5 Asset Allocation and Factors

The core of asset allocation is really about the inputs into mean-variance investing. You can add a lot of bells and whistles to this framework, but you’ll keep coming back to your capital market assumptions, such as expected returns, the risk of each asset or factor, and how the assets or factors move together (covariance). You are looking for a diversified set of risk premiums to collect together in a portfolio.

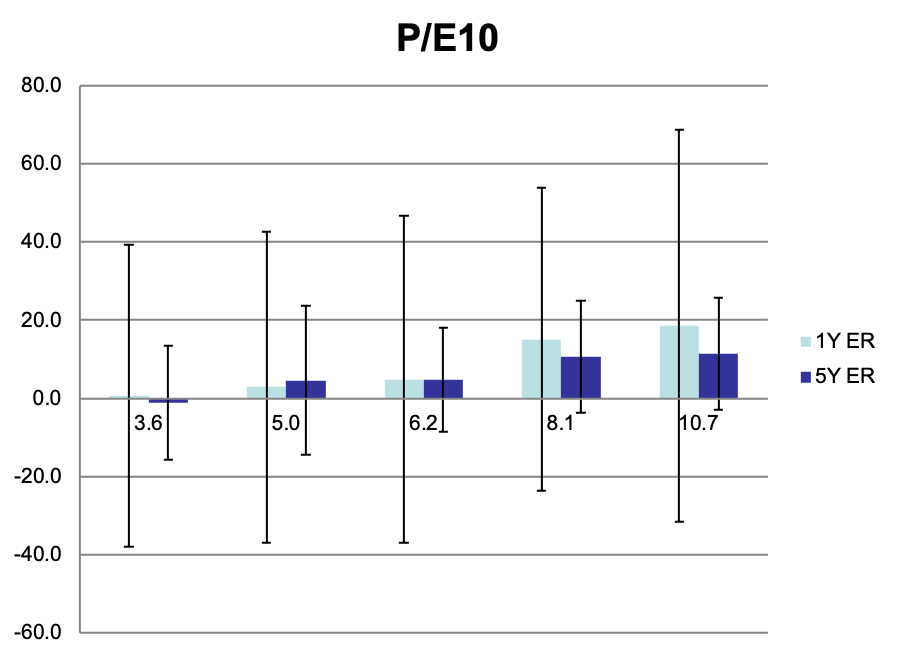

You’ve done this in FIN 412 when you found optimal portfolios along the efficient frontier. These are the portfolios that maximize expected return for a given level of risk. Or, equivalently. minimize risk for a given expected return. In this chapter, we’re going to focus on one particular aspect of this process: forecasting the equity risk premium, one of the most important returns that we need to consider. There are, of course, other returns, such as bond yields and other types of equities and factor premiums that you might be interested in. And you also need to estimate how assets and factors will move together. This last part often takes the form of a covariance matrix.

This chapter ends with some thoughts on how institutional investors might then delegate the investment decision. Let’s say that you’ve decided to have 35% of your endowment fund in U.S. equities, perhaps with a tilt towards value or small stocks. How might you select these managers? We discuss how MIT’s endowment goes about this process.

Our case study this week looks at the pension fund for Cook County, Illinois, their asset allocation decisions, and how these relate to their funding status.

Finally, some of this material makes its way into the Levels 2 and 3 CFA curriculum.

](images/04-triumph.jpg)

Figure 5.1: Equity investing is about risk tolerance and optimism. This book, which documents asset class returns across time and countries, came out in 2003 and we’ve seen the optimists triumph again after 2008 – 2009. Source: Princeton University Press

5.1 Importance of Asset Allocation

Let’s start by thinking about strategic asset allocation. Large institutional investors usually first decide on their long-run strategic choices, such as their allocation to U.S. stocks or bonds. Lately, these investors might also think more about their specific factor tilts, such as value vs. growth, but the big choices are still the big risk factors, such as the equity risk premium and deflation hedges, such as Treasuries. These choices gtive the fund their desired, typical portfolio consistent with the investment goals (around which one can implement tactical bets and security selection views). What are the steps?

