Chapter 13 Geomarketing

Note: this is the first edition of Geocomputation with R, first published in 2019 and with minor updates since then until summer 2021. For the Second Edition of Geocomputation with R, due for publication in 2022, see geocompr.robinlovelace.net.

Prerequisites

- This chapter requires the following packages (revgeo must also be installed):

library(sf)

library(dplyr)

library(purrr)

library(raster)

library(osmdata)

library(spDataLarge)- Required data, that will be downloaded in due course

As a convenience to the reader and to ensure easy reproducibility, we have made available the downloaded data in the spDataLarge package.

13.1 Introduction

This chapter demonstrates how the skills learned in Parts I and II can be applied to a particular domain: geomarketing (sometimes also referred to as location analysis or location intelligence). This is a broad field of research and commercial application. A typical example is where to locate a new shop. The aim here is to attract most visitors and, ultimately, make the most profit. There are also many non-commercial applications that can use the technique for public benefit, for example where to locate new health services (Tomintz, Clarke, and Rigby 2008).

People are fundamental to location analysis, in particular where they are likely to spend their time and other resources. Interestingly, ecological concepts and models are quite similar to those used for store location analysis. Animals and plants can best meet their needs in certain ‘optimal’ locations, based on variables that change over space (Muenchow et al. (2018); see also chapter 14). This is one of the great strengths of geocomputation and GIScience in general. Concepts and methods are transferable to other fields. Polar bears, for example, prefer northern latitudes where temperatures are lower and food (seals and sea lions) is plentiful. Similarly, humans tend to congregate in certain places, creating economic niches (and high land prices) analogous to the ecological niche of the Arctic. The main task of location analysis is to find out where such ‘optimal locations’ are for specific services, based on available data. Typical research questions include:

- Where do target groups live and which areas do they frequent?

- Where are competing stores or services located?

- How many people can easily reach specific stores?

- Do existing services over- or under-exploit the market potential?

- What is the market share of a company in a specific area?

This chapter demonstrates how geocomputation can answer such questions based on a hypothetical case study based on real data.

13.2 Case study: bike shops in Germany

Imagine you are starting a chain of bike shops in Germany. The stores should be placed in urban areas with as many potential customers as possible. Additionally, a hypothetical survey (invented for this chapter, not for commercial use!) suggests that single young males (aged 20 to 40) are most likely to buy your products: this is the target audience. You are in the lucky position to have sufficient capital to open a number of shops. But where should they be placed? Consulting companies (employing geomarketing analysts) would happily charge high rates to answer such questions. Luckily, we can do so ourselves with the help of open data and open source software. The following sections will demonstrate how the techniques learned during the first chapters of the book can be applied to undertake common steps in service location analysis:

- Tidy the input data from the German census (Section 13.3)

- Convert the tabulated census data into raster objects (Section 13.4)

- Identify metropolitan areas with high population densities (Section 13.5)

- Download detailed geographic data (from OpenStreetMap, with osmdata) for these areas (Section 13.6)

- Create rasters for scoring the relative desirability of different locations using map algebra (Section 13.7)

Although we have applied these steps to a specific case study, they could be generalized to many scenarios of store location or public service provision.

13.3 Tidy the input data

The German government provides gridded census data at either 1 km or 100 m resolution.

The following code chunk downloads, unzips and reads in the 1 km data.

Please note that census_de is also available from the spDataLarge package (data("census_de", package = "spDataLarge").

download.file("https://tinyurl.com/ybtpkwxz",

destfile = "census.zip", mode = "wb")

unzip("census.zip") # unzip the files

census_de = readr::read_csv2(list.files(pattern = "Gitter.csv"))The census_de object is a data frame containing 13 variables for more than 300,000 grid cells across Germany.

For our work, we only need a subset of these: Easting (x) and Northing (y), number of inhabitants (population; pop), mean average age (mean_age), proportion of women (women) and average household size (hh_size).

These variables are selected and renamed from German into English in the code chunk below and summarized in Table 13.1.

