Chapter 4 Module 1: Development

Figure 4.1: Kinshasa, DRC (2018)

Topics Covered:

- What is development?

- Approaches and theories on development

- Poverty and Poverty Traps

- Income Inequality

4.1 What is development?

In the first Module, we will analyze different perspectives of development that have been proposed before adopting the definition that this course will take. Overall, we will see that the main focus of this course is to understand how different events, policies, and practices affect the well-being of people living in low-income countries.

In economics, development has been seen as a way to attain an adequate living standard for the people. Traditionally, this has translated into material well-being, and therefore, economic growth has been at the center of the analysis, and multiple policies have been implemented to improve the economic growth rates of countries around the world. This required an approach focused on the structural configuration of economies.

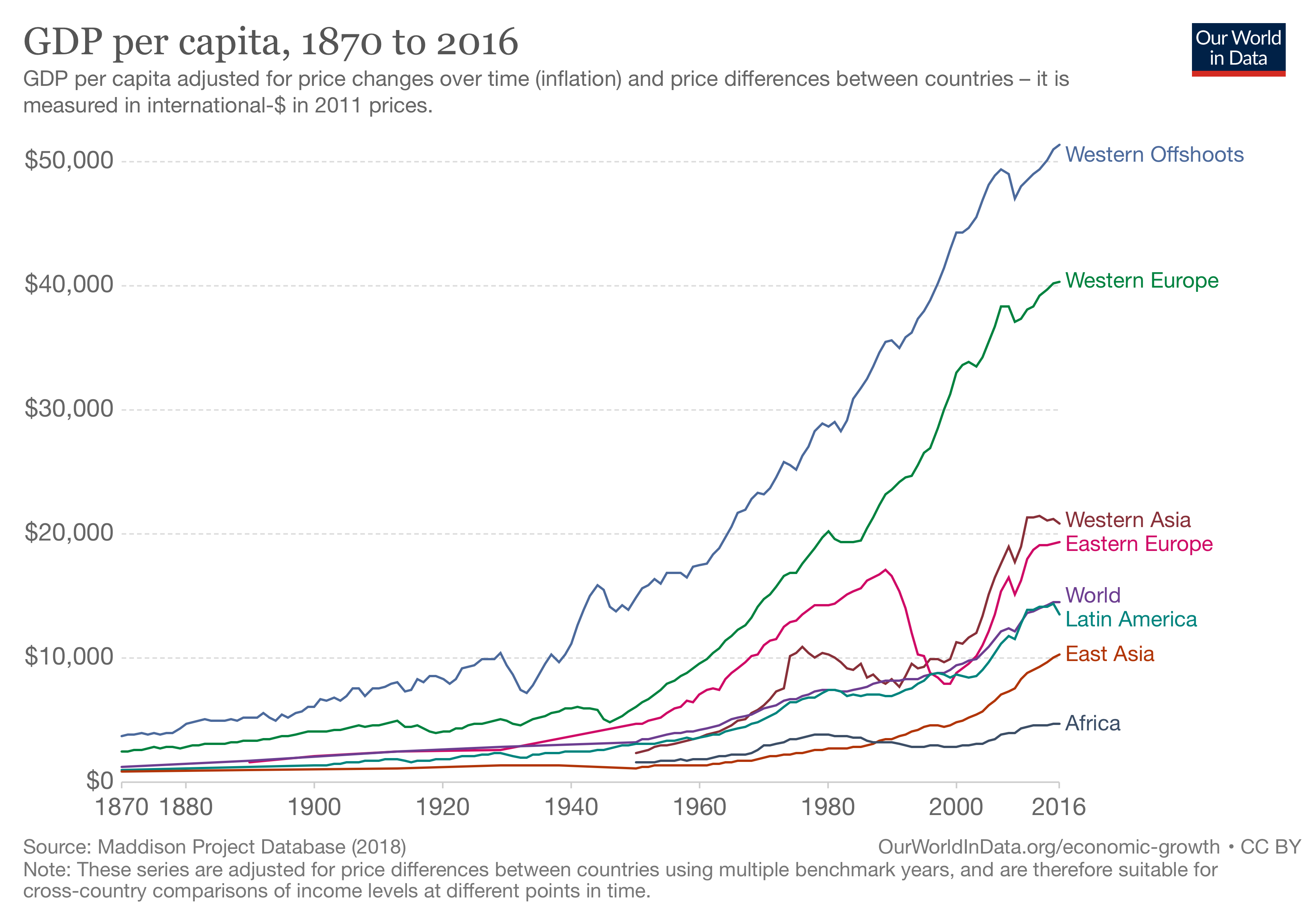

Figure 4.2: Source: Our World in Data (2020)

However, this approach to development has brought some criticism. This is because, under this vision, development – understood as the * “change that increases capital in social, financial and political terms through policy and planning”* – (MacNeill, 2017) is tacitly linked to ‘modernity’ and may lead to a Eurocentric vision of what the world should look like. This creates a perspective in which those that are developed are the ones that possess knowledge and rationality. Therefore, If we understand development in which material well-being equates to the possession of rationality and knowledge, we would be promoting a discourse that creates a power relation between what we consider as developed and underdeveloped. This system of modern imperialism forces poor countries to access a system to ‘boost their development’ to avoid being marginalized, even if this has negative consequences for their socio-economic and cultural structures (Javed, 2018).

