Chapter 11 False positives, p-hacking and multiple comparisons

11.1 Type I error

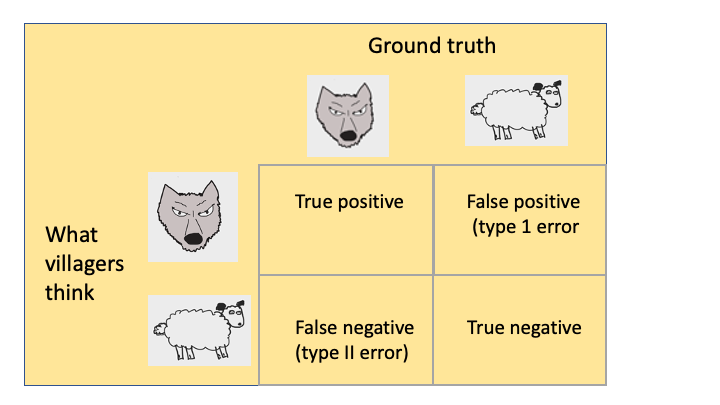

A Type I error is a false positive, which occurs when the null hypothesis is rejected but a true effect is not actually present. This would correspond to the situation where the evidence seems to indicate an intervention is effective, but in reality it is not. One useful mnemonic for distinguishing Type I and Type II errors is to think of the sequence of events in the fable of the boy who cried wolf. This boy lived in a remote village and he used to have fun running out to the farmers in the fields and shouting “Wolf! Wolf!” and watching them all get alarmed. The farmers were making an (understandable) Type I error, of concluding there was a wolf when in fact there was none. One day, however, a wolf turned up. The boy ran into the village shouting “Wolf! Wolf!” but nobody took any notice of him, because they were used to his tricks. Sadly, all the sheep got eaten because the villagers had made a Type II error, assuming there was no wolf when there really was one. This figure is really the same as Table 10.1 from the previous chapter, but redrawn in terms of wolves and sheep.

The type I error rate is controlled by setting the significance criterion, \(\alpha=0.05\), at 5%, or sometimes more conservatively 1% (\(\alpha=0.01\)). With \(\alpha=0.05\), on average 1 in 20 statistically significant results will be false positives; when it is .01, then 1 in 100 will be false positives. The .05 cutoff is essentially arbitrary, but very widely adopted in the medical and social sciences literature, though debate continues as to whether a different convention should be adopted Lakens et al. (2018).

11.2 Reasons for false positives

There is one obvious reason why researchers get false positive results: chance. It follows from the definition given above that if you adopt an alpha level of .05, and if the treatment really has no effect, you will wrongly conclude that your intervention is effective in 1 in 20 studies. This is why we should never put strong confidence in, or introduce major policy changes on the basis of, a single study. The probability of getting a false positive once is .05, but if you replicate your finding, then it is far more likely that it is reliable - the probability of two false positives in a row is .05 * .05 = .0025, or 1 in 400.

Unfortunately, though, false positives and non-replicable results are far more common in the literature than they should be if our scientific method was working properly. One reason, which will be covered in Chapter 19, is publication bias. Quite simply, there is a huge bias in favour of publishing papers reporting statistically significant results, with null results getting quietly forgotten.

A related reason is a selective focus on positive findings within a study. Consider a study where the researcher measures children’s skills on five different measures, comprehension, expression, mathematics, reading, and motor skills, but only one of them, comprehension, shows a statistically significant improvement (p < .05) after intervention that involves general “learning stimulation”. It may seem reasonable to delete the other measures from the write-up, because they are uninteresting. Alternatively, the researcher may report all the results, but argue that there is a good reason why the intervention worked for this specific measure. Unfortunately, this would be badly misleading, because the statistical test needed for a study with five outcome measures is different from the one needed for a single measure. Failure to understand this point is widespread - insofar as it is recognized as a problem, it is thought of as a relatively minor issue. Let’s look at this example in more detail to illustrate why it can be serious.

We assume in the example above that the researcher would have been equally likely to single out any one of the five measures, provided it gave p < .05, regardless of which one it was; with hindsight, it’s usually possible to tell a good story about why the intervention was specifically effective with that task. If that is so, then interpreting a p-value for each individual measure is inappropriate, because the implicit hypothesis that is being tested is “do any of these measures improve after intervention?”. The probability of a false positive for any specific measure is 1 in 20, but the probability that at least one measure gives a false positive result is higher. We can work it out as follows. Let’s start by assuming that in reality the intervention has no effect:

- With \(\alpha\) set to. 05, the probability that any one measure gives a nonsignificant result = .95.

