Chapter 5 Money, Banking and the Financial Sector

At the end of this chapter you should understand

How the financial system is represented in the economy

The central bank lending rate and the policy rate

Credit rationing and information asymmetries

Bank liquidity, solvency and the balance sheet

Bank

This chapter is about the role of money and banking in the macro economy. This subject has been ignored in some macroeconomic models. Models such as the Real Business Cycle assume that the financial system operates smoothly without any frictions. If the system is working well, economic agents can carry out their planned expenditure using money and credit. However, the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) made clear the disruption that may be felt when the financial system is not working well.

There are two new features introduced to the model when we look more closely at the financial system:

There is a distinction between the policy rate and the lending rate;

Banks intermediate between depositors and borrowers and impose borrowing constraints on some parties (credit rationing);

5.1 Banking mark-up

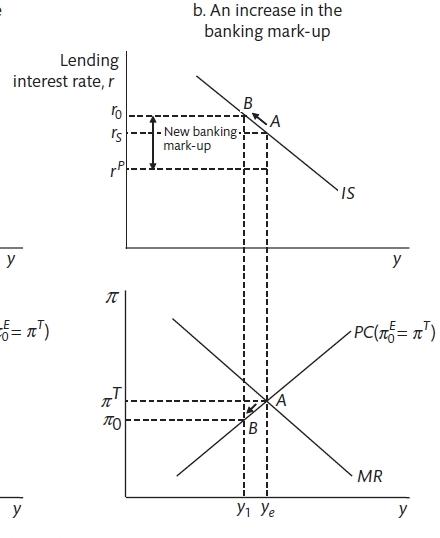

Up to now the central bank has been able to set the interest rate to obtain the level of economic activity that is required. However, it is necessary to distinguish between the bank rate and the lending rate that is set by financial institutions. It is the lending rate that is important for economic agent financial decisions. The lending rate is the mark-up on the policy rate that is determined by the banks' optimising decisions. For the IS curve, we now have the lending rate on the y-axis and denote the Policy rate as that set by the central bank. The difference between the two is banking mark-up. This allows an analysis of shocks to the banking system that can widen the spread.

The Banking Mark-up (Carlin and Soskice 2015)

If there is a shock to the banking system unanticipated by the central bank that results in an increase in the margin that banks charge above the policy rate (maybe because they become more concerned about bad loans), this will cause an unanticipated shift along the IS curve and will push the economy below the stabilising level of output. In these cases, the central bank must cut interest rates to reduce the lending rate and bring output back to the stabilising level.

5.2 Money and the macroeconomic

Money has three functions:

- Means of transaction. It is used to buy things. There is no need to barter. The more transactions the more money that is required.

- Unit of account. It allows comparison. If the value of money changes rapidly, it is difficult to use for comparison.

- Store of value. It is used for savings. If it loses value it is not useful for saving.

Households select the amount of cash that they want to hold. This will be determined by their desire to purchase goods, repay debts and buy assets. It will also be determined by technology (cash alternatives). Banks determine the amount of reserves that they hold by estimating how much they need for customer requests and for settling balances with other banks. Generally, other assets will yield more than reserves. The liquidity ratio is the ratio of reserves to bank deposits. Therefore, central bank cash is determined by the liquidity ratio, the cash demanded by households and the size of bank deposits. Subject to the liquidity constraint (liquidity rate), commercial banks will create money by making loans when it is profitable to do so. This will depend on the demand for loans, which is set by the IS curve, and the funding costs set by the central bank. Cash is less than 3% of a modern economy. It is assumed that bank deposits do not pay interest and that households can hold either cash, deposits or government bonds. In reality we should also add corporate equity and corporate bonds as potential assets that households could buy.