Further, mutate_all() is used to convert values -1 and -9 (meaning unknown) to NA.

# pop = population, hh_size = household size

input = dplyr::select(census_de, x = x_mp_1km, y = y_mp_1km, pop = Einwohner,

women = Frauen_A, mean_age = Alter_D,

hh_size = HHGroesse_D)

# set -1 and -9 to NA

input_tidy = mutate_all(input, list(~ifelse(. %in% c(-1, -9), NA, .)))| class | Population | % female | Mean age | Household size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3-250 | 0-40 | 0-40 | 1-2 |

| 2 | 250-500 | 40-47 | 40-42 | 2-2.5 |

| 3 | 500-2000 | 47-53 | 42-44 | 2.5-3 |

| 4 | 2000-4000 | 53-60 | 44-47 | 3-3.5 |

| 5 | 4000-8000 | >60 | >47 | >3.5 |

| 6 | >8000 |

13.4 Create census rasters

After the preprocessing, the data can be converted into a raster stack or brick (see Sections 2.3.3 and 3.3.1).

rasterFromXYZ() makes this really easy.

It requires an input data frame where the first two columns represent coordinates on a regular grid.

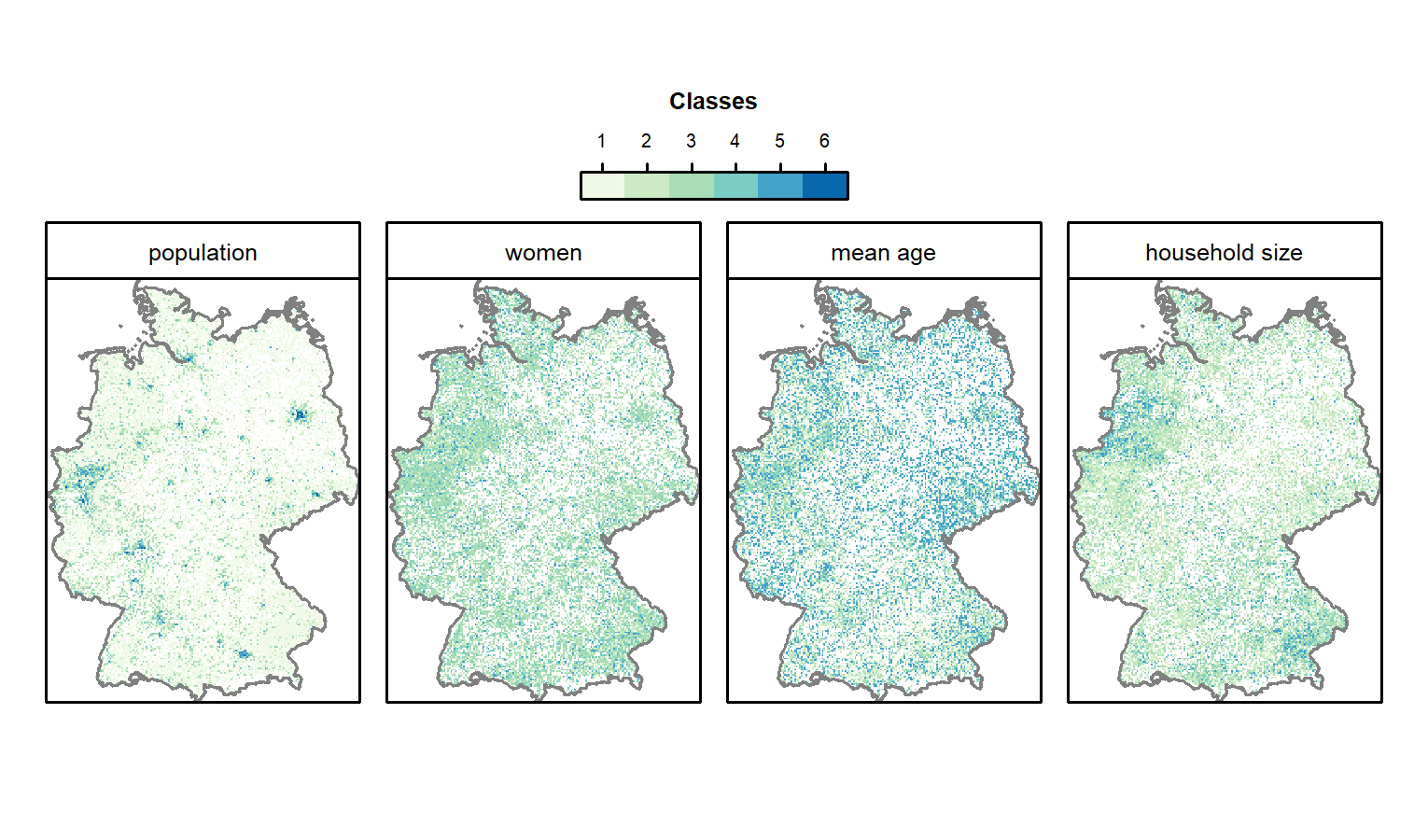

All the remaining columns (here: pop, women, mean_age, hh_size) will serve as input for the raster brick layers (Figure 13.1; see also code/13-location-jm.R in our github repository).

input_ras = rasterFromXYZ(input_tidy, crs = st_crs(3035)$proj4string)input_ras

#> class : RasterBrick

#> dimensions : 868, 642, 557256, 4 (nrow, ncol, ncell, nlayers)

#> resolution : 1000, 1000 (x, y)

#> extent : 4031000, 4673000, 2684000, 3552000 (xmin, xmax, ymin, ymax)

#> coord. ref. : +proj=laea +lat_0=52 +lon_0=10

#> names : pop, women, mean_age, hh_size

#> min values : 1, 1, 1, 1

#> max values : 6, 5, 5, 5

FIGURE 13.1: Gridded German census data of 2011 (see Table 13.1 for a description of the classes).

The next stage is to reclassify the values of the rasters stored in input_ras in accordance with the survey mentioned in Section 13.2, using the raster function reclassify(), which was introduced in Section 4.3.3.

