance mission. Immediately, this tactic is a means of tackling problematic immigration beyond Europe’s borders. But it is also an opportunity – to be won or lost – that could play a crucial role in defining and asserting the bloc’s as-of-yet-undetermined stance on ‘sovereignty’.With so many migrants travelling through Libya, smuggling and trafficking networks there have erupted. Those on the ground claim the country has become a nexus of coercion, torture, and deprivation. The instability unleashed by the Libyan civil war has dragged roughly 650,000 migrants into dire conditions. Those living in the Libya-based migrant community are reportedly “vulnerable to extortion, violence, and slave-like work conditions,” while migrants held in detention centres there “may experience overcrowding, sexual abuse, forced labour, torture, and deprivation of food, sunlight, and water.”Pressure on the EU is mounting. On the one hand, there are the practical considerations — a collection of nations struggling with the flow of people simply trying to escape horrifying circumstances. On the other hand, there is the challenge of dealing with the problem in a humane and distinctively European way: this last part, in fact, might create the greater trouble for lawmakers.A United Nations report states that, in all likelihood, the lack of human rights protection for migrants at sea,is not a tragic anomaly, but rather a consequence of concrete policy decisions and practices by the Libyan authorities, the European Union Member States and institutions, and other actors.To its credit, the EU has made clear that it plans to improve the situation. While this move is a vital one, it is also a crucial moment for a nascent idea of European sovereignty. The situation unfolds in a dynamic context under the shadow of a crescent China and a waning, less-than dependable ally in the United States.European Commission action plan states that:The Commission intends to step up border management support at Libya’s Southern border, while in parallel strengthening cross-border cooperation between Libya and its bordering countries in the South, including Niger.Increasingly, voices in the EU call for either a greater level of integration than ever before, or a move in the opposite direction, towards disparate nationalism. Brexit, for its part, has demonstrated that even if presented as greener pastures, the going-it-alone strategy is a risky one at best.The German chancellor, Olaf Scholtz, for his part has indicated an interest in pursuing a German vision of European sovereignty – but it is one that appears to diverge from equivalent notions in France. Though Emanuel Macron may lead the charge on a more militant, assertive vision of Europe, he faces a presidential election in April 2022. While France might hold the 6-month rotating stewardship of the EU, there are no guarantees that French centrist political ambitions will live to see it through.The necessity of a response to the encroachment of Russia on the eastern flank, adds a certain preparatory atmosphere. In this sense, the migrant conundrum offers a formative testing ground for defining and assessing practicalities around sovereignty. But, as with many such crises, the adequacy of the means employed must support the scale of ambitions. And indeed, many believe that it is only the bloc’s united size that will allow it to remain relevant and active on the global stage. “The choice is not between national and European sovereignty,” wrote Jean Pisani-Ferry, a former advisor to Macron, back in December 2019. “It is between European sovereignty and none at all.”For all of these reasons, the Libyan border situation is one that calls for caution. With European sovereignty far from set, any reliance on foreign contractors to bolster security could quickly become problematic. For instance, were the EU to assign projects to companies governed by foreign powers, this could inadvertently, both symbolically and strategically, cede sovereignty to foreign masters. Given the increasing sense of a free-for-all in the realm of private military contractors, confidence is in decline. That is why outsourcing to non-member states could get even more complicated.A European Parliament resolution warned that “no local PSC [private security company] should be employed or subcontracted in conflict regions” and that the EU should favour companies “genuinely based in Europe” and subjected to EU law. However, this resolution has limited scope and is non-binding, therefore its “impact in the theatre remains unclear”.The EU has already had some unfortunate episodes which highlighted the issue of handing out contracts to foreign companies, either local entities or non-European ones working abroad. One noteworthy example was the use of the Canadian firm GardaWorld and British firm G4S in places like Afghanistan. Even though Gardaworld was partnering with the French security company Amarante, Gardaworld always kept leadership in field operations. As a result, the companies’ complete inability to support and evacuate their security personnel during the Kabul Airlift even made headlines last year. The ambiguous role private companies are taking in modern conflicts underlines the need for the EU to work with companies bound by EU law.Following the 2015 migrant crisis, consensus on EU immigration policy took a bruising. And even now, any future definition remains in flux – much like the European project as a whole.Such considerations give an indication of the subtle forces at play in the skirmish for European sovereignty. It remains to be seen what course officials plot on the already incendiary Libyan border. |