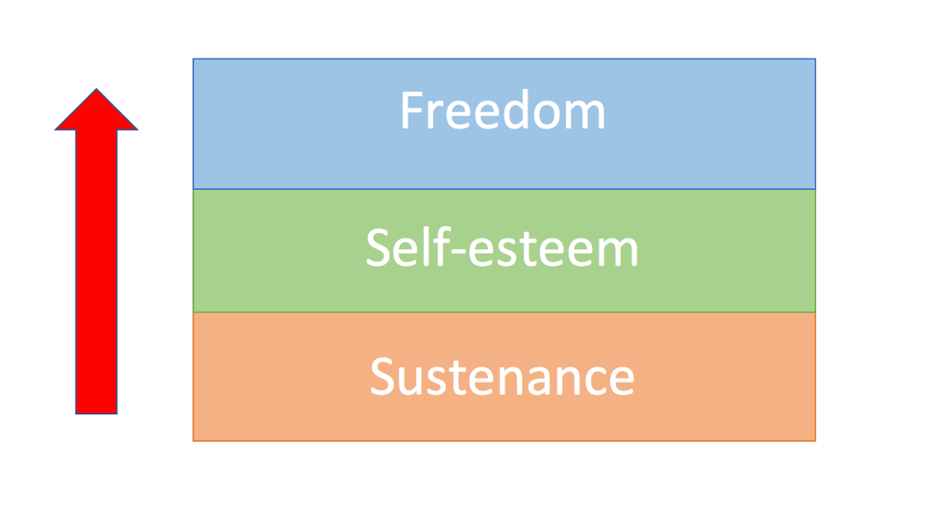

Therefore, a vision of economic development that just encompasses economic growth, structural changes in the patterns of production, and technological improvement is limited if we understand it as a social phenomenon (Kuznets, 1966; Grabowski, R. et al, 2015). It should then include other elements such as institutional improvement and the enhancement of human welfare (Grabowski, R. et al, 2015). As Amartya Sen puts it, development is a “process of improving the quality of all human lives and capabilities by raising people’s levels of living, self-esteem, and freedom.”

Figure 4.3: Development as Freedom, Amartya Sen (1999)

This requires considering the specific conditions of low-income countries and adapting the concept of development and its approaches accordingly. This implies that ideas that have been implemented in the West do not necessarily apply in non-Western countries, but it also means that the same approaches may not automatically be followed in different regions because the contexts are different. This has required that development economics become more “comprehensive and analytical” (DeJanvri, A. and Sadoulet, E.).

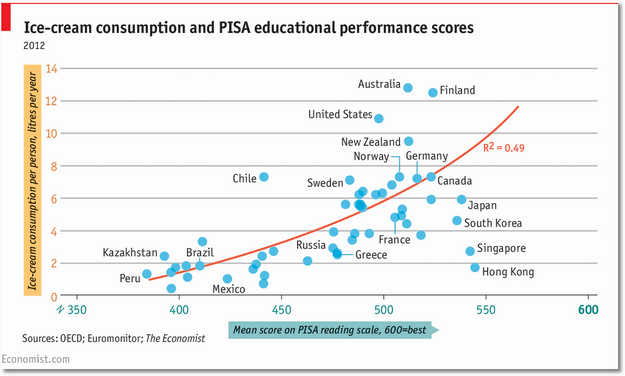

Under this approach, development has become more ‘specific’, even if the emphasis is also on rediscovering ideas that can connect micro issues with macro factors to improve people’s well-being in a sustained way. This requires adopting a long-term perspective and focusing on identifying causal effects (we will see how correlation does not mean causation and that endogeneity is constantly an issue), which we will do in the third section of the course.

Overall, the field of development economics, and more specifically, macro-development, in which this course is set, has sizeable potential policy implications, which will motivate many debates in the course. However, whereas these policies could improve the livelihoods of the population across the world, they can also generate perverse effects if the cultural, political, and institutional context is not taken into account. In the course, we will embrace an interdisciplinary vision that takes into account these factors to then explore how we can use economics to explore how different policies, practices and events affect the well-being of people in low- and middle-income countries.

Some of the questions that we will examine during the course are:

- Can we envision a more sustainable vision of development?

- Do institutions matter for development?

- What was the role of colonization on development?

- How can agriculture/trade/financial systems affect development?

- Does foreign aid benefit the recipient countries?

- How do culture and economics interact?

4.2 Theories on Development

Linked to the different visions on development, different theories have been proposed to explain development.

The first economic explorations on development focused on market structure (Adam Smith), on the configuration of the population (Malthus) and the availability of capital and labor (David Ricardo). This approach to development centered on the industrialization process happening at the time (18th.-19th Centuries) in Europe and the United States, and it is at the base of some of the most critical concepts in neoclassical economics.

In modern times, the end of World War II signified the reconstruction of Europe, the independence of African countries, and a different focus on development. In 1947, president Truman said during his inaugural speech that it was the responsibility of rich nations to ‘develop poorer countries’ in their image 2. This also coincided with the beginning of the Cold War, in which the so-called “Third-World countries” were used as a proxy in the conflict.

During this time, underdevelopment was seen as an initial stage in the industrialization process. The Western top-down approach followed classical economic theory, focusing on liberalization, and the accumulation of capital. Modernization theory aimed to identify the factors that could allow countries to go from a ‘traditional’ mode of production into industrialization, just as rich countries had done. This theory assumed a linear process of development and was deeply centered on free-market precepts. Similar to this, ** Rostow’s “Stages of Economic Growth: A Non-communist Manifesto”** proposed that economic development of poor countries would follow a set of 5 stages that would allow all countries to go from being a traditional society to an economy centered on mass consumption.

