Chapter 6 Module 3: Political Economy of Development

In this section of the course, we will focus our attention on different aspects that will help us understand the context of the countries and societies we study. We will explore different theories and approaches that are many times contradictory and assess them based on evidence.

Topics Covered:

- Politics and development

- The role of institutions

- Corruption and Development

- Ethnic Diversity and Fractionalization

- Conflict and development

6.1 Politics and development

Democracy is a term difficult to define. In political science, there have been candid discussions to agree on what democracy is. It is clear that democracy \(\neq\) elections, even if the term “electoral democracy” has been coined to classify countries that hold elections. Since the 1990s, most African countries hold elections, even if they are not entirely regular and if the results are many times dubious. Nevertheless, most African leaders have found on elections a way to legitimize their mandates vis-à-vis the international community (Cheeseman and Fisher, 2019).

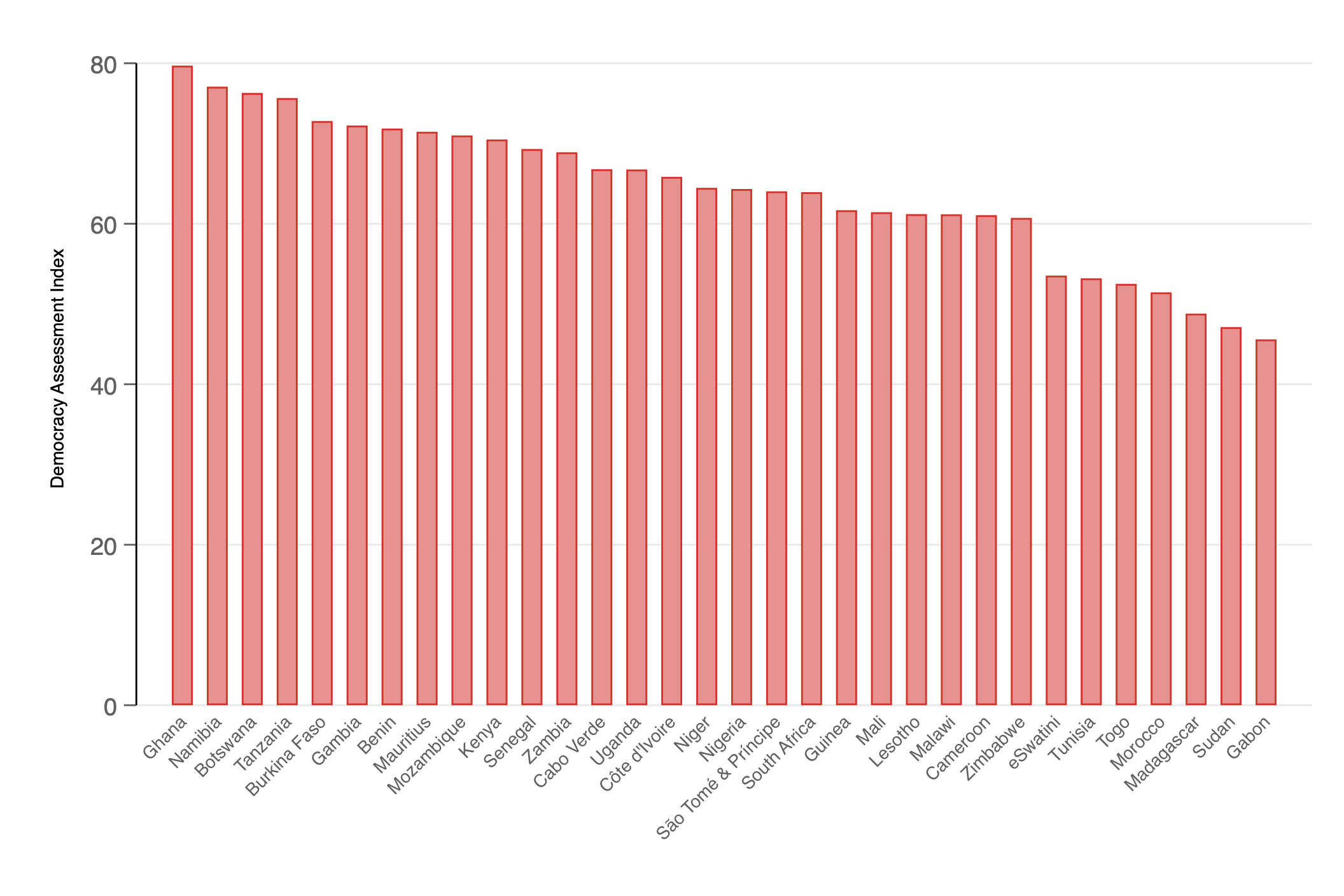

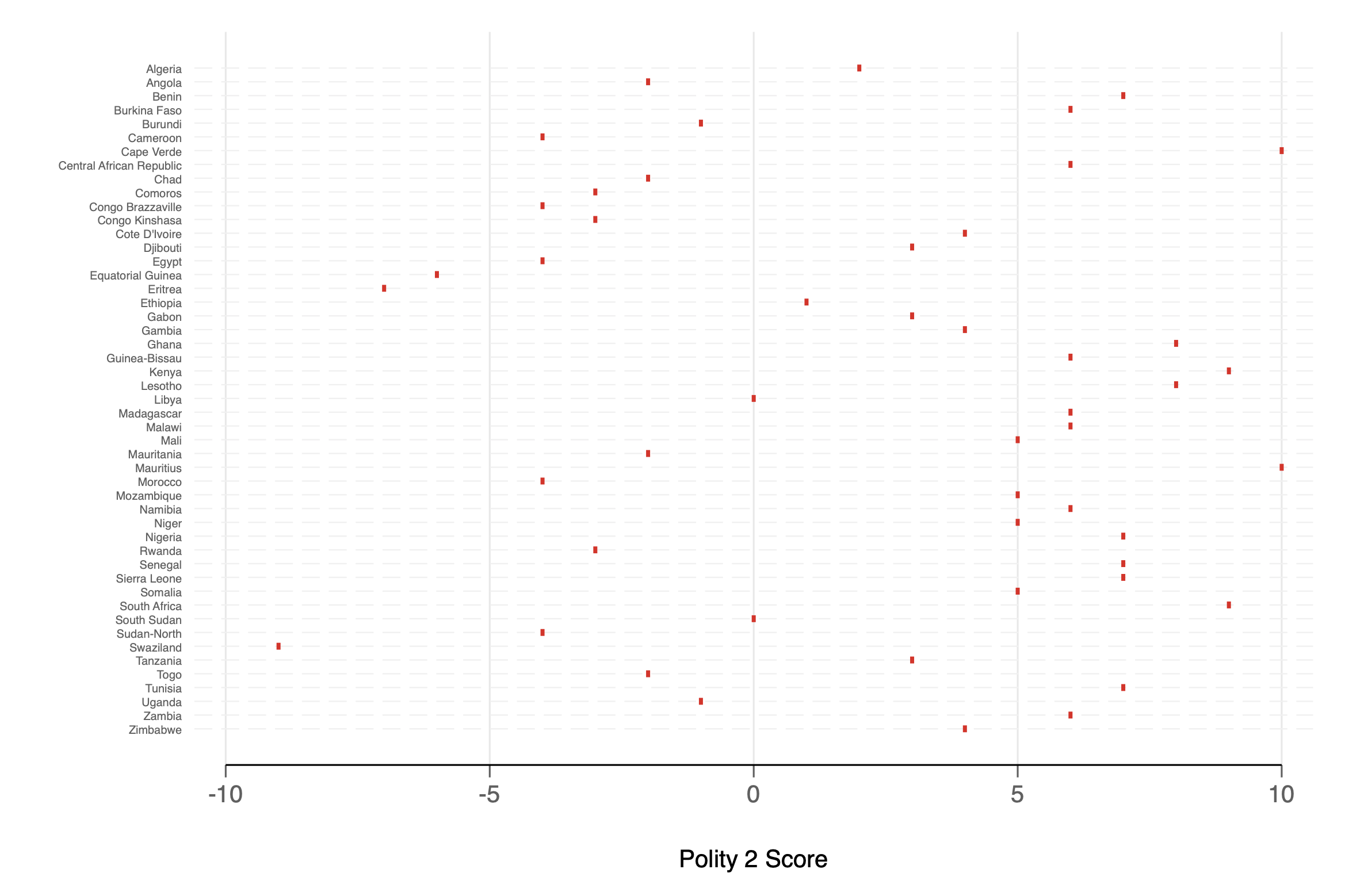

Democracy is a much broader term and, under these lenses, there is much more diversity across African governments, as shown in the Figure below, that uses data from the Center for Systemic Peace to classify countries on a scale from -10 to 10, with -10 being the most autocratic regime.

Figure 6.1: Autocracy-Democracy Index 2018: Polity 2 (Center for Systemic Peace, 2020)

Even using this scale is not enough to fully understand the spectrum of characteristics of African governments, and many times this can lead to critical issues. For instance, we must ask:

- Can democracy exist in Africa?

- What is the role of democracy in development?

- Can authoritarian regimes propel development?

