5 UK Newspaper Data

Most of the available newspaper data in the UK is based on the collections of the British Library (though other libraries do hold significant collections). This is a huge collection, but getting access to it is not straightforward. In a nutshell:

- If you’re happy with a small test dataset, you could use the freely-available Heritage Made Digital titles.

- If you would like to do analysis on something slightly more historically significant or rigorous, you could contact Gale and ask them to supply you with the JISC Historical Newspaper Collection.

- If you really want access to ALL the newspapers from the collection, you’ll have to contact Find My Past.

5.1 British Library Newspapers

The British Library holds about 60 million issues, or 450 million pages of newspapers. They now span over 400 years, but the coverage prior to the nineteenth century is very partial.2 Prior to 1800, the collection has serious gaps, and many issues of many titles have simply not survived. This means that only a fraction of what was published has been preserved or collected, and only a fraction of that which has been collected has been digitised.

It’s actually surprisingly difficult to know exactly what has been digitised, but a rough count is possible, using the ‘newspaper year’ as a unit. This is all the issues for one title, for one year. Its not perfect, because a newspaper-year of a weekly looks the same as a newspaper-year for a daily, but it’s an easy unit to count. There’s currently about 40,000 newspaper-years on the British Newspaper Archive. The entire collection of British and Irish Newspapers is probably, at a guess, about 350,000 newspaper-years.

It’s all very well being able to access the content, but for the purposes of the kind of things we’d like to do, access to the data is needed. The following are the main British Library digitised newspaper sources.

Figure 5.1: An interactive map of the British Library’s physical newspaper collection. Links are to the catalogue entry.

5.2 Burney Collection

The Burney Collection contains about one million pages, from the very earliest newspapers in the seventeenth century to the beginning of the 19th, collected by Rev. Charles Burney in the 18th century, and purchased by the Library in 1818.3 It’s actually a mixture of both Burney’s own collction and stuff inserted since. It was microfilmed in its entirety in the 1970s. As Andrew Prescott has written, ‘our use of the digital resource is still profoundly shaped by the technology and limitations of the microfilm set’4 The collection was imaged in the 90s but because of technological restrictions it wasn’t until 2007 when, with Gale, the British Library released the Burney Collection as a digital resource.

It’s not generally available as a data download, but the raw OCR would be of limited use anyway. OCR for early modern print is not very good, and it was certainly worse ten years ago when the collection was processed. The accuracy of the OCR has been measured, and one report found that the ocr for the Burney newspapers offered character accuracy of 75.6% and word accuracy of 65%..5

However, this is still a useful collection for browsing and keyword searching, which can usually be accessed through an institutional subscription to Gale, packaged as .

5.3 JISC Newspaper digitisation projects

Most of the projects in the UK which have used newspaper data, from the Political Meetings Mapper, to the Victorian Meme Machine have used the British Library’s 19th Century Newspapers collection. It’s not publically available, but many academics have requested a copy of the data from Gale, or used it on-site at the British Library, where it is available as a dataset.

The collection can be mapped using its metadata.

