Chapter 21 Reviewing the literature before you start

A research report typically starts with an Introduction that reviews relevant literature to provide context for the current study. It should establish what work has been done before on this topic, how much we already know, and what gaps there are in our knowledge. The primary focus of any literature review is to survey the research landscape and use this bigger picture outlook to better frame the research question of interest. The literature review may also identify methodological limitations of previous studies that can be addressed in a new study.

It may seem strange to have a chapter on the literature review at the end of this book, but there is a good reason for that. It’s certainly not the case that we think you should only consider the Introduction only after doing the study - although that’s not unknown, especially if the researcher is trying to argue for an interpretation that was not considered in advance (see HARKing, Chapter 11). Rather, it is because in order to write a good Introduction, you first need to understand a lot about experimental design and the biases that can affect research, in order to evaluate the literature properly.

Unfortunately, as noted in Chapter 19, many researchers are not objective in how they review prior literature, typically showing bias in favour of work that supports their own viewpoint. In addition, we often see distortions creeping in whereby studies are cited in a misleading fashion, omitting or de-emphasising inconvenient results. The “spin” referred to in Chapter 19 is not only applied to authors in reporting their own work: it also is seen when researchers cite the work of others.

If we accept that science should be cumulative, it is important not to disregard work that reports results that are ambiguous or inconsistent with our position, but we are often victims of our own cognitive biases that encourage us to disregard inconvenient facts (Bishop, 2020).

Sometimes, a failure to take note of prior work can lead to wasted research funds, as when studies are designed to address questions to which the answer is already known (Chalmers et al., 2014). In the field of speech and language therapy, where there is a shortage of published intervention research, this is unlikely to be so much of a problem. Law et al. (2003) attempted to carry out a meta-analysis to evaluate the effectiveness of intervention for children with developmental speech and language delay/disorder. Over a 25 year period, they found only 25 articles with randomized controlled designs that provided sufficient information for inclusion in a meta-analysis, and the interventions used in these were quite disparate, making it difficult to combine results in a meta-analysis. Although there has been some progress in the past two decades, intervention reports in this field are still fairly rare, and few interventions could be regarded as having such a solid body of evidence in support that further studies are unnecessary. Nevertheless, it is important to take into account prior literature when planning an intervention study, yet, as Chalmers et al. (2014) noted, this is often not done.

We will start by looking at the properties of a systematic review, which is regarded as the gold standard for reviewing work in the field of health interventions.

21.1 What is a systematic review?

In clinical research, a strict definition of a systematic review is provided by the Cochrane collaboration:

A systematic review attempts to identify, appraise and synthesize all the empirical evidence that meets pre-specified eligibility criteria to answer a specific research question. Researchers conducting systematic reviews use explicit, systematic methods that are selected with a view aimed at minimizing bias, to produce more reliable findings to inform decision making. - (Higgins et al., Cochrane, 2021)

The most important part of this definition is the requirement for “pre-specified eligibility criteria”. In practice, many reviews that are badged as “systematic” do not conform to this requirement (Higgins et al., Cochrane, 2021). If a strict protocol is followed this allows the review to be replicated or updated for a different time period. The protocol can be defined and pre-registered (see Chapter 20) and then referred to in the final published systematic review. This ensures the replicability of the review and ensures that search terms are fixed (or, in the case that search terms need to be adjusted, this can be done transparently in the write up).

Performing a systematic review according to Cochrane standards requires a group of authors in order to reduce one source of potential bias, the tendency to interpret criteria for inclusion or evaluation of studies subjectively. The level of detailed required in specifying a protocol is considerable, and the time taken to complete a systematic review can be two years or more after the publication of a protocol, making this approach unfeasible for those with limited resources or time. In the field of speech and language therapy, a review of a specific intervention is unlikely to be this demanding, simply because the intervention literature is relatively small, but even so, the requirement for multiple authors may be impossible to meet, and other requirements can be onerous.

Just as with designing an intervention study, we feel that when planning a literature review, the best should not be the enemy of the good. Or as Confucius is reported to have said: “Better a diamond with a flaw than a pebble without.” We can benefit from considering the Cochrane guidelines for a systematic review, many of which can be adopted when reviewing even a small and heterogeneous literature in order to help guard against bias. However, the guidelines, though clearly written, can be daunting because they have evolved over many years to take into account numerous considerations.

A key point is that the Cochrane advice is written to provide guidelines for those who are planning a stand-alone review that will become part of the Cochrane database. That will not be the aim of most of those reading this book: rather, the goal is to ensure that the literature review for the introduction to a study is not distorted by the usual kinds of bias that were described in Chapter 19.

Accordingly, we provide a simple summary below, adapted for this purpose. We focus on a subset of criteria used in systematic reviews, and recommend that if these can be incorporated in a study, this will make for stronger science than the more traditional style of review in which there is no control over subjective selection or interpretation of studies.