During the 1960s and 1970s, a resistance movement started in Latin America and the Caribbean with the emergence of Dependency theory. This theory emphasized that the Western-imposed ‘development’ policies have helped promote the West’s interests while keeping the poor countries more impoverished. In theory, resources flow from the periphery (poor countries) towards the core (rich countries), benefitting the latter at the expense of the former. The leading proponents of this theory were Raul Prebisch in Argentina and Fernando H. Cardoso in Brazil.

An additional theme emerged at the time, as many low-income countries were characterized by a dualistic economy, in which the ‘traditional’ and ‘modern’ sectors coexisted. According to Nobel Laureate in Economics, Sir Arthur Lewis3, the proponent of the Dual-Sector theory, an unlimited supply of labor derives from population pressure, keeps wages in the subsistence sector down. In contrast, the modern sector profited from higher returns to capital. According to this model, development would come from the absorption of labor from the traditional sector into the modern manufacturing industry. The validity of this model has been called into question several times, even if its impact to understand general patterns of development has been substantial. Particularly, the model has been criticized for underestimating the importance of small-scale agriculture, as more intensive methods were adopted in the agricultural sector with the advent of the Green Revolution. However, the Dual-Sector Theory has also been helpful to examine movements across sectors and rural-urban migration. Similar theories used economic dualism and indicated that development started with ‘unbalanced growth’ in which one center of economic strength would create a centrifugal effect for the development of others. Among these models, we have ** Myrdal’s ‘cumulative causation’ principle** and ** Hirschman’s ‘unbalanced growth’** model.

During the 1980s, a new approach emerged following the conservative economic approach taken by president Ronald Reagan in the U.S. and prime minister Margaret Thatcher in the U.K. This Neoliberal ideology set the market principles as the driving mechanism of development. As many low- and middle-income countries struggled with high levels of indebtedness and structural issues, a series of policies were homogeneously promoted by the international development agencies (World Bank and IMF). These policies included the removal of high tariffs, convoluted regulation, the privatization of multiple sectors, and the liberalization of the financial sector. This market deregulation disregarded the failures that existed in many markets and the specific contexts in which they were applied. While it is true that these countries struggled with structures that were inefficient and ineffective, the solutions proposed did not consider the specific needs of each country to solve these inefficiencies nor the market asymmetries that existed.

In recent years, new approaches have been included under mainstream theories or have been accepted as alternative theories of development. Participatory development has been proposed as a way to engage the local populations in development projects. Although highly popular among development practitioners, this approach has also been criticized as it imposes more struggles to the local population and involves unequal relations of power, in which the way development happens is imposed from the outside.

4.2.1 African Approaches

African visions of development emerged even before these countries got their independence. In that regard, African anti-colonialists and leaders, such as Julius Nyerere in Tanzania (president between 1961 and 1985), Kwame Nkrumah in Ghana (president between 1960 and 1966), Ethiopia’s Emperor Haile Selassie (1930-1974), among others, envisioned development from a nationalistic perspective that promoted African values and pan-Africanism.

These perspectives on development combined economic and political elements and emphasized the separation from the former colonizers and Western influence4. This development vision also required national unity, which in turn generated some inequalities among groups and prevented political competition.

4.3 Measuring development and poverty

Economic development is usually associated with GDP and GDP per capita. Although useful as an international standard, these measurements tell us little about the well-being of the population. Since the definition of development has been broadened, the emphasis has been put on increasing the dimensions to assess the population’s welfare and measure the scale and depth of poverty.

There are two approaches to examine poverty. The first one is the welfarist approach and indicates that a person is poor if her attained economic level is below a threshold (poverty line). Poverty in this way can be measured in an absolute way (what % of the population is below that threshold) or relative (differences vary depending on the real income in different places) (Ravallion, M. (2020)).

The second approach is multidimensional, and it is based on Sen’s capabilities approach. It understands poverty as the deprivation in different dimensions: physical, mental, education, social life, environmental quality. These dimensions are at the base of the Human Development Index 5 , which in turn helps to attain the Sustainable Development Goals.

For measuring poverty rates, two different methods can be used. The first one is to look at the income of households. The main issue with this method is that many persons in low-income countries do not receive standard salaries, but their income diverges widely across a year. This is why the second method assesses a household’s welfare by looking at its consumption levels. The main issue with this method is to decide how (if) housing is included, as most of the time, people in low-income countries do not pay for it, at least in rural areas.