- Set the strategic portfolio based on investment goals and long-term views.

- Vary asset allocation around strategic holdings based on tactical views on asset classes.

- Implement asset class positions based on security selection views.

Perhaps the most important consideration here is getting your asset-liability match correct. You’ll see this more in our case study. In short, when choosing your asset or factor allocation, you want to keep in mind why you are investing and when you’ll need the cash. You’ll want to be aware of something called sequence risk, or the risk of a big loss right when you need to spend down your investment.

How much does asset allocation matter? A lot, or a little, depending on how you ask the question. A very well-known paper in the asset allocator community attempts to ask these questions.

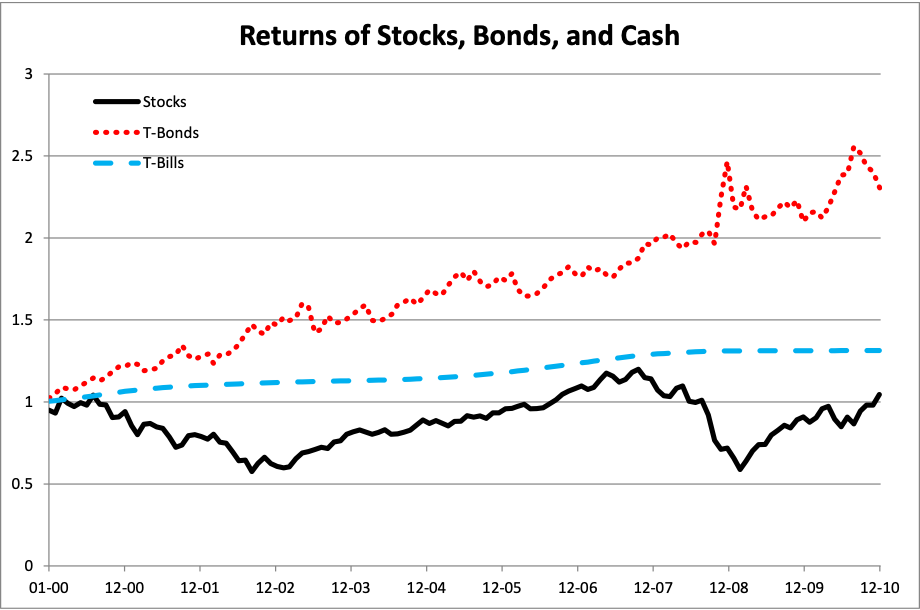

Let’s start with the first question: For a single fund, how much of the variability of returns across time is explained by policy (i.e. asset allocation to equities, bonds, etc.)? In other words, how much of a fund’s ups and downs does its policy benchmarks explain? To quote Ibbotson and Kaplan (2020), Figure 5.2:

illustrates the meaning of the time-series R2 with the use of a single fund from our sample. In this example, we regressed the 120 monthly returns of a particular mutual fund against the corresponding monthly returns of the fund’s estimated policy benchmark. Because most of the points cluster around the fitted regression line, the R2 is quite high. About 90 percent of the variability of the monthly returns of this fund can be explained by the variability of the fund’s policy benchmark.

The mutual fund in this example allocates to a variety of asset classes, such as stocks and bonds. Their returns over time are basically explained by this decision. The particular stocks and bonds that they bought don’t explain nearly as much.

](images/04-howmuch-fig1.png)

Figure 5.2: Source: Ibbotson and Kaplan (2020)

Note that this is a time series regression. It is asking does asset allocation explain a fund’s returns over time. The answer is - yes! The fact that a fund takes on equity risk, or small-stock risk, or value-stock risk, etc. explains their returns. We saw this when we ran regressions in class. The stocks you pick matter less than the fact that you pick stocks if I want to explain your returns over time, at least if you are a typical mutual fund or pension fund equity allocation. If you just pick one stock and that stock is GME, then this conclusion won’t hold.