History of Cochrane

The value of this approach was increasingly appreciated, with the Cochrane Collaboration being formed in 1993, with 77 people from nine countries, growing over 25 years to 13,000 members and 50,000 supporters from more than 130 countries. Cochrane reviews are available online and are revised periodically to provide up-to-date summary information about a wide range of areas, principally health interventions, but also diagnostic testing, prognosis and other topics.

21.2 Steps in the literature review

The following steps are adapted from Hemingway & Brereton (2009)’s simplified account of how to conduct a systematic review:

21.2.1 Define an appropriate question

This is often harder than anticipated. Cochrane guidelines point to the PICO mnemomic, which notes the need to specify the Population, Intervention, Comparison(s) and Outcome:

- for Population, you need to consider which kinds of clients will be included in the review - e.g. age ranges, social and geographical background, diagnosis, and so on.

- For Intervention, one has to decide whether to adopt a broad or narrow scope. For instance, given the small amount of relevant literature, a Cochrane review by Law et al. (2003) entitled “Speech and language therapy interventions for children with primary speech and/or language disorders” took a very broad approach, including a wide range of interventions, subdivided only according to whether their focus was on speech, expressive language or receptive language. This meant, however, that quite disparate interventions with different theoretical bases were grouped together. We anticipate that for readers of this book, the interest will be in a specific intervention, so a narrow scope is appropriate.

- Comparison refers to the need to specify what is the alternative to the intervention. You could specify here that only RCTs will be included in the review.

- For Outcome, the researcher specifies what measures of outcome will be included. These can include adverse events as well as measures of positive benefits.

Thus rather than asking “Is parent training effective in improving children’s communication?”, it is preferable to specify a question such as “Do RCTs of parent training (as implemented in one or more named specific methods) lead to higher scores than a control group on a measure of communicative responsiveness in children aged between 12 and 24 months?”

Two important recommendations by Cochrane are first, that user engagement is important for specifying a question; this helps avoid research that will not be of practical value because its focus is too academic or narrow. Second, in considering outcomes, it is recommended that consideration be given to possible negative consequences as well as potential benefits of the intervention.

21.2.2 Specify criteria for a literature search

The goal is to identify all relevant evidence on the research question of interest, and the usual approach is to start by specifying keywords that will be entered into a literature search. Again, this might seem easy, but in practice it requires expertise, both in identifying relevant keywords, and in selecting suitable databases for the search. It is worth taking advice from an academic librarian on this point.

In addition, we know that publication bias occurs, and so efforts need to be made to find relevant unpublished studies, that may be written up in preprints or theses. The search often proceeds through different stages, starting with a formal literature search, but then adding additional studies found by perusing the reference list of relevant papers. At this point, it is better to be overinclusive than underinclusive.

21.2.3 Select eligible studies following protocol’s inclusion criteria

The next step is a screening process, which typically whittles down the list of potential studies for inclusion by a substantial amount. Abstracts for the studies found in the previous step are scrutinsed to see which should be retained. For example, if the protocol specified that studies had to be randomized controlled trials, then any study that did not include randomization or that lacked a control group would be excluded at this stage. This is a key step where it is good to have more than one person doing the screening, to reduce subjective bias and to minimize the workload.

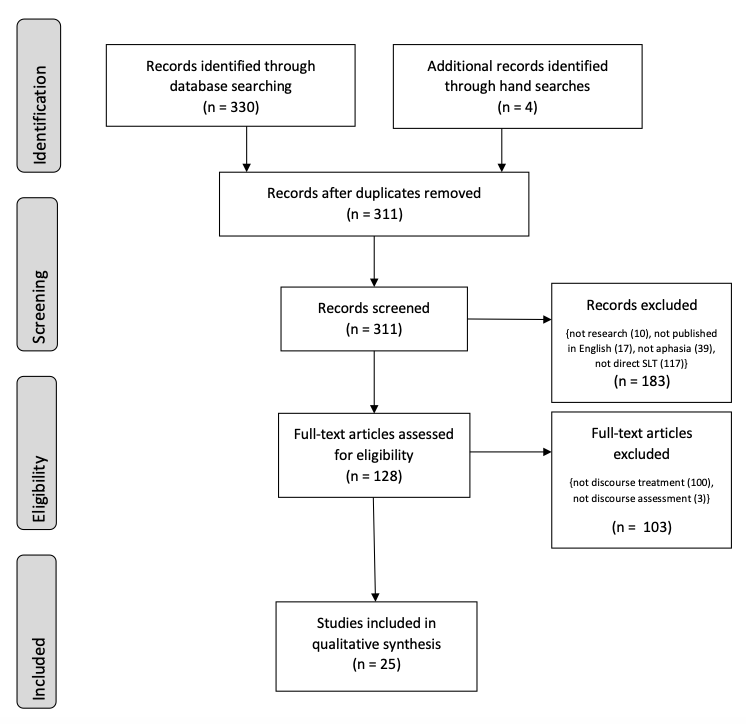

In a freestanding systematic review, it is customary to provide a flow chart documenting the numbers of papers considered at each stage. A template for a standard flow chart can be downloaded from the PRISMA website.

