Chapter 12 The randomized controlled trial as a method for controlling biases

The randomized controlled trial (RCT) is regarded by many as the gold standard method for evaluating interventions. In the next chapter we will discuss some of the limitations of this approach that can make it less than ideal for evaluating certain kinds of non-medical interventions. But in this chapter we’ll look at the ingredients of a RCT that make it such a well-regarded method, and introduce the basic methods that can be used to analyse the results.

A RCT is effective simply because it is designed to counteract all of the systematic biases that were covered in previous Chapters.

| Biases | Remedies |

|---|---|

| Spontaneous improvement | Control group |

| Practice effects | Control group |

| Regression to the mean | Control group |

| Noisy data (1) | Strict selection criteria for participants |

| Noisy data (2) | Outcome measures with low measurement error |

| Selection bias | Random assignment to intervention |

| Placebo effects | Participant unaware of assignment |

| Experimenter bias (1) | Experimenter unaware of assignment |

| Experimenter bias (2) | Strictly specified protocol |

| Biased drop-outs | Intention-to-treat analysis |

| Low power | A priori power analysis |

| False positives due to p-hacking | Registration of trial protocol |

We cannot prevent changes in outcomes over time that arise for reasons other than intervention (Chapter 4), but if we include a control group we can estimate and correct for their influence. Noisy data in general arises either because of heterogenous participants, or because of unreliable measures: in a good RCT there will be strict selection criteria for participants, and careful choice of outcome measures to be psychometrically sound (see Chapter 3). Randomization of participants to intervention and control groups avoids bias caused either by participants’ self-selection of intervention group, or experimenters’ determining who gets what treatment. In addition, as noted in Chapter 4 and Chapter 8, where feasible, both participants and experimenters are kept unaware of who is in which treatment group, giving a double-blind RCT.

In Chapter 11, we noted that the rate of false positive results in a study can be increased by p-hacking, where many outcome measures are included but only the “significant” ones are reported. This problem has been recognized in the context of clinical trials for many years, which is why clinical trial protocols are usually registered specifying a primary outcome measure of interest: indeed, as is discussed further in Chapter 20, many journals will not accept a trial for publication unless it has been registered on a site such as https://clinicaltrials.gov/. Note, however, that, as discussed in Chapter 11, multiple outcomes may increase the statistical power of a study, and are not a problem if the statistical analysis handles the multiplicity correctly. Secondary outcome measures can also be specified, but reporting of analyses relating to these outcomes should make it clear that they are much more exploratory. In principle, this should limit the amount of data dredging for an effect that is loosely related to the hypothesis of interest (typically, “is the intervention effective?”).

RCTs have become such a bedrock of medical research that standards for reporting them have been developed. In Chapter 9 we saw the CONSORT flowchart, which is a useful way of documenting the flow of participants through a trial. CONSORT stands for Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials, which are endorsed by many medical journals. Indeed, if you plan to publish an intervention study in one of those journals, you are likely to be required to show you have followed the guidelines. The relevant information is available on the ‘Enhancing the QUAlity and Transparency Of health Research’ EQUATOR network website. The EQUATOR network site covers not only RCTs but also the full spectrum guidelines of many types of clinical research designs.

For someone starting out planning a trial, it is worth reading the CONSORT Explanation and Elaboration document (Moher et al., 2010), which gives the rationale behind different aspects of the CONSORT guidelines. This may seem rather daunting to beginners, as it mentions more complex trial designs as well as a standard RCT comparing intervention and control groups, and it assumes a degree of statistical expertise (see below). It is nevertheless worth studying, as adherence to CONSORT guidelines is seen as a marker of study quality, and it is much easier to conform to their recommendations if a study is planned with the guidelines in mind, rather than if the guidelines are only consulted after the study is done.

12.1 Statistical analysis of a RCT

Statisticians often complain that researchers will come along with a collection of data and ask for advice as to how to analyse it. Sir Ronald Fisher (one of the most famous statisticians of all time) commented:

“To consult the statistician after an experiment is finished is often merely to ask him to conduct a post mortem examination. He can perhaps say what the experiment died of.”

-Sir Ronald Fisher, Presidential Address to the First Indian Statistical Congress, 1938.

His point was that very often the statistician would have advised doing something different in the first place, had they been consulted at the outset. Once the data are collected, it may be too late to rescue the study from a fatal flaw.

