7 ESG Investing

ESG stands for Environmental, Social, and Governance, which is perhaps the broader umbrella for socially repsonsible investing, or SRI. Generally speaking, people use the term SRI when thinking about investing that reflects a certain set of values. ESG is broader and about incorporating a wide range of information about different stakeholders into the investment process. This is sometimes called stakeholder capitalism.

But what stakeholders? And whose values? This gets complicated fast.When we teach introductory finance, as well as AMF, we introduce the idea of shareholder value maximization. Is there another way? Should firms just care about their stock price? Have firms ever just cared about their stock price?

This could be (and, in fact, is) a topic for an entire semester’s worth of content. In fact, Elon is in the process of creating a sustainability minor. So, I’ll just point you to some work on this that says “Yes, it is fine for firms to take into account shareholder preferences beyond just stock price maximization.”18 One way for shareholder preferences to become incorporated into firm decisions is via more shareholder Democracy (i.e. voting).

These notes are based on CFA readings and my understanding of the latest research in the area. I start with an overview of investment process, how people are thinking about ESG investing, and what’s been happening recently.

I then cover what the academic research says about ESG. We’ll briefly review how ESG funds make decisions, what their performance is like (and why), how ESG investing affects the firms themselves, and whether or not ESG investing has a “real” impact.

This type of investing has been around a while, but there’s a lot of uncertainty around the process, as well as definitions that aren’t very clear. To me, this means that there are a lot of opportunities to improve things.

The CFA Institute has an entire page dedicated to ESG investing, to give you a sense of how important this has become. They also have a new certificate in ESG investing. The certificate is from the UK CFA Society – ESG investing has arguably taken off faster in Europe than in the U.S.

Figure 7.1: New CFA certificate on ESG investing. Source: CFA Institute

See the overview by Pedro Matos for the CFA Institute (posted on Moodle) if you’d like a comprehensive overview of where things currently stand.

Finally, I am going to focus on public equities. There is also ESG-style investing in bonds, private equity and credit, real estate, etc.

7.1 An Overview

ESG investing is about taking into account non-financial information, such as environmental impact (E), worker safety(S), and board structure (G), when making investment decisions. This gets at a topic as old as finance and economics: what is the purpose of a firm? Is it to make profits? Is it something bigger? Should it be something bigger? What should shareholders care about?

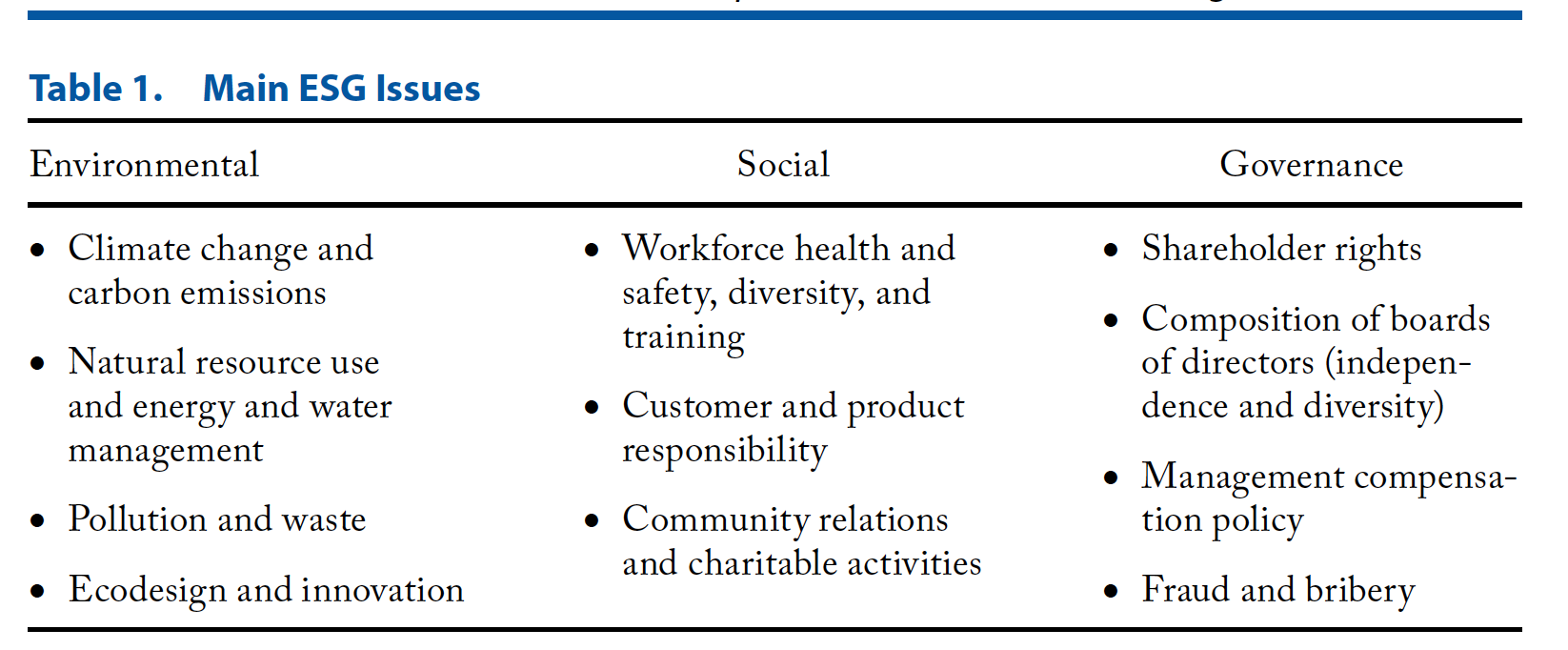

Figure 7.2: What issues do we face in ESG investing? Source: CFA Institute (2020)

The “E” part is perhaps the most obvious and deals with things like carbon emissions, use of natural resources, waste, and product design. The “S” details efforts to improve employee relations and just being a good corporate citizen. The “G” is about the mechanisms in place for the firm to act in the best interest of long-term shareholders, such as limiting anti-takeover measures and have an independent board. This also might mean avoiding illegal practices, like paying bribes.

As mentioned, though, the biggest effort is around carbon emissions, coming costs and regulations, and the impact of warming on the firm itself. For example, does a real estate firm own a lot of property in Miami? Or, where might changing climate affect of firm’s supply chain if it relies on a lot of rare earth metals? We want to know if these risks are being correctly priced in.

We are going to focus on the investing side and the methods and products that are out there. You can also think about things from the corporate finance side, where the firm’s management wants to consider issues beyond profits. You can also think about things from governments’ perspective, since they are the ones who make the regulations and try to deal with the externalities caused by undersirable firm behavior. Optimal government policy is obviously a huge and important topic.