Figure 21.1: PRISMA flowchart from Dipper et al. (2020)

Figure 21.1 shows a completed flowchart for a study of intervention to improve discourse in patients with aphasia; the initial search found 334 records, but on further screening, only 25 of these met eligibility criteria. The need to screen considerably more articles than the final included set is one factor that makes systematic reviews so time-consuming. It may be possible to enlist students to help with screening. For those who are familiar with the computer language R, the metagear package in R is very useful for speeding up screening, by automating part of the process of extracting and evaluating abstracts for suitability.

21.2.4 Assess the quality of each study included

At this stage the methodology of each study is scrutinized to see whether it meets predefined quality criteria. Some studies may be excluded at this stage; for others, a rating is made of quality so that higher weighting can be given to those with high quality - i.e., those that have been designed to minimize the kinds of bias we have focused on in this book.

A wide range of checklists has been developed to help with quality appraisal, some of which are lengthy and complex. The questionnaires available from the Centre for Evidence-Based Management (CEBMa) are reasonably user-friendly and include versions for different study types.

In our experience, evaluating quality of prior research is the most difficult and time-consuming aspect of a literature review, but working through a study to complete a CEBMa questionnaire can be a real eye-opener, because it often reveals problems with studies that are not at all evident when one just reads the Abstract. Researchers may be at pains to hide the weaknesses in their study, and all-too-often inconvenient information is just omitted. There may be substantial discrepancies between what is stated in the Abstract and the Results section - classic spin (see Chapter 19). Evaluating quality can be a very valuable exercise for the researcher, not just for deciding how much faith to place in study results, but also for identifying shortcomings of research that can, hopefully, be avoided in one’s own study.

One can see that this stage is crucial and, even with well-defined quality criteria, there could be scope for subjective bias, so ideally two raters should evaluate each study independently so the amount of agreement be recorded. Disagreements can usually be resolved by discussion. Even so, a sole researcher can produce a useful review by following these guidelines, provided that the process is documented transparently, with reasons for specific decisions being recorded.

21.2.5 Organize, summarize, and unbiasedly present the findings from all included studies

For a Cochrane systematic review, the analysis will have been prespecified and pre-registered. In medical trials, a commmon goal is to extract similar information from each trial on effect sizes and combine this in a meta-analysis, which provides a statistical approach to integrating findings across different studies. A full account of meta-analysis is beyond the scope of this book, but for further information, see Borenstein et al. (2009). Worked examples of meta-analysis in R are available online.

For the typical literature review in the field of speech and language therapy, the literature is likely to be too small and/or heterogeneous for meaningful meta-analysis, and narrative review then makes more sense, i.e. the author describes the results of the different studies, noting factors that might be looked at in future as potential influences of outcomes. Findings from the quality evaluation should be commented on here to help readers understand why some studies are given more weight than others when pulling the literature together.

21.3 Systematic review or literature review?

As we have seen, there are critical differences between a formal systematic review that follows Cochrane methods and a literature review. A well-executed systematic review is considered to be one of the most reliable sources of evidence beyond the RCT and is specific to a particular research question. It will often incorporate a meta-analytic procedure, and the end result will be a stand-alone publication.

Traditionally, the literature review that is included in the introduction to a research article is less structured and focuses on qualitative appraisal of either a general topic or specific question in the literature. Systematic reviews have tended to be seen as quite separate from more traditional literature reviews, because of the rigorous set of procedures that must be followed, but we have argued here that it is possible to use insights from systematic review methods, even if we do not intend to follow all the criteria that are required for that approach, as this will improve the rigour of the review and help avoid the kind of citation bias that pervades most fields.

When writing up a literature review, the key thing is to be aware of a natural tendency to do two things, which map rather well onto our earlier discussions of random and systematic bias. Random bias, or noise, gets into a literature review when researchers are simply unscholarly and sloppy. We are all very busy and it is tempting to just read the Abstract of a paper rather than wade through the whole article. This is dangerous, because Abstracts often are selective in presenting the “best face” of the results, rather than the whole picture. Learning to do a good quality evaluation of a paper is an important skill for any researcher.

The second natural tendency is to show systematic bias, as discussed in Chapter 19. We are naturally inclined to look only for studies that support our pre-existing views. If we have a mixture of studies, some supportive and others not, we are likely to look far more critically at those whose results we would like to disregard. By following the steps of literature review listed above, we are helped to look at the evidence in an objective way.

21.4 Class exercise

If possible, it is useful to do this exercise in groups of 2-4. The group should identify a paper that evaluates an intervention, and then consult this website to find a Questionnaire that matches the methodology.

Each group member should first spend 20-30 minutes attempting to complete the questionnaire independently for the paper. Then come together and compare notes and discuss:

- Were there points of disagreement? If so, what caused these?

- How easy was it to evaluate the paper?

- Was crucial information missing? (It often is!)

- Did the Abstract give an accurate indication of the Results of the paper?