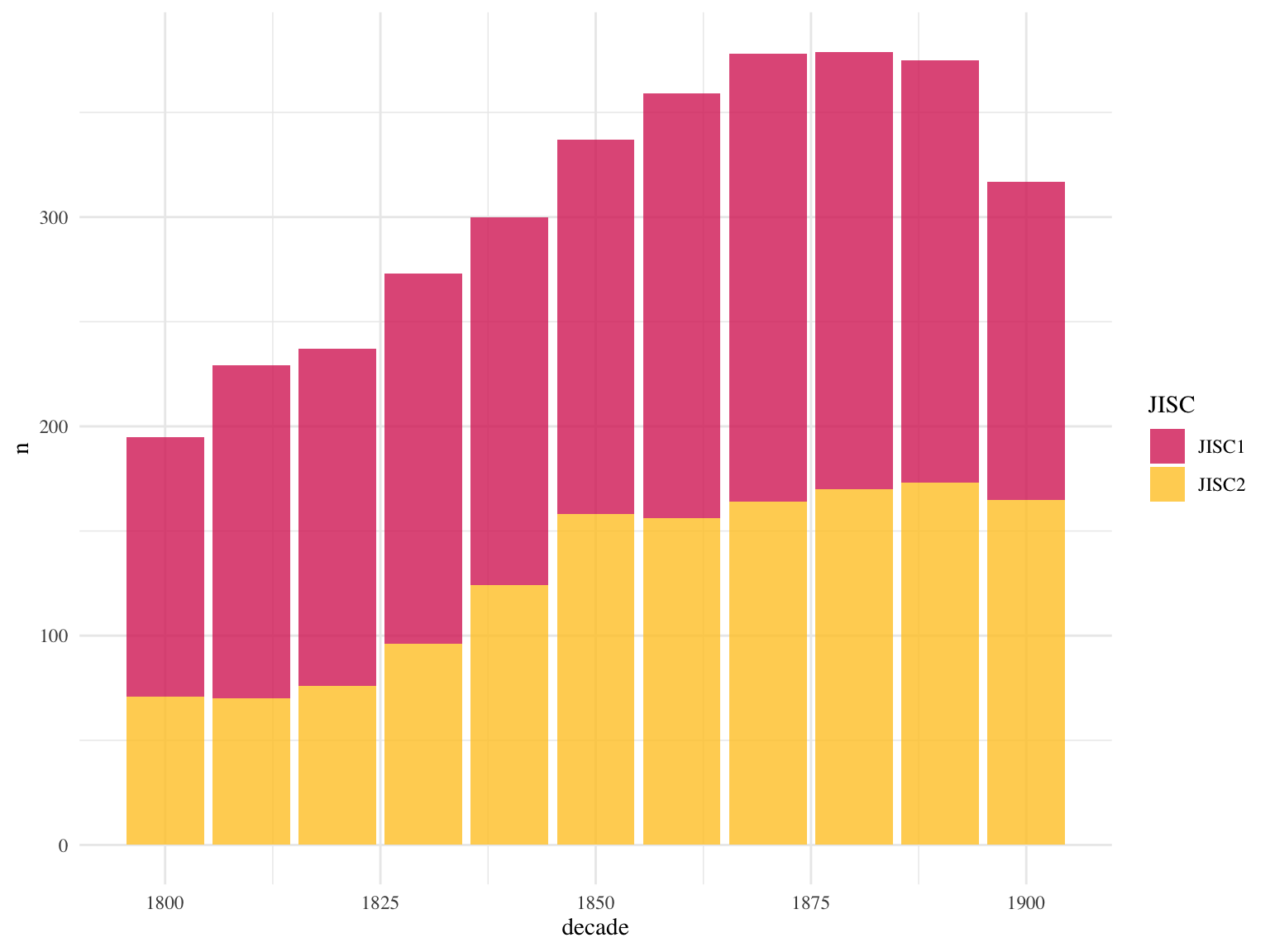

Figure 5.2: Very approximate chart of JISC titles, assuming that we had complete runs for all. Counted by year rather than number of pages digitised.

The JISC newspaper digitisation program began in 2004, when The British Library received two million pounds from the Joint Information Systems Committee (JISC) to complete a newspaper digitisation project. A plan was made to digitise up to two million pages, across 49 titles.6 A second phase of the project digitised a further 22 titles.7

The titles cover England, Scotland, Wales and Ireland, and it should be noted that the latter is underrepresented although it was obviously an integral part of the United Kingdom at the time of the publication of these newspapers - something that’s often overlooked in projects using the JISC data. They cover about 40 cities ??, and are spread across 24 counties within Great Britain ??, plus Dublin and Belfast. It’s useful quoting Ed King in full on this:

The forty-eight titles chosen represent a very large cross-section of 19th century press and publishing history. Three principles guided the work of the selection panel: firstly, that newspapers from all over the UK would be represented in the database; in practice, this meant selecting a significant regional or city title, from a large number of potential candidate titles. Secondly, the whole of the nineteenth century would be covered; and thirdly, that, once a newspaper title was selected, all of the issues available at the British Library would be digitised. To maximise content, only the last timed edition was digitised. No variant editions were included. Thirdly, once a newspaper was selected, all of its run of issue would be digitised.8

Jane Shaw wrote, in 2007:

The academic panel made their selection using the following eligibility criteria:

To ensure that complete runs of newspapers are scanned To have the most complete date range, 1800-1900, covered by the titles selected To have the greatest UK-wide coverage as possible To include the specialist area of Chartism (many of which are short runs) To consider the coverage of the title: e.g., the London area; a large urban area (e.g., Birmingham); a larger regional/rural area To consider the numbers printed - a large circulation The paper was successful in its time via its sales To consider the different editions for dailies and weeklies and their importance for article inclusion or exclusion To consider special content, e.g., the newspaper espoused a certain political viewpoint (radical/conservative) The paper was influential via its editorials.9