- The probability that all five measures give a nonsignificant result is found by multiplying the probabilities for the five tasks: .95 * .95 * .95 * .95 * .95 = .77.

- So it follows that the probability that at least one measure gives a significant result (p-value < .05) is 1-.77 = .23.

In other words, with five measures to consider, the probability that at least one of them will give us p < .05 is not 1 in 20 but 1 in 4. The more measures there are, the worse it gets. We will discuss solutions to this issue below (see Multiple testing).

Psychologists have developed a term to talk about the increase in false positives that arises when people pick out results on the basis that they have a p-value of .05, regardless of the context - p-hacking (Simonsohn et al., 2014). Bishop & Thompson (2016) coined the term ghost variable to refer to a variable that was measured but was then not reported because it did not give significant results - making it impossible to tell that p-hacking had occurred. Another term, HARKing, or “hypothesising after the results are known” (Kerr, 1998) is used to describe the tendency to rewrite not just the Discussion but also the Introduction of a paper to fit the result that has been obtained. Sadly, many researchers don’t realize that these behaviours can dramatically increase the rate of false positives in the literature. Furthermore, they may be encouraged by senior figures to adopt exactly these practices: a notorious example is that of Bem (2004). Perhaps the most common error is to regard a p-value as a kind of inherent property of a result that reflects its importance regardless of context. In fact, context is absolutely key: a single p-value below .05 has a very different meaning in a study where you only had one outcome measure than in a study where you tested several measures in case any of them gave an interesting result.

A related point is that you should never generate and test a hypothesis using the same data. After you have run your study, you may be enthusiastic about doing further research with a specific focus on the comprehension outcome measure. That’s fine, and in a new study with specific predictions about comprehension you could adopt \(\alpha\) of .05 without any corrections for multiple testing. Problems arise when you subtly change your hypothesis after seeing the data from “Do any of these N measures show interesting results?” to “Does comprehension improve after intervention?”, and apply statistics as if the other measures had not been considered.

In clinical trials research, potential for p-hacking is in theory limited by a requirement for registration of trial protocols, which usually entails that a primary outcome measure is identified before the study is started (see Chapter 20). This has not yet become standard for behavioural interventions, and in practice, clinical trial researchers often deviate from the protocol after seeing the results (Goldacre et al., 2019). It is important to be aware of the potential for a high rate of false positives when multiple outcomes are included.

Does this mean that only a single outcome can be included? The answer is no: It might be the case that the researcher requires multiple outcomes to determine the effectiveness of an intervention, for example, a quantity of interest might not be able to be measured directly, so several proxy measures are recorded to provide a composite outcome measure. But in this case, it is important to plan in advance how to conduct the analysis to avoid an increased rate of false positives.

Selection of one measure from among many is just one form of p-hacking. Another common practice has been referred to as the “garden of forking paths”: the practice of trying many different analyses, including making subgroups, changing how variables are categorized, excluding certain participants post hoc, or applying different statistical tests, in the quest for something significant. This has all the problems noted above in the case of selecting from multiple measures, except it is even harder to make adjustments to the analysis to take it into account because it is often unclear exactly how many different analyses could potentially have been run. With enough analyses it is almost always possible to find something that achieves the magic cutoff of p < .05.

This animation tracks how the probability of a “significant” p-value below .05 increases as one does increasingly refined analyses of hypothetical data investigating a link between handedness and ADHD - with data split according to age, type of handedness test, gender, and whether the child’s home is rural or urban. The probability of finding at least one significant result is tracked at the bottom of the display. For each binary split, the number of potential contrasts doubles, so at the end of the path there are 16 potential tests that could have been run, and the probability of at at least one “significant” result in one combination of conditions is .56. The researcher may see that a p-value is below .05 and gleefully report that they have discovered an exciting association, but if they were looking for any combination of values out of numerous possibilities, then the p-value is highly misleading - in particular, it is not the case that there is only a 1 in 20 chance of obtaining a result this extreme.