To answer these questions, we first need to acknowledge that there have been many swings in the type of government regimes in Africa across time and that there are multiple realities across the continent. The following table contains some notes on the general political regime patterns in Africa. In class, we will develop these concepts further.

| Period | Context | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-colonial | Multiple tribes across the continent | Different levels of centralization. Early democracy |

| Colonial | Colonial governments | Preference to certain groups over others. “Big Men” (tribal chiefs) |

| Independence | Nationalism & Cold War | “Big Men” emerged. Unity and development as the primary concerns. Neo-patrimonial system. West vs. East competing for allies |

| 1990’s | End of Cold War | The West= political conditionality. Civil society demands. Government repression, patronage, and neo-patrimonialism. |

| 2000’s forward | China as a crucial actor | Most African countries have elections. Civil society demands. Government repression, patronage, and neo-patrimonialism. Governance. |

According to Ayittey (2006), native African institutions although different than the Western institutions, contained elements that required the population’s approval towards the king and the chiefs, with autocracy being the exception rather than the rule. This argument is supported by a recent book by David Stasavage that indicates that early democracy existed in many regions within Africa, with systems based on three motivations:

- Small-scale cooperation (remember that, because of the limited reach of the state, it was easier for members of the society to participate in councils and assemblies)

- It was a mechanism to learn what people were producing them and tax them accordingly.

- It served as a balance between how much rulers needed their ‘constituency’ and how much people could do without rulers. It was a consensual mechanism.

