Chapter 5 Module 2: The Context

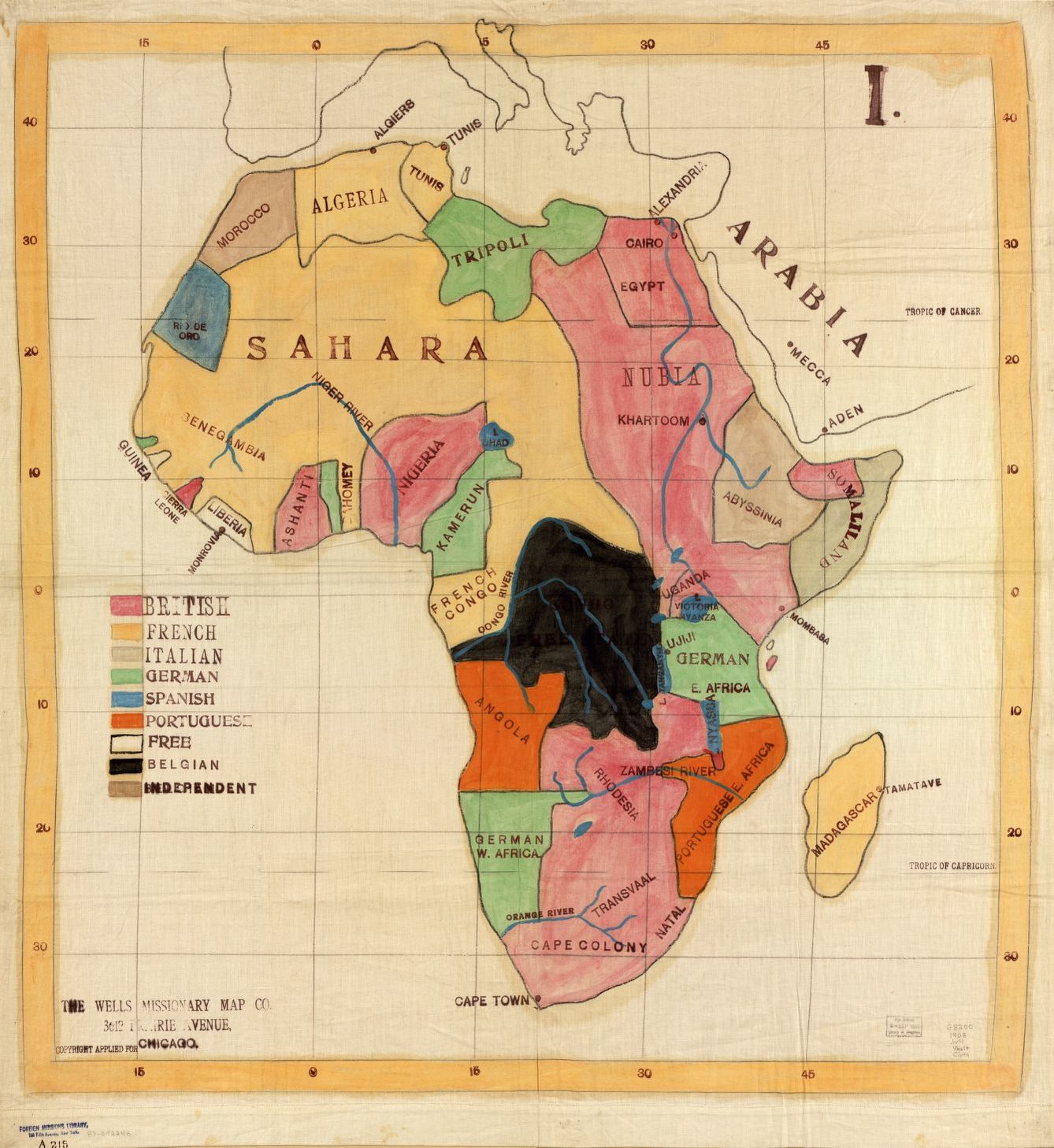

Figure 5.1: Source: Library of Congress, (1908)

In this section of the course, we will do a deeper analysis on how different moments in history have affected the development path of low- and middle-income countries, particularly in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Topics Covered:

- Pre-colonial period and trade of enslaved persons;

- The Legacies of Colonialism

- Development policies after Independence

- The Washington Consensus and Structural Adjustment policies

5.1 Pre-colonial Africa

The first topic that we will analyze in this section is the role of history for development. Up to what extent does history influence the development path of a society? This interdisciplinary analysis field is quite recent, but it has been prolific, so we will explore how different historical events have affected development in Africa and beyond.