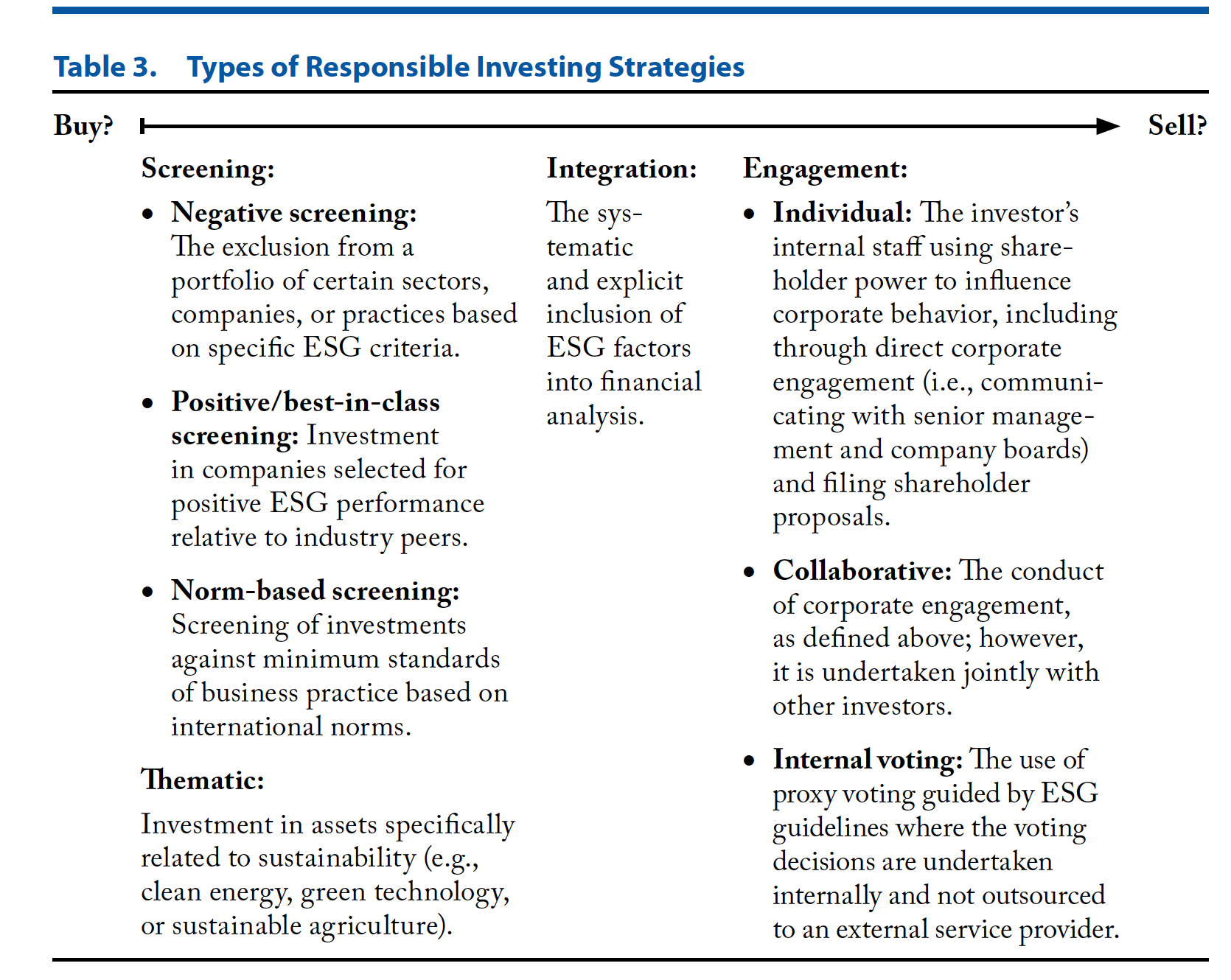

Figure 7.3: What is ESG investing anyway? Source: CFA Institute (2020)

We want to ask ourselves: What are investors doing and, perhaps, what should investors do in order to use ESG ideas They might use these ideas either from a desire to better value firms or to incorporate their personal values (or the values of their investors) into the process? From the Matos (2020) summary published by the CFA institute, there are three main issues in ESG right now:

There is no consenus on the exact list of ESG issues and their materiality. For example, how should investors weigh carbon and paying a living wage?

That said, climate change is the big issue. Investors want to know which firms have exposure to carbon risk and “stranded assets” that might now be worth anything a decade or two from now.

Investors should be ready for increased regulation (and carbon pricing), especially in the EU.

How important is ESG investing? At least one estimate has that $30 trillion of assets globally are managed with at least some kind of ESG mandate as of 2018, with $12 trillion of that in the U.S. (CFA Institute). The Principles for Responsible Investment (PRI) have 2,500 investment firms who manage over $85 trillion committed to ESG ideas. So, there are very large institutional pools of assets who say they want to do this.

The demand seems smaller at the retail level, though investment firms are ready for what they believe will be a rapid increase in demand for ESG products. There are less than $1 trillion in mutual fund and ETF assets being managed as an ESG product (CFA Institute).

There is an effort to create custom ESG indices for individual investors, as part of the growing trend of direct indexing for larger accounts.

Do ESG events affect firm value, outside of any value judgement? If we take each letter seriously, then the 2001 Enron accounting fraud, the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill, the 2015 VW emissions test scandel, and the connections between Facebook and Cambridge Analytics are all ESG-related events that negatively impacted firm value. Enron went to zero. Facebook trades a relative discount to other tech firms. I’ll mention some evidence below that says that we should take ESG seriously when thinking about firm risk, above and beyond any broader concerns.

A lot of ESG investing is based on work done by third-parties, such as MSCI. They will rank firms according to their own ESG criteria and then put together a list of high and low ESG firms.19 For example, MSCI creates a commonly-used index of ESG stocks called the MSCI KLD 400 Social Index. You can invest in this index as an ETF product via Blackrock’s iShares.

Figure 7.4: These are large investment firms and asset owners that say they will follow certain ESG guidelines. Source: CFA Institute (2020)

Blackrock, Vanguard, State STreet, MSCI, and the other large institutional investors and index providers get a lot of the headlines. Figure 7.4 lists some of the large investment firms that have pledged to follow ESG guidelines. More from the Lexington FT column (3/10/21):

BlackRock, which has shifted its ESG stance from mysterious assenter to enthusiastic proponent, will raise the proportion of its funds committed to sustainable investing. Last year 62 per cent of its fund launches met EU guidelines on ESG principles. This year that proportion (in Europe) will be 70 per cent. But only 17 per cent of outstanding assets under management covered by the new requirement ($410bn of $2.5tn) met the target last year. BlackRock still has plenty of work to do.

