Chapter 5 Limitations of the pre-post design: biases related to systematic change

5.1 Learning objectives

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to:

- Describe three limitations of common pre-post intervention designs and how these can be addressed

At first glance, assessing an intervention seems easy. Having used the information in Chapter 3 to select appropriate measures, you administer these to a group of people before starting the intervention, and again after it is completed, and then look to see if there has been meaningful change. This is what we call a pre-post design, and it almost always gives a misleadingly rosy impression of how effective the intervention is. The limitations of such studies have been well-understood in medicine for decades, yet in other fields they persist, perhaps because the problems are not immediately obvious.

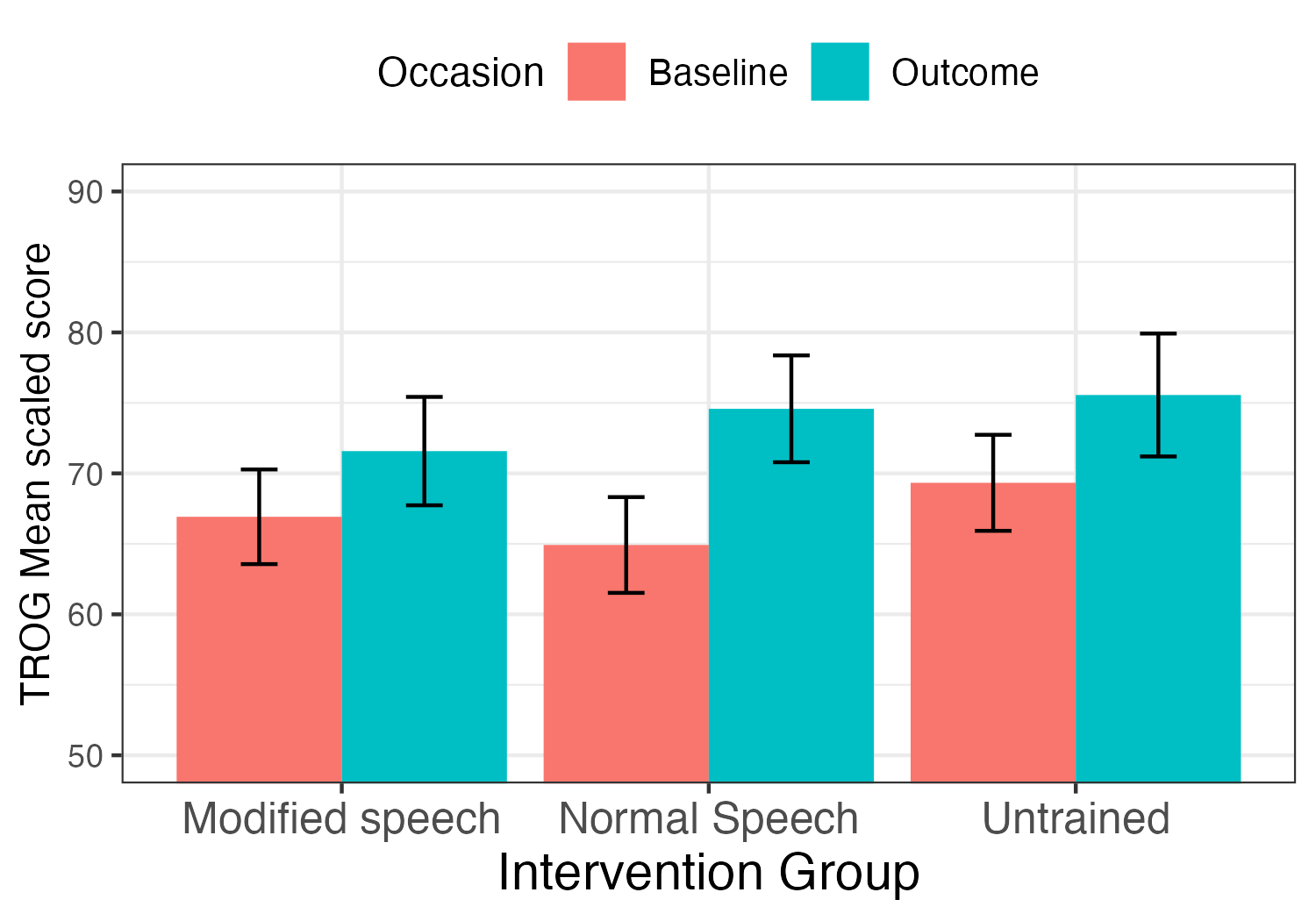

Figure 5.1: Mean comprehension test scores for three groups at baseline and outcome from a study by Bishop et al 2006. Error bars shown standard errors.