In the case of the population data, we convert the classes into a numeric data type using class means.

Raster cells are assumed to have a population of 127 if they have a value of 1 (cells in ‘class 1’ contain between 3 and 250 inhabitants) and 375 if they have a value of 2 (containing 250 to 500 inhabitants), and so on (see Table 13.1).

A cell value of 8000 inhabitants was chosen for ‘class 6’ because these cells contain more than 8000 people.

Of course, these are approximations of the true population, not precise values.75

However, the level of detail is sufficient to delineate metropolitan areas (see next section).

In contrast to the pop variable, representing absolute estimates of the total population, the remaining variables were re-classified as weights corresponding with weights used in the survey.

Class 1 in the variable women, for instance, represents areas in which 0 to 40% of the population is female;

these are reclassified with a comparatively high weight of 3 because the target demographic is predominantly male.

Similarly, the classes containing the youngest people and highest proportion of single households are reclassified to have high weights.

rcl_pop = matrix(c(1, 1, 127, 2, 2, 375, 3, 3, 1250,

4, 4, 3000, 5, 5, 6000, 6, 6, 8000),

ncol = 3, byrow = TRUE)

rcl_women = matrix(c(1, 1, 3, 2, 2, 2, 3, 3, 1, 4, 5, 0),

ncol = 3, byrow = TRUE)

rcl_age = matrix(c(1, 1, 3, 2, 2, 0, 3, 5, 0),

ncol = 3, byrow = TRUE)

rcl_hh = rcl_women

rcl = list(rcl_pop, rcl_women, rcl_age, rcl_hh)Note that we have made sure that the order of the reclassification matrices in the list is the same as for the elements of input_ras.

For instance, the first element corresponds in both cases to the population.

Subsequently, the for-loop applies the reclassification matrix to the corresponding raster layer.