The world’s biggest asset manager wants to scoop up as much ESG inflows as possible. These have become a torrent. In the three years to end-2020, money coming in has grown at a quarterly compound rate of 18 per cent in Europe, according to Morningstar. The rate of increase is even faster in the US, though from a smaller base. More than 82 per cent of sustainable fund assets are Europe-based according to Morningstar.

Bogus claims abound in the world of ESG. Revealingly, the largest weighted constituents of MSCI’s World ESG Leaders are very similar to those of its regular world equities index. It is time for the authorities to police the green claims of fund managers as tightly as their projections on investment returns.

Blackrock, Vanguard, Japan’s Government Pension Investment Fund (GPIF), and Norges Bank Investment Management (NBIM) are all massive pools of capital and have announced ESG goals in the last decade.

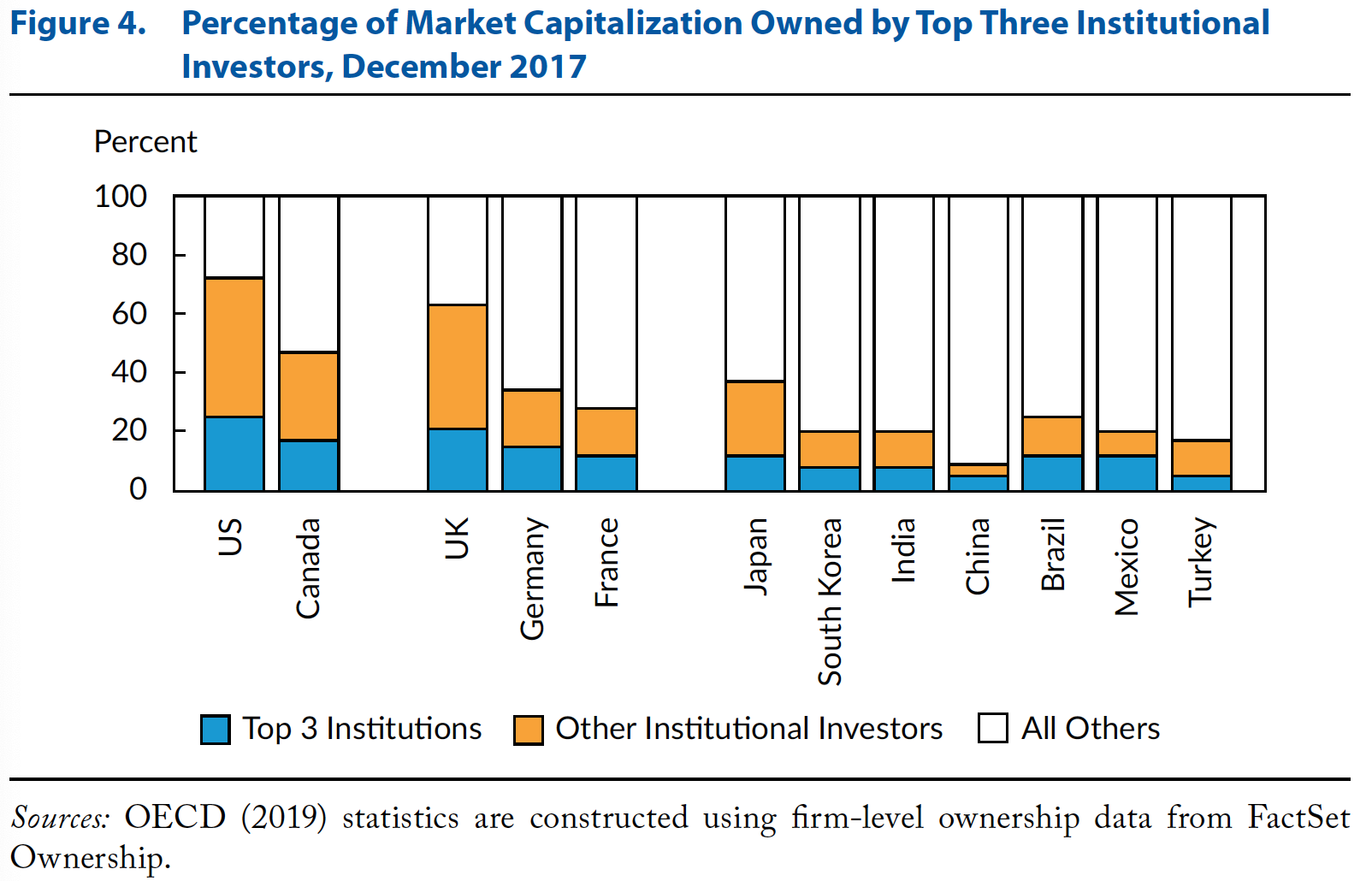

Figure 7.5: Large institutional investors own the majority of equities. This is where the power is, GME notwithstanding. Source: CFA Institute (2020)