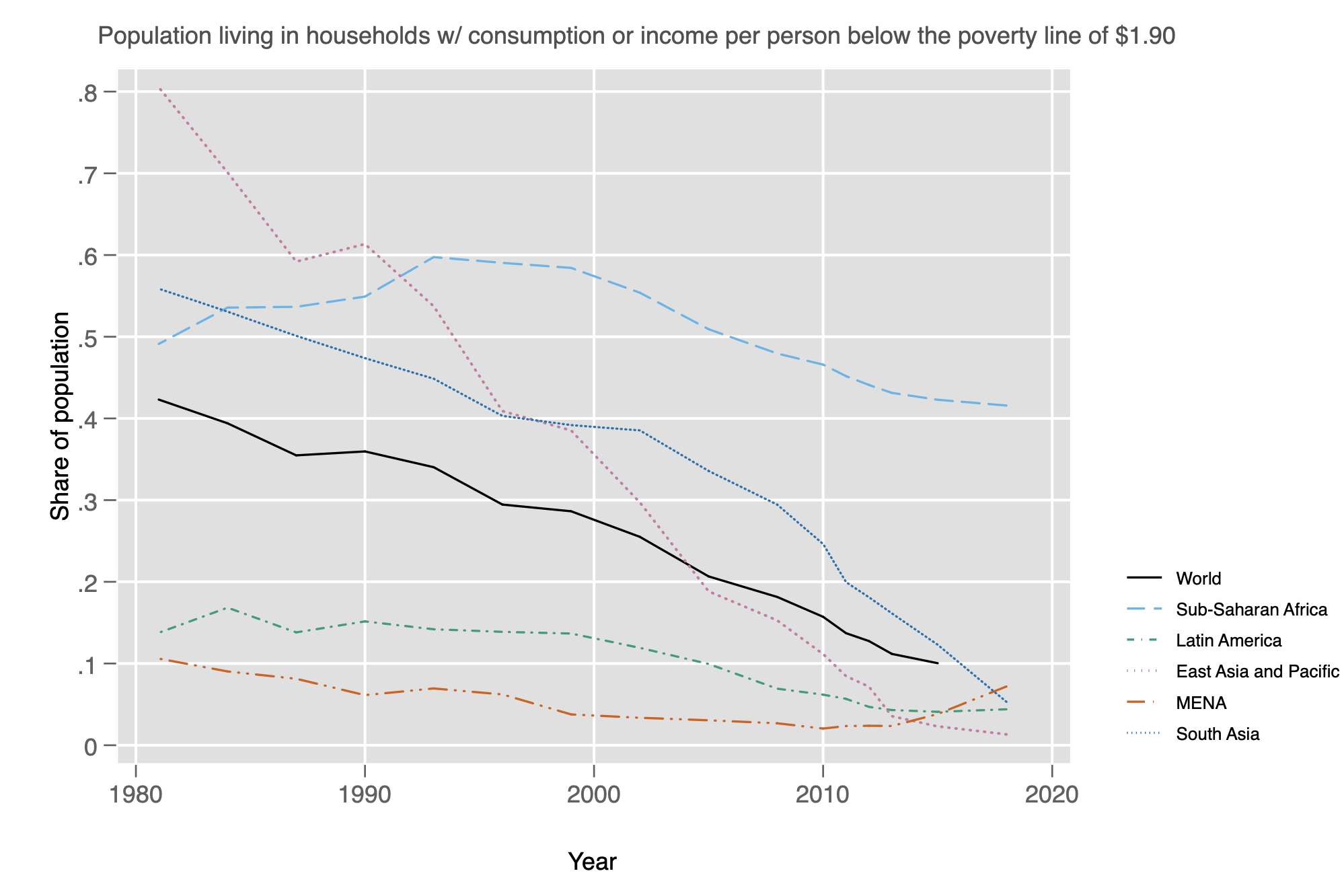

How to set the poverty line? To calculate the incidence of poverty across countries and time, it is vital to set a threshold that takes into account differences in consumption patterns across countries. Currently, this threshold is set at $1.90 US dollars using purchasing power parity exchange rates (PPP). As shown in the graph below, the incidence of poverty has decreased across the world. However, the rates of change have been higher in certain regions than in others. Sub-Saharan Africa has the most significant shares of poverty (measured as poverty headcount) in the world.

Figure 4.4: Source: Elaborated with data from the World Bank (2020)