Finally, the code chunk below ensures the reclass layers have the same name as the layers of input_ras.

reclass = input_ras

for (i in seq_len(nlayers(reclass))) {

reclass[[i]] = reclassify(x = reclass[[i]], rcl = rcl[[i]], right = NA)

}

names(reclass) = names(input_ras)reclass

#> ... (full output not shown)

#> names : pop, women, mean_age, hh_size

#> min values : 127, 0, 0, 0

#> max values : 8000, 3, 3, 313.5 Define metropolitan areas

We define metropolitan areas as pixels of 20 km2 inhabited by more than 500,000 people.

Pixels at this coarse resolution can rapidly be created using aggregate(), as introduced in Section 5.3.3.

The command below uses the argument fact = 20 to reduce the resolution of the result twenty-fold (recall the original raster resolution was 1 km2):

pop_agg = aggregate(reclass$pop, fact = 20, fun = sum)The next stage is to keep only cells with more than half a million people.

summary(pop_agg)

#> pop

#> Min. 127

#> 1st Qu. 39886

#> Median 66008

#> 3rd Qu. 105696

#> Max. 1204870

#> NA's 447

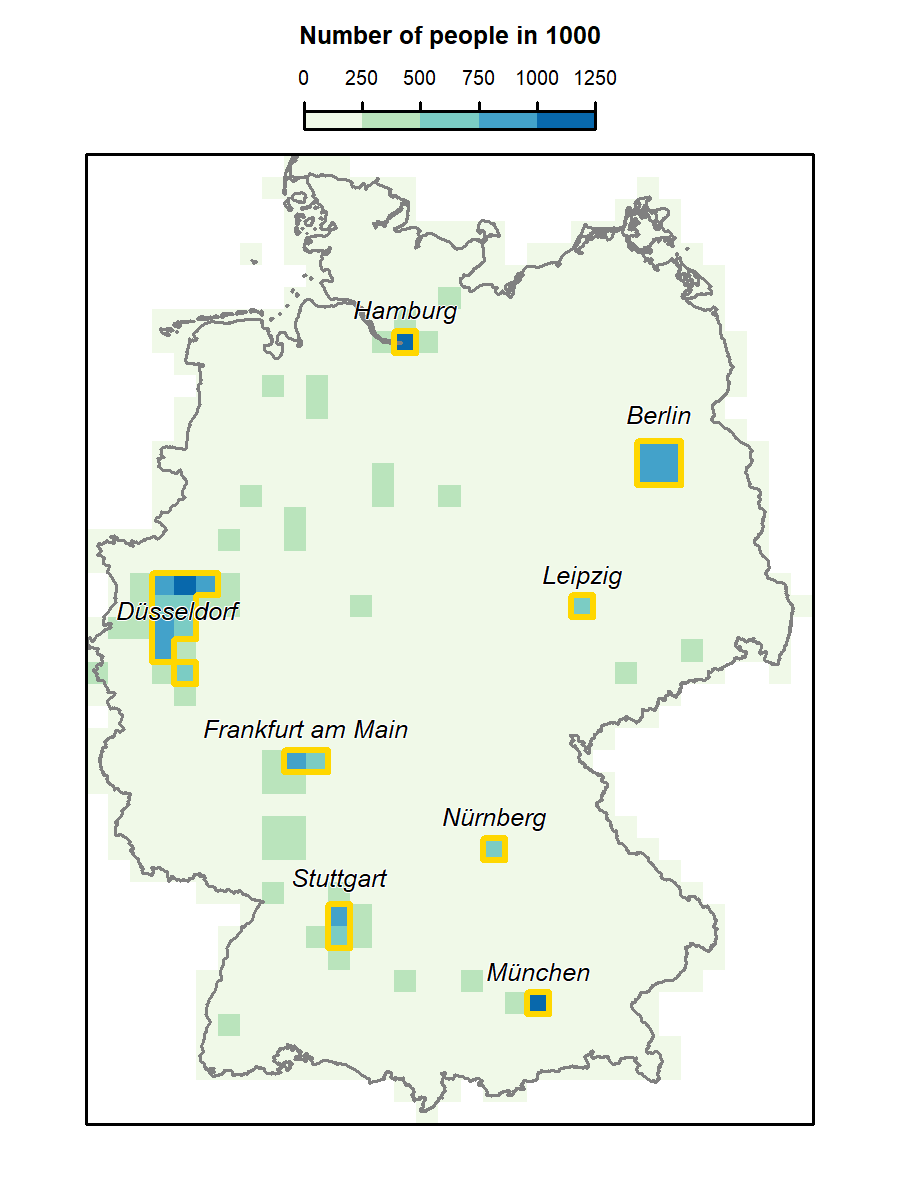

pop_agg = pop_agg[pop_agg > 500000, drop = FALSE] Plotting this reveals eight metropolitan regions (Figure 13.2).

Each region consists of one or more raster cells.

It would be nice if we could join all cells belonging to one region.

raster’s clump() command does exactly that.

Subsequently, rasterToPolygons() converts the raster object into spatial polygons, and st_as_sf() converts it into an sf-object.

polys = pop_agg %>%

clump() %>%

rasterToPolygons() %>%

st_as_sf()polys now features a column named clumps which indicates to which metropolitan region each polygon belongs and which we will use to dissolve the polygons into coherent single regions (see also Section 5.2.6):

metros = polys %>%

group_by(clumps) %>%

summarize()Given no other column as input, summarize() only dissolves the geometry.

FIGURE 13.2: The aggregated population raster (resolution: 20 km) with the identified metropolitan areas (golden polygons) and the corresponding names.

