Chapter 8 Module 5: Current Issues on Development

This Module includes topics that show some of the contemporary challenges and opportunities that low-income countries face.

Topics covered:

- Gender and Development

- Religion, Culture and Development

- The Curse of Natural Resources

- Environmental Degradation and Development

- The rural-urban divide and migration

8.1 Gender and Development

Another salient aspect of our identity that is deeply connected with development is our gender. Using a gender perspective helps us understand how resources are allocated based on our sex or gender.

Traditionally, a dichotomous version of this term has been used. Although this perspective is restrictive and limits our understanding, there are different reasons for this. First, most of the household data collected only uses a dichotomous question when asking about gender. Since economics largely relies on this surveys, this limits the type of questions we can answer. In part, this has to do with different legal restrictions and understandings of what gender is. Second, historically, biological sex is the most salient characteristic that defines how resources are allocated, regardless of a person’s gender.

As the readings for this topic show, gender inequality is still pervasive, with women (regardless their sexual preferences) facing the most challenging situations. This is pervasive in most of the areas in their lives. As Evans (2016) show, although women have accessed the labor market in most countries, they are still largely in charge of most domestic endeavors. This situation became evident during the Covid-19 pandemic where food insecurity in low-income countries increased, largely affecting girls and women.

The pandemic also increased the gaps in education between girls and boys. Although this difference is nothing new, it became more acute during the pandemic as boys returned to class earlier while many girls did not return to school at all. As Kwauk et al. (2021) show, one of the driving mechanisms behind that is teenage pregnancy and economic hardship. Furthermore, girls had less access to remote learning tools than boys (Population Council, 2021).

Girls and women are also more exposed to sexual and other types of domestic violence. Vaeza (2020) and Tesemma (2020) show how the pandemic exacerbated this violence, by bringing the victims and perpetrators together and changing power structures.

These inequalities go beyond household decisions on how to allocate their resources. In many ways, these inequalities are also structural. For instance, land in many African countries is distributed according to traditional practices. Yet, these practices prevent women from accessing land. One of the persons I interviewed during my fieldwork in Côte d’Ivoire explained to me that “land is power, and thus land access must remain restricted to men.”

Yet, this is not to say that sex is the only valid or important characteristic that should be analyzed. It is well known that the LGBTQ+ community is largely underrepresented and under-served. As the book Queer in Africa argues, “people with non-heterosexual sexualities and gender variant identities are often involved in struggles for survival, self-definition, and erotic rights”.

8.2 Religion, Culture and Development

What role does culture play in development? Until very recently, this question did not receive much attention. However, culture seems to be an exciting factor to analyze when examining development patterns. For one, culture seems to be rather persistent, but it is not immutable (Giuliano, P. and Nunn, N., 2018), so it may be the case that, as Guiliano and Nunn (2018) argue, culture mutates in less stable environments. This, in turn, implies that culture is not immutable. Therefore, contrary to common perceptions, culture seems to respond to the context, and it is not a systematic factor.

This idea goes in line with Spolaore and Wacziarg, 2013, who argue that even if long-term history matters, there is much variation, such as the diffusion of knowledge, which happens vertically –across generations– but also horizontally –across populations–. So, even if some believe that certain traits can be more “development prone,” it is important to acknowledge that cultures adapt and are “persistent but dynamic.”

Lopez-Claros and Perotti (2014) go a step forward and argue that culture can adapt and integrate a set of values that are universally desirable and compatible with the development of humanity, without imposing objectives that are relevant only in certain regions of the world.

Ethnicity and Development

Similarly to culture, ethnicity is a controversial issue. It is a fluid concept, but it carries tremendous political, social, and economic implications that cannot be disregarded (Englebert et al., 2018). It comprehends more than trait characteristics or language. It also contains values and aspirations that were reshaped and reinterpreted during the colonial period (Derg, 2020). This complicated the formation of nations after independence and has been a factor limiting development, as it has led to the configuration of neo-patrimonial state (Cheeseman and Fisher, 2019).