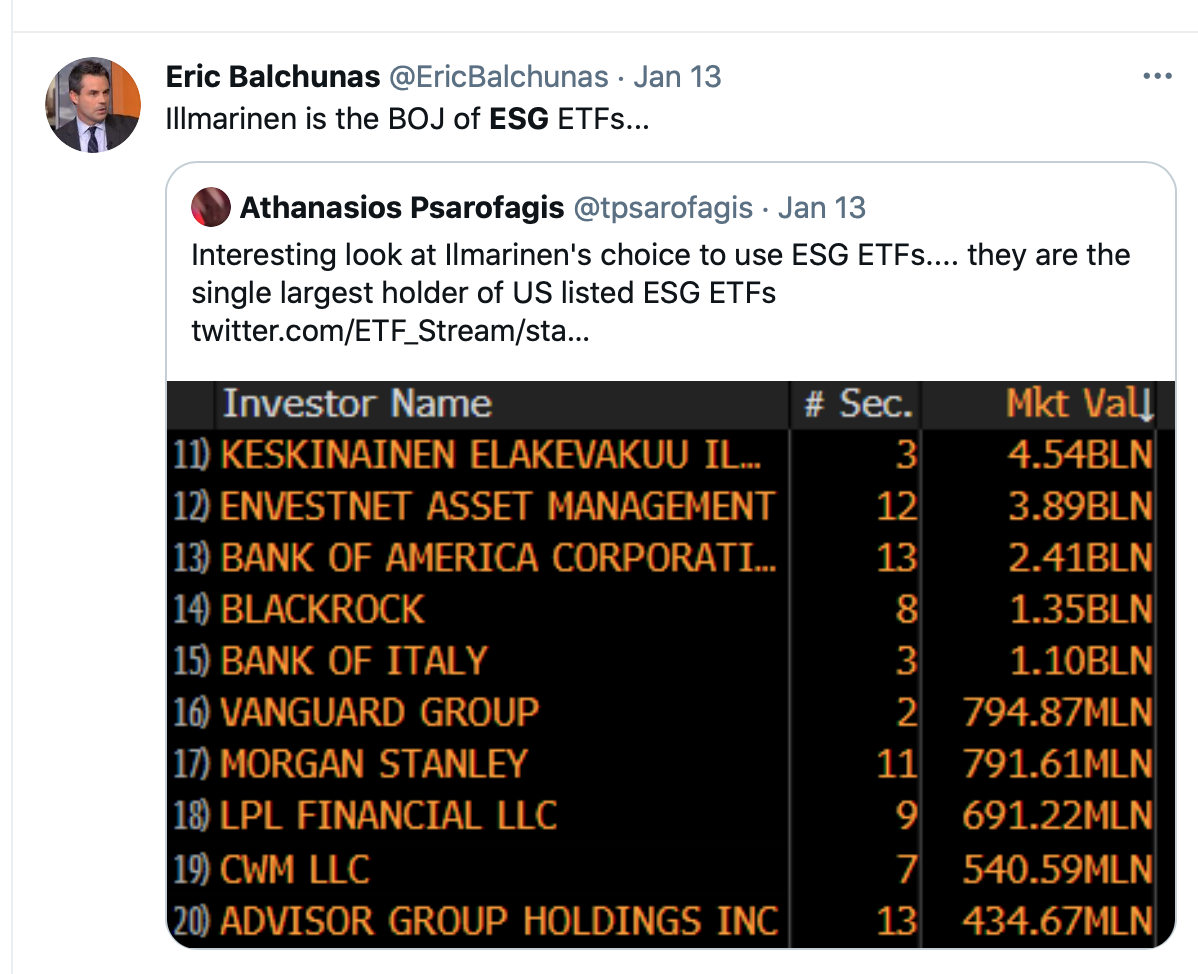

The Finnish insurance companyIlmarinen owns numerous ESG ETFs in their portfolio and is, in fact, the largest global customer for these products.

Figure 7.6: Big in Europe. Source: Twitter

Some investors are trying to take direct action, rather than just divesting from certain types of stocks, like coal firms. In August 2019, CEOs of large U.S. firms signed the Business Roundtable’s Statement on the Purpose of a Corporation, which stated that shareholder maximization is not the only goal of the firm. Matt Levine of Bloomberg has something to say about this letter (8/26/19):

Last week the Business Roundtable, an organization of chief executive officers of big U.S. companies, announced that it had changed its views on “the purpose of a corporation.” The purpose, it said, is no longer just to serve shareholder value; now corporations are supposed to serve customers, employees, society and other stakeholders. It sounded like the Business Roundtable was endorsing stakeholder capitalism. Was it?

No, of course not, I said immediately. Obviously the CEOs of the biggest U.S. companies were endorsing director primacy, but by another name. They were saying that they, the CEOs, should have more leeway to prioritize other issues besides shareholder value. “The managers and the board,” I wrote, “are the only ones representing all of the constituencies, so they are the only ones qualified to evaluate their own performance.”

7.1.1 Voice or Exit?

The book Exit, Voice, and Loyalty is a classic text in sociology that makes its way into a lot of different areas of finance and economics. To summarize, if you are part of an organization and you don’t like what is going on, do you speak up or “vote with your feet?”

Think about this from the asset manager’s standpoint. Do you sell a stock (or never buy it) if you disagree with management? Or, do you try to change the firm? You can see how this would come up all of the time in ESG investing. From the FT (1/26/21):

When more than 600 institutional investors gathered for a Bank of America conference in December to talk about environmental, social and governance (ESG) themes, one topic rarely discussed among Wall Street elites was very much part of the conversation: divestment.

Seen historically as a pressure tactic reserved for students and religious investors, divestment has become an issue that the world’s biggest asset managers can no longer ignore.

BlackRock, the world’s largest asset manager, announced a year ago that it would eliminate from its active investment portfolios any companies that generate a quarter of their revenues from thermal coal production. At about the same time, BNP Paribas asset management said it would exclude companies that derive 10 per cent of their revenues from coal production. The company said it would also exclude high-carbon-emitting power companies.

But divestment comes at a cost. Investors might lose out on juicy returns in legal and profitable — albeit controversial — companies. They also lose their voice as partial owners of a company when they sell their stakes.

Whether investors should divest or engage — or execute a combined strategy — was a key question for the Bank of America gathering and has rippled throughout the financial industry.

“We expect this will be a hotly debated issue in 2021,” says State Street Global Advisers, which has $3.2tn of assets under management, in an ESG outlook report for the new year.