The result was a heavily curated collection, albeit with decent academic rigour and good intentions and like all collections created in this way, it is subject, quite rightly, to a lot of scrutiny by historians.10

This is all covered in lots of detail elsewhere, including some really interesting critiques of the access and so forth.11 But the overall makeup of it is clear, and this was a very specifically curated collection, though it was also influenced by contingency, in that it used microfilm (sometimes new microfilm). But overall, one might say that the collection has specific historical relevant, and was in ways representative.

It does, though, only represent a tiny fraction of the newspaper collection, and by being relevant and restricted to ‘important’ titles, it does of course miss other voices. For example, much of the Library’s collection consists of short runs, and much of it has not been microfilmed, which means it won’t have been selected for digitisation. This means that 2019 digitisation selection policies are indirectly greatly influenced by microfilm selection policies of the 70s, 80s, and 90s. Subsequent digitisation projects are trying to rectify these motivations, but again, it’s good to keep in mind the

## Warning in is.na(values): is.na() applied to non-(list or vector) of type

## 'closure'## Warning in validateCoords(lng, lat, funcName): Data contains 1 rows with either

## missing or invalid lat/lon values and will be ignoredFigure 5.3: Interactive map of the JISC Newspapers

Currently researchers access this either through Gale, or through the British Library as an external researcher. Many researchers have requested access to the collection through Gale, which they will apparently do in exchange for a fee for the costs of the hard drives and presumably some labour time. The specifics of the XML used, and some code for extracting the data, are available in the following chapter.

5.4 British Newspaper Archive

Most of the British Library’s digitised newspaper collection is available on the British Newspaper Archive (BNA). The BNA is a commercial product run by a family history company called FindMyPast. FindMyPast is now responsible for digitising large amounts of the Library’s newspapers, mostly through microfilm. As such, they have a very different focus to the JISC digitisation projects. The BNA is constantly growing, and it already dwarfs the JISC projects by number of pages: the BNA currently hosts about 46 million pages, against the 3 million or so of the two JISC projects 5.4. Sadly, there is little provision made for data access, or even institutional subscriptions for researchers.

What it means is that most data-driven historical work carried out on newspapers has used the JISC data, rather than the much larger BNA collection, because of relative ease-of-access. There are some exceptions: the used the BNA data, processing the top phrases and words from about 16 million pages. The collection has doubled in size since then: it’s likely that were it to be run again the results would be different.