8.3 The Curse of Natural Resources

The role that natural resources play in promoting economic development is highly contested. Ross’s seminal research has focused on answering this question, showing that countries with abundant resources show lower levels of prosperity than countries with less abundant resources.

Yet, the mechanisms behind this are not so evident. After all, the final resource may depend on the type of natural resource exploited (see, for instance research by Ross (1999), Sanchez de la Sierra (2021), and others), the way it is exploited and the role of the state to manage it (see, for this, research by Saylor (2014)).

Evidence, has shown that the presence of natural resources by itself should not have a clear effect, irrespective of the type of natural resource. What matters is the type of institutions exist to manage those resources.

8.4 Environmental Degradation and Development

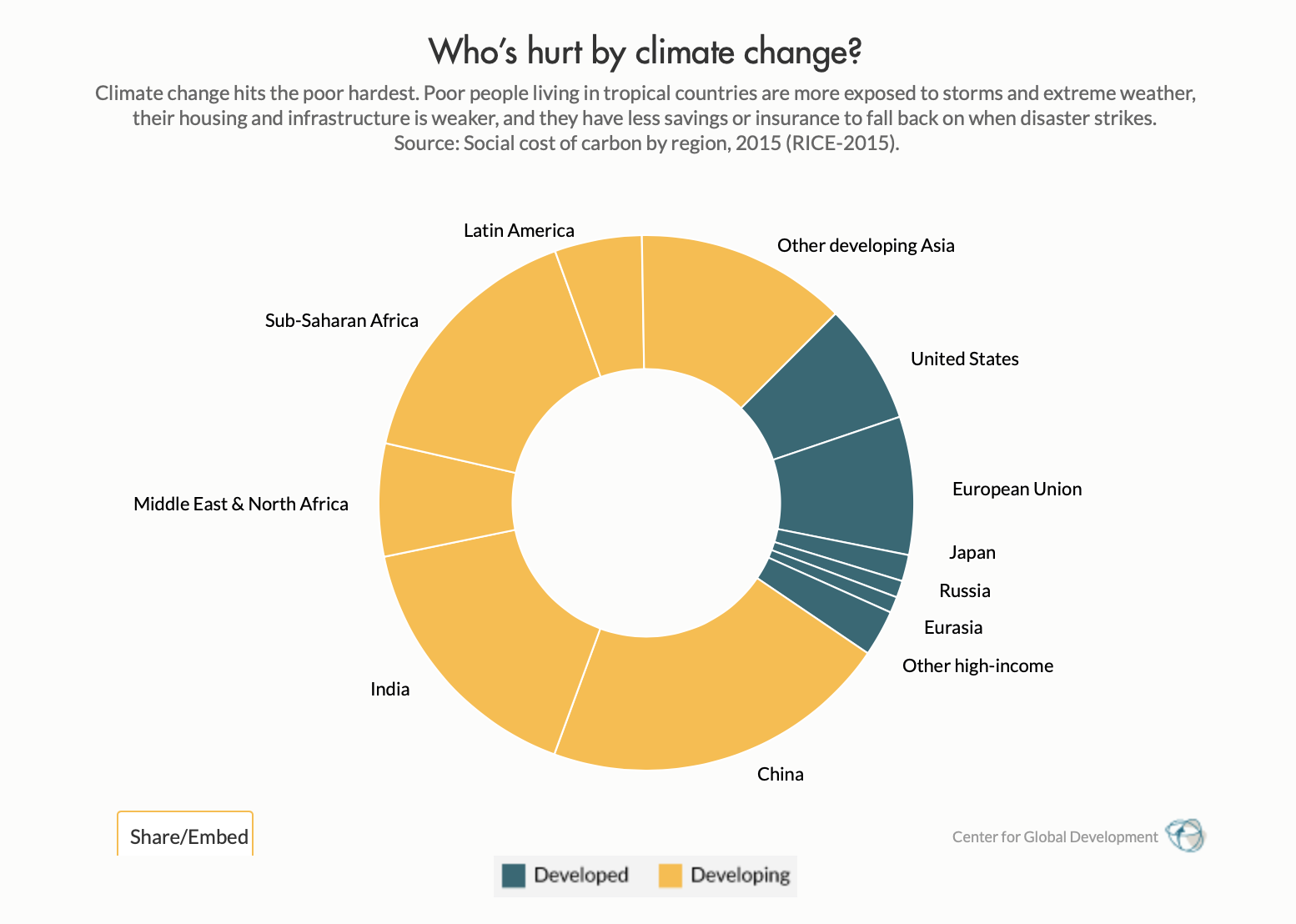

Climate change influences, and it is affected by migration, agricultural and industrial practices, institutional capacity, trade, and urbanization. Climate change and development are closely linked. People in low-income countries are the most vulnerable and the least resilient to face the challenges of environmental degradation.

People living close to the Equator are more exposed to extreme weather. Low-income countries (located, for the most part, in areas closer to the Equator) have less resilient infrastructure and they do not have access to insurance or other financial mechanisms to face natural disasters (remember the chart we saw in the last Module on the Ivory Coast?). They also rely more on agriculture and droughts or extreme weather could damage the crops, leaving households without access to a source of income. These countries also have less capacity to adapt, to more resistant crops, to a more sustainable manufacturing sector, and to practices that provide more resilience without compromising the population’s livelihoods.

Figure 8.1: Who is hurt by climate change? Source: CGD (2015)

One of the primary sources of degradation in many parts of low- and middle-income countries is deforestation17. In 2011, this practice was responsible for 1/5 of the emissions in Latin America, almost 1/3 in Sub-Saharan Africa, and 2/5 in Southeast Asia (CDG, 2015).

What consequences could climate change cause? Olmer (2018) studies the economic effects of climate change in India. He finds that increases in temperature are associated with a decrease in agricultural production and average wages. He also finds that there is a shift of labor from agricultural to the manufacturing sector.