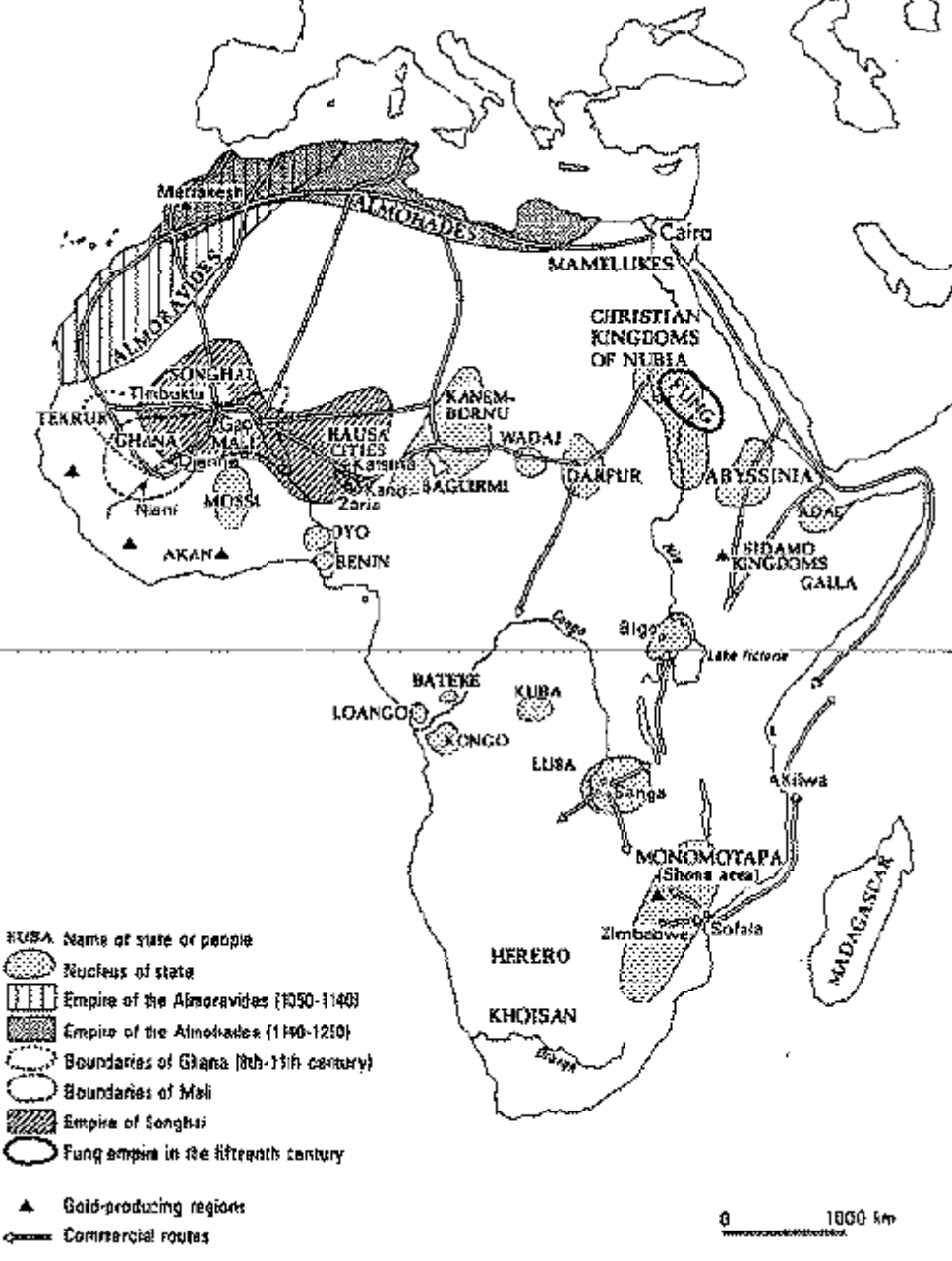

Before colonization, Africa had a very different configuration than the one we see today. A large share of the continent was unoccupied, and the population was widespread. The Bantu family of languages corresponds to the languages spoken in the Niger-Congo region, and it comprehends about 450 languages, which spread and evolved across the continent.

Contrary to what we see in western societies, African groups were hardly centralized and did not have strict hierarchies. People tended to live in smaller groups and did not recognize a robust central authority (Cheeseman and Fisher, 2020). Just a few groups, such as the Kingdom of Ashanti, in what is now Ghana, the Lozi Kingdom in what is nowadays Zambia and the Zulu Kingdom in Southern Africa, had a more complex and centralized political system.