| https://www.e-ir.info/2022/01/17/opinion-putins-obsession-with-ukraine-as-a-russian-land/ | Opinion – Putin’s Obsession with Ukraine as a ‘Russian Land’ | Taras Kuzio | 1 | NA | Everybody is a ‘Ukraine expert’ these days, or are they? Practically none of the multitude of Western commentaries about the Russian threat to invade Ukraine have mentioned Russian President Vladimir Putin’s obsession with Ukraine as a ‘Russian land’ that needs to be re-taken back from Washington’s control as the driving factor of the worst crisis in Europe since the 1960s.As I have explained in my book Crisis in Russian Studies?, Western scholars have either downplayed Russian nationalism in Putin’s Russia or not wanted to deal with the consequences. As I analyse in Russian Nationalism and the Russian-Ukrainian War published on 27 January, the USSR recognised a Ukrainian identity different (but close) to Russian; Soviet Ukraine even had a seat at the UN (the USSR had three seats). Russian nationalism under Putin has stagnated to that of the pre-Soviet era and White Russian emigres which denies the very existence of a Ukrainian state and Ukrainian people. Putin and other Russian officials repeatedly state Russians and Ukrainians are ‘one people.’ Russian information warfare repeats this racism on a daily basis and denigrates Ukraine and Ukrainians in a manner commonly found among pre-1945 Western colonialists.As seen in Putin’s 6,000 word article published in July, at the heart of Putin’s demand is an utter disdain for Ukraine and an unwillingness to accept it is a sovereignand independent country.As the liberal British Observer newspaper wrote: ‘The Russian view that Ukraine is stolen territory to which it has a natural right has roots in tsarist times and before. Ukrainians (and Belarusians) were habitually called ‘little Russians’. Indigenous narratives stress a common history and common faith indissolubly linking two brotherly eastern Slavic races. Putin has repeatedly stated that ‘Russians and Ukrainians are one people’.The Observer continued: ‘Conveniently forgotten is 19th-century imperial oppression that included a ban on Ukraine’s language’ followed by‘a man-made ‘terror famine’ (Holodomor) that killed 4-5 million ‘and is now officially viewed as a Soviet genocide.’ Although this crisis is taking place in the early 21st century, Putin’s views of Ukraine as part of ‘Russia’ ‘recalls that of 1950s France towards Algeria and of 19th-century England towards Ireland.’ Indeed, I have explored the similarities between British and Russian chauvinism towards the Irish and Ukrainians respectively and that of Ulster and Donbas empire loyalists.Putin and the Kremlin believe Ukraine is ruled by a ‘fascist junta’ that came to power in the Euromaidan Revolution and transformed the country into a US puppet state. In their dystopian world, Russian leaders do not feel the need to explain how ‘fascist’ Ukraine can be led by a Jewish-Ukrainian president, Volodymyr Zelenskyy. Or explain how a ‘fascist’ regime is suppressing Russophones when a Russian-speaker (Zelenskyy) won a landslide in the 2019 Ukrainian elections?The Kremlin’s complete control of the media in Russia makes it difficult for most Russians to understand these contradictions in official disinformation. 68% of Russians blame the US and NATO and Ukraine for the escalation of the war this year and only 6% Russia and its two proxy entities in occupied Donbas. While Russian media push ‘civil war’ disinformation about the conflict in eastern Ukraine, approximately three quarters of Ukrainians believe their country is already at war with Russia. When we therefore discuss the question of ‘Will Russian invade?’ we need to remember that this already happened in 2014-2015 in Crimea and theRussian President and Prime Minister Dmitri Medvedev’s, now deputy head of the Russian Security Council, showed complete disdain for Ukraine’s independence in his October 2021 article. Medvedev echoed the Kremlin’s official line that Ukraine is a US puppet state, ruling out talking to Ukraine’s President Volodymyr Zelenskyy as a waste of time and instead calling for talks with its alleged US puppet master. As Medvedev wrote, ‘it makes no sense for us to deal with the vassals. Business must be done with the overlord’.Because Ukraine is a ‘Russian land’ it has no right to decide its own future and should be, forcibly if need be, returned to the Russian World. The Russian World brings together Ukrainians (‘Little Russians’) and Belarusians (‘White Russians’) under Russian (‘Great Russian’) leadership. All three are now viewed by Putin – as in the Tsarist era – as the pan-Russian nation (obshcherusskiy narod).Contemporary pan-Russianism is as much a threat to European security as pan-Germanism was in the 1930s. The two are identical in demanding the unity of ‘Russian’ (or Russian speaking) and German speaking peoples. In the 1930s, the pan-Germanists were obsessed with Poland while today the pan-Russianists are obsessed with Ukraine.In December 2021, Putin presented Europe and the US with a demand for written security guarantees or Russia will resort to ‘military-technical means’. US-Russian, NATO-Russian and OSCE summits in the second week of January produced no positive breakthrough as the West would never have agreed to Putin’s ultimatums Putin has long sought a second agreement modelled on that signed by the great powers in Yalta in 1945 where the US would recognise Eurasia as Russia’s exclusive sphere of influence and Ukraine as part of that sphere.Russia’s penchant for a second Yalta agreement akin to that in 1945 would never have taken place; while Putin has not the world has moved on. Russia’s leaders are nostalgic for the Cold War when the Soviet Union and the US negotiated how to run the world and divide it into spheres of influence. ‘The US has consistently expressed support for the principle that every country has the sovereign right to make its own decisions with respect to its security,’ a US official said. ‘That remains US policy today and will remain US policy in the future.’With the failure of diplomacy to reach a way out of an artificially manufactured crisis, Europe is faced, according to a leaked US intelligence report with the threat of a Russian military invasion of Ukraine in January-February. US intelligence was of good enough quality to have convinced doubters in the EU and NATO of