Chapter 4 Expectations

At the end of this chapter you should understand

Why economic agents form expectations

The use of Adaptive Expectations

The Rational Expectations hypothesis

The role of expectations in the New Keynesian model

The Lucas critique

Expectations

The formation of expectation is a key issue in macroeconomics. We have already had forward-looking households and firm making savings and investment decisions as well as central bank forecasting and decision-making.

4.1 Risk, uncertainty and expectations

Our discussion of expectations will bring together the ideas of uncertainty and risk. The distinction between uncertainty and risk is made by (Knight 1921) and (Keynes 1936). Risk can be quantified while uncertainty cannot. Some events have happened before and we have data that can be used to assess probabilities. The risk of death for people with particular age and other characteristics can be assessed for life insurance. However, the probability that an event like the collapse of the Berlin Wall will be seen is less easy to quantify. In the General Theory Keynes argues:

It is safe to say that enterprise which depends on hopes stretching into the future benefits the community as a whole. But individual initiative will only be adequate when reasonable calculation is supplemented and supported by animal spirits, so that the thought of ultimate loss which often overtakes pioneers, as experience undoubtedly tells us and them, is put aside as a healthy man puts aside the expectation of death.

We should not conclude from this that everything depends on waves of irrational psychology. On the contrary, the state of long-term expectation is often steady, and, even when it is not, the other factors exert their compensating effects. We are merely reminding ourselves that human decisions affecting the future, whether personal or political or economic, cannot depend on strict mathematical expectation, since the basis for making such calculations does not exist; and that it is our innate urge to activity which makes the wheels go round, our rational selves choosing between the alternatives as best we are able, calculating where we can, but often falling back for our motive on whim or sentiment or chance.

Keynes is suggesting that people use short-cuts to ease the difficulty of decision-making. Behavioura Economics builds on these ideas with psychological experiments about the ways that expectations are formed and the identification of these short-cuts or heuristics.

4.2 Models of expectations

There are two standard ways that expectations are modelled.

- Adaptive expectations. Expectations are largely based on what has happened in the past.

- Rational expectations. Expectations are based on the module that is being used by the economist.

You will notice that we have been using adaptive expectations for wage setting and price setting but rational expectations for the central bank. In coming chapters we will also suggest that international investors buying and selling foreign exchange are also using rational expectations to make decisions about the future. The rationale for these choices is that central banks and international investors spend a lot of time thinking about the future economy and the future direction of exchange rates, they employ economists and other experts to make predictions; regular people do not think so much about future inflation and have less incentive under normal conditions to get forecasts about inflation correct. These assumptions can, of course, be questioned. These are a simplification that can be justified on some occasions but not others. Rational expectations tend to rule out the development of speculative bubbles that appear to have been an important part of the Global Financial Crisis.

4.3 Phillips curve and expectations

Inflation expectations

\[E(\pi_t | \theta_{t-1}) \equiv \pi_t^E\]

Expected inflation is based on past information. As the agents have all the information up to \(t_1\), this means that only random shocks can bring a surprise to inflation. The Phillips curve will depend on the way that inflation expectations are modelled. The standard curve is

\[\pi_t = \pi_t^E + \alpha(y_t - y_e)\]

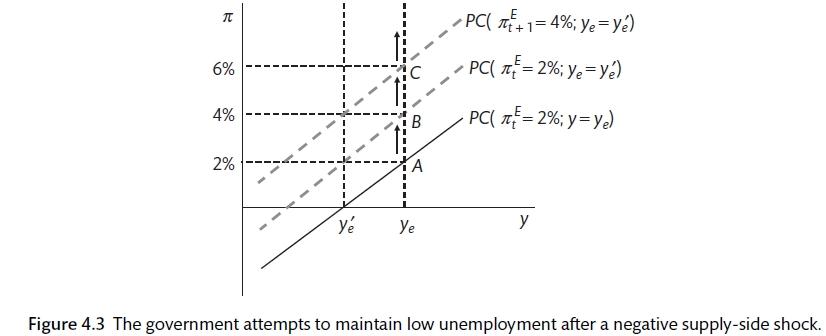

What do we know about inflation? Figure 4.2 shows the evolution of inflation. There are different regimes: from 1801 to 1916 inflation was volatility around zero; the 1930s and 40s were more volatile; the 1950s and 60s were positive and the 1970s and 1980s had high inflation; the final period s one of deflation. The 1950s and 1960s can be seen against the backdrop of the 1930s and the Keynesian revolution. Supply-side changes in the 1950s and 1960s means that the underling rate of unemployment increased and the trade off between unemployment and inflation changed: there was a shift in bargaining power towards workers (an upward shift in the WS curve), a fall in productivity caused by an end to the Fordist against in the production line (a downward shift in the PS curve). Figure 4.1 shows this change: the equilibrium output \((y_e)\) level and the Phillips curve (relationship between output and inflation) will change. With adaptive expectations being updated for the last increase in inflation, there can be an upward spiral in inflation.