Figure 5.2: Pre-Colonial States in Africa. Ayittey, (2006)

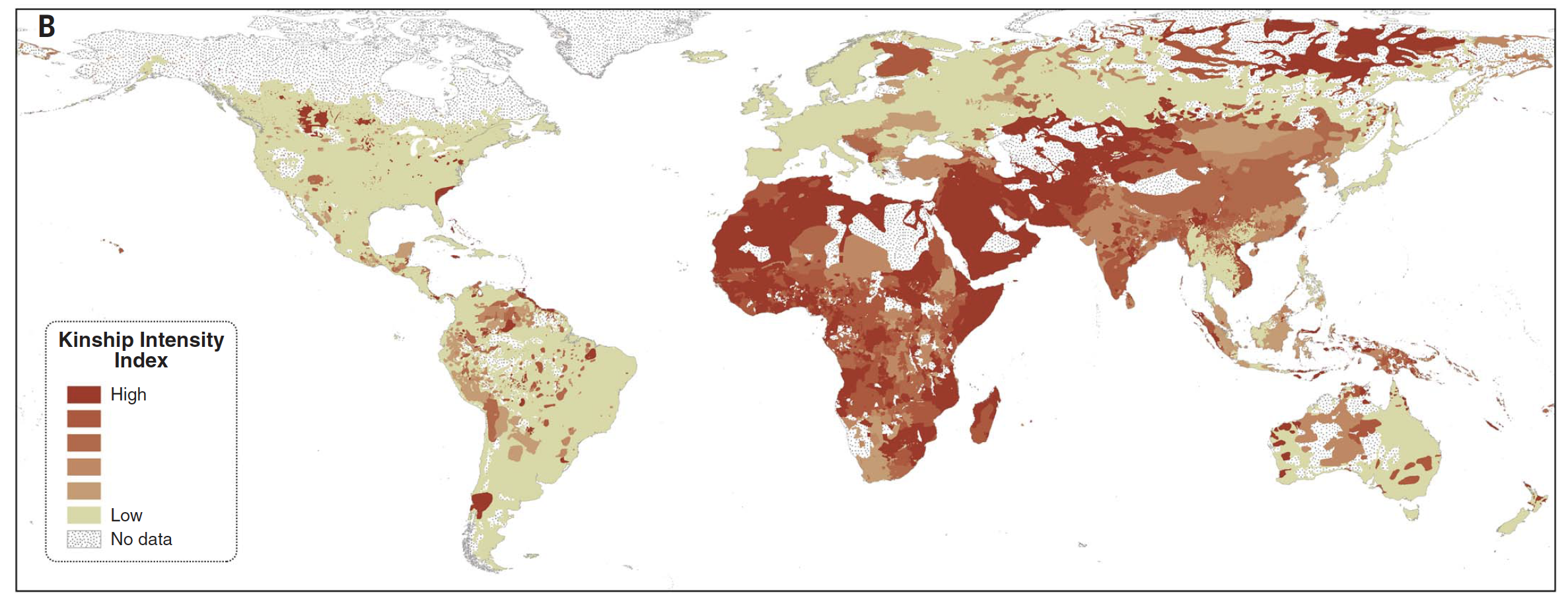

Still, even if many of these groups were not strictly hierarchical, African peoples were characterized by intensive kinship norms 7. According to Shulz et al. (2019) this element has affected the relationship with the family unit and may affect more extensive cooperation.

Herbst (2000) argues that although the territorial boundaries in pre-colonial Africa were not set in the same way as European boundaries, it does not mean that the state did not exist. However, since mapping was not available, it was hard for states to control large areas of land, so the state’s reach was more limited. Shillington (2019) states that, in the 16th century, more specialization and population growth led to the development of larger political units and an increase in power of certain groups. Some examples of that are the Luba, Lunda, and the Kongo Kingdoms, in Central Africa. These Kingdoms, as well as others in Black Africa would rely on taxes and customs, as well as gold mining where available to support their systems. Many also relied on booties from foreign expeditions. In return, these Kingdoms had a complex judiciary and military system (Anta Diop, 1987),

At the same time, Arab influence was quite relevant in different parts of the continent. Trading networks started to expand, creating the Swahili Arab trade networks, which included goods such as gold, ivory and furs. At the end of the fifteen century, the Portuguese expected to get access to Indian goods from the south, bypassing the Muslim control. When arriving to the African continent, they found the wealth that existed and decoded to seize control of it too by the use of force. They erected a fort named Fort Jesus in Mombasa around 1599, which became the source of authority and violence that the Portuguese kept in the country during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries (Shillington, 2019, pp. 168).

5.2 The Trade of Enslaved Persons

Contrary to what happened in Europe, internal warfare did not lead to the control of more land. Rather, it translated to the control of other humans, which were then traded. Within this context, states were dynamic and fluid, with outlying territories separating from the center.