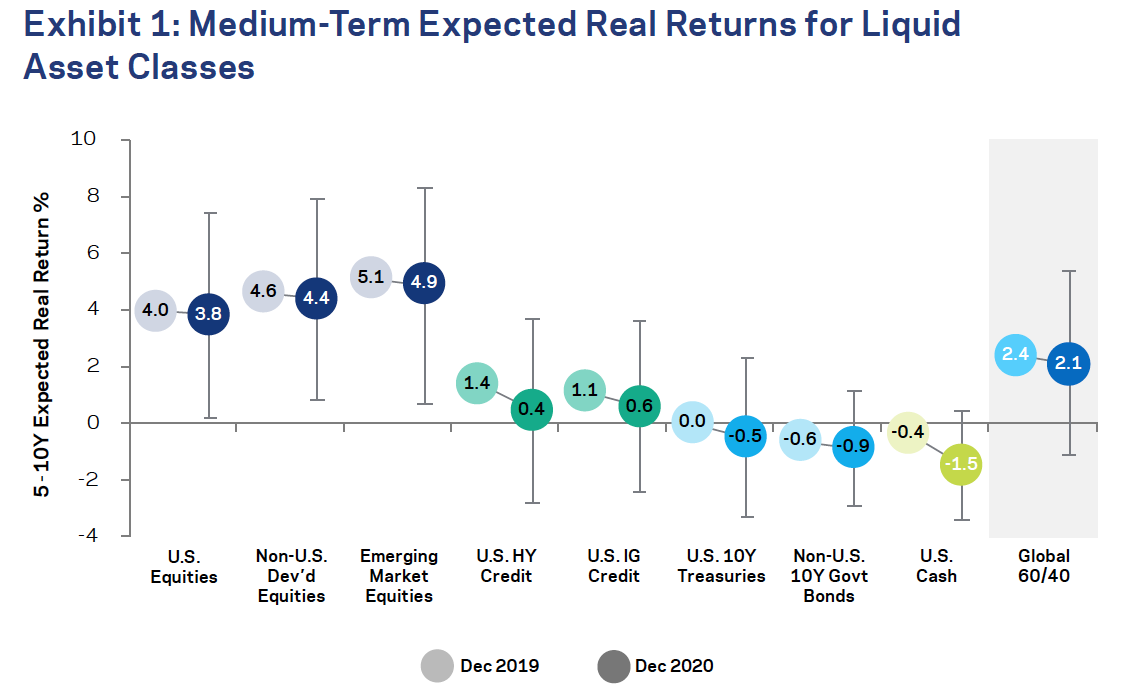

But, what about comparing you to other funds? How much of the variation in returns among funds is explained by differences in policy? In other words, how much of the difference between two funds’ performance is a result of their policy difference? Again, quoting Ibbotson and Kaplan (2020), Figure 5.3:

is the plot of the 10-year compound annual total returns against the 10-year compound annual policy returns for the mutual fund sample. This plot demonstrates visually the relationship between policy and total returns. The mutual fund result shows that, because policy explains only 40 percent of the variation of returns across funds, the remaining 60 percent is explained by other factors, such as asset-class timing, style within asset classes, security selection, and fees.

](images/04-howmuch-fig2.png)

Figure 5.3: Source: Ibbotson and Kaplan (2020)

Policy return is what you would earn if the fund had just invested in a passive index that matched their stated policy, or strategic asset allocation. In other words, if all funds had the same benchmark, but invested actively, then 100% of return differences would be explained by things like security selection, rather than their benchmark. However, if all funds were passively managed, but had different benchmarks (i.e. different amounts invested in equities and bonds), then 100% of the return differences between funds would be explained by policy differences, so no fund would be making active decisions, like security selection or market timing. When looking at this small sample of funds, the authors found that 40% of the return differences across funds could be explained by different asset allocations, while the rest of the differences were because some funds were deviating more from their benchmarks.