There are several ways we can defend ourselves against a proliferation of false positives that results if we are too flexible in data analysis:

Pre-registration of the study protocol, giving sufficient detail of measures and planned analyses to prevent flexible analysis - or at least make it clear when researchers have departed from the protocol. We cover pre-registration in more detail in Chapter 20.

Using statistical methods to correct for multiple testing. Specific methods are discussed below. Note, however, that this is only effective if we correct for all the possible analyses that were considered.

“Multiverse analysis”: explicitly conducting all possible analyses to test how particular analytic decisions affected results. This is beyond the scope of this book, as it is more commonly adopted in non-intervention research contexts (Steegen et al., 2016) when analysis of associations between variables is done with pre-existing data sets.

11.3 Adjusting statistics for multiple testing

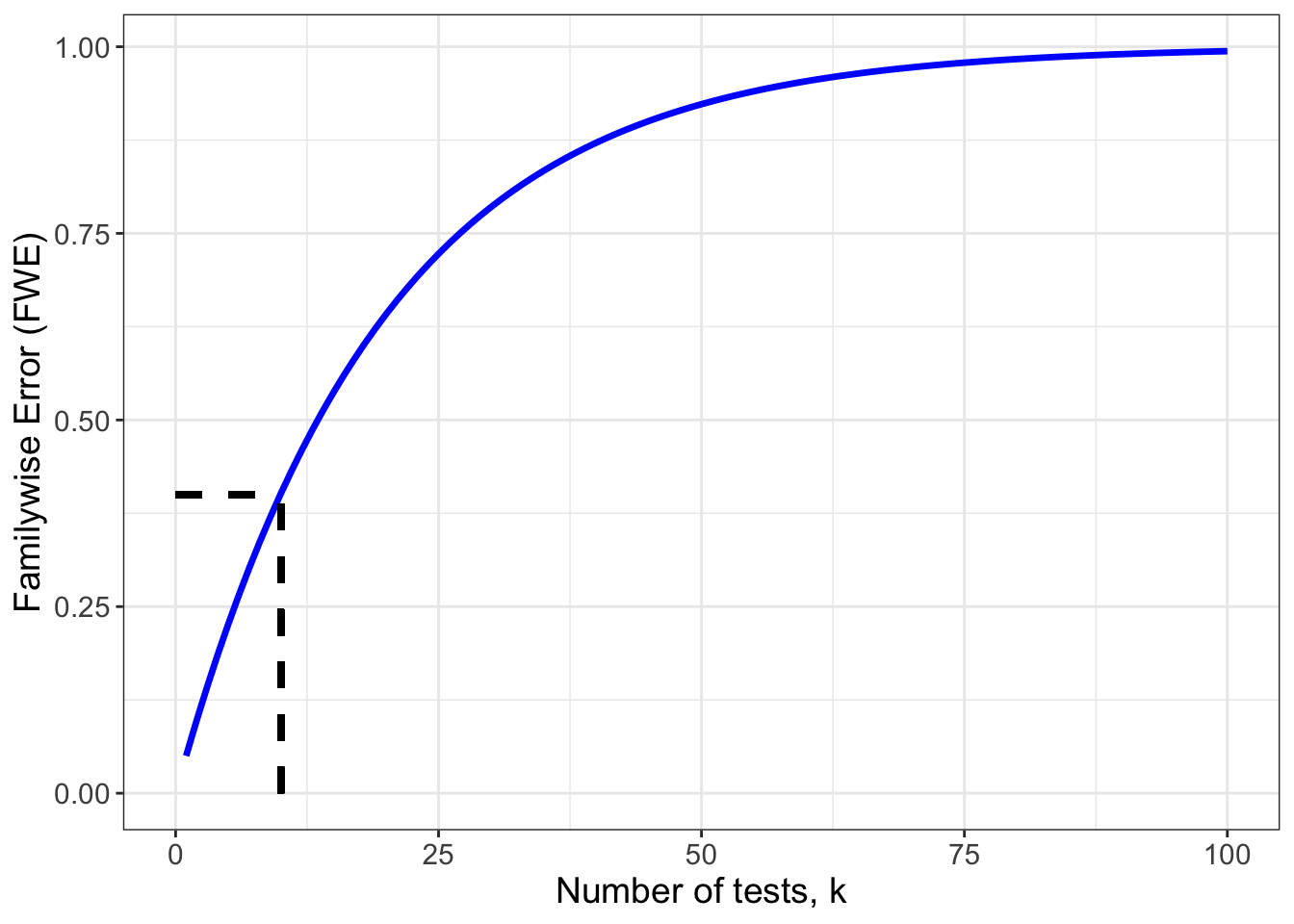

As noted above, even when we have a well-designed and adequately powered study, if we collect multiple outcome variables, or if we are applying multiple tests to the same data, then we increase our chance of finding a false positive. Remember that if we set \(\alpha\) to .05 and apply \(k\) tests to our data, then the probability of finding at least one false positive is given by \(1-(1-\alpha)^{k}\). This is officially known as the family-wise error rate (FWER).

Figure 11.1: Plot of relationship between familywse error rate and number of statistical tests

Figure 11.1 shows the relationship between the familywise error rate and the number of tests conducted on the data. Note that the left-most point of the blue line corresponds to the case when we have just one statistical test, and the probability of a false positive is .05, exactly where we would expect. The dotted line shows the case where we performed 10 tests (k = 10), increasing our chance of obtaining a false positive to approximately 40%. Clearly, the more tests applied, the greater the increase in the chance of at least one false positive result. Although it may seem implausible that anyone would conduct 100 tests, the number of implicit tests can rapidly increase if sequential analytic decisions multiply, as shown in the Garden of Forking Paths example, where we subdivided the analysis 4 times, to give 2^4 = 16 possible ways of dividing up the data.

There are many different ways to adjust for the multiple testing in practice. We shall discuss some relatively simple approaches that are useful in the context of intervention research, two of which can be used when evaluating published studies, as well as when planning a new study.

11.3.1 Bonferroni Correction

