Chapter 4 Improvement due to nonspecific effects of intervention

4.1 Placebo effects

Most of us are familiar with the placebo effect in medicine: the finding that patients can show improvement in their condition even if given an inert sugar pill. There is much debate about the nature of placebo effects – whether they are mostly due to the systematic changes discussed in Chapter 2, or something else. They are thought to operate in cognitive and behavioural interventions as well: communication may improve in a person with aphasia because they have the attention of a sympathetic professional, rather than because of anything that professional does. And children may grow in confidence because they are made to feel valued and special by the therapist.

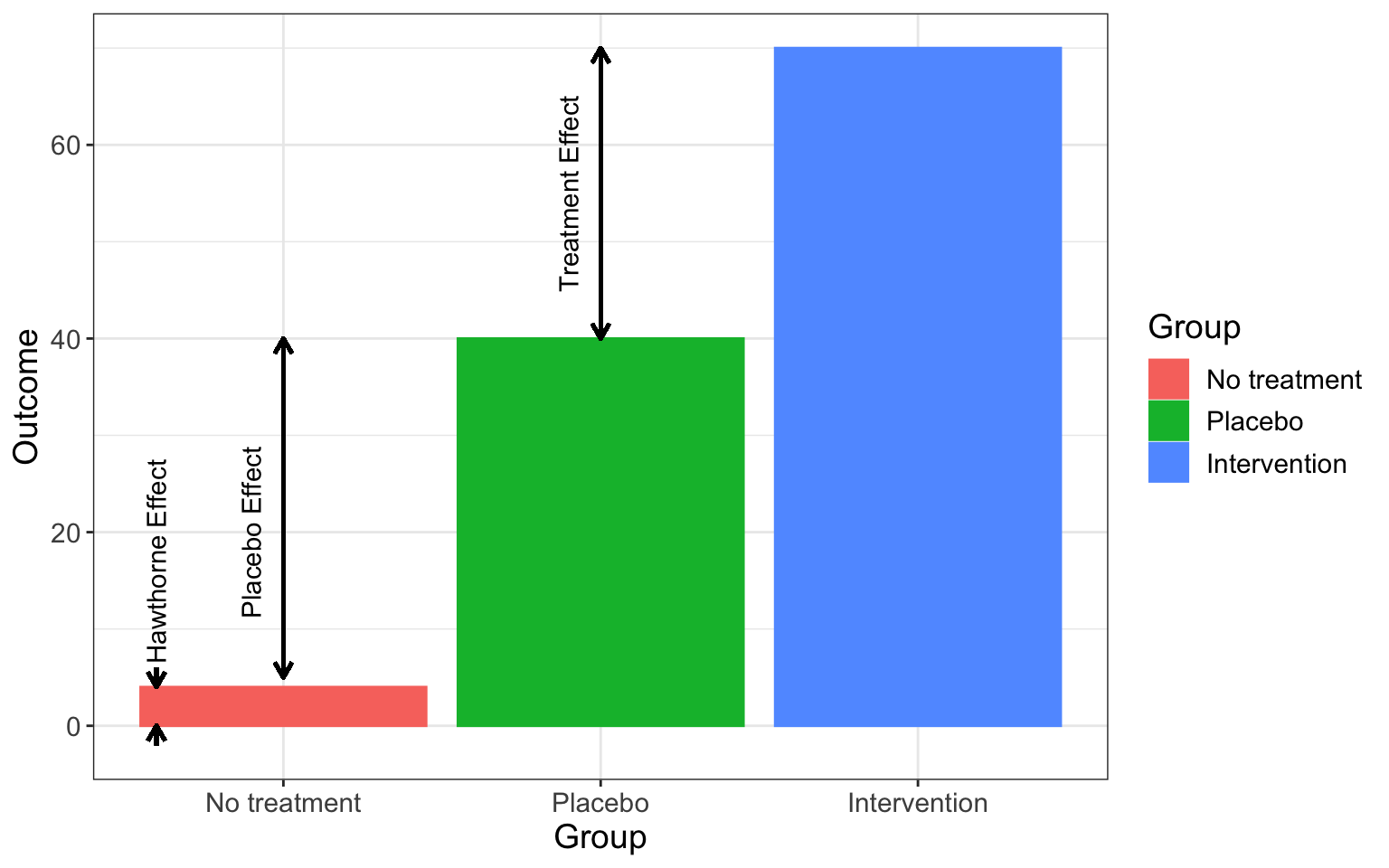

Figure 4.1: Placebo effect in a three-arm parallel group trial

The Hawthorne Effect?

The placebo effect in behavioural interventions is often discussed in conjunction with the Hawthorne effect, which refers to a tendency for people to change their behaviour as a result of simply being the focus of experimental attention. The name comes from the Hawthorne Works in Cicero, Illinois, where a study was done to see the effects of lighting changes and work structure changes such as working hours and break times on worker productivity. These changes appeared to improve productivity, but subsequent work suggested this was a very general effect that could be produced by almost any change to working practices. However, there is a twist in the tail. The original factory studies on the Hawthorne effect have been described as “among the most influential experiments in social science”. Yet, like so many classic phenomena in social science, the work attracted critical scrutiny years after it was conducted, and the effect turns out to be far less compelling than was previously thought. The paper “Was there really a Hawthorne effect at the Hawthorne plant?” (Levitt & List, 2011) describes how the authors dug out and reanalysed the original data from the study, concluding that “an honest appraisal of this experiment reveals that the experimental design was not strong, the manner in which the studies were carried out was lacking, and the results were mixed at best…”.