The resulting eight metropolitan areas suitable for bike shops (Figure 13.2; see also code/13-location-jm.R for creating the figure) are still missing a name.

A reverse geocoding approach can settle this problem.

Given a coordinate, reverse geocoding finds the corresponding address.

Consequently, extracting the centroid coordinate of each metropolitan area can serve as an input for a reverse geocoding API.

The revgeo package provides access to the open source Photon geocoder for OpenStreetMap, Google Maps and Bing.

By default, it uses the Photon API.

revgeo::revgeo() only accepts geographical coordinates (latitude/longitude); therefore, the first requirement is to bring the metropolitan polygons into an appropriate coordinate reference system (Chapter 6).

metros_wgs = st_transform(metros, 4326)

coords = st_centroid(metros_wgs) %>%

st_coordinates() %>%

round(4)Choosing frame as revgeocode()’s output option will give back a data.frame with several columns referring to the location including the street name, house number and city.

library(revgeo)

metro_names = revgeo(longitude = coords[, 1], latitude = coords[, 2],

output = "frame")To make sure that the reader uses the exact same results, we have put them into spDataLarge as the object metro_names.

| city | state |

|---|---|

| Hamburg | Hamburg |

| Berlin | Berlin |

| Wülfrath | North Rhine-Westphalia |

| Leipzig | Saxony |

| Frankfurt am Main | Hesse |

| Nuremberg | Bavaria |

| Stuttgart | Baden-Württemberg |

| Munich | Bavaria |

Overall, we are satisfied with the city column serving as metropolitan names (Table 13.2) apart from one exception, namely Wülfrath which belongs to the greater region of Düsseldorf.

Hence, we replace Wülfrath with Düsseldorf (Figure 13.2).

Umlauts like ü might lead to trouble further on, for example when determining the bounding box of a metropolitan area with opq() (see further below), which is why we avoid them.