Although these systems had strengths and weaknesses, they showed signs of early democratic regimes. However, once colonizers arrived into these regions, they imposed a different system that, for the most part, did not adapt to the local institutions and instead imposed a system of hereditary chiefs.

This is one reason why Ayittey argues that adapting Western regimes will not work for Africa as they are artificial. Instead, he proposes to return to the African roots and heritage and build upon them. Under these native systems, consensus is preferred over a winner-takes-all system. With this, Ayittey argues that this would not entail imposing authoritarian regimes, but to impose democratic ones that are tailored to the needs of the African people, using a consensual approach. This position is similar to Nyerere’s in Tanzania.

However, there are some concerns about the application of this system, as it promotes one-party systems, with the claim that they promote stability. If the systems do not allow competition at other levels, it could become more authoritarian and prevent voices from being heard (Cheeseman and Fisher, 2020).

6.2 The Role of Institutions

Recently, we analyzed Ang’s argument on development and her criticism on the idea that history (institutions) will ‘determine’ the future of a country and society. In recent decades, institutions’ role and their importance as determinants of long-term development have received more attention. Some of the pioneers in this school of thought ar Daron Acemoglu, James Robinson and Simon Johnson (see, for instance, Acemoglu and Robinson (2012))

This has shifted the attention from arguments focused on geographic factors and the initial circumstances as drivers of development. Initially, geographic factors, on their own, were thought to be important determinants of long-term development (we talked about that earlier in the course). There is a considerable consensus in the field that this is not the case. These geographical characteristics were then argued to be associated with colonization patterns and the type of macro institutions established in certain regions.

However, as shown by Naritomi et al. (2012), it may be the case that geographic characteristics may serve to explain the local institutions that are relevant to explain intra-country differences and local patterns of development. The authors use Brazil’s case, a large country for which geography (distance to the equator) seems to explain the differences in income per capita. The authors use the resource booms that took place during the colonization period: sugar and gold and explore the types of institutions established in the country in geographical areas where these resources could be produced or extracted. The authors find that sugar production led to the unequal distribution of land whose effects remain nowadays. Municipalities whose origins are associated with gold production have worse governance practices.

These effects are similar to the results found by Dell (2010) in Peru, where a forced labor mining system in Peru (“Mita system”) implemented by the Spaniard colonizers between 1573 and 1812 is correlated with a contemporary lower consumption (of 25%) and prevalence of stunted growth in children (by 6%).

These results show that the channel throughout which geography may impact development is through its impact on the established institutions. In turn, historical institutions play a role in determining property rights enforcement, ethnic fractionalization, inequality, and public goods provision.

How do they impact development? What type of institutions are we referring to? When we talk about the effect of institutions on development, we will primarily look at the effects of governance, or state capacity. These are not the only institutions that matter for development, as other ones are also worth analyzing, such as property rights, strong judiciary, and financial institutions (an independent central bank, for instance).

According to Englebert (2000), the clash between pre- and post-colonial institutions may have had a strong effect on Africa’s development path. When looking at the mechanisms, Englebert argues that whenever there is a clash between institutions inherited from colonialism and pre-colonial institutions, institutions will be seen as less legitimate and will lead to a system closer to neo-patrimonialism. When these institutions are more compatible, the new institutions will seem less artificial and considered more legitimate by the local population. The state will be stronger and economic development will pursue. In this case, then, how institutions impact development in Africa is throughout the legitimacy (vertical and horizontal), they have among the population. When the state’s configuration does not seem legitimate, political elites will resort to neo-patrimonial policies and will invest little in improving governance and promoting the development of the territory.

In the meantime, Herbst (2000) argues that state capacity building depends on three aspects: the cost of increasing state capacity, the nature of the country’s boundaries (the territorial boundaries that were artificially set by the colonizers and that also serve as buffers of other institutions), and the design of state systems. Effectively, if the cost is higher than the benefit, no state capacity will be created. In that sense, Herbst concludes that African institutions reflect the environment and the historical forces and that the way leaders meet the challenges set by this context will determine the viability of strong African states.

The Role of Geography on Development

There are different theories that have been suggested to explain the motivations behind economic growth. In general, we can identify three:

- The Geography/Endowment Hypothesis: This theory posits that the environment has a direct effect on the quantity and quality of labor, land and production technologies. This, in turn will affect the type of economic development a country has.

- The Institution Hypothesis: This theory states that any effect that the environment has on economic growth comes from the its effect on the institutions that are established in a region.

- The Policy Hypothesis: This hypothesis holds that economic policies and institutions are just a reflection of the current state of the world, with history and historical institutions playing a very small role in economic development, as policies can be quickly reversed.

6.3 Corruption and Development

There is a widespread idea that corruption work in detriment of development. When we think about corruption, we closely link it to violence and the perpetuation of poverty and underdevelopment. The direction of this relationship is not entirely clear. After all, is it the case that poverty and underdevelopment are the cause of corruption and violence? Or is it the other way around: violence and corruption as endemic causes of poverty?