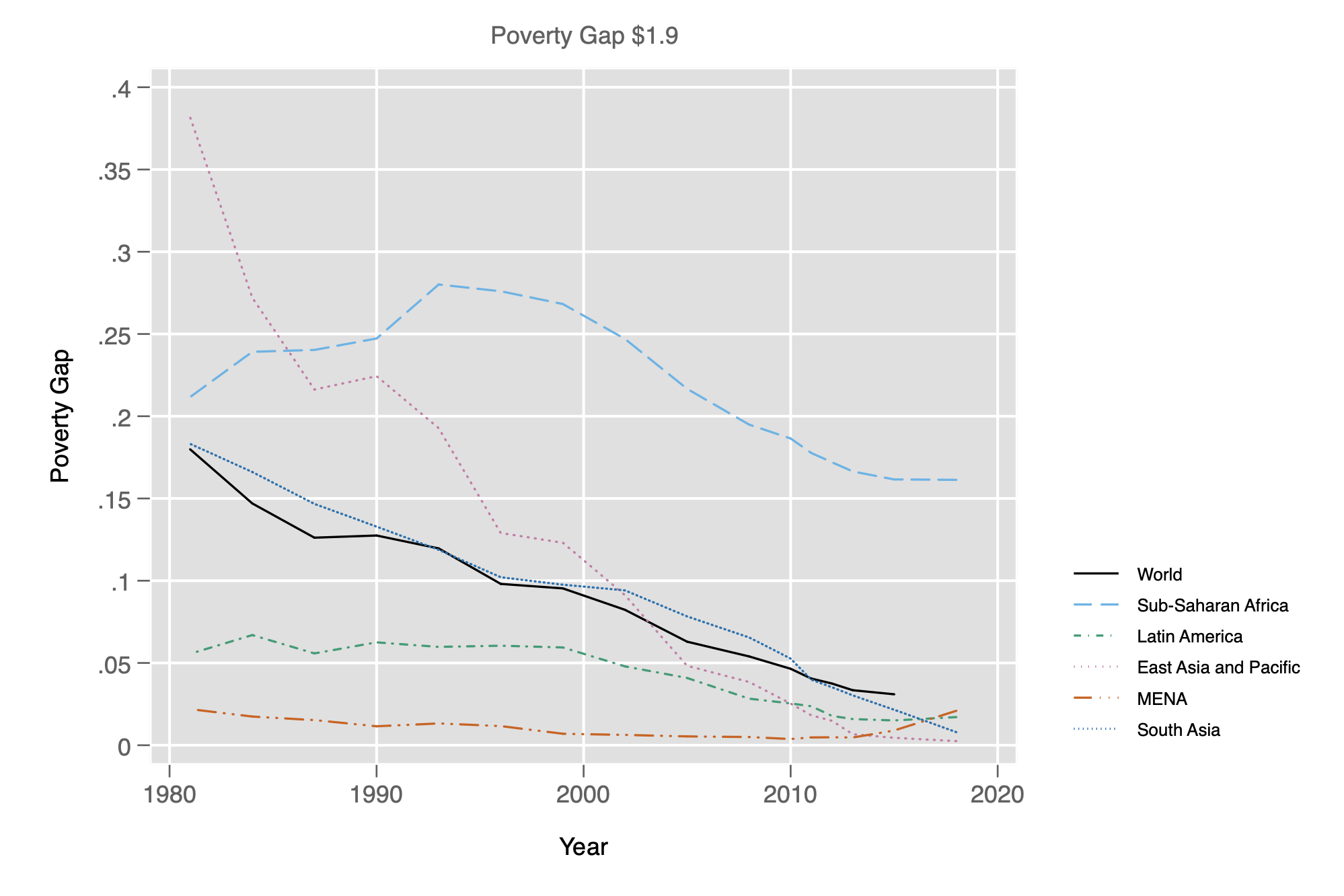

Other than the poverty line, the poverty gap is also relevant. It allows us to measure the mean shortfall of income from the poverty line. This index measures the intensity of poverty. It looks at the average distance from the poverty threshold among the population. Across the world, this gap has been decreasing, even in Sub-Saharan Africa, although at a lower rate, as the shortfall (the average distance from a mean of zero) is about 16.13%6.

Figure 4.5: Source: Elaborated with data from the World Bank (2020)

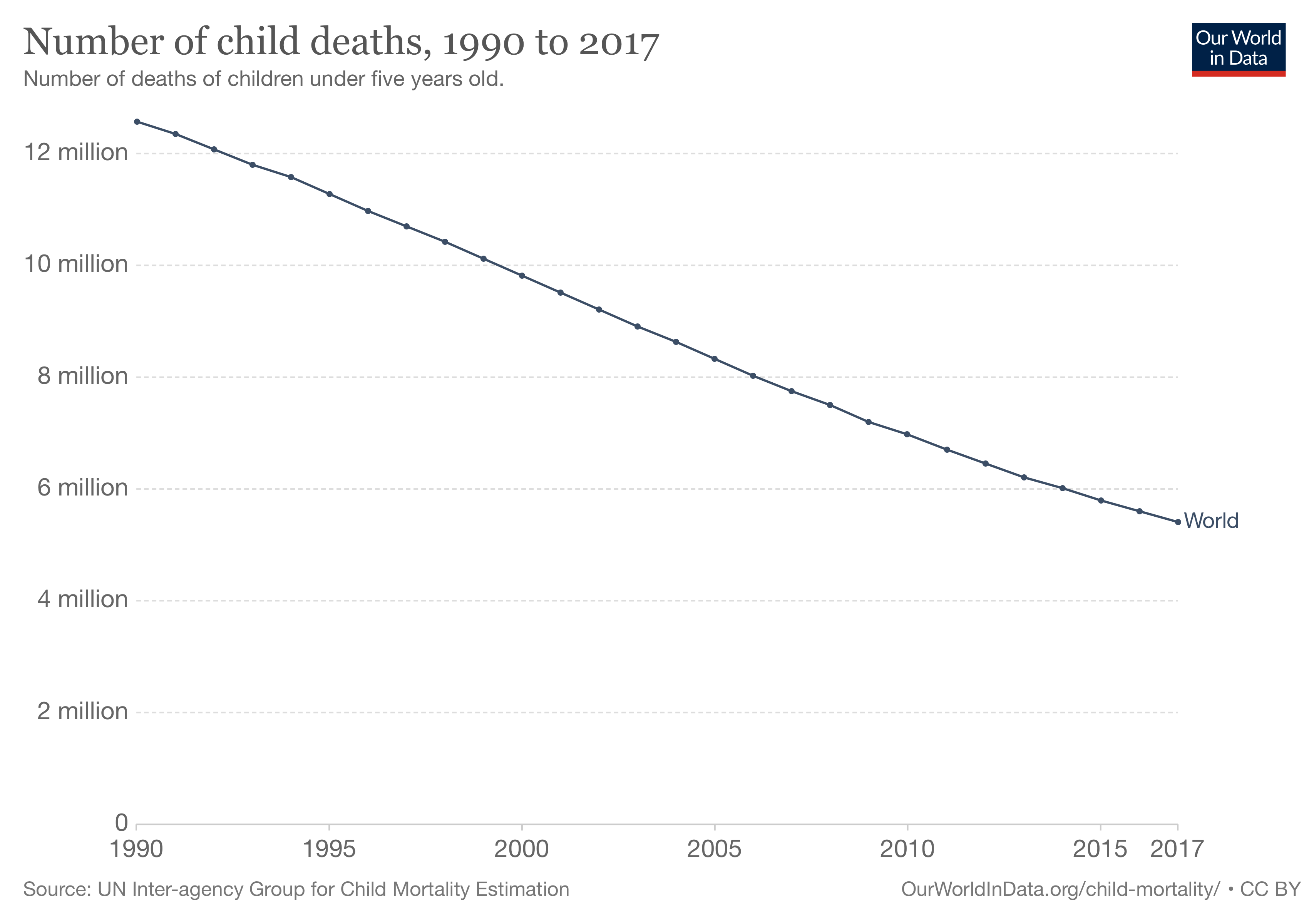

If multidimensional poverty is examined, nutrition, infant mortality, and educational attainment are some of the elements that are measured. In this case, we also see that the conditions worldwide have improved, even if we are still far away from the goals established by the SDG’s. For instance, whereas the goal for infant mortality is to attain a rate lower than 2.5% by 2030, currently, 3.9% of children die before reaching the age of 5 (15,000 children die every day).