7.1.2 Current Landscape

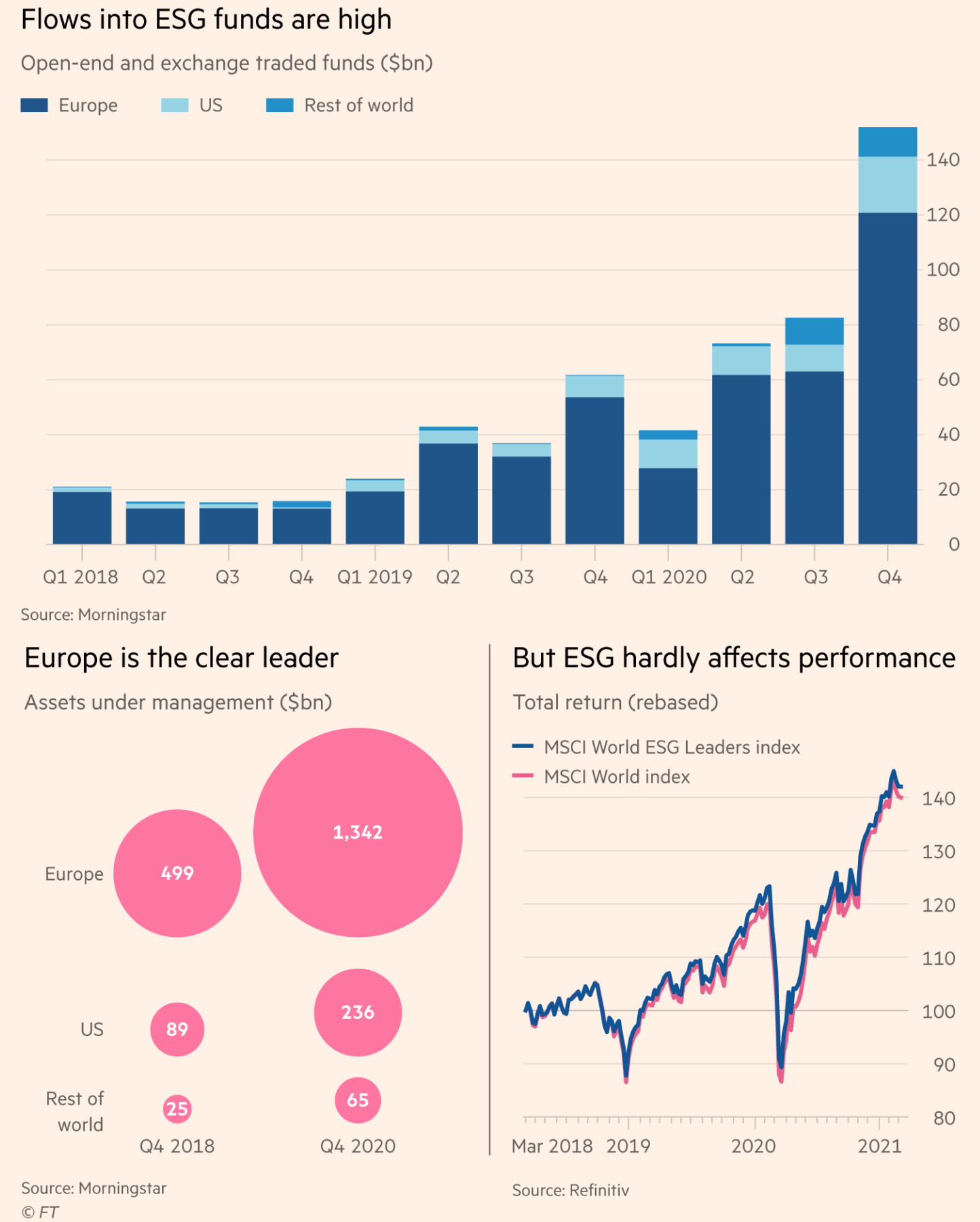

ESG is growing, even as investors are still trying to sort out exactly what ESG means. Figure 7.7 shows this growth. Does it matter that ESG performance, at least in raw terms, is basically the same as non-ESG performance?

Figure 7.7: ESG and, particularily, ESG in Europe, has seen a lot of growth. Source: FT

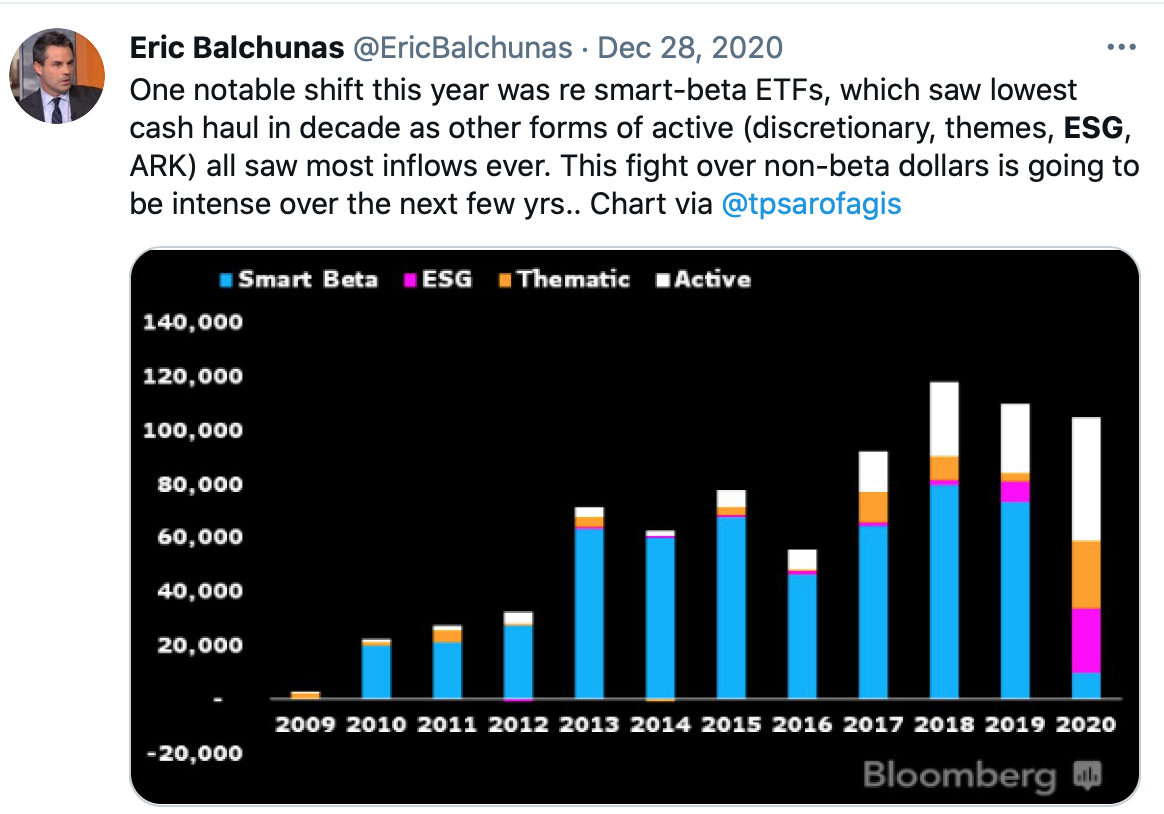

Figure 7.8: 2020 has seen more ESG and thematic investing, and less “smart beta.” Source: Twitter