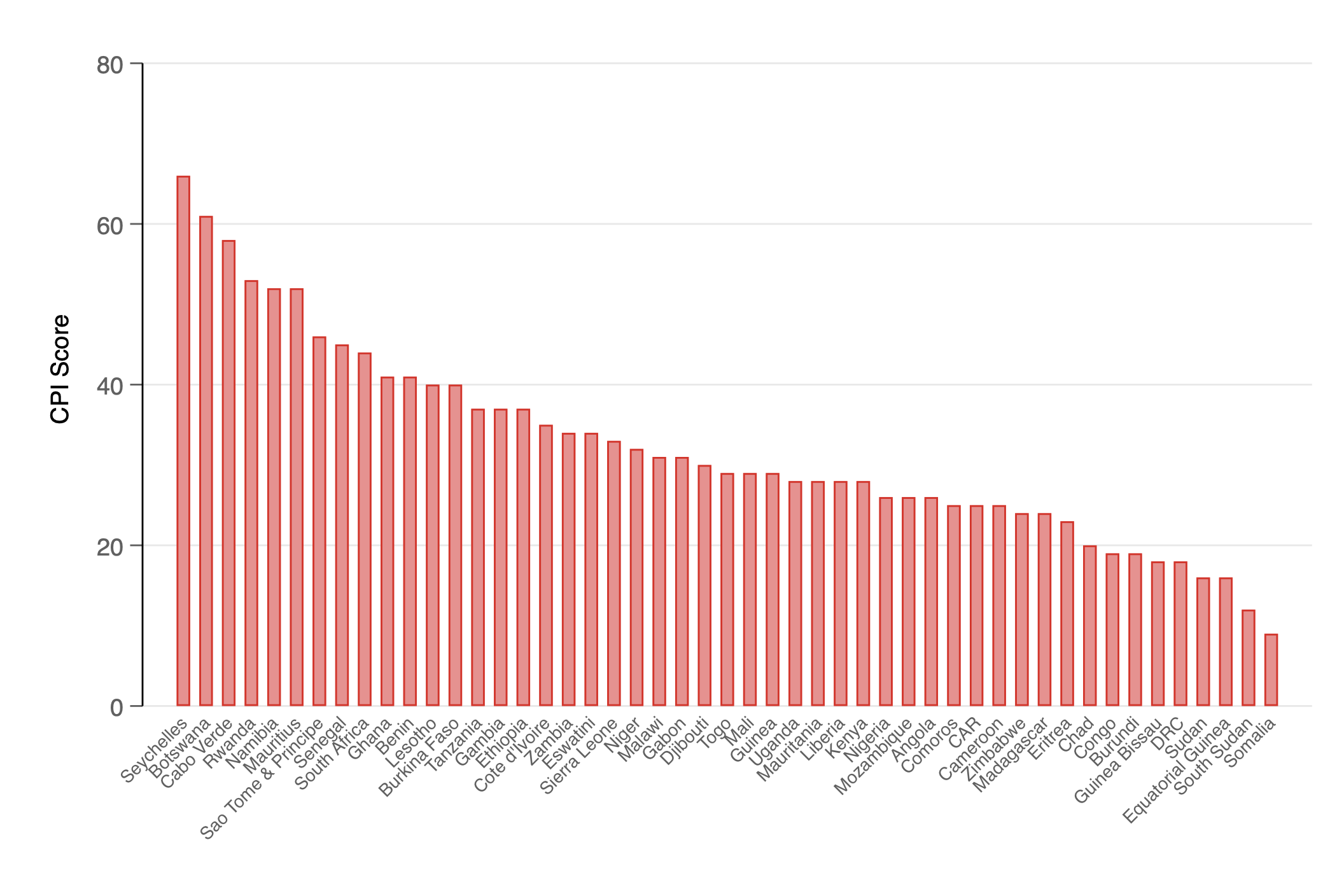

Although no clear and definite answer exists to this conundrum, many have explore the relationship between these two factors that seem closely linked. The graph below shows the Corruption Perception Index of 2019 for African countries. The index gives a score between 0 to 100 to countries, with 100 being the least corrupt country. It is clear from the graph that those countries with the lowest indices (more corrupt) also show the lowest levels of income per capita.

Figure 6.4: Corruption Perception Index. Transparency International (2020)

Although the average score of the region is 32/100, there is some variation among the results, with eight countries having a score below 20 and 6 countries scoring higher than 50 in the index. But this index may not say much without some evidence on how it takes place.

Yet, recent evidence argues against these claims. As Ang (2020) argues, both China and the United States have used corruption as a tool to promote economic growth.

Nevertheless, the situation has been different for most low- and middle-income countries. Fisman and Miguel (2008) have explored the relationship between corruption, violence, and development with the goal of proposing evidence-based solutions that tackle some of the incentives behind corruption.

Titeca and Thamani (2018) provide some evidence for the DRC case, a country that has persistently shown high levels of corruption. The authors show how corrupt cabinet ministers channeled resources to president Joseph Kabila to keep their positions and avoid being prosecuted for receiving payments from business people and other politicians at lower levels. This expands the concept of neo-patrimonialism to show that it travels in both directions: from top to bottom, but also from the bottom to the highest levels.

Corruption also occurs in the form of rent capture and the spread of political elites’ presence into the economic sector. Evidence on how this works exists across the region, with government members showing vested interests in enterprises.

However, international actors have also been essential players in this corruption network. A large number of corruption scandals have involved multinational companies that pay bribes, international banks, and even international governments (tax havens that keep high levels of secrecy). Corruption in the aid sector is also prevalent, and this may put many developmental and humanitarian programs at risk.