Figure 4.6: Source: Our World in Data (2020)

4.4 Is there a poverty trap?

To eradicate poverty is the central goal of development economics. This is the primary goal of the SDGs and the moto of the World Bank. Nevertheless, to eradicate it, it is necessary to understand why people are poor first, which is a rather complicated endeavor.

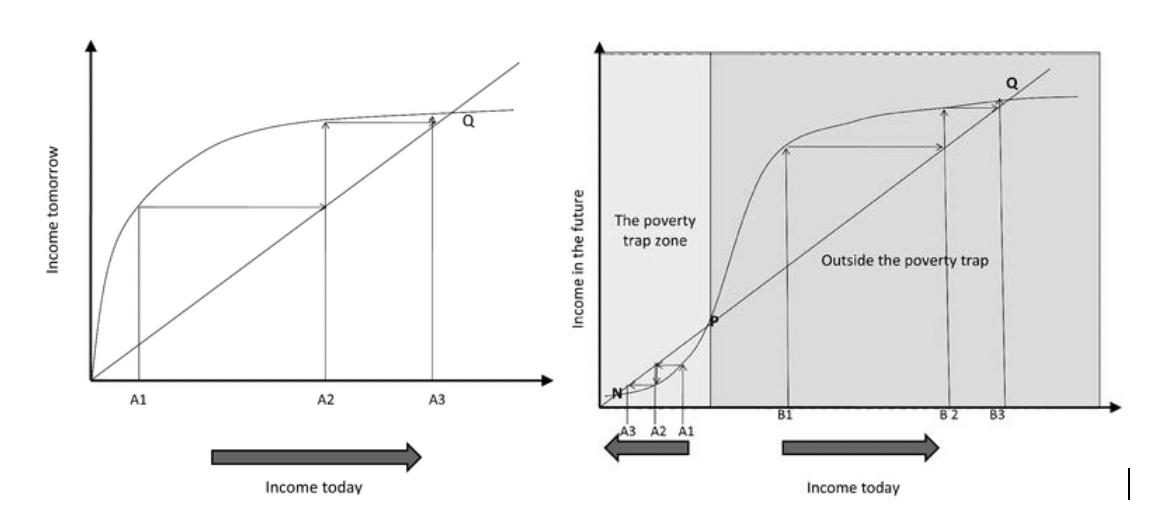

Broadly, there are two main viewpoints on this. The first one argues that everybody in the society has the same opportunity to thrive and that the divergence in outcomes represents the differences in intrinsic characteristics. The opposite view claims that the poor are constrained by their environment and do not have the same opportunities, choosing low-productive activities instead. At the macro level, these two opposite views would show if countries converge at some point (Solow, 1956) or if instead multiple equilibria –steady states– exist (Rostow, 1960; Myrdal,1957; Myrdal, 1968).

Figure 4.7: No poverty trap vs. poverty trap. Source: Banerjee and Duflo (2011)

The implications and the way to approach the two perspectives are quite different. Suppose people (or countries) are indeed in a poverty trap that prevent them from becoming more productive. In that case, policies that could push them out of this condition will provide a sustainable solution to end poverty. This is the elemental claim behind foreign aid.

Looking empirically at this issue is quite complicated, as the underlying mechanisms are not observable (we cannot observe ability), and the consequences are similar under both contexts. Furthermore, there are many ways in which we could think that people (and countries) could be caught in traps, as explained below. Some attempts have been made to test this.

Using country data, Easterly (2006) tests a limited version of poverty traps by looking if “the poorest countries are stuck in stagnation (…), and this stagnation is inevitable in the absence of aid.” He shows how different countries at the bottom of the income spectrum have shown periods of rapid growth at some point without the presence of aid. This goes against the hypothesis of poverty traps. Easterly concludes that the issue may be more complicated than initially presented, and therefore, a “Big Push” sort of policy will not be sufficient for a country’s ‘takeoff.’ This is not to say that he dismisses the idea of poverty traps. However, he argues that simplistic explanations focused on zero growth of individual countries and the need for Big Pushes may be a misinterpretation of what poverty traps are, of the theoretical models, and the experience of rich countries.

This approach is supported by Kray and McKenzie, (2014) who argue that the idea of poverty traps has motivated “Big Push” policies to attain a different equilibrium than the one’s countries are in, but find little evidence for a situation with zero growth, even among the poorest countries. They also indicate that there is little evidence on this type of poverty traps at the individual level.

A recent working paper by Balboni et al. (2020) empirically tests for the presence of poverty traps at the individual level, using data from a program in Bangladesh in which a group of poor women got a massive asset transfer. The study points out to the existence of poverty traps, in which households that are far below the poverty threshold are trapped in poverty even with the presence of the “Big Push,” but households that can pass this threshold attain a higher income bracket, allowing them to switch occupations to more productive ones. This would indicate that the effect of a program implemented (the “Big Push”) will depend on the distance between the poverty threshold and the position of a household.

These findings support other recent empirical estimations on poverty traps, like those obtained by Scott (2019) and Lybbert et al. (2004) in rural Ethiopia. Still, empirical evidence on poverty traps and the effectiveness of programs to assist households in surpassing it is not clear. It is often contradictory, as we will see later in the course.