Figure 5.3: Kinship intensity index. Schulz et al., (2019)

Enslaved persons existed in Africa way before the arrival of the Europeans. However, it is important to differentiate the treatment and social status of these groups of the population before and after the Europeans arrival. Anta Diop (1987) states that, before the arrival of the Europeans, enslaved persons (mostly war prisoners) could become part of the family (particularly in the case of the slave of the mother’s household). In Muslim north Africa, some male slaves rose to high office, whereas women slaves usually became concubines.

With the arrival of the Europeans, the extent in which the trade of enslaved persons changed and led to a reconfiguration of the continent, and of the whole world. Since the 15th Century, different kingdoms, including the Ashanti, had contact with European traders, with whom they traded gold, ivory, and enslaved persons. This argument goes against the traditional argument on the Triangular slave trade that argues that. In contrast, Europe provided manufactured goods (such as guns), Africa ‘just’ provided enslaved people transported to the Americas for the production of commodities that were then transported to Europe. Africa was also the source of other goods valued by the Europeans.

The slave trade did have detrimental effects on Africa’s economic, social, and political development. One of the first and significant studies in this regard is Nunn (2008), who shows that countries that were the source of most of the enslaved persons between 1400 and 1900 are the poorest in Africa nowadays. This finding is quite robust to different specifications, and Nunn shows that, in fact, at the point at which this practice took place, the source of these persons were wealthier than other areas. This indicates that it is not the fact that these areas never developed, but that the slave trade had a detrimental effect on these peoples. These findings are relevant, as Nunn explains that 72% of the income gap that currently exists between Africa and the rest of the world would not exist, had the Atlantic slave trade never happened.

Other authors, such as Green (2013), Whatley and Gillezeau (2011), and Whatley (2014), show that the slave trade caused ethnic fractionalization, and lower institutional quality in locations closer to the ports of shipment. Zhang and Kibriya (2016) show the higher prevalence of conflict in areas with a more significant slave trade intensity. These outcomes may explain some of the mechanisms behind the poor economic, political, and social conditions in many African regions.

An additional effect of the slave trade was the arousal of polygamy, and this may also seem to have contemporary effects for the livelihoods of African peoples. This is because in polygamous relationships, women are more likely to have sexual partners than their husbands, which has led to an increase in HIV rates in these areas, as Bertocchi and Dimico (2015) show.

What caused the trade of enslaved persons?

Shillington (2019) argues that, at its origins, African perceptions of identity were based on ethnicities and African nations. As a result, when Europeans arrived in West Africa, they were seen as trading partners, whereas some African nations were seen as dangerous enemies. This hostility led to an increase in warfare among African nations and war captives becoming slaves, that were then traded with the Europeans. This activity became more widespread as guns became available in the eighteenth century and as demand for enslaved persons was rising.

Although many structural factors have not been examined yet, some research has shown that abnormally cold years led to an increase in the trade of enslaved persons (Fenske and Kala, 2015) and that uneven terrain could escape the slave trade (Nunn and Puga, 2015). Besides, Fenske and Kala (2016) show that the abolition of the slave trade by the English in 1807. However, it indeed reduced the trade of enslaved persons; it also increased violence and coercion within the region. This indicates that the way the trade of enslaved persons happened led to a reconfiguration of the region that had lasting effects and that abolishing this practice also generated detrimental effects.

What led to the end of the Atlantic trade of enslaved persons?

Different elements contributed to the abolition of the slave trade. Anti-slave trade campaigns in Britain, the prohibition of the institution of slavery in Northern U.S. states (and the work of the Quakers in that regard), as well as the revolutionary government in France were some of the motivations in the West. But, more importantly was also the emancipation of second-generation slaves in the colonies, starting with the Haitian Revolution.

Still, there is much debate as to what are the clear causes for the abolition of slave trade, and whether the causes were primarily economic or humanitarian. The economic argument indicates that the expansion in Caribbean sugar plantations in the late eighteenth century led to an overproduction of sugar (and to the fall of sugar prices), whereas production costs remained high (including the price per enslaved person). This led to a loss of profit, and to bankruptcy of some as plantation owners could not pay their debts to European bankers. This made investment in manufacturing at home more appealing (this was at the time of Industrial Revolution), including hiring wage labor, as these free workers could also become consumers (Williams, E., 1944).

The humanitarian cause criticizes the economic argument by arguing that the abolition of slave trade was detrimental for the economy of those countries that practiced, and therefore the causes were purely humanitarian (Drescher, E. 2010).

5.3 Colonization and Development

As we see in the case of the trade of enslaved persons, African peoples fought against colonization, just as it happened in Latin America. The relationship was more complicated than what Western history textbooks acknowledge.