The commercial bank money is determined by the size of current accounts. Households and firms determine the amount of cash that they will hold. This will be deponent on their income and the level of interest rates. As income increases, households will want to conduct more transactions and will need more money to do that; as interest rates rise, the return on bonds becomes higher and makes bank deposits less attractive.

\[\frac{M^D}{P} = f(y, i, \Phi)\]

Where \(y\) is income, \(i\) is the nominal interest rate and \(/phi\) is the structural changes that take place in the financial sector (such as ATM machines). Given the Fisher equation \((i = r + \pi^E)\), if inflation goes up, this adds to the opportunity cost of holding money and demand will fall. These private sector decisions in combination with the policy of the central bank will set the amount of money. \(\Phi\) can also be used to capture things like a change in confidence. In the period after 2008 when there was a loss of confidence in the financial system, the demand for pure cash increased. Fluctuations in the demand for cash as a safe asset mean that the relationship betweeen money and spending is not very stable.

5.3 The financial system

The policy rate is the rate that the central bank lends money to the banking system. If there is payment on reserves, this provides the mechanism that keeps other short-term interest rates close to the policy rate. The reserve rate acts as a floor. It is the lending rate that determines demand in the economy (via the IS rate).

Commercial banks will face a demand for loans and a cost of funds. They will borrow from the money market if they do not have sufficient deposits. It is assumed that banks are profit-maximisers. Profits depend on: expected return on loans, cost of funds in the money market and the opportunity cost of bank capital. The expected return will be affected by credit risk (even on secured loans). Bank risk tolerance will vary and the ability of the bank to bear risk will depend on how much capital it has. The spread between the policy rate and the lending rate is determined by risk, risk tolerance and capital. The interest rate margin or banking mark-up equation is

\[r = (1 + \mu^B)r^P\]

\(\mu^B\) is the banking mark-up that depends positively on risk and negatively on risk tolerance and capital.

The policy rate and money market rates are more or less equal in normal conditions. The level of competition in the banking industry will also affect the mark-up of lending rates over policy rates in the medium term. The relatively low level of competition in the UK banking market is believed to make borrowing relatively expensive for UK borrowers with minimal alternatives forms of finance. (Kleimeier and Sander 2017) find that level of comeptition is the most important, but not the only influence on the extent that central bank interest rate changes are passed through to other interest rates in the economy. There are also debates about the relatinship between the level of competition and the stability of the financial system with some suggestions that more competition encourages more risky behaviour.

5.4 Credit constraints

Credit rationing is a key feature of the banking system that stems from asymmetric information. This means that households face credit constraints. These credit constrains affect the slope of the IS curve and the power of the multiplier. It is hard for lenders to distinguish between bad luck and moral hazard. The more that borrowers use their own wealth to fund a project, the more confident the bank can be. The lender also has less precise information about future earnings. If a bank charges an average rate, there is a risk of adverse selection. Informational asymmetries mean that assets become very important and that people without assets will find themselves credit constrained. Positive role of banks: maturity transformation; aggregation (bringing together small savings into a usable amount); risk pooling (default is a small part of the total).

5.5 Liqiudity risk

Banks face liquidity risk. A bank run is a risk in a fractional banking system. This has encouraged the development of lender of the last resort and deposit insurance. These schemes have to balance providing confidence and preventing moral hazard. Banks also face insolvency risk (asset with less than liabilities). Equity owners, depositor and money-market partners will be affected. Solvency problems can cause liquidity problems as banks become cautious about lending to each other. In the 1930s the Federal Reserve was passive towards banking failure; in 2015 the central bank learnt from the previous mistakes. However, there are limits. In Ireland the debts of the banking system were greater than the resources of the government. The relationship between the government and the central bank was highlighted during the European debt crisis of 2010.

References

Carlin, W., and D. Soskice. 2015. Macroeconomics: Institutioins, Instability, and the Financial System. 1st ed. OUP.

Kleimeier, S., and H. Sander. 2017. “Handbook of Competition in Banking and Finance.” In, edited by J.A. Bikker and L. Spierdijk, 305–433. Edward Elgar Publishing.