the seriousness of the Russian threat to invade Ukraine when it was circulated to the November 2021 meeting of NATO foreign ministers in Riga. Western diplomats are being warned to be ready to quickly evacuate, presumably if some of Russian military attack takes place.Putin’s brinkmanship creates the biggest threat to European security since the 1961 Cuban missile crisis and should be understood in four ways. The first is the threat to Russia’s own political stability. Putin’s occupation of Crimea has remained popular among Russians over the seven years since the peninsula was invaded. An average of 84-86% of Russians, including some members of the opposition such as imprisoned Alexei Navalny, support Crimea’sis not true of the Donbas region of eastern Ukraine which has no historical symbolismin Russian nationalism. Putin has therefore hidden Russia’s military aggression against Ukraine by describing what is taking place in the Donbas as a ‘civil war’. As the Levada Centre, Russia’s last independent sociological service, recently wrote: ‘To imagine that the Ukrainian army is at war with the Russian one is beyond the imagination of Russians.’ While 37% of Russians believe the conflict could transform into a Russian-Ukrainian war, 55% do not.A full-scale invasion of Ukraine would destroy Putin’s seven-year myth of a ‘civil war’ by showing Russia is at war with its neighbour. This ‘civil war’ myth has been used by Putin to hide the conflict from the Russian population while allowing Russia to have its cake and eat it by sitting at the negotiating table to find a peaceful outcome to a war the Kremlin is itself undertaking against Ukraine.British expert on Russian security Mark Galeotti believes that ‘A vicious war in Ukraine could shatter the unity and legitimation of the Russian regime.’ Russian sociologist Olga Kryshtanovskaya writes that an open Russian-Ukrainian war, ‘would be incredibly unpopular with the Russian people.’ A Russian occupation of Ukraine would be bloody and costly to Russian forces with the large number of body bags returning to Russia adding to the threats to the stability of Putin’ssecond threat is that an invasion would – like in 2014 – again show how Russian stereotypes of Ukraine have nothing in common with reality. Because Russian leaders believe Ukrainians are ‘Little Russians’ under ‘fascist’ and US control, an invading force would be welcomed with bread and salt as liberators. This is not true. About two thirds of Ukrainian troops fighting against Russian proxies in the Donbas are eastern Ukrainians and Russian speakers. The highest casualties of Ukrainian security forces are to be found in Dnipropetrovsk.Thirdly, an invading force needs to have a 3:1 ratio to succeed against well-dug in defending forces. With Ukraine’s 260,000-strong army, the third largest in Europe, would require upwards of two thirds of Russia’s entire army to subdue. Coupled with this number are one million reservists of whom 400,000 are battle hardened veterans of the Donbas war. Each of Ukraine’s 25 regions has a territorial defence force that would become partisans after an invasion. Russia could invade Ukraine and possibly defeat its army, but it would be impossible for Putin to achieve his end goal of transforming Ukraine into a copy of Alexander Lukashenka’s Belarus. A Russian occupation of Ukraine would require levels of pacification of the occupied population that would make repression in Belarus since last year’s elections look like a Sunday picnic.If Ukraine is invaded it would be inevitable that the US and some other NATOmembers would aim to transform it, in the words of US Senator Chris Murphy, into Russia’s ‘next Afghanistan’. The USCongress is sending ‘increased military systems’ and will ‘dramatically increase the amount of lethal aid [to Ukraine]’. NATO special forces have been training and learning from their Ukrainian counterparts since 2014. NATO provides support on countering cyber attacks of the type Ukraine was hit on the 13 January. The US is also to offer Ukraine intelligence on impending Russian military movements and attack plans.The roots of this artificial crisis lie in Putin’s pan-Russianist obsession that Ukraine is a ‘Russian land’ and Ukrainians are a branch of the pan-Russian nation. Everything else flows from that. If Ukraine is ‘Russian’ it has no right to decide a destiny separate to Russia’s. As long as Western scholars continue to dismiss or downplay nationalism in Russia, they will be unable to see the wood for the trees about the worst crisis in Russia’s relations with the West for the last six decades. |

| https://www.e-ir.info/2022/01/14/opinion-kazakhstans-dark-heritage/ | Opinion – Kazakhstan’s Dark Heritage | Martin Duffy | 1 | NA | As Kazakstan’s President Tokayev faces an unprecedented challenge from popular protest or “foreign terrorists” or internal coup (or a combination of all three) it is worth reflecting on the dark heritage of this former Soviet state. That Tokayev’s interior ministry recently confirmed that 9,900 people had been detained in the aftermath of the violence, refreshes the memory of the days when Kazakstan was a key point in the Soviet Gulag Archipelago.Solzhenitsyn used the word archipelago as a metaphor for political camps, which were scattered like hellish islands extending from the “Bering Strait across the Bosporus.” The biggest of these notorious facilities, the Kazak corrective labor camp at Karlag, Karanganda, was the pride of the Kremlin’s Gulag system. Established in 1930 it became the home for thousands of convict laborers and political dissidents and by the time of closure in 1959 had tortured over a million prisoners. Karlag was among the largest Gulag camps. Prisoners were brought to Karlag in shackles by train, packed into boxcars like freight. Most had been charged as “enemies of the workers” under the arbitrary Article 58 of the Soviet Penal Code.Controlled from Moscow by the fearsome NKVD (secret police) prisoners who committed certain crimes were placed in special