5.2 Factors, Assets, and Risk

How do sophisticated investors view their portfolios? The details are beyond the scope of our brief time together, but just note that there is software that helps you see into your portfolio and find your exposures. This means that you can know what risks are lurking, assuming that you have access to all of your positions. Of course, any single fund manager will have their entire book in detail. However, if you are an allocator, you might not have access to your underlying hedge fund positions – in fact, you almost certainly won’t. In that case, you might need to infer your exposures from fund returns (which you will observe) and/or your funds’ general underlying strategies.

Here is a Twitter thread discussing how a large market maker like Citadel uses factors to figure out what risks they have on their giant trading book, so that they can hedge the unwanted risks away. Citadel is going to use their own, proprietary software, but there is software that you can buy that does this sort of thing too. We’ve also already seen similar software from Two Sigma and Blackrock’s Aladdin.

You can see how Two Sigma forecasts factor returns from their own research. They are trying to come up with a simple (parsimonious) list of factors that explains most of the returns that you see in a typical institutional portfolio. They use the phrase orthogonal a lot, which is just a math term that can be loosely translated as unrelated. They comment that premiums, such as equity risk, can be found across asset classes, not just in equities themselves. Which leads us to our next topic.

5.4 Institutional Investors and Delegated Investing

Once in the dear dead days beyond recall, an out-of-town visitor was being shown the wonders of the New York financial district. When the party arrived at the Battery, one of his guides indicated some handsome ships riding at anchor. He said, “Look, those are the bankers’ and brokers’ yachts.” “Where are the customers’ yachts?” asked the naïve visitor. - Where are the Customers’ Yachts (1940)

We’ll end by talking about institutional investors themselves. These are the people making the asset allocation decisions and selecting the managers. They may or may not do some of their own security selection, but, typically, most of that is delegated. What incentives shape their decisions? What problems come up? How do they make decisions? And, perhaps, how should they make their selections?

The typical pension plan has 24% of their fund allocated, broadly, to alternatives, such as hedge funds. High-net worth individuals also use a lot of alternatives, though this could include private investments, such as real estate, as well as hedge funds.