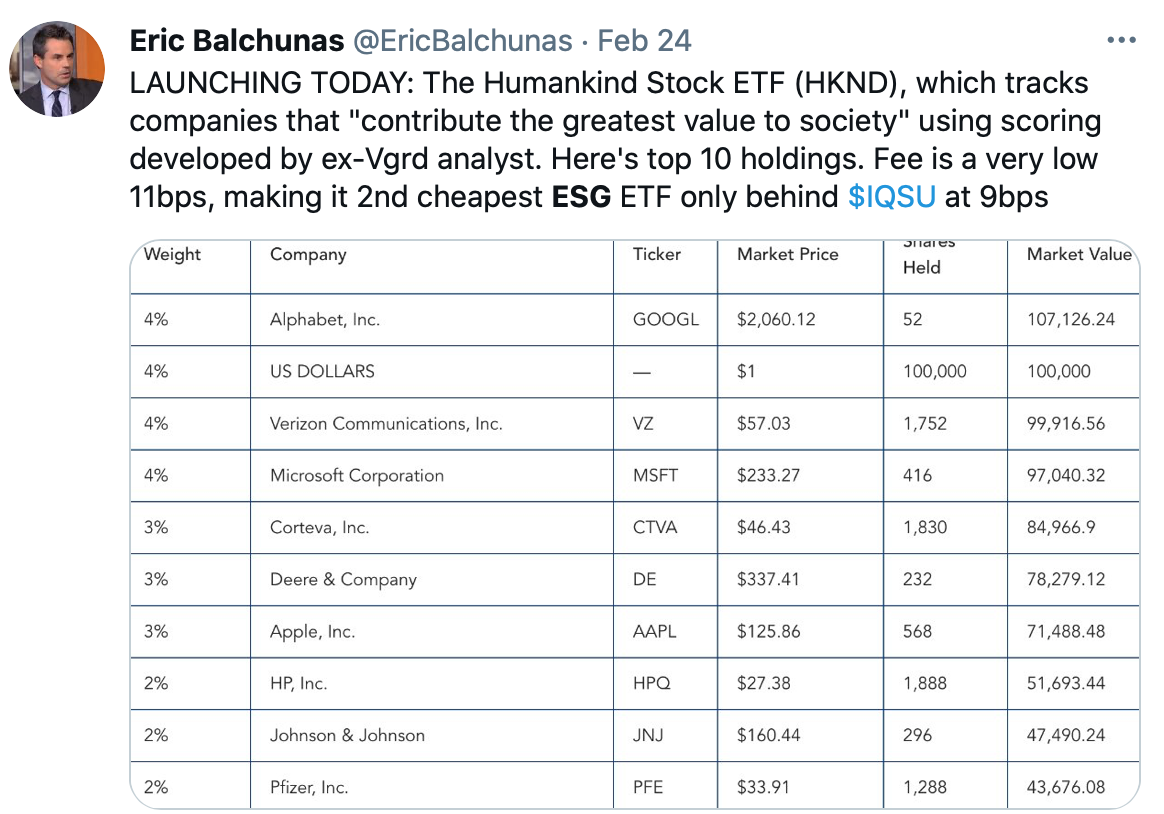

Retail investors are also getting new choices at lower costs, as ETF products proliferate.

Figure 7.9: ESG investing (or socially responsible investing, more specifically) was one of the first kinds of “thematic investing,” at least to me. Source: Twitter

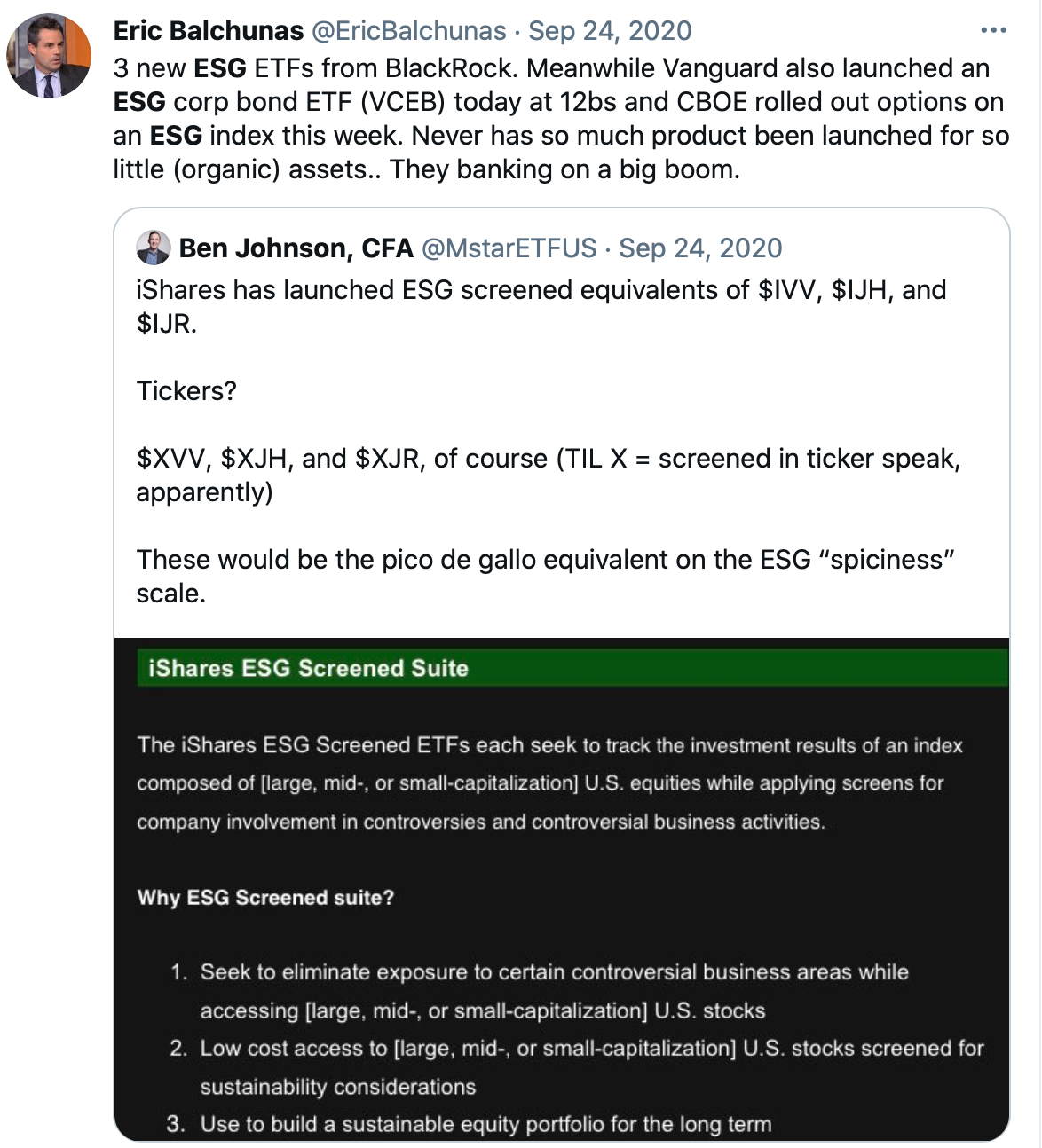

Figure 7.10: So many new products… Source: Twitter

It can be a bit difficult to decide what an ESG investment looks like. For example, are clean energy ETFs ESG? Seems like it to me, but others disagree. They sometimes get put into a different category.

Figure 7.11: How can we define an ESG fund? Source: Twitter

Finally, AQR is one of the few hedge funds that has ESG products. Because they are large, systematic, and focused on institutional accounts, it is in their interest to do so.

7.2 Where Do We Stand?

This is a rapidly growing and changing area of finance, as we’ve seen above. What do we know about ESG investing, though? How has it performed? What has its impact been, if any? And, can we make it better?

7.2.1 ESG Performance

There are two questions here. Do ESG stocks have different risk-return characteristics from other stocks? And, do ESG-focused funds have different risk and return characteristics than other funds. There’s a large literature on this.