With the arrival of the Portuguese, there were multiple attempts to increase the European influence in the continent. In large degree, these attempts came from Roman Catholic Christian missionaries from Portugal. Still, at least until the early eighteenth century, European Christianity had virtually no effect on the peoples in Sub-Saharan Africa. This changed in the early nineteenth century, as Christian missions spread throughout the region. Particularly, Sierra Leone, South Africa and Liberia became early fields of success for these missions, as interior regions were much harder to access. Still, these missions were key in shaping the advent of European colonialism, using their influence to promote European expansion or by directly deceiving the local chiefs (Shillington, 2019).

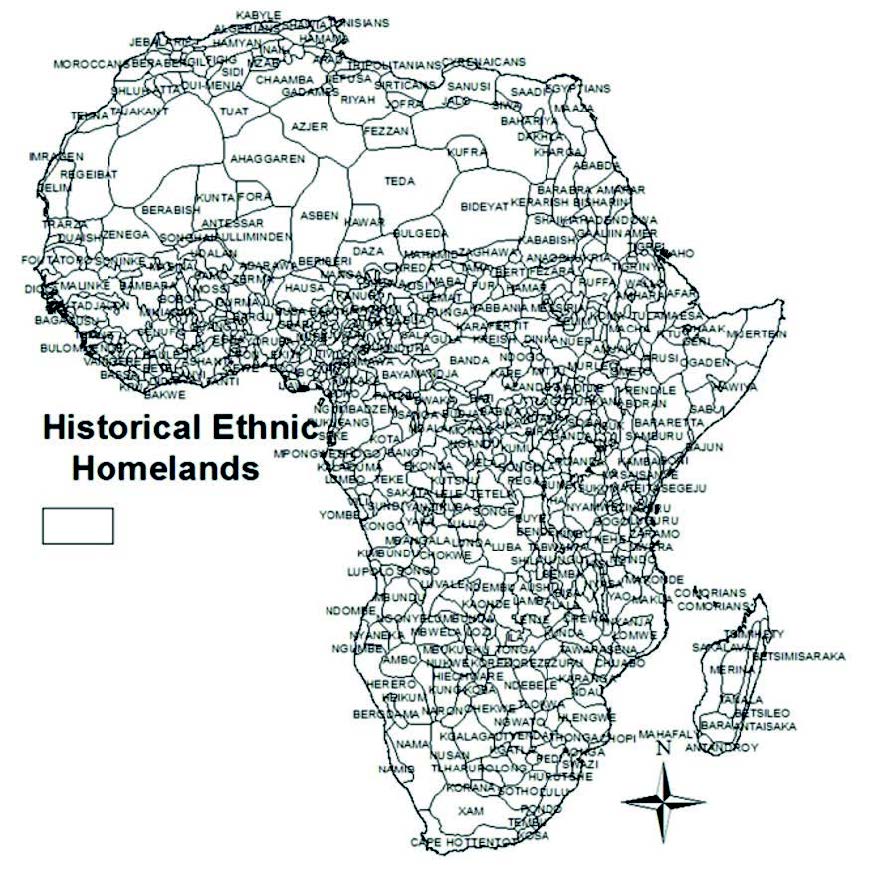

Between the mid-1800s and 1900, the ‘Scramble for Africa’ took place, with European powers signing treaties and deliberately dividing the African continent, without further knowledge of the terrain or the peoples that occupied that land. This had effects on the further development of the continent. As argued by Michalopoulos and Papaioannou (2016), the division of the continent led to the fragmentation of ethnic groups. This, in turn, led to ethnic discrimination, inequality, and conflict.

Figure 5.4: Ethnic Groups in Africa. Michalopoulos and Papaioannou (2016)

In addition to this, the partition of Africa led to the creation of multiple landlocked countries. In the continent, out of the 49 countries, 16 are landlocked. Why is this an issue? Well, landlocked countries face higher transportation costs than countries that are next to the coast. Besides, these countries largely depend on the conditions of their neighbors to trade. For instance, if a neighboring country faces political upheavals or civil war, international trade can be even more challenging, if not impossible.

During colonization, European settlers were based in areas closer to the coast or in clearly delimited areas with a more favorable climate. From here, roads and railways were built towards areas where the natural resources were located. These cities played an essential role as the entry point of European settlers and the place where exports and imports took place. This is why most of the capitals of African countries are located on the coast (Cheeseman and Fisher, 2019).

However, the fact that Europeans were established in particular areas meant that they only invested in infrastructure development in these areas. To control the rest of the territory, they relied on traditional leaders that were co-opted and forced to keep control of these areas, further increasing the inequality among different tribes and setting the ground for future conflict, for the emergence of ‘Big-men’ after independence, and neo-patrimonialism.

