Chapter 6 Joint Distribution Functions

6.1 Overview

In Section 5 we have introduced the concept of a random variable and a variety of discrete and continuous random variables. However, often in statistics it is important to consider the joint behaviour of two (or more) random variables. For example:

- Height, Weight.

- Degree class, graduate salary.

In this Section we explore the joint distribution between two random variables \(X\) and \(Y\).

6.2 Joint c.d.f. and p.d.f.

where \(x,y \in \mathbb R\).

The function \(f_{X,Y}\) is called the joint probability density function (joint p.d.f.) of \(X\) and \(Y\).

Hence we differentiate the c.d.f. \(F_{X,Y}(x,y)\) with respect to both \(x\) and \(y\) to obtain the p.d.f. \[f_{X,Y}(x,y) = \frac{ \partial^2 \; \; \;\;} {\partial x \partial y} F_{X,Y}(x,y).\]

- Find \(P(X>Y)\),

- Find \(P(X>\frac{1}{2})\).

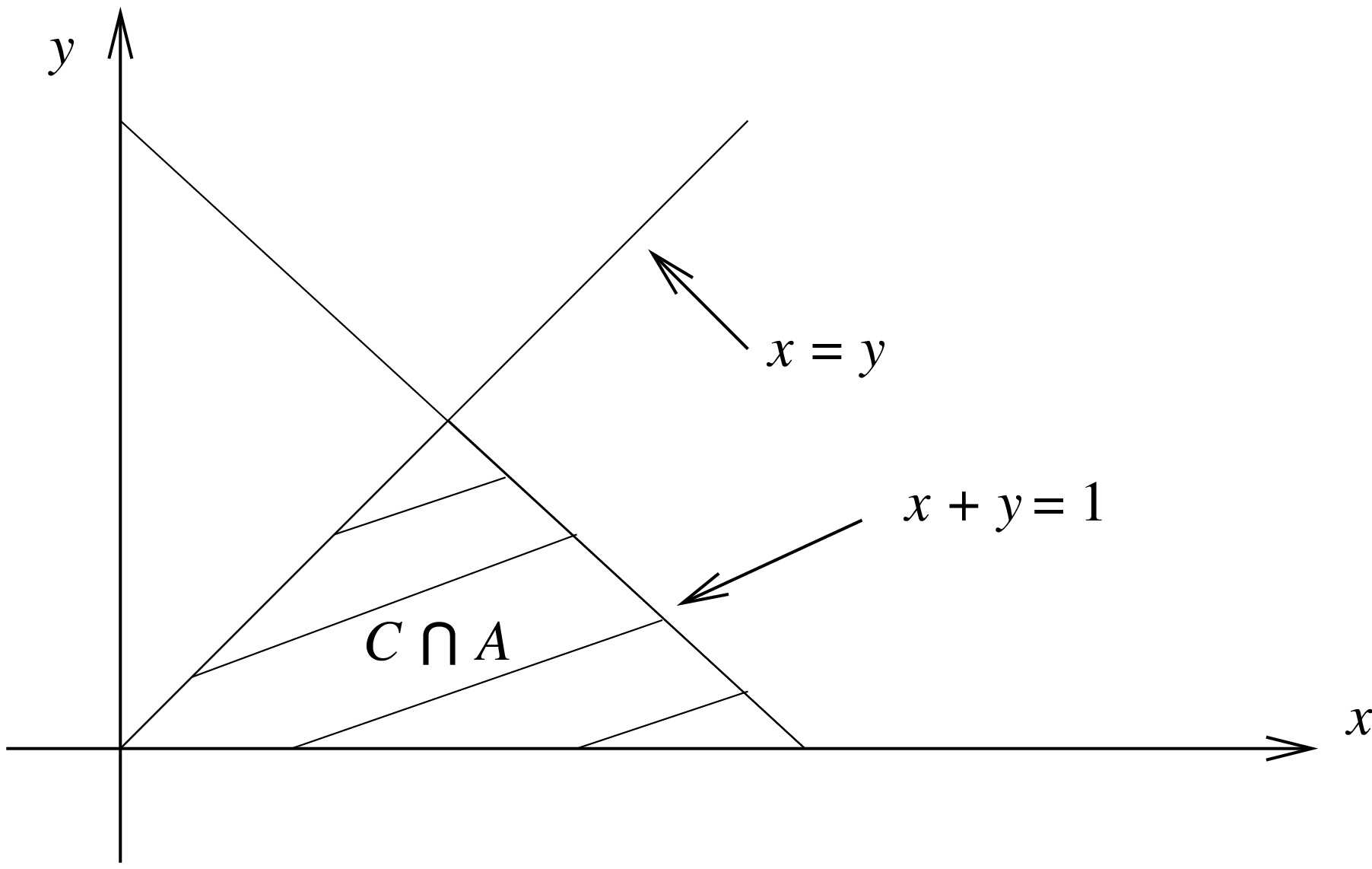

- Let \(C = \{ (x,y): x>y \}\) and write \(A=\{ (x,y):f_{X,Y}(x,y)>0\}\). Then,

- Let \(D = \{ (x,y): x>1/2 \}\), then

6.3 Marginal c.d.f. and p.d.f.

There are many situations with bivariate distributions where we are interested in one of the random variables. For example, we might have the joint distribution of height and weight of individuals but only be interested in the weight of individuals. This is known as the marginal distribution.