punishment cells notorious for their use of extreme heat and cold. Particularly intractable prisoners were housed in water tanks, depriving them of sleep. At first religious leaders, writers, and then anyone accused of regime disloyalty was subjected to repression. NKVD also arrested the wives and children of the “enemies of the people.”There was a massive childhood morbidity at these camps between 1930–1940 creating what is now gruesomely called “the Mommy’s cemetry”. Many were locked up for decades only for reading foreign textbooks. The living conditions of women did not differ from men. The women had only one advantage – they were rarely shot, but alas they were frequently subjected to sexual abuse.Known Gulag prisoners included Lev Gumilyov (son of Anna Akhmatova and Nikolai Gumilyov); Rakhil Messerer-Plisetskaya (mother of famous ballerina Maya Plisetskaya); Alexandr Yesenin (son of Russian poet Sergei Yesenin); as well as the leading Kazakh public figures like Ahmet Baitursynov and Gazymbek Birimzhanov,Probably Karlag’s most famous inmate was the German writer Margarete Buber-Neumann. Author of Under Two Dictators (a memoir of Karlag) Margarete went on to survive a Nazi concentration camp. Her husband Heinz had been executed during Stalin’s Great Purge. She survived five years in Nazi Ravensbruck. Living in Sweden and later Germany, and encouraged by her friend Arthur Koestler, she wrote about her years in both Soviet prison and Nazi concentration camps, including her time in Kazakstan. Predictably it aroused the bitter hostility of the Soviet and German communists but ensured that the detail of these torture camps was internationally understood.On 23 February 1949, Buber-Neumann testified in support of Victor Kravchenko, author of the best-selling autobiography, Choose Freedom, following his defection from the Soviet Union. Kravchenko was suing agents of the French Communist Party for libel after it accused him of fabricating his account of Soviet labor camps. Buber-Neumann corroborated Kravchenko’s account, securing his victory.Buber-Neumann continued to write for the next three decades. The same year, she joined the anti-communist Congress for Cultural Freedom with Arthur Koestler and Bertrand Russell. Of Communism and Nazism, Buber-Neumann wrote: “Between the misdeeds of Hitler and those of Stalin there exists only a quantitative difference… I don’t know if the Communist idea, if its theory, already contained a basic fault or if only the Soviet practice under Stalin betrayed the original idea and established in the Soviet Union a kind of Fascism…” She died aged 88 on November 6, 1989, in Germany, just three days before the fall of the Berlin31 is the Day of Remembrance of the Victims of Political Repression in Kazakhstan, but it is a low-key affair. Kazakstan has experienced a careful political memorializing of the Soviet Gulags into national historic sites. Two Gulag museums, Alzhir (the Akmolinsk Camp for Wives of Traitors to the Motherland), and Karlag (the former Karaganda Corrective Labour Camp) opened in 2007 and 2011, respectively. Historical experience of Soviet brutality is watered down to create a more acceptable history. The Gulag tragedies are ‘justified’ by the ideologies of the time, and selective in what they say. This reflects a genuine if partial societal amnesia of the past. Such convenient loss of memory is a response to the collective trauma experienced by the population of Kazakhstan during the Soviet era. It should not be forgotten that during the Kengir uprising in 1954, Karlag’s inmates pushed the Soviets out and held the complex for forty days.Nevertheless, in Kazakhstan today, a significant percentage of people have living family whose life trajectories included deportation and imprisonment in the camps. A monument in Almaty, Kazakhstan commemorates an anti-Soviet protest in 1986, but the government, partly because of its pro-Russian foreign policy, discourages remembrances of selected historical events. There are political aspects to a sidestepping of Kazakhstan’s recent history, too, often born out of the government’s determination to stay friendly with Russia. To sustain support for a pro-Russia foreign policy, Kazakhstan seemingly ignores its colonial and neo-colonial history with Russia. Although those efforts have not added up to a ban on public remembrance, the government is wary- censoring via the education system and state media such as KazakhFilm.Visitors to today’s Karlag Gulag Museum Complex will find an impressive modern building which does not immediately embody dark heritage. Inside there are 3 floors of exhibits, convict art, propaganda posters and dioramas showing what life was like within the gulag system. A basement houses a gruesome series of prison cells, torture rooms and execution equipment, overlooked by approving busts of Lenin. The museum was able to find prison records for January 1959, the year it closed, that show 16,957 prisoners incarcerated across Karlag, a noticeable drop from the high of 65,673 recorded in January 1949.The Karlag museum receives a score of 7 out of 10 on dark-tourism.com’s “darkometer” scale. By comparison, Auschwitz, and Hiroshima both score 10. Exhibits include the horrors of the famine that ravaged Kazakhstan between 1919 and 1922 killing 500,000 people. The famine, along with the violent crushing of anti-Soviet rebellions, are described as “the most terrible offenses against mankind” but no explanations are offered.The complex comprises a small but elegant museum, a memorial and a well-preserved Stolypin car, a basic railway carriage used for transporting prisoners. One of the first things the visitor sees upon entering is a quote by the former President of Kazakhstan, Nursultan Nazarbayev: “the Gulag camp system was a crime against humanity!” However, this is not shouted too loudly, especially at times when the President might require Moscow’s help.The museum suggests Karlag’s purpose was to feed the prison system in Kazakhstan; in other words, it dealt