Many of those who train as allied health professionals get rather limited statistical training. We suspect it is not common for them to have ready access to expert advice from a statistician. We have, therefore, a dilemma: many of those who have to administer interventions have not been given the statistical training that is needed to evaluate their effectiveness.

We do not propose to try to turn readers of this book into expert statisticians, but we hope to instill a basic understanding of some key principles that will make it easier to read and interpret the research literature, and to have fruitful discussions with a statistician if you are planning a study.

The answer to the question “How should I analyse my data?” depends crucially on what hypothesis is being tested. In the case of an intervention trial, the hypothesis will usually be “did intervention X make a difference to outcome Y in people with condition Z?” There is, in this case, a clear null hypothesis – that the intervention was ineffective, and the outcome of the intervention group would have been just the same if it had not been done. The null hypothesis significance testing approach answers just that question: it tells you how likely your data are if the the null hypothesis was true. To do that, you compare the distribution of outcome scores in the intervention group and the control group, as explained in Chapter 10. And as emphasized earlier, we don’t just look at the difference in means between two groups, we consider whether that difference is greater than you’d expect given the variation within the two groups. (This is what the term “analysis of variance” refers to).

12.2 Steps to take before data analysis

- General sanity check on dataset - are values within expected range?

- Check assumptions

- Plot data to get sense of likely range of results

12.2.1 Sample dataset with illustrative analysis

To illustrate data analysis, we will use a real dataset that can be retrieved from the ESRC data archive (Burgoyne et al., 2016). We will focus only on a small subset of the data, which comes from an intervention study in which teaching assistants administered an individual reading and language intervention to children with Down syndrome. A wait-list RCT design was used (see Chapter 17), but we will focus here on just the first two phases, in which half the children were randomly assigned to intervention, and the remainder formed a control group. Several language and reading measures were included in the study, giving a total of 11 outcomes. Here we will illustrate the analysis with just one of the outcomes - letter-sound coding - which was administered at baseline (t1) and immediately after the intervention (t2). Results from the full study have been reported by Burgoyne et al. (2012) and are discussed in the demonstration of MEff by Bishop (2023).