In addition to the economic mechanisms linked to climate change, these are hardly the only ones. Climate change also affects social and political behavior. In a lab experiment, Miguel (2019) finds that higher temperatures incite anti-social behavior. Burke et al. (2009) predict that an increase in average temperatures in Sub-Saharan Africa will lead to an increase in civil conflict by about 5.9%. This is in large part because, as a large share of the population in the continent depend on agriculture, a variation in the temperature could have serious economic consequences for these households. This, in turn, may lead to an increase in ethnic or other type of conflict.

But, is environmental degradation avoidable? Malthusians and Neo-Malthusians argue that the current levels of consumption is unsustainable and that food and non-renewable resources will not keep track with expanding consumption, leading to scarcity, conflict, and rapid social, economic, and environmental degradation.

Still, according to Gleditsch (2021) environmental optimist, think that technological progress, market mechanisms, and national and international cooperation will prevent us from reaching the stage that NeoMalthusians predict. This optimism is sustained by evidence from previous crucial moments in history when some predicted a dire situation. The first of this moment occurring right before the Industrial Revolution, when Malthus argued that, since the population was increasing at an exponential rate, whereas food production was only growing at an arithmetic rate, ‘preventive checks’ were necessary to avoid human conflict. NeoMalthusians faced the same situation in the 1970s, right before the Green Revoltuon. However, as history has shown, these disastrous situations have been prevented, for the most part. However, evidence shows that, because of the context surrounding climate change and the strategy followed by many countries (free-riding seeing as a preferred strategy over international cooperation), the stakes seem to be higher this time.

Furthermore, even if a critical situation may be avoided, the reality is that the most vulnerable sectors of the global population are already facing some of the consequences of environmental degradation, through a loss of their livelihoods and increases in violence and conflict. This has also led to increases in migration, intensifying the vulnerability of these groups.