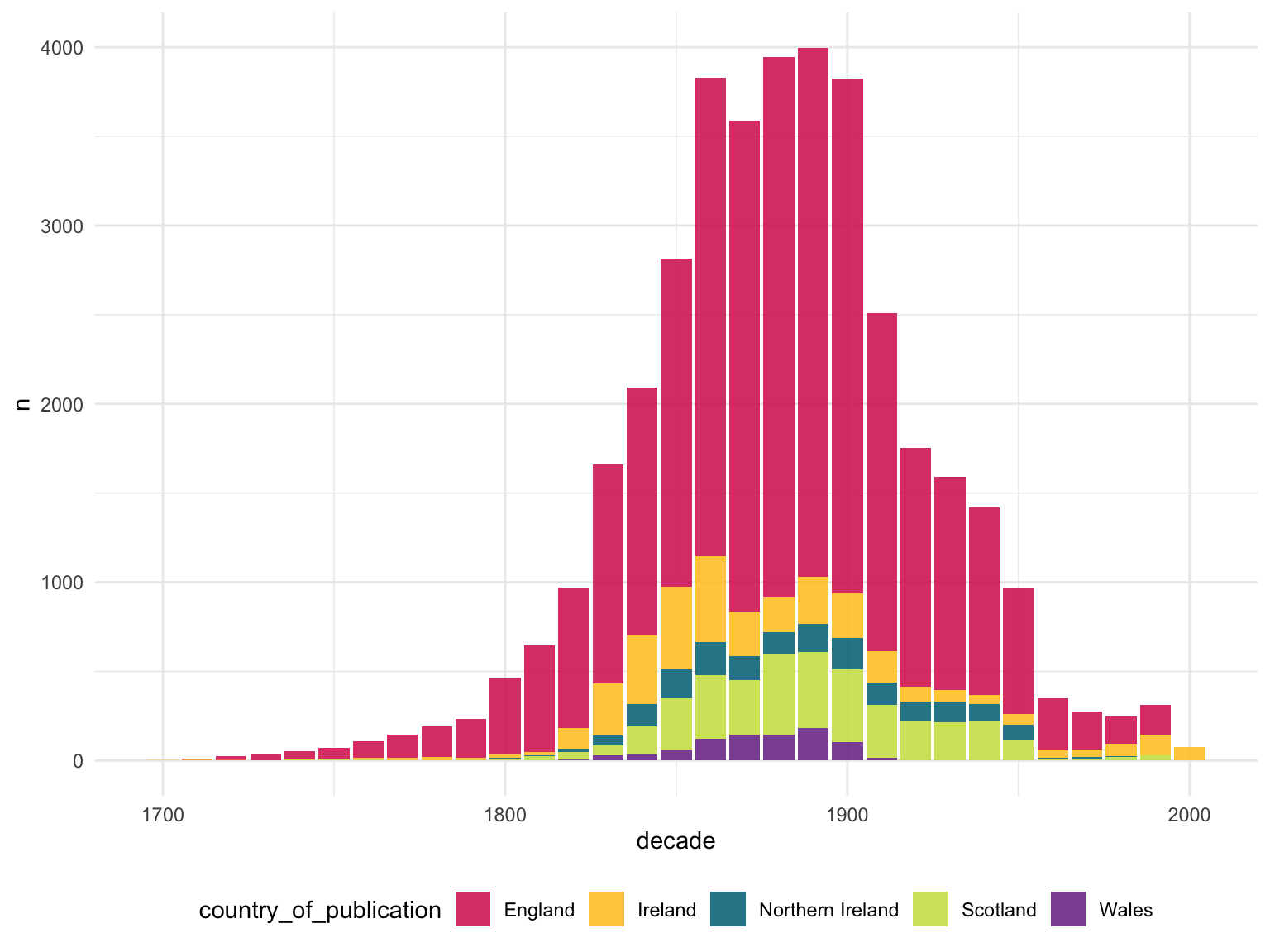

Figure 5.4: Newspaper-years on the British Newspaper Archive. Note that this includes JISC content above.

![Titles on the British Newspaper Archive.^[data from https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/titles/]](_main_files/figure-html/bna-titles-map-1.png)

Figure 5.5: Titles on the British Newspaper Archive.12

5.5 British Library Openly available newspaper data - Heritage Made Digital

The good news is that there is at least some raw British Library newspaper data available as a direct, free download, through the Heritage Made Digital project. This is a project within the British Library to digitise up to 1.3 million pages of 19th century newspapers. It has a specific curatorial focus: it picked titles which are completely out of copyright, which means that they all finished publication before 1879. It also had preservation aims: because of this, it chose titles which were not on microfilm, and were also in poor or unfit condition. Newspaper volumes in unfit condition cannot be called up by readers: this meant that if a volume is not microfilmed and is in this state, it can’t be read by anyone. There’s some more about the project available here: https://blogs.bl.uk/thenewsroom/2019/01/heritage-made-digital-the-newspapers.html

The other curatorial goal was to focus on ‘national’ titles. In practice this meant choosing titles printed in London, but without a specific London focus. The JISC digitisation projects focused on regional titles, then local, and all the ‘big’ nationals like the Times or the Manchester Guardian have been digitised by their current owners. This means that a bunch of historically important titles may have fallen through the cracks, and this projects is digitising some of those.13

The good news is that as these newspapers are deemed out of copyright, the text data can be made freely downloadable. Currently the first batch of newspapers, in METS/ALTO format, are available on the British Library’s Open Repository. They have a CC-0 licence, which means they can be used for any purpose whatsoever. The code examples in the following chapters will use this data, and chapter six will show you how to download the titles using a bulk downloader, instead of going through them one-by-one.

The titles are currently contained within a collection item on the repository called British Library News Datasets. Each title has been uploaded as a separate repository dataset, with its own DOI. Within each dataset, each year of the title is available as a separate zip file.

Current the repository contains the following titles. Some titles are a ‘standard’ title for a newspaper which went through several changes in name. Some are missing individual years within the range here:

- The Express from 1846-1868.