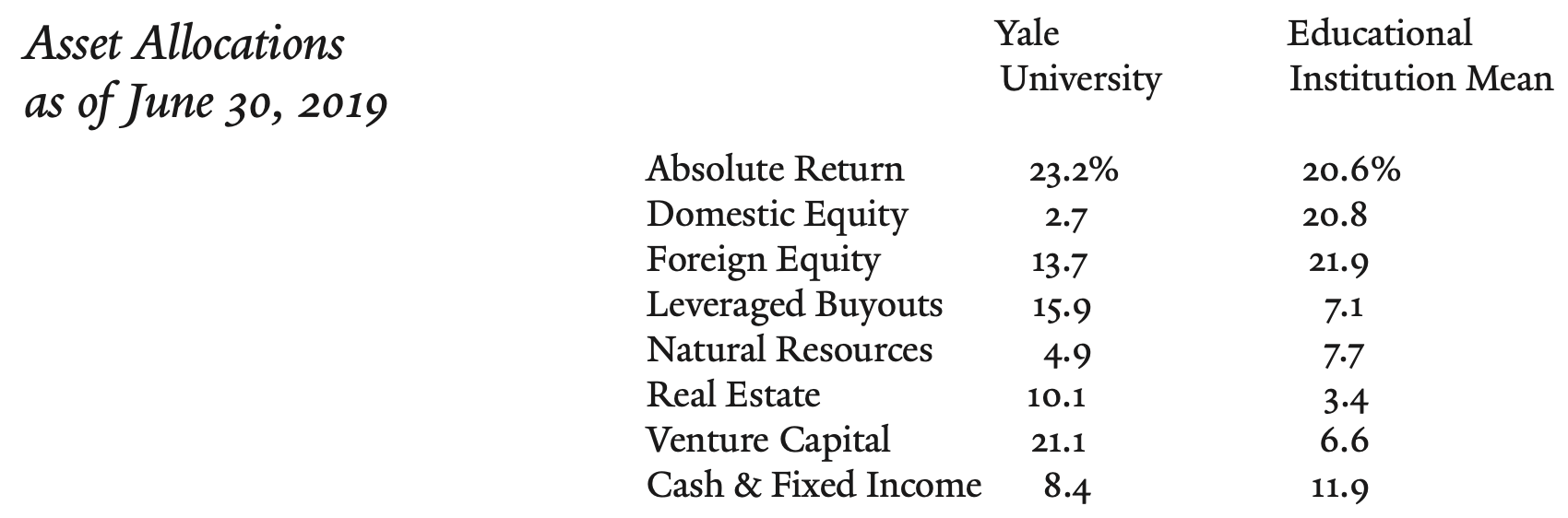

Figure 5.10: A lot of universities, such as Yale, investment in hedge funds, called Absolute Return here. Elon’s endowment also uses hedge funds. Source: 2019 Yale Endowment Report

When you delegate your investment decisions to outside managers, you create a principal-agent relationship, which can lead to principal-agent problems. The principal is the asset owner, like the University, who is allocating via their endowment board or office. The agents are the fund managers that they hire. To reduce conflicts that can arise between these parties, we should think a little bit about contracting and governance among allocators and fund managers. Much of this material comes from Ang (2014).

The two big problems are:

Adverse selection. The allocator can not directly observe the manager’s ability and might even have difficulty observing the actual strategy. This leads to both good and bad funds entering the market.

Moral hazard. The allocator is unlikely to be able to directly observe how hard the manager is working.

To mitigate these issues, the allocator and fund manager will negotiate a contract that aligns their interests, while being agreeable to both parties. This might mean outcome-based contracts, like performance fees, behavior-based contracts that restrict the types of investment that the manager can do, and non-linear, option-like contracts that payoff for the manager when they perform particularly well. You’ve seen these types of contracts already when we discussed hedge funds.

The investment world is also what economists call a repeated game, so reputation is very important. Due diligence visits and phone calls with existing investors are each part of the usual investment process.

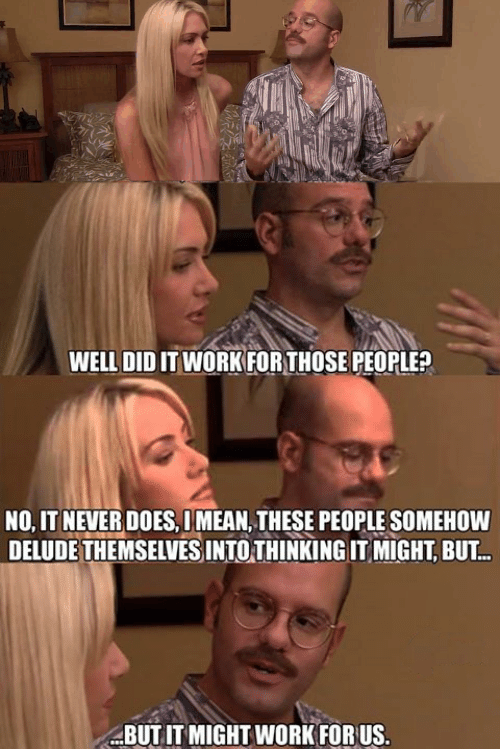

5.4.1 Know Your Limitations (and Your Opportunities)

What would I do if I were an institutional investor, allocating capital to meet my organization’s goals? My default would always be to prefer the cheap alternative. Some managers have skill, but it might take a decade or more of returns to show this statistically. By then, it would be too late as flows chase performance and whatever edge the manager had disappears. Markets also change, so an edge in one market cycle might not matter as much in another. To catch a manager earlier, you have to rely on understanding their process, whether or not they can actually do what they say they can, and other difficult to assess factors. It is easy to fool yourself into thinking that you or another manager that you’ve met with has an sustainable edge.

So, I would use cheap, easy-to-understand risk exposures for the bulk of my assets. Some factor exposures might be difficult to get in public markets, so we can keep an open mind here and see what the world of private equity and venture capital might offer in Chapter 6. But, in the end, I would likely spend most of my day doing absolutely nothing.