in agriculture. Karlag was reorganized into the state farm Gigant and the camp, which held about 65,000 inmates at its peak, became the largest sovkhoz in the Soviet Union. Kazakhstan has done something that would be unthinkable in Russia. The past has been declared a national tragedy and the whole country has been turned into a huge memorial, but Russia manages to escape blame, as if decades of persecution had been committed by alien invaders.Former President Nazarbayev, now 81, shrewdly embellished commemoration of the Gulag with a strange system of ritualized interpretations, which unified each ethnic group in memory of the Gulag on the side of the victims, while the blame is placed on the faceless NKVD or “Stalinist system”.Modern Kazakhstan has a penchant for re-writing history, which means the events of recent weeks, alarm its leaders.Kazakhstan’s current president has said troops from a Russian-led military bloc will soon withdraw. Tokayev had asked for assistance from the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO) to regain control, after unrest that left at least 164 people dead. Amidst fears of a permanent Russian foothold in Kazakhstan, Tokayev insists the withdrawal would beginexecuted a ruthless crackdown after protests over rising fuel prices were allegedly exploited by violent groups, who attacked government buildings and briefly seized the airport in Almaty. He has described those involved as “terrorists” with shadowy foreign backers. Former President Nazarbayev has remained absent from public view since the protests began, and Tokayev removed him from his position as head of the national security council, as well as sacking his security boss. The extreme wealth accumulated by the Nazarbayev dynasty has contributed to the mood of protest, and fueled fears of regime infighting. Russian troops on Kazak soil are unpleasant reminders of Kazakhstan’s dark heritage and bring unwelcome memories of Solzhenitsyn’s “Gulag Archipelago” in this politically unstable part of Central Asia. |

| https://www.e-ir.info/2022/01/13/legitimacy-and-nationalism-chinas-motivations-and-the-dangers-of-assumptions/ | Legitimacy and Nationalism: China’s Motivations and the Dangers of Assumptions | Lewis Eves | 0 | NA | There is increasing anxiety in the West about China’s growing assertiveness on the international stage. This anxiety is evident in the policies of western states. The USA has described China as ‘a sustained challenge’ to the international system (The White House, 2021 p.8). Meanwhile, the UK is investing in its ‘China-facing capabilities’ and Australia is purchasing nuclear submarines to hedge against China’s presence in the South China Sea (HM Government, 2021 p.22; Masterson, 2021). Undoubtedly, China’s rise poses a challenge to the status quo. If for no other reason than that it represents an alternative to the western-centric international system (Turin, 2010). Nevertheless, representing an alternative to the status quo does not mean that Chinese foreign policy is inherently motivated by challenging the West.Such anxious perspectives of Chinese foreign policy are rooted in realism, a theory of international relations which assumes actors to be inherently self-interested and motivated by the egoistic pursuit of power (Waltz 2001; Mearshimer 2003). According to this ontology, the potential power to be gained by acting assertively is enough to account for China’s foreign policy motivations. Social constructivism, on the other hand, posits that an actor’s motivations are rooted in the social interactions between groups within the state (Leira, 2019). Using this lens, China’s foreign policy motivations must be understood in relation to its domestic politics. Adopting a socially constructivist ontology, this article argues that Chinese foreign policy is motivated, at least in part, by domestic nationalist pressures and that, by way of the security paradox, western policies are fuelling Chinese assertiveness.This article proceeds as follows. Firstly, by presenting the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP’s) twin-pillar model of legitimacy and its increased reliance on nationalism to maintain its regime’s legitimacy. It then outlines China’s nationalist movement and its foreign policy agenda, using the 2010 Senkaku/Diaoyu dispute to show how nationalist pressure affects the CCP’s foreign policy decision-making. Consideration is then given to the CCP’s social controls, showing that the CCP is unable to mitigate nationalist pressure via its propaganda infrastructure. The final section then presents the security paradox concept and how the West’s realist assumptions and anxious policies are fuelling Chinese assertiveness.Pillars of LegitimacyAfter Mao’s death, the CCP could no longer rely upon a cult of personality to provide popular support for its regime (Coble, 2007). Rather, the CCP has since premised its regime legitimacy ‘upon the twin pillars of nationalism and economic prosperity (Reilly, 2004 p.283). This model of legitimacy predicates the CCP’s regime security upon its ability to improve the economic conditions of the Chinese people and its ability to protect and pursue China’s nationalthe CCP has closely associated itself with China’s economic success and national interests. The CCP-owned People’s Daily, for example, regularly praises the CCP for fostering China’s ‘thriving and diverse economy’ (Cai, 2021). It goes as far as to praise specific CCP economic policies such as the 13th Five Year Plan, which is credited with growing China’s digital economy by 16.6% from 2016-20 (People’s Daily Online, 2021a). Also published were calls to support the CCP in protecting national interests from foreign intervention. For example, by purchasing Xinjiang Cotton against the backdrop of international condemnation of China’s treatment of Xinjiang’s Uighur population (People’s Daily Online, 2021b).Notably, Chinese president Xi Jinping invoked both pillars when speaking at the CCP’s 100th-anniversary celebrations. Stating that ‘only socialism with Chinese characteristics can develop China’ (BBC News, 2021) In this statement, the CCP and its specific brand of socialist ideology are presented as essential to China’s economic development. Meanwhile, Xi also made an overtly nationalistic pledge that the CCP will:never allow anyone to bully, oppress or subjugate China. Anyone who tries to do that will have their heads bashed bloody against the Great Wall of Steel forged by over 1.4 billion Chinese people (Xi via BBC News, 2021).Evidently, the CCP is eager to associate itself with economic development and protecting the Chinese nation. Doing so in accordance with the twin pillar model to maintain its regime legitimacy.However, an emerging issue with the twin pillar model is that the CCP increasingly struggles to ensure economic prosperity. Central to the economic pillar are Deng Xiaoping’s liberal economic reforms. Since their introduction in the early 1980s, per capita income has increased by 2500% and over 800 million Chinese have been saved from poverty, conferring popular support for the CCP’s economic stewardship (Denmark, 2018). Yet, structural economic challenges including a declining labour force, low per-capita productivity, and an over-reliance on manufacturing result in barriers to sustained growth (World Bank, n.d.). Consequentially, 373 million Chinese continue living in some degree of relative poverty (Ibid.).As economic prosperity becomes harder to guarantee, the integrity of the economic pillar is weakened. This is an issue of which the CCP is aware. China’s growth rate in 2018 was 6.6% (Kuo, 2019), significantly below both China’s highs of over 10% growth in the 2000s, and the necessary rate needed to maintain high levels of employment (World Bank, n.d.). This led to concerns among CCP officials that rising unemployment might lead to social unrest (Kuo, 2019). This included Premier Li Keqiang, who publicly acknowledged ‘public dissatisfaction’ over China’s stagnating economic performance (Bradsher and Buckley, 2019).Given the economic pillar’s weakness, the CCP must rely more upon the nationalist pillar to carry the burden of its regime legitimacy. Hence, the CCP has been less likely to constrain popular expressions of nationalist in recent years (Abbott, 2016). In 2005, tens-of-thousands of Chinese nationalists protested Japanese textbooks for their omission of atrocities committed against China during the Second Sino-Japanese War (Watts, 2005). Protesters attacked Japanese businesses and property, including Japan’s embassies and consulates (Yardley, 2005). Some local CCP branches and low-level officials encouraged the demonstrations, but the central CCP discouraged the nationalist demonstrations (Watts, 2005). These efforts included deploying riot police, shutting down public transport and the Minister of Public Security declaring the protests illegal and citing concern for Sino-Japanese relations as the reason for this crackdown (Yardley, 2005).In stark contrast, the CCP did relatively little to stop anti-Japanese protests in 2012. This time, nationalists in over 180 Chinese cities gathered in the tens-of-thousands to protest Japan’s nationalisation of the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands (Gries et al., 2016), an island chain in the East China Sea claimed by China but administered by Japan. Notably, senior CCP officials failed to comment on the protests while the dispute was ongoing (Buckley, 2012). Tensions in Sino-Japanese relations were higher in 2012 compared to 2005 (Gries et al., 2016), meaning it is challenging to isolate China’s economic performance as a variable accounting for the difference in the CCP’s response. However, it is notable that China’s economic growth rate slowed by roughly one-third from 11.39% in 2005 to 7.86% in 2012 (World Bank, n.d.). Accordingly, as per the twin-pillar model, the CCP’s reluctance to constrain the nationalistic anti-Japanese protests was to be expected, any anti-protest measures risking the nationalist credentials upon which the CCP increasingly relied as the economic pillarNationalism and the CCP’s Foreign PolicyThe CCP’s reliance on the nationalist pillar confers considerable influence upon China’s nationalist movement. This in turn requires the CCP to acquiesce to the nationalist agenda in its foreign policy to maintain its legitimating nationalist credentials. Chinese nationalism is not a unified movement but consists of groups and organisations sharing a common Chinese nationalism sensitive to what it considers affronts to the Chinese nation and vocal in its activism against said affronts (Reilly, 2004; Coble, 2007; Johnston, 2017). Some of these groups and organisations have formal links with the CCP, for example, the Communist Youth League and nationalists working in local CCP branches (Watts, 2005; Kecheng, 2020). Others operate more independently of the CCP, such as nationalists among the Chinese diaspora and most of China’s online activist groups (Modongal, 2016; Fang and Repnikova, 2018).These groups subscribe to a broad nationalist agenda and expect the CCP to use China’s growing economic and military strength to pursue China’s interests (Abbott, 2016). Specifically, they demand justice for historical repression, recognition of China commensurate with its newfound strength, that the CCP mobilise against threats to Chinese sovereignty, and that China’s sphere of influence be respected (Boylan et al., 2020). This agenda was evident in the recent US-China trade war. Nationalists called for sanctions in response to what they perceived as a US attempt to reject China’s status as a leading global economy, comparing US tariffs to the repressive economic restrictions imposed upon China by western imperialists in the 1800sthe nationalist agenda and the CCP’s reliance on the nationalist pillar for regime legitimacy is significant. This is because the CCP must adhere to the nationalist agenda in its foreign policy to live up to its nationalist credentials (Coble, 2007). This is apparent