Suppose that the c.d.f. of \(X\) and \(Y\) is given by \(F_{X,Y}\), then the c.d.f. of \(X\) can be obtained from \(F_{X,Y}\) since \[\begin{align*} F_X(x) &= P(X \leq x) \\ &=P( X \leq x, Y<\infty ) \\ &= \lim_{y\rightarrow\infty} F_{X,Y}(x,y). \end{align*}\] \(F_X\) is called the marginal distribution (marginal c.d.f.) of \(X\).

If \(f_{X,Y}\) is the joint p.d.f. of \(X\) and \(Y\), then the marginal probability density function (marginal p.d.f.) of \(X\) is given by \[f_X(x) = \int_{-\infty}^\infty f_{X,Y}(x,y) \,dy.\]

Consider Example 1.

Find the marginal p.d.f. and c.d.f of Y.

Attempt Exercise 1 and then watch Video 14 for the solutions.

Video 14: Ratio of Exponentials

Alternatively the solutions are available:

Solution to Exercise 1

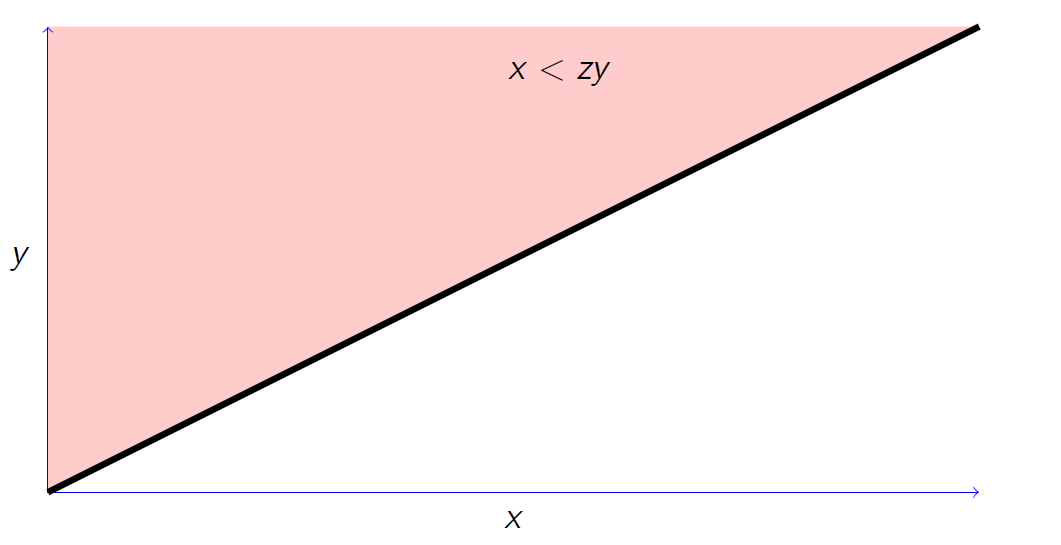

Clearly, \(Z>0\). For \(z>0\),

Note that we can extend the notion of joint and marginal distributions to random variables \(X_1,X_2,\dots,X_n\) in a similar fashion.

6.4 Independent random variables

Random variables \(X\) and \(Y\) are said to be independent if, for all \(x,y \in \mathbb{R}\),

that is, for all \(x,y\in\mathbb R\), \(F_{X,Y}(x,y) = F_X(x) F_Y(y)\).

where both \(X\) and \(Y\) are distributed according to \({\rm Exp} (1)\). Thus the distribution \(Z\) given in Exercise 1 is the ratio of two independent exponential random variables with mean 1.