8.5 The rural-urban divide and migration

Urban planning

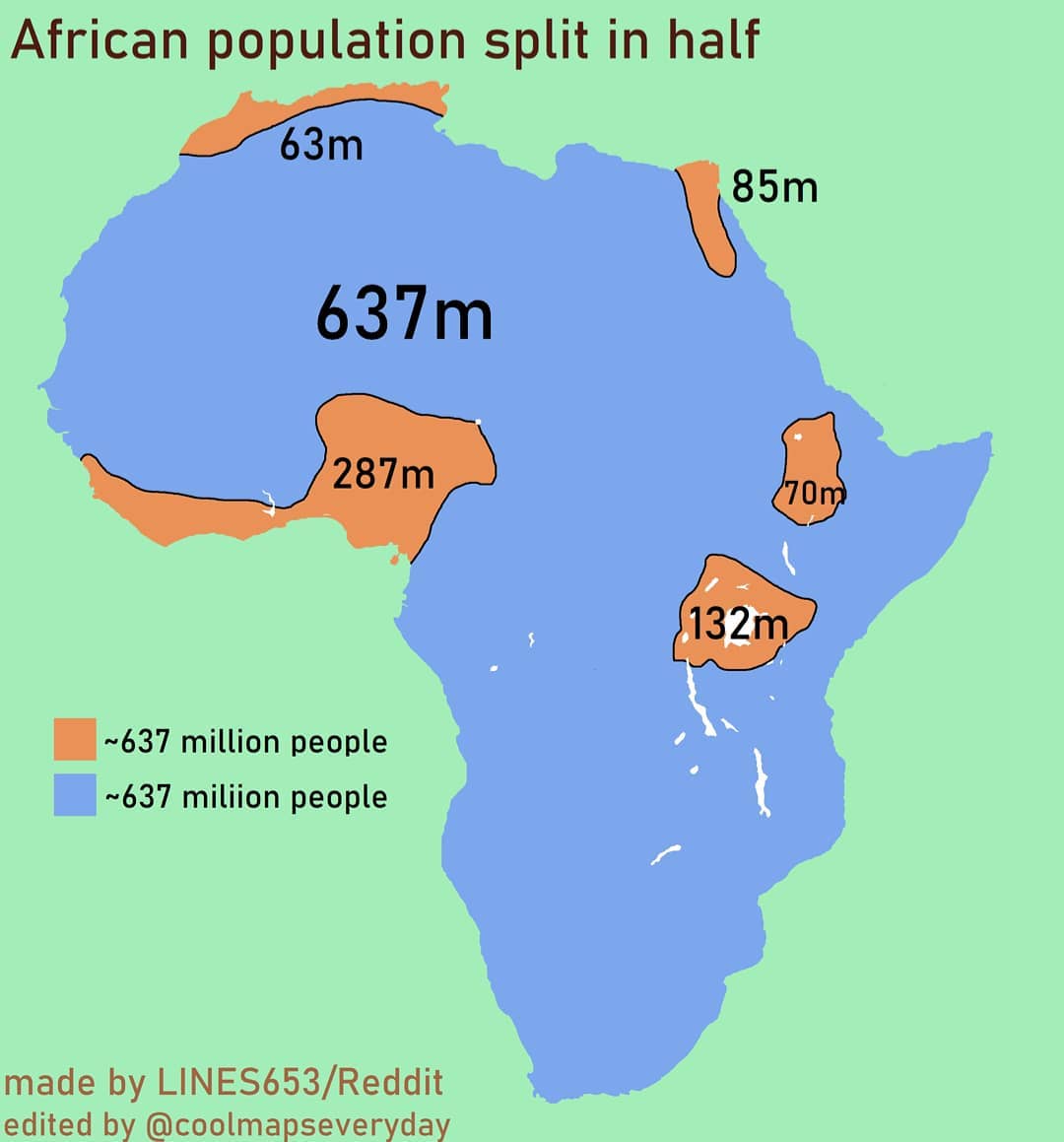

Figure 8.2: Source: Interesting maps

There is a clear rural-urban divide in a large share of low- and middle-income countries. This divide not only exists in terms of income disparities, but it also reflects in political participation, and on the provision of public goods.