Even with the assistance of traditional chiefs, the Scramble of Africa created huge countries, with territories that were vast and hard to penetrate. This limited the reach of the state and prevented it to ‘monopolize violence.’ This, in turn, has prevented the emergence of state capacity and limited the development of multiple regions.

Although there is a wide range of variation among the colonizers, all the systems were characterized by the brutality of the methods used to keep the population under control. In some cases where cash crops were produced (notably in British colonies), Africans were able to use these as a way to compete against the Europeans and promote their development (Austin, 2014)

A seminal paper, Acemoglu, Robinson and Johnson (2001) shows that colonization impacted every region involved. For the colonizers, it led to the development of some European countries, while it reduced growth in others. However, the main impact happened in the colonized regions. In this case, the effects depended on the initial conditions of the countries.

The authors’ central argument (which has been controversial, to say the least) is that the disease environment faced by the Europeans mattered a lot to the type of institutions set in the colonies. In areas where Europeans had a lower chance of surviving, they would create extractive institutions, that could allow the colonizers to extract resources at a higher pace. In cases with lower risks for the settlers, the type of institutions would lead to a more comprehensive state. These institutions have had persistent effects and could explain variations in development across colonized regions (more on that later in this section).

Is There a Case for Colonialism?

Short answer: NO.

Although there have been some academic attempts to make a case for colonialism, using outlier cases such as Singapore, or bringing forward arguments on how colonizers brought education and other institutions to the countries colonized.

However, what these arguments miss is the terrible damage colonization brought to the peoples colonized and how enduring these effects have been. Colonial practices were brutal, and colonizers had many times little regard for human rights and sovereignty. “Modernization” practices had elements of separation of groups that were more similar to the Western phenotype and promoted segregation, conflict, and forced assimilation.

Exploring missionary activity may provide some guidance to examine the effects that ‘development’ programs conducted during the colonial period had. For the most part, this is because the provision of public goods was outsourced to missionaries, with colonial institutions focused on the investments on public goods that could allow them to access and extract the local resources (minerals or agricultural products).

Cagé and Rueda (2016) examine this issue and argue that missionary activity was heterogeneous across the African continent, and therefore, its effect is hard to calculate. Still, there are two areas where the effects are more clear. The first one is the introduction of the printing press, as it was used to print the Bible in the local languages to facilitate the introduction of Christianity, but it remained in certain regions for other uses. According to the authors, the presence of a printing press is correlated to higher media consumption and social capital. According to the authors, the mechanism behind this may be literacy and not necessarily the adoption of specific values.

The second area is health. Missionaries were the first ones to invest in ‘modern’ medicine in Africa, with 150 missionary doctors and more than 235 nurses working across the continent. This provision of health remained after independence. However, the introduction to Christianism also affected the local values and the sexual behavior adopted. The authors find that areas that are closer to areas closer to a historical mission settlement have a higher prevalence of HIV today. This may be related to the attitudes adopted towards the use of contraceptives, especially condoms.

5.4 Development policies after Independence

In many ways, the patterns of colonialism set the ground for the development of African politics after independence. During the colonial period, certain groups were supported over others, leading to the emergence of “Big Men”, leaders that became powerful as colonial governments gave them the task of controlling the population, in areas where the colonial settlers did not penetrate (Cheeseman and Fisher, 2019). As Acemoglu, Reed, and Robinson (2014) put it, “[these] chiefs were accountable to their occupiers, but the system did not require them to be accountable to their people.”

At the time of independence, these new leaders were in front of the opportunity to control vast territories. However, they were threatened by other Big Men that also wanted to gain control in a context with ethnic communities that did not believe themselves as being part of the same nation.

In response, these Big Men introduced a series of neo-patrimonial policies. Leaders used their power to break the rules, using their ethnic identity to distribute gifts (from jobs to assets) to maintain power. This led to a system in which coercion and co-optation worked in unison to maintain power, and fragile authoritarianism emerged (Cheeseman and Fisher, 2019).

In addition to this dimension, after independence, African countries faced another conundrum: how to promote economic growth? With deficient levels of literacy and poor infrastructure, governments had to create different ways to promote development. At the same time, they had to generate a sentiment of unity among the population in these artificial states.

Different patterns took place. In certain countries, such as South Africa, the government passed into the hands of European settler communities, and racial segregation was pursued. There was a shift towards pre-colonial traditions in other regions, such as ujamaa in Tanzania (extended family in Swahili). This involved the push for unifying policies, such as creating one-party states, with the idea that these would push people to the ‘same side’ while allowing competition at the local level and other types of -partial- competition in specific contexts. In certain countries, such as the DRC, competition was banned at any level, with the national leader, Mobutu Sese Seko, recentralizing power. But this was also the opportunity for governments to distance their countries from the colonial influence, leading to the creation of Pan-Africanism.