Note that we can easily extend the notion of independent random variables to random variables \(X_1,X_2,\dots,X_n\).

The random variables \(X_1,X_2,\dots,X_n\) are said to independent and identically distributed (i.i.d.) if,

\(X_1,X_2,\dots,X_n\) are independent.

\(X_1,X_2,\dots,X_n\) all have the same distribution, that is, \(X_i \sim F\) for all \(i=1,\dots,n\).

Definition 6 extends the notion of i.i.d. given at the start of Section 5.4.2 for discrete random variables.

The random variables \(X_1,X_2,\dots,X_n\) are said to be a random sample if they are i.i.d.

Suppose \(X_1,X_2,\dots,X_n\) are a random sample from the Poisson distribution with mean \(\lambda\). Find the joint p.m.f. of \(X_1,X_2,\dots,X_n\).

If \(X_i \sim {\rm Po} (\lambda)\), then its p.m.f. is given by

Since \(X_1,X_2,\dots,X_n\) are independent, their joint p.m.f. is given by,

The joint p.m.f. of \(\mathbf{X} = (X_1,X_2, \ldots, X_n)\) tells us how likely we are to observe \(\mathbf{x}= (x_1,x_2,\ldots, x_n)\) given \(\lambda\). This can be used either:

- To compute \(P (\mathbf{X} = \mathbf{x})\) when \(\lambda\) is known;

- Or, more commonly in statistics, to assess what is a good estimate of \(\lambda\) given \(\mathbf{x}\) in situations where \(\lambda\) is unknown.

Student Exercise

Attempt the exercise below.

Question.

A theory of chemical reactions suggests that the variation in the quantities \(X\) and \(Y\) of two products \(C_1\) and \(C_2\) of a certain reaction is described by the joint probability density functionOn the basis of this theory, answer the following questions.

- What is the probability that at least one unit of each product is produced?

- Determine the probability that quantity of \(C_1\) produced is less than half that of \(C_2\).

- Find the c.d.f. for the total quantity of \(C_1\) and \(C_2\).

Solution to Question.

- The required probability is

\[\begin{eqnarray*} P(X \geq 1, Y \geq 1) & = & \int_1^\infty \int_1^\infty \frac{2}{(1+x+y)^3} \; dy \; dx \\ & = & \int_1^\infty \left[ \frac{-1}{(1+x+y)^3} \right]_{y=1}^\infty \; dx \\ & = & \int_1^\infty \frac{1}{(2+x)^2} \; dx \\ &=& \left[ \frac{-1}{2+x} \right]_{x=1}^\infty = \frac{1}{3}. \end{eqnarray*}\] - The required probability is

\[\begin{eqnarray*} P\left(X \leq \frac{1}{2} Y \right) & = & \int_0^\infty \int_0^{y/2} \frac{2}{(1+x+y)^3} \; dx \; dy \\ & = & \int_0^\infty \left[ \frac{-1}{(1+x+y)^3} \right]_{x=0}^{y/2} \; dy \\ & = & \int_0^\infty \left( \frac{1}{(1+y)^2} - \frac{1}{(1+3y/2)^2} \right) \; du \\ &=& \left[ \frac{-1}{1+y} - \frac{-2/3}{(1+3y/2)} \right]_{y=0}^\infty = \frac{1}{3}. \end{eqnarray*}\] - Since both \(X\) and \(Y\) are non-negative random variables, \(X + Y\) is non-negative. Thus \(P(X + Y \leq z) =0\) for \(z<0\). For \(z \geq 0\),

\[\begin{eqnarray*} P(X + Y \leq z) & = & \int_0^z \int_0^{z-y} \frac{2}{(1+x+y)^3} \; dx \; dy \\ & = & \int_0^z \left[ \frac{-1}{(1+x+y)^3} \right]_{x=0}^{z-y} \; dy \\ & = & \int_0^z \left( \frac{1}{(1+y)^2} - \frac{1}{(1+z)^2} \right) \; du \\ &=& \left[ \frac{-1}{1+y} - \frac{y}{(1+z)^2} \right]_{y=0}^{z} \\ &=& - \frac{1}{1+z} - \frac{z}{(1+z)^2} + 1 + 0 = \left(\frac{z}{1+z} \right)^2. \end{eqnarray*}\]