In a pioneer work, Bates (1981) argued that African governments used marketing boards18 as a source of revenue, it extracted surplus from the agricultural producers and transferred that to fund industrial and urban development. This is because, contrary to urban workers, farmers cannot organize and protest. Urban workers will demand higher real wages (by keeping prices down) and have the capacity to revolt. These policies will not apply to elite farmers and will have access to duty-free imported agricultural inputs.

Stasavage (2005) proposes a similar argument, looking at tertiary education (college) vis-à-vis primary education. He shows how, as African countries started to democratize, public spending in elementary (primary and secondary) education started to increase, which is considered a public good. This allowed people in rural areas (the majority of the population in an African context) to access it. However, spending on tertiary education did not decrease. Why? Because otherwise, urban dwellers could revolt, as they are the ones that attend college for the most part.

Of course, this impact of urbanization can explain why, with an increase in people moving to cities, there has been a shift towards more civic participation (see, for instance, the protests in Khartoum and other cities in Sudan to call for the appointment of a civilian government and a public trial of Omar al-Bashir).

Urbanization has also led to the spread of African culture. As Barrett-Gaines (2005) argues, “cities in Africa are not simply colonial crossroads, but rather are quintessentially African; in them and because of them, Africans create new things”. This includes the spread of Afrobeats and African music19, African arts and even the recent arrival of Netflix’s Made in Africa section.