At the local level, the population participates, voluntarily or not, in the process of bribery and corruption. In this case, although women participate to a lower degree in these practices (Transparency International 2019), they are also more vulnerable to cases of extortion for the provision of basic services (Transparency International, 2019).

6.4 Ethnic Identity and Fractionalization

Identity has always been a crucial aspect defining economic outcomes. We see that not only in low- and middle-income countries, but it defines local relationships as well as international interactions. While we may praise and value the existence of multiple perspectives, it is well known that some identities have historically been overrepresented while others have been excluded.

One of the most salient aspects of our identity is our race. In the development field, the focus has been on how ethnic diversity affects the implementation of different policies.

Habyarimana et al. (2007) show this, identifying potential mechanims that link ethnic diversity to the underprovision of public goods. First, in homogeneous communities people tend to have a stronger preference to redistribute public goods. Second, in homogeneous regions social networks are stronger and it is easier to ‘punish’ those that prefer to redistribute less.

Furthermore, the effects of these policies may lead to inequality that varies across different groups, which may in turn hurt economic development. The seminal paper by Alesina, Michalopoulos and Papaioannou (2012) shows that ethnic inequality as the result of different policies leads to underdevelopment. This is, areas with more ethnic fractionalization have lower provision of public goods, which in turns affect the prosperity of the population.

Yet, the links between ethnic diversity and conflict are contested. Although Fearon (2003) argues that ethnic fractionalization is a strong predictor of conflict, other authors do not agree with this assessment. For instance, Blattman (2022) argues that even if ethnic fractionalization may be a common element in many conflicts it is not a sufficient element (and possibly not a necessary one) to spark violence.