in how, against the backdrop of China’s slowing economy, nationalist pressure has coincided with a hard-line stance from the CCP in China’s foreign relations. An example of this can be found as early as the 2010 Senkaku/Diaoyu dispute (also known as the Trawler Incident). This dispute began after a Chinese fishing trawler collided with two Japanese coastguard vessels in the territorial waters of the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands, after which Japan arrested the trawler’s crew. Initially the CCP responded relatively benignly, limited to Foreign Ministry Spokeswoman Jiang Yu issuing a statement requesting that Japan ‘refrain from so-called law-enforcement activities in the East China Sea’ (Johnson 2010).However, nationalistic anti-Japanese protests began in the days following the incident. The protesters called upon the CCP to take further action against Japan. One protester outside the Japanese embassy explained: ‘I want our government to be stronger. They shouldn’t let the Japanese bully us on our own soil!’ (Lim, 2010). Meanwhile, a protester in Shanghai summarised the protests as follows: ‘We came here to appeal for fairness and for the right to ask for our captain back. We regret the government’s weakness in diplomacy’ (Al Jazeera, 2010a).Evidently, the China nationalist movement, in response to a perceived affront in the form of the trawler incident, sought to pressure the CCP into resolving the dispute in accordance with the nationalist agenda. The day after the protests started, and also only a day after their initial statement, Spokeswoman Jiang announced naval deployments to the East China Sea. This demarcated the first instance of regular Chinese patrols in the region since the normalisation of Sino-Japanese relations in the 1970s (Green et al., 2017). In the following weeks, as the nationalistic anti-Japanese protests continued, China also suspended diplomatic contacts with Japan and ceased rare earth exports essential to Japanese manufacturing (Hafeez, 2015). Chinese Premier Wen Jiabao also threatened Japan with retaliation while in New York for a UN conference (Al Jazeera, 2010b).The fact that the CCP pivoted from a diplomatic response to naval deployments within one day, and that this pivot coincided with nationalist pressure upon the CCP, shows nationalism’s affect upon Chinese foreign policy in action. The rapid change in response to Japan resulting from the CCP wanting to uphold its nationalist credentials regardless of the implications for Sino-Japanese relations.Of course, it is plausible that the CCP simply desired to take a strong stance against Japan and that anti-Japanese sentiment merely offered the pretext for the CCP to flex its newfound military strength. Taffer (2020), for example, presents the trawler incident as an attempt by the CCP to test the USA’s commitment to its Japanese ally. However, the CCP made efforts to repair Sino-Japanese relations after the flashpoint of the dispute passed. These included the resumption of rare earth exports and mild discouragement of anti-Japanese protests once nationalist pressure subsided in the following months (Green et al., 2017). This indicates that the CCP did not want to damage Sino-Japanese relations, but rather that nationalist pressure forced the CCP to act in accordance with the nationalist agenda. Thereby safeguarding its nationalist credentials as per its increasing reliance upon the nationalist pillar to secure its regimeLimits of the CCP’s ControlReilly (2011) argues that the CCP practices effective social control over its nationalist movement by leveraging China’s propaganda infrastructure to direct and disperse nationalist sentiment as needed. If true, this would mean that the CCP faces no pressure to adhere to the nationalist agenda. It could merely adapt its propaganda messaging to counter nationalist pressure without appeasing the nationalist agenda in its foreign policy decision-making.Yet, the CCP has failed to restrict nationalist activism against foreign actors, illustrating the limits of the CCP’s control over China’s nationalist movement. For example, in 2020, against the backdrop of international condemnation of events in Hong Kong, the CCP struggled to crackdown on a nationalist anti-foreign smear campaign on social media (Lo, 2020). Notably, the Communist Youth League, a nationalistic youth movement affiliated with the CCP, provocatively endorsed a ‘social media crusade’ against foreign governments sympathetic towards Hong Kong (Kecheng, 2020). This shows that the CCP struggles to exert social control over nationalist organisations it has formal links with, let alone the broader Chinese nationalist movement.The limitations of the CCP’s crackdown on the nationalist social media campaign, and thus limitations of the CCP’s social controls over China’s nationalist movement, were most prominent in May 2020. Chinese nationalist hacktivists hijacked the Twitter account of the Chinese embassy in Paris, posting a picture depicting the USA as the personification of death, trailing blood along a corridor and knocking at Hong Kong’s door with the caption ‘who’s next?’ (Lo, 2020). This is significant for two reasons. Firstly, the response from the Chinese embassy was to rapidly delete the post and issued formal apologies to France and the USA (Keyser, 2020). These actions are inconsistent with a CCP truly motivated to assert China’s national interests to the detriment of its foreign relations, but consistent with a CCP struggling to control China’s nationalist movement.Secondly, and most importantly, this example shows Chinese nationalists to be hijacking the CCP’s propaganda infrastructure to pursue their foreign policy agenda. This points to a reality in which, rather than the CCP having social control of China’s nationalist movement through its propaganda infrastructure, Chinese nationalists find ways to escape the CCP’s social controls. It also shows that they are willing to respond independently of the CCP to perceived affronts to the Chinese nation if they feel the CCP fails to do so adequately.Given the limitations of the CCP’s social controls, the CCP cannot merely adapt its propaganda messaging to offset nationalist pressure. Rather, it must contend with the dilemma of either acquiescing to the nationalist agenda, even to the detriment of China’s foreign relations, or risking its nationalist credentials and thus regime legitimacy. This demonstrates that domestic nationalist pressures are a significant factor in China’s foreign policy decision-making despite the CCP’s propaganda infrastructure.Why Does it Matter?Understanding the nationalist pressures on the CCP’s foreign policy decision-making is important for two reasons. Firstly, from an academic standpoint, it serves as a case study in working past initial assumptions about an actor’s motivations. Whereas western policymakers anxiously assume China’s motivations in accordance with realism, this article has presented an alternative explanation. By looking at an actor’s foreign policy as a product of its domestic politics, it is possible to provide a more meaningful explanation of their foreign policy motivations. In this case, that China is motivated, at least in part, by the CCP’s desire to uphold its legitimating nationalist credentials in the face of pressure to adhere to the foreign policy agenda of its nationalistin terms of the practise of international relations, it shows how the realist assumptions of western policymakers and their respective China policies risk becoming self-fulfilling prophecies. This is in accordance with the security paradox concept. Also known as the security dilemma, the security paradox refers to a cycle in which two sides, through their efforts to mitigate their own uncertainty and insecurity, trigger uncertainty and insecurity in the other (Booth and Wheeler, 2007). As this cycle progresses tensions may escalate to the point that conflict emerges despite, paradoxically, neither side necessarily holding any ill-will towards the other at the start of the paradox (Ibid.). An example of a security paradox is the Anglo-German naval arms race during the prelude to World War I. In this, Germany’s maritime ambitions caused Britain to expand its navy, in turn lea ding Germany to accelerate its naval programme and thus Britain to develop larger battleships, and so on (Maurer, 1997).A similar mechanic can be observed today regarding the West and its policies towards China. Western states, anxious about China’s rise and growing assertiveness, are enacting policies in preparation of a Chinese challenge to the status quo. Purchasing nuclear submarines and investing in ‘China-facing capabilities’. While understandable given their anxiety and realist assumptions, these policies risk provoking Chinese nationalists. Thereby generating pressure on the CCP to enact the assertive foreign policy the West wants to avoid. Likely leading to further western policies that risk being interpreted as an affront by Chinese nationalists. If unchecked, this could lead to hostility despite both the West and the CCP merely attempting to mitigate their own insecurities.That western policies are provoking Chinese nationalists is clear to see. Minister Yang Xiaoguang of the Chinese embassy in London has explained that the Chinese people have expressed ‘antipathy and opposition’ to the UK’s plans to China policy (Embassy of the People’s Republic of China in the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, 2021). This indicates domestic nationalist pressure on the CCP to respond to the UK’s policy. Similarly, in response to American posturing and Australia’s acquisition of nuclear submarines, Chinese nationalists briefly began calls for the CCP to declare war on AUKUS (Davidson and Blair, 2021). These examples both highlight how, in response to western policy, China’s nationalist movement is pressuring the CCP to adhere to its foreign policy agenda. In doing so, making the case that the West is, by way of its China policies, creating the assertive China that fuels their own anxieties.ConclusionEvidently, China’s foreign policy motivations are influenced by domestic nationalist pressures and western policy. This is apparent considering the twin-pillar model. As economic prosperity has become harder for the CCP to guarantee, it has had to increasingly rely upon nationalism for legitimacy. This confers considerable influence upon China’s nationalist movement. China’s nationalist movement subscribes to a broad nationalist agenda, which it wants the CCP to adhere to in its foreign policy decision-making. This has affected China’s foreign policy in practise, apparent as early as 2010 when the CCP quickly pivoted to align more closely to the nationalist agenda during the 2010 Senkaku/Diaoyu dispute. Some have argued that the CCP’s control over China propaganda infrastructure confers effective control over China’s nationalist movement. However, as discussed, the CCP’s social controls over Chinese nationalists are in fact limited. With nationalists even bypassing said propaganda infrastructure and directly pursuing their foreign policy agenda when they consider the CCP to failed to rectify affronts to the Chinesethe domestic pressures motivating Chinese foreign policy showcases the importance of moving beyond realist assumptions and highlights how we can achieve a fuller understanding by considering the domestic when we study the international. It also shows that western foreign policies are, by way of the security paradox, generating the assertive China that western policy was intended to mitigate. As the West provokes Chinese nationalists, they are pressuring the CCP to enact more assertive foreign policies, in turn causing further anxiety in the West. Further study into how China’s domestic politics informs its foreign policy could offer additional insights motivations. It could also inform western policies towards China. Lessening the risk of provoking Chinese nationalists and thus better mitigating western anxieties. |