Adaptive expectations and the inflationary spiral (Carlin and Soskice 2015)

(Friedman 1968) and (Phelps 1968) argued that the Phillips curve was vertical in the long-run and that an increase in employment beyond that connected with the natural rate would just cause inflation expectations and inflation to rise. They short-run Phillips curve, they argued, was determined by the level of inflation expectations. There is a discussion of Friedman, Phelps and the evolution of macroeconomic models here

\[\pi_t^E = \pi_{t-1} + \alpha (y_t - y_s)\]

The equation can be re-arranged to show how inflation changes.

\[\pi_t - \pi_{t-1} = \Delta pi = \alpha(y_t - y_e)\]

Therefore the relationship between unemployment and inflation will hold only as long as the government does not try to run the economy above the equilibrium level of output.

The rational expectations framework suggests that agents can learn. They understand the model that is being used. They do not make systematic mistakes. In the rational expectations framework, it is only unsystematic shocks that cause inflation to differ from expectations.

\[\pi_t = \pi_t^E + \alpha(y_t - y_s) + \varepsilon_t\]

Therefore,

\[y_t = y_s - \frac{\varepsilon_t}{\alpha}\]

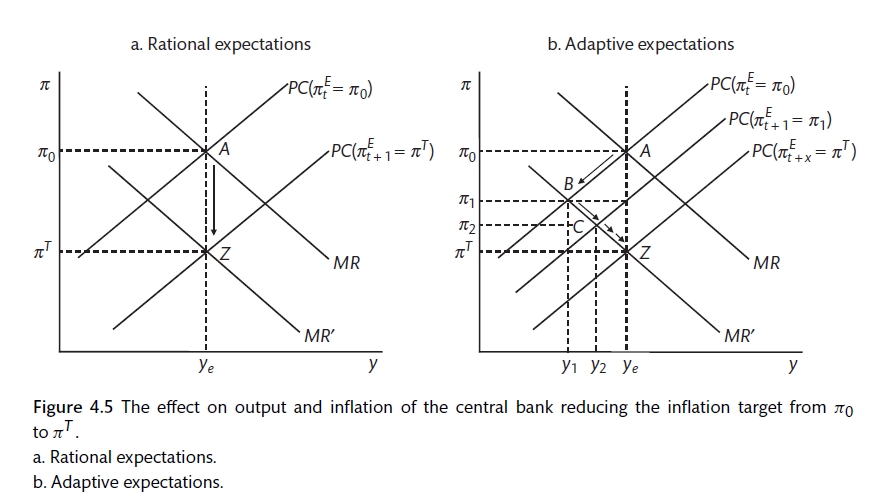

The difference between adaptive expectations and rational expectations. If the central bank wants to reduce the inflation target in conditions where expectations are formed adaptively, it will increase interest rates to reduce output below the stabilising rate so that inflation expectations are pushed lower. There is an output-employment cost to reducing inflation. If expectations are formed rationally, changing the rate of inflation is more rapid and less painful.

Central bank policy under rational and adaptive expectations (Carlin and Soskice 2015)

With rational expectations, agents believe that inflation will be at the target apart from a random, non-systematic element. In this case, the central bank will keep output at the stabilising rate and agents adjust their inflation expectations to the new target. The three major differences between an economy that is largely working under rational expectations from one where expectation arise adaptively are:

- the economy remains at equilibrium apart from the random shocks;

- there is no inbuilt method for inflationary or deflationary forces to arise;

- the central bank does not have to worry about forecasts and lags;

- since wage-setters and price-setters are forward-looking, the central bank can influence expectations directly.