Figure 5.1 shows some real data from a study conducted by Bishop et al. (2006), in which children were trained in a computerized game that involved listening to sentences and moving objects on a computer screen to match what they heard. The training items assessed understanding of word order, in sentences such as “the book is above the cup”, or “the girl is being kicked by the boy”. There were two treatment conditions, but the difference between them is not important for the point we want to make, which is that there was substantial improvement on a language comprehension test (Test for Reception of Grammar, TROG-2) administered at baseline and again after the intervention in both groups. If we only had data from these two groups, then we might have been tempted to conclude that the intervention was effective. However, we also had data from a third, untrained group who just had “teaching as usual” in their classroom. They showed just as much improvement as the groups doing the intervention, indicating that whatever was causing the improvement, it wasn’t the intervention.

To understand what was going on in this study, we need to recognize that there are several reasons why scores may improve after an intervention that are nothing to do with the intervention. These form the systematic biases that we mentioned in Chapter 1, and they can be divided into three kinds:

- Spontaneous improvement

- Practice effects

- Regression to the mean

5.2 Spontaneous improvement

We encountered spontaneous improvement in Chapter 1 where it provided a plausible reason for improved test scores in all three vignettes. People with acquired aphasia may continue to show recovery for months or years after the brain injury, regardless of any intervention. Some toddlers who are “late talkers” take off after a late start and catch up with their peers. And children in general get better at doing things as they get older. This is true not just for the more striking cases of late bloomers, but also for more serious and persistent problems. Even children with severe comprehension problems usually do develop more language as they grow older – it’s just that the improvement may start from a very low baseline, so they fail to “catch up” with their peer group.

Most of the populations that speech and language therapists work with will show some spontaneous improvement that must be taken into account when evaluating intervention. Failure to recognize this is one of the factors that keeps snake-oil merchants in business: there are numerous unevidenced treatments on offer for conditions like autism and dyslexia. Desperate parents, upset to see their children struggling, subscribe to these. Over time, the child’s difficulties start to lessen, and this is attributed to the intervention, creating more “satisfied customers” who can then be used to advertise the intervention to others.

As shown in Figure 5.1, one corrective to this way of thinking is to include a control group who either get no intervention or “treatment as usual”. If these cases do as well as the intervention group, we start to see that the intervention effect is not as it seems.

5.3 Practice effects

The results that featured in Figure 5.1 are hard to explain just in terms of spontaneous change. The children in this study had severe and persistent language problems for which they were receiving special education, and the time lag between initial and final testing was relatively short. So maturational change seemed an unlikely explanation for the improvement. However, practice effects were much more plausible.

A practice effect, as its name implies, is when you get better at doing a task simply because of prior exposure to the task. It doesn’t mean you have to explicitly practice doing the task – rather it means that you can learn something useful about the task from previous exposure. A nice illustration of this is a balancing device that came as part of an exercise programme called Wii-fit. This connected with a controller box and the TV, so you could try specific exercises that were shown on the screen. Users were encouraged to start with exercises to estimate their “brain age”. When the first author first tried the exercises, her brain age was estimated around 70 – at the time about 20 years more than her chronological age. But just a few days later, when she tried again, her brain age had improved enormously to be some 5 years younger than her chronological age. How could this be? She had barely begun to use the Wii-fit and so the change could not be attributed to the exercises. Rather, it was that familiarity with the evaluation tasks meant that she understood what she was supposed to do and could respond faster and apply strategies to optimize her performance.

It is often assumed that practice effects don’t apply to psychometric tests, especially those with high test-retest reliability. However, that doesn’t follow. When measured by a correlation coefficient, high reliability just tells you whether the rank ordering of a group of people will be similar from one test occasion to another – it does not say anything about whether the average performance will improve. In fact, we now know that some of our most reliable IQ tests show substantial practice effects persisting over many years e.g., (Rabbitt et al., 2004). One way of attempting to avoid practice effects is to use “parallel forms” of a test – that is different items with the same format. Yet that does not necessarily prevent practice effects, if these depend primarily on familiarization with task format and development of strategies.

There is a simple way to avoid confusing practice effects with genuine intervention effects, and it’s the same solution as for spontaneous improvement – include a control group who don’t receive the intervention. They should show exactly the same practice effects as the treated group, and so provide a comparison against which intervention-related change can be assessed.