One important aspect of poverty traps is that they explain poverty’s self-perpetuation (“poverty begets poverty”). At the macro level, this means that an economy could be better if the initial condition were better. Nevertheless, this is not the same as indicating that the divergence in long-run performance among countries is due only (or mostly) to the differences in their initial conditions (Matsuyama, 2008). The same explanation could be mirrored to explain differences among households or individuals. It is also important to acknowledge that poverty (or poverty traps) is multidimensional, and different mechanisms are interacting together and preventing development (Kray and McKenzie, 2014).

At the same time, even if a poor household or country is not in a poverty trap, this does not mean that programs to improve their conditions are not useful, as this could accelerate their transition to equilibrium (steady-state) and improve their wellbeing.

4.4.1 Mechanisms behind Poverty Traps

Poverty traps could emerge because of multiple reasons. Some of the mechanisms that have been explored in the literature are now listed.

- Saving-Based poverty traps: Countries or households may be too poor to save, which means that they cannot invest and therefore, cannot accumulate capital (assets), creating a vicious circle.

- Market-size and division of labor: Advanced technologies that produce economic growth require the use of advanced inputs. However, these inputs are not available in poor countries, pushing them to focus on less specialized technologies that do not produce economic growth.

- The nutritional poverty trap: Poverty can be self-reinforcing because individuals do not have the physical strength to do productive work, which in turn prevents them from earning enough to alleviate their condition.

- Credit and financial market constraints: In a context where market imperfections may limit the number of individuals can borrow, and the production technology may be nonconvex, with low levels of investment leading to low returns, only a few individuals can become entrepreneurs, with the rest choosing subsistence activities. At the macro level, this may also lead to a limited set of financial assets, reducing the opportunities to diversify risk.

- Demographic trap: Gains in income will be absorbed if high fertility rates persist, leading to a cycle of high fertility and low human capital.

4.5 Income Inequality and Development

In recent years, much attention has been put on the effect of inequality on development. For the most part, inequality has referred to the distribution of income across different sectors of the society. Although many have challenged the attention put on how income is distributed across the society, evidence has shown that this has important economic implications.

First, by focusing on inequality is possible to notice what factors have contributed to the **success* of certain groups over others. Beyond outcomes, the emphasis of the research on income inequality has shown how those with the highest incomes have much better opportunities, reducing the credibility of theories that put effort at the forefront or that push the ideals behind trickle-down economics.

Some examples of this research come from Thomas Piketty, who wrote a seminal book called Capital in the Twenty-First Century (2013), exploring wealth and income inequality paths in the U.S. and France. Branko Milanovic has also focused on global inequality issues, showing the forces behind income inequality.

4.5.1 How to Measure Income Inequality?

The way economists and statisticians measure inequality involves the following steps:

- Order the population according to ascending income levels

- Divide them into groups, either using quintiles (fifths) or deciles (tenths)

- Determine what proportion of total national income is received by each income group

- Obtain the ratio of the income received by the group at the top and those at the bottom.

Example

The following Table shows the income of 10 individuals, representing the entire population of a country:

| Individual | Income (USD PPP) | Share of total income | Quintile |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 200 | 1.33% | 1 |

| 2 | 3,250 | 21.67% | 5 |

| 3 | 500 | 3.33% | 2 |

| 4 | 350 | 2.33% | 1 |

| 5 | 1,500 | 10.00% | 4 |

| 6 | 1,240 | 8.27% | 3 |

| 7 | 2,190 | 14.60% | 4 |

| 8 | 725 | 4.83% | 3 |

| 9 | 545 | 3.63% | 2 |

| 10 | 4,500 | 30.00% | 5 |

| Total | 15,000 | 100.00% |

When obtaining the ratio of the income obtained by the top 20% vs. the bottom 40%, we observe that it is equal to 4.86, which means that the top 20% earners in this economy get about 5 times the national income of the 40% bottom earners.

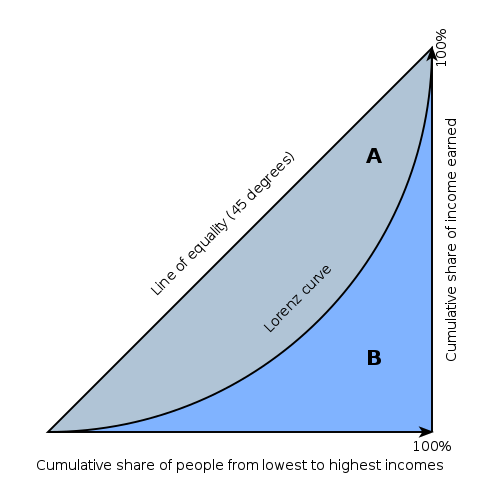

4.5.2 The Lorenz Curve and the Gini Coefficient

Another way to measure income inequality in a society is with the Lorenz Curve. This graphical representation shows the cumulative distribution of national income (vertical axis) gathered by different sectors of the population (horizontal axis).

Figure 4.8: Wikipedia (2022)

The diagonal shows the hypothetical scenario where the percentage of income received is exactly equal to the percentage of income recipients (for example, 50% of the population receive 50% of the national income). In this case, we have perfect equality.

The Lorenz Curve shows the deviation from this hypothetical case. The bigger the separation between this curve and the diagonal, the greater the degree of inequality represented.