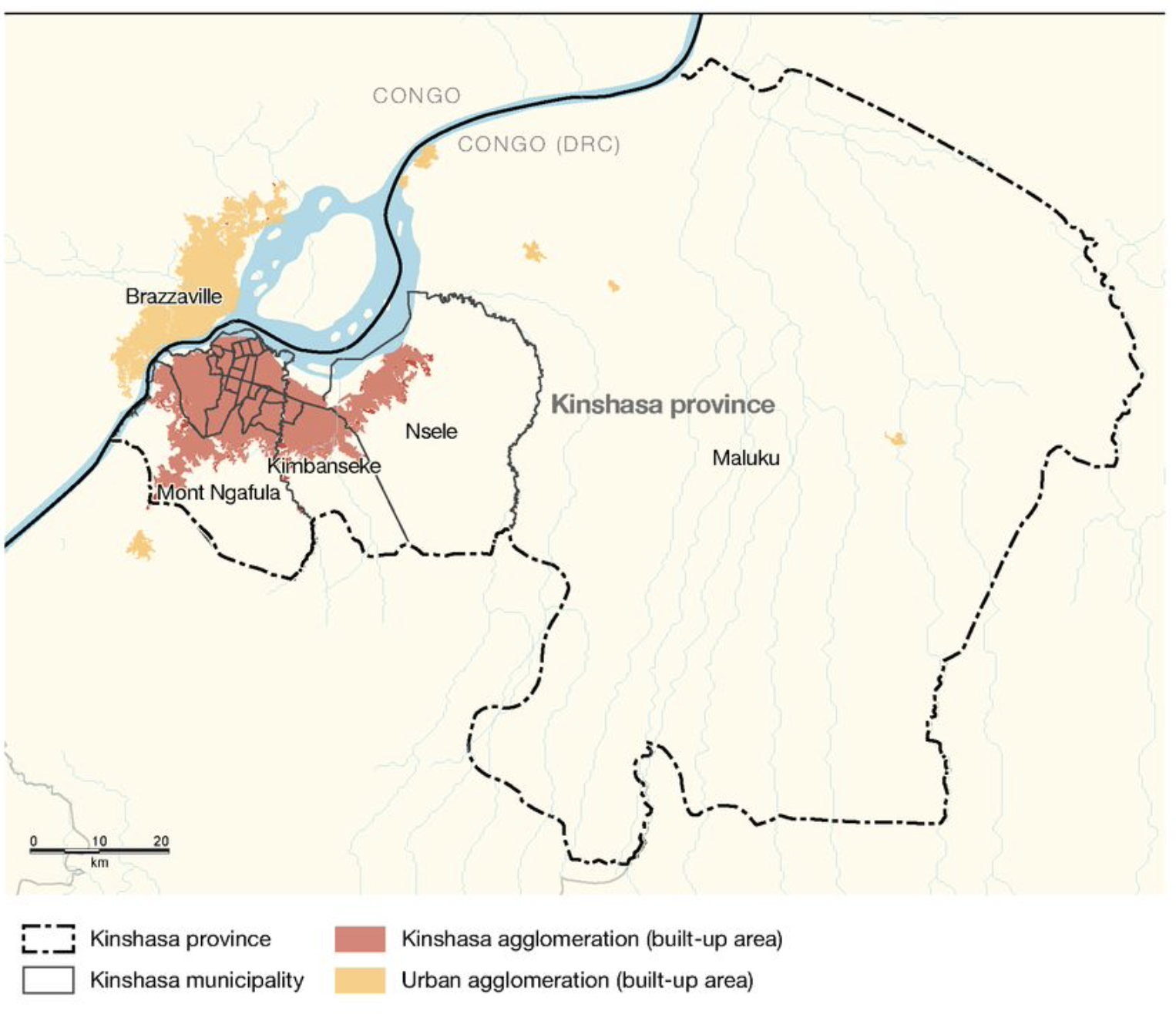

Urbanization, however, is also linked to many challenges. Most African cities were never formerly planned. Instead, they have been growing in a concentric and disorganized way, leading to issues related to public good provision, disaster prevention, mobility, and urban poverty, imposing difficulties for the development of these cities.

Titeca and Malukisa (2018), find that, for Kinshasa, one of the main challenges is linked to how elite connections determine the development path of the city in areas with weak state presence. They arrive in parts of the city where specific constructions are not allowed, and participate in these unlawful constructions, building new constituencies, at the same time. They bring public goods to the areas and show how the city’s development depends entirely on their will. Hence, the services are fragile and unpredictable.

Rigon, Walker, and Koroma (forthcoming, 2020) also touch on this issue by addressing the formal/informal categorization in Freetown, Sierra Leone. The authors show the political use of ‘informal’ to frame it as belonging to the poor but revealing the inability of the state to provide employment and social protection to these sectors of the population.

Even if urbanization is increasing, living in an African city is expensive, with the most expensive cities according to the Mercer survey (2020) being:

- Lagos, Nigeria

- Kinshasa, DRC

- Libreville, Gabon

- Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire

- Brazzaville, Congo

This is even if public good provision is unreliable in many cases, and mobility is complicated, with patched roads with continuous ditches and crowded and unsafe public transport.

Part of the difficulty of public good provision comes from the hardship of measuring urbanization: different countries have different thresholds and methods to measure what urban areas are. Furthermore, the lack of Census data and the unplanned growth of cities complicates the provision of public goods, without knowing where people live.

Figure 8.3: Kinshasa, the City-Region Source: OECD (2020)

Migration

Migration is possibly one of the least understood but most controversial topics and requires much more careful examination than the one we can give it in the course20. It is a topic closely linked to urbanization, as cities have two ways to grow: (1) a natural path or population growth (people born in the city); (2) migration. Currently, migration plays the most crucial factor in the growth of African cities.

Why do people migrate?

The gap between rural and urban areas may explain why people decide to move (temporarily or permanently) towards the urban areas. Using the Lewis model of development (1954), if there is a surplus in the agricultural sector, migration will transfer this surplus to other sectors where workers can obtain a higher average wage. This mechanism is also active in the case of international migration.

Although this may provide the primary motivation behind economic migration, this is not the only reason for migration. Another critical driver of forced migration is violence. Under this context, migration is the consequence of civil war or other forms of generalized violence. As conflict approaches the community, people decide to move to a different region, often within the same country (Melander and Öberg, 2009).

Can migration promote development?

Most of the research on this topic in development economics seems to support this argument, but with different nuances.

Bryan and Morten (2019) study the case of internal migration in Indonesia and find that “removing barriers to internal migration can boost a country’s productivity.” However, the authors provide some nuance as they state that the effects are modest and heterogeneous. This is because there is a selection problem in which cities are more productive since more productive persons choose to live in them.