In theory, “bad” ESG stocks should have higher returns if investors prefer “good” ESG stocks, all other things equal. The idea is simple: If your stock has a bad characteristics, then investors will “demand” a higher return for owning it, just like with any other risk. Framed differently, the “bad” ESG firms have a higher cost of capital.

Is this born out in the data? There evidence across global markets that firms with higher ESG scores are lower risk, but that they don’t have any better risk-adjusted returns. This makes sense from a theoretical perspective. However, there is evidence that you can trade the change in ESG, as firms move from a low-ESG state to a high-ESG state, if you can predict this.

Work from Pedersen and others at AQR proposes a model with three types of investors: those that are not aware of ESG, those that are aware of it and use it to price stocks, and those that prefer it. They do this to show the trade-offs in Sharpe Ratios between choosing a portfolios that use ESG information vs. portfolios that prefer high ESG scores.

Joliet and Titova (2018) study how U.S. equity SRI funds make their investment decisions. They find that they consider the usual suspects of fundamental factors, such as earnings growth and past returns, but that they do weight stocks according to relative ESG performance. The the choice to hold a stock, however, is based more on economic fundamentals than ESG.

We can also look at ESG through a factor lens, like everything else. Andrew Ang at Blackrock writes:

Investment factors—like value, momentum, quality, size, and minimum volatility—satisfy four criteria: 1) Each factor has a solid academic rationale for the existence of a return premium. 2) There are decades of empirical evidence that support the premium. 3) Their return patterns are value-added to market cap indexes and they exhibit low correlations with other factors. 4) They can be implemented at scale.

Some, but not all ESG characteristics fit these four criteria. So, ESG by itself is not an investment style factor that is broad and persistently rewarded. But those ESG data that do meet these criteria can be incorporated in signals alongside more traditional financial data to create portfolios that seek to capture the factor premiums but that are also more ESG friendly.

You can read a summary of ESG exposure via a factor lens here. What types of firms do you think have high ESG scores? What sort of factors do you think “make up” the returns of these stocks?

Moss et al. (2020) find that Robinhood investors do not care about ESG events. I am… not surprised. However, the evidence is that other retail investors do care about ESG and will change their portfolios in response to something like an oil spill.

7.2.2 ESG Data Issues

Like with credit ratings, there are numerous firms that give companies ESG-based ratings. In short, there’s little agreement across rating agencies. Billio et al. (2020) find that rating firms can have opposite opinions and that it is difficult to figure out if an asset manager is actually following ESG practices, since everything will depend on the benchmark you choose. Because there is so much disagreement about what ESG means, it is difficult to find much of an affect on performance, as mentioned above.

Other researchers have found similar issues.

![Different agencies, different ESG ratings. Source: Berg et al. (2019)[papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3438533]](images/06-esg-disagreement.png)

Figure 7.12: Different agencies, different ESG ratings. Source: Berg et al. (2019)[papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3438533]

How can we address these issues? This is hard work! From the FT (3/10/21):

ESG standards coalesce as EU launches new era of greenwashing prevention. Beginning today, investment managers in Europe claiming to be green must also include new, black-and-white disclosures.

The Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR), which comes into effect today, requires financial companies and big investors to disclose the risk they face from environmental, social and governance (ESG) issues — such as climate change and human rights — as well as how their investments impact these same issues (a concept known as “double materiality”).

This regulation is a big part of the EU’s plan to promote responsible investing, and is likely to have a ripple effect that extends far beyond the continent. But there is still one big problem that needs to be solved.

To make these disclosures, asset managers need data from companies — and as long as there is an “alphabet soup” of different ESG standard setters, companies will not have a clear picture of what they should report or how they should report it.

7.2.3 Does ESG Change Firm Behavior?

A few large investors, like Vanguard and Blackrock, own a large percentage of, essentially, every firm. There is growing research that this might matter is some areas, as firms with common co-owners have less of an incentive to compete with each other. How might this affect ESG investing?

What if these investment managers got together and told all of the firmst that they own that they need to do certain things? This might be happening. From the FT (3/10/21):

As Europe unveils new rules to combat greenwashing, 35 big investors have come together to establish what it means for asset managers to make net-zero carbon emission pledges.

This morning, the group of investors, which includes BlackRock, Aberdeen Standard Investments, Pimco and others, debuted a blueprint to decarbonise portfolios in a way that is consistent with 1.5C net-zero emissions.

The plan calls for portfolio construction to favour investing in climate solutions, tougher engagement with companies about their carbon emissions and selective divestment. The engagement component includes publishing voting records and a rationale for deviating from a policy. For corporate bonds, investors should secure agreements with companies so that sustainability-link debt criteria are met during the lifetime of the bond.

While the framework creates its own reporting standard, investors using the guidelines are encouraged to disclose their targets, and report annually on progress towards these targets.