5.4 Regression to the mean

Spontaneous improvement and practice effects are relatively easy to grasp intuitively using familiar examples. Regression to the mean is quite different – it appears counter-intuitive to most people and it is frequently misunderstood.

It refers to the phenomenon whereby, if you select a group on the basis of poor scores on a measure, then the worse the performance is at the start, the greater the improvement you can expect on re-testing. The key to understanding regression to the mean is to recognize two conditions that are responsible for it: a) the same measure is used to select cases for the study and to assess their progress and b) the measure has imperfect test-retest reliability.

Perhaps the easiest way to get a grasp of what it entails is to suppose we had a group of 10 people and asked them each to throw a dice 10 times and total the score. Let’s then divide them into the 5 people who got the lowest scores and the 5 who got the highest scores and repeat the experiment. What do we expect? Well, assuming we don’t believe that anything other than chance affects scores (no supernatural forces or “winning streaks”), we’d expect the average score of the low-scorers to improve, and the average score of the high scorers to decline. This is because the most likely outcome for everyone is to get an average score on any one set of dice throws. So if you were below average on time 1, and average on time 2, your score has gone up; if you were above average on time 1, and average on time 2, your score has gone down. So that’s the simplest case, when we have a score that is determined only by chance: i.e. the test-retest reliability of the dice score is zero.

Cognitive test scores are interesting here because they are typically thought of comprising two parts: a “true” score, which reflects how good you really are at whatever is being measured, and an “error” score, which reflects random influences. Suppose, for instance, that you test a child’s reading ability. In practice, the child is a very good reader, in the top 10% for her age, but the exact number of words she gets right will depend on all sorts of things: the particular words selected for the test (she may know “catacomb” but not “pharynx”), the mood she is in on the day, whether she is lucky or unlucky at guessing at words she is uncertain about. All these factors would be implicated in the “error” score, which is treated just like an additional chance factor or throw of the dice affecting a test score. A good test is mostly determined by the “true” score, with only a very small contribution of an “error” score, and we can identify it by the fact that children will be ranked by the test in a very similar way from one test occasion to the next; i.e. there will be good test-retest reliability. In other words, the correlation from time 1 to time 2 will be high.