- The Press from 1853-1858

- The Star from 1801-1831

- The National Register from 1808-1823

- The Statesman from 1806-1824

- The British Press; or, Morning Literary Advertiser from 1803-1826

- The Sun

- The Liverpool Standard etc

- Coloured News from 1855

- The Northern Daily Times etc

5.6 Other data sources

There are a number of really useful metadata files available through the British Library research repository. First of all, a title-level list of all British and Irish Newspapers held by the library, available here, and most recently, two digitised press directories, available here and here. All of these are have a Public Domain licence.

5.7 What access do you need?

You want to find individual articles for historical research? Most likely you’ll want to access to either the British Newspaper Archive, or Gale Historical Newspapers. The coverage in the former is MUCH bigger, but they don’t do institutional subscriptions, whereas you might be able to access the Gale newspapers for free through your university or Library.

You want to do some text mining, maybe for testing or teaching, and you’re not so bothered about having full coverage The Heritage Made Digital datasets might be useful for you, see the description above.

You want to do text mining on a large corpus There’s a number of ways that researchers have got access to large datasets of newspaper text. One option is to contact British Library Labs, who have arranged access to datasets which are not openly available. A second option is to contact Gale, who have in the past provided the data for their ‘Historical Newspapers’ collection to researchers.

You want to do text mining on the entire digitised collection I would advise speaking to Find My Past directly, who run the British Newspaper Archive. They do take requests for access. There is a dataset of n-grams which has been used for text mining, sentiment analysis etc. and might be useful, though the collection has grown significantly since this point. It’s available as a free download from here: https://doi.org/10.5523/bris.dobuvuu00mh51q773bo8ybkdz

You want to do something involving the images, such as computer vision techniques You’ll probably need to request access to newspapers through the British Library, or through Gale. Gale have sent a copy of the JISC 1 & 2 data (with OCR enhancements) on a hard drive to researchers, for a fee. Access through the Library will allow for image analysis but might be difficult to take away. The images up to 1878 are cleared for reuse.

Ed King, ‘Digitisation of British Newspapers 1800-1900,’ 2007 <https://www.gale.com/intl/essays/ed-king-digitisation-of-british-newspapers-1800-1900> [accessed 2007].↩︎

Andrew Prescott, ‘Travelling Chronicles: News and Newspapers from the Early Modern Period to the Eighteenth Century,’ ed. by Siv Gøril Brandtzæg, Paul Goring, and Christine Watson (Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill, 2018), pp. 51–71.↩︎

Prescott.↩︎

Prescott.↩︎

King.↩︎

Jane Shaw, ‘Selection of Newspapers,’ British Library Newspapers, 2007 <https://www.gale.com/intl/essays/jane-shaw-selection-of-newspapers>; Jane Shaw, ‘10 Billion Words: The British Library British Newspapers 1800-1900 Project: Some Guidelines for Large-Scale Newspaper Digitisation,’ 2005 <https://archive.ifla.org/IV/ifla71/papers/154e-Shaw.pdf> for a good brief overview to the selection process for JISC 1.↩︎

Ed King, ‘British Library Digitisation: Access and Copyright,’ 2008.↩︎

Shaw.↩︎

Paul Fyfe, ‘An Archaeology of Victorian Newspapers,’ Victorian Periodicals Review, 49.4 (2016), 546–77 <https://doi.org/10.1353/vpr.2016.0039> for example.↩︎

Thomas Smits, ‘Making the News National: Using Digitized Newspapers to Study the Distribution of the Queen’s Speech by W. H. Smith & Son, 1846–1858,’ Victorian Periodicals Review, 49.4 (2016), 598–625 <https://doi.org/10.1353/vpr.2016.0041>; James Mussell, ‘Elemental Forms: Elemental Forms: The Newspaper as Popular Genre in the Nineteenth Century,’ Media History, 20.1 (2014), 4–20 <https://doi.org/10.1080/13688804.2014.880264> both include some discussion and critique of the British Library Newspaper Collection.↩︎

data from https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/titles/↩︎

The term national is debatable, but it’s been used to try and distinguish from titles which clearly had a focus on one region. Even this is difficult: regionals would have often had a national focus, and were in any case reprinting many national stories. But their audience would have been primarily in a limited geographical area, unlike a bunch of London-based titles, which were printed and sent out across the country, first by train, then the stories themselves by telegraph.↩︎