For the case of China, Kinnan, Wang and Wang (2018) are more optimistic, showing that internal migration does not only promotes economic growth, but it also enhances the welfare of rural households. Similarly, for the case of Tanzania, Beegle et al. (2011) find that internal migration increases rural consumption.

Bryan et al. (2014) conduct an experiment in Bangladesh in which, randomly, they reduce the financial barrier of migrating by providing some households with cash equal to the cost of a bus ticket for one household member to migrate during the lean season. The authors find that those households where the member migrates enjoy higher consumption and are more likely to seasonally migrate in the following years.

When examining how migration impacts the community of origin and the host region, it is crucial to consider endogeneity factors (do migrants have more ‘grit’ and that explains their success?), as well as the migration causes (when do people prefer not to migrate?), and the consequences of migration for different sectors (is there a surplus of labor in the agricultural sector?)

8.6 Seminar Questions Module 5

8.6.0.1 Week 13:

- Based on the readings and our discussion, write a reflection on how identity shapes and is shaped by development.

8.6.0.2 Week 14:

Environmental degradation and development

- Why are people in low-income countries more vulnerable to the effects of climate change? What is the role of natural resources on promoting development?

8.7 Readings Module 5

8.7.1 Required Readings Module 5

8.7.1.1 Week 13:

Gender and Development

Tuesday, April 4- No in-session class. Instead, please watch: City of Joy. Make sure that you watch the 2016 documentary on Netflix.

Koko, G. et al. (2018).“Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer (LGBTQ) forced migrants and asylum seekers”. In Queer in Africa: LGBTQI Identities, Citizenship, and Activism. New York: Routledge.

Duflo, E. (2012). “Women Empowerment and Economic Development”. Journal of Economic Literature. 50(4) 1051-1079.

Evans, A. (2016).“The Decline of the Male Breadwinner and Persistence of the Female Carer: Exposure, Interests, and Micro–Macro Interactions”. Annals of the American Association of Geographers, 106(5), Pp. 1135-1151

World Bank (2011). “World development report 2012 : Gender equality and development” World Bank Publications. Chapter 2

Culture, Religion and Development

Deng, F. (1997).“Ethnicity: An African Predicament”. Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution

Nunn, N. (2012). “Culture and the Historical Process. Economic History of Developing Regions. Vol 27(S1).

8.7.1.2 Week 14:

The ‘curse’ of natural resources

Savoia, A. and Sen, K. (2021). “The Political Economy of the Resource Curse: A Development Perspective”. Annual Review of Resource Economics. 13: 203-223.

Dercon, S. (2022) “Nigeria and the Democratic Republic of the Congo: Not Enough Oil or Diamonds”. In Gambling on Development: Why Some Countries Win and Others Lose. London: Hurst.

Environmental degradation and development

Thursday, April 13- No in-session class. Instead, please watch one of the following documentaries: Virunga, Food Inc., When Two Worlds Collide, The True Cost.

Marijnen, E. and Verweijen, J. (2019). “The charcoal challenge in DRC’s Virunga”. London: LSE

Sigelmann, L. (2019). The Hidden Driver: Climate Change and Migration in Central America’s Northern Triangle. American Security Project.

8.7.1.3 Week 15:

The rural-urban divide and migration

Moss, T. and Resnick, D. (2018). African Development, 3rd. Ed. Boulder: Kynne Rienner- Chapter 11

Toochi Aniche, E. (2020). “Migration and Sustainable Development: Challenges and Opportunities”. In Moyo, I., Nshimbi, Ch. and Laine, J. (Eds.) Migration Conundrums, Regional Integration and Development. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

8.7.2 Suggested Readings and Resources Module 5

Culture, Ethnicity and Development

- Lopez-Claros, A. and Perotti, V. (2014). “Does Culture Matter for Development?”. Policy Research Working Paper 7092. Washington, D.C.: World Bank

- Giuliano, P. and Nunn, N. (2017). “Understanding Cultural Persistence and Change”. NBER Working Paper 23617.