6.5 Conflict and development

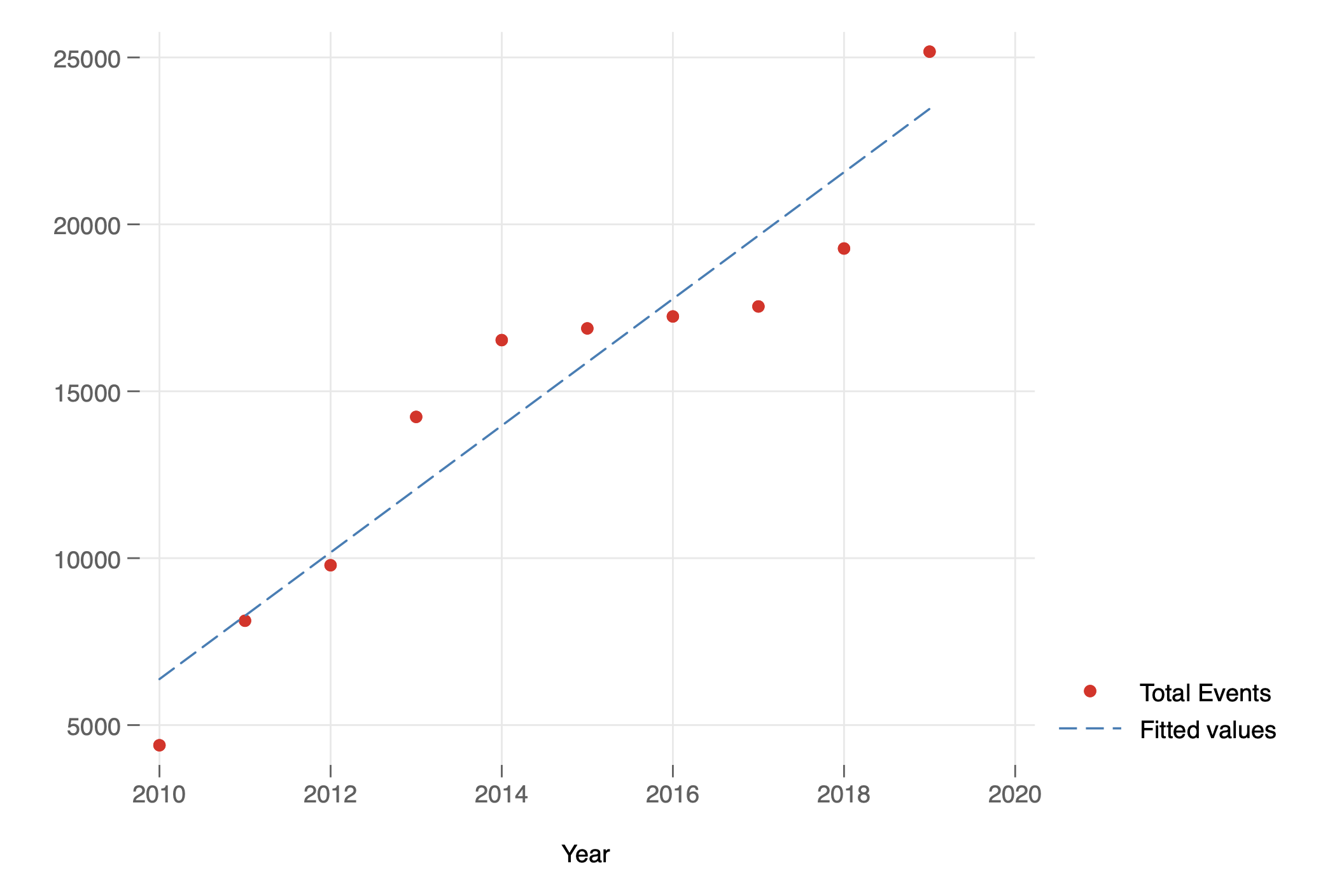

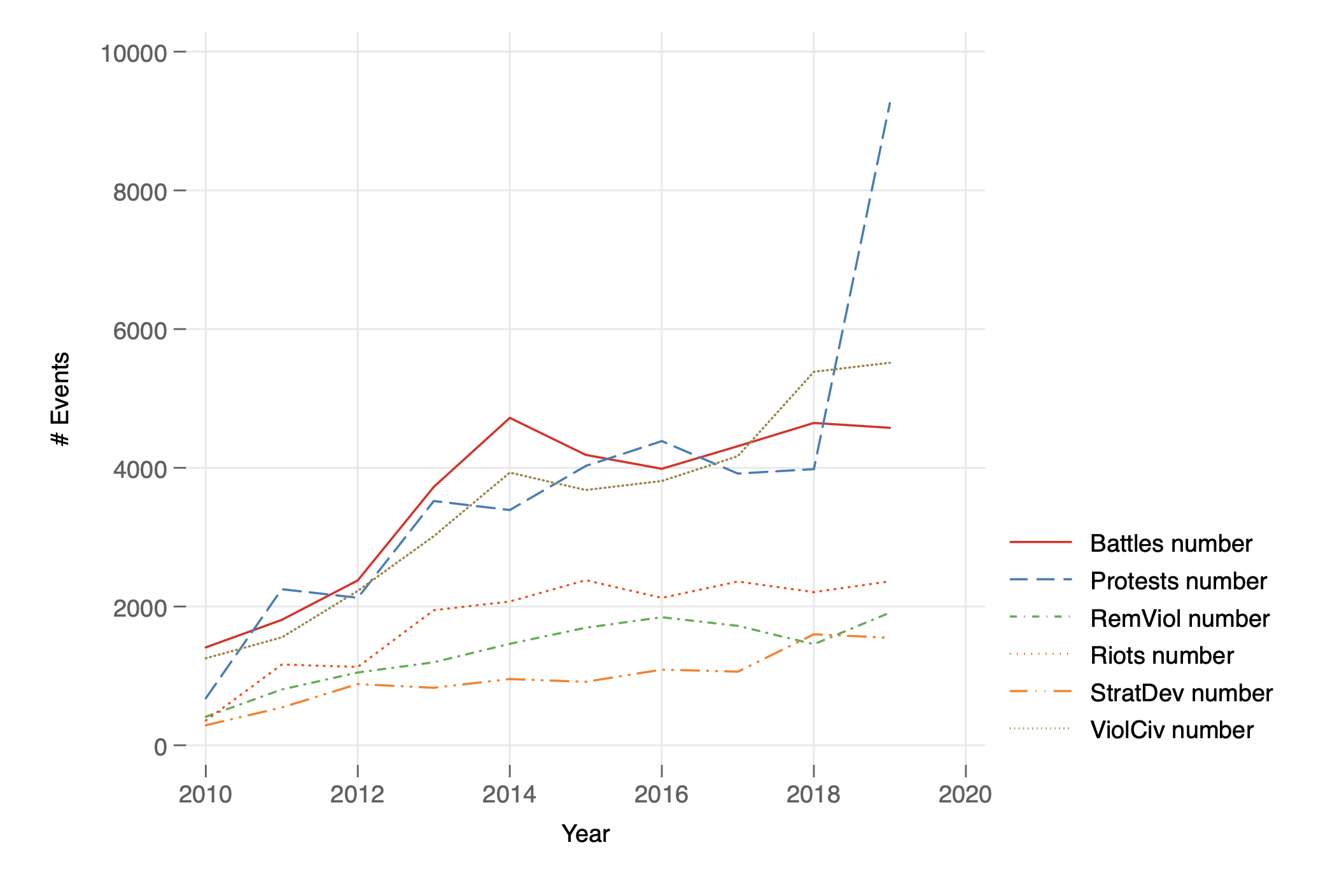

After the Cold War, there was a shift in the type of conflicts across the globe. In Sub-Saharan Africa, there has been an abundance of civil conflict. The following chart shows the evolution of conflict across time, and the predicted pattern of conflict, with a positive trend indicating the increase of conflict events.

Figure 6.5: Conflict Trend 2010-2019. ACLED (2020)

However, the configuration of conflict has changed, with protests becoming mainly the primary source of conflict in the region. Still, battles (civil conflict) remains high.

Figure 6.6: Conflict Trend 2010-2019. ACLED (2020)