metro_names = dplyr::pull(metro_names, city) %>%

as.character() %>%

ifelse(. == "Wülfrath", "Duesseldorf", .)13.6 Points of interest

The osmdata package provides easy-to-use access to OSM data (see also Section 7.2). Instead of downloading shops for the whole of Germany, we restrict the query to the defined metropolitan areas, reducing computational load and providing shop locations only in areas of interest. The subsequent code chunk does this using a number of functions including:

map()(the tidyverse equivalent oflapply()), which iterates through all eight metropolitan names which subsequently define the bounding box in the OSM query functionopq()(see Section 7.2).add_osm_feature()to specify OSM elements with a key value ofshop(see wiki.openstreetmap.org for a list of common key:value pairs).osmdata_sf(), which converts the OSM data into spatial objects (of classsf).while(), which tries repeatedly (three times in this case) to download the data if it fails the first time.76 Before running this code: please consider it will download almost 2GB of data. To save time and resources, we have put the output namedshopsinto spDataLarge. To make it available in your environment ensure that the spDataLarge package is loaded, or rundata("shops", package = "spDataLarge").

shops = map(metro_names, function(x) {

message("Downloading shops of: ", x, "\n")

# give the server a bit time

Sys.sleep(sample(seq(5, 10, 0.1), 1))

query = opq(x) %>%

add_osm_feature(key = "shop")

points = osmdata_sf(query)

# request the same data again if nothing has been downloaded

iter = 2

while (nrow(points$osm_points) == 0 & iter > 0) {

points = osmdata_sf(query)

iter = iter - 1

}

points = st_set_crs(points$osm_points, 4326)

})It is highly unlikely that there are no shops in any of our defined metropolitan areas.

The following if condition simply checks if there is at least one shop for each region.

If not, we recommend to try to download the shops again for this/these specific region/s.

# checking if we have downloaded shops for each metropolitan area

ind = map(shops, nrow) == 0

if (any(ind)) {

message("There are/is still (a) metropolitan area/s without any features:\n",

paste(metro_names[ind], collapse = ", "), "\nPlease fix it!")

}To make sure that each list element (an sf data frame) comes with the same columns, we only keep the osm_id and the shop columns with the help of another map loop.

This is not a given since OSM contributors are not equally meticulous when collecting data.

Finally, we rbind all shops into one large sf object.

# select only specific columns

shops = map(shops, dplyr::select, osm_id, shop)

# putting all list elements into a single data frame

shops = do.call(rbind, shops)It would have been easier to simply use map_dfr().

Unfortunately, so far it does not work in harmony with sf objects.

Note: shops is provided in the spDataLarge package.

The only thing left to do is to convert the spatial point object into a raster (see Section 5.4.3).

The sf object, shops, is converted into a raster having the same parameters (dimensions, resolution, CRS) as the reclass object.

Importantly, the count() function is used here to calculate the number of shops in each cell.

shop column were used instead of the osm_id column, we would have retrieved fewer shops per grid cell.

This is because the shop column contains NA values, which the count() function omits when rasterizing vector objects.

The result of the subsequent code chunk is therefore an estimate of shop density (shops/km2).

st_transform() is used before rasterize() to ensure the CRS of both inputs match.

shops = st_transform(shops, proj4string(reclass))

# create poi raster

poi = rasterize(x = shops, y = reclass, field = "osm_id", fun = "count")As with the other raster layers (population, women, mean age, household size) the poi raster is reclassified into four classes (see Section 13.4).

Defining class intervals is an arbitrary undertaking to a certain degree.

One can use equal breaks, quantile breaks, fixed values or others.

Here, we choose the Fisher-Jenks natural breaks approach which minimizes within-class variance, the result of which provides an input for the reclassification matrix.

# construct reclassification matrix

int = classInt::classIntervals(values(poi), n = 4, style = "fisher")

int = round(int$brks)

rcl_poi = matrix(c(int[1], rep(int[-c(1, length(int))], each = 2),

int[length(int)] + 1), ncol = 2, byrow = TRUE)

rcl_poi = cbind(rcl_poi, 0:3)

# reclassify

poi = reclassify(poi, rcl = rcl_poi, right = NA)

names(poi) = "poi"13.7 Identifying suitable locations

The only steps that remain before combining all the layers are to add poi to the reclass raster stack and remove the population layer from it.

The reasoning for the latter is twofold.

First of all, we have already delineated metropolitan areas, that is areas where the population density is above average compared to the rest of Germany.