4.4 Central bank expectations policy

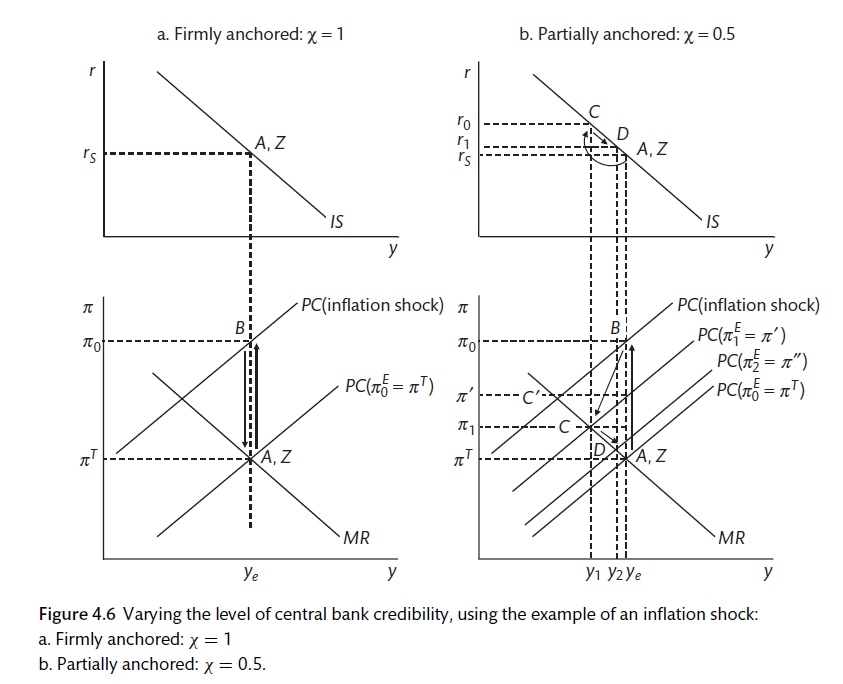

There is a huge amount of central bank effort devoted to managing expectations. If the central bank intentions are known and credible, an inflation shock is a one-period shock that should not change expectations. If inflation expectations are anchored, there is no need for a painful adjustment that involves unemployment. This idea can be captured by modifying the adaptive expectations Phillips curve to incorporate credibility with expectations formed as a weighted sum of the inflation target and lagged inflation. \((\chi)\) determines the weight to credibility.

\[\pi_t = \chi \pi^T + (1 - \chi) \pi_{t-1} + \alpha(y_t - y_s)\]

\[\pi^T_t = \chi \pi^T + (1 - \chi) \pi_{t-1}\]

The two extremes are \(\chi = 1\) where inflation expectations are fully anchored to \(\chi = 0\) where expectations are adaptive. The more credibility that the central bank has the lower the cost of maintaining the target. Two major factors affect credibility: communication and transparency. The communication strategies of the central bank seek to address the questions that may arise: will the central bank stick to the target; can the central bank shape inflation expectations? These factors depend on the independence of the central bank from political pressure, as well as history, culture and other institutions. In addition, the more transparent central bank decision-making and objectives, the less chance of a surprise.

Central bank credibility (Carlin and Soskice 2015)

Therefore, if the central bank has credibility it becomes much easier and less painful (in terms of unemployment) to reduce inflation. For many years it was argued that the credibility of the German central bank (the Bundesbank) was part of the reason for the stability and success of the German economy. The creation of the Euro and the Eurozone was at least partly an attempt to extend this credibility to other European nations. Now it appears that credibility may have gone too far. Most people do not remember inflation. People do not expect inflation to be above 2.0%.

4.5 The Lucas critique

New Classical Economics has developed since the 1970s. This is based on formal microfoundations where agents have forward-looking, model-consistent expectations. Real Business Cycle economics is the result. The Lucas Critique (Lucas 1976) says that economic relationships will change when policy regimes change because economic agents will adapt their behaviour. If agents are set expectations rationally, it is not possible for the government to engineer a one-off increase in output (ahead of an election). Inflation expectations remain anchored. A government controlled central bank would not have the same effect. Now inflation expectations would rise with the increase in government spending and a more painful process would be required to bring it back down. Similarly, if we assume rational expectations, a cut in the inflation target can be made without any pain. Therefore, the use of rational expectations is controversial and at the extreme can suggest that the government has no positive influence over the economy.

References

Carlin, W., and D. Soskice. 2015. Macroeconomics: Institutioins, Instability, and the Financial System. 1st ed. OUP.

Friedman, M. 1968. “The Role of Monetary Policy.” The American Economic Review 58 (1): 1–17.

Keynes, John Maynard. 1936. The General Theory of Employment, Money and Interest. Macmillan.

Knight, F. 1921. Risk, Uncertainty and Profit. Houghton Mifflin, Boston.

Lucas, R. E. jr. 1976. “Econometric Policy Evaluation: A Critique.” Carnegie-Rochester Conference Series on Public Policy 1 (0): 19–46.

Phelps, E.S. 1968. “Phillips Curves, Expectations of Inflation and Optimal Monetary Policy over Time.” Economica 34 (135): 254–81.