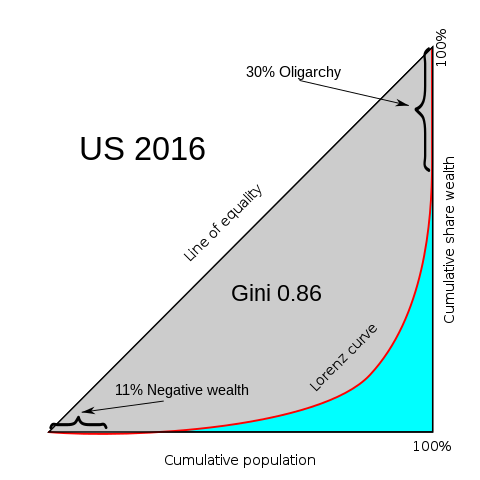

4.5.3 The Gini Coefficient

The Gini Coefficient is the most widely measure of income inequality within a society. It measures the ratio of the area between the diagonal and the Lorenz Curve divided by the total area of the half-square in which the Curve lies.

Figure 4.9: Wikipedia (2022)

\[\begin{equation} Gini= \frac{\text{Grey Area}}{\text{Total Area}} \end{equation}\]

4.6 Seminar Questions Module 1

4.6.0.1 Week 2:

What is development?

- How should we understand development? How is it different from economic growth?

- Build your own definition of development

4.6.0.2 Week 3:

Poverty, Inequality and Development

- How are poverty, inequality and development connected?

- Did China escape the poverty trap?

4.7 Activities Module 1

- We will construct a definition of development based on your answers and feedback on the discussion session

- Compare and contrast different development theories and approaches.

- We will discuss the documentary on Norman Borlaug and his fight to tackle hunger

- We will analyze why theories on the effects of geography and endowments are still supported by some.

- We will examine what is Pan-Africanism, its legacy, and the ideas of some of its proponents such as Kwame Nkrumah and Sir. Arthur Lewis.

Some questions we will review:

- How is the Green Revolution connected to the developmental theories that were promoted at the time?

- How can we evaluate the ‘success’ or ‘failure’ of this approach? Did it solve the main issue that the policy was tackling?

- Have low- and middle-income countries been able to overcome dependency?

- What is Pan-Africanism? Why is it relevant in understanding the development paths of African countries and their diaspora?

4.8 Readings Module 1

4.8.1 Required Readings Module 1

4.8.1.1 Week 2:

What is Development?

Easterly, W. (2002) The Elusive Quest for Growth. Massachussetts: MIT Press-Pp. 5-69

Sen, A.(2000) Development as Freedom. New York: Anchor Books- Introduction

Development Theories

- Adebajo, A. (2021). Pan-Africanism: From the Twin Plagues of European Locusts to Africa’s Triple Quest for Emancipation. In Adebajo, A. (ed.) Pan-African Pantheon: Prophets, Poets, and Philosophers. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Choose one of the following two readings:

Hout, W. (2016). Classical Approaches to Development: Modernisation and Dependency in Grugel, J. and Hammett, D. eds. The Palgrave Handbook of International Development, OR

Desai, V. and Potter, R. (2014) eds. The Companion to Development Studies, 3rd. ed. - Sections 2.4-2.10.

4.8.1.2 Week 3:

- Tuesday, January 17th- No in-session class. Instead, please watch: The Man who Tried to Feed the World

Poverty, Inequality, and Development

Easterly, W. (2002) The Elusive Quest for Growth. Massachussetts: MIT Press-Ch.4,5,8

Helpman, E. (2004). The Mystery of Economic Growth. Boston: Harvard University Press- Chapter 6: Inequality

Ang, Y.Y. (2016) How China Escaped the Poverty Trap?. New York: Cornell- Introduction: How did development actually happen?

4.8.2 Additional Readings and Resources Module 1

- (Highly Recommended) Podcast “Global Development Institute podcast”. In conversation: The future of development studies

- (Highly Recommended) Milanovic, B. (2014). The Haves and Have Nots-Chapter 1

- Walter Rodney: Crisis in the Periphery: Africa and the Caribbean

- Sachs, J. et al. (2004). Ending Africa’s Poverty Trap. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Vol. 1

- Duflo, T. (2012). Human values and the design of the fight against poverty. Tanner Lectures May 2012.

- Bimey, A. (2021). [Kwame Nkrumah: “A Great African but not a Great Ghanian?”]. In Adebajo, A. (ed.) Pan-African Pantheon: Prophets, Poets, and Philosophers. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Stone Roofe, A. (2021). [Arthur Lewis: Nobel Actor on a Pan-African Stage]. In Adebajo, A. (ed.) Pan-African Pantheon: Prophets, Poets, and Philosophers. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Banerjee, A. and Duflo, E. (2007). The Economic Lives of the Poor. Journal of Economic Perspectives. Vol. 21(1), 141-167

Additional Sources

- Balboni, C. et al. (2020). Why Do People Stay Poor?, Working Paper

- Chramer, C. et al. (2020), African Economic Development: Evidence, theory, policy. E-Book

- Escobar, A. (1988) Power and Visibility: Development and the Invention and Management of the Third World. Cultural Anthropology, Vol. 3(4), pp. 428-443

- Grabowski, R. et al. (2015), Economic Development: A Regional, Institutional, and Historical Approach. 2nd Ed. New York” Routledge.

- Matsuyama, K. (2008). Poverty Traps, in Durlauf, S. and Blume, L., The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics. New York: Palgrave.

Terms and Definitions

- Correlation vs. causation: Correlation refers to two variables, X and Y, that seem to be linked, but we do not necessarily know how or why. Causation happens when X causes Y. Often, we confuse the first term with the second one, which could lead to terrible mistakes.

Endogeneity: We see that X caused Y, but it may be the case that something else is at the source of X (Z), which is affecting Y.

Reverse causation: We see that X and Y are correlated, and we assume that X causes Y, but it may be that Y is (also) causing X.