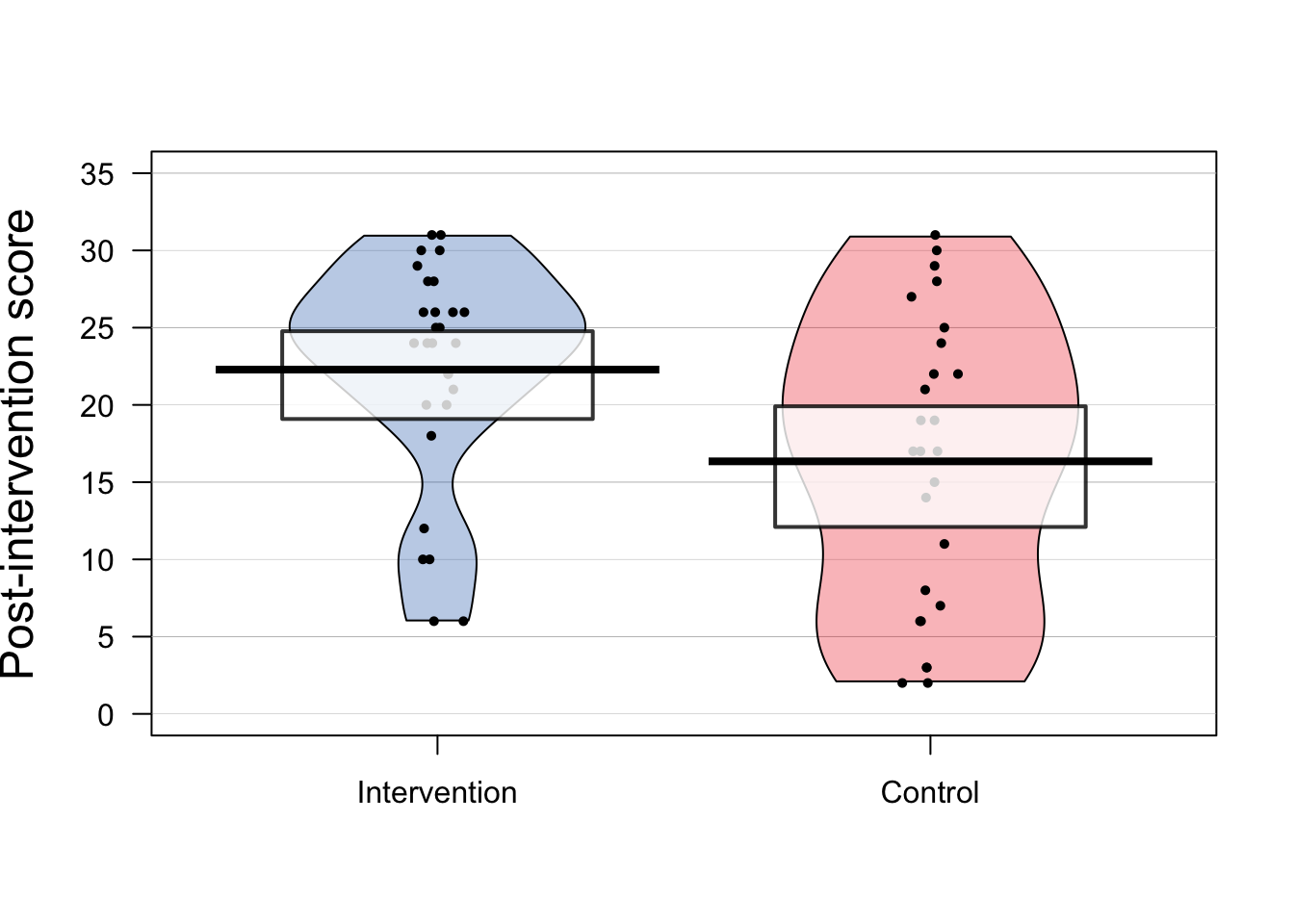

Figure 12.1: Data from RCT on language/reading intervention for Down syndrome by Burgoyne et al. (2012)

Figure 12.1 shows results on letter-sound coding after one group had received the intervention. This test had also been administered at baseline, but we will focus first just on the outcome results.

Raw data should always be inspected prior to any data analysis, in order to just check that the distribution of scores looks sensible. One hears of horror stories where, for instance, an error code of 999 got included in an analysis, distorting all the statistics. Or where an outcome score was entered as 10 rather than 100. Visualising the data is useful when checking whether the results are in the right numerical range for the particular outcome measure. The pirate plot is a useful way of showing means and distributions as well as individual data points.

A related step is to check whether the distribution of the data meets the assumptions of the proposed statistical analysis. Many common statistical procedures assume that data are normally distributed on an interval scale (see Chapter 3). Statistical approaches to checking of assumptions are beyond the scope of this book, but there are good sources of information on the web, such as this website for linear regression. But just eyeballing the data is useful, and can detect obvious cases of non-normality, cases of ceiling or floor effects, or “clumpy” data, where only certain values are possible. Data with these features may need special treatment and it is worth consulting a statistician if they apply to your data. For the data in Figure 12.1, although neither distribution has an classically normal distribution, we do not see major problems with ceiling or floor effects, and there is a reasonable spread of scores in both groups.

| Group | N | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention | 28 | 22.286 | 7.282 |

| Control | 26 | 16.346 | 9.423 |

The next step is just to compute some basic statistics to get a feel for the effect size. Table 12.2 shows the mean and standard deviation on the outcome measure for each group. The mean is the average of the individual datapoints shown in Figure 12.1, obtained by just summing all scores and dividing by the number of cases. The standard deviation gives an indication of the spread of scores around the mean. As discussed in Chapter 10, the SD is a key statistic for measuring an intervention effect. In these results, one mean is higher than the other, but there is overlap between the groups. Statistical analysis gives us a way of quantifying how much confidence we can place in the group difference: in particular, how likely is it that there is no real impact of intervention and the observed results just reflect the play of chance. In this case we can see that the difference between means is around 6 points and the average SD is around 8, so the effect size (Cohen’s d) is about .75 - a large effect size for a language intervention.

12.2.2 Simple t-test on outcome data

The simplest way of measuring the intervention effect is to just compare outcome (posttest) measures on a t-test. We can use a one-tailed test with confidence, given that we anticipate outcomes will be better after intervention. One-tailed tests are often treated with suspicion, because they can be used by researchers engaged in p-hacking (see Chapter 11), but where we predict a directional effect, they are entirely appropriate and give greater power than a two-tailed test: see this blogpost by Daniël Lakens.