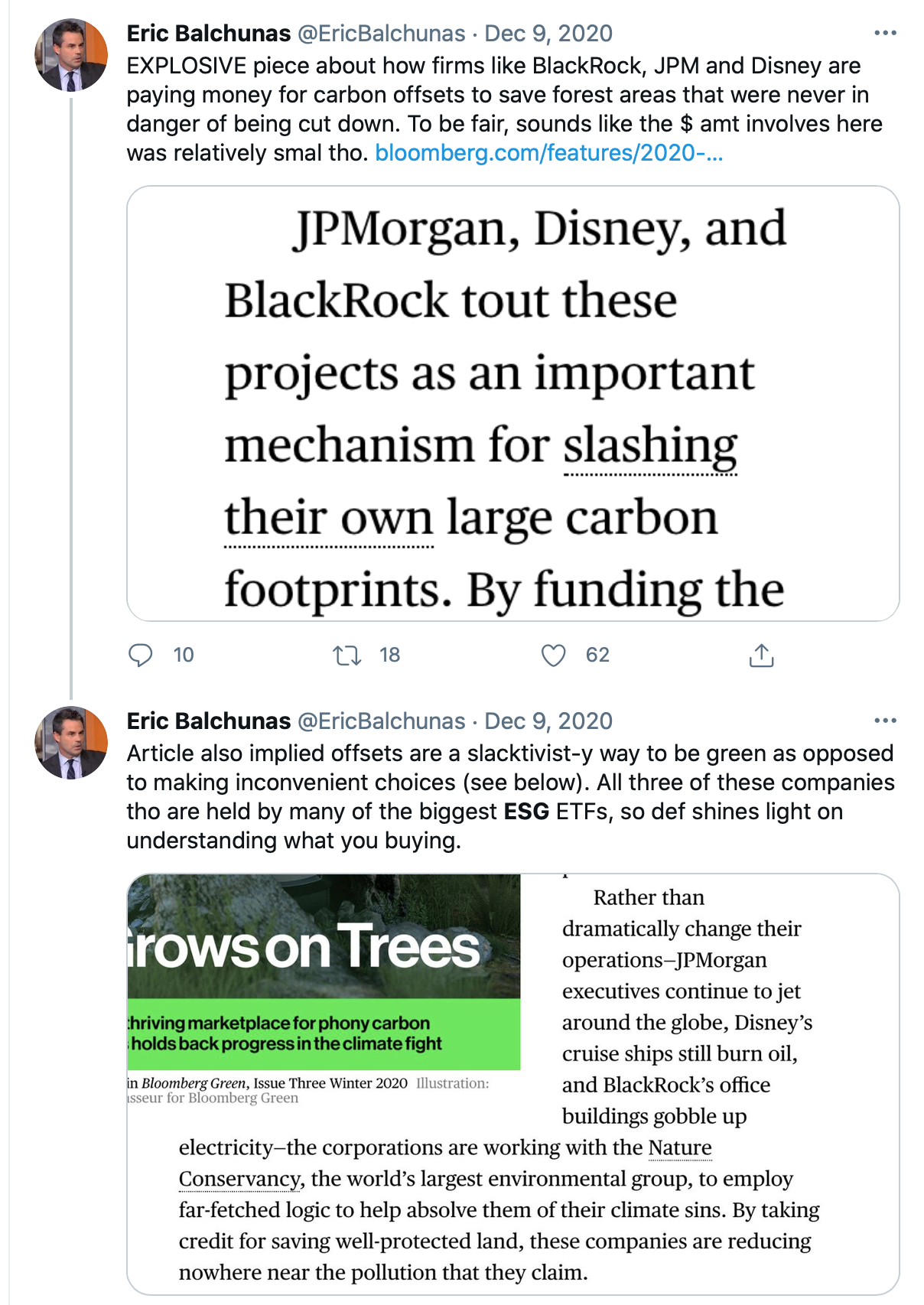

If you start to invest in the ESG world, you will hear the term greenwashing. This essentially means saying that you’re “green,” making sending out some press releases and making some visible donations, but then not doing the hard work. Or, even worse, actively working against your stated goals.

Figure 7.13: ESG investing can be about keeping firms honest. Source: Twitter

I mentioned the Business Roundtable Letter above. Raghunandan and Rajgopal (2020) find that the firms that signed this letter stating that they believed in stakeholder capitalism commit more labor and environmental compliance violations, have greater market shares within their industry, spend more on corporate lobbying, and have lower alphas and worse operating margins. There is also little correlation between signing the letter and ESG data. Their conclusion - talk is cheap.

One of my favorite ESG papers looks at an example that is not greenwashing. The authors look at how firms respond when targeted by climate-focused activist investors. Using plant-level pollution data, they find that environmental activists cause a reduction in greenhouse emissions and cancer-causing pollution. With so much greenwashing going on, it is interesting to see what happens when investors try and succeed to directly impose their beliefs on firms via voice.

Koijen et al. (2020) take on the big picture and ask what types of investors matter for expected returns. In other words, do certain investors, such as hedge funds or households, matter more when pricing stocks. Estimating the demand curve for any product or asset is non-trivial. They find that hedge funds and small active investment advisors are the most important price setters in equity markets. However, non-U.S. investors are the most important ESG pricers. This makes sense if European investors are more likely to consider ESG characteristics when making their investment decisions.

Noh and Ohn (2020) follow on the Koijen et al. (2020) paper and find that institutional investors with generally green portfolios do not cause green improvements at firms. However, investors who are willing to hold high environmental score firms, regardless of price, cause the firm to adopt more environmentally friendly policies. This seems to suggest, like the activism paper above, that voice is an important part of ESG investing.

Krueger et al. (2018) survey investment managers and find that long-term, ESG focused investors consider engagement (voice) to be more important than divestment (exit). Dyck et al. (2017) find that institutional investors from countries that place more importance on ESG issues “import” their beliefs to the firms that they invest in.

What does all of this mean? Large institutional investors can affect firm behavior, if they want to. What about individual investors? I think that this where there might be opportunities? Could individuals coordinate, like they have on Reddit with GME, and actually do something socially useful and vote their shares in accordance with their beliefs? Can we use our voice and maximize our welfare?

7.3 A Comment on Bubbles

Returns come from risk. Sometimes, it can seem like returns get ahead of themselves as investors become enamored with whatever is shiny and new. And, sometimes, things become expensive because they are “good” – they are less risky, they have high expected cash flows, and people want to own them.

Not everything that is expensive is a bubble. Hedge fund managers engaging in macro-tourism (i.e. stock pickers who suddenly have a view on monetary policy) predicting higher Treasury yields ever since 2010 have found that out, even if rates head higher now. You can’t be wrong for a decade and then declare yourself right in investing. Doesn’t work that way.

I actually have a somewhat optimistic view of “bubbles,” or, at least some bubbles, from the standpoint of greater society. The type of bubble matters and financial excess can lead to lower future growth. However, history is full of technological changes that are hard to price and cause temporary market euphoria. As a society, we sometimes end up with a lot of important new technology, even if there’s short-term pain. Other times, of course, we get left with abandoned houses in the Arizona desert that quickly depreciate to zero.

I will leave you with this about ESG and possibility of an ESG/technology bubble from the FT (3/4/21):

Last month, Nicolai Tangen, the head of Norway’s $1.3tn sovereign wealth fund, said that investors had been right to back tech companies in the late 1990s — even if valuations went too high — just as they were right to back ESG stocks today. “What is happening in the green shift is extremely important and real,” Tangen said. “But to what extent stock prices reflect it correctly is another question.”

If the past is any guide to the future, we can hope that this proves to be a productive bubble, whatever short-term financial carnage may ensue.

In her book Technological Revolutions and Financial Capital, the economist Carlota Perez argues that financial excesses and productivity explosions are “interrelated and interdependent.” In fact, past market bubbles were often the mechanisms by which unproven technologies were funded and diffused — even if “brilliant successes and innovations” shared the stage with “great manias and outrageous swindles.”

In Perez’s reckoning, this cycle has occurred five times in the past 250 years: during the Industrial Revolution beginning in the 1770s, the steam and railway revolution in the 1820s, the electricity revolution in the 1870s, the oil, car and mass production revolution in the 1900s and the information technology revolution in the 1970s.

Each of these revolutions was accompanied by bursts of wild financial speculation and followed by a golden age of productivity increases: the Victorian boom in Britain, the Roaring Twenties in the US, les trente glorieuses in postwar France, for example.

One of the authors is a Nobel Prize winner and the author is an economist at the University of Chicago. I just point this out to make it clear that you can be an orthodox economist who loves markets and still think that maximizing the share price isn’t the only thing that matters. The world is complicated.↩︎

We’ll talk about data issues and the subjectivity of these measures below.↩︎