Second, though it is advantageous to have many potential customers within a specific catchment area, the sheer number alone might not actually represent the desired target group.

For instance, residential tower blocks are areas with a high population density but not necessarily with a high purchasing power for expensive cycle components.

This is achieved with the complementary functions addLayer() and dropLayer():

# add poi raster

reclass = addLayer(reclass, poi)

# delete population raster

reclass = dropLayer(reclass, "pop")In common with other data science projects, data retrieval and ‘tidying’ have consumed much of the overall workload so far. With clean data, the final step — calculating a final score by summing all raster layers — can be accomplished in a single line of code.

# calculate the total score

result = sum(reclass)For instance, a score greater than 9 might be a suitable threshold indicating raster cells where a bike shop could be placed (Figure 13.3; see also code/13-location-jm.R).

FIGURE 13.3: Suitable areas (i.e., raster cells with a score > 9) in accordance with our hypothetical survey for bike stores in Berlin.

13.8 Discussion and next steps

The presented approach is a typical example of the normative usage of a GIS (P. Longley 2015). We combined survey data with expert-based knowledge and assumptions (definition of metropolitan areas, defining class intervals, definition of a final score threshold). This approach is less suitable for scientific research than applied analysis that provides an evidence based indication of areas suitable for bike shops that should be compared with other sources of information. A number of changes to the approach could improve the analysis:

- We used equal weights when calculating the final scores but other factors, such as the household size, could be as important as the portion of women or the mean age

- We used all points of interest but only those related to bike shops, such as do-it-yourself, hardware, bicycle, fishing, hunting, motorcycles, outdoor and sports shops (see the range of shop values available on the OSM Wiki) may have yielded more refined results

- Data at a higher resolution may improve the output (see exercises)

- We have used only a limited set of variables and data from other sources, such as the INSPIRE geoportal or data on cycle paths from OpenStreetMap, may enrich the analysis (see also Section 7.2)

- Interactions remained unconsidered, such as a possible relationships between the portion of men and single households

In short, the analysis could be extended in multiple directions. Nevertheless, it should have given you a first impression and understanding of how to obtain and deal with spatial data in R within a geomarketing context.

Finally, we have to point out that the presented analysis would be merely the first step of finding suitable locations. So far we have identified areas, 1 by 1 km in size, representing potentially suitable locations for a bike shop in accordance with our survey. Subsequent steps in the analysis could be taken:

- Find an optimal location based on number of inhabitants within a specific catchment area. For example, the shop should be reachable for as many people as possible within 15 minutes of traveling bike distance (catchment area routing). Thereby, we should account for the fact that the further away the people are from the shop, the more unlikely it becomes that they actually visit it (distance decay function).

- Also it would be a good idea to take into account competitors. That is, if there already is a bike shop in the vicinity of the chosen location, one has to distribute possible customers (or sales potential) between the competitors (Huff 1963; Wieland 2017).

- We need to find suitable and affordable real estate, e.g., in terms of accessibility, availability of parking spots, desired frequency of passers-by, having big windows, etc.

13.9 Exercises

We have used

raster::rasterFromXYZ()to convert ainput_tidyinto a raster brick. Try to achieve the same with the help of thesp::gridded()function.Download the csv file containing inhabitant information for a 100-m cell resolution (https://www.zensus2011.de/SharedDocs/Downloads/DE/Pressemitteilung/DemografischeGrunddaten/csv_Bevoelkerung_100m_Gitter.zip?__blob=publicationFile&v=3). Please note that the unzipped file has a size of 1.23 GB. To read it into R, you can use

readr::read_csv. This takes 30 seconds on my machine (16 GB RAM)data.table::fread()might be even faster, and returns an object of classdata.table(). Useas.tibble()to convert it into a tibble. Build an inhabitant raster, aggregate it to a cell resolution of 1 km, and compare the difference with the inhabitant raster (inh) we have created using class mean values.Suppose our bike shop predominantly sold electric bikes to older people. Change the age raster accordingly, repeat the remaining analyses and compare the changes with our original result.