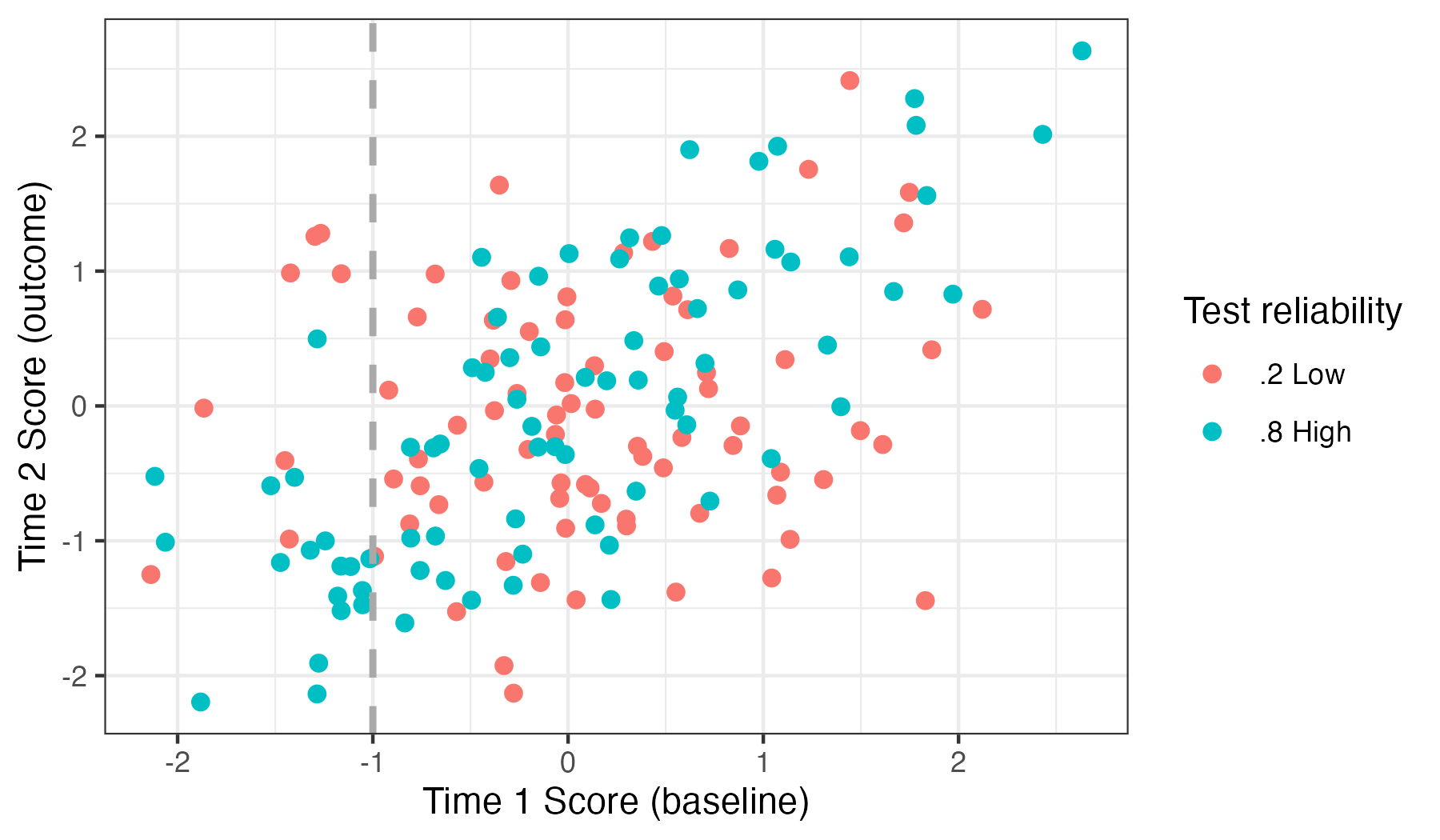

Figure 5.2: Simulated test scores for 160 children on tests varying in reliability. Individuals are colour-coded depending on whether they are given a test of low (.2), or high (.8) test-retest reliability. The simulations assume there is no effect of intervention, maturation or practice

Figure 5.2 shows simulated data for children seen on two occasions, when there is no effect of intervention, maturation or practice. The vertical grey line divides the samples into those who score more than one SD below the mean at time 1. Insofar as chance contributes to their scores, then at time 2, we would expect the average score of such a group to improve, because chance pushes the group average towards the overall mean score. One can see by inspection that those given a low-reliability test tend to have average scores close to zero at time 2; those given a high-reliability test tend to remain below average. For children to the left of the grey vertical line, the mean time 1 scores for the two groups are very similar, but at time 2, the mean scores are 0.23 and -1.16 respectively for the low and high reliability tests.

The key point here is that if we select individuals on the basis of low scores on a test (as is often done, e.g. when identifying children with poor reading scores for a study of a dyslexia treatment), then, unless we have a highly reliable test with a negligible error term, the expectation is that the group’s average score will improve on a second test session, for purely statistical reasons. In general, psychometric tests are designed to have reasonable reliability, but this varies from test to test and is seldom higher than .75-.8.

Cynically, one could say that if you want to persuade the world that you have an effective treatment, just do a study where you select poor performers on a test with low reliability! There is a very good chance you will see a big improvement in their scores on re-test, regardless of what you do in between.

So regression to the mean is a real issue in longitudinal and intervention studies. It is yet another reason why scores will change over time. X. Zhang & Tomblin (2003) noted that we can overcome this problem by using different tests to select cases for an intervention and to measure their outcomes. Or we can take into account regression to the mean by comparing our intervention group to a control group, who will be subject to the same regression to the mean.

5.5 Check your understanding

Identify an intervention study on a topic of interest to you – you could do this by scanning through a journal, or by typing relevant keywords into a database such as Google Scholar, Web of Science or Scopus. If you are not sure how to do this, your librarian should be able to advise. It is important that the published article is available so you can read the detailed account. If an article is behind a paywall, you can usually obtain a copy by emailing the corresponding author.

Your task is to evaluate the article in terms of how well it addresses the systematic biases covered in this chapter. Are the results likely to be affected by spontaneous improvement, practice effects, or regression to the mean? Does the study design control for these? Note that for this exercise you are not required to evaluate the statistical analysis: the answers to these questions depend just on how the study was designed.

A useful explainer for regression to the mean is found at this website: https://www.andifugard.info/regression-to-the-mean/ (Fugard, 2023). It links to an app where you can play with settings of sample size, reliability and sample selection criteria. Load the app and try to predict in advance how the results will be affected as you use the sliders to change the variables.