The Bonferroni correction is both the simplest and most popular adjustment for multiple testing. The test is described as “protecting the type I error rate”, i.e. if you want to make a false positive error only 1 in 20 studies, the Bonferroni correction specifies a new \(\alpha\) level that is adjusted for the number of tests. The Bonferroni correction is very easy to apply: you just divide your desired false positive rate by the number of tests conducted.

For example, say we had some data and wanted to run multiple t-tests between two groups on 10 outcomes, and keep the false positive rate at 1 in 20. The Bonferroni correction would adjust the \(\alpha\) level to be 0.05/10 = 0.005, which would indicate that the true false positive rate would be \(1-(1-\alpha_{adjusted})^{n} = 1-(1-0.005)^{10} = 0.049\) which approximates our desired false positive rate. So we now treat any p-values greater than .005 as non-significant. This successfully controls our type I error rate at approximately 5%.

It is not uncommon for researchers to report results both with and without Bonferroni correction - using phrases such as “the difference was significant but did not survive Bonferroni correction”. This indicates misunderstanding of the statistics. The Bonferroni correction is not some kind of optional extra in an analysis that is just there to satisfy pernickety statisticians. If it is needed - as will be the case when multiple tests are conducted in the absence of clear a priori predictions - then the raw uncorrected p-values are not meaningful, and should not be reported.

The Bonferroni correction is widely used due to its simplicity but it can be over-conservative when our outcome measures are correlated. We next consider another approach, MEff, that takes correlation between measures into account.

11.3.2 MEff

The MEff statistic was developed in the field of genetics by Cheverud (2001). It is similar to the Bonferroni correction, except that instead of dividing the alpha level by the number of measures, it is divided by the effective number of measures, after taking into account the correlation between them. To understand how this works, consider the (unrealistic) situation when you have 5 measures but they are incredibly similar, with an average intercorrelation of .9. In that situation, they would act more like a single measure, and the effective number of variables would be close to 1. If the measures were totally uncorrelated (with average intercorrelation of 0), then the effective number of measures would be the same as the actual number of measures, 5, and so we would use the regular Bonferroni correction. In practice, the number of effective measures, Meff, can be calculated using a statistic called the eigenvalue that reflects the strength of correlation between measures. A useful tutorial for computing MEff is provided by Derringer (2018).