When reporting the result of a t-test, researchers should always report all the statistics: the value of t, the degrees of freedom, the means and SDs, and the confidence interval around the mean difference, as well as the p-value. This not only helps readers understand the magnitude and reliability of the effect of interest: it also allows for the study to readily be incorporated in a meta-analysis. Results from a t-test for the data in Table 12.2 are shown in Table 12.3. Note that with a one-tailed test, the confidence interval on one side will extend to infinity: this is because a one-tailed test assumes that the true result is greater than a specified mean value, and disregards results that go in the opposite direction.

| t | df | p | mean diff. | lowerCI | upperCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.602 | 52 | 0.006 | 5.94 | 2.117 | Inf |

12.2.3 T-test on difference scores

The t-test on outcomes is easy to do, but it misses an opportunity to control for one unwanted source of variation, namely individual differences in the initial level of the language measure. For this reason, researchers often prefer to take difference scores: the difference between outcome and baseline measures, and apply a t-test to these. While this had some advantages over reliance on raw outcome measures, it also has disadvantages, because the amount of change that is possible from baseline to outcome is not the same for everyone. A child with a very low score at baseline has more “room for improvement” than one who has an average score. For this reason, analysis of difference scores is not generally recommended.

12.2.4 Analysis of covariance on outcome scores

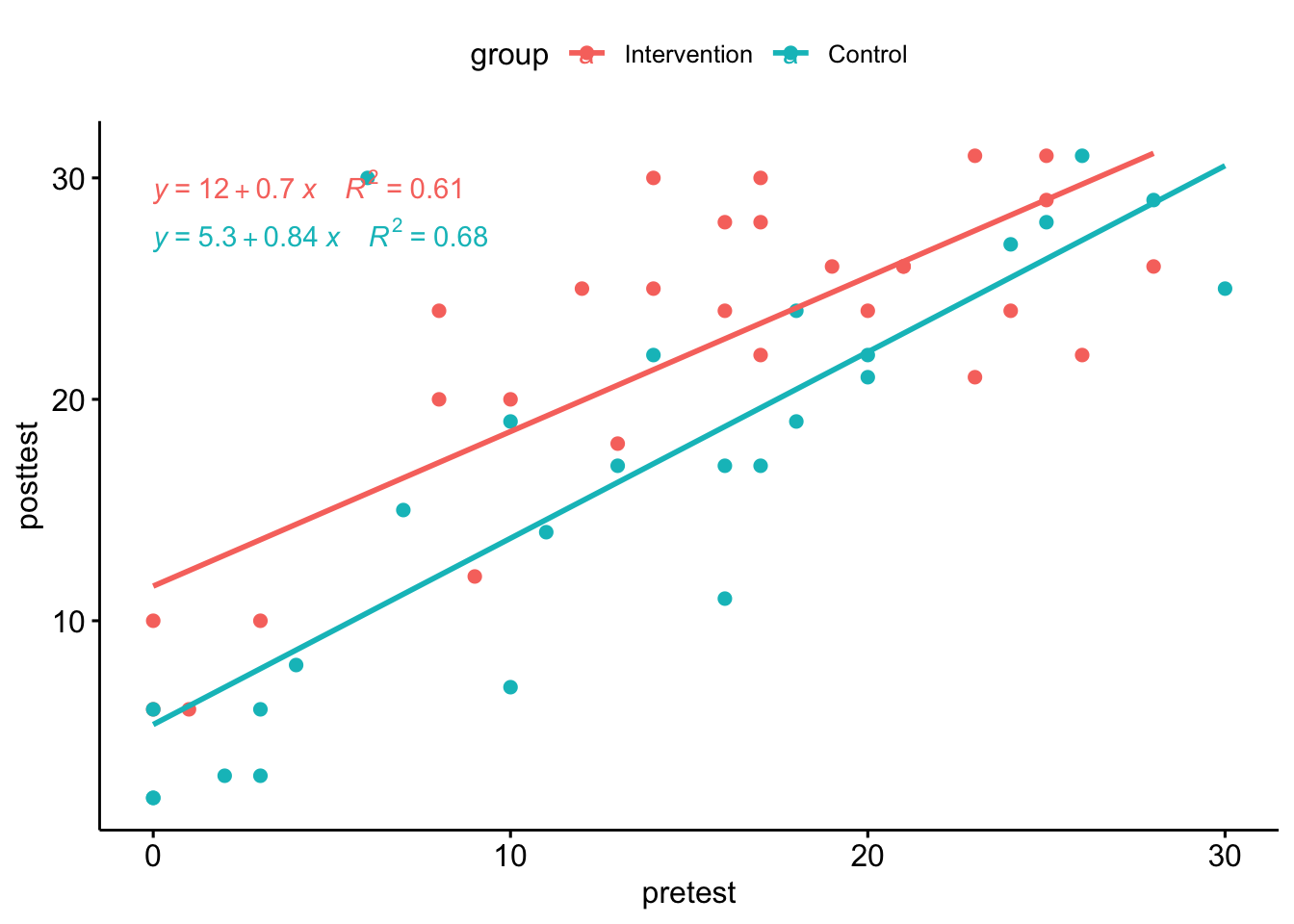

Rather than taking difference scores, it is preferable to analyse differences in outcome measures after making a statistical adjustment that takes into account the initial baseline scores, using a method known as analysis of covariance or ANCOVA. In practice, this method usually gives results that are very similar to those you would obtain from an analysis of difference scores, but the precision, and hence the statistical power is greater. However, the data do need to meet certain assumptions of the method. This website walks through the steps for performing an ANCOVA in R, starting with a plot of to check that there is a linear relationship between pretest vs posttest scores in both groups - i.e. the points cluster around a straight line, as shown in Figure 12.2.

Figure 12.2: Pretest vs posttest scores in the Down syndrome data

Inspection of the plot confirms that the relationship between pretest and posttest looks reasonably linear in both groups. Note that it also shows that there are rather more children with very low scores at pretest in the control group. This is just a chance finding - the kind of thing that can easily happen when you have relatively small numbers of children randomly assigned to groups.

| Effect | DFn | DFd | F | p | ges |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| group | 1 | 52 | 6.773 | 0.012 | 0.115 |

| Effect | DFn | DFd | F | p | ges |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pretest | 1 | 51 | 94.313 | 0.000 | 0.649 |