However, bear in mind that the independence process took place at the same time than the Cold War was developing, and African states participated as proxy areas for conflict, with both the East and the West wanting to gain influence in these areas. This had important consequences for the region’s political and economic configuration, as leaders were supported by the international community (East and West) irrespective of their domestic policies, as long as they joined one faction.

At the end of the Cold War, these leaders lost the unconditional support they had. As Fukuyama (1992) argued, ‘The End of History’ had arrived with the dominance of Western democracy8. This has not been the outcome, even if there has been a shift towards governance and institutions as tools for development in low- and middle-income countries. Still, as we will see later in this section, African countries have followed different political paths.

5.5 Structural Adjustment Period

At the end of the colonial period, African countries faced a series of issues. They had just ended a long period of ravaged extraction from Colonialist powers. The Colonial economies had been focused on the production and export of agricultural and mineral raw commodities, and little efforts had been put in promoting better health or education outcomes. Furthermore, during the colonial period there was little investment in infrastructure. These countries also inherited many repressive economic policies that were retained because they were an important source of government income.

Of course, talking about economic development paths and policies in Africa requires to look at much specific detail, as different countries followed different paths, However, the general trend is that, after Independence many African countries followed a series of economic policies to boost their economic growth. However, by the end of the 1970s, it became clear that these policies were not effective at promoting economic development and instead left the countries with very high levels of debt. Adverse terms of trade, chronic indebtedness, and a global recession in the 1980s, led to an increase in poverty, and a dire economic situation.

In the 1980s, multiple African countries approached international organizations such as the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) for relief debt. In return, these organizations asked for countries to adopt Structural Adjustment Programs (SAPs), which comprehended a series of ten macroeconomic conditions that were coined in 1989 as the ‘Washington Consensus’. These policies included:

- Small budget deficits

- Directed public expenditure (away from political motivations and toward neglected fields)

- Tax reform

- Financial liberalization

- Competitive exchange rate (liberalized)

- Trade liberalization

- Liberalization capital flows

- Privatization

- Reduction of regulations

- Secure property rights

Did the SAPs work?

In the 1990s and early 2000s, the evidence showed that countries that adopted these policies had worse outcomes (see, for instance, Shillington, 2019 or Easterly, 2000). However, a study by Archibong, B. et al. (2021) showed that, in the long run, countries that adopted these policies have experienced remarkable improvement in economic growth and a lower and more stable inflation. Still, it is hard to claim that these policies are behind these improvement (this is, that there is a causal relation), and that other factors are not behind this economic improvement. Furthermore, whereas these policies may have played a role in improving the macroeconomic context, they hurt different sectors of the population that were highly vulnerable, such as women and rural farmers. Finally, the main lesson after implementing these policies is that they need to adapt to the local context and have the support of the population.

5.6 Seminar Questions Module 2

5.6.0.1 Week 4:

- Pre-Colonial and Colonial African History

- How does history help us explain the development path of different countries? - How does pre-colonial and colonial history in Africa contribute to the development path followed by countries in the continent?

- Make sure you delve deeper into the effects of the trade of enslaved persons. the ‘Scramble of Africa’ and the resistent movements, as well as the colonial rule.

5.6.0.2 Week 5:

- Development policies after Independence

- How did the Washington Consensus policies affect the industrialization process of low- and middle-income countries? What political and social factors affected the development path of these countries in the second half of the Twentieth century?

5.7 Activities Module 2

You will watch a documentary on the colonial rule.

We will have our first debate: Does history determines the development path of a society?

We will evaluate the impact of the Washington Consensus policies on the development path of low- and middle-income countries.

- First Assessment

5.8 Readings Module 2

5.8.1 Required Readings Module 2

5.8.1.1 Week 4:

Pre-colonial Africa and trade of enslaved persons

Nunn, N. (2009), “The Importance of History for Economic Development”, Annual Economic Review, 1: 65-92

Nunn, N. (2008), “The Long-Term Effects of Africa’s Slave Trades”, Quarterly Journal of Economics, 123: 139-176.

Tuesday, January 31st- No in-session class. Instead, please watch: King Leopold’s Ghost: A Story of Greed, Terror and Heroism in Colonial Africa - Documentary film based on the book of the same name by Adam Hochschild (1988). The film contains scenes with high levels of violence for sensitive viewers If you are not willing to watch this documentary, please let me know and I will provide a suitable alternative for you. (You can watch it on Amazon, YouTube, Google Play or Apple TV)

Crash Course on Black American History Episode 1 and Episode 2.