- Spolaore, E. and Wacziarg, R. (2013). How Deep Are the Roots of Economic Development?. Journal of Economic Literature. Vol. 51(2). pp. 325-369

- Depetris-Chauvin, E., Durante, R., Campante, F. (2019). Building Nations Through Shared Experiences: Evidence from African Football. Working Paper

The rural-urban divide and migration

- Paller, J. (2019). “Everyday Politics in Urban Africa”. In Paller, J. Democracy in Ghana: Everyday Politics in Urban Africa. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

- OECD, (2020). “Africa’s Urbanization Dynamics 2020: Africapolis, Mapping a New Urban Geography”. West African Studies. Paris: OECD.

- Terrefe, B. (2020). “Megaprojects in Addis Ababa raise questions about spatial justice”](https://theconversation.com/megaprojects-in-addis-ababa-raise-questions-about-spatial-justice-141067?utm_term=Autofeed&utm_medium=Social&utm_source=Twitter#Echobox=1592925570). The Conversation, June 23, 2020

- Clemens and Postel (2018). “Deterring Emigration with Foreign Aid: An Overview of Evidence from Low-Income Countries”. Population and Development Review. Vol. 44(4). pp. 667-693

- Video: “Spotlight on Migration and Institutions with Kaivan Munshi of the University of Cambridge”

- Some data and reports: Migration Policy Institute

- Movies to watch: “Lionheart”; “The African Doctor”; “Atlantics”

You can slightly deviate from these questions, with my previous approval.↩︎

“American should […] draw on our country’s vast storehouse of technical expertise to help people overseas help themselves in the fight against ignorance, illness, and despair.” (Brooks, 2017)↩︎

Sir Arthur Lewis was born in St. Lucia, and until today, he is the only Black economist that has been laureated with a Nobel Prize in economics.↩︎

Many times this only worked in discourse, as we will see in future sessions↩︎

This exercise shows you how to calculate the three components of the HDI. It will help you to understand the multidimensionality of development and poverty better.↩︎

Note that these figures represent the context before Covid-19.↩︎

Kinship norms are related to cousin marriage, clans, and co-residence that fostered social tightness, interdependence, and in-group cooperation↩︎

The specific argument was that with the collapse of the Soviet Union, the last ideological alternative to liberalism had been eliminated (He, of course, did not take the events in Tiananmen Square into account). The argument has been criticized for its Eurocentric approach, and it must be said that the entirety of the argument involved the creation of an effective state, the rule of law that binds the sovereign, and accountability. Fukuyama has updated his argument, focusing on the value of institutions.↩︎

The index was constructed following Stasavage’s self-assessment of democracy index, using data from the Round 7 of the Afrobarometer.↩︎

Disclaimer: In some instances, ACLED records one single event that spread across different places as different events.↩︎

This is not to say that these countries do not face tensions and that the situation is not fragile, as there are many unresolved issues↩︎

According to Cramer, Sender, and Oqubay (2020), Africa had a delayed and weak implementation of the Green Revolution, mainly because of the configuration of its agricultural land.↩︎

It is argued that the increases in productivity lead to economic growth if the sector is driven by small farms, as it is the case in Asia (Mellor, 1976).↩︎

Edmonds and Pavcnik (2005, 2006) do cross-country analyses. They argue that claims on trade exacerbating child labor are inconsistent with the evidence.↩︎

Remember the podcast “Urban Africa”, where the interviewer says “everything is being built by the Chinese”?↩︎

The ethics behind these RCTs is quite controversial, as you can see here and here↩︎

In Ivory Coast, for instance, rainforest cover has been reduced by 80% since 1960 (The Guardian, 2017)↩︎

Marketing boards are institutions that are in charge of buying cash crops directly to producers (at established prices) and then exporting them (at world prices). The boards were highly prominent in West Africa. Most of them had either disappeared or transformed. Ghana’s cocoa board is still working, but has transformed its operation.↩︎

More on African music can be found on Music Africa↩︎

I teach a 4-credit course on the Economics of migration in the January term. The course satisfies the CUL4-North America cultural perspectives requirement.↩︎