But, what if you wanted to do more? And, what if your institutional capabilities suggested that you could? What might those capabilities be? Here are a few characteristics of institutional investors that might want to try to do more than the basics:

Stable capital. Few clients and, in fact, maybe only one client. Little to no outside interference (e.g. from political entities, like a state legislature). No real possibility of a run on your capital. These helps in two-sided markets, as the funds that you invest in know that your hand won’t be forced. This description fits many larger university endowments and family offices.

Network of outside funds. Essentially, you need to know people. There’s no real way to find talented managers who are just starting without having that network in place. Venture capital and private equity work like this too. It’s why I’m suspicious of some of the newer vehicles that advertise more complex strategies for “everyday” people. Why weren’t they able to raise capital from the usual pool of sophisticated investors? Why do they need my money?

Knowledge of strategies. Why do certain strategies make money? When will they make money?

You can always use larger, more institutionally friendly hedge funds and private equity firms to get you factor exposures that you think might be difficult to come by using more passive alternatives, if you think that these exposures outweigh the fees. With this mindset, you aren’t focused on alpha, but are instead trying to put together a portfolio of risk premiums.

Figure 5.11: Picking hedge fund managers who have thrived using a niche strategy, but after they have grown their AUM.

You can also, of course, chase returns and allocate to funds and strategies that have a track record of strong performance, with the hope that this alpha continues into the future. I think that the evidence says that this is tough to do, but you can try. Best of luck!

The hard path is to look for small funds. Funds with managers who are not well known, who might have been overlooked. These are, somewhat optimistically, sometimes called emerging managers. These are managers without a long track record, or perhaps just a track record of trading their own money. Some larger university endowments will attempt to find these managers using their alumni network and stable capital base. For example, here’s an interview from 2014 with the investment team at MIT’s Endowment on how they select managers.

When evaluating managers, the MIT team focuses on judgment and process, the risks the manager takes (e.g. the factors they are exposed to), and the alignment of incentives.

We focus on evaluating opportunities that are within our circle of competence, which is bounded by our core investment principles. The nature of our research really boils down to: developing conviction in the quality of an investor’s judgment; understanding the risks to which our capital is exposed; and ensuring that the right structure and alignments exist to serve as the foundation for a long-term partnership. On a practical level, we spend our time conducting in-person meetings; reading any relevant materials, such as letters, investment case studies, or company materials; conducting reference calls; and analyzing historical data.

Again, you need to focus on the process of the manager. This is difficult if you don’t really understand the strategy and why it makes money (and when it doesn’t). For example, if you are looking for a long volatility fund to hedge risk in your portfolio, you need to think carefully about how these funds make money, how they structure their trades, and should understand option “greeks” basics to at least get a handle on their strategy.

Over time, we have learned that great investors tend to be more focused on process than on outcomes. So, we try to follow this principle as well. The idea goes that if the process is correct, results will take care of themselves over the long term. Of course, a track record, if presented over a long period of time, is an important check on whether what should work is working. But we have to be cautious about this, as even great managers have multi-year periods of meaningful underperformance – there is a great Eugene Shahan article from 1985 about how plenty of investors with great long-term track records looked mediocre in any given year and underperformed for three or more years in a row in many cases.

Finally, they meet with very young managers who have smaller AUM. If you want to catch a manager before they become successful, then you need to look at unconventional strategies and funds.

One thing that many people remark on when they meet us the first time is that we are very different from their conception of what a traditional institutional investor would be. They are surprised to hear we spend a lot of time meeting with managers in their 20s and 30s, that we are frequently the first or only institutional investor in a firm, that a meaningful number of our firms are one- and two-person shops, and that we are very content with unconventional firms and strategies. We have made a deliberate effort to invest in un-institutional firms because many investors with exceptional long-term track records have been unconventional and un-institutional.

MIT has an emerging manager program where they select funds with short track records and small AUM. One of their directors has a brief article on the types of funds they have selected with this program.

I try to use the factor thinking we’ve discussed to place managers and strategies into some kind of bucket. Sure, there are managers that might not fit a particular definition, but most get their returns from some kind of risk premiums.