| group | 1 | 51 | 9.301 | 0.004 | 0.154 |

Table 12.4 shows the same data analysed by first of all by using ANOVA to compare only the post-test scores (upper chart) and then using ANCOVA to adjust scores for the baseline (pretest) values. The effect size is shown as ges, which stands for “generalized eta squared”. You can see there is a large ges value, and correspondingly low p-value for the pretest term, reflecting the strong correlation between pretest and posttest shown in Figure 12.2. In effect, with ANCOVA, we adjust scores to remove the effect of the pretest on the posttest scores; in this case, we can then see a slightly stronger effect of the intervention: the effect size for the group term is higher and the p-value is lower than with the previous ANOVA.

For readers who are not accustomed to interpreting statistical output, the main take-away message here is that you get a better estimate of the intervention effect if the analysis uses a statistical adjustment that takes into account the pre-test scores.

T-tests, analysis of variance, and linear regression

See this blogpost for more details.

12.2.5 Linear mixed models (LMM) approach

Increasingly, reports of RCTs are using more sophisticated and flexible methods of analysis that can, for instance, cope with datasets that have missing data, or where distributions of scores are non-normal.

An advantage of the LMM approach is that it can be extended in many ways to give appropriate estimates of intervention effects in more complex trial designs - some of which are covered in Chapter 15 to Chapter 18). Disadvantages of this approach are that it is easy to make mistakes in specifying the model for analysis if you lack statistical expertise, and the output is harder for non-specialists to understand. If you have a simple design, such as that illustrated in this chapter, with normally distributed data, a basic analysis of covariance is perfectly adequate (O’Connell et al., 2017).

Table 12.5 summarises the pros and cons of different analytic approaches.

| Method | Features | Ease of understanding | Flexibility |

|---|---|---|---|

| t-test | Good power with 1-tailed test. Suboptimal control for baseline. Assumes normality. | High | Low |

| ANOVA | With two-groups, equivalent to t-test, but two-tailed only. Can extend to more than two groups. | … | … |

| Linear regression/ ANCOVA | Similar to ANOVA, but can adjust outcomes for covariates, including baseline. | … | … |

| LMM | Flexible in cases with missing data, non-normal distributions. | Low | High |

12.3 Class exercise

Find an intervention study of interest and check whether the protocol was deposited in a repository before the study began. If so, check the analysis against the preregistration, cf. Goldacre et al. (2019). Note which analysis method was used to estimate the intervention effect.

Did the researchers provide enough information to give an idea of the effect size, or merely report p-values? Did the analysis method take into account baseline scores in an appropriate way?In Chapter 13 we consider drawbacks of the RCT design. Before you read that chapter, see if you can anticipate the issues that we consider in our evaluation.