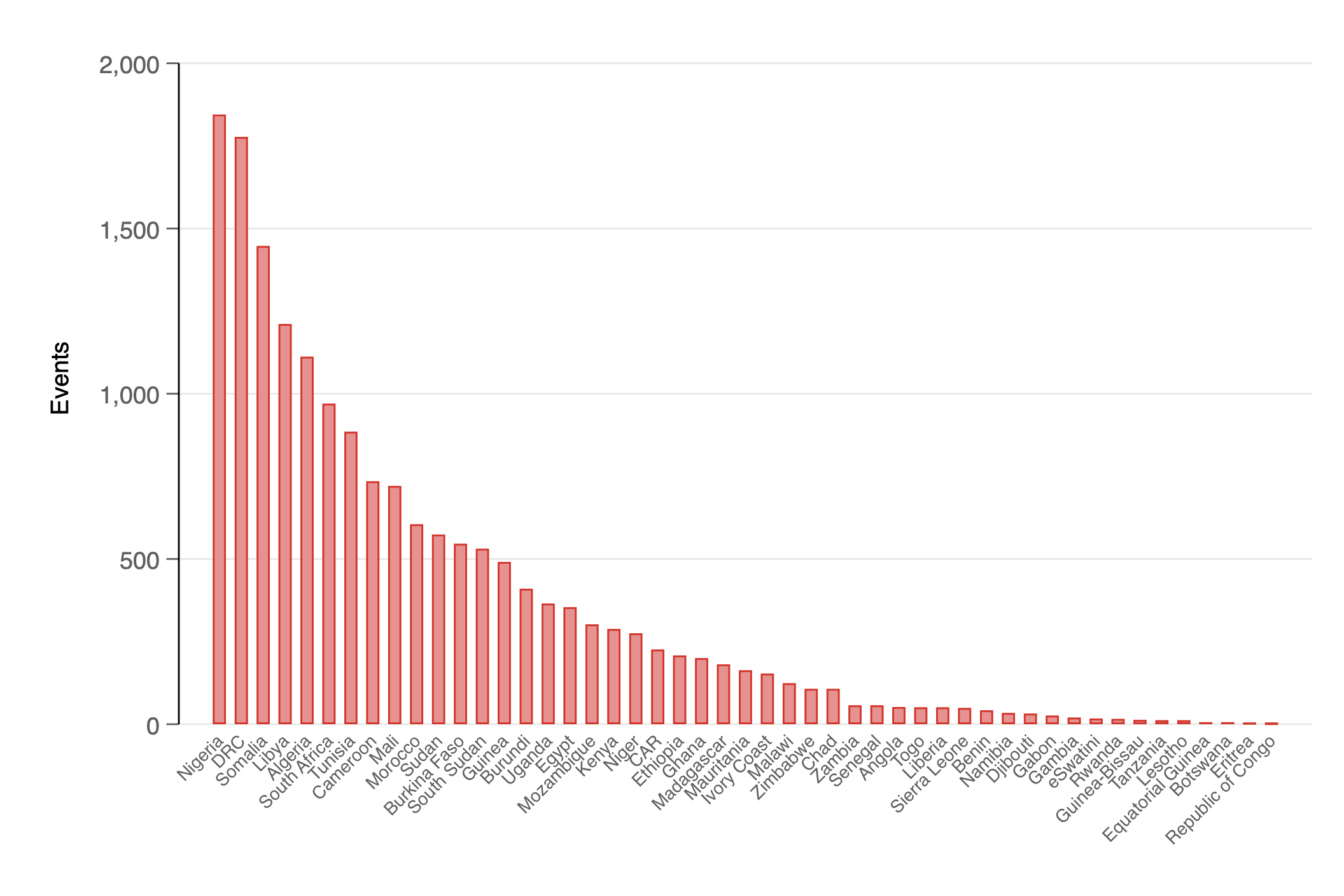

Conflict is not equally persistent across the continent, with most of the violence concentrated in some states. The following graph shows the distribution of conflict events between January and July 2020 across African countries. In the seven months, two countries had more than 1,5000 conflict event10.

Figure 6.7: Conflict Trend 2010-2019. ACLED (2020)

What causes this substantial persistence of conflict? How is this related to development? There are different theories on this subject.

It has been argued that civil war is related, at least in part, to the presence of natural resources. In Africa, Angola, DRC, Sierra Leone, Liberia, and Sudan are the primary examples. However, finding a pattern of causality is hard. For instance, as Ross (2004) argues, there might be other elements that are related to conflict that may lead to a country to highly depend on its natural resources, leading to a spurious relationship. Still, he does a literature review and finds that oil exports are related to civil war, whereas resources that can be looted are correlated with the duration of conflict. Why would that be? One answer might be because controlling resources give access to economic gain. Different groups assess their probability to control these resources and the potential costs. These costs depend on different factors, such as the characteristics of the terrain, the reach of the state, among others (See, for instance, Fearon and Laitin (2003)). Sanchez de la Sierra (2020) argues that, for the DRC’s case, minerals that cannot be concealed lead to the establishment of warlords (‘stationary bandits’) that tax and protect the mines. Contrary to this, the presence of minerals easy to conceal leads to stationary bandits in the villages, leading to the establishment of sophisticated fiscal and legal administrations to extract revenue. Although accessing minerals as a source of wealth is the goal of these warlords, they provide some of the functions that the state does not provide in these areas.

Also, ethnic diversity may provide a ‘motivation’ for conflict, as it may work as a source of grievance, although the evidence is mixed. For instance, Esteban, Mayoral, and Ray (2012) empirically test if polarization, fractionalization, and ethnic differences influence conflict in 138 countries throughout 1960–2008. They find that countries in the top 20% of ethnic polarization in the sample have a probability of conflict of 29%. In contrast, countries in the bottom 20% show a 13% of conflict, after taking into account (controlling for) other factors that are also important to explain conflict. These findings are supported by those of Montalvo and Reynal-Querol (2005).