Bishop (2023) provided a lookup table of modified alpha levels based on MEff according to the average correlation between sets of outcome measures. Part of this table is reproduced here as Table 11.1.

| Average.r | N2 | N4 | N6 | N8 | N10 | N12 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.0 | 0.025 | 0.013 | 0.008 | 0.006 | 0.005 | 0.004 |

| 0.1 | 0.025 | 0.013 | 0.008 | 0.006 | 0.005 | 0.004 |

| 0.2 | 0.026 | 0.013 | 0.009 | 0.006 | 0.005 | 0.004 |

| 0.3 | 0.026 | 0.013 | 0.009 | 0.007 | 0.005 | 0.005 |

| 0.4 | 0.027 | 0.014 | 0.010 | 0.007 | 0.006 | 0.005 |

| 0.5 | 0.029 | 0.015 | 0.011 | 0.008 | 0.006 | 0.005 |

| 0.6 | 0.030 | 0.017 | 0.012 | 0.009 | 0.007 | 0.006 |

| 0.7 | 0.033 | 0.020 | 0.014 | 0.011 | 0.009 | 0.008 |

| 0.8 | 0.037 | 0.024 | 0.018 | 0.014 | 0.012 | 0.010 |

| 0.9 | 0.042 | 0.032 | 0.026 | 0.021 | 0.018 | 0.016 |

| 1.0 | 0.050 | 0.050 | 0.050 | 0.050 | 0.050 | 0.050 |

This table might be useful when evaluating published studies that have not adequately corrected for multiple outcomes, provided one can estimate the degree of intercorrelation between measures.

11.3.3 Extracting a principal component from a set of measures

Where different outcome measures are regarded as indicators of a single underlying factor, the most effective way of balancing the risks of false positive and false negatives may be to extract a single factor from the measures, using a method such as principal component analysis. As there is just one outcome in the analysis, the alpha level does not need to be modified. Bishop (2023) used simulations to consider how statistical power was affected for a range of different effect sizes and correlations between outcomes. In most situations, power increased as more outcomes were entered into a principal component analysis (PCA), even when the correlation between outcomes was low. This makes sense, because when a single component is extracted, the resulting measure will be more reliable than the individual measures that contribute to it, and so the “noise” is reduced, making it easier to see the effect. However, unless one has the original raw data, it is not possible to apply PCA to published results. Also, the increased power of PCA is only found if the set of outcome measures can be regarded as having an underlying process in common. If there are multiple outcome measures from different domains, then MEff is preferable.

11.3.4 Improving power by use of multiple outcomes

Bishop (2023) noted that use of multiple outcome measures can be one way of improving statistical power of an intervention study. It is, however, crucial to apply appropriate statistical corrections such as Bonferroni, Principal Component Analysis or MEff to avoid inflating the false positive rate, and it is also important to think carefully about the choice of measures: are they regarded as different indices of the same construct, or measures of different constructs that might be impacted by the intervention (see Bishop (2023) for further discussion).

11.4 Class exercise

This web-based app by Schönbrodt (2016) allows you to see how easy it can be to get a “significant” result by using flexible analyses. The term DV refers to “dependent variable”, i.e. an outcome measure.

- Set the True Effect slider to its default position of zero, which means that the Null Hypothesis is true - there is no true effect.

- Set the Number of DVs set to 2.

- Press “Run new experiment”.

- The display of results selects the variable with the lowest p-value and highlights it in green. It also shows results for the average of the variables, as DV_all.

- Try hitting Run new experiment 20 times, and keep a tally of how often you get a p-value less than .05. With only two DVs, things are not so bad - on average you’ll get two such values in 20 runs (though you may get more or less than this - if you are really keen, you could keep going for 100 runs to get a more stable estimate of the false positives).

- Now set the number of DVs to 10 and repeat the exercise. You will probably run out of fingers on one hand to count the number of significant p-values.

Felix Schönbrodt, who devised this website, allows you to go even further with p-hacking, showing how easy it is to nudge results into significance by using covariates (e.g. adjusting for age, SES, etc) or by excluding outliers.

Note that if you enjoy playing with p-hacker, you can also use the app to improve your statistical intuitions about sample size and power. The app doesn’t allow you to specify the case where there is only one outcome measure, which is what we really need in this case, so you have to just ignore all but one of the DVs. We suggest you just look at results for DV1. This time we’ll assume you have a real effect. You can use the slider on True Effect to pick a value of Cohen’s d, and you can also select the number of participants in each group. When you Run new experiment, you will find that it is difficult to get a p-value below .05 if the true effect is small and/or the sample size is small, whereas with a large sample and a big effect, a significant result is highly likely.