Most therapists would regard such impacts on their clients as entirely valid outcomes of the intervention – boosting functional communication skills and confidence are key goals of any intervention package. But it is important, nevertheless, to know whether the particular intervention adopted has a specific effect. Many individualized speech/language interventions with both adults and children involve complicated processes of assessment and goal-setting with the aim of achieving specific improvements. If these are actually ineffective, and the same could be achieved by simply being warm, supportive and encouraging, then we should not be spending time on them.

Generalized beneficial effects of being singled out for intervention can also operate via teachers. In a famous experiment, Rosenthal and Jackson (1963) provided teachers with arbitrary information about which children in their class were likely to be “academic bloomers”. They subsequently showed that the children so designated obtained higher scores at a later point, even though they had started out no different from other children. In fact, despite its fame, the Rosenthal and Jackson result is based on data that, by modern standards, are far from compelling, and it is not clear just how big an effect can be produced by raising teacher expectations. Nevertheless, the study provides strong motivation for researchers to be cautious about how they introduce interventions, especially in school settings. If one class is singled out to receive a special new intervention, it is likely that the teachers will be more engaged and enthusiastic than those who remain in other classes where it is “business as usual”. We may then be misled into thinking that the intervention is effective, when in fact it is the boost to teacher engagement and motivation that has an impact.

Study participants themselves may also be influenced by general positive impact of being in an intervention group – and indeed it has been argued that there can be an opposite effect – a nocebo effect – for those who know that they are in a control group, while others are receiving intervention. This is one reason why some studies are conducted as “double blind” trials – meaning that neither the participant nor the experimenter knows who is in which intervention group. But this is much easier to achieve when the intervention is a pill (when placebo pills can be designed to look the same as active pills) than when it involves communicative interaction between therapist and client. Consequently, in most studies in this field, those receiving intervention will be responding not just to the specific ingredients of the intervention, but also to any general beneficial effects of the therapeutic situation.

4.2 Identifying specific intervention effects by measures of mechanism

There are two approaches that can be taken to disentangle nonspecific effects from specific impact of a particular intervention. First, we can include an active control group who get an equivalent amount of therapeutic attention, but directed towards different goals. We will discuss this further in Chapter 6, which focuses on different approaches to control groups. The second is to include specially selected measures designed to clarify and highlight the active ingredients of the intervention. We will refer to these as ‘mechanism’ measures, to distinguish them from outcome measures.

Let’s take the example of parent-based intervention with a late-talking toddler. In extended milieu therapy, the therapist encourages the parent to change their style of communication in naturalistic contexts in specific ways. The ultimate goal of the intervention is to enhance the child’s language, but the mechanism is via changes in the parent’s communicative style. If we were to find that the child’s language improved relative to an untreated control group but there was no change in parental communication (our mechanism measure), then this would suggest we were seeing some general impact of the therapeutic contact, rather than the intended effect of the intervention (See Figure 4.1).

To take another example, the theory behind the computerized Fast ForWord® (FFW) intervention maintains that children’s language disorders are due to problems in auditory processing that lead them to be poor at distinguishing parts of the speech signal that are brief, non-salient or rapidly changing. The intervention involves exercises designed to improve auditory discrimination of certain types of sounds, with the expectation that improved discrimination will lead to improved general language function. If, however, we were to see improved language without the corresponding change in auditory discrimination (a mechanism measure), this would suggest that the active ingredient in the treatment is not the one proposed by the theory.

Note that in both these cases it is possible that we might see changes in our mechanism measure, without corresponding improvement in language. Thus we could see the desired changes in parental communicative style with extended milieu therapy, or improved auditory discrimination with FFW, but little change in the primary outcome measure. This would support the theoretical explanation of the intervention, while nevertheless indicating it was not effective. The approach might then either be abandoned or modified – it could be that children would need longer exposure, for instance, to produce a clear effect.

The most compelling result, however, is when there is a clear difference between an intervention and a treated control group in both the mechanism measure and the outcome measure, with the two being positively related within the treated group. This would look like good evidence for a specific intervention effect that was not just due to placebo.

It is not always easy to identify a “mechanism” measure – this will depend on the nature of the intervention and how specific its goals are. For some highly specific therapies – e.g. a phonological therapy aimed at changing a specific phonological process, or a grammatical intervention that trains production of particular morphological forms, the “mechanism” measure might be similar to the kind of “near transfer” outcome measure that was discussed in Chapter 3 – i.e., a measure of change in performance on the particular skill that is targeted. As noted above, we might want to use a broader assessment for our main outcome measure, to indicate how far there is generalization beyond the specific skills that have been targeted.

4.3 Class exercise

In their analysis of the original data on the Hawthorne effect, Levitt & List (2011) found that output rose sharply on Mondays, regardless of whether artificial light was altered. Should we be concerned about possible effects of the day of the week or the time of day on intervention studies? For instance:

Would it matter if all participants were given a pre-test on Monday and a post-test on Friday?

Or if those in the control group were tested in the afternoon, but those in the intervention group were tested in the morning?