Chabal and Daloz (1999) expand the argument of violence in Africa to include it as a political tool used by the elites to control the population. The authors normalize violence and state that it is used by the elites to control the system. Although the book was criticized by missing empirical understanding, it did provide a good notion of how everything that happens inside the system may be calculated and used as a political tool to link the formal and informal economy and politics worlds. This includes civil war, which, although not seen as desirable, may be understood, according to the authors, as unavoidable to bring necessary change.

How could civil war and violence affect development? Although this question may require a full session, we can certainly touch on different elements, and we will further discuss them in class. Of course, the main effects are related to the devastation and the loss of lives and infrastructure, that translate in low economic growth and poor development among the population. Nevertheless, the effects go much beyond that. Conflict leads to a lack of trust, leading to a sense of continuous tension. It also makes state-building harder, from the material perspective, but also because state weakness was at the source of conflict. However, there are cases in which the reconstruction process has worked. The most evident case possibly is Rwanda after the 1994 genocide. However, South Africa could also be included, among others11.

Nevertheless, conflict does not only affect countries that struggle with it. As shown by Adhvaryu et al. (2018), countries that have resource-rich neighbors tend to have lower economic outcomes, as the neighbors have a higher probability of being involved in a conflict.

Still, Aili Mari Tripp (2015) indicates that post-conflict states in Africa have also been able to move forward. She specifically argues that women have played a crucial role in the reconstruction of African countries at the outset of conflict and that a by-product of war in countries around the continent has been a higher political leadership rate for women.

6.6 Seminar Questions Module 3

6.6.0.1 Week 6:

- Politics and Institutions

- What are some of the political and institutional elements that can help us understand the development path of a country? Is democracy necessary for development?

Please ensure that you explore how and what institutions are relevant for economic development.

6.6.0.2 Week 7:

- Factors behind conflict and endemic poverty

- How are corruption and ethnic fractionalization affect economic development?

- Conflict and development

- Is the presence of violence and conflict a more valid measure of prosperity? What are some of the factors behind it?

6.7 Activities Module 3

- We will examine our own positions about corruption: What would you do?

- We will discuss about what is democracy

- A challenge on ‘Institutions and Development’

6.8 Readings Module 3

6.8.1 Required Readings Module 3

6.8.1.1 Week 6:

Politics and development

Ayittey, G. (2006). Indigenous African Institutions, New York: Transnational Publishers. Read the Introduction

Please watch: Rocking your Priors Podcast with Dr. Alice Evans “The Decline & Rise of Democracy”: Professor David Stasavage. You can listen to the Podcast instead.

The role of institutions

- Podcast: - Rocking your Priors Podcast with Dr. Alice Evans “The Narrow Worridor”: Professor Daron Acemoglu.

6.8.1.2 Week 7:

Corruption and Development

Ang,Y (2020). China’s Gilded Age: The Paradox of Economic Boom and Vast Corruption. Chapter 2

Fisman, R. and Miguel, T. (2010). Economic Gangsters Corruption, Violence, and the Poverty of Nations Chapters 2, 3, 4.

Svensson, J. (2005). “Eight Questions about Corruption”. Journal of Economic Perspectives. Vol. 19 (3). Pp. 19-42

Ethnic Fractionalization

- Easterly, W. (2002). The Elusive Quest of Growth Chapter 13.

6.8.1.3 Week 8:

Conflict and development

Podcast: From Street Fights to World Wars: What Gang Violence can Teach Us About Conflict

Collier, P. (2007). The Bottom Billion : Why the Poorest Countries Are Failing and What Can Be Done About It Chapter 2.

Ross, M. (2004). “What Do We Know about Natural Resources and Civil War?”, Journal of Peace Research, Vol. 41(3). pp. 337-356

6.8.2 Additional Readings and Resources Module 3

Conflict and Development

- Walter, B. (2015). “Why Bad Governance Leads to Repeat Civil War”. Journal of Conflict Resolution. 59 (7) 1242-1272

- Sawyer, A. (2004) “Violent con£icts and governance challenges inWest Africa: the case of the Mano River basin area”. Journal of Modern African Studies 42(3). pp. 437-463

- Moss, T. and Resnick, D. (2018). African Development, 3rd. Ed. Boulder: Kynne Rienner- Chapter 5

The role of institutions

- Englebert, P. (2000) “Pre-Colonial Institutions, Post-Colonial States, and Economic Development in Tropical Africa”. Political Research Quarterly. Vol. 53(1). pp: 7-36

- Herbst, J. (2000). “The Challenge of State-Building in Africa”. In Comparative Lessons in Authority and Control. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Ethnic Fractionalization

- Kasara, K. (2007). “Tax Me If You Can: Ethnic Geography, Democracy, and the Taxation of Agriculture in Africa”. American Political Science Review. Vol 101(1). Pp. 159-172

- Alesina, A. et al (2012). “Ethnic Inequality”. NBER Working Paper Series Working Paper 18512

- Habyarimana, J. et al. (2007). “Why Does Ethnic Diversity Undermine Public Goods Provision?”. American Political Science Review. Vol. 101(4).

Additional Sources

- Cheeseman, N. and Fisher, J. (2019). Authoritarian Africa. New York: Oxford University Press

- Lipset, S. (1959), “Some Social Requisites of Democracy: Economic Development and Political Legitimacy”, The American Political Science Review, Vol. 53(1), pp. 69-105

- Przeworski, A. Alvarez, M., Cheibub, J-A. and Limongi, F. (2000). Democracy and development. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.