Colonization and development

Michalopoulos, S. and Papaioannou, E. (2016), “The Long-Run Effects of the Scramble for Africa”, American Economic Review, Vol. 106(7). pp. 1802-1848.

Moss, T. and Resnick, D. (2018). African Development, 3rd. Ed. Boulder: Kynne Rienner- Chapter 2

5.8.1.2 Week 5:

After Independence

- Moss, T. and Resnick, D. (2018). African Development, 3rd. Ed. Boulder: Kynne Rienner- Chapter 3

Structural Adjustment

Spence, M. (2021). Some Thoughts on the Washington Consensus and Subsequent Global Development Experience Journal of Economic Perspectives, Vol. 35(3). pp. 67-82.

Archibong, B. et al. (2021). Washington Consensus Reforms and Lessons for Economic Performance in Sub-Saharan Africa , Vol. 35(3). pp. 133-156.

5.8.2 Additional Readings and Resources Module 2

Pre-Colonial Africa and Trade of Enslaved Persons

- A less-than-five-minute reading: Williams, D.L. “Was slavery a ‘necessary evil’? Here’s what John Stuart Mill would say” The Washington Post (July 30, 2020)

- Highly recommended: Watch the series High on the Hog on Netflix. Episode 1 is highly recommended. There is a book by Jessica Harris as well.

- Ehret, Ch. (2014) . “Africa in World History before ca. 1440”, In Emmanuel Akyeampong, Robert H. Bates, Nathan Nunn, James A. Robinson (eds) Africa’s Development in Historical Perspective, pp. 33-55. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Colonization and Development

- Nunn, N. and Qian, N. (2010). The Columbian Exchange: A History of Disease, Food, and Ideas. Journal of Economic Perspectives, Vol. 24(2), pp. 163-188

After Independence

- Discourse of former president of Tanzania, Julious Nyerere, at the University of Zambia in 1966: The Dilemma of the Pan-Africanist

Structural Adjustment

- Goldfajn, I. et al. (2021). Washington Consensus in Latin America: From Raw Model to Straw Man, Journal of Economic Perspectives, Vol. 35(3). pp. 109–132.

Additional Sources

- Anta Diop, Ch. (1987). Precolonial Black Africa. Chicago: Chicago Review Press.

- Cheeseman, N. and Fisher, J. (2019). Authoritarian Africa. New York: Oxford University Press

- Dalton, John T. and Tin Cheuk Leung (2014), “Why is Polygyny More Prevalent in Western Africa? An African Slave Trade Perspective”, Economic Development and Cultural Change, 63 pp. 599-632.

- Fenske, James and Namrata Kala (2015), “Climate and the Slave Trade”, Journal of Development Economics, 112: 19-32.

- Fenske, James and Namrata Kala (2016), 1807: Economic Shocks, Conflict and the Slave Trade, Working paper.

- Lipset, S. (1959), “Some Social Requisites of Democracy: Economic Development and Political Legitimacy”, The American Political Science Review, Vol. 53(1), pp. 69-105

- Przeworski, A. Alvarez, M., Cheibub, J-A. and Limongi, F. (2000). Democracy and development. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Whatley, Warren and Rob Gillezeau (2011), “The Impact of the Transatlantic Slave Trade on Ethnic Stratification in Africa”, American Economic Review Papers and Proceedings, Vol.101: pp. 571-576.

- Whatley, Warren C. (2014), “The Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade and the Origins of Political Authority in West Africa”, In Emmanuel Akyeampong, Robert H. Bates, Nathan Nunn, James A. Robinson (eds) Africa’s Development in Historical Perspective, pp. 460-488. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Zhang, Yu and Shahriar Kibriya (2016), The Impact of the Slave Trade on Current Civil Conflict in Sub-Saharan Africa, Working paper, Texas A&M University.

Terms and Definitions

Big-man politics: It is a political system where the politicians (Big men) keep power throughout the distribution of resources to certain sectors of the population. In return, politicians can rely on these persons to mobilize support for them (Cheeseman and Fisher, 2019).

Neo-patrimonialism: System in which the patrons use state resources to secure the support of sectors of the population, based on a hierarchical/‘traditional’ way. This system works in an informal way within a formal structure.

Strong state: “Form of organized domination that delivers order and public goods” (Centeno, )

State capacity: “Organizational and bureaucratic ability to implement governing projects” (Centeno,). “The ability of states to plan and execute policies and to enforce laws cleanly and transparently” (Fukuyama, 2004). Preferred definition –> “The capacity of the state to actually penetrate civil society and to implement logistically political decisions throughout the realm.” (Mann, 1984)

Power (in the context of state capacity): “Ability to get others to do things that they might not have done otherwise